Abstract

Background

Patients with sepsis typically require large resuscitation volumes, but the optimal type of fluid remains unclear. The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate current evidence on the effectiveness and safety of hydroxyethyl starch for fluid management in sepsis.

Methods

Computer searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library were performed using search terms that included hydroxyethyl starch; hetastarch; shock, septic; sepsis; randomized controlled trials; and random allocation. Additional methods were examination of reference lists and hand searching. Randomized clinical trials comparing hydroxyethyl starch with other fluids in patients with sepsis were selected. Data were extracted on numbers of patients randomized, specific indication, fluid regimen, follow-up, endpoints, hydroxyethyl starch volume infused and duration of administration, and major study findings.

Results

Twelve randomized trials involving a total of 1062 patients were included. Ten trials (83%) were acute studies with observation periods of 5 days or less, most frequently assessing cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic variables. Two trials were designed as outcome studies with follow-up for 34 and 90 days, respectively. Hydroxyethyl starch increased the incidence of acute renal failure compared both with gelatin (odds ratio, 2.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.13–5.83) and crystalloid (odds ratio, 1.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.22–2.71). In the largest and most recent trial a trend was observed toward increased overall mortality among hydroxyethyl starch recipients (odds ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 0.94–1.95), and mortality was higher (p < 0.001) in patients receiving > 22 mL·kg-1 hydroxyethyl starch per day than lower doses.

Conclusion

Hydroxyethyl starch increases the risk of acute renal failure among patients with sepsis and may also reduce the probability of survival. While the evidence reviewed cannot necessarily be applied to other clinical indications, hydroxyethyl starch should be avoided in sepsis.

Background

Sepsis and its frequent accompaniments – septic shock, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) – are major causes of multiple organ failure and mortality in hospitalized patients [1]. Overall hospital mortality rates of 21–47% have been reported among sepsis patients [2-5]. Acute renal failure (ARF) is a frequent complication [6]. Release of lipopolysaccharide endotoxin from the bacterial cell wall is among the mechanisms believed to initiate the signs, symptoms and physiologic and biochemical abnormalities characteristic of septic shock. Maldistribution of fluid in the microcirculation is typical of septic shock and results from endotoxin-induced endothelial damage. In severe sepsis, acute circulatory failure is often associated with hypovolemia and inadequate venous return, cardiac output and tissue nutrient flow [7]. Hypovolemia is a significant risk factor for mortality in sepsis [8], and these patients often require large volumes of resuscitation fluids [9]. Persistent vasodilation may also contribute to mortality among patients with sepsis [10]. Due to increased capillary permeability albumin efflux from plasma to the interstitium is increased three-fold in septic shock patients [11]. Septic patients frequently develop hypoproteinemia, which is significantly correlated with fluid retention and weight gain, development of ARDS and mortality [12].

Colloids are widely used as first-line treatment, in particular in Europe, usually in combination with crystalloids [13]. The artificial colloid hydroxyethyl starch (HES) has gained increasing acceptance for fluid management in a variety of indications. HES solutions differ according to their average molecular weight, molar substitution defined as the proportion of hydroxyethyl units substituted per glucose monomer, and substitution pattern as characterized by the ratio of substitution at the C2 and C6 positions on the glucose ring. More rapid clearance of HES molecules from plasma is observed after infusion of HES solutions with lower molar substitution, C2/C6 ratio and, to a smaller extent, molecular weight [14]. Impetus for the usage of HES has been generated by the higher unit acquisition cost of albumin [15]. Nevertheless, as previously reviewed [16], safety concerns about HES have been mounting. Some complications of HES are dose-related, and sepsis patients may require prolonged fluid administration typically with relatively high cumulative volumes. Consequently, the safety of HES in this indication needs to be appraised with particular care. The systematic review presented here is the first to assess randomized clinical trials of HES in sepsis.

Methods

Randomized clinical trials evaluating HES in sepsis were sought by computer searches of the MEDLINE and EMBASE bibliographic databases and the Cochrane Library. Search terms included: hydroxyethyl starch; hetastarch; shock, septic; sepsis; randomized controlled trials; and random allocation. Additionally, reference lists were examined and selected specialty journals searched by hand. Eligibility was not restricted on the basis of trial endpoints, type of HES solution, time period or language of publication. Both published and unpublished trials were eligible for inclusion.

From the trial reports data were extracted on numbers of patients randomized, specific indication, fluid regimen, follow-up and endpoints. Extracted data also included the daily and cumulative HES doses and the duration of HES administration. Close attention was paid to the investigators, time periods and trial data to avoid duplication in case the same trial was the subject of multiple reports and to ensure completeness of the included evidence in the event that multiple reports of the same trial contained partially non-overlapping data.

Major findings of the included trials were qualitatively summarized and tabulated. Due to heterogeneity in the control regimens, endpoints, length of follow-up and other trial design features a quantitative meta-analysis was not judged to be feasible.

Descriptive statistics included the median and interquartile range (IQR). Calculations were performed with R version 2.2.1 statistical software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Included trials

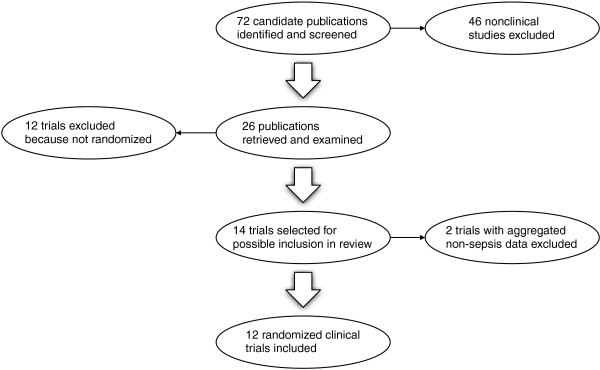

The selection process for randomized clinical trials is depicted in Fig. 1. Twelve trials with a total of 1062 patients were included [7,9,17-27]. None was unpublished. With 537 patients, the recent Efficacy of Volume Substitution and Insulin Therapy in Severe Sepsis (VISEP) trial accounted for approximately half the patients in the review [27]. Two included trials were described by Rackow and co-workers in the 1980s [7,9] and 5 by Boldt et al. in the 1990s [17-22]. The remaining 5 trials conducted by various teams of investigators were reported since 2000 [23-27]. One trial in a mixed population of patients with either septic or non-septic shock was excluded because septic shock was absent in approximately one-third of the patients and study endpoint results for septic versus other forms of shock were reported only in aggregate form [28,29]. Another trial involving 27 patients with severe sepsis and 36 with postoperative SIRS was also excluded due to aggregation of data [30]. Unaggregated data for that trial were requested from the investigators, but no response was received.

Figure 1.

Randomized trial selection process.

Trial characteristics

The characteristics of the included trials are summarized in Table 1. The median number of sepsis patients per trial was 30 (IQR, 26–64). Only three trials involved more than 100 patients [22,24,27]. Patients with severe sepsis or septic shock were enrolled in 6 trials [7,9,24-27]. Of the 6 other trials, 5 involved postoperative sepsis [17-22] and one sepsis with hypovolemia in ventilated and hemodynamically controlled patients [23].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included randomized trials

| Trial | n† | Indication | Fluid Regimen‡ | Follow-Up | Endpoints |

| Falk et al., 1988 [9] | 12 | Septic shock | 6% HES 450/0.7 or 5% albumin to 15 mm Hg target PAWP | 24 h | Coagulation |

| Rackow et al., 1989 [7] | 20 | Severe sepsis and systemic hypoperfusion | 10% HES 200/0.5 or 5% albumin to 15 mm Hg target PAWP or 2000 mL maximum | 45 min | Cardiorespiratory function and coagulation |

| Boldt et al., 1995 [17,18] | 30 | Sepsis after major surgery | 10% HES 200/0.5 or 20% albumin to 12–16 mm Hg target CVP, PCWP or both | 5 days | Endothelial-related coagulation and platelet function |

| Boldt et al., 1996 [19] | 30 | Sepsis secondary to major general surgery | 10% HES 200/0.5 or 20% albumin to 12–18 mm Hg target PCWP | 5 days | Cardiorespiratory and circulatory variables |

| Boldt et al., 1996 [20] | 42 | Sepsis secondary to major surgery | 6% HES 200/0.5, 20% albumin or pentoxifylline | 5 days | Circulating soluble adhesion molecules |

| Boldt et al., 1996 [21] | 28 | Sepsis secondary to major surgery | 10% HES 200/0.5 or 20% albumin to 10–15 mm Hg target PCWP | 5 days | Circulatory variables |

| Boldt et al., 1998 [22] | 150 | Postoperative sepsis | 10% HES 200/0.5 or 20% albumin to 12–15 mm Hg target PCWP | 5 days | Hemodynamics, laboratory data and organ function |

| Asfar et al., 2000 [23] | 34 | Sepsis and hypovolemia in ventilated and hemodynamically controlled patients | 500 mL 6% HES 200/0.62 or 4% succinylated modified fluid gelatin | 60 min | Hemodynamics and gastric mucosal acidosis |

| Schortgen et al., 2001 [24] | 129 | Severe sepsis or septic shock | 6% HES 200/0.62 up to 4 days or 80 mL·kg-1 cumulative dose or 3% gelatin | 34 days | ARF |

| Molnár et al., 2004 [25] | 30 | Septic shock with hypovolemia and acute lung injury | 6% HES 200/0.5 or 4% modified fluid gelatin to achieve ITBVI > 900 mL·m-2 | 60 min | Hemodynamics, EVLW and oxygenation |

| Palumbo et al., 2006 [26] | 20 | Severe sepsis in mechanically ventilated patients | 6% HES 130/0.4 or 20% albumin to maintain PCWP of 15–18 mm Hg | 5 days | Hemodynamic and oxygenation parameters |

| Brunkhorst et al., 2008 [27] | 537 | Severe sepsis or septic shock | 10% HES 200/0.5 (to 20 mL·kg-1·day-1 limit) or Ringer's lactate to target of ≥ 8 mm Hg CVP | 90 days | Morbidity and mortality |

Abbreviations: ARF, acute renal failure; CVP, central venous pressure; EVLW, extravascular lung water; HES, hydroxyethyl starch; ICU, intensive care unit; ITBVI, intrathoracic blood volume index; PAWP, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

†For trials with more than one indication, includes only patients with sepsis.

‡HES solutions specified by molecular weight/molar substitution.

HES with a molecular weight of 200 kDa and molar substitution of 0.5 (HES 200/0.5) was evaluated in 8/12 trials (67%). HES 200/0.62 was investigated in two trials and HES 130/0.4 and HES 450/0.7 in one each. The control fluid was 20% albumin in 6 trials, gelatin in 3, 5% albumin in 2 and crystalloid in one.

Ten trials (83%) were acute studies in which the observation periods ranged from less than 1 h to a maximum of 5 days. Only two trials were designed as outcome studies with follow-up of 34–90 days.

Cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic variables were endpoints of 7 trials and coagulation parameters of 3. Other evaluated endpoints consisted of extravascular lung water, gastric mucosal acidosis, circulating soluble adhesion molecules, ARF and morbidity and mortality.

HES posology

Patients in the included trials received HES for a median of 5 days (IQR, 1–5 days). The median daily HES dose was 12.6 mL·kg-1 (IQR, 11.0–13.7 mL·kg-1) and the median cumulative dose 49.8 mL·kg-1 (IQR, 22.6–63.0 mL·kg-1).

Major findings

Hemodynamic and cardiorespiratory variables were improved by HES 130/0.4 and HES 200/0.5 compared with 20% albumin [19,22,26] but not gelatin [25]. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score was also improved by HES 130/0.4 but not 20% albumin [26]. HES 200/0.5 either improved gastric intramucosal pH (pHi) compared with 20% albumin [21] or avoided a decline in pHi observed in 20% albumin recipients [19]. On the other hand, gelatin raised pHi and decreased CO2 gastric mucosal arterial gradient, while HES 200/0.62 did not display these beneficial effects [23].

HES 450/0.7 impaired coagulation, as judged by prolonged partial thromboplastin time, and decreased platelet count [9]. These undesirable effects were not encountered in patients receiving 5% albumin. HES 200/0.5 diminished factor VIII levels compared with 5% albumin [7]. Differences in coagulation and platelet count between HES 200/0.5 and 20% albumin were not observed in one trial [22]. Compared with crystalloid, HES 200/0.5 interfered with coagulation as indicated by a higher sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) coagulation subscore (p < 0.001) and greater median red blood cell transfusion requirement of 6 units (IQR, 4–12 units) vs. 4 units (IQR, 2–8 units) for the control group (p < 0.001) [27].

In a trial of 129 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock by Schortgen et al. [24], the groups randomized to receive HES 200/0.62 or gelatin were similar at baseline in severity of illness and serum creatinine. However, over the 34 day study observation period the incidence of ARF was increased in the HES 200/0.62 recipients (p = 0.018). In a multivariate analysis with adjustment for fluid loading before inclusion and mechanical ventilation at inclusion, HES 200/0.62 exposure was shown to be an independent risk factor for ARF (Table 2). At the conclusion of the study, ARF incidence in the HES 200/0.62 group (61%) exceeded that in the gelatin group (31%) by 30% based on Kaplan-Meier analysis. The median time to ARF among patients receiving HES 200/0.62 was 16 days. An earlier trial by Boldt and co-workers [22] failed to detect an effect of HES 200/0.5 on incidence of renal failure, possibly as a result of the short 5 day observation period. In the trial of Schortgen et al., a between-group difference in ARF incidence of only 11% was evident at the 5 day time point.

Table 2.

HES dose administered and major findings of included randomized trials

| Trial | Days on HES | Mean mL·kg-1 HES | Major Findings | |

| Daily | Cumulative | |||

| Falk et al., 1988 [9] | 1 | 70.5† | 70.5† | In HES 450/0.7 group PTT increased by 20 s (p = 0.01) and platelet count decreased by 158 × 103 mm-3 (p = 0.01); no significant PTT or platelet count change in albumin group |

| Rackow et al., 1989 [7] | 1 | 12.9† | 12.9† | FVIII:c declined 45% in the HES 200/0.5 group compared with 5% in the albumin group (p = 0.05) |

| Boldt et al., 1995 [17,18] | 5 | 8.5 | 42.3 | Plasma thrombomodulin increased in the albumin group and remained unchanged in the HES 200/0.5 group (p < 0.05); plasma protein C among HES 200/0.5 recipients increased on days 4 and 5 without corresponding change in the albumin group (p < 0.05); maximum platelet aggregation declined in both groups (p < 0.05) |

| Boldt et al., 1996 [19] | 5 | 11.0 | 55.2 | HES 200/0.5 but not albumin increased cardiac index, RVEF, Pao2/Fio2, Do2I and Vo2I and decreased SVRI (p < 0.05 for all comparisons); pHi decreased in albumin but not HES 200/0.5 group (p < 0.05) |

| Boldt et al., 1996 [20] | 5 | 12.7 | 63.7 | Circulating sELAM-1 and sICAM-1 concentrations reduced by HES 200/0.5 compared with albumin (p < 0.05 for both comparisons) |

| Boldt et al., 1996 [21] | 5 | 11.0 | 49.8 | Vasopressin, endothelin-1 and norepinephrine decreased and pHi increased in HES 200/0.5 but not albumin group (p < 0.05 for all comparisons); ANP increased by albumin but not HES 200/0.5 (p < 0.05) |

| Boldt et al., 1998 [22] | 5 | 12.5 | 62.4 | Pao2/Fio2, Do2I and Vo2I increased and lactate decreased by HES 200/0.5 but not albumin (p < 0.05 for all comparisons); no differences in incidence of renal failure, platelet count, PT or aPTT |

| Asfar et al., 2000 [23] | 1 | 7.9 | 7.9 | Gelatin but not HES 200/0.62 increased pHi (p < 0.001) and decreased CO2 gastric mucosal arterial gradient (p < 0.0005) |

| Schortgen et al., 2001 [24] | 4‡ | 14.0‡ | 31.0‡ | HES 200/0.62 exposure an independent risk factor for ARF (adjusted odds ratio, 2.57; CI 1.13–5.83) |

| Molnár et al., 2004 [25] | 1 | 14.3† | 14.3† | No differences detected in ITBVI, EVLW or Pao2/Fio2 |

| Palumbo et al., 2006 [26] | 5 | --§ | --§ | Target PCWP of 15–18 mm Hg maintained by both colloids; temperature, MAP, PAP, CVP, heart rate and urine output remained stable without differences between groups; HES 130/0.4, but not albumin, increased cardiac index and several oxygenation parameters (Pao2/Fio2, Do2I and Vo2I) and decreased APACHE II score (p < 0.05 for all within-group comparisons) |

| Brunkhorst et al., 2008 [27] | 21 | --§ | 70.4¶ | Greater ARF incidence in HES 200/0.5 group (odds ratio, 1.81; CI, 1.22–2.71; p = 0.002); increased mortality at higher HES 200/0.5 doses (odds ratio, 3.08; CI, 1.78–5.37; p < 0.001) |

Abbreviations: ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ARF, acute renal failure; CI, 95% confidence interval; CVP, central venous pressure; Do2I, oxygen delivery index; EVLW, extravascular lung water; HES, hydroxyethyl starch; FVIII:c, factor VIII coagulant activity; ITBVI, intrathoracic blood volume index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; Pao2/Fio2, ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; pHi, gastric intramucosal pH; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; sELAM-1, soluble endothelial leucocyte adhesion molecule-1; sICAM-1, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; SVRI, systemic vascular resistance index; Vo2I, oxygen consumption index

†Calculated from reported volume administered assuming 70 kg body weight.

‡Actual days on HES not specified. Maximum of 4 days imposed after start of study, and percentage of patients receiving HES longer not indicated. Daily dose stated for day 1 only. Cumulative dose reported as median.

§Not reported.

¶Median.

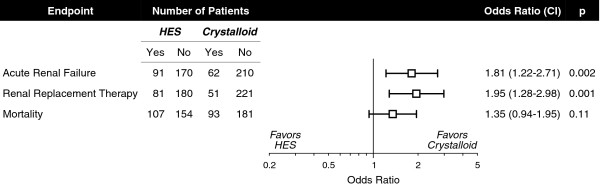

The recent multicenter VISEP trial assessing morbidity and mortality up to 90 days in 537 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock is the first large-scale outcome study of HES 200/0.5 in any clinical indication [27]. The HES 200/0.5 and crystalloid groups were well-matched at baseline in severity of illness and serum creatinine. HES 200/0.5 infusion compromised renal function (p = 0.02) as reflected by a higher SOFA renal subscore than that of the control group. The incidence of ARF and use of renal replacement therapy (RRT) were both increased by HES 200/0.5 (Fig. 2). RRT usage was positively correlated with cumulative HES 200/0.5 dose (p < 0.001). Even in the subset of patients receiving exclusively lower HES 200/0.5 doses (≤ 22 mL·kg-1), higher ARF incidence (p = 0.04) and RRT utilization (p = 0.03) were demonstrated in comparison with the crystalloid control group.

Figure 2.

Incidence of acute renal failure, use of renal replacement therapy and mortality in patients receiving HES or crystalloid. Abbreviations: CI, 95% confidence interval; HES, hydroxyethyl starch. Based on the data of Brunkhorst et al. [27].

In the VISEP trial there was also an overall trend toward increased mortality among HES 200/0.5 recipients (Fig. 2). Mortality at 90 days was correlated with cumulative HES 200/0.5 dose (p = 0.001) and significantly increased (p < 0.001) in patients receiving > 22 mL·kg-1 HES 200/0.5 (58%) for at least one day than lower doses (31%).

Discussion

Until relatively recently, randomized trial evidence concerning HES for fluid management in sepsis patients has stemmed almost entirely from small acute studies, often focused on cardiorespiratory and hemodynamic endpoints. These trials were thus not designed to evaluate safety or outcomes, and renal function in particular was not evaluated. The report of Schortgen et al. [24] was to first to raise serious concern that HES might adversely affect renal function in sepsis. The results of that trial should perhaps have been unsurprising in light of earlier randomized trials indicating deleterious effects of HES on the kidney in cardiac [31] and abdominal surgery [32] and renal transplantation [33]. The VISEP trial [27] has now furnished convincing confirmation that HES increases ARF incidence in sepsis.

The administration of HES 200/0.5 in the VISEP trial has also put to rest the argument that the adverse renal effects observed by Schortgen et al. might have been due to their use of the more highly substituted HES 200/0.62 solution. On the other hand it should be recognized that the results of sepsis trials involving repeated HES infusion over a period of several days or more cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other settings such as postoperative fluid management involving lower HES doses for a shorter time.

The VISEP trial has also provided the first evidence that HES may increase mortality among sepsis patients. A trend toward higher mortality was observed among all recipients of HES compared with crystalloid, and mortality was significantly increased by higher HES doses. These data are in contrast to the results of the SAFE trial [34] comparing 4% albumin with normal saline. In the subset of 1218 SAFE trial patients with severe sepsis, a trend toward reduced mortality was evident in the albumin group (odds ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.63–1.04; p = 0.09). In light of these disparate survival trends, a need exists for an adequately powered outcome trial directly comparing HES and albumin in sepsis.

Schortgen et al. detected no effect of HES 200/0.62 on survival; however, the duration of follow-up in their trial was 34 days. In the VISEP trial the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two randomized groups began to diverge only at approximately 30 days and were clearly separated thereafter. It is thus possible that in the trial of Schortgen et al. a mortality difference might have become apparent with longer follow-up.

The mechanisms that might account for undesirable HES effects on kidney function and possibly survival in sepsis are not understood. One putative mechanism is renal ischemia [24]. HES has been shown to increase plasma viscosity in vitro compared with albumin [35]. In a rat model of severe hemorrhagic shock, both 6% HES and 5% albumin restored macrocirculatory function as measured by mean arterial pressure [36]. However, only albumin completely returned mesenteric microcirculatory blood flow to the baseline level. Furthermore, albumin was effective in restoring mesenteric lymphatic output, while HES was not (p < 0.05).

Since more than 30 years ago there has been evidence that HES might impair reticuloendothelial system (RES) function, thereby impairing host defenses against sepsis and possibly contributing to multiple organ failure, including ARF, and mortality [37]. A substantial proportion of administered HES cannot be metabolized acutely and undergoes uptake and storage by the RES, most notably in macrophages including those localized in the kidney [38-42]. In a quantitative necropsy specimen study of 12 young adult patients who had died due to sepsis and multi-organ failure after receiving a mean of 258 mL·day-1 HES 200/0.5, the highest mean major organ HES tissue concentration was measured in the kidney (13.7 mg·g-1) [43]. The effects of plasma substitutes on RES function in mice were investigated by intraperitoneal injection of Salmonella enteritidis endotoxin [37]. Host defenses against this endotoxin are mediated by RES macrophages. Prior infusion of HES but not plasma increased the lethality of endotoxin injected either 1 h (p < 0.05) or 3 h (p < 0.01) subsequently. Similarly, in a murine hemorrhagic shock model no HES-resuscitated animal survived intraperitoneal injection of live E. coli at 1 h after resuscitation, whereas survival with shed blood resuscitation was 64% [44]. In contrast to these two studies involving acute septic challenge within 1–3 h after HES administration, a delayed challenge in the form of cecal ligation and puncture 48 h after HES infusion did not increase mortality in rats [45]. In any case, there is at present no clinical evidence indicating HES-mediated impairment of RES function in sepsis, and clinical studies will be required to delineate the role, if any, of the RES in explaining the observed deleterious effects of HES among septic patients.

A variety of HES solutions are available that differ in average molecular weight, molar substitution, C2/C6 ratio and solvent. It has often been claimed that a particular HES solution may be devoid of safety problems displayed by others. Several recent evidence-based reviews have challenged this contention [16,46-48]. Similar types of complications, including impaired kidney function [48], have been encountered clinically across the entire spectrum of HES solutions. These adverse effects appear to reflect the intrinsic pharmacologic properties of the HES molecule rather than differences between individual HES solutions [49]. For instance, HES 130/0.4 was shown to impair renal function assessed by four sensitive markers in a randomized trial of elderly cardiac surgery patients [50]. HES 450/0.7 in Ringer's lactate vehicle was independently associated with reduced glomerular filtration rate in a retrospective study of 238 consecutive coronary artery bypass graft patients [51]. The safety of either solution for fluid management in sepsis would need to be demonstrated in clinical trials.

Conclusion

Compelling evidence is now at hand indicating that HES infusion places sepsis patients at increased risk for ARF. New data also suggest the possibility of poorer survival among sepsis patients receiving HES, especially higher doses. Clearly, HES 200/0.5 and HES 200/0.62 cannot now be recommended in sepsis. The effectiveness and safety of other HES solutions in this indication remain to be determined in future clinical trials.

List of abbreviations

ARDS: Adult respiratory distress syndrome; ARF: Acute renal failure; HES: Hydroxyethyl starch; IQR: Interquartile range; pHi: Gastric intramucosal pH; RES: Reticuloendothelial system; RRT: Renal replacement therapy; SIRS: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CJW is sole author.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

References

- Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams P, Pothier L, Boyce PD, Christiani DC. Clinical predictors of and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: potential role of red cell transfusion. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000165566.82925.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittet D, Thievent B, Wenzel RP, Li N, Auckenthaler R, Suter PM. Bedside prediction of mortality from bacteremic sepsis. A dynamic analysis of ICU patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:684–693. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weycker D, Akhras KS, Edelsberg J, Angus DC, Oster G. Long-term mortality and medical care charges in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2316–2323. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000085178.80226.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu DT, Platt R, Lanken PN, Black E, Sands KE, Schwartz JS, Hibberd PL, Graman PS, Kahn KL, Snydman DR, Parsonnet J, Moore R, Bates DW. Relationship of pulmonary artery catheter use to mortality and resource utilization in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2734–2741. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098028.68323.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun L, Riedel AA, Cooper LM. Severe sepsis in managed care: analysis of incidence, one-year mortality, and associated costs of care. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10:521–530. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2004.10.6.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Biesen W, Yegenaga I, Vanholder R, Verbeke F, Hoste E, Colardyn F, Lameire N. Relationship between fluid status and its management on acute renal failure (ARF) in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with sepsis: a prospective analysis. J Nephrol. 2005;18:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackow EC, Mecher C, Astiz ME, Griffel M, Falk JL, Weil MH. Effects of pentastarch and albumin infusion on cardiorespiratory function and coagulation in patients with severe sepsis and systemic hypoperfusion. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:394–398. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J, Dellamonica P, Gouin F, Lepoutre A, Mercier JC, Offenstadt G, Régnier B. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. A multicenter prospective study in intensive care units. French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. JAMA. 1995;274:968–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.12.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk JL, Rackow EC, Astiz ME, Weil MH. Effects of hetastarch and albumin on coagulation in patients with septic shock. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:412–415. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb05751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld AB, Bronsveld W, Thijs LG. Hemodynamic determinants of mortality in human septic shock. Surgery. 1986;99:140–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik PE, Iglesias J. Would the colloid detractors please sit down! Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2652–2654. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangialardi RJ, Martin GS, Bernard GR, Wheeler AP, Christman BW, Dupont WD, Higgins SB, Swindell BB. Hypoproteinemia predicts acute respiratory distress syndrome development, weight gain, and death in patients with sepsis. Ibuprofen in Sepsis Study Group. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3137–3145. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schortgen F, Deye N, Brochard L. Preferred plasma volume expanders for critically ill patients: results of an international survey. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2222–2229. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treib J, Haass A, Pindur G, Seyfert UT, Treib W, Grauer MT, Jung F, Wenzel E, Schimrigk K. HES 200/0.5 is not HES 200/0.5. Influence of the C2/C6 hydroxyethylation ratio of hydroxyethyl starch (HES) on hemorheology, coagulation and elimination kinetics. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:1452–1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL. Fluid management: the pharmacoeconomic dimension. Crit Care. 2000;4:S33–35. doi: 10.1186/cc969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedermann CJ. Hydroxyethyl starch-can the safety problems be ignored? Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:583–594. doi: 10.1007/s00508-004-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Heesen M, Welters I, Padberg W, Martin K, Hempelmann G. Does the type of volume therapy influence endothelial-related coagulation in the critically ill? Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:740–746. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Müller M, Heesen M, Heyn O, Hempelmann G. Influence of different volume therapies on platelet function in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:1075–1081. doi: 10.1007/BF01699231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Heesen M, Müller M, Pabsdorf M, Hempelmann G. The effects of albumin versus hydroxyethyl starch solution on cardiorespiratory and circulatory variables in critically ill patients. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:254–261. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Müller M, Heesen M, Neumann K, Hempelmann GG. Influence of different volume therapies and pentoxifylline infusion on circulating soluble adhesion molecules in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:385–391. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Mueller M, Menges T, Papsdorf M, Hempelmann G. Influence of different volume therapy regimens on regulators of the circulation in the critically ill. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:480–487. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Müller M, Mentges D, Papsdorf M, Hempelmann G. Volume therapy in the critically ill: is there a difference? Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:28–36. doi: 10.1007/s001340050511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfar P, Kerkeni N, Labadie F, Gouëllo JP, Brenet O, Alquier P. Assessment of hemodynamic and gastric mucosal acidosis with modified fluid versus 6% hydroxyethyl starch: a prospective, randomized study. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1282–1287. doi: 10.1007/s001340000606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schortgen F, Lacherade JC, Bruneel F, Cattaneo I, Hemery F, Lemaire F, Brochard L. Effects of hydroxyethylstarch and gelatin on renal function in severe sepsis: a multicentre randomised study. Lancet. 2001;357:911–916. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z, Mikor A, Leiner T, Szakmány T. Fluid resuscitation with colloids of different molecular weight in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1356–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo D, Servillo G, D'Amato L, Volpe ML, Capogrosso G, De Robertis E, Piazza O, Tufano R. The effects of hydroxyethyl starch solution in critically ill patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2006;72:655–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N, Moerer O, Gruendling M, Oppert M, Grond S, Olthoff D, Jaschinski U, John S, Rossaint R, Welte T, Schaefer M, Kern P, Kuhnt E, Kiehntopf M, Hartog C, Natanson C, Loeffler M, Reinhart K. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. The German Competence Network Sepsis (SepNet) N Engl J Med. 2008;358:125–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt MT, Rackow EC. Colloid osmotic pressure and fluid resuscitation with hetastarch, albumin, and saline solutions. Crit Care Med. 1982;10:159–162. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackow EC, Falk JL, Fein IA, Siegel JS, Packman MI, Haupt MT, Kaufman BS, Putnam D. Fluid resuscitation in circulatory shock: a comparison of the cardiorespiratory effects of albumin, hetastarch, and saline solutions in patients with hypovolemic and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1983;11:839–850. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneman TF, Oude Nijhuis J, Woittiez AJ. Human albumin and starch administration in critically ill patients: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:305–309. doi: 10.1007/BF03040900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Knothe C, Schindler E, Hammermann H, Dapper F, Hempelmann G. Volume replacement with hydroxyethyl starch solution in children. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:661–665. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumle B, Boldt J, Piper S, Schmidt C, Suttner S, Salopek S. The influence of different intravascular volume replacement regimens on renal function in the elderly. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1124–1130. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199911000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cittanova ML, Leblanc I, Legendre C, Mouquet C, Riou B, Coriat P. Effect of hydroxyethylstarch in brain-dead kidney donors on renal function in kidney-transplant recipients. Lancet. 1996;348:1620–1622. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07588-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAFE Study Investigators A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2247–2256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro VJ, Astiz ME, Rackow EC. Effect of crystalloid and colloid solutions on blood rheology in sepsis. Shock. 1997;8:104–107. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paes-da-Silva F, Gonzalez AP, Tibiriçá E. Effects of fluid resuscitation on mesenteric microvascular blood flow and lymphatic activity after severe hemorrhagic shock in rats. Shock. 2003;19:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildt B, Bouveng R, Sollenberg M. Plasma substitute induced impairment of the reticuloendothelial system function. Acta Chir Scand. 1975;141:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WL, Fukushima T, Rutherford RB, Walton RP. Intravascular persistence, tissue storage, and excretion of hydroxyethyl starch. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1970;131:965–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer U, Kult J, Forster H. Ascites als Komplikation hepatischer Speicherung von Hydroxyethylstärke (HES) bei Langzeitdialyse. Klin Wochenschr. 1984;62:862–866. doi: 10.1007/BF01712005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienes HP, Gerharz CD, Wagner R, Weber M, John HD. Accumulation of hydroxyethyl starch (HES) in the liver of patients with renal failure and portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 1986;3:223–227. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(86)80030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurecka W, Szepfalusi Z, Parth E, Schimetta W, Gebhart W, Scheiner O, Kraft D. Hydroxyethylstarch deposits in human skin – a model for pruritus? Arch Dermatol Res. 1993;285:13–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00370817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auwerda JJ, Wilson JH, Sonneveld P. Foamy macrophage syndrome due to hydroxyethyl starch replacement: a severe side effect in plasmapheresis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:1013–1014. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasewitz P, Kroh U, Löwenstein O, Krämer M, Lennartz H. Quantitative Untersuchungen zur Gewebsspeicherung von mittelmolekularer Hydroxyethylstärke 200/0,5 bei Patienten mit Multiorganversagen. J Anaesth Intensivbeh. 1998;3:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- van Rijen EA, Ward JJ, Little RA. Effects of colloidal resuscitation fluids on reticuloendothelial function and resistance to infection after hemorrhage. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:543–549. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.4.543-549.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatney CH, Chaudry IH. Hydroxyethylstarch administration does not depress reticuloendothelial function or increase mortality from sepsis. Circ Shock. 1984;13:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron ME, Wilkes MM, Navickis RJ. A systematic review of the comparative safety of colloids. Arch Surg. 2004;139:552–563. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork K. Pruritus precipitated by hydroxyethyl starch: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson IJ. Renal impact of fluid management with colloids: a comparative review. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:721–738. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedermann CJ. Renal failure in septic patients receiving hydroxyethyl starch. Minerva Anestesiol. 2007;73:441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Brenner T, Lehmann A, Lang J, Kumle B, Werling C. Influence of two different volume replacement regimens on renal function in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery: comparison of a new starch preparation with gelatin. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:763–769. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Avorn J. Hydroxyethyl starch and change in renal function in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1046–1049. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]