Abstract

Phosphorylation mediates the function of many proteins and enzymes. In the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, phosphorylation of Thr 197 in the activation loop strongly influences its catalytic activity. In order to provide theoretical understanding about this important regulatory process, classical molecular dynamics simulations and ab initio QM/MM calculations have been carried out on the wild-type PKA–Mg2 ATP–substrate complex and its dephosphorylated mutant, T197A. It was found that pThr 197 not only facilitates the phosphoryl transfer reaction by stabilizing the transition state through electrostatic interactions but also strongly affects its essential protein dynamics as well as the active site conformation.

Keywords: protein kinase A (PKA), phosphorylation of Thr 197, molecular dynamics, QM/MM calculations, collective motion

Protein phosphorylation controls a myriad of key biological processes in cellular pathways, ranging from metabolic pathways to cell cycle control and gene transcription (Johnson et al. 1996). The abnormal phosphorylation of cellular proteins has been associated with many human diseases (Blume-Jensen and Hunter 2001; Cohen 2001). Protein kinases, which catalyze the phosphoryl transfer reaction, are themselves regulated by phosphorylation. Due to its central importance, there is intense interest in understanding how phosphorylation modulates protein kinase activity (Johnson et al. 2001; Engh and Bossemeyer 2002; Adams 2003; Nolen et al. 2004).

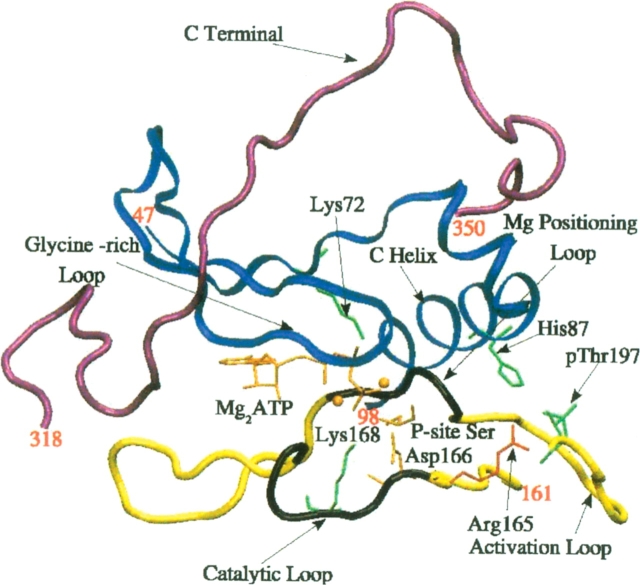

Among protein kinases, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) is the best characterized member and often serves as a paradigm for the entire family (Johnson et al. 2001). Its catalytic subunit has only ∼350 residues and forms a conserved bilobal structure (Hanks et al. 1988; Taylor and Radzio-Andzelm 1994; Bossemeyer 1995), as shown in Figure 1. Its conserved core consists of two lobes: a small lobe (residues 40–120) dominated by β-sheets, and a large lobe (residues 128–300) composed mostly of α-helices. Most of the highly conserved active site residues and residues involved in peptide binding are contributed by the large lobe. Mg2 ATP is bound in a deep cleft between the two lobes, with the adenosine portion deeply buried in a hydrophobic pocket.

Figure 1.

The structure of the ternary PKA–substrate complex. Ribbon representation of the catalytic subunit with the N terminus (purple), small-lobe core (blue), linker segment (red), large-lobe core (tan), and the C terminus (orange), including Mg2ATP (licorice representation) and a 20-residue peptide substrate (green) resulting from the original PDB.

In PKA, Thr 197 in the activation loop is always autophosphorylated for full activity. In a variety of crystal structures, it is 8–10 Å away from the catalytic site and forms several key contacts with charged residues from the large and small lobes (Johnson et al. 2001). The interaction with His 87 in the small lobe is proposed to contribute to the closure of the catalytic site (Adams 2003). pThr 197 also forms a hydrogen bond with the catalytic loop residue Arg 165, which makes contact with Asp 166, the catalytic base in the catalytic site (Fig. 2) (Valiev et al. 2003; Diaz and Field 2004; Cheng et al. 2005). The removal of the activation loop phosphorylation site by a T197A mutation reduces the phosphoryl transfer rate from >500 sec−1 to 3.6 sec−1, while it increases the Km for ATP by two orders of magnitude (Adams et al. 1995; Grant and Adams 1996).

Figure 2.

Schematic depiction of the active site cleft. Residues 47–98 in the small lobe (blue) displayed in ribbon representation, the linker and the region of β-sheet in the large lobe (residues 161–197, yellow), with the catalytic loop (residues 166–171) and the Mg2+ positioning loop (residues 184–187) highlighted (black). The position of the C-terminal tail that comes close to the activation site cleft (residues 318–350) is shown (purple).

Although experimental studies have revealed the importance of this activation loop phosphorylation, its regulatory mechanism is still elusive (Bossemeyer et al. 1993; Hubbard 1997; Engh and Bossemeyer 2001; Seifert et al. 2002; Adams 2003; Nolen et al. 2004). Several mechanisms have been proposed, including control of the active conformation (Nolen et al. 2004), modulation of the phosphoryl transfer step (Adams 2003), or formation of a P + 1 substrate binding site at the C-terminal end of the activation segment (Hubbard 1997; Engh and Bossemeyer 2001; Seifert et al. 2002).

In our previous QM/MM investigations (Cheng et al. 2005), we have studied the phosphoryl transfer reaction catalyzed by the wild-type PKA, and probed catalytic roles of individual residue contribution in enzyme catalysis. Based on barrier decomposition analysis, pThr 197 was found to contribute ∼2 kcal/mol to the electrostatic stabilization of the mainly dissociative transition state during the phosphoryl transfer reaction (see Fig. 8 in Cheng et al. 2005), which is qualitatively in agreement with experimental studies (Adams 2003). However, since the method of barrier decomposition analysis assumes that the mutation of individual residues does not change the enzyme structure, such an analysis is very preliminary, considering that the conformation change has been proposed as one possible mechanism for the activation loop phosphorylation (Nolen et al. 2004). Many questions remain unanswered, including: Does the autophosphorylation affect overall enzyme dynamics or influence the active site conformation, or both? Is the reaction barrier for T197A-mutated PKA–substrate complex really higher than the wild-type if structural relaxation has been taken into account? In order to answer those questions, more systematic computational studies should be carried out on both the wild-type and T197A-mutated PKA–substrate complexes. In the present work, by simulating the dynamics of PKA–substrate complexes, studying the phosphoryl transfer reaction with combined ab initio QM/MM methods, and analyzing the global molecular motions, we have provide more detailed understanding about how autophosphorylation of Thr 197 modulates the catalytic activity of PKA.

Figure 8.

Time dependence of the side-chain torsion angle χ1 of the P-site Ser in the R165A mutant.

Results and Discussion

Stability of the trajectories

The molecular dynamics simulations of the wild-type, T197A, and R165A mutated PKA models were carried out for 25 nsec, respectively. As a measure of the structural stability, root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) for all heavy atoms found in the original PDB file between each snapshot and the initial structure were calculated, as shown in Figure 3. We can see that each trajectory is stable after 2 nsec. Meanwhile, the temperature remains steady within 300 ± 1.2 K over the course of the simulations.

Figure 3.

Time dependence of RMS deviations of heavy atoms of the wild-type PKA, and T197A and R165A mutants during 25 nsec MD simulations, respectively.

Since there are an ATP ligand and the peptide substrate in the active cleft, we measured the distance between the Pγ atom of ATP and the hydroxyl atom OG of the P-site Ser to evaluate the stability of the substrate binding, as shown in Figure 4. Wild-type PKA–substrate complex shows quite stable dynamic characteristics, with the average distance between Pγ and OG at 3.95 ± 0.46 Å. The T197A mutant is stable for the first 16 nsec MD simulation, but the distance increases a bit to ∼5 Å after 22 nsec, which might correspond to the larger kpeptide and kATP in the T197A mutant (Adams et al. 1995). Meanwhile, the corresponding distance between ATP and the P-site Ser in the R165A mutant is <4 Å during the first 4 nsec of MD simulation and then jumps to ∼5 Å. This indicates that Arg 165 might play a role in the binding affinity of the substrate peptide. The following analyses focusing on the active site of the T197A mutant are based on the trajectories between 2 nsec and 22 nsec.

Figure 4.

Time dependence of the distance between ATP and the P-site Ser in the wild-type PKA, and T197A and R165A mutants during 25 nsec simulations, respectively.

Active-site configurations in the wild-type PKA and T197A mutant models

Generally there are three different rotameric states for the first dihedral angle χ1 of an amino acid side chain. They are the G+, G−, and T states (Fig. 5) (Sridhar et al. 1974; Verhoeven 1996). The distributions of the χ1 values of the P-site Ser during the MD simulations were calculated for the wild type and the T197A mutant, respectively. As shown in Figure 6, the G+ rotamer prevails in the MD trajectory of the wild-type PKA model, while G− is dominant in the T197A mutant. Similarly, due to the two different rotamer states of the P-site Ser, there are mainly two different configurations of the active site, as shown in Figure 5. The G+ rotamer features a hydrogen bond between the P-site Ser and Asp 166; the average distance between the OD2 atom of Asp 166 and OG of the P-site Ser is 3.77 ± 0.61 A. The average distance between OG and the Pγ atom of ATP is 3.89 ± 0.51 Å, and the angle of OG, Pγ, and Oβγ is ∼163 ± 9°. In contrast, for the G− rotamer, the P-site Ser forms a hydrogen bond with the nonbridging Oγ of ATP instead of Asp 166. The average distance between OG and OD2 is 4.74 ± 0.55 Å, and the average distance between OG and Pγ is 3.73 ± 0.47 Å, while the angle of OG, Pγ, and Oβγ is only ∼125 ± 14°. According to our previous study on the crystal structure (PDB code 1L3R) (Cheng et al. 2005), the G+ rotamer should be catalytically more active, with Asp 166 serving as the catalytic base. G− is more thermostable in the T197A mutant, in which the P-site Ser forms a hydrogen bond with the ATP. The result is consistent with the experimental observations of several X-ray crystal structures of both the PKA (Madhusudan et al. 1994) and phosphorylase kinase (Lowe et al. 1997; Skamnaki et al. 1999), as well as the thermostability analysis on PKA–substrate complexes (Herberg et al. 1999).

Figure 5.

The different rotameric states of a single amino acid and the corresponding stereo image of the active site residues of the wild-type PKA and T197A mutant interacting with ATP and the P-site Ser.

Figure 6.

The side-chain torsion angle distribution of the P-site Ser χ1 distributions in the wild-type PKA and T197A mutant.

The PMFs for the transition between the two rotamers have been calculated using the umbrella sampling technique and are displayed in Figure 7. In the absence of PKA, the G+rotamer is much more stable than the G−. The relative free energy difference is ∼1.4 kcal/mol, and the transition barrier from G+is ∼3.6 kcal/mol. In the wild-type PKA, the G+rotamer is more stable by <1 kcal/mol, and the transition barrier is ∼5 kcal/mol. In the T197A mutant, the G− is more stable, which is consistent with Figure 6.

Figure 7.

The free energy barriers for the reorientation of the side chain of the P-site Ser in the wild-type and T197A-mutated PKA–substrate complex.

As shown in Figure 2, the residue Arg 165 is directly connected to both pThr 197 and Asp 166, the catalytic base in the active site. In order to test whether pThr 197 regulates the active site conformation through Arg 165, a 15-nsec MD simulation on the R165A mutant has been carried out. From Figure 8, it can be seen that the side-chain conformations of the P-site Ser in the R165A mutant are similar to that in the wild-type PKA, although the replacement of Arg 165 with Ala disconnects the interactions between the pThr 197 and the active site. This result suggests that pThr 197 does not affect the side-chain conformation of the P-site Ser via Arg 165, although the P-site Ser binding affinity has been weakened with the replacement of Arg 165 with Ala (Fig. 4), which is consistent with the conclusion from a recent structural analysis (Nolen et al. 2004).

The phosphoryl transfer reaction barrier

To quantitatively describe the effect of activation loop phosphorylation on the phosphoryl transfer reaction barrier, we have calculated the reaction barriers with different initial structures for both the wild type and the T197A mutant with DFT QM/MM calculations. Despite the two different conformations in the active site, our QM/MM studies indicate that only the G+conformation can directly participate in the phosphoryl transfer reaction, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. It is necessary that Asp 166 is available as the catalytic base to accept the hydro-xyl proton in the late stages of the phosphoryl transfer. In the G− conformation, the P-site Ser must always first rotate its side chain to the favorable G+ to form a hydrogen bond with Asp 166, and then it can participate in the phosphoryl transfer reaction.

Table 1.

Energy barriers for the phosphoryl transfer reaction in the wild-type PKA enzyme

The energy unit is kcal/mol, the distance unit is Å, and the angle unit is °.

aThe method used for the QM subsystem is the single-point B3LYP/6–31+G* calculation based on the geometrics optimized at the B3LYP/6–31G* level.

Table 2.

Activation barriers for the phosphoryl transfer reaction in the T197A mutant

The energy unit is kcal/mol, the distance unit is Å, and the angle unit is °.

aThe method used for the QM subsystem is the single-point B3LYP/6–31+G* calculation based on the geometrics optimized at the B3LYP/6– 31G* level.

bHere, 9001 and 10001 correspond to the snapshots at 10 nsec and 11 nsec, respectively.

The calculated reaction barriers for wild-type PKA and the T197A mutant are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. We can see that different initial structures lead to fluctuations in the reaction energy barriers. The average QM/MM reaction barrier for the phosphoryl transfer is 13.7 ± 2.2 kcal/mol for the wild-type PKA, while it is 17.0 ± 2.9 kcal/mol for the T197A mutant. The average barriers are quite consistent with the experimental reaction rate constants for the phosphoryl transfer step, which are 500 sec−1 and 3.6 sec−1 for the wild type and the T197A mutant, respectively (Zhou and Adams 1997). It should be noted that any single calculation of the barrier is not necessarily close to the average, and it is not meaningful to compare the individual barriers between the wild-type PKA and the T197A mutant since their initial structures are quite different. In addition, we have calculated the contribution of pThr 197 and Ala 197 to the transition state stabilization based on the geometries of all the QM/MM models of the wild type and T197A mutant, respectively. Our calculations indicate that on average the pThr 197 in the wild-type PKA contributes ∼−3.4 ± 0.9 kcal/mol to stabilize the transition state in comparison with the reactant, while the contribution of Ala 197 in the T197A mutant is <−0.2 kcal/mol. This result is quite consistent with the difference in the average reaction energy barrier, which indicates that pThr 197 plays an important role in facilitating the phosphoryl transfer reaction through the electrostatic stabilization of the transition state.

Cross-correlation analysis for the wild type and T197A mutant

In order to reveal the correlated motions, we have calculated a two-dimensional dynamical cross-correlation map (DCCM) for all the Cα atoms in the C subunit of PKA (residues 14–350) using the wild-type and the T197A mutant MD trajectories, respectively, as shown in Figure 9. The snapshots used were between 2 nsec and 22 nsec.

Figure 9.

Calculated residue–residue-based correlated motions within 2–20 nsec MD simulations of the wild-type PKA and T197A mutant. (A) Wild-type PKA, (B) T197A mutant.

From Figure 9, we can see that the two dynamical cross-correlation maps are quite different. In the wild-type PKA, the dynamics of the small lobe (residues 14–119) and the C terminal (residues 300–350) are strongly correlated. Several loops, such as the catalytic loop (resi-dues 166–171) and the Mg2+ positioning loop (residues 184–187), display strongly correlated motion with the small lobe as well. However, the region of the hinge between the small and large lobes and the G-helix (residues 241–260) in the large lobe are anti-correlated with the small lobe and the C terminus. This observation is quite consistent with the catalytic activity of the wild-type PKA. In the ATP binding pocket, the glycine-rich loop (residues 47–58), the catalytic loop, and the Mg2+ positioning loop all directly bind with the substrate ATP. The correlated motion reflects the stronger substrate binding, which might help to stabilize the G+ configuration discussed above. However, in the T197A mutant, the correlated motions have been weakened significantly (Fig. 9B). It indicates that pThr 197 may be an important bridge connecting the small lobe with the large lobe, which could facilitate cooperative operation of the two lobes during the enzyme action.

Collective modes of motion in the wild type and T197A mutant

We have performed principal component analysis to calculate and to visualize the essential modes of motion using both the MD trajectories in the time interval of 2–22 nsec of the wild-type and the T197A-mutated PKA.

To eliminate the noise of the N and C termini, we truncated the first and last 10 residues in both PKA structures. In other words, 317 backbone Cα atoms were sampled over 20,000 consecutive structures with a time increment of 1 psec. The analysis below indicates that our results are consistent with the above cross-correlation analysis and has provided more detailed information regarding the internal motions of the different subunits.

The PCA averaged in the time interval of 10–22 nsec agrees with results in the time interval of 2–22 nsec. The corresponding figures of the wild-type PKA are in the Supplemental Material (not shown for the T197A mutant). The agreement between the two different time intervals suggests that a converged picture of the collective motions emerges for the last 12 nsec. Overall, salient PCA motion modes, in sufficiently converged MD simulations, reveal the dynamic characteristics of the protein.

For the wild-type PKA, the first two eigenvectors account for ∼87% of the motion observed in the first 22 nsec of the simulation trajectory, with cosine contents (Hess 2000) of 46% and 65%, respectively. The relative contributions of different eigenvectors to the overall motion are shown in Figure 10. These eigenvectors for the PKA (except the first and last 10 residues of the N terminus and the C terminus, respectively) are shown in Figure 11, panels A and B, with the stick-cone representation.

Figure 10.

Relative contributions of different modes (eigenvectors) to the overall motion are shown for the wild type and T197A mutant. The data are renormalized so that the eigenvalues for each set add up to unity.

Figure 11.

Principal dynamic modes of the wild-type PKA. (A,B) Porcupine plots of the first two most substantial principal motions of the wild-type PKA, respectively. The blue color represents the small lobe; purple, the activation segment; lime, the large lobe; white, the C terminus; and pink, the substrate peptide.

The most significant motion of the wild-type PKA in the context of a PKA–substrate complex is a “breathing” mode (Fig. 11A) with the two domains of the protein moving in opposition around the “hinge” region (residues 120–127). This region forms its own interaction with the edge of the ATP molecule and connects the N- and C-terminal lobes, each of which independently contributes a surface to the ATP binding site. Strikingly, the activation segment, shown in purple, shows a similar but less pronounced motion as the small lobe, which is consistent with our above cross-correlation analysis. By far the biggest contributor is this breathing mode. The axis of this motion is through a conserved residue, Arg 171. As the protein kinase breathes, the active site, including the activation segment, opens and closes. The second most significant internal motion is a mixture of rotation and twisting between the two lobes. As shown in Figure 11B, the twisting motion is around an axis perpendicular to the most significant motion mode, in which the active segment together with the rest of the residues in the large lobe move in the opposite direction with the small lobe. A similar motion has also been found in a study of ADP release (Lu et al. 2005).

In comparison with the wild-type PKA, the collective motions in the T197A mutant are quite different (Fig. 12A–C). The first three eigenvectors contribute to 49%, 29%, and 9% in the overall modes. The first most significant motion corresponds to a translation-like mode. The second and the third correspond to the rotation-like twisting motions. These three motions don't include interdomain twisting, which might control the opening and closing of the active site. This result indicates that the replacement of pThr 197 not only directly disrupts part of the hydrogen-bonding network between the small and large lobes but also dramatically affects the internal motion, which might play an important role in regulating the active site conformations.

Figure 12.

Principal dynamic modes of T197A mutant. (A–C) The first three most substantial principal motions of the T197A mutant.

Conclusions

The role of the phosphorylated Thr 197 in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase has been investigated and discussed with both molecular dynamics and density functional theory QM/MM calculations. The P-site Ser mainly occupies the active G+ state in the wild-type PKA, but the alternate rotamer G− in the T197A mutant. The transition barrier between the two states is ∼5 kcal/mol. Phosphoryl transfer can only take place with the active G+ conformation. In the T197A mutant, the inactive G− P-site Ser dominates the MD trajectory; therefore, conformational changes must accompany the catalytic turnover.

We have calculated B3LYP/(6–31+G*) QM/MM barriers for both the wild-type PKA and the T197A mutant with multiple initial structures. The simple averages of the nine activation barriers are 13.7 ± 2.2 kcal/mol for the wild-type PKA, and 17.0 ± 2.9 kcal/ mol for the T197A mutant. The results are consistent with experimental reaction rates from kinetic studies. By comparison, although the autophosphorylation of Thr 197 doesn't substantially affect the fold of the activation segment, the electrostatic interaction with the active site contributes to the stabilization of the transition state and activation of the wild-type PKA, which is consistent with our previous results using two PKA–substrate crystal structures, providing a synergistic understanding to the role of pThr 197 (Cheng et al. 2005).

Our molecular dynamics simulations find different collective motion modes between the wild-type PKA and T197A mutant. The interdomain twisting motion is captured only in the wild-type PKA, which might contribute to the opening and the closing of the active site. Cross-correlation analysis on both the wild-type PKA and T197A mutant further confirms the correlated motions between the small and large domains in the wild-type PKA. However, such correlation has been substantially weakened in the T197A mutant. Overall, our results indicate that pThr 197 not only facilitates the phosphoryl transfer reaction by electrostatically stabilizing the transition state but also strongly affects its essential protein dynamics as well as its active site conformation.

Materials and methods

In the current study, we employed the pseudobond ab initio QM/MM approach (Zhang et al. 1999, 2000, 2002b; Zhang 2005a,b), which has been demonstrated to be powerful in the study of several enzymes, including enolase (Liu et al. 2000), acetylcholinesterase (Zhang et al. 2002a, 2003), and 4oxalocrotonate tautomerase (Cisneros et al. 2003, 2004). Throughout the study, the charged phosphate groups were included in the QM subsystem and were calculated at a B3LYP/6–31G* level. Such a level of calculation is similar to that used in other contemporary studies (Valiev et al. 2003; Diaz and Field 2004).

Preparation of the initial PKA–substrate complex and the procedures of the molecular dynamics simulation and QM/ MM calculations, have been described in detail in our previous paper (Cheng et al. 2005). Here we only highlight several key points.

Molecular dynamics simulation

The preparation of the initial wild-type PKA–substrate complex was based on the 1L3R crystal structure (Madhusudan et al. 2002) and has already been described in detail in our previous paper (Cheng et al. 2005). For the T197A mutated model, pThr 197 was replaced with Ala in Tripos Inc.’s SYBYL7.0 (syb, α). Based on the pKa calculation with WHAT IF, His 87 has a neutral charge with only Nδ protonated. Therefore, including water molecules, there are 40,332 and 40,592 atoms in the wild-type and T197A mutated models, respectively. In order to test whether pThr 197 regulates the active site conformation through hydrogen bonding via Arg 165, we have prepared an R165A mutant system. Including water molecules, there are 40,338 atoms in this model.

For each system, the minimization, equilibration, and simulation procedures were exactly the same as in Cheng et al. (2005). Here we only highlight several key points. Molecular dynamics simulation with periodic boundary conditions were conducted using the Amber 7.0 package (D.A. Case et al., University of California, San Francisco). The charge parameters of Mg2ATP, phosphorylated serine, and threonine were determined in Cheng et al. (2005). All other force field parameters were from the parm99 parameter set (Cornell et al. 1995) and the polyphosphate parameters developed by Meagher et al. (2003). A default cutoff radius of 8 Å was introduced for nonbonded interactions, updating the neighbor pair list every 10 steps. The electrostatic interactions were calculated with the Particle Mesh Ewald method (Darden et al. 1993), and the SHAKE algorithm (Ryckaert et al. 1977) was used to constrain all bond lengths involving hydrogens. The simulations were performed under the constant pressure 1 atm and the constant temperature 300 K.

Umbrella sampling

In order to calculate the potential of mean force (PMF) along the first side-chain torsion angle OG-Cβ-Cα-N (χ1) of the P-site Ser, the umbrella sampling technique (Torrie and Valleau 1974; Valleau and Torrie 1977; Bartels and Karplus 1998) was employed. The potential energy of the system was biased with a harmonic potential ½ K (χ1;−χ1;,j)2 centered on successive values of χ1;i, where K is the harmonic force constant. A total of 36 windows were employed, centered on −180°, −170°, …, 170° with a harmonic force constant K of 30 kcal/mol–rad2. For each window, MD simulation consisted of 50 psec equilibration and 200 psec sampling. A time step of 1 fsec was used. From these 36 biased simulations, the PMF was obtained with the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) (Kumar et al. 1992). The self-consistent set of equations was iterated until changes in the free energy constants Fi were <0.1 kcal/mol.

QM/MM study

The phosphate transfer reaction step in both wild-type PKA and the T197A mutant was studied using a pseudobond ab initio QM/MM approach (Zhang et al. 1999, 2000, 2002b, 2005a,b). In order to take account of enzyme dynamics, multiple ab initio QM/MM minimum reaction energy pathways were computed in two steps (Zhang et al. 2003): generating enzyme–substrate conformations with molecular dynamics simulation, and determining the QM/MM reaction energy barrier for each initial structure as described in our previous study (Cheng et al. 2005).

From MD trajectories of the wild type and the T197A mutant, respectively, nine equally spaced snapshots at 2, 3, …, 10 nsec have been chosen as initial structures for QM/ MM studies. For the T197A mutant, the optimization procedure failed to get a converged reactant structure for the snapshot at 9 nsec, so that an additional snapshot at 11 nsec was chosen. Since we are interested in the active site, the water molecules beyond 27 Å of the Pδ atom of ATP were removed in our QM/MM system, and only atoms within 20 Å of the Pδ atom of ATP were allowed to move in QM/MM minimizations. Thus, each QM/MM system consists of PKA, ATP, SP20 (peptide), and ∼2700 water molecules, a total of ∼10,000 atoms. Each initial structure for the QM/MM study was first energy-minimized with the MM method. The criterion used for convergence is the root-mean-square (RMS) energy gradient being <0.1 kcal mol−1Å−1.

In the QM/MM studies, each QM subsystem consists of the triphosphate arm of ATP, side chains of P-site Ser, Asp 166, and Lys 168, and two Mg2+ ions for a total of 49 atoms, while the rest are MM atoms. Enzyme reaction paths were determined by B3LYP/(6–31G*) QM/MM calculations with an iterative minimization procedure and reaction coordinate driving method (Zhang et al. 2000). Frequency calculations have been carried out to characterize the reactant, transition state, and intermediate. In addition, single point B3LYP/(6–31+G*) QM/MM calculations have been carried out to calculate their energy differences. Throughout the QM/MM calculations, pseudobonds were treated with the 3–21G basis set and its corresponding effective core potential parameters (Zhang et al. 1999). The calculations were carried out using modified versions of the Gaussian98 (Gaussian, Inc.) and TINKER (http://dasher.wustl.edu/tinker) programs. For the QM sub-system, criteria used for geometry optimizations follow Gaussian98 defaults. For the MM subsystem, the convergence criterion used is to have the RMS energy gradient be <0.1 kcal mol−1Å−1. No cutoff for nonbonded interactions was used in the QM/MM calculations. This QM/MM calculation protocol was demonstrated to be successful with our wild-type models (Cheng et al. 2005).

Cross-correlation analysis

In order to investigate the correlated motion between different regions of a protein, such as the domain–domain communication (McCammon and Harvey 1986; Ichiye and Karplus 1991; Swaminathan et al. 1991; Radkiewicz and Brooks 2000; Rod et al. 2003), we have calculated cross-correlation coefficients for Ca displacements using wild-type and T197A mutant MD trajectories, respectively. The snapshots used were between 2 nsec and 22 nsec. The cross-correlation coefficient Corr(i, j) is given by:

Δri is the vector displacement from the mean position of the Cα atom in residue i. The angle brackets denote an ensemble average. Corr(i, j) can be collected in matrix form and displayed as a two-dimensional dynamical cross-correlation map (DCCM) (Swaminathan et al. 1991). A positive value of Corr(i, j) indicates that two atoms move in the same direction, whereas a negative value signals anticorrelated motion. In order to remove translational and rotational motion of the protein complex, we first moved the center of mass for each structure to the origin, and then employed the quaternion method to superimpose Cα atoms in each snapshot to the first structure in the production run.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a powerful approach to reduce the dimensionality of a data set. When applied to analyze a MD simulation trajectory (Ichiye and Karplus 1991; Garcia 1992; Amadei et al. 1993; Hayward et al. 1993; Balsera et al. 1996; Becker 1997; Tai et al. 2001), it can separate large-scale collective motions from random thermal fluctuations. PCA analysis is based on the covariance matrix

where ri,rj are Cartesian coordinates of atom i and j, respectively. 〈(quantity)〉t represents the average over the whole MD trajectory. The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix yield the collective dynamic modes and their amplitudes.

The ptraj program in the Amber 8 package was employed to calculate covariance matrix elements. Since the diagonalization of the matrix for all atoms was found to exceed the memory capacity of the computer, only Cα atoms of both the PKA and peptide substrate were included in the analysis. We have employed porcupine plots (Tai et al. 2001) to visualize the collective dynamic modes. In this case, the functionally important motions include the opening of the active cleft and the interdomain twisting, etc.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by grants from the NSF and NIH. Additional support has been provided by NBCR, CTBP, HHMI, the W.M. Keck Foundation, and Accelrys, Inc. Y.Z. thanks NYSTAR for a James D. Watson Young Investigator award.

Footnotes

Supplemental material see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: Yuhui Cheng, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Department of Pharmacology, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0365, USA; e-mail: ycheng@mccammon.ucsd.edu; fax: (858) 534-4974.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051852306.

References

- Adams J.A. 2003. Activation loop phosphorylation and catalysis in protein kinases: Is there functional evidence for the autoinhibitor model? Biochemistry 42: 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J.A., McGlone M.L., Gibson R., Taylor S.S. 1995. Phosphorylation modulates catalytic function and regulation in the cAMP-dependent protein-kinase Biochemistry 34: 2447–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A., Linssen A.B.M., Berendsen H.J.C. 1993. Essential dynamics of proteins Proteins 17: 412–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsera M.A., Wriggers W., Oono Y., Schulten K. 1996. Principal component analysis and long time protein dynamics J. Phys. Chem. 100: 2567–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels C. and Karplus M. 1998. Probability distributions for complex systems: Adaptive umbrella sampling of the potential energy J. Phys. Chem. B 102: 865–880. [Google Scholar]

- Becker O.M. 1997. Geometric versus topological clustering: An insight into conformation mapping Proteins 27: 213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume-Jensen P. and Hunter T. 2001. Oncogenic kinase signalling Nature 411: 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossemeyer D. 1995. Protein-kinases—Structure and function FEBS Lett. 369: 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossemeyer D., Engh R.A., Kinzel V., Ponstingl H., Huber R. 1993. Phospho-transferase and substrate binding mechanism of the cAMP-dependent protein-kinase catalytic subunit from porcine heart as deduced from the 2.0-Å structure of the complex with Mn2+adenylyl imidodiphosphate and inhibitor peptide PKI(5-24) EMBO J. 12: 849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Zhang Y., McCammon J.A. 2005. How does the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalyze the phosphorylation reaction: An ab initio QM/MM study J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127: 1553–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros G.A., Liu H., Zhang Y., Yang W. 2003. Ab initio QM/ MM study shows there is no general acid in the reaction catalyzed by 4-oxalocrotonate tautornerase J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125: 10384–10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros G.A., Wang M., Silinski P., Fitzgerald M.C., Yang W. 2004. The protein backbone makes important contributions to 4-oxalo-crotonate tautomerase enzyme catalysis: Understanding from theory and experiment Biochemistry 43: 6885–6892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. 2001. The role of protein phosphorylation in human health and disease. The Sir Hans Krebs Medal Lecture Eur. J. Biochem. 268: 5001–5010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell W.D., Cieplak P., Bayly C.I., Gould I.R., Merz K.M., Ferguson D.M., Spellmeyer D.C., Fox T., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A. 1995. A 2nd generation force-field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic-acids, and organic-molecules J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117: 5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. 1993. Particle mesh ewald—An n.log(n) method for ewald sums in large systems J. Chem. Phys. 98: 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz N. and Field M.J. 2004. Insights into the phosphoryl-transfer mechanism of cAMP-dependent protein kinase from quantum chemical calculations and molecular dynamics simulations J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126: 529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh R.A. and Bossemeyer D. 2001. The protein kinase activity modulation sites: Mechanisms for cellular regulation—Targets for therapeutic intervention Adv. Enzyme Regul. 41: 121–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2002. Structural aspects of protein kinase control—Role of conformational flexibility Pharmacol. Ther. 93: 99–111 ——. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A.E. 1992. Large-amplitude nonlinear motions in proteins Phys. Rev. Lett. 68: 2696–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B.D. and Adams J.A. 1996. Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of cAMP-dependent protein kinase using rapid quench flow techniques Biochemistry 35: 2022–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks S.K., Quinn A.M., Hunter T. 1988. The protein-kinase family—Conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domains Science 241: 42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward S., Kitao A., Hirata F., Go N. 1993. Effect of solvent on collective motions in globular protein J. Mol. Biol. 234: 1207–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberg F.W., Doyle M.L., Cox S., Taylor S.S. 1999. Dissection of the nucleotide and metal-phosphate binding sites in cAMP-dependent protein kinase Biochemistry 38: 6352–6360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B. 2000. Similarities between principal components of protein dynamics and random diffusion Phys. Rev. E 62: 8438–8448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S.R. 1997. Crystal structure of the activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in complex with peptide substrate and ATP analog EMBO J. 16: 5572–5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiye T. and Karplus M. 1991. Collective motions in proteins—A covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular-dynamics and normal mode simulations Proteins 11: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.N., Noble M.E.M., Owen D.J. 1996. Active and inactive protein kinases: Structural basis for regulation Cell 85: 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D.A., Akamine P., Radzio-Andzelm E., Madhusudan E., Taylor S.S. 2001. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase Chem. Rev. 101: 2243–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Bouzida D., Swendsen R.H., Kollman P.A., Rosenberg J.M. 1992. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. 1. The method J. Comput. Chem. 13: 1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang Y., Yang W. 2000. How is the active site of enolase organized to catalyze two different reaction steps? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122: 6560–6570. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe E.D., Noble M.E.M., Skamnaki V.T., Oikonomakos N.G., Owen D.J., Johnson L.N. 1997. The crystal structure of a phosphorylase kinase peptide substrate complex: Kinase substrate recognition EMBO J. 16: 6646–6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B., Wong C.F., McCammon J.A. 2005. Release of ADP from the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A: A molecular dynamics simulation study Protein Sci. 14: 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudan J.A., Trafny E.A., Xuong N.H., Adams J.A., Ten Eyck L.F., Taylor S.S., Sowadski J.M. 1994. cAMP-dependent protein kinase crystallographic insights into substrate recognition and phosphotransfer Protein Sci. 3: 176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudan J.M., Akamine P., Xuong N.H., Taylor S.S. 2002. Crystal structure of a transition state mimic of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase Nat. Struct. Biol. 9: 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCammon J.A. and Harvey S.C. In Dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids. . 1986. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Meagher K.L., Redman L.T., Carlson H.A. 2003. Development of polyphosphate parameters for use with the amber force field J. Comput. Chem. 24: 1016–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen B., Taylor S., Ghosh G. 2004. Regulation of protein kinases: Controlling activity through activation segment conformation Mol. Cell 15: 661–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radkiewicz J.L. and Brooks C.L. 2000. Protein dynamics in enzymatic catalysis: Exploration of dihydrofolate reductase J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122: 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rod T.H., Radkiewicz J.L., Brooks C.L. 2003. Correlated motion and the effect of distal mutations in dihydrofolate reductase Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 6980–6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. 1977. Numerical-integration of cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints—Molecular-dynamics of n-alkanes J. Comput. Phys. 23: 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert M.H.J., Breitenlechner C.B., Bossemeyer D., Huber R., Holak T.A., Engh R.A. 2002. Phosphorylation and flexibility of cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) using p-31 NMR spectroscopy Biochemistry 41: 5968–5977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skamnaki V.T., Owen D.J., Noble M.E.M., Lowe E.D., Lowe G., Oikonomakos N.G., Johnson L.N. 1999. Catalytic mechanism of phosphorylase kinase probed by mutational studies Biochemistry 38: 14718–14730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar C.G., Hines W.A., Samulski E.T. 1974. Polypeptide liquidcrystals—Magnetic-susceptibility, twist elastic-constant, rotational viscosity coefficient, and poly-γ-benzyl-L-glutamate sidechain conformation J. Chem. Phys. 61: 947–953. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan S., Harte W.E., Beveridge D.L. 1991. Investigation of domain-structure in proteins via molecular-dynamics simulation—Application to HIV-1 protease dimer J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113: 2717–2721. [Google Scholar]

- Tai K., Shen T., Borjesson U., Philippopoulos M., McCammon J.A. 2001. Analysis of a 10-ns molecular dynamics simulation of mouse acetylcholinesterase Biophys. J. 81: 715–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S.S. and Radzio-Andzelm E. 1994. Three protein-kinase structures define a common motif Structure 2: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrie G.M. and Valleau J.P. 1974. Monte-Carlo free-energy estimates using non-Boltzmann sampling—Application to subcritical Lennard-Jones fluid Chem. Phys. Lett. 28: 578–581. [Google Scholar]

- Valiev M., Kawai R., Adams J.A., Weare J.H. 2003. The role of the putative catalytic base in the phosphoryl transfer reaction in a protein kinase: First-principles calculations J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125: 9926–9927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valleau J.P. and Torrie G.M. In A guide for Monte Carlo for statistical mechanics. . 1977. Plenum Press, Inc, New York.

- Verhoeven J.W. 1996. Glossary of terms used in photochemistry Pure Appl. Chem. 68: 2223–2286. [Google Scholar]

- http://jcp.aip.orgZhang Y. 2005a. Improved pseudobonds for combined ab initio quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical methods J. Chem. Phys. 122:. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2005b. Pseudobond ab initio QM/MM approach and its applications to enzyme reactions Theor. Chem. Acc —— (in press).

- Zhang Y., Lee T.S., Yang W. 1999. A pseudobond approach to combining quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical methods J. Chem. Phys. 110: 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu H., Yang W. 2000. Free energy calculation on enzyme reactions with an efficient iterative procedure to determine minimum energy paths on a combined ab initio QM/MM potential energy surface J. Chem. Phys. 112: 3483–3492. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Kua J., McCammon J.A. 2002a. Role of the catalytic triad and oxyanion hole in acetylcholinesterase catalysis: An ab initio QM/MM study J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124: 10572–10577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu H., Yang W. 2002b. Ab initio QM/MM and free energy calculations of enzyme reactions In Computational methods for macromolecules: Challenges and applications (eds. Schlick T. and Gan H.H.) . pp. 332–354. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Zhang Y., Kua J., McCammon J.A. 2003. Influence of structural fluctuation on enzyme reaction energy barriers in combined quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical studies J. Phys. Chem. B 107: 4459–4463. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. and Adams J.A. 1997. Is there a catalytic base in the active site of cAMP-dependent protein kinase? Biochemistry 36: 2977–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]