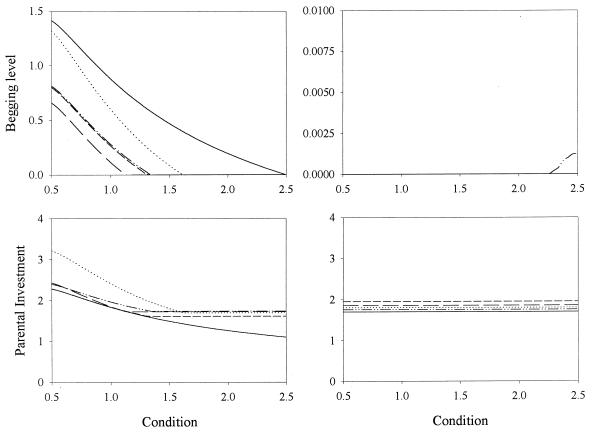

Figure 2.

Evolutionary dynamics of begging. Mean begging level (Upper) and parental investment (Lower) are plotted as a function of chick’s condition when the simulation was started at the signaling (Left) and nonsignaling (Right) equilibrium. Note that, because of the specific life history chosen for the simulation, the signaling equilibrium is given by  The solid line represents the initial condition and the others, values after 250,000, 500,000, 750,000 (dashed lines), and 1,000,000 (dotted lines) generations. The population had 1,225 territories. Young condition c was selected from a rectangular distribution (0.5–2.5) (2). Young and parental fitness (2) were calculated according to Fch = (1 − e−c⋅y) − V⋅x and Fp = 1 − γ⋅y, respectively (V = 0.1, γ = 0.08). Young dispersed at random. Signaling strategies could be any linear combination of the signaling equilibrium solution and polynomials of degree up to five. The genes coded for the coefficients of the terms, which could mutate with probability 0.001. In case of mutation, a single coefficient k was selected a random and a value (k + 0.05)⋅0.2⋅z was added to it, where z was a random variate chosen from a standard normal distribution. Mating and dispersal were random, irrespective of “distance” between territories. Qualitatively similar results were obtained with haploid and diploid individuals, when strategies were coded as neural networks or interpolation tables, and when mating and dispersal were restricted to neighboring territories.

The solid line represents the initial condition and the others, values after 250,000, 500,000, 750,000 (dashed lines), and 1,000,000 (dotted lines) generations. The population had 1,225 territories. Young condition c was selected from a rectangular distribution (0.5–2.5) (2). Young and parental fitness (2) were calculated according to Fch = (1 − e−c⋅y) − V⋅x and Fp = 1 − γ⋅y, respectively (V = 0.1, γ = 0.08). Young dispersed at random. Signaling strategies could be any linear combination of the signaling equilibrium solution and polynomials of degree up to five. The genes coded for the coefficients of the terms, which could mutate with probability 0.001. In case of mutation, a single coefficient k was selected a random and a value (k + 0.05)⋅0.2⋅z was added to it, where z was a random variate chosen from a standard normal distribution. Mating and dispersal were random, irrespective of “distance” between territories. Qualitatively similar results were obtained with haploid and diploid individuals, when strategies were coded as neural networks or interpolation tables, and when mating and dispersal were restricted to neighboring territories.