Abstract

Background

Snake venoms are complex mixtures of pharmacologically active proteins and peptides which belong to a small number of superfamilies. Global cataloguing of the venom transcriptome facilitates the identification of new families of toxins as well as helps in understanding the evolution of venom proteomes.

Results

We have constructed a cDNA library of the venom gland of a threatened rattlesnake (a pitviper), Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii (Desert Massasauga), and sequenced 576 ESTs. Our results demonstrate a high abundance of serine proteinase and metalloproteinase transcripts, indicating that the disruption of hemostasis is a principle mechanism of action of the venom. In addition to the transcripts encoding common venom proteins, we detected two varieties of low abundance unique transcripts in the library; these encode for three-finger toxins and a novel toxin possibly generated from the fusion of two genes. We also observed polyadenylated ribosomal RNAs in the venom gland library, an interesting preliminary obsevation of this unusual phenomenon in a reptilian system.

Conclusion

The three-finger toxins are characteristic of most elapid venoms but are rare in viperid venoms. We detected several ESTs encoding this group of toxins in this study. We also observed the presence of a transcript encoding a fused protein of two well-characterized toxins (Kunitz/BPTI and Waprins), and this is the first report of this kind of fusion in a snake toxin transcriptome. We propose that these new venom proteins may have ancillary functions for envenomation. The presence of a fused toxin indicates that in addition to gene duplication and accelerated evolution, exon shuffling or transcriptional splicing may also contribute to generating the diversity of toxins and toxin isoforms observed among snake venoms. The detection of low abundance toxins, as observed in this and other studies, indicates a greater compositional similarity of venoms (though potency will differ) among advanced snakes than has been previously recognized.

Background

The advanced snakes (superfamily Colubroidea) consist of a monophyletic group of four families: Atractaspididae, "Colubridae", Elapidae and Viperidae [1]. These snakes have evolved biochemical weapon (toxins), rather than mechanical means of handling prey. Phylogenetic studies show that the venom gland (where toxins are produced) evolved once at the base of the Colubroidea about 60–80 million years ago and has undergone extensive "evolutionary tinkering" of delivery systems and compositions of venom [2,3]. Phylogenetic reconstruction between toxin genes and snake families showed that the recruitment of toxin families into the venom gland has occurred multiple times by both basal (e.g. metalloproteinases, CRISP, Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitors, NGF) and independent (e.g. PLA2, natriuretic peptides) recruitment events [4]. Approximately 26 families of toxins have been catalogued in snake venom proteomes, and several families appear to be specific to a particular family of venomous snakes (Additional file 1). Sarafotoxins are found only in venoms of Atractaspididae; serine proteinases related to blood coagulation factors Xa, cobra venom factor, waprins and AVIT (prokineticin) family peptides appear to be limited to the Elapidae; and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), disintegrins, waglerins, dipeptidyl peptidase IV and crotamine occur primarily in venoms of the Viperidae (Additional file 1). The occurrence, relative abundance and pharmacological potency of various members of these toxin families in venom make envenomation remarkably complex. Envenomation by elapid snakes is usually characterized by rapid neurotoxic complications due to presence of large amounts of postsynaptic neurotoxins [5], while envenomation by viperid snakes evokes complex hemorrhagic, hypotensive and inflammatory effects caused by the actions of numerous serine proteinases, metalloproteinases and C-type lectins (CLP) [6-9]. Effects of envenomation by snakes in the genus Atractaspis can include vasoconstriction, resulting in cardiac arrest [10]. Despite overall similarity in clinical symptoms exhibited after envenomation by members of a particular family of snakes, there exists considerable species-specific variation in absolute effects within each group, contributing to the difficulty in assessing and treating envenomated victims.

Previously, identification and characterization of venom components relied primarily on various methods in protein chemistry or on cloning of individual genes. However, neither approach is well-suited to detect toxins that are found in low abundance. Therefore, the apparent absence of a particular family of toxins from venom could be due either to their very low abundance or to the lack of expression in the venom gland. The genes of low abundance toxins are best discovered by the construction of a cDNA library and sequencing of a sizeable number of ESTs. Using this approach, new toxin genes in known families as well as several completely new families of toxins have been discovered, and the spectrum of snake toxin proteome is gradually expanding [11-28]. To search for novel and low abundance toxin genes or new families of toxins, we constructed a cDNA library and sequenced ESTs from the venom gland of Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii (Desert Massasauga).

Sistrurus catenatus (Massasauga Rattlesnake) is a small pitviper broadly distributed across the North American prairies from Ontario, Canada and New York to extreme southeastern Arizona, with an apparently disjunct population in northern Chihuahua, Mexico [29,30]. One subspecies, S. c. edwardsii (Desert Massasauga), occurs primarily in arid and desert grasslands, occasionally occurring in dune formations and desert scrub [31-33]. Populations of S. catenatus generally are threatened or declining rangewide, primarily as a result of habitat loss and human encroachment, and therefore endangered species status has been recommended [34,35]. In a systematic study, Holycross and Mackessy [33] showed that among Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico populations of S. c. edwardsii, lizards are the major prey, followed by small mammals and centipedes. In the present work, the venom gland has been collected from snakes originating from the Colorado population.

General symptoms of envenomation resulting from many North American pitvipers bite are pain, local tissue effects (progressive edema, erythema and necrosis) with coagulopathy (hypofibrinogenemia and prolongation of prothrombin time) and thrombocytopenia as systemic effects. However, there is no specific report to date in the literature concerning envenomation by S. c. edwardsii. Profiling of toxin expression of this threatened snake species will give a global view for the expression of all genres of toxins, including variation in coding/noncoding sequences and their evolutionary trends. The results of this study will also help in the understanding of envenomation processes of rattlesnake bites, which in turn will be important for more effective clinical treatment and antivenom management in cases of snakebite.

Results and Discussion

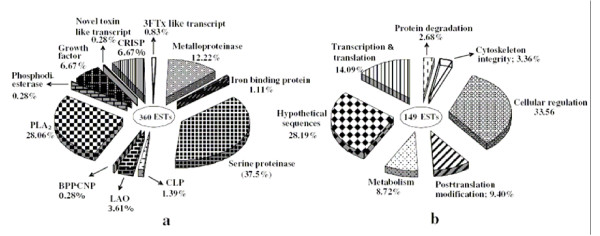

A total of 518 out of 576 ESTs produced readable sequences. The sizes of sequences showed a distribution between 300 and 2000 base pairs, with an average of 800 base pairs (data not shown). A total of 232 clusters were obtained and subsequently all clusters checked manually (Table 1; Figures 1a and 1b and Additional files 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Distribution of 576 ESTs sequenced from S. c. edwardsii venom gland in toxin and toxin-like transcript, cellular protein, mitochondrial and hypothetical sequence clusters.

| Transcripts category | Number of ESTs | Number of clusters | Redundancy (clones/cluster) | Representation over total clones (%) | Representation over matching clones (%) |

| Toxin | 360 | 76 | 4.74 | 69.40 | 77 |

| Cellular | 107 | 106 | 1.04 | 20.65 | 23 |

| Mitochondrial | 9 | 9 | 1.00 | 1.73 | - |

| Hypothetical | 42 | 42 | 1.00 | 8.10 | - |

The variations observed among toxin isoforms in this library are not due to population level diversity as they are derived from the venom gland of a single snake

Figure 1.

The transcriptome profile of the venom gland of S. c. edwardsii. Abundance of (a) toxins and toxin-like transcript clusters, and (b) cellular proteins and hypothetical sequences clusters. Percentage of total ESTs for each category are shown.

A large number of ESTs matched with snake toxins (360 ESTs in 76 clusters; 69.4%). Others code for cellular (non-toxin) proteins (107 ESTs in 106 clusters; 20.65%), and 42 hypothetical ESTs (8.1%). Nine ESTs (1.7%) matched with mitochondrial genes. Fifteen ESTs did not significantly match with any sequence available in non-redundant databases. Further, they do not have any ORFs and may represent either long UTRs (3' or 5') or regulatory RNAs and may have important functions in the rapidly expressing gland tissues. The library contains a large portion of putative toxin genes (69.4%) compared to the cellular EST population (20.6%). We determined the complete sequence of the longest EST of each cluster and sequences were confirmed by repeated sequencing. We completed the sequencing for all major toxins and two low abundant toxin-like transcripts (described below). The existence of genes of particular interest, especially singletons, was confirmed by RT-PCR, using a separate pool of RNA that was used to make cDNA library as template, followed by sequencing.

Confirmation of species

Taxonomic identification at the molecular level is essential to ensure species identity [36], and 12S and 16S mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs are commonly used in the classification of snakes [37]. Three ESTs for the 12S RNA gene (DQ464268, Additional file 4) in our library show 100% identity to the reported S. c. edwardsii ribosomal sequence (AF057227) [38], confirming the venom gland used to make the library is of S. c. edwardsii origin. Interestingly, we observed that the ribosomal RNA sequence has poly(A) tail and therefore they appeared in the cDNA library. Polyadenylation of ribosomal RNA has been observed in yeast (Candida albicans), fungus (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), protistan parasites (Leishmania braziliensis and L. donovani) and human (Homo sapiens) cells, and it is proposed to have a quality control role in rRNA degradation [39-42]. This is a preliminary report showing the possibility of polyadenylation of ribosomal RNA in a reptilian system. On closer examination, we found a putative polyadenylation signal (AATAAA, Additional file 3) [43] sequence six bases upstream of the poly(A) tail.

Identification of toxin families

Serine proteinase

The serine proteinases in the venom gland library of S. c. edwardsii are expressed with the highest transcript abundance (38% of 360 ESTs) (Figure 1a) and belong to 19 clusters. Multiple clones appeared in 12 clusters, while 7 were singletons (Additional file 2). One representative EST from each cluster was completely sequenced (DQ464238–DQ464248, DQ439973). One of the clusters (DQ439973) contains only 3'UTR (2 ESTs). This cluster shows 90% similarity with the 3'UTR of a serine proteinase from Bothrops jararaca venom gland [44].

Most snake venom serine proteinases (SVSPs) to date are single polypeptide chains, except for two fibrinolytic enzymes from the venom of a Korean Viper, Agkistrodon blomhoffi brevicaudus (brevinase, AJ243757 and salmonase, AF176679). In both cases, a single chain precursor is most likely cleaved by proteolysis [45]. In our library, one cluster (DQ464244) shows 90% and 83% sequence identity at the nucleotide and amino acid levels respectively to salmonase. It is not clear whether or not it is also processed to form a heterodimeric serine proteinase in S. c. edwardsii venom.

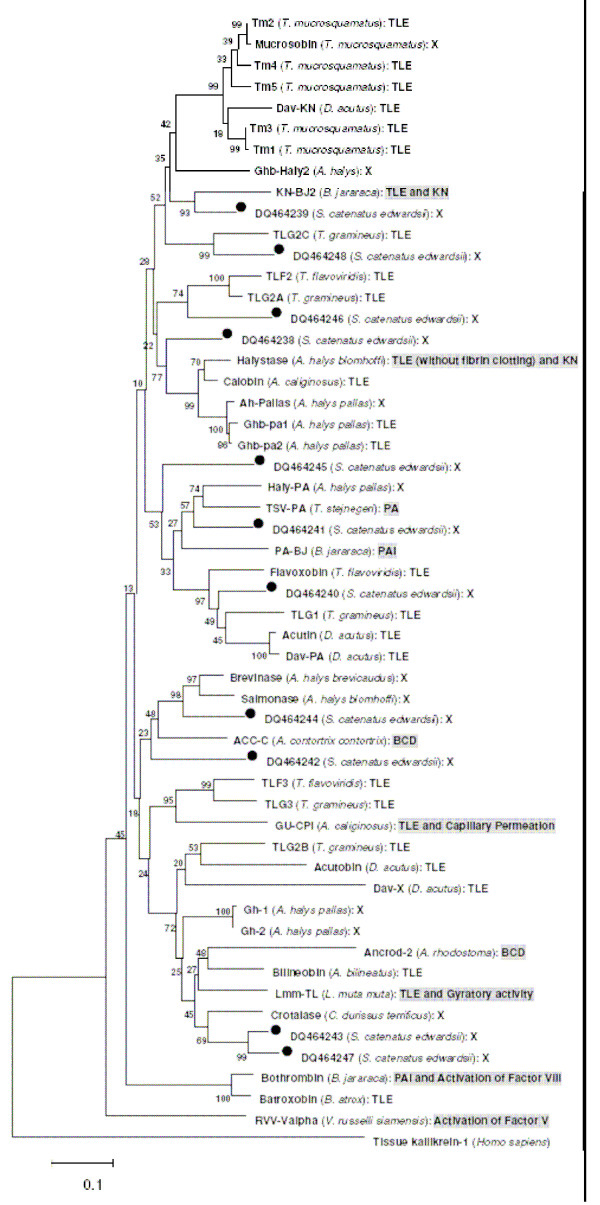

The SVSPs are found in all families of snakes and in general, they perturb the hemostatic mechanisms of prey. They act on diverse protein substrates such as fibrinogen, kininogen and platelet receptors [46,47]. Some SVSPs exhibit more than one activity. For example, in addition to their thrombin-like activity, bothrombin, crotalase and LM-TL induce platelet aggregation, kinin release and gyratory activities, respectively [48-50]. We constructed a neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree with 11 newly identified SVSP isoforms from S. c. edwardsii, to assign putative functions and to examine trends in the evolution of new isoforms [47] (Figure 2). The phylogenetic tree showed a scattered distribution of various isoforms with different pharmacological activities from several species of pitvipers. This pattern indicates that SVSPs diverged after snake lineages speciated. Many SVSPs are commonly considered as thrombin-like enzymes (TLEs) because they mimic the fibrinogenolytic function of thrombin, promoting blood coagulation. Therefore, in most cases only fibrinogenolytic function of SVSPs is tested and the SVSP is categorized as a TLE. However, some thrombin-like enzymes, in addition to releasing fibrinopeptide A and/or B from fibrinogen, also activate protein C [51], complement C3 [52] and platelets [53]. Therefore, it would be interesting to determine the specific pharmacological properties of various SVSP isoforms within each group and map these on their evolutionary relationships.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic (NJ) tree of SVSPs. Sequences (complete ORF) available from other pit vipers [47] and 11 isoforms (DQ464238–DQ464248) from this study (filled circle) were used. Tissue kallikrein-1 (P06870) is used as outgroup. The numbers on the branches indicate the bootstrap support values for nodes, and the horizontal bar represents number of substitutions per site. TLE, thrombin-like enzymes; KN, kininogenase; PA, plasminogen activator; PAI, platelet aggregation inducer; BCD, blood clot dispersion; X, activity unknown. Experimentally verified activities are shaded.

SVSP genes belong to a multigene family, and the protein-coding regions have been shown to be experiencing accelerated evolution within the venom glands of pitvipers [54]. Such accelerated evolution could lead to the changes in surface loops surrounding the substrate binding site, resulting in the variation of substrate recognition and hence, the function of the protein. The ratio between nonsynonymous and synonymous substitution (dN/dS) of the protein coding sequences of serine proteinase isoforms of this species was found to be 0.99, indicating a trend toward accelerated evolution and therefore divergence in pharmacological function during envenomation.

Metalloproteinase and Disintegrin

A total of 44 ESTs fall into 7 clusters and 7 singletons for this family of proteins (12% transcript abundance) (Figure 1a, Additional file 2). One representative EST from each cluster was sequenced (DQ464249–DQ464255). Snake venom metalloproteinase (SVMP) precursors are classified into four groups according to size and domain composition: PI (metalloproteinase domain only); PII (metalloproteinase and disintegrin domains); PIII (metalloproteinase, disintegrin and cysteine-rich domains); and PIV (PIII type domains linked to a lectin-like domain by disulfide bonds) [55]. None of the clusters encode PI type SVMPs.

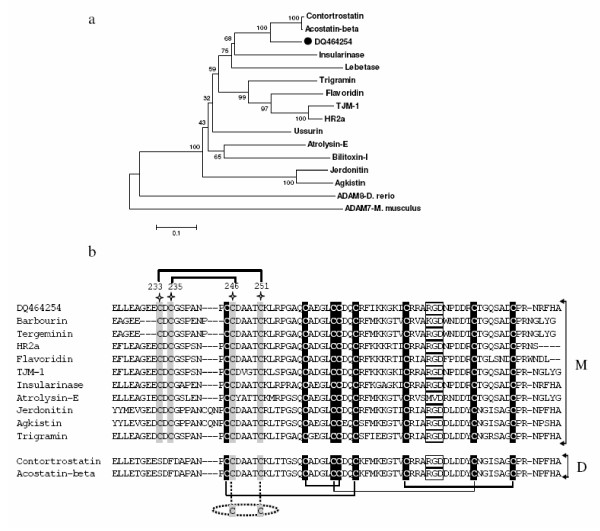

The PII isoform from S. c. edwardsii (DQ464254) matches (83–85% identity at the protein level) with the precursors of contortrostatin (Q9IAB0) and acostatin β chain (Q805F6) from A. contortrix contortrix venom. Contortrostatin and acostatin are homodimeric and heterodimeric disintegrins, respectively [56,57]. The α chain of acostatin is independently encoded and unlike other disintegrins, it is not derived by proteolytic processing [56]. However, we did not identify any ESTs matching the α chain of acostatin. Phylogenetic analysis shows that DQ464254 is closer to dimeric than monomeric disintegrins (Figure 3a). In the dimeric disintegrins, C246 and C251 form disulfide bridges with the other subunit [58,59]. However, in the monomeric disintegrins, C233 and C235 form disulfide bridges with C246 and C251, respectively, making them unavailable for dimerization (Figure 3b). Thus, characteristic Cys residues (C233 and C235) are present in all monomeric disintegrins but are absent from dimeric disintegrins [60]. The PII SVMP of S. c. edwardsii (DQ464254) contains C233 and C235 in the disintegrin domain and is likely the precursor of a monomeric disintegrin. Other monomeric disintegrins, barbourin and tergeminin, were characterized previously from the venom of S. miliarius barbouri and S. c. tergeminus, respectively [61].

Figure 3.

(a) Phylogenetic (NJ) tree for class PII metalloproteinases of viperid venoms. Dataset (complete ORF) used from [60] in addition to one isoform (DQ464254) obtained in this study (filled circle). ADAM8 from Danio rerio (Q6PFT3) and ADAM7 (from Mus musculus) were used as outgroup. (b) Alignment of the disintegrin domain of class PII SVMPs showing C233, C235, C246 and C251 (marked in grey) which are proposed to be involved in the formation of both monomeric [M] and dimeric [D] disintegrins in the venom. Only relevant portions of the sequences are shown.

The main integrin receptor binding motif of disintegrins, RGD, is found to be at the tip of a flexible hairpin loop. Variation of amino acid residues in this motif (R/K/M/W/VGD, MLD, MVD or K/RTS) on the flexible loop confers specificity towards specific receptors, e.g., replacement of R with a K in RGD motif of barbourin and ussuristatin 2 significantly increases the selectivity for αIIbβ3 (fibrinogen receptor) without affecting its binding to α5β1 (fibronectin receptor) or αvβ3 (vitronectin receptor) [62,63]. Additionally, the residues immediately adjacent to the RGD loop also influence both selectivity and affinity for integrin receptors [64,65]. For example, disintegrins with RGDW and RGDNP have selectively higher affinity for αIIbβ3 and αVβ3, respectively [63]. The RGDNP-containing disintegrins are 10-fold more potent than RGDW-containing disintegrins in blocking the adhesion of cells mediated by α5β1. The putative disintegrin from S. c. edwardsii has RGDNP, compared to RGDW and KGDW in tergeminin and barbourin, respectively. Therefore, further studies of the physiological relevance of variation in receptor selectivity among disintegrins from the same genus will be very informative.

The PIII class of SVMPs are functionally more diverse: they exhibit hemorrhagic activity, inflammatory effects, inhibition of platelet aggregation, apoptosis and prothrombin activation [66-73]. All members of the PIII class of SVMPs have six conserved Cys residues at positions 126, 166, 168, 173, 190 and 206 in their metalloproteinase domain, and some isoforms have a seventh Cys residue at three variable positions (195, 181 or 100) [60,74]. The presence of the seventh Cys residue at position 195 (subgroup PIIIa) results in proteolysis/autolysis, producing a product comprised of the disintegrin-like and cysteine-rich domains (DC domain), whereas when it is present at position 181 (subgroup PIIIb), the formation of a homodimeric structure results [60]). We have not found any isoform having a Cys residue at position 100 (103 in our alignment, Additional file 5) in our library. Two isoforms (DQ464249 and DQ464255) from S. c. edwardsii venom possess a seventh Cys residue in positions 195 and 181, and they can be grouped as PIIIa and PIIIb SVMPs, respectively (Additional file 5). Two other isoforms (DQ464250 and DQ464251) do not possess a seventh Cys residue and hence cannot be grouped with any subgroups. Some other isoforms, such as HR1a [75,76] and HF3 [68,77], also do not have the seventh Cys residue in the metalloproteinase domain. We propose that these metalloproteinases be grouped under PIII0 (suffix '0' to indicate the absence of the seventh Cys residue) (Additional data file 5). The isoform DQ464253 is a partial segment and it cannot be assigned to any subgroup. However, it shows identity with the A chain of a heterodimeric metalloproteinase identified in the venom of Vipera lebetina which induces apoptosis in endothelial cell lines [78]. Overall, the venom of S. c. edwardsii appears to have significant molecular variation among metalloproteinases and their derived components.

Phospholipase A2

Interestingly, in our cDNA library only one cluster of PLA2 (DQ464264) was found, despite having the second highest transcript abundance (28%) (Additional file 2, Figure 1a). It matches with an acidic PLA2(AAS79430) of S. c. tergeminus, with only one amino acid residue (nucleotide) difference at position 80, P(CCG) → Q(CAG), in the mature form. Thus there is no diversity of PLA2 in S. c. edwardsii venom, though snake venom PLA2 is one of the most rapidly evolving enzyme families. In most species, several isoforms of PLA2 are observed in cDNA libraries and venoms [79-81], and these have acquired diverse physiological functions [82-84]. This observation is also supported by proteomic analysis of S. c. edwardsii venom, while venoms from individuals of other species of Sistrurus contain multiple PLA2 isoforms [85].

Phosphodiesterase

Sequence of a partial singleton EST (transcript abundance 0.28%; Additional file 2, Figure 1a) (DQ464266) shows 60% identity to the C-terminal region of the phosphodiesterase gene from chimpanzee (XP_001168685). This is the first cDNA sequence for a phosphodiesterase from snake venom. Phosphodiesterase activity has been observed in venoms of Elapidae, Viperidae and Colubridae snakes [86-88]; however, the role of this enzyme in envenomation is not yet clear. Venom phosphodiesterases hydrolyze 5'-phosphodiester and pyrophosphate bonds in nucleotides and nucleic acids and release 5'-diphosphates, 5'-monophosphates and purines [89]. Free purines are also present in snake venoms, and they may contribute to envenomation sequelae [90].

L-amino acid oxidase

We obtained one cluster having 13 ESTs (transcript abundance 3.5%) (Additional file 2, Figure 1a). The complete sequence (DQ464267) shows high sequence identity (96%) with LAO of Crotalus adamanteus venom. LAOs are widely found in snake venoms and in addition to catalyzing the oxidative deamination of amino acids, they affect platelets, induce apoptosis and have hemorrhagic effects [91].

C-type lectin

In our library, CLP account for approximately 1.4% abundance and have one cluster (DQ464256) and two singletons (DQ464257 and DQ464258) (Additional file 2, Figure 1a). On BLASTP search, they match with the β subunit of mamushigin (Q9YI92; 80% identity), CHH-B (P81509; 83% identity), and the A chain of Factor IX/Factor X binding protein (IX/X-bp) (2124381A; 86% identity) respectively. Mamushigin, CHH-B and IX/X-bp are heterodimeric; however, in our library, we did not find any match to ESTs encoding the corresponding complementary subunits. Therefore, it may be interesting to examine the CLP-related proteins in this venom and determine their biological properties.

Growth factors

We obtained one cluster (transcript abundance 7%) encoding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Additional file 2, Figure 1a). Sequencing of 8 clones from this cluster showed there are two isoforms (DQ464259 and DQ464260) with only two amino acid residue (nucleotide) differences at positions 105, Q(CAG) → E(GAG), and 114, K(AAG) → E(GAG). We also sequenced a singleton (DQ464261) encoding nerve growth factor (NGF). Another singleton (DQ464277) matched with the C-terminus of connective tissue growth factor-related protein (CTGF). This is the first report of CTGF-related protein in a venom cDNA library. Its origin in the venom gland, instead of other surrounding tissues, needs to be verified.

Cysteine-rich secretory protein

We obtained one cluster (transcript abundance 7%) (Additional file 2, Figure 1a) for a CRISP (DQ464263) which matches with Catrin (AAO62995, 87% identity) from C. atrox venom. CRISPs are widely distributed in mammals, reptiles, amphibians, arthropods, nematodes, cone snails and plants, and they exhibit diverse biological functions [92]. They are single chain (MW of ~20–30 kDa), highly conserved proteins organized in three domains: a PR-1 (Pathogenesis Related proteins of group 1) domain, a hinge domain and a cysteine-rich domain (CRD). They contain 16 Cys residues forming eight conserved disulfide bonds. A few snake venom CRISPs have been shown to act upon various ion channels through the CRD domain [93-96]. However, the function of the majority of CRISPs from snake venom is unknown [97]. Therefore, it may be interesting to examine the biological properties of the CRISP found in S. c. edwardsii venom.

Bradykinin-potentiating peptide and C-type natriuretic peptide

We found a singleton (transcript abundance 0.28%; Additional file 2, Figure 1a) encoding a BPP-CNP (DQ464265) which showed 80% identity with a BPP-CNP precursor from Lachesis muta [98]. The BPP-CNP family of proteins lowers the blood pressure of prey during envenomation. Its low abundance in our library indicates that BPP-CNP may not have a significant role in envenomation by Sistrurus, unlike bites by other pitvipers (Bothrops and Lachesis) in Southern America [15,98].

Three-finger toxin like transcripts

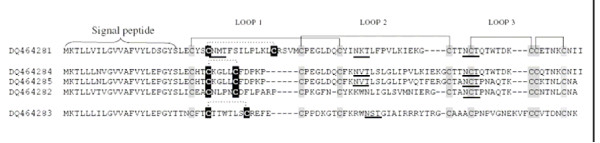

We obtained three individual singletons (Additional file 2, Figure 1a) in the library (transcript abundance 0.83%) which belong to the 3FTx family of proteins. As 3FTxs are very uncommon in viperid venoms, using targeted approach we performed RT-PCR using a separate pool of RNA as template and sequenced 96 clones. We found a total of five isoforms of 3FTx-like trancripts (DQ464281, DQ464282, DQ464283, DQ464284 and DQ464285) (Figure 4). They have a signal peptide followed by a mature protein consisting of 64–68 residues. They appear to belong to the non-conventional 3FTxs [99], with five disulfide bridges, and the fifth disulfide bridge is in loop 1 (Figure 4). All isoforms have the potential N-glycosylation motif, N-X-T/S (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of the putative precursors of 3FTxs. Cys residues which are shaded in grey are commonly present in short chain 3FTx and form 4 disulfide bridges (solid black lines). Cys residues shaded in black possibly form the additional disulfide bridge (dotted black line) present in the non-conventional 3FTx family. Potential N-glycosylation sites are underlined.

3FTxs were thought to be found only in elapid/hydrophiid venoms, though the origin of recruitment to the elapid/hydrophid venom proteome is not clear [100]. A polypeptide toxin (8 kDa) which crossreacts with α-bungarotoxin and binds with high affinity to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Kd of 7.3 × 10-10 M in competition with α-bungarotoxin) was isolated from the venom of A. halys (a pitviper) [101]. However, no sequence information of this protein is available. Recently, three clones (DY403363, DY403848 and DY403174) were obtained from a cDNA library of L. muta venom gland which potentially encode polypeptides similar to 3FTx fold proteins [98]. However, only one clone (DY403363) has the start and stop codons (complete ORF); the other two do not. These sequences do not have any homology, at either the nucleotide or protein levels, to those obtained from S. c. edwardsii (this study).

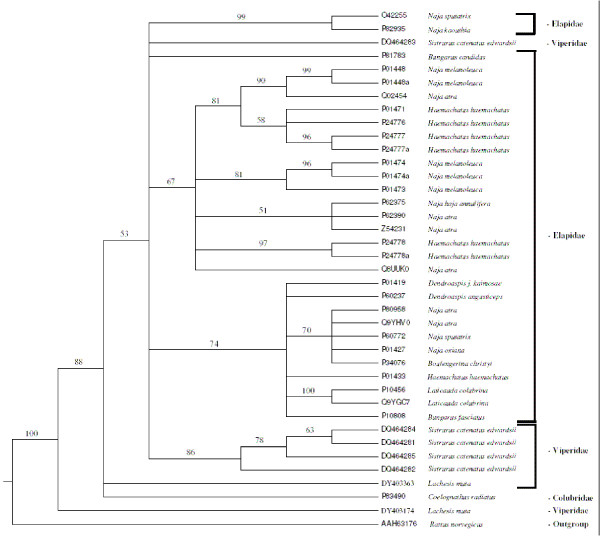

Phylogenetic analysis of 3FTXs from three families of snakes (Elapidae, Colubridae and Viperidae) was achieved using PAUP 4.10b [102]. Trees obtained using Neighbor Joining (bootstrapping) or Parsimony Analysis (strict consensus, tree is not shown) were somewhat different, but major topological features were retained (Figure 5). One transcript from S. c. edwardsii (DQ464283) does not cluster with the other four but falls within a separate clade containing Naja and Bungarus (both elapids) 3FTxs. Four other transcripts of S. c. edwardsii form a monophyletic clade within an exclusively elapid clade. Interestingly, both methods place L. muta (a viperid) clones (DY403363 and DY403174) and Coelognathus radiatus (a colubrid) 3FTx as basal to all other 3FTxs, suggesting a common origin followed by diversification of 3FTxs among all advanced snakes. Very similar trees, with the same topology of family groups, were obtained using Bayesian analyses and hence support the above conclusions (Additional file 6).

Figure 5.

Neighbor-joining cladogram of 3FTx sequences. Numbers preceeding each species name refer to Genbank accession numbers, and numbers before most nodes indicate bootstrap values (1000 replicates).

This family of proteins was not observed in a detailed proteomic characterization of S. catenatus and S. miliarius barbouri venoms [14]. cDNA libraries of other viper venom glands, including B. jararacussu, B. insularis, A. acutus and Deinagkistrodon acutus, do not show their presence [15,16,22,26]. This could be due to either low abundance transcripts and proteins or non-uniform recruitment of 3FTx into the venom proteome within Viperidae. In S. c. edwardsii, the low transcript abundance (0.83%) suggests that 3FTx are minor components of the mature venom.

In snake venoms, 3FTXs exhibit diverse pharmacological effects due to their ability to target various receptors and ion channels [103]. It is important to note that the β-sheeted loops play crucial roles in binding to various targets, and these regions are the most variable among S. c. edwardsii 3FTXs. Further, the dN/dS ratio of 0.98 (close to 1) for their coding sequences indicates that a trend towards accelerated evolution is present, as with the serine proteinases. If the variations in the β sheet loop regions are the result of positive selection (accelerated evolution), they may exhibit distinct and novel biological activities.

Novel toxin-like transcript

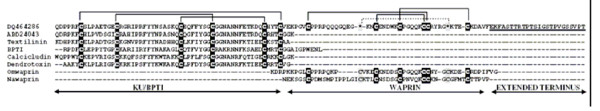

In our library, we obtained one singleton (Additional file 2, Figure 1a) (DQ464286, transcript abundance 0.28%) with an ORF encoding a signal peptide (24 residues) and a mature protein (128 residues). The putative mature protein is rich in Cys residues, similar to many other snake venom toxins. Its N-terminal domain matches with Kunitz/BPTI toxins (53–68% identity) and the middle domain matches with waprins (45–58% identity), and the novel transcript has an extended C-terminus (Figure 6). Both Kunitz/BPTI [104] and waprins [105,106] are found separately as single domain proteins in snake venoms. Two of the Cys residues, which form one of the four disulfide bonds in waprins, are missing in the new transcript (Figure 6). RT-PCR using a fresh RNA (other than used to make cDNA library) as template and sequencing experiments show the presence of this fused transcript in the venom gland and hence it is not an artifact due to template switching by the Reverse Transcriptase used for making the cDNA library [107-109]. Although a number of cDNA sequences of Kunitz/BPTI from snake venoms have been completed, none of them have the waprin domain and the C-terminal extension. Currently, cDNA sequences of waprins are not known. However, this is the first experimental evidence for the presence of a waprin domain (though fused with another toxin) in viperid venom.

Figure 6.

Alignment of the novel toxin-like transcript with snake venom Kunitz/BPTI proteins and waprins. ABD24043 (Daboia russellii russellii); Q90W98 (Textilinin, Pseudonaja textilis textilis); P81658 (Calcicludin, Dendroaspis angusticeps); P00981 (Dendrotoxin-K, Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis) and BPTI from Bovine. P83952 (Omwaprin, Oxyuranus microlepidotus); P60589 (Nawaprin, Naja nigricollis). The presence of conserved disulfide bonds are indicated by solid black lines. The disulfide bond which is missing in the novel toxin but conserved in waprins is indicated by dotted lines. The extended C-terminus of the novel toxin is underlined.

The longer ORF having Kunitz/BPTI and waprin domains together could be due to the fusion of two individual genes encoding Kunitz/BPTI and waprin. Gene fusion mediated by exon shuffling (intron mediated recombination or retrotransposition) has been established as an essential genetic mechanism for the origin of new genes in invertebrates, vertebrates and plants [110,111]. Recently, a new genetic process, transcription-induced chimerism (TIC), in cases of tandemly located gene pairs has been shown to be responsible for gene fusion in the human genome, producing chimeric proteins [112,113]. It is not clear at this stage how this novel fused gene has originated in the snake venom gland. This fused transcript may code either for a precursor which is processed to form two individual classes of venom proteins (Kunitz/BPTI and waprin) or a novel toxin with two distinct domains and having a new biological function. It has been observed that new genes often give rise to new biological functions driven by adaptive Darwinian selection [114-116]. The mechanism of fusion of these apparently independent genes, the evolutionary trajectory of this fused gene and the potential new toxic function of the chimeric protein are all areas for future investigation.

Iron-binding protein

Four ESTs (Additional file 2, Figure 1a) (dbEST: SCEHYPO1, transcript abundance 1.11%) showed homology with an iron-binding protein with a potential signal peptide. Although most iron-binding proteins are generally categorized as storage protein, some of them, such as ovotransferrin and lactoferrin, have antimicrobial activities [117-119]. It is not clear whether or not this protein is found in the venom. However, omwaprin, a member of the waprin protein family, and the C-terminal region of a myotoxic PLA2 were both shown to have antimicrobial activity [105,120].

Identification of cellular transcripts

We obtained 106 clusters (transcript abundance 21%, 107 sequences) which are involved in various cellular functions, including transcription and translation, secretion, post-translational modification, general metabolism and other functions (Additional file 3, Figure 1b). Similar house-keeping protein products have been observed in other snake venom glands [13,15,22]. One of the ESTs (SCE438) matches (74%) a calcium- and integrin-binding protein which assists platelet spreading [121]. Although modulation of platelet and integrin functions is a key activity of several snake venom components, we do not believe that this protein is present in venom, as it lacks the signal peptide.

Overall, results from our cDNA library demonstrate extensive molecular diversity in the venom composition of S. c. edwardsii. Serine proteinase and metalloproteinase isoforms are the most abundant components and in the venom, they exert diverse pharmacological activities, particularly disrupting hemostasis. The numerous minor components likely play an ancillary role in envenomation. These diverse toxin isoforms, together with minor components, may be characteristic of venoms from species utilizing different prey types, such as lizards (ectotherms) and birds and mammals (endotherms) [122].

Venom composition and genetics of their origin

Snake venoms consist of a diverse range of pharmacologically active protein and peptide toxins which are primarily used in prey capture and secondarily as defense weapons. To date, the majority of the work on toxin identification and characterization has been concentrated on snakes of the families Elapidae and Viperidae because they are often abundant, produce high yields of venom and represent a significant risk to human health worldwide. Recent studies of venom transcriptomes and proteomes indicate that our knowledge of venom composition is partly limited by experimental detectability. For example, 3FTxs, which were thought to be found exclusively in elapid venoms, were detected in viperid venom gland transcriptomes only recently [[98] and in this study]. Similarly, CLP, thought to be limited to viperid venoms, have been detected recently in the venom gland of Philodryas olfersii (Colubridae) and Bungarus species (Elapidae) [27,106,123,124]. Further, a new family of low abundance toxin (vespryns) was identified in both elapid and viperid venoms [98,123], Therefore, with the application of advanced techniques like EST sequencing, "compositional specificities" between families of venomous snakes may become less distinct (Additional file 1). Multiple recruitment events may lead to an increase in the spectrum of known and unknown toxin families, decreasing the compositional specificities among venomous snakes. However, differential contribution of specific toxins to the overall expressed proteome of venomous snakes does lead to significant differences in venom composition between species.

A central theme in the evolution of venom systems is complete duplication of toxin genes, followed by accelerated evolution which favors nonsynonymous amino acid substitution towards neofunctionalization. Modification of selected surface areas of toxins [82] is responsible for producing the functional diversity in animal (invertebrates: snails and scorpions; vertebrates: snakes) toxin multigene families [125]. However, one important observation in the present report is the occurrence of a novel toxin-like transcript generated by fusion of two individual toxin genes, Kunitz/BPTI and waprin, in a snake venom gland. Though the mechanism for creation of this fused gene needs to be studied further, it clearly indicates that other genetic processes (gene shuffling or TIC) are also operating in the venom gland to create novel toxin genes. Genes originating by other genetic processes such as exon shuffling are recent [111], and therefore the addition of this fused toxin-like transcript to the venom proteome is perhaps new. At this stage, it is tempting to speculate that the origin of modular organization of different classes of SVMPs, which appears to be the result of gene fusion events, may be due to a genetic process other than gene duplication. SVMPs are very abundant toxins and carry out a principal role in envenomation by viperid snakes, and therefore studies of their genetic origin and organization will be of great interest. Circumstantial evidence of trans-splicing for the generation of serine proteinase isoforms in the venom gland of V. lebetina has been presented [126]. Kopelman et al.[127] have shown that alternative splicing and gene duplication are inversely correlated evolutionary mechanisms. According to Parra et al. [113], only 4–5% of the tandem gene pairs in the human genome can produce chimeric proteins. It is obvious that these alternative genetic processes responsible for expanding functional proteomes are uncommon among biological systems, and it is therefore not surprising in our case to have just a singleton of the fused transcript out of 576 ESTs (transcript abundance 0.28%). This also demonstrates that to detect rare genetic processes operating in the venom gland, the library generated must be of high quality and that subsequent analyses must be performed very carefully. In turn, these analyses help elucidate in detail the principles of evolution of snake venom transcriptome which have led to the evolutionary success of the advanced snakes [128].

Conclusion

The composition of snake venoms has been shown to be dependent on numerous factors, including phylogeny, diet, age, geography and even sex [129-132]. In general, greater similarity of venoms will be observed along broad phylogenetic lines (e.g., within-family than between-family). However, as this study has demonstrated, some toxins classically considered to occur in only one family, such as the 3FTxs, are actually broadly distributed among the advanced snakes (Colubroidea). The present capacity to detect low abundance toxins indicates a greater compositional similarity of venoms among advanced snakes than has been previously recognized. Further, we have demonstrated that in addition to gene duplication, exon shuffling or transcriptional splicing may also contribute to generating the diversity of toxins and toxin isoforms observed among snake venoms. Overall, the elucidation of the venom gland transcriptome of S. c. edwardsii contributes to a broader picture of toxin expression which complements and extends proteomic analysis of this venom [85]. These approaches can lead to the identification of new toxins and provides mechanistic explanations for their evolution and diversification. An unresolved question involves the relationship between the venom gland transcriptome and how this is ultimately translated to the final proteome. This variable proteomic composition in turn determines the complex and often difficult to resolve sequelae which frequently develop following envenomation by the different species of venomous snakes.

Methods

Venom extraction and collection of venom glands

Specimens of Sistrurus c. edwardsii (Desert Massasauga) were collected in Lincoln County, Colorado, USA under permits granted by the Colorado Division of Wildlife to SPM (permits #0456, 06HP456). Venom was extracted from adult snakes using standard manual methods [133]; venoms were then centrifuged to remove particulates, frozen and lyophilized. Prior to gland removal, snakes were extracted of venom. Four days later, when mRNA levels are presumed maximal [134], two snakes were anesthetized with isofluorane and then sacrificed by decapitation. Glands were then rapidly dissected from the snakes, cut into small pieces and placed in approximately 0.5 mL RNAlater (Qiagen) and frozen at -80°C until used.

cDNA library construction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from a single venom gland using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The integrity of total RNA was confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis. The mRNA was purified using an mRNA isolation kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). The purified total mRNA was used to make the cDNA library following the instructions of the SMART cDNA library construction kit (Vector used: λ TriplEx2) (Clontech, Mountain view, California, USA). Small size and incomplete cDNAs were removed by passing the library through CHROMA SPIN-400column. The library was packaged using Gigapack gold packaging extract (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, Texas, USA). Individual clones were rescued from randomly selected white plaques and grown in Luria broth + ampicillin medium. Plasmids were purified using the QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Purified plasmids were sequenced by cycle sequencing reactions using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 kit (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, California, USA) and an automated DNA sequencer (Model 3100A, Applied Biosystem, Foster City, California, USA).

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was performed in order to search for isoforms of 3FTx sequences in the venom gland. In brief, total RNA was isolated from venom glands as above and was used as template. The following primers were used for amplification: forward primer, 5' ATGAAAACTCTGCTGNTGATCCTGGNG 3' (N = A/C/G/T); reverse primer, 5' GGTTTATGGACCATCCTGTGGTAAAGGC 3'. Reverse transcription and subsequent amplification reactions were done using the one step RT-PCR protocol of Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). The amplified product was cloned into pDrive vector (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and 96 random clones were sequenced. RT-PCR was also performed to confirm the presence of fused toxin transcript in the venom using same procedure with the following primers: forward primer, 5' ATGTCTTCTGGAGGTCTTCTGCTG 3'; reverse primer, 5' TCCAG GACAGAAGAAGGCTCTGAT 3'.

Bioinformatic analysis

Clustering of the ESTs was performed using the CAP3 program [135] after removing poor quality sequences and vector sequences using VecScreen from NCBI. We looked for Sfi I (A & B) recognition sequences in the ESTs and manually removed upstream and downstream sequences of these sites as well as poly(A) tails (at least 10 A's in a row) from the 3' ends. A minimum overlap of 50 bp and 100% identity in the overlap region were selected as criteria for the clustering. All clusters and singletons were subjected to BLAST searches (BLASTN and BLASTX as required) against the non-redundant database of NCBI (e-values cutoff < 10-5 and having a good coverage of minimum 100 base pairs and >98% identity) for the putative identification of the genes [136]. Presence of signal peptides was predicted individually by submission of the sequences to the SignalP server as available in the Expasy website. Gene and protein alignments were done using the programs ClustalW and DNAMAN (Lynnon Corporation, Vaudreuil-Dorion, Quebec, Canada). The ratio between nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous substitution (dS) were calculated using the SNAP program [137]. The program SNAP has been developed based on the method of [138] with incorporation of statistical analysis developed by [139].

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using the program MEGA version 3.1[140], using Poisson-corrected distances, and trees were constructed applying bootstraps of 1000 replicates. PAUP 4.0b10 [102] was also used for Bootstrap, Neighbor Joining and Parsimony analyses. For the Bayesian inferences of phylogeny (based upon the posterior probability distribution of the trees: Markov chain Monte Carlo methods), MrBayes v3.1.2 [141] was used. The analysis was run for 5 × 106 generations in four chains and sampled every 100 generations, resulting in 50,000 sample trees. The log-likelihood score of each saved tree was plotted against the number of generations to determine the point at which the log-likelihood scores of the analysis reached the asymptote. The posterior probabilities for the clades were established by constructing a consensus tree of all trees generated after the completion of the burn-in phase.

We included the following sequences from three families of snakes in our analyses: the newly identified 3FTx sequences out of this study from S. c. edwardsii (Viperidae) [GenBank: DQ464281, DQ464282, DQ464283, DQ464284 and DQ464285]; L. muta (Viperidae) [GenBank: DY403363, DY403174], α-colubritoxin [Swiss-Prot: P83490] from Coelognathus radiatus (Colubridae), and non-conventional 3FTx sequences [Swiss-Prot: P81783, O42255 and P82935], 3FTx-like sequences [Swiss-Prot: Q02454, P62375, P24778, P24777, P24776, P01471, P62390, P01473, 229475, P01448, P01474, Q8UUK0 and Z54231] [142] and 3TFx sequences [Swiss-Prot: P10808, P01433, P01427, Q9YGC7, P10456, Q9YHV0, P80958, P60772, P34076, P01419 and P60237] from Elapidae. All these sequences belong to the short chain 3FTx family. A BLASTP search using [GenBank: DY403174] from L. muta venom found that a rat peptide sequence [GenBank: AAH63176] showed the highest homology to Ly6 antigen, which has been proposed to be a potential ancestor of snake venom 3FTxs [100,143], and this peptide was used as outgroup in our analysis.

Accession numbers

Nucleotide sequence data reported here have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers [GenBank: DQ464238–DQ464286]. ESTs are deposited in dbEST with accession numbers [dbEST: DY587747–DY588245 and DY625701–DY625710].

List of abbreviations

EST, expressed sequence tag; ORF, open reading frame; PLA2, phospholipase A2; 3FTx, three-finger toxin; CRISP, cysteine-rich secretory protein; CLP, C-type lectins; BPP, bradykinin-potentiating peptides; CNP, C-type natriuretic peptides; LAO, L-amino acid oxidase; BPTI, bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factors; NGF, nerve growth factor; SVSP, snake venom serine proteinases; TLE, thrombin-like enzymes; CRD, cysteine-rich domain; NJ, neighbor-joining; TIC, transcription-induced chimerism.

Authors' contributions

SP has designed and carried out experiments, analysed data, developed the concept and wrote the manuscript. SPM has collected the venom gland sample. RMK and SPM have edited the manuscript to improve its quality. SPM has helped in the phylogenetic analysis of 3FTxs sequences. All the authors have approved the final form of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

It is a table showing the distribution of snake venom toxin families among Superfamily Colubroidae.

It is a table showing the clusters of ESTs, number of clones in each cluster and their putative identity.

It is a table showing the clusters of ESTs encoding cellular proteins.

ClustalW alignment between 12S ribosomal RNA sequence DQ464268 (from this study) and AF057227 (used for taxonomic identification of S. c. edwardsii). Polyadenylation signal sequence is underlined.

ClustalW alignment of PIII metalloproteinases (only proteinase domain is shown). Cysteine residues which are conserved are marked in grey and variable in black. Accession numbers of the used sequences are as follows: VAP1 [GenBank: BAB18307], HV1 [GenBank: BAB60682], Halysase [GenBank: 27465044], VLAIP-A [GenBank: 61104775], VLAIP-B [GenBank: 61104777], Kaouthiagin [Swiss-Prot: P82942], Berythractivase [Swiss-Prot: Q8UVG0], Ecarin [Swiss-Prot: Q90495], Jararhagin [Swiss-Prot: P30431], Bothropasin [Swiss-Prot: O93523], Acurhagin [Swiss-Prot: Q6Q274], Catrocollastatin [Swiss-Prot: Q90282], Atrolysin [Swiss-Prot: Q92043], Stejnihagin-A [Swiss-Prot: Q3HTN1], Stejnihagin-B [Swiss-Prot: Q3HTN2], HR1A [Swiss-Prot: Q8JIR2], HR1B [Swiss-Prot: P20164], HF3 [GenBank: 31742525]. P, signal peptide domain; PRO, pro-domain; S, spacer; DISIN, disintegrin domain; CRD, cysteine-rich domain

Bayesian tree generated from 39 aligned 3FTx sequences as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers on branches indicate percentage of posterior clade probability. 3FTx sequences from S. c. edwardsii and L. muta libraries are marked with a filled circle and triangle respectively.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported from the grants from Biomedical Research Council, Agency for Science and Technology Research, Singapore (RMK). Permits and support for collection of snakes was provided by the Colorado Division of Wildlife (06HP456, SPM). The assistance of W.H. Heyborne and Susan J Moore with some aspects of phylogenetic analyses was greatly appreciated.

Contributor Information

Susanta Pahari, Email: susanta2001@yahoo.com.

Stephen P Mackessy, Email: Stephen.Mackessy@unco.edu.

R Manjunatha Kini, Email: dbskinim@nus.edu.sg.

References

- Vidal N. Colubroid systematics: Evidence for an early appearance of the venom apparatus followed by extensive evolutionary tinkering. J Toxicol Toxin Rev. 2002;21:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mackessy SP. Biochemistry and pharmacology of colubrid snake venoms. J Toxicol Toxin Rev. 2002;21:43–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal N, Hedges SB. Higher-level relationships of snakes inferred from four nuclear and mitochondrial genes. C R Biol. 2002;325:977–985. doi: 10.1016/S1631-0691(02)01510-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry BG, Wuster W. Assembling an arsenal: origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:870–883. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson WC, Wickramaratna JC. In vitro neuromuscular activity of snake venoms. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:807–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J, Stocker K. Effects of snake venoms on hemostasis. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1991;21:171–182. doi: 10.3109/10408449109089878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braud S, Bon C, Wisner A. Snake venom proteins acting on hemostasis. Biochimie. 2000;82:851–859. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(00)01178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Fujimura Y, Titani K. Snake venom proteases affecting hemostasis and thrombosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:146–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita T. C-type lectin-related proteins from snake venoms. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2004;4:357–373. doi: 10.2174/1568006043335916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloog Y, Ambar I, Sokolovsky M, Kochva E, Wollberg Z, Bdolah A. Sarafotoxin, a novel vasoconstrictor peptide: phosphoinositide hydrolysis in rat heart and brain. Science. 1988;242:268–270. doi: 10.1126/science.2845579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazaa A, Marrakchi N, El Ayeb M, Sanz L, Calvete JJ. Snake venomics: comparative analysis of the venom proteomes of the Tunisian snakes Cerastes cerastes, Cerastes vipera and Macrovipera lebetina. Proteomics. 2005;5:4223–4235. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200402024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell GW, Earl S, Masci PP, de Jersey J, Wallis TP, Gorman JJ, Lavin MF. Molecular diversity in venom from the Australian Brown Snake, Pseudonaja textilis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:379–389. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500270-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti IM, My-Pham V, Harrison J, Garfield MK, Ribeiro JM. Bitis gabonica (Gaboon viper) snake venom gland: toward a catalog for the full-length transcripts (cDNA) and proteins. Gene. 2004;337:55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez P, Sanz L, Calvete JJ. Snake venomics: characterization of protein families in Sistrurus barbouri venom by cysteine mapping, N-terminal sequencing, and tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Proteomics. 2004;4:327–338. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL, Ho PL. A survey of gene expression and diversity in the venom glands of the pitviper snake Bothrops insularis through the generation of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) Gene. 2002;299:279–291. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima S, Roberto PG, Soares AM, Astolfi-Filho S, Pereira JO, Giuliati S, Faria M, Jr., Xavier MA, Fontes MR, Giglio JR, Franca SC. Analysis of Bothrops jararacussu venomous gland transcriptome focusing on structural and functional aspects: I--gene expression profile of highly expressed phospholipases A2. Biochimie. 2004;86:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Fry BG, Kini RM. Eggs-only diet: its implications for the toxin profile changes and ecology of the marbled sea snake (Aipysurus eydouxii) J Mol Evol. 2005;60:81–89. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Fry BG, Kini RM. Putting the brakes on snake venom evolution: the unique molecular evolutionary patterns of Aipysurus eydouxii (Marbled sea snake) phospholipase A2 toxins. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:934–941. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Wang J, Zhang X, Ren Y, Wang N, Zhao K, Chen X, Zhao C, Li X, Shao J, Yin J, West MB, Xu N, Liu S. Proteomic characterization of two snake venoms: Naja naja atra and Agkistrodon halys. Biochem J. 2004;384:119–127. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawarak J, Sinchaikul S, Wu CY, Liau MY, Phutrakul S, Chen ST. Proteomics of snake venoms from Elapidae and Viperidae families by multidimensional chromatographic methods. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:2838–2854. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre LS, Woods R, Earl S, Masci PP, Lavin MF. Identification and analysis of venom gland-specific genes from the coastal taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) and related species. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2679–2693. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5384-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qinghua L, Xiaowei Z, Wei Y, Chenji L, Yijun H, Pengxin Q, Xingwen S, Songnian H, Guangmei Y. A catalog for transcripts in the venom gland of the Agkistrodon acutus: identification of the toxins potentially involved in coagulopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano SM, Shannon JD, Wang D, Camargo AC, Fox JW. A multifaceted analysis of viperid snake venoms by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis: an approach to understanding venom proteomics. Proteomics. 2005;5:501–510. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai IH, Chen YH, Wang YM. Comparative proteomics and subtyping of venom phospholipases A2 and disintegrins of Protobothrops pit vipers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1702:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff SC, Harrison RA. Venom gland EST analysis of the saw-scaled viper, Echis ocellatus, reveals novel alpha9beta1 integrin-binding motifs in venom metalloproteinases and a new group of putative toxins, renin-like aspartic proteases. Gene. 2006;377:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Liu Q, Yin W, Zhang X, Huang Y, Luo Y, Qiu P, Su X, Yu J, Hu S, Yan G. Transcriptome analysis of Deinagkistrodon acutus venomous gland focusing on cellular structure and functional aspects using expressed sequence tags. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching AT, Rocha MM, Paes Leme AF, Pimenta DC, de Fatima DF, Serrano SM, Ho PL, Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL. Some aspects of the venom proteome of the Colubridae snake Philodryas olfersii revealed from a Duvernoy's (venom) gland transcriptome. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4417–4422. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidade DA, Simao TA, Davila AM, Wagner G, de LMJ, Lee HP, Bon C, Zingali RB, Albano RM. Bothrops jararaca venom gland transcriptome: Analysis of the gene expression pattern. Toxicon. 2006;48:437–461. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackessy SP. Desert Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii): a technical conservation assessment. 2005. p. 57.http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/massasauga.pdf

- Stebbins RC. In: A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians. 2nd. Mifflin H, editor. New York; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt WG, Painter CW, Price AH. The Amphibians and Reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hobert JP, Montgomery CE, Mackessy SP. Natural History of the Massasauga Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii, in Southeastern Colorado. The Southwestern Naturalist. 2004;49:321–326. doi: 10.1894/0038-4909(2004)049<0321:NHOTMS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holycross AT, Mackessy SP. Variation in the diet of Sistrurus catenatus (Massasauga), with emphasis on Sistrurus catenatus edwardsii (Desert Massasauga) Journal of Herpetology. 2002;36:454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Allen WB., JR. State lists of endangered and threatened species of reptiles and amphibians and laws and regulations covering collecting of reptiles and amphibians in each state. Chicago, Illinois, Chicago Herpetological Society; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Seigel AR. Ecology and conservation of an endangered rattlesnake, Sistrurus catenatus, in Missouri, USA. Biological Conservation. 1986;35:333–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(86)90093-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wuster W, Golay P, Warrell DA. Synopsis of recent developments in venomous snake systematics, No. 3. Toxicon. 1999;37:1123–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(98)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pook CE, McEwing R. Mitochondrial DNA sequences from dried snake venom: a DNA barcoding approach to the identification of venom samples. Toxicon. 2005;46:711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson CL. Molecular systematics and biogeographical history of pitvipers as determined by mitochondrial ribosomal DNA sequences. Copeia. 1999;3:576–586. doi: 10.2307/1447591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decuypere S, Vandesompele J, Yardley V, De Donckeri S, Laurent T, Rijal S, Llanos-Cuentas A, Chappuis F, Arevalo J, Dujardin JC. Differential polyadenylation of ribosomal RNA during post-transcriptional processing in Leishmania. Parasitology. 2005;131:321–329. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005007808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann J, Liu H, Wu CP. Polyadenylation of ribosomal RNA by Candida albicans also involves the small subunit. BMC Mol Biol. 2004;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuai L, Fang F, Butler JS, Sherman F. Polyadenylation of rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8581–8586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402888101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomovic S, Laufer D, Geiger D, Schuster G. Polyadenylation and degradation of human mitochondrial RNA: the prokaryotic past leaves its mark. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6427–6435. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6427-6435.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E, Kuhn U. The mechanism of 3' cleavage and polyadenylation of eukaryotic pre-mRNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1997;57:41–71. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saguchi K, Hagiwara-Saguchi Y, Murayama N, Ohi H, Fujita Y, Camargo AC, Serrano SM, Higuchi S. Molecular cloning of serine proteinases from Bothrops jararaca venom gland. Toxicon. 2005;46:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Seu JH, Rhee IK, Jin I, Kawamura Y, Park W. Purification and characterization of brevinase, a heterogeneous two-chain fibrinolytic enzyme from the venom of Korean snake, Agkistrodon blomhoffii brevicaudus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:665–670. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano SM, Maroun RC. Snake venom serine proteinases: sequence homology vs. substrate specificity, a paradox to be solved. Toxicon. 2005;45:1115–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Wang SR, Tsai IH. Serine protease isoforms of Deinagkistrodon acutus venom: cloning, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. Biochem J. 2001;354:161–168. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markland FS, Kettner C, Schiffman S, Shaw E, Bajwa SS, Reddy KN, Kirakossian H, Patkos GB, Theodor I, Pirkle H. Kallikrein-like activity of crotalase, a snake venom enzyme that clots fibrinogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:1688–1692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S, Fujimura Y, Miura S, Ozaki Y, Usami Y, Suzuki M, Titani K, Yoshida E, Sugimoto M, Yoshioka A, . Purification and characterization of bothrombin, a fibrinogen-clotting serine protease from the venom of Bothrops jararaca. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1843–1849. doi: 10.1021/bi00173a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira AM, Magalhaes A, Diniz CR, de Oliveira EB. Purification and properties of the thrombin-like enzyme from the venom of Lachesis muta muta. Int J Biochem. 1989;21:863–871. doi: 10.1016/0020-711X(89)90285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel W, Kondo S, Smith KJ, McMullen BA, Smith LF. Characterization of a protein C activator from Agkistrodon contortrix contortrix venom. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12607–12613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C, Tsuru D, Oda-Ueda N, Ohno M, Hattori S, Kim ST. Flavoxobin, a serine protease from Trimeresurus flavoviridis (habu snake) venom, independently cleaves Arg726-Ser727 of human C3 and acts as a novel, heterologous C3 convertase. Immunology. 2002;107:111–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewiarowski S, Kirby EP, Brudzynski TM, Stocker K. Thrombocytin, a serine protease from Bothrops atrox venom. 2. Interaction with platelets and plasma-clotting factors. Biochemistry. 1979;18:3570–3577. doi: 10.1021/bi00583a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshimaru M, Ogawa T, Nakashima K, Nobuhisa I, Chijiwa T, Shimohigashi Y, Fukumaki Y, Niwa M, Yamashina I, Hattori S, Ohno M. Accelerated evolution of crotalinae snake venom gland serine proteases. FEBS Lett. 1996;397:83–88. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hite LA, Jia LG, Bjarnason JB, Fox JW. cDNA sequences for four snake venom metalloproteinases: structure, classification, and their relationship to mammalian reproductive proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;308:182–191. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda D, Koike H, Morita T. A new gene structure of the disintegrin family: a subunit of dimeric disintegrin has a short coding region. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14248–14254. doi: 10.1021/bi025876s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Nakada MT, Brooks PC, Swenson SD, Ritter MR, Argounova S, Arnold C, Markland FS. Contortrostatin, a homodimeric disintegrin, binds to integrin alphavbeta5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:350–355. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete JJ, Jurgens M, Marcinkiewicz C, Romero A, Schrader M, Niewiarowski S. Disulphide-bond pattern and molecular modelling of the dimeric disintegrin EMF-10, a potent and selective integrin alpha5beta1 antagonist from Eristocophis macmahoni venom. Biochem J. 2000;345 Pt 3:573–581. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3450573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete JJ, Moreno-Murciano MP, Theakston RD, Kisiel DG, Marcinkiewicz C. Snake venom disintegrins: novel dimeric disintegrins and structural diversification by disulphide bond engineering. Biochem J. 2003;372:725–734. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JW, Serrano SM. Structural considerations of the snake venom metalloproteinases, key members of the M12 reprolysin family of metalloproteinases. Toxicon. 2005;45:969–985. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough RM, Rose JW, Hsu MA, Phillips DR, Fried VA, Campbell AM, Nannizzi L, Charo IF. Barbourin. A GPIIb-IIIa-specific integrin antagonist from the venom of Sistrurus m. barbouri. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9359–9362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshikawa K, Terada S. Ussuristatin 2, a novel KGD-bearing disintegrin from Agkistrodon ussuriensis venom. J Biochem. 1999;125:31–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough RM, Rose JW, Naughton MA, Phillips DR, Nannizzi L, Arfsten A, Campbell AM, Charo IF. Characterization of the integrin specificities of disintegrins isolated from American pit viper venoms. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1058–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aota S, Nagai T, Yamada KM. Characterization of regions of fibronectin besides the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid sequence required for adhesive function of the cell-binding domain using site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15938–15943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins. Science. 1987;238:491–497. doi: 10.1126/science.2821619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Kini RM, Gopalakrishnakone P. A novel prothrombin activator from the venom of Micropechis ikaheka: isolation and characterization. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;408:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason JB, Fox JW. Hemorrhagic metalloproteinases from snake venoms. Pharmacol Ther. 1994;62:325–372. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa EP, Clissa PB, Teixeira CF, Moura-da-Silva AM. Importance of metalloproteinases and macrophages in viper snake envenomation-induced local inflammation. Inflammation. 2002;26:13–17. doi: 10.1023/A:1014465611487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing GD, Moura-da-Silva AM. Jararhagin and its multiple effects on hemostasis. Toxicon. 2005;45:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WJ, Shih CH, Huang TF. Primary structure and antiplatelet mechanism of a snake venom metalloproteinase, acurhagin, from Agkistrodon acutus venom. Biochimie. 2005;87:1065–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Ohta T, Kaji K, Fox JW, Hayashi H, Araki S. cDNA cloning and characterization of vascular apoptosis-inducing protein 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:197–204. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You WK, Seo HJ, Chung KH, Kim DS. A novel metalloprotease from Gloydius halys venom induces endothelial cell apoptosis through its protease and disintegrin-like domains. J Biochem. 2003;134:739–749. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loria GD, Rucavado A, Kamiguti AS, Theakston RD, Fox JW, Alape A, Gutierrez JM. Characterization of 'basparin A,' a prothrombin-activating metalloproteinase, from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper that inhibits platelet aggregation and induces defibrination and thrombosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;418:13–24. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan SG, Jin Y, Lee WH, Zhang Y. Cloning of two novel P-III class metalloproteinases from Trimeresurus stejnegeri venom gland. Toxicon. 2006;47:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori-Satoh T, Ohsaka A. Purification and some properties of hemorrhagic principle I in the venom of Trimeresurus flavoviridis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;207:432–444. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2795(70)80006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori-Satoh T, Sadahiro S. Resolution of the major hemorrhagic component of Trimeresurus flavoviridis venom into two parts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;580:392–404. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(79)90151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva CA, Zuliani JP, Assakura MT, Mentele R, Camargo AC, Teixeira CF, Serrano SM. Activation of alpha(M)beta(2)-mediated phagocytosis by HF3, a P-III class metalloproteinase isolated from the venom of Bothrops jararaca. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:950–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trummal K, Tonismagi K, Siigur E, Aaspollu A, Lopp A, Sillat T, Saat R, Kasak L, Tammiste I, Kogerman P, Kalkkinen N, Siigur J. A novel metalloprotease from Vipera lebetina venom induces human endothelial cell apoptosis. Toxicon. 2005;46:46–61. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SB, Armugam A, Kini RM, Jeyaseelan K. Phospholipase A(2) with platelet aggregation inhibitor activity from Austrelaps superbus venom: protein purification and cDNA cloning. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;375:289–303. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai IH, Wang YM, Chen YH, Tsai TS, Tu MC. Venom phospholipases A2 of bamboo viper (Trimeresurus stejnegeri): molecular characterization, geographic variations and evidence of multiple ancestries. Biochem J. 2004;377:215–223. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath BS, Kini RM, Gowda TV. Characterization of three edema-inducing phospholipase A2 enzymes from habu (Trimeresurus flavoviridis) venom and their interaction with the alkaloid aristolochic acid. Toxicon. 1987;25:501–515. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(87)90286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kini RM, Chan YM. Accelerated evolution and molecular surface of venom phospholipase A2 enzymes. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:125–132. doi: 10.1007/PL00006450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch VJ. Inventing an arsenal: adaptive evolution and neofunctionalization of snake venom phospholipase A2 genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Nakashima K, Nobuhisa I, Deshimaru M, Shimohigashi Y, Fukumaki Y, Sakaki Y, Hattori S, Ohno M. Accelerated evolution of snake venom phospholipase A2 isozymes for acquisition of diverse physiological functions. Toxicon. 1996;34:1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(96)00112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz L, Gibbs HL, Mackessy SP, Calvete JJ. Venom proteomes of closely related Sistrurus rattlesnakes with divergent diets. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2098–2112. doi: 10.1021/pr0602500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman HG, Kaletta U. Identity of the phosphodiesterase and deoxyribonuclease in rattle-snake venom. Nature. 1956;178:1394–1395. doi: 10.1038/1781394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackessy SP. Phosphodiesterases, DNases and RNases. Bailey, G.S. (Ed.) Ft. Collins, CO, USA., Alaken Press, Inc.,; 1998. pp. 361–404. (In: Enzymes from Snake Venoms). [Google Scholar]

- Russell FE. Phosphodiesterase of some snake and arthropod venoms. Toxicon. 1966;4:153–154. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(66)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenau CR, Trentin DS, Barreto-Chaves ML, Sarkis JJ. Ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase as part of a multiple system for nucleotide hydrolysis by platelets from rats: kinetic characterization and biochemical properties. Platelets. 2006;17:84–91. doi: 10.1080/09537100500246641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird SD. Ophidian envenomation strategies and the role of purines. Toxicon. 2002;40:335–393. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00232-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan NH. Enzymes from Snake Venoms. In: Bailey, G.S. (Ed.), Vol. 12. Ft. Collins, CO, USA,, Alaken Inc.,; 1998. L-amino acid oxidases and lactate dehydrogenases; pp. 579–598. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Morita T. Structure and function of snake venom cysteine-rich secretory proteins. Toxicon. 2004;44:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Teng M, Niu L, Liu Q, Huang Q, Hao Q. Crystal structure of the cysteine-rich secretory protein stecrisp reveals that the cysteine-rich domain has a K+ channel inhibitor-like fold. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12405–12412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Shen B, Guo M, Lou X, Duan Y, Cheng XP, Teng M, Niu L, Liu Q, Huang Q, Hao Q. Blocking effect and crystal structure of natrin toxin, a cysteine-rich secretory protein from Naja atra venom that targets the BKCa channel. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10145–10152. doi: 10.1021/bi050614m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Koike H, Sugiyama Y, Motoyoshi K, Wada T, Hishinuma S, Mita M, Morita T. Cloning and characterization of novel snake venom proteins that block smooth muscle contraction. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2708–2715. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki Y, Brown RL, Morita T. Purification and cloning of toxins from elapid venoms that target cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11331–11337. doi: 10.1021/bi026132h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipov AV, Levashov MY, Tsetlin VI, Utkin YN. Cobra venom contains a pool of cysteine-rich secretory proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL, Ching AT, Carvalho E, Faria F, Nishiyama MY, Jr., Ho PL, Diniz MR. Lachesis muta (Viperidae) cDNAs Reveal Diverging Pit Viper Molecules and Scaffolds Typical of Cobra (Elapidae) Venoms: Implications for Snake Toxin Repertoire Evolution. Genetics. 2006;173:877–889. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirthanan S, Gopalakrishnakone P, Gwee MC, Khoo HE, Kini RM. Non-conventional toxins from Elapid venoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:397–407. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry BG. From genome to "venome": molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome Res. 2005;15:403–420. doi: 10.1101/gr.3228405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Haggblad J, Heilbronn E. Isolation and pharmacological characterization of a new alpha-neurotoxin (alpha-AgTx) from venom of the viper Agkistrodon halys (Pallas) Toxicon. 1987;25:1019–1022. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(87)90167-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Sinauer Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kini RM. Molecular moulds with multiple missions: functional sites in three-finger toxins. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:815–822. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strydom DJ, Joubert FJ. The amino acid sequence of a weak trypsin inhibitor B from Dendroaspis Polylepis polylepis (black mamba) venom. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1981;362:1377–1384. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1981.362.2.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair DG, Fry BG, Alewood P, Kumar PP, Kini RM. Antimicrobial activity of omwaprin, a new member of the waprin family of snake venom proteins. Biochem J. 2007;402:93–104. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Wong HY, Desai M, Moochhala S, Kuchel PW, Kini RM. Identification of a novel family of proteins in snake venoms. Purification and structural characterization of nawaprin from Naja nigricollis snake venom. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40097–40104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouhammouch M, Brody EN. Temperature-dependent template switching during in vitro cDNA synthesis by the AMV-reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5443–5450. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng XC, Wang SX. Evidence that BmTXK beta-BmKCT cDNA from Chinese scorpion Buthus martensii Karsch is an artifact generated in the reverse transcription process. FEBS Lett. 2002;520:183–184. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaphiropoulos PG. Template switching generated during reverse transcription? FEBS Lett. 2002;527:326. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M. A new function evolved from gene fusion. Genome Res. 2000;10:1655–1657. doi: 10.1101/gr.165700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M, Betran E, Thornton K, Wang W. The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:865–875. doi: 10.1038/nrg1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiva P, Toporik A, Edelheit S, Peretz Y, Diber A, Shemesh R, Novik A, Sorek R. Transcription-mediated gene fusion in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:30–36. doi: 10.1101/gr.4137606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G, Reymond A, Dabbouseh N, Dermitzakis ET, Castelo R, Thomson TM, Antonarakis SE, Guigo R. Tandem chimerism as a means to increase protein complexity in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:37–44. doi: 10.1101/gr.4145906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon AE, Warren MS, Benkovic SJ. Assembly of an active enzyme by the linkage of two protein modules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1069–1073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patthy L. Modular assembly of genes and the evolution of new functions. Genetica. 2003;118:217–231. doi: 10.1023/A:1024182432483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]