Summary

Immunofluorescence studies have revealed that H2AX is phosphorylated at the sites of DNA double-strand breaks induced by ionizing radiation and is required for recruitment of repair factors into nuclear foci after DNA damage. Therefore the function of H2AX is believed to be associated primarily with repair of DNA damage. Here we report a function of H2AX in cellular apoptosis. Our data showed that H2AX is phosphorylated by UVA-activated JNK. We also provided evidence showing that UVA induces caspase-3 and caspase-activated DNAse (CAD) activity in both H2AX wildtype and H2AX knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). However, DNA fragmentation occurred only in H2AX wildtype MEFs. Furthermore, H2AX phosphorylation was critical for DNA degradation triggered by CAD in vitro. Taken together, these data indicated that H2AX phosphorylation is required for DNA ladder formation, but not for the activation of caspase-3; and the JNK/H2AX pathway cooperates with the caspase-3/CAD pathway resulting in cellular apoptosis.

Introduction

The nucleosome is the fundamental unit of chromatin in eukaryotes, consisting of DNA wrapped around an octamer of two pairs each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. Linker histone H1 compresses linear nucleosome arrays into a 30 nm chromatin fiber (Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2004). The histone globular domains comprise the nucleosome core, from which the histone tails protrude, providing potential sites for histone modifications such as phosphorylation and acetylation (Bode and Dong, 2005; Taneja et al., 2004). Functional isoforms of histones are scattered throughout the mammalian genome. Reports have indicated that some of the histone variants have specialized biological functions such as DNA repair (Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2004; Rogakou et al., 1998).

H2AX is a variant of the histone H2A family, comprised of three distinct subfamilies, H2A1-H2A2, H2AZ and H2AX (Rogakou et al., 2000). The sequence differentiating H2AX from the other H2A subfamilies is located in the C-terminal motif (KATQAS*QEY-COOH) (Cheung et al., 2000; Taneja et al., 2004). Ser139 in this motif is the site of γ-phosphorylation. Ionizing radiation (IR) induces a rapid phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser139 that is mediated by an unknown signaling pathway (Rogakou et al., 2000; Rogakou et al., 1998). Phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) forms nuclear foci at the sites of IR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) and might play an important role in recruiting repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage (Celeste et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2000; Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2002; Paull et al., 2000). But the migration of repair and signaling proteins to DSBs is not affected in H2AX deficient or H2AX−/− cells, nor is H2AX phosphorylation needed for the initial recognition of DNA breaks (Celeste et al., 2003). In addition, the enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-dependent γH2AX foci do not reflect the presence of DSBs (Casali and Zan, 2004). The fact that H2AX deficiency is not detrimental to life further indicates that γH2AX foci formation does not necessarily reflect the presence of DSBs. Furthermore, the in vitro DNA end-joining reaction for the repair of DSBs was reported to occur independently of H2AX phosphorylation (Siino et al., 2002). Thus, the function of γH2AX remains elusive.

Members of the phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase family, including ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein (ATM), AT and Rad3-related protein (ATR) and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), were reported to be involved in the responses of mammalian cells to DSBs (Burma et al., 2001; Park et al., 2003; Stiff et al., 2004; Ward and Chen, 2001; Ward et al., 2004). A fraction of nuclear ATM has been shown to co-localize with γH2AX at the sites of DSBs in response to DNA damage. Further evidence suggested that ATM is required for H2AX phosphorylation induced by low doses of IR (Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2002). In addition, H2AX phosphorylation was reported to be regulated by ATR in response to DNA replication stress (Ward and Chen, 2001; Ward et al., 2004). However, no published data have shown that ATM, ATR or DNA-PK phosphorylates H2AX directly in vivo and conflicting conclusions have been drawn as to the involvement of these kinases in H2AX phosphorylation. For example, H2AX phosphorylation was detected in individual kinase dead mutants (ATM−/−, DNA-PK−/−, ATR−/−) (Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2004) and ATM did not contribute to IR-induced phosphorylation of H2AX in primary fibroblasts (Stiff et al., 2004). Furthermore, several cell lines deficient in DNA-PK did not exhibit a deficit in γH2AX formation after exposure to IR (Rogakou et al., 1998). Thus, some other as yet unknown kinases possibly phosphorylate H2AX.

Here we report that ultraviolet (UV) A irradiation strongly induced H2AX phosphorylation that was mediated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and phosphorylation of H2AX by JNK was associated with induction of apoptosis. These data are the first to show that H2AX phosphorylation by JNK is required for apoptosis occurring through the caspase-3/caspase-activated DNAse (CAD) pathway.

Results and Discussion

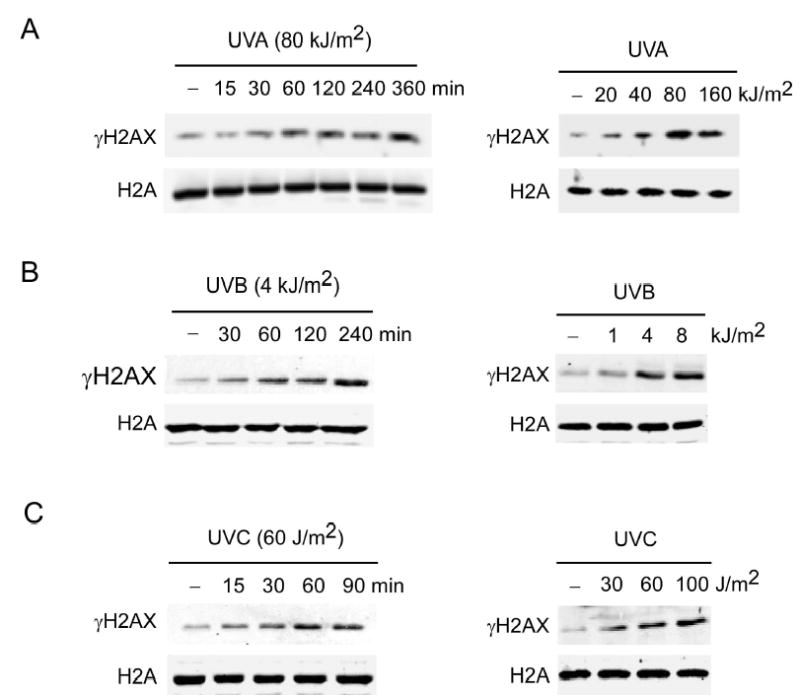

UV Induces Phosphorylation of H2AX

UV is an important etiological factor in human skin cancer and we used mouse skin epidermal JB6 cells to study the phosphorylation of H2AX. We found that UVA (320–400 nm), UVB (290–320 nm) or UVC (200–290 nm) induced strong phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX) in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A–C). Phosphorylation of H2AX is one of the first cellular responses when DSBs are induced by IR (Kobayashi et al., 2002; Woo et al., 2002). But some types of damage, and in particular that induced by UV exposure, do not elicit DSBs (Paull et al., 2000). Thus, the significance and mechanism of H2AX phosphorylation resulting from IR-induced DSBs appears to be distinct from UV-induced H2AX phosphorylation. UV-induced phosphorylation of H2AX might be involved in other as yet unidentified cellular functions. Because UVA is a main component of solar UV reaching the earth’s surface and a major contributor to skin cancer (Zhang et al., 2002), we used UVA to treat cells in the remaining experiments.

Figure 1.

UVA, UVB or UVC induces phosphorylation of H2AX

(A) JB6 cells were exposed to (A) UVA, (B) UVB, or (C) UVC and histones were extracted as described in “Experimental Procedures” after the incubation time indicated (left panels) or after 60 min following indicated doses of UVA (right panels). Cells not exposed to UV served as negative controls (−). For all experiments, histones were resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE followed by western analysis with antibodies against γH2AX or total H2A.

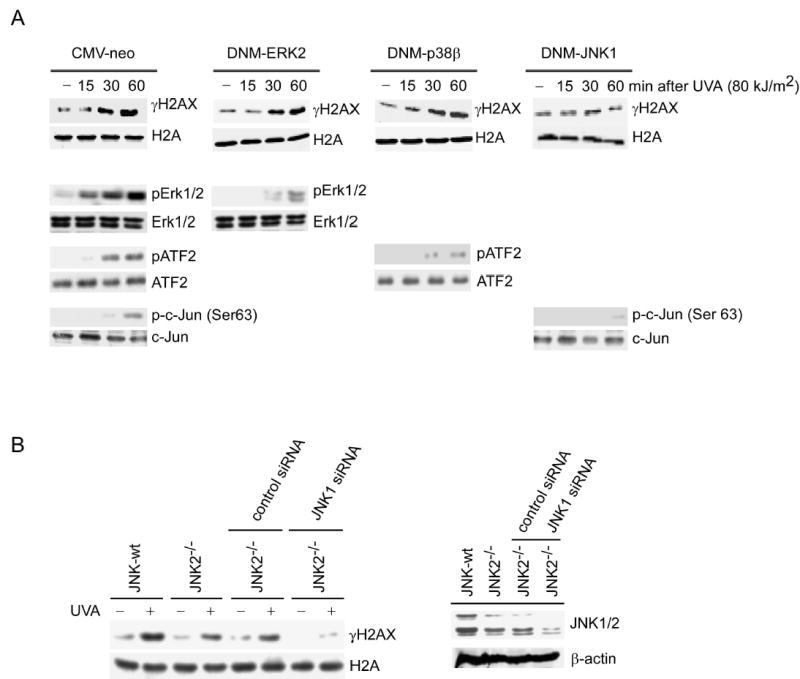

JNK Phosphorylates H2AX

The mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are a family of proteins that mediate distinct signaling cascades that are targets for diverse extracellular stimuli, including UV. These pathways are important in the regulation of a multitude of cellular functions including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, development, growth, and inflammation (Bode and Dong, 2003; Cheung et al., 2000; Dent et al., 2003). ERKs-activated RSK2 has been shown to be directly involved in histone H3 phosphorylation in vivo (Cheung et al., 2000; Sassone-Corsi et al., 1999). We used MAPK chemical inhibitors and dominant negative mutants (DNM) to investigate whether MAPKs are involved in the regulation of H2AX phosphorylation induced by UVA. Our data showed that the MEK inhibitor, PD98059, and the p38 inhibitor, SB202190, did not affect H2AX phosphorylation although each inhibited phosphorylation of their respective target proteins, ERKs and ATF2 (Figure S1). On the other hand, SP600125, a JNK inhibitor, strongly suppressed H2AX phosphorylation and its normal target, c-Jun (Figure S1). Some reports (Bain et al., 2003; Davies et al., 2000) indicated that SP600125 is a non-specific inhibitor in vitro and affects other kinases such as p70 S6K. However, our data showed that SP600125 had no effect on UVA-induced phosphorylation of p70 S6K (Thr421/424) (Figure S1, bottom right), suggesting that the inhibitory effect of SP600125 in vitro may be different from its effect in vivo. To address the non-specificity of chemical inhibitors, we used various DNM-MAPK cell lines, including DNM-JNK1 stably transfected cells, to determine whether JNK was involved in H2AX phosphorylation. Results indicated that DNM-JNK1 also strongly inhibited UVA-induced phosphorylation of H2AX (Figure 2A), which was consistent with the inhibition by SP600125. In contrast, DNM-ERK2 or DNM-p38β had little effect on H2AX phosphorylation. The DNM-MAPKs cell lines were each confirmed to suppress their respective targeted kinase activity following UVA exposure (Figure 2A, bottom panels). To further support a role for JNK in H2AX phosphorylation, we transfected siRNA JNK1 into JNK2 knock out cells (JNK2−/−) to create a double knockout of JNK. Results indicated that siRNA JNK1 effectively suppressed the level of JNK1 in JNK2−/− cells (Figure 2B, right panels) and siRNA JNK1 dramatically decreased UVA-induced phosphorylation of H2AX (Figure 2B, left panels). Overall these data strongly indicated that JNK is involved in UVA-induced phosphorylation of H2AX.

Figure 2.

DNM-JNK1 or JNK1 siRNA inhibits UVA-induced phosphorylation of H2AX

(A) JB6 stable transfectants (CMV-neo, DNM-ERK2, DNM-p38β or DNM-JNK1) were exposed to UVA and histones extracted at the indicated time after UV. Cells not exposed to UVA served as negative controls (−). Bottom panels represent control experiments to verify that each dominant negative mutant specifically inhibited its respective targeted kinase activity. (B) JNK2−/− MEFs transfected with mock siRNA or siRNA JNK1were treated with UVA (80 kJ/m2). H2AX phosphorylation at Ser139 (γH2AX) and histone H2A total protein level were determined. Right panel shows the effectiveness of siRNA JNK1 to suppress JNK level.

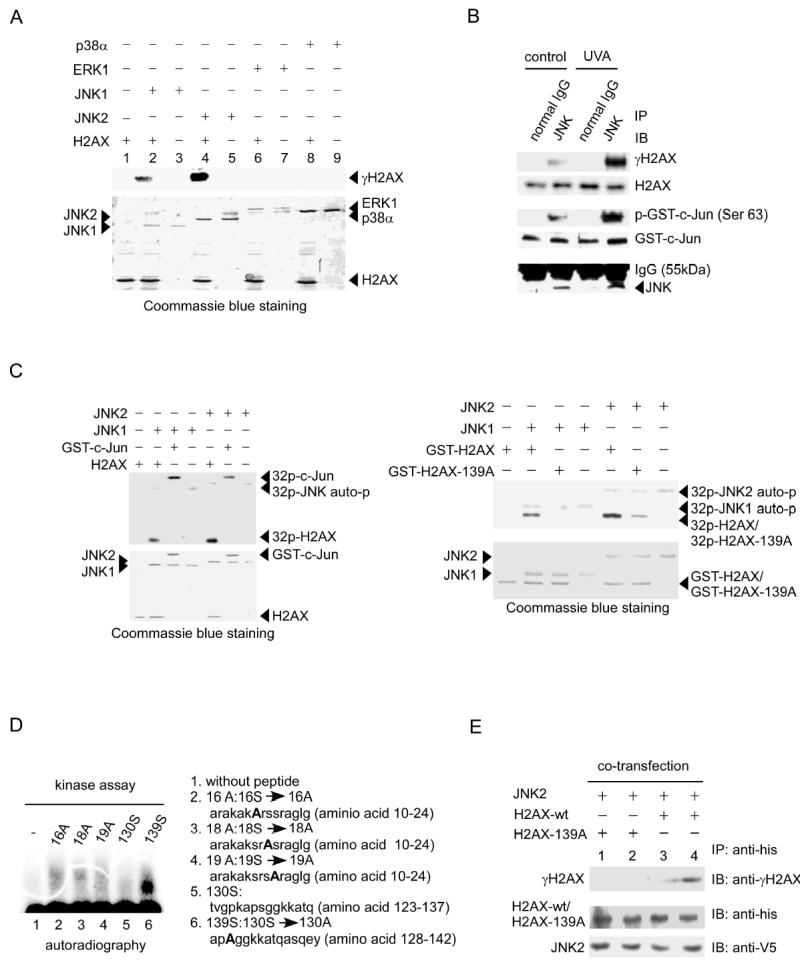

Next we used in vitro kinase assays to determine whether JNK phosphorylated Ser139 of H2AX directly. The results showed that commercially active JNK1 or JNK2 phosphorylated H2AX at Ser139 (Figure 3A, lanes 2, 4), whereas active ERK1 or p38α had no effect (Figure 3A, lanes 6, 8). UV is known to strongly and rapidly induce JNK phosphorylation and activation in some cell lines, including JB6 cells (Sabapathy et al., 2004; Tournier et al., 2000; Zhong et al., 2001). Endogenous JNK was immunoprecipitated from UVA-treated or untreated JB6 cells for in vitro kinase assays. Activated JNK is very low in cells not treated with UV and thus JNK-induced phosphorylation of H2AX or c-Jun was relatively weak (Figure 3B). On the other hand, UVA-activated JNK strongly and specifically phosphorylated H2AX (Ser139) (Figure 3B). The immunoprecipitated endogenous JNK phosphorylated Ser63 of c-Jun in vitro (Figure 3B) verifying that JNK was fully functional. We then used equal molar amounts of c-Jun or H2AX in the JNK kinase assay to compare the phosphorylation of these two substrates and found that the incorporation of γ-32P into c-Jun was similar to H2AX (Figure 3C, left panels). To further verify that H2AX was phosphorylated by JNK, Ser139 in H2AX was mutated to Ala (139A) to block its phosphorylation. We found that the H2AX mutant (H2AX-139A) dramatically decreased phosphorylation by JNK in vitro, indicating that Ser139 can be modified by JNK (Figure 3C, right panels). Then we designed five peptides (16A, 18A, 19A, 130S, 139S; Figure 3D, right) for in vitro kinase assays in order to perform a detailed analysis of other possible sites that could be phosphorylated by JNK. The peptide mapping analysis data showed that JNK1 induced strong phosphorylation of Ser139 (Figure 3D, left). Taken together, these data indicated that Ser139 is the major H2AX site that is directly phosphorylated by JNK. To further confirm that JNK phosphorylates H2AX at Ser139 in vivo, we co-transfected HEK 293 cells with JNK2 and H2AX-wt or H2AX-139A and then either treated (Figure 3E, lanes 2, 4) or did not treat (Figure 3E, lanes 1, 3) cells with UVA. The his-tagged overexpressed H2AX or H2AX-139A was immunoprecipitated for detection of Ser139 phosphorylation. Data indicated that UVA-activated JNK2 increased the phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser139 in vivo (Figure 3E, lane 4) but had no effect on the mutant H2AX (Figure 3E, lane 2).

Figure 3.

H2AX is phosphorylated by JNK

(A) The H2AX protein was used as a substrate for active protein kinases including p38α, ERK1, JNK1 and JNK2. Reactive products were subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blot to detect H2AX phosphorylation (γH2AX). Coommassie blue staining shows the level of H2AX and kinases in each reaction.

(B) H2AX and a GST-c-Jun fusion protein were used as substrates for JNK, which was immunoprecipitated from JB6 cells treated or not treated with UVA (80 kJ/m2). The normal IgG immune complex served as a negative control. The reactive products were subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blot analysis to detect γH2AX and H2AX (upper 2 panels). Phosphorylation of GST-c-Jun (Ser63) served as positive control (middle panel). Bottom panel shows the amount of JNK precipitated in each reaction.

(C) Equal molar amounts of H2AX or GST-c-Jun (left panels) or GST-H2AX or GST-H2AX-139A (right panels) were used as substrates for active JNK1 or JNK2. Reactive products were resolved by SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography or Coommassie blue staining.

(D) Five peptides were designed for in vitro kinase assays with active JNK1. Reaction samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography to detect phosphorylation (Lane 1, control without peptide).

(E) HEK 293 cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3.1/JNK2 and pcDNA4/H2AX or pcDNA4/H2AX-139A and 48 h later treated with UVA (80 kJ/m2). The expression level of JNK2 was detected with anti-V5. His-H2AX or his-H2AX-139A was immunoprecipitated with anti-his and the phosphorylation of the expressed H2AX or H2AX-139A was detected with an antibody against γH2AX.

IR leads to DSBs and induces phosphorylation of H2AX. Some groups reported that members of the PI 3-kinase family, ATM, ATR or DNA-PK regulated H2AX phosphorylation triggered by DSBs (Burma et al., 2001; Park et al., 2003; Paull et al., 2000; Stiff et al., 2004; Ward and Chen, 2001; Ward et al., 2004). In order to determine whether these kinases have a role in UVA-induced H2AX phosphorylation, we used 200 μM (Burma et al., 2001; Kurz et al., 2004; Paull et al., 2000) wortmannin, a PI 3-kinase family inhibitor, to treat cells before UVA exposure. We found that this concentration of wortmannin blocked ATM and ATR phosphorylation induced by UVA, but did not suppress phosphorylation of H2AX induced by UVA (Figure S3, upper panels). In addition, results showed H2AX phosphorylation occurred earlier than ATM phosphorylation (Figure S3, upper panels). We also treated ATM-wt or ATM−/− MEFs with UVA and found that UVA induced H2AX phosphorylation independently of ATM (Figure S3, bottom panels). These data suggested that UVA might induce H2AX phosphorylation independently of PI 3-kinase family members in JB6 cells. A similar conclusion was reached by other investigators who treated cells with doxorubicin (Kurz et al., 2004).

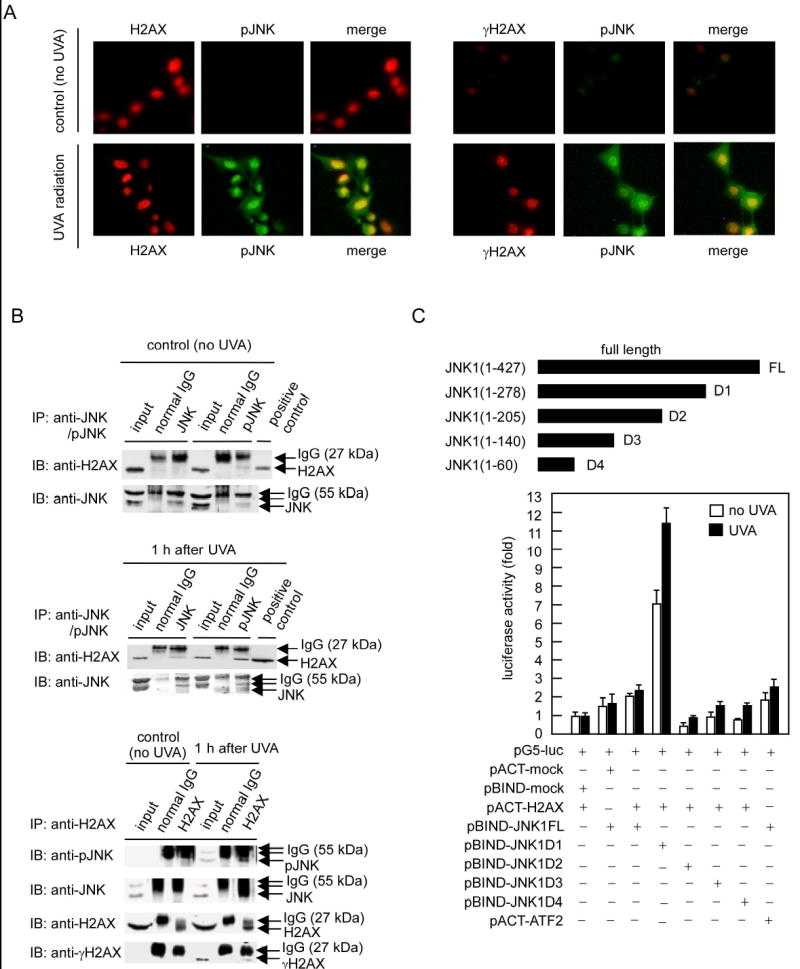

H2AX Co-Localizes and Interacts with UVA-Activated JNK In Vivo

We reasoned that phosphorylated JNK (pJNK) should bind or co-localize with H2AX or γH2AX in vivo if JNK phosphorylates H2AX. Immunofluorescence staining indicated that after UVA radiation, activated JNK (pJNK) translocated into the nucleus and co-localized with H2AX (Figure 4A, left panels) or γH2AX (Figure 4A, right panels). Specific complex formation between pJNK and H2AX was confirmed further by co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 4B, upper and middle panels) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (Figure 4B, lower panels). Together, these results suggested that UVA-activated JNK (pJNK) translocated into the nucleus to bind with H2AX, leading to H2AX phosphorylation. Next we used full-length (FL) and 4 deletion mutants (D1-D4) of JNK1 (Figure 4C) (Choi et al., 2005) in the mammalian two-hybrid assay to identify the domain in JNK that binds or regulates the binding with H2AX. Results indicated that if the C-terminal aa 206–427 (D2) of JNK1 were deleted, JNK1 did not bind to H2AX, suggesting that this domain is involved in the binding with H2AX. Furthermore, if the C-terminal aa 279–427 (D1) were deleted, the binding activity of JNK1 with H2AX increased dramatically, suggesting that this portion of JNK1 might regulate the binding of JNK1 and H2AX (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

H2AX co-localizes and interacts with JNK in vivo following UVA exposure

(A) JB6 cells were exposed to UVA (80 kJ/m2), fixed with paraformaldehyde, stained for pJNK (green), H2AX (red) or γH2AX (red) and observed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Localization of pJNK1 and total H2AX are indicated (left panels) with (bottom) or without (top) exposure to UVA and localization of pJNK1 and γH2AX are indicated (right panels) with (bottom) or without (top) exposure to UVA.

(B) The endogenous H2AX-pJNK complex was immunoprecipitated from UVA-treated or untreated cells with a JNK or pJNK antibody and H2AX was detected by immunoblotting with an H2AX antibody (top upper, middle panels). Two blots (UVA-treated or untreated cells) were probed with a JNK antibody to monitor the amount of JNK precipitated in each reaction (bottom upper, middle panels). Inputs are representative of whole cell lysates. The positive control (upper and middle panels) consists of histones extracted by acid as described in “Experimental Procedures”. The H2AX-immunoprecipitated chromatin proteins were probed with JNK, pJNK, H2AX and γH2AX antibodies (lower panels). Precipitation with normal IgG served as a negative control.

(C) The in vivo interaction of H2AX and JNK1 or JNK1 deletion mutants was assessed by mammalian two-hybrid assay. Luciferase activity indicates the fold-increase in relative luminescence units normalized to the negative control (value for cells transfected with only pGL-Luc and pACT-H2AX = 1.0). Data are represented as means ± S.D.

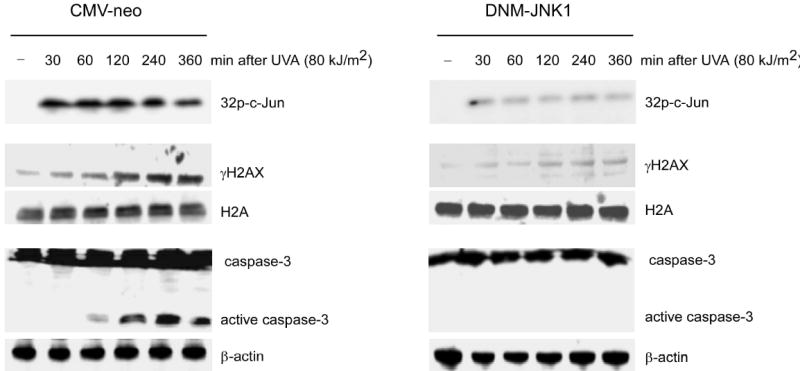

Phosphorylation of H2AX Might Be Related to Induction of Apoptosis

JB6 cells are sensitive to UVA, which can induce rapid apoptosis (Bode and Dong, 2003; Zhang et al., 2002) and JNK was reported to have a key role in UV-induced apoptosis (Banath and Olive, 2003; Sassone-Corsi et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001b). Furthermore, a recent report suggested that γH2AX is associated with cell death after cytotoxic treatments (Banath and Olive, 2003). Radiosensitive tumor cells exposed to IR retained γH2AX longer than IR-exposed radioresistant cells and tumors (Taneja et al., 2004). The long retention of γH2AX apparently made radiosensitive cells more sensitive to apoptosis. Based on these previous reports, we investigated whether the JNK/H2AX pathway is involved in mediating apoptosis by using a DNM-JNK1 stable transfectant. Results showed that JNK was activated within 30 min after UVA exposure and maintained a high activity until at least 360 min (Figure 5, top, left panel), whereas DNM-JNK1 strongly inhibited JNK activation (Figure 5, top, right panel). In addition, H2AX phosphorylation followed a similar time course (Figure 5, middle right, left panel) suggesting a parallel response. Because caspase-3 activation is a hallmark of apoptosis (Li et al., 2004; Tournier et al., 2000), we determined whether caspase-3 was activated at the same time. We observed that caspase-3 was cleaved or activated as early as 60 min after UVA exposure (Figure 5, bottom left). This activation occurred later than the H2AX phosphorylation (Huang et al., 2004). However, DNM-JNK1 not only suppressed UVA-induced activation of JNK but also blocked either UVA-induced H2AX phosphorylation (Figure 5, middle right) or caspase-3 activation (Figure 5, bottom right). We also found that the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, suppressed JNK-induced H2AX phosphorylation and caspase-3 activation, which was consistent with the inhibition by DNM-JNK1 (Figure S2). Taken together, these data indicated that JNK-mediated phosphorylation of H2AX might be related to apoptosis induced by UVA.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of H2AX and caspase-3 activation are suppressed by DNM-JNK1 JB6 stable transfectants (CMV-neo, DNM-JNK1) were exposed to UVA. One group of each stable cell line was used to extract histones at the indicated time following UV. Another group of each stable cell line was harvested at the indicated time following UV for detection of caspase-3 (full length and active fragments), β-actin and measurement of activation of JNK by in vitro kinase assay with c-Jun as substrate. Phosphorylated c-Jun was detected after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography (upper right, left panels). Cells not exposed to UVA served as negative controls (−).

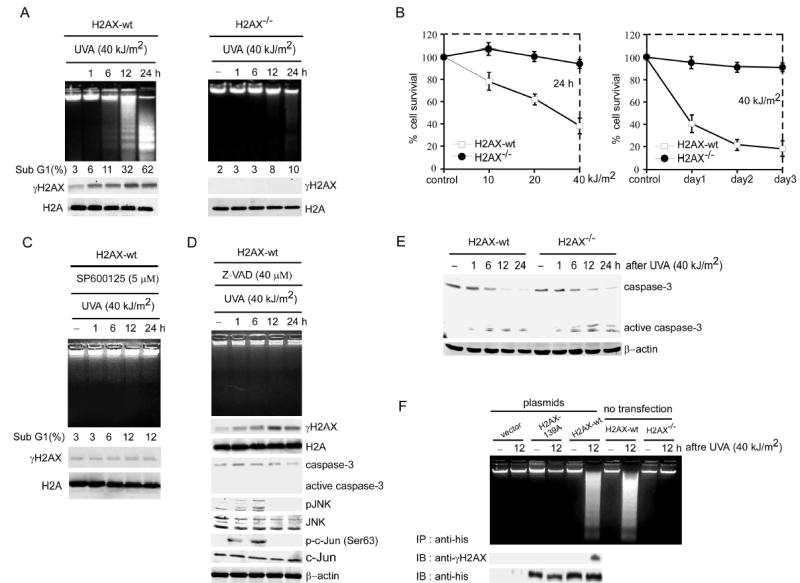

Phosphorylation of H2AX is required for DNA Fragmentation but not for Caspase-3 Activation

Next we examined apoptosis in H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEF to further confirm the potential role of H2AX phosphorylation. We observed that UVA induced apoptosis of H2AX-wt MEFs characterized by marked DNA fragmentation and a sub-G1 cell population that reached 32% at 12 h and 62% at 24 h after UVA exposure (Figure 6A, left panel). In contrast, H2AX−/− MEFs were markedly resistant to UVA-induced apoptosis (Figure 6A, right panel). The resistance was characterized by an inhibition of DNA fragmentation and a percentage of sub-G1 cells that reached only 10% in H2AX−/− MEFs 24 h after UVA exposure (Figure 6A, right panel). At the same time, H2AX-wt MEFs maintained a high level of γH2AX until 24 h after UVA exposure (Figure 6A, left panel), whereas no γH2AX was detected in H2AX−/− MEFs (Figure 6A, right panel). We also used etoposide to induce apoptosis and obtained similar results to those described for UVA (data not shown). Furthermore, we found that the survival of H2AX-wt cells was reduced substantially by UVA in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 6B, left and right panels, respectively). We then used the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, to treat H2AX-wt MEFs before UVA radiation. The results (Figure 6C) showed that SP600125 inhibited UVA-induced H2AX phosphorylation, DNA fragmentation and accumulation of cells in sub-G1 in H2AX-wt MEFs. Overall, these data provide strong evidence that H2AX phosphorylation by JNK is required for the induction of apoptosis.

Figure 6.

H2AX phosphorylation is required for cells to undergo apoptosis

(A) H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs were exposed to UVA and harvested at the indicated time after UVA. One group of each cell type was prepared for the DNA fragmentation ladder assay (upper panels) and another group of each type was divided into two parts. One part was prepared for determination of sub-G1 fraction by flow cytometry (middle panels) and the other was used to detect γH2AX or total H2A (lower panels).

(B) H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs were exposed to the indicated dose of UVA and cell survival was evaluated at 24 h after UVA (left panel) or at the indicated day (right panel) by MTS assay as described in “Experimental Procedures”. Cells not exposed to UVA served as control.

(C) H2AX-wt MEFs were treated with SP600125 (5 μM) 1 h before exposure to UVA and harvested at the indicated time after UVA. One group of cells was prepared for the DNA fragmentation ladder assay (upper panel). Another group of cells was divided into two parts. One part was prepared for determination of sub-G1 fraction by flow cytometry (middle panel) and the other part was used for detection of γH2AX and total H2A (lower panels).

(D) H2AX-wt MEFs were treated with the caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-VAD (40 μM), 1 h before exposure to UVA. Harvested cells were used for the DNA ladder assay (upper panel) or to detect γH2AX, caspase-3 (full length and active fragments), pJNK and JNK, p-c-Jun (Ser63) and c-Jun. Detection of total H2A and β-actin was used to confirm equal protein loading.

(E) As for (A), cells following UVA exposure were lysed at the indicated time to detect caspase-3 (full length and active fragments). β-actin was used to confirm equal protein loading. For all experiments, cells not exposed to UVA served as negative controls (−).

(F) H2AX−/− MEFs 48 h after transfection with pcDNA4 (vector), pcDNA4/H2AX-wt, or pcDNA4/H2AX-139A and H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs without transfection were treated with UVA. Harvested cells were used for the DNA ladder assay (upper panel) and western analysis to detect γH2AX and H2AX or H2AX-139A from the anti-his-immunoprecipitated complex.

A recent report indicated that UV induces apoptosis through the JNK/cytochrome c/caspase-3 pathway (Tournier et al., 2000). We treated H2AX-wt cells with the caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-VAD, before UVA exposure, and found that Z-VAD strongly inhibited caspase-3 activation and DNA fragmentation, but did not affect H2AX, JNK or c-Jun phosphorylation (Figure 6D). Thus, UVA-induced JNK and H2AX phosphorylation did not occur in response to the activation of caspase-3, suggesting that both H2AX phosphorylation and caspase-3 activation might be required for DNA fragmentation. This was further confirmed by experiments in which UVA induced caspase-3 activation in both H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs (Figure 6E). Overall, results indicated that neither UVA-induced H2AX phosphorylation nor caspase-3 activation alone is sufficient to induce apoptosis in this model system. These data suggested that H2AX cooperates with caspase-3 to determine the final cellular fate. To investigate the importance of H2AX phosphorylation at Ser139 in apoptosis, we mutated Ser139 in H2AX to Ala (139A) to block the phosphorylation. Then we transfected H2AX-139A or H2AX-wt into H2AX−/− MEFs. As expected, our data showed that H2AX-wt but not H2AX-139A restored the ability to induce apoptosis in H2AX−/− MEFs with UVA treatment (Figure 6F).

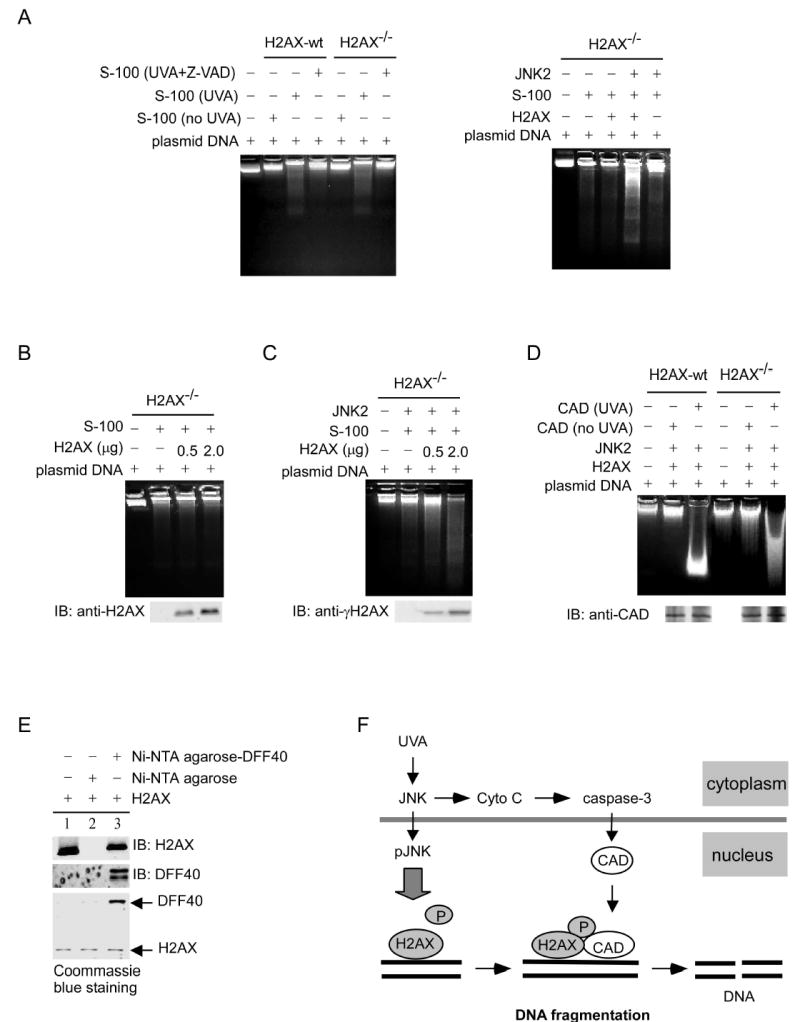

Phosphorylation of H2AX by JNK Regulates DNA Fragmentation Mediated by Caspase-3/CAD

We used a cell-free system to further investigate the role of H2AX phosphorylation in DNA fragmentation. The cytosolic (S-100) fractions, isolated from H2AX-wt or H2AX−/− MEFs either treated with UVA or with Z-VAD before UVA radiation, were used to cleave naked DNA. We found that the S-100 fractions isolated from UVA-induced H2AX-wt or H2AX−/− MEFs cleaved naked DNA weakly and that this DNA degradation was suppressed by inhibition of caspase-3 (Figure 7A, left panel). This suggested that nuclear proteins (e.g., H2AX) may be needed to work together with the S-100 fractions to fully cleave DNA (Liu et al., 1998). We next investigated whether H2AX regulated DNA degradation in vitro. This was accomplished by incubating S-100 fractions, isolated from UVA-treated H2AX−/− cells, with exogenous H2AX that had been phosphorylated by active JNK. Our data showed that phosphorylated H2AX increased DNA degradation (Figure 7A, right panel). This was further confirmed by experiments in which S-100 fractions isolated from UVA-treated H2AX−/− cells were incubated with increasing amounts of nonphosphorylated H2AX (Figure 7B) or H2AX to be phosphorylated by JNK (γH2AX) (Figure 7C). Results clearly indicated that H2AX phosphorylation was required for DNA degradation in vitro. The caspase-3 down stream target, CAD, has been reported to be an important endonuclease associated with DNA fragmentation (Widlak et al., 2001). Therefore, we used immunoprecipitated-CAD from H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs treated or not treated with UVA to determine whether CAD activity was regulated by phosphorylated H2AX. The data indicated that CAD from UVA-treated cells cleaved DNA very strongly when H2AX was phosphorylated (Figure 7D). These data were also consistent with Figure 6E, suggesting that the caspase-3/CAD pathway was activated in both H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs induced by UVA. In cells not treated with UVA, the inhibitor of CAD (ICAD) was not cleaved by caspase-3, which appeared to be in a CAD/ICAD complex that had no activity and could not cleave DNA (Liu et al., 1998) (Liu et al., 1998) (Figure 7D). Taken together, the data (Figure 7A-D) suggested that H2AX phosphorylation regulates DNA degradation induced by CAD.

Figure 7.

H2AX phosphorylation results in enhanced DNA cleavage by CAD

(A) H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs were exposed to UVA (40 kJ/m2) or treated with a caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-VAD, 1 h before UVA exposure. Then the cytosolic or S-100 fractions were extracted and incubated with naked DNA (plasmid pcDNA3) as described in “Experimental Procedures.” The reaction samples were separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis (left panel). The S-100 (80 μg) fractions isolated from UVA (40 kJ/m2)-treated H2AX−/− MEFs were incubated with DNA (8 μg) and H2AX protein (0.5 μg) that had or had not been preincubated at 30 °C for 30 min with an active JNK2 to promote H2AX phosphorylation. The reaction samples were separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis (right panel). (B) The S-100 (80 μg) fractions isolated from UVA (40 kJ/m2)-stimulated H2AX−/− MEFs were incubated with DNA (8 μg) and different doses of nonphosphorylated H2AX. Each reaction sample was divided into two parts. One part was separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis for DNA degradation analysis (upper panel) and another part was used to monitor H2AX protein level (lower panel).

(C) The S-100 fractions (80 μg) isolated from UVA (40 kJ/m2)-exposed H2AX−/− MEFs were incubated with DNA (8 μg) and different doses of H2AX, which had or had not been preincubated at 30 °C for 30 min with an active JNK2 to induce phosphorylation. The reaction samples were separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. The western blot (lower panel) indicates the level of γH2AX.

(D) H2AX was phosphorylated first by JNK2 and then mixed with DNA (8 μg) and CAD immunoprecipitated from H2AX-wt or H2AX−/− MEFs exposed or not exposed to UVA. The reaction samples were separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis to visualize DNA degradation. The western blot indicates that CAD was precipitated from H2AX-wt or H2AX−/− MEFs (lower panel).

(E) H2AX was incubated with PBS (lane 1, input), Ni-NTA agarose (lane 2), or Ni-NTA agarose-DFF40 (lane 3) for protein binding. Then the binding was analyzed by western blot and Coommassie blue staining.

(F) A model of apoptosis regulated by cooperation between the JNK/H2AX pathway and caspase-3/CAD (DFF40) pathway is proposed. When cells are exposed to UVA, JNK is activated and translocated into the nucleus where it phosphorylates H2AX. At the same time, UV-activated JNK can also stimulate caspase-3 activation through the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. Phosphorylated nuclear H2AX regulates DNA fragmentation mediated by CAD (DFF40) during apoptosis.

If CAD activity is mediated by phosphorylated H2AX, H2AX could act by binding to CAD. Therefore we used an in vitro binding assay to confirm this hypothesis. DNA fragmentation factor-40 (DFF40) is the human homologue of mouse CAD. We made recombinant DFF40 and purified it using Ni-NTA agarose for the protein binding assay. H2AX was added to Ni-NTA agarose-DFF40 beads or to Ni-NTA agarose only and results showed that DFF40 bound to H2AX in vitro (Figure 7E).

At present, most research regarding the regulation or induction of apoptosis has focused on upstream cytoplasmic pathways. But the underlying molecular mechanisms that govern the nuclear events (e.g., condensation and DNA fragmentation) remain unclear (Cheung et al., 2003). Based on data presented in this report, we propose a model of apoptosis regulated by the cooperation or cross talk between the JNK/H2AX and caspase-3/CAD (DFF40) pathways (Figure 7F). When cells are exposed to UVA, JNK is activated and subsequently translocates into the nucleus and phosphorylates H2AX. At the same time, activated JNK also stimulates caspase-3 through the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria (Tournier et al., 2000). The phosphorylated H2AX in the nucleus regulates DNA fragmentation mediated by the caspase-3 down-stream target, CAD (DFF40), during apoptosis. Without H2AX phosphorylation, caspase-3/CAD (DFF40) cannot induce DNA fragmentation. Furthermore, histone H2B phosphorylation was recently reported to be important for apoptotic chromatin condensation (Cheung et al., 2003). Thus, modified histones may serve as signaling platforms to control nuclear apoptotic events. H2AX was also reported to function as a tumor suppressor in mice (Bassing et al., 2003). H2AX-deficiency dramatically accelerates the onset of lymphomas and other cancers on a p53-deficient background and the lack of H2AX might inhibit apoptosis in tumor cells. Thus, the function of γH2AX seems not to be limited to DNA damage repair but might also be involved in the regulation of apoptosis and prevention of tumorigenesis.

Experimental Procedures

Stable Transfectants and Cell Culture

The CMV-neo vector plasmids were constructed as reported (Huang et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2001a). Mouse epidermal JB6 promotion-sensitive Cl41 and stable transfectants, CMV-neo mass (Cl41), dominant negative mutant (DNM) JNK1 (DNM-JNK1), p38 (DNM-p38β) and ERK2 (DNM-ERK2) were established as described (Zhang et al., 2001a). Cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 25 μg/ml gentamicin in a 37° C 5% CO2 incubator. Before each experiment, transfectants were selected with G418 and verified with their respective antibodies. JNK-wt and JNK2−/− MEFs, ATM-wt and ATM−/− MEFs, immortalized H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs (passage 16-21, derived from C57/Bl6 mice) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented as above.

Treatment of Cells with UV

Cells were seeded in 10- or 15-cm dishes and cultured as above until 80% confluence. JB6 cells were treated for 1 h prior to UV with kinase inhibitors PD98059, SB202190, SP600125 or wortmannin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs were treated with Z-VAD or SP 600125 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) 1 h before UV. To create JNK1/2 deficient cells, JNK1 siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was transfected into JNK2−/− cells to knock down JNK1 expression; JNK2−/− cells transfected with control siRNA served as controls. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for description of UV sources.

Total Cellular Protein or Histone Extraction and Western Analysis

Cellular proteins were extracted after UV exposure by disrupting cells in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCI, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF). For histone extraction after UV exposure, cells were lysed in NETN buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris, pH 8, 0.5% NP-40) and centrifuged 5 min. Histones were extracted from the pellets with 0.1 M HCl (Ward and Chen, 2001). The protein samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked at room temperature for 1 h with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST). Primary antibodies to detect phosphorylated H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX), H2A, H2AX (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY MA), caspase-3, phosphorylated JNK, total JNK, phosphorylated ERK1/2, total ERK1/2, phosphorylated p70 S6K (Thr421/424), total p70 S6K, phosphorylated ATF2 (Thr69/71), total ATF2, phosphorylated c-Jun (Ser63), total c-Jun, phosphorylated ATM (Ser1981), total ATM, phosphorylated ATR (Ser428), total ATR, β-actin (Cell Signaling Biotechnology, Inc., Beverly, MA) were incubated with membranes at 4 °C overnight. Membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody in 5% nonfat milk/TBST for 3h at 4 °C. Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Amersham, Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

Construction of Expression Vectors

Ser139 in H2AX was mutated to Ala (139A) to study phosphorylation (QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Stratagene, La Lolla, CA). Mutated H2AX or H2AX-wt was inserted into pcDNA4 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for transfection in HEK293 cells and H2AX−/− MEFs and pGEX-5X-1 vectors (Amersham Biosciences Corp) to generate GST-H2AX-wt and GST-H2AX-139A fusion proteins. H2AX was also introduced into the Bam HI/Xba I site of the pACT vector to generate pBIND-H2AX for the mammalian two-hybrid assay.

Immunoprecipitation and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

For immunoprecipitation, JB6 cells were treated or not treated with UVA (80 kJ/m2) and then disrupted in lysis buffer as above but including 25 U/ml of benzonase (Novagen). Cell lysates were incubated with a JNK or pJNK antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) at 4 °C overnight and protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for an additional 4 h. Duplicate blots were made from the same set of experiments. One blot was probed with an H2AX antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) to detect H2AX in the JNK-H2AX immunocomplex and the other blot was probed with a JNK antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.). Proteins were revealed using ECL reagents (Amersham Biosciences Corp.). To investigate whether H2AX is phosphorylated, pcDNA3.1/JNK2 and pcDNA4/H2AX or pcDNA4/H2AX-139A plasmids were transfected into HEK 293 cells or H2AX−/− MEFs. After UVA, these cells were disrupted as above. H2AX or H2AX-139A was precipitated by anti-his (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser139 (γH2AX) was detected. The cell lysate was also used to detect the expression of JNK2 with anti-V5 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments, JB6 cells were exposed to UVA (80 kJ/m2) and then processed according to the instructions from the manufacturer (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.; see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Immunoprecipitated histones and histone-bound protein complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with JNK, pJNK, H2AX, or γH2AX antibodies.

Immunofluorescence Staining

To study co-localization of endogenous pJNK and H2AX or pJNK and γH2AX in vivo, two groups of JB6 cells were fixed in 30 % paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 30 min after UVA (80 kJ/m2). For group 1, fixed cells were incubated with pJNK mouse monoclonal (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) and H2AX rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Biotechnology, Inc.), followed by incubation with green-fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 dye-labeled anti-mouse and red-fluorescent Alexa Fluor 568 dye-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), respectively. For group 2, the fixed cells were incubated with pJNK rabbit polyclonal and γH2AX mouse monoclonal antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), followed by incubation with green-fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 dye-labeled anti-rabbit and red-fluorescent Alexa Fluor 568 dye-labeled anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All samples were viewed with a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Bensheim, Germany).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

To detect H2AX phosphorylation, the H2AX protein (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) was mixed together with active ERK1, JNK1, JNK2 or p38α proteins (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), 0.2 mM ATP and 1x kinase buffer and incubated at 30 °C for 15 min. The reactive products were divided into two parts. One part was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE for western blot analysis and the other was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE for Coommassie blue staining. In addition, H2AX phosphorylation was also measured using immunoprecipitated JNK and a kinase assay according to the method recommended by the manufacturer (Cell Signaling Biotechnology, Inc.; see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). For the in vitro kinase assay to detect γ-32p incorporation, GST-c-Jun (Choi et al., 2005) and H2AX (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) proteins or GST-H2AX or GST-H2AX-139A proteins were mixed together with active JNK1 and JNK2 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), 1 μCi of [γ-32p] ATP and 1x kinase buffer and incubated at 30 °C for 15 min. The reactive products were separated by SDS-PAGE for autoradiography and Coommassie blue staining. To further investigate whether Ser139 in H2AX is targeted by JNK directly, we designed five peptides (16A, 18A, 19A, 130S and 139S) for peptide mapping analysis. 16A, 18A and 19A comprised 25 N-terminal residues (aa 10–24) in H2AX. In 16A, 18A or 19A, Ser16, Ser18 or Ser19, respectively, was mutated to Ala to block the respective phosphorylation. 130S contained amino acids 123–137 harboring Ser130 and 139S contained amino acids 128–142 in H2AX. In 139S, Ser130 was mutated to Ala to block possible phosphorylation of Ser130. Then the synthesized peptides (Invitrogen) were mixed with active JNK1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), 1 μCi of [γ-32p] ATP and 1x kinase buffer, incubated at 30 °C for 15 min and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Mammalian Two-Hybrid Assay

To identify the binding domain in vivo, we used the mammalian two-hybrid assay as described previously (Choi et al., 2005).

Determination of Sub-G1 by Flow Cytometry

Determination of sub-G1 fractions was determined according to published protocols (see http://www.cancer.ucsd.edu/Research/Shared/flow/Protocols). Briefly, after UVA exposure, cells were fixed and then stained with propidium iodide (PI). The DNA content was determined by flow cytometry and the sub-G1 portion was considered to be the apoptotic cell population.

Cell Survival Assays

To measure the sensitivity of cells to UVA, H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs were plated at 10,000 cells/well on 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h prior to UV. Following UVA, cell viability was determined in triplicate at various time points or UVA dose using the MTS assay according to the instructions from the manufacturer (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation assay kit, Promega, Madison, WI). The results were compiled using the Multiskan MS plate reader (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

DNA Fragmentation or In Vitro DNA Degradation Assay

H2AX-wt and H2AX −/− MEFs were treated with UVA (40 kJ/m2) and parallel groups of H2AX-wt cells were treated with SP600125 or Z-VAD for 1 h before UVA radiation. The cells were disrupted by adding DNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX) at various times and cells were centrifuged at 12,000xg for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant fraction containing fragmented DNA was mixed with 0.5 ml of isopropanol at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000xg for 10 min at 4 °C. The DNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol and resuspended in Tris-HCI (pH 8.0) with 100 μg/ml RNAse for 2 h. DNA fragments were separated by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light. To investigate whether H2AX expression in H2AX−/− MEFs restores UVA-induced apoptosis, pcDNA4/H2AX-wt or pcDNA4/H2AX-139A was individually transfected into H2AX−/− MEFs following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Lipofectamine Plus Reagents, Invitrogen). The transfected pcDNA4 empty vector was used as a control. Cells were treated with UVA (40 kJ/m2) 48 h after transfection and used for the DNA fragmentation test.

To investigate in vitro DNA degradation, we used a cell-free system. Six hours after UVA exposure (40 kJ/m2), H2AX-wt or H2AX−/− MEFs were harvested and the respective cytosolic fractions (S-100 fractions) were prepared as described previously (Liu et al., 1996). DNA cleavage was assayed by incubating the S-100 fractions (80 μg) and naked DNA (pcDNA3) (8 μg) (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 2 h in a final volume adjusted to 60 μl with buffer A (20 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM sodium EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 PMSF). To investigate whether H2AX phosphorylation affects DNA cleavage, H2AX (2 μg) was first phosphorylated by active JNK2 (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) at 30 °C for 30 min. Then the kinase reaction products were mixed with the S-100 fractions or CAD and pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The products were loaded onto a 1.8% agarose gel containing 5 μl ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light.

In Vitro Protein Binding Assay

The expression plasmid (pET-15b-DFF40His) was transformed into BL21 (DE3) Escherichia coli. The expression of DFF40 was induced by isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and the recombinant DFF40 protein was purified using Ni-NTA-agarose beads (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Then 2 μg of the H2AX protein (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) was incubated with Ni-NTA-agarose-DFF40 or Ni-NTA-agarose at 4°C for 2 h. The Ni-NTA-agarose-DFF40-H2AX complex sample was boiled and separated by SDS–PAGE for western blot with antibodies against total H2AX (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.) or DFF40 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and Coommassie blue staining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. André Nussenzweig (Experimental Immunology Branch, NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD) for providing the immortalized H2AX-wt and H2AX−/− MEFs; Dr. Yang Xu (Department of Biology, University of California, San Diego, CA) for ATM-wt and ATM−/− MEFs; Dr. Roger J. Davis (Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA) for the JNK2 plasmid; Dr. Xiaodong Wang (Department of Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) for the pET-15b-DFF40His; Dr. Joseph S. Siino (Division of Biological Science, University of California, Davis, CA) for the H2AX cDNA; Dr. Craig H. Bassing (CBR Institute for Biomedical Research, Boston, MA) for helpful suggestions pertaining to this work; and Todd Schuster (Hormel Institute, University of Minnesota) for help performing the cell apoptosis assays. This work is supported by the Hormel Foundation and NIH grants CA77646, CA81064, CA88961, CA27502 and CA11135.

References

- Bain J, McLauchlan H, Elliott M, Cohen P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem J. 2003;371:199–204. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banath JP, Olive PL. Expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX as a surrogate of cell killing by drugs that create DNA double-strand breaks. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4347–4350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassing CH, Suh H, Ferguson DO, Chua KF, Manis J, Eckersdorff M, Gleason M, Bronson R, Lee C, Alt FW. Histone H2AX: a dosage-dependent suppressor of oncogenic translocations and tumors. Cell. 2003;114:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode AM, Dong Z. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in UV-induced signal transduction. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.167.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode AM, Dong Z. Inducible covalent posttranslational modification of histone H3. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re4. doi: 10.1126/stke.2812005re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42462–42467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali P, Zan H. Class switching and Myc translocation: how does DNA break? Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1101–1103. doi: 10.1038/ni1104-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeste A, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Kruhlak MJ, Pilch DR, Staudt DW, Lee A, Bonner RF, Bonner WM, Nussenzweig A. Histone H2AX phosphorylation is dispensable for the initial recognition of DNA breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:675–679. doi: 10.1038/ncb1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HT, Bhandoola A, Difilippantonio MJ, Zhu J, Brown MJ, Tai X, Rogakou EP, Brotz TM, Bonner WM, Ried T, Nussenzweig A. Response to RAG-mediated VDJ cleavage by NBS1 and gamma-H2AX. Science. 2000;290:1962–1965. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P, Allis CD, Sassone-Corsi P. Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell. 2000;103:263–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WL, Ajiro K, Samejima K, Kloc M, Cheung P, Mizzen CA, Beeser A, Etkin LD, Chernoff J, Earnshaw WC, Allis CD. Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell. 2003;113:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BY, Choi HS, Ko K, Cho YY, Zhu F, Kang BS, Ermakova SP, Ma WY, Bode AM, Dong Z. The tumor suppressor p16(INK4a) prevents cell transformation through inhibition of c-Jun phosphorylation and AP-1 activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:699–707. doi: 10.1038/nsmb960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent P, Yacoub A, Fisher PB, Hagan MP, Grant S. MAPK pathways in radiation responses. Oncogene. 2003;22:5885–5896. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Celeste A, Ward I, Romanienko PJ, Morales JC, Naka K, Xia Z, Camerini-Otero RD, Motoyama N, et al. DNA damage-induced G2-M checkpoint activation by histone H2AX and 53BP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:993–997. doi: 10.1038/ncb884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, Lee A, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Ma WY, Dong Z. Requirement for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in epidermal growth factor-induced AP-1 transactivation and transformation in JB6 P+ cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6427–6435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, King MA, Halicka HD, Traganos F, Okafuji M, Darzynkiewicz Z. Histone H2AX phosphorylation induced by selective photolysis of BrdU-labeled DNA with UV light: relation to cell cycle phase. Cytometry A. 2004;62:1–7. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi J, Tauchi H, Sakamoto S, Nakamura A, Morishima K, Matsuura S, Kobayashi T, Tamai K, Tanimoto K, Komatsu K. NBS1 localizes to gamma-H2AX foci through interaction with the FHA/BRCT domain. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1846–1851. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz EU, Douglas P, Lees-Miller SP. Doxorubicin activates ATM-dependent phosphorylation of multiple downstream targets in part through the generation of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53272–53281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Nijhawan D, Wang X. Mitochondrial activation of apoptosis. Cell . 2004116:S57–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00031-5. 52 p following S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li P, Widlak P, Zou H, Luo X, Garrard WT, Wang X. The 40-kDa subunit of DNA fragmentation factor induces DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8461–8466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Chan DW, Park JH, Oettinger MA, Kwon J. DNA-PK is activated by nucleosomes and phosphorylates H2AX within the nucleosomes in an acetylation-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6819–6827. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paull TT, Rogakou EP, Yamazaki V, Kirchgessner CU, Gellert M, Bonner WM. A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage. Curr Biol. 2000;10:886–895. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Nieves-Neira W, Boon C, Pommier Y, Bonner WM. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9390–9395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabapathy K, Hochedlinger K, Nam SY, Bauer A, Karin M, Wagner EF. Distinct roles for JNK1 and JNK2 in regulating JNK activity and c-Jun-dependent cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:713–725. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassone-Corsi P, Mizzen CA, Cheung P, Crosio C, Monaco L, Jacquot S, Hanauer A, Allis CD. Requirement of Rsk-2 for epidermal growth factor-activated phosphorylation of histone H3. Science. 1999;285:886–891. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siino JS, Nazarov IB, Zalenskaya IA, Yau PM, Bradbury EM, Tomilin NV. End-joining of reconstituted histone H2AX-containing chromatin in vitro by soluble nuclear proteins from human cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;527:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiff T, O'Driscoll M, Rief N, Iwabuchi K, Lobrich M, Jeggo PA. ATM and DNA-PK function redundantly to phosphorylate H2AX after exposure to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2390–2396. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja N, Davis M, Choy JS, Beckett MA, Singh R, Kron SJ, Weichselbaum RR. Histone H2AX phosphorylation as a predictor of radiosensitivity and target for radiotherapy. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2273–2280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, Xu J, Turner TK, Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science. 2000;288:870–874. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IM, Chen J. Histone H2AX is phosphorylated in an ATR-dependent manner in response to replicational stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47759–47762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IM, Minn K, Chen J. UV-induced ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related (ATR) activation requires replication stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9677–9680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widlak P, Li LY, Wang X, Garrard WT. Action of recombinant human apoptotic endonuclease G on naked DNA and chromatin substrates: cooperation with exonuclease and DNase I. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48404–48409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo RA, Jack MT, Xu Y, Burma S, Chen DJ, Lee PW. DNA damage-induced apoptosis requires the DNA-dependent protein kinase, and is mediated by the latent population of p53. Embo J. 2002;21:3000–3008. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Dong ZM, Nomura M, Zhong S, Chen N, Bode AM, Dong Z. Signal transduction pathways involved in phosphorylation and activation of p70S6K following exposure to UVA irradiation. J Biol Chem. 2001a;276:20913–20923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ma WY, Kaji A, Bode AM, Dong Z. Requirement of ATM in UVA-induced signaling and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3124–3131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mattjus P, Schmid PC, Dong ZM, Zhong S, Ma WY, Brown RE, Bode AM, Schmid HH, Dong Z. Involvement of the acid sphingomyelinase pathway in uva-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001b;276:11775–11782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Jansen C, She QB, Goto H, Inagaki M, Bode AM, Ma WY, Dong Z. Ultraviolet B-induced phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 28 is mediated by MSK1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33213–33219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.