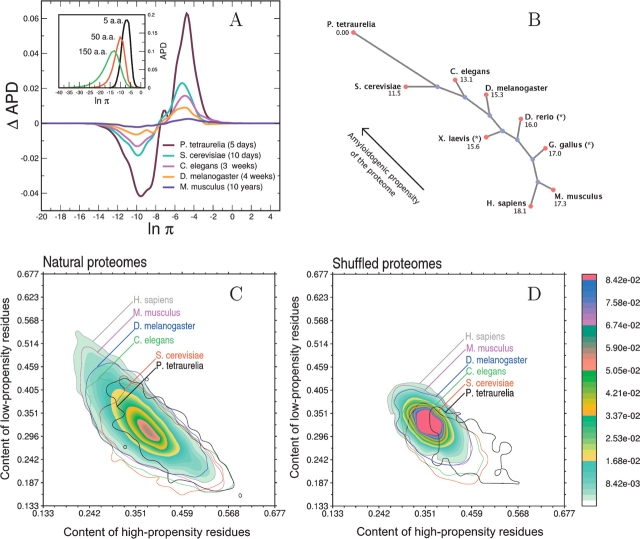

Figure 1.

(A) (Inset) Distribution of the number of human polypeptide sequences as a function of β-aggregation propensity (APD) at three different window sizes. (Main plot) APD differences with respect to H. sapiens for complete proteomes of M. musculus, D. melanogaster, C. elegans, S. cerevisiae, and P. tetraurelia (window size of five residues). Life spans of organisms are reported in parentheses. (B) Unrooted tree diagram derived from the APD deviation (Equation 4). The deviation is computed from P. tetraurelia as a reference and magnified by a factor of 1000. The arrow indicates that lower eukaryotes have more high-propensity and fewer low-propensity stretches. This diagram is built using Phylodraw with the Fitch and Margoliash (1967) clustering algorithm. Data labeled with * belong to incomplete proteomes. (Phylodraw is available at http://pearl.cs.pusan.ac.kr/phylodraw/.) (C) Normalized histogram of the number of proteins as a function of the content of residues enriched in low-propensity and high-propensity stretches. Global contours are shown for all proteomes by solid lines. Isofrequency regions are shown for the human proteome, where red color indicates the most populated area, while blue fading color indicates the least-populated areas. (D) Same as C for shuffled proteomes.