Abstract

Background

Since 1990 non communicable diseases and injuries account for the majority of death and disability-adjusted life years in Latin America. We analyzed the relationship between the global burden of disease and Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) conducted in Latin America that were published in the five leading medical journals.

Methodology/Principal Findings

We included all RCTs in humans, exclusively conducted in Latin American countries, and published in any of the following journals: Annals of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal, Journal of the American Medical Association, Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine. We described the trials and reported the number of RCTs according to the main categories of the global burden of disease. Sixty-six RCTs were identified. Communicable diseases accounted for 38 (57%) reports. Maternal, perinatal, and nutritional conditions accounted for 19 (29%) trials. Non-communicable diseases represent 48% of the global burden of disease but only 14% of reported trials. No trial addressed injuries despite its 18% contribution to the burden of disease in 2000.

Conclusions/Significance

A poor correlation between the burden of disease and RCTs publications was found. Non communicable diseases and injuries account for up to two thirds of the burden of disease in Latin America but these topics are seldom addressed in published RCTs in the selected sample of journals. Funding bodies of health research and editors should be aware of the increasing burden of non communicable diseases and injuries occurring in Latin America to ensure that this growing epidemic is not neglected in the research agenda and not affected by publication bias.

Introduction

It has been estimated that less than 10% of health research spending is directed toward diseases or conditions that account for 90% of the global burden of disease, a phenomenon referred to as the “10/90 gap”.[1] The gap is also reflected in the low proportion of publications arising from research in low and middle income countries, where most of the global burden of disease occurs.[2]

Addressing context specific research questions are fundamental to designing interventions that improve health. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard to assess the effectiveness of interventions. An unbiased design and adequate reporting of RCTs that specifically address diseases which affect low and middle income countries can have an impact in changing medical practice and influencing public health policy.

Five of the world's leading medical journals—Annals of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal (BMJ), Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Lancet, and New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM)—have together the highest impact in medical research, and therefore, they can have a large influence on clinical medicine and public health worldwide. In relation to this group of medical journals, one of its editors stated that “Their international success brings global responsibilities to the communities they serve and profit from…” and that they should raise “the priority of papers from less-developed countries in line with global burdens of disease”.[3] Unfortunately, there is good evidence of the under representation of research addressing common conditions from developing countries in these leading journals.[2], [4], [5], [6]

Bibliometric analyses—a set of methods used to study or measure texts and information—have been done to illustrate the gaps of the published medical literature, either in terms of subjects covered, representation of journal’s editorial boards, and specifically, the under-representation of low and middle income countries in high-impact general medical journals.[6], [7], [8], [9]

Latin-American and Caribbean countries have experienced a rapid epidemiological transition and since 1990 non communicable diseases and injuries already account for the majority of death and disability-adjusted life years in the region.[10], [11] No previous studies have investigated the relationship between RCTs and the burden of disease in Latin America. Description of this relationship can provide information about gaps between the health needs and the research conducted in the region. This information can contribute to the establishment of a research agenda and prioritize neglected conditions.

We analyzed the relationship between the global burden of disease and RCTs conducted in Latin America published in five leading medical journals.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We included all RCT s in humans, exclusively conducted in Latin American countries (by this we mean that the population was located in Latin America irrespective of the origin of the researcher) and published in any of the following journals: Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet and NEJM. The definition used for RCTs was an experiment in which investigators randomly allocate eligible participants into an intervention group (arm) each of which receives one or more of the interventions (or none) that are being compared.[12]

Identification of the trials

We searched the PubMed database registers from 1990 up to December 2006 using the Cochrane Sensitive Search Strategy, which is highly sensitivity to identify RCTs, and combined it with the terms “Latin America” or “Latin America” and all the country names from the region.[13] We limited the search strategy to the five selected medical journals (Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, JAMA, Lancet and NEJM). (See Appendix S1 for the full search strategy).

Data extraction

From selected trials, the following data were extracted: name of the first author, year of publication, country(ies) where the study was conducted, number of participants, description of disease evaluated according to groups of global burden of disease and type of funding. Data extraction and data entry was made independently by two reviewers. Differences in data extraction were resolved by a third party.

Data analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis listing the number of RCTs, participants and countries in which the studies were conducted. We also reported the number of RCTs according to the main categories of the global burden of disease.

Results

Of 181 reports initially obtained, 66 (36%) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were retrieved for the analysis.

Table 1 displays the general characteristics of the reports included. The majority of the trials were published in Lancet and the countries with the highest numbers of publications were Brazil and Mexico. Cluster trials accounted for one-fifth of all the publications. We found no defined trend in the frequency of publications during this time. Most of the trials were non-commercial.

Table 1. General Characteristics of the reports included.

| Publications per journal | n (%) |

| Lancet | 30 (46) |

| BMJ | 12 (18) |

| NEJM | 12(18) |

| JAMA | 6 (9) |

| Annals | 6 (9) |

| Publications per country* | n |

| Brazil | 14 |

| Mexico | 12 |

| Argentina | 9 |

| Chile | 6 |

| Venezuela | 5 |

| Haiti | 5 |

| Peru | 5 |

| Colombia | 4 |

| Unit of randomization | n (%) |

| Individuals | 54 (81) |

| Clusters | 12 (19) |

| Date of publication | n (%) |

| 1990–1992 | 10 (15) |

| 1993–1995 | 14 (22) |

| 1996–1998 | 10 (15) |

| 1999–2001 | 8 (12) |

| 2002–2004 | 12 (18) |

| 2005–2006 | 12 (18) |

| Type of funding | n(%) |

| Non commercial | 42 (64) |

| Commercial | 6 (9) |

| Both | 12 (18) |

| Not reported | 6(9) |

| Sample Size | mean (range) |

| Patients included per report | 275 (26 to 348,139) |

| Conditions according to the Global Burden of Disease Study | n (%) |

| Communicable diseases | 38 (57) |

| Maternal perinatal and nutritional | 19 (29) |

| Non-Communicable diseases | 9 (14) |

Communicable diseases accounted for 38 (57%) reports. Maternal, perinatal, and nutritional conditions accounted for 19 (29%) trials, and 9 (14%) addressed non-communicable diseases. Within the latter group, 4 trials evaluated cardiovascular disease, 1 cancer and 4 other non-communicable diseases. We found no RCTs assessing interventions for injuries. The most common individual condition evaluated was traveler’s diarrhea, which was studied in 4 (6%) of the trials. (See table 2 for the full details of reports included).

Table 2. Full details of the included reports.

| Year | Journal | Participants | Cluster | Funding | Specific Condition | Global Burden of Disease Classification | Countries |

| 1990 | Lancet | 81621 | no | Non-commercial | Salmonela Tiphy | Communicable | Chile |

| 1990 | Jama | 227 | no | Non-commercial | traveller’s diahrrea | Communicable | Mexico |

| 1991 | NEJM | 101 | no | Commercial | Infant meningitis | Communicable | Costa Rica |

| 1991 | NEJM | 1194 | no | Non-commercial | Hipertensive disorders in pregnancy | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Argentina |

| 1991 | NEJM | 86 | no | Commercial | Infant diarrea | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Costa Rica |

| 1992 | NEJM | 2235 | no | Non-commercial | Delivery and low birth weight | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Argentina, Brasil, Cuba, and Mexico |

| 1992 | Jama | 191 | no | Both | traveller’s diahrrea | Communicable | Mexico |

| 1992 | NEJM | 110 | no | Not reported | Leshmaniasis | Communicable | Colombia |

| 1992 | Lancet | 29113 | no | Non-commercial | Lepra | Communicable | Venezuela |

| 1992 | Jama | 278 | no | Commercial | DTP vaccine response | Communicable | Chile |

| 1993 | Lancet | 2606 | no | Non-commercial | Delivery, episiotomy | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Argentina |

| 1993 | Annals | 126 | no | Commercial | Artritis reumatoidea | NCD | Mexico |

| 1993 | Lancet | 11124 | si | Both | Diarrhea and respiratory infections in infants | Communicable | Haiti |

| 1993 | Lancet | 118 | no | Non-commercial | HiV and Tuberculosis | Communicable | Haiti |

| 1993 | NEJM | 275 | no | Both | Diarrea | Communicable | Peru |

| 1993 | Lancet | 1548 | no | Non-commercial | Malaria | Communicable | Colombia |

| 1993 | Lancet | 159 | no | Non-commercial | Infant diarrea | Communicable | Guatemala and Brazil |

| 1993 | Lancet | 4534 | no | Commercial | Acute Miocardial Infarction | NCD | Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela |

| 1994 | Lancet | 88 | no | Non-commercial | traveller’s diahrrea | Communicable | Belize |

| 1994 | Lancet | 1563 | no | Not reported | Colera | Communicable | Peru |

| 1994 | Lancet | 275 | no | Non-commercial | Kangaroo low birth weight infants | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Ecuador |

| 1994 | Lancet | 516 | no | Not reported | Heart Failure | NCD | Argentina |

| 1994 | Lancet | 141 | no | Non-commercial | Infant nutrition | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Honduras |

| 1994 | Lancet | 1240 | no | Non-commercial | Diarrea e infecciones respitatorias pediatricas | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Brasil |

| 1996 | Lancet | 130 | no | Non-commercial | Chagas | Communicable | Brasil |

| 1997 | NEJM | 2207 | no | Both | Rotavirus Diarrrea | Communicable | Venezuela |

| 1997 | BMJ | 472 | no | Non-commercial | Childhood Pneumonia | Communicable | Brasil |

| 1997 | Lancet | 113 | no | Non-commercial | Filariasis in childrem | Communicable | Haiti |

| 1997 | Annals | 187 | no | Not reported | Leshmaniasis | Communicable | Colombia |

| 1997 | Lancet | 202 | no | Both | Coronary Heart Disease | NCD | Argentina |

| 1997 | BMJ | 591 | no | Non-commercial | Blood pressure of children | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Argentina |

| 1998 | Annals | 176 | no | Non-commercial | Malaria | Communicable | Colombia |

| 1998 | Lancet | 627 | no | Non-commercial | Haemofilus in infants | Communicable | Chile |

| 1998 | NEJM | 53 | no | Not reported | Acute Respiratory Syndrome | Communicable | Brasil |

| 1999 | BMJ | 101 | no | Both | Snake bite | Communicable | Brasil |

| 1999 | Jama | 543 | no | Non-commercial | Meningitis | Communicable | Chile |

| 1999 | Lancet | 130 | no | Non-commercial | Breastfeeding | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Mexico |

| 2000 | Lancet | 233 | no | Non-commercial | Tuberculosis | Communicable | Haiti |

| 2000 | Lancet | 12926 | no | Non-commercial | HIV | Communicable | Nicaragua |

| 2000 | Annals | 42 | no | Non-commercial | HIV | Communicable | Haiti |

| 2000 | NEJM | 135 | no | Commercial | Infant diarrea | Communicable | Peru |

| 2001 | Jama | 1193 | no | Both | Respiratory tract infection in infants | Communicable | Dominicana |

| 2002 | BMJ | 2913 | si | Both | Leshmaniasis | Communicable | Venezuela |

| 2002 | Lancet | 26 | no | Non-commercial | Altitude polycythaemia | NCD | Bolivia |

| 2003 | BMJ | 301 | no | Non-commercial | Agitation in mental health | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Brasil |

| 2003 | Lancet | 240 | no | Non-commercial | Depression | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Chile |

| 2004 | Lancet | 70 clusters | si | Non-commercial | Infant and maternal health | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Honduras |

| 2004 | BMJ | 210 | si | Non-commercial | Snake bite | Communicable | Ecuador |

| 2004 | BMJ | 139 | si | Non-commercial | Infant malnutrition | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Jamaica |

| 2004 | Lancet | 149276 | si | Non-commercial | Delivery | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Argentina, Brasil, Cuba, Guatemala and Mexico |

| 2004 | Jama | 795 | si | Non-commercial | Infant anaemia and nutrition | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Mexico |

| 2004 | BMJ | 120 | no | Non-commercial | Tetanus | Communicable | Brasil |

| 2004 | NEJM | 68 | no | Not reported | Cardia arrest | NCD | Brasil |

| 2004 | NEJM | 120 | no | Both | Neurocisticercosys | Communicable | Peru |

| 2005 | Lancet | 348139 | si | Non-commercial | Tuberculosis | Communicable | Brasil |

| 2005 | Lancet | 350 | no | Non-commercial | Breastfeeding | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Brasil |

| 2005 | BMJ | 1518 | no | Non-commercial | Heart Failure | NCD | Argentina |

| 2005 | Lancet | 277 | si | Non-commercial | Infan nutrition | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Peru |

| 2005 | Annals | 210 | no | Both | traveller’s diahrrea | Communicable | Mexico |

| 2005 | NEJM | 162 | no | Both | Lupus | NCD | Mexico |

| 2006 | BMJ | 232 | no | Non-commercial | Depression | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Jamaica |

| 2006 | Lancet | 476 | no | Non-commercial | Infant anaemia | Maternal, perinatal and nutrition | Mexico |

| 2006 | BMJ | 10049 | si | Both | Dengue | Communicable | Venezuela |

| 2006 | Lancet | 2373 | si | Non-commercial | Parasites | Communicable | Ecuador |

| 2006 | BMJ | 10954 | si | Non-commercial | HIV | Communicable | Mexico |

| 2006 | Annals | 30 | no | Non-commercial | Glioblastoma | NCD | Mexico |

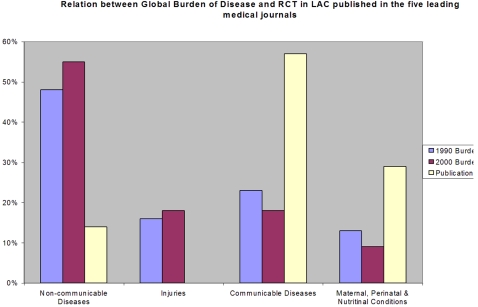

We found an overall poor correlation between the global burden of disease and the topic of the published RCTs conducted in Latin America. The mismatch is evident in the following figures: non-communicable diseases represent 48% of the burden of disease and 14% of the RCTs; no RCTs addressed injuries despite these representing 18% of the burden of disease in 2000 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relation between Global Burden of Disease and RCTs in LAC published in the five leading medical journals.

The figure shows an evident mismatch: non-communicable diseases represented 48% of the burden of disease in LAC and 14% of the RCTs. No RCTs addressed injuries despite these representing 18% of the DALYs in 2000.

Discussion

There is an evident mismatch between the burden of disease in and publications from Latin America. Non communicable diseases and injuries account for up to two thirds of the burden of disease in Latin America but these topics are seldom addressed in published RCTs in the selected sample of journals. Most of the reports that were retrieved evaluated infectious diseases, and within this group, the predominant condition studied was traveler’s diarrhea, a condition that may be more relevant to travelers from developed countries visiting less developed areas. Previous studies have reported the paucity of RCTs addressing the diseases of low and middle income countries.[5], [14], [15] However, to the best of our knowledge previous studies have not explored the relation between global burden of disease and RCTs in Latin America.

The gap identified in our study may have different explanations including lack of original research that mirror the burden of disease or a higher rate of RCTs publications addressing communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional conditions. The latter could be due to better quality of the design and reporting of the original studies. Alternatively editors and reviewers from the leading journals could be biased to include publications from Latin America when they focus on these conditions.

Why is important to conduct RCTs in Latin America?

As previously stated, context is crucial to decide which interventions are effective in specific populations because the effect—and therefore the impact—of some interventions could differ according to the setting. This is of particular relevance for those interventions that address behavioral modifications or involve health services.[16] Preventive interventions in injuries targeting behaviors that could be strongly influenced by cultural conditions or the adherence to medication in chronic conditions like cardiovascular diseases are some of the situations where RCTs are needed. A good example of this type of research is the DIAL Trial which addressed the case management of patients with chronic heart failure.[17] Furthermore, for chronic diseases the relevant outcome of interest is quality of life, so local evidence is necessary since this type of “soft” outcome is more culturally dependent. Another important reason to conduct trials in the region is that certain diseases predominantly occur in Latin America, such as Chagas disease[18] or Hemorrhagic Argentine Fever. These conditions may be of more interest to the region’s population and scientific community.

Why is important to publish the results of the RCTs?

A fundamental step after study completion is to publish the findings in scientific journals. The publication in the five leading medical journals, in particular, can influence clinical practice and policy.[19] These journals are particularly relevant in low and middle income where limited resources require that medical libraries subscribe to only a few international journals, and therefore, prioritize those with the higher impact. The publication of RCTs conducted on the region will not only disseminate the results appropriately but will also raise the awareness of the topic and potentially could help to increase the funding for research in these conditions.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is that we only considered five leading medical journals. We acknowledge that many of the trials conducted in Latin America may have been published in different journals, however we considered that those published on the leading journals will have the larger visibility and impact amongst the medical and health care community.

Another important limitation is that we included RCTs exclusively conducted in Latin America and, therefore, we excluded international trials which may have enrolled participants from this region. Most of the international trials are sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, which may answer important questions but are less likely to influence the public health of low and middle income countries in the short term.[20] Nonetheless, the Latin America region has also seen good examples of international trials that study generic drugs for prevalent diseases or conditions with direct relevance to the region. For example, Latin America has had an active participation in the MRC CRASH Trial,[21] which evaluated the effect of corticosteroids on head injury, or the CREATE-ECLA trial,[22] which evaluated the effect of the glucose-insulin-potassium (GIK) infusion in patients with myocardial infarction. Another good example is the Magpie trial, which assessed the effects of magnesium sulphate in approximately 10,000 women with pre-eclampsia, including women from Latin America, and resulted in a change of clinical practice.[23] Conducting regional RCTs will also promote the development of skills and infrastructure which will allow Latin America’s researchers to participate in international collaborations addressing these generic but locally relevant questions.

Finally, a further limitation of this report is that we only included RCTs, and it is possible that observational studies carried out in topics such as non communicable diseases and injuries are less likely to be published in the five leading medical journals which may favor RCTs.

What are the future challenges?

In this paper we only focused on published reports, yet it is widely recognized that only a small proportion of studies reach the publication stage. Unfortunately, at the moment, there is not any source with complete information about RCTs conducted available in Latin America. The World Health Organization is actively promoting an international initiative to develop registers of controlled trials.[24] In Latin America, the Colombian Branch of The Iberoamerican Cochrane Network developed the Latin American Ongoing Clinical Trials Register (LATINREC) which, when fully active, will represent a unique opportunity to obtain a detailed profile of the research conducted in the region.[25] The analysis of this register will confirm or not the gap found in this report and it will enable researchers and policy makers to draw an appropriate research profile of the region. It will be possible to identify duplication of work, inequitable funding of research, neglected diseases and other aspect such as source of funding and quality of design and reporting of clinical trials.[26]

In addition, editorial boards should not only avoid “bias against the diseases of poverty” but, in the context of the epidemiological transition occurring in developing regions, such as Latin America, they should also avoid the bias of what they consider diseases of poverty. This predisposition could partially explain why while Latin America experienced an increase of non-communicable diseases and injuries in the last 20 years, this epidemic was not mirrored by the RCTs published in the five leading medical journals.

Supporting Information

(0.03 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

Our special gratitude to Dr. Luis Gabriel Cuervo for his comments to an earlier version of this report and to Dr. Jocalyn Clark for her valuable editorial comments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: JJM is supported by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship (GR074833MA). The authors have no additional support or funding to report.

References

- 1.Global Forum for Health Research. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research; 2002. The 10/90 report on health research 2001–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton R. Medical journals: evidence of bias against the diseases of poverty. Lancet. 2003;361:712–713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton R. North and South: bridging the information gap. Lancet. 2000;355:2231–2236. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02414-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obuaya C-C. Reporting of research and health issues relevant to resource-poor countries in high-impact medical journals. Euro Science Edit. 2002;28:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rochon PA, Mashari A, Cohen A, Misra A, Laxer D, et al. Relation between randomized controlled trials published in leading general medical journals and the global burden of disease. CMAJ. 2004;170:1673–1677. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Patel V. Under-representation of developing countries in the research literature: ethical issues arising from a survey of five leading medical journals. BMC Medical Ethics. 2004;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakke P, Rigter H. Editors of medical journals: Who and from where. Scientometrics. 1985;1:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer A, Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Berdichevsky K, Villar J. Why is research from developing countries underrepresented in international health literature, and what can be done about it? Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:802–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keiser J, Utzinger J, Tanner M, Singer BH. Representation of authors and editors from countries with different human development indexes in the leading literature on tropical medicine: survey of current evidence. BMJ. 2004;328:1229–1232. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38069.518137.F6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Cambridge, Mass.: Published by the Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank. ; 1996. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perel P, Casas JP, Ortiz Z, Miranda JJ. Noncommunicable Diseases and Injuries in Latin America and the Caribbean: Time for Action. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3:e344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Library I, 2005, editor. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5 [updated May 2005]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glanville JM, Lefebvre C, Miles JN, Camosso-Stefinovic J. How to identify randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE: ten years on. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94:130–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Patel V. Under-representation of developing countries in the research literature: ethical issues arising from a survey of five leading medical journals. BMC Med Ethics. 2004;5:E5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isaakidis P, Swingler GH, Pienaar E, Volmink J, Ioannidis JP. Relation between burden of disease and randomised evidence in sub-Saharan Africa: survey of research. BMJ. 2002;324:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7339.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GESICA Investigators. Randomised trial of telephone intervention in chronic heart failure: DIAL trial. BMJ. 2005;331:425–. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38516.398067.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(2006) Chagas' disease–an epidemic that can no longer be ignored. Lancet. 2006;368:619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenyon S, Taylor DJ. The effect of the publication of a major clinical trial in a high impact journal on clinical practise: the ORACLE Trial experience. BJOG. 2002;109:1341–1343. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruzzi P. Non-drug industry funded research. BMJ. 2008;336:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39416.559942.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, Farrell B, Wasserberg J, et al. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1321–1328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Diaz R, Zhu J, Pais P, et al. Effect of glucose-insulin-potassium infusion on mortality in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the CREATE-ECLA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:437–446. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L, Farrell B, Moodley J, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877–1890. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulmezoglu AM, Pang T, Horton R, Dickersin K. WHO facilitates international collaboration in setting standards for clinical trial registration. Lancet. 2005;365:1829–1831. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reveiz L, Delgado MB, Urrutia G, Ortiz Z, Garcia Dieguez M, et al. The Latin American Ongoing Clinical Trial Register (LATINREC). Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;19:417–422. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892006000600014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegfried N, Clarke M, Volmink J. Randomised controlled trials in Africa of HIV and AIDS: descriptive study and spatial distribution. BMJ. 2005;331:742–. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(0.03 MB DOC)