Abstract

The cyclic AMP (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) cascade plays a central role in β-cell proliferation and apoptosis. Here, we show that the incretin hormone glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) stimulates expression of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 gene in pancreatic β cells through a pathway involving AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), cAMP-responsive CREB coactivator 2 (TORC2), and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB). Stimulation of β-INS-1 (clone 832/13) cells with GIP resulted in increased Bcl-2 promoter activity. Analysis of the rat Bcl-2 promoter revealed two potential cAMP response elements, one of which (CRE-I [GTGACGTAC]) was shown, using mutagenesis and deletion analysis, to be functional. Subsequent studies established that GIP increased the nuclear localization of TORC2 and phosphorylation of CREB serine 133 through a pathway involving PKA activation and reduced AMPK phosphorylation. At the nuclear level, phospho-CREB and TORC2 were demonstrated to bind to CRE-I of the Bcl-2 promoter, and GIP treatment resulted in increases in their interaction. Furthermore, GIP-mediated cytoprotection was partially reversed by small interfering RNA-mediated reduction in BCL-2 or TORC2/CREB or by pharmacological activation of AMPK. The antiapoptotic effect of GIP in β cells is therefore partially mediated through a novel mode of transcriptional regulation of Bcl-2 involving cAMP/PKA/AMPK-dependent regulation of CREB/TORC2 activity.

The endocrine pancreas undergoes continual remodeling throughout life by processes involving neogenesis, cell replication, and apoptosis (1). In type I diabetes mellitus, an autoimmune disease, there is considerable evidence implicating apoptosis as the main mediator of islet β-cell death (37, 38). Type 2 diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia, chronic insulin resistance, and progressive pancreatic β-cell dysfunction, and recent studies have demonstrated that β-cell mass is reduced and the frequency of apoptosis is increased in human type 2 diabetic patients (5). In view of the increasing incidence of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, it is important to develop a clearer understanding of the cellular mechanisms involved in the activation of β-cell apoptosis and to identify agents that can slow or block this process.

Several cellular mechanisms may contribute to the loss of β-cell mass in type 2 diabetes, including free fatty acid-induced production of oxygen free radicals (O2−) and increased ceramide and nitric oxide (NO) synthesis (53), as well as down-regulation of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL-2 (49). BCL-2 is a member of a large family of apoptosis-regulating gene products that either facilitate cell survival (BCL-2, BCL-xL, and BCL-w) or promote cell death (BAX, BAK, and BAD) (8, 9). They function by selective protein-protein interaction, and the relative amounts of these proteins are critical determinants of the rates of pro- and antiapoptosis. In the fa/fa Zucker diabetic fatty rat, the onset of diabetes is caused by an excessive rate of β-cell death, rather than an inefficient replication capacity (49), and in this model maintenance of BCL-2 levels was shown to prevent the development of apoptosis resulting from lipotoxicity (49).

A number of prosurvival growth factors and hormones responsible for the maintenance of β-cell mass have been identified, including glucose (2, 41), insulin (42), prolactin (3), growth hormone (10), insulin-like growth factor 1 (24, 50), and the incretin hormones GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1) (12, 16) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) (13, 14, 33, 43, 51, 52). Long-acting analogs of GIP are considered to be potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (17, 21, 22) because of their insulinotropic actions. However, GIP also stimulates β-cell proliferation and promotes cell survival through actions linked to activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase modules (13, 14, 51, 52) and reduced expression of the proapoptotic bax gene via a pathway involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PKB)/forkhead transcription factor (Foxo1) signaling (33).

In the present study, we characterized the rat Bcl-2 promoter and identified a functional cyclic 5′-AMP (cAMP)-response element (CRE) that mediates GIP-stimulated increases in Bcl-2 gene expression in β-INS-1 (clone 832/13) cells. We have shown that GIP-stimulated phosphorylation of CREB (Ser133) and nuclear localization of cAMP-responsive CREB coactivator 2 (TORC2) are responsible for the trans activation of Bcl-2. Additionally, we demonstrated that AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates the nuclear localization of TORC2 and the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway is involved in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

INS-1 β cells (clone 832/13) were kindly provided by C. B. Newgard (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). INS-1 cells were cultured in 11 mM glucose RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma Laboratories, Natick, MA) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 unit/ml penicillin G-sodium, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Cell passages 45 to 75 were used. MIN6 β-cells were cultured in 25 mM high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 unit/ml penicillin G-sodium, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was extracted, and cDNA fragments were generated by reverse transcription. A total of 100 ng of cDNA was used in the real-time PCR to measure Bcl-2 expression, whereas 10 ng of cDNA was used in the Gapdh control PCR. The primer and probe sequences used for the amplification of Bcl-2 were as follows: forward primer, 5′-CTGAGTACCTGAACCGGCATC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-TGGCCCAGGTATGCACCCAGA-3′; probe, 5′-FAM-CCCCAGCATGCGACCTCTGTTTG-TAMRA-3′ (where FAM is 6-carboxyfluorescein and TAMRA is 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine). All reactions followed the typical sigmoidal reaction profile, and cycle threshold was used as a measurement of amplicon abundance.

Construction of Rat Bcl-2 promoter-luciferase plasmids.

The rat Bcl-2 gene promoter (1.7 kb) was cloned into the pGL3 vector (Promega Corp., Nepean, Ontario, Canada), and various deletion constructs were prepared by PCR with SacI and XhoI insertions for directed cloning. Site-directed mutant constructs were prepared using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All transfection plasmids were prepared using a Qiagen Plasmid Midi Kit (Valencia, CA).

Transient transfection and luciferase assay.

Cells were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/six-well plate. On the following day, transfection was performed with 2 μg of the indicated Bcl-2 promoter-luciferase constructs and 1 μg of pCMV-β-galactosidase plasmid (Clontech). Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) for 4 h according to the manufacturer's instructions. On the following day, cells were treated with GIP for the times indicated in the figures, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (Invitrogen), and lysed in 400 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activities were measured using a luciferase assay system (Promega) and normalized with β-galactosidase activities to correct for transfection efficiency. Relative luciferase activity is expressed as the normalized luciferase activity per microgram of protein.

Preparation of nuclear extracts.

Nuclear proteins were isolated as described by Schreiber et al. (47). Briefly, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and scraped with 200 μl of ice-cold buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Nonidet P40, and protease inhibitors). Following centrifugation, the resulting pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, and protease inhibitors) and incubated on ice for 10 min. After the clarification of the mixture by centrifugation, the supernatant (nuclear extract) was collected and subjected to Western analysis.

Western blot analysis.

Protein samples were separated on a 13% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Probing of the membranes was performed with phospho-CREB (serine 133), CREB, TORC2, β-actin, phospho-AMPK (threonine 172), AMPK, and BCL-2 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies.

Studies on the cellular localization and interaction between phospho-CREB and TORC2.

INS-1 cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight and stimulated for 30 min with 100 nM GIP or 10 μM forskolin in the presence or absence of 10 μM H-89 {N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide} added during a 1-h preincubation as well as during GIP or forskolin stimulation.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Following treatment, nuclear extracts were isolated and immunoprecipitated with anti-phospho-CREB (Ser133) antibody using protein A/G-agarose beads. The precipitated products were then resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed with anti-TORC2 antibody.

Confocal microscopy.

Following treatment, immunocytochemical staining was performed using phospho-CREB (serine 133) and TORC2 antibodies and visualized with Texas Red dye-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole) and imaged using a Zeiss laser scanning confocal microscope (Axioskop2). All imaging data were analyzed using the Northern Eclipse program (version 6).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

Following treatment, cells were fixed to isolate intact chromatin. Phospho-CREB and TORC2 were, respectively, immunoprecipitated from intact chromatin, using protein A/G-agarose beads and anti-phospho-CREB (Ser133) or anti-TORC2 antibody. Bound DNA was eluted and amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides flanking the CRE-I site of the rat Bcl-2 promoter.

RNA interference knockdown of CREB, TORC2, or BCL-2.

Since, in our hands, small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown in INS-1 cells is problematic and since well-characterized pools of siRNAs for mouse cells are commercially available, MIN6 β cells were utilized. Cells were transfected with a pool of 3 siRNAs for CREB, TORC2, or BCL-2 (sc-35111, sc-45833, or sc-29215, respectively; Santa Cruz) and incubated for 72 h. The level of reduction in CREB, TORC2, or BCL-2 protein expression was determined by Western blot hybridization using antibodies against phospho-CREB (serine 133), CREB, TORC2, BCL-2, and β-actin.

Studies on AMPK.

INS-1 cells (see Fig. 4) or MIN6 β cells (see Fig. 8) were treated with GIP (100 nM) in the presence or absence of AMPK inhibitor (40 μM compound C {6-[4-(2-iperidin-1-yl-ethoxy)-phenyl]-3-pyridin-4-yl-pyrrazolo[1,5-a]-pyrimidine}; EMD Bioscience, Brookfield, WI) or AMPK activator [5-(3-{4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethoxy]phenyl}propyl)furan-2-carboxylic acid (FPPF); 50 μM; EMD Bioscience]. AMPK inhibitor or activator was added to cells during a 1-h preincubation as well as during GIP stimulation.

FIG. 4.

GIP regulates the nuclear localization of TORC2 through a pathway involving activation of cAMP/PKA and decreased AMPK phosphorylation. (A) Concentration-dependent effect of GIP on phospho-AMPK (p-AMPK) Thr172. INS-1 cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight and treated for 30 min with the indicated concentrations of GIP. Total cellular extracts were isolated, and Western blot analyses were performed using antibody against phospho-AMPK (Thr172), AMPK and β-actin. (B) Effect of AMPK modulation on TORC2 activity. INS-1 cells were treated for 30 min with GIP (100 nM) in the presence or absence of AMPK inhibitor (compound C; 40 μM) or AMPK activator (50 μM FPPF). AMPK inhibitor or activator was added to cells during a 1-h preincubation as well as during GIP stimulation. Nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts were isolated from each sample, and Western blot analyses were performed. TORC2 blots are from nuclear extracts, and phospho-AMPK Thr172 and β-actin blots are from cytoplasmic extracts. (C) Effect of PKA inhibition on GIP-mediated decreases in phospho-AMPK Thr172. INS-1 cells were treated as described above and stimulated for 30 min with GIP (100 nM) or forskolin (10 μM) in the presence or absence of H-89. H-89 (10 μM) was added to cells during a 1-h preincubation as well as GIP stimulation. Cytoplasmic extracts were isolated from each sample, and Western blot analyses were performed. Western blots are representative of three replicates.

FIG. 8.

AMPK/TORC2/BCL-2 are involved in GIP-mediated β-cell survival. (A) Effects of AMPK/TORC2 modulation on GIP-mediated cytoprotection. MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for TORC2 (200 nM) or control siRNAs (200 nM) and incubated in the presence or absence of AMPK inhibitor (40 μM), AMPK activator (50 μM), and/or GIP (100 nM) under apoptotic conditions (with 1 μM thapsigargin for 8 h; serum free). Caspase-3 activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Effects of AMPK/TORC2 modulation on GIP-mediated trans activation of the Bcl-2 promoter. MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for TORC2 (200 nM) and the −1714 Bcl-2 promoter reporter construct, and Bcl-2 promoter activity assays were performed in the presence or absence of AMPK inhibitor or activator with the treatment of GIP (100 nM) or forskolin (10 μM). All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in duplicate. In panel A, control data are identical to those shown in Fig. 7D for the comparison. Significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls posthoc test. **, P < 0.05 versus control siRNA; ##, P < 0.05 versus control siRNA under apoptotic conditions; §§, P < 0.05 versus control siRNA under apoptotic conditions plus AMPK activator; ^, P < 0.05 versus TORC2 siRNA under apoptotic conditions; &&, P < 0.05 versus TORC2 siRNA under apoptotic conditions plus AMPK activator; ++, P < 0.05 versus TORC2 siRNA; and ••, P < 0.05 versus control siRNA plus AMPK activator.

Caspase-3 activity assay.

In studies examining the effect of BCL-2 knockdown on GIP-mediated cytoprotection, MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs (200 nM) for BCL-2, and apoptosis was induced by treatment with thapsigargin (1 μM) for 8 h under serum-free conditions, in the presence or absence of GIP (100 nM). For the studies designed to establish the involvement of AMPK and TORC2 in GIP-mediated cytoprotection, MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for TORC2, and caspase-3 activity was determined in the presence or absence of AMPK activator with cells subjected to the apoptosis-inducing conditions described above. Caspase-3 activity assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (standard, AMC [7-amino-4-methylcoumarin]; substrate, acetyl-DEVD-AMC; inhibitor, acetyl-DEVD-CHO) (Molecular Probes) and normalized to protein concentration.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean, with the number of individual experiments presented in the figure legends. Data were analyzed using the nonlinear regression analysis program PRISM (GraphPad, San Diego, CA), and significance was tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's multiple comparison test or the Newman-Keuls posthoc test (P < 0.05) as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

The effect of GIP on Bcl-2 gene expression.

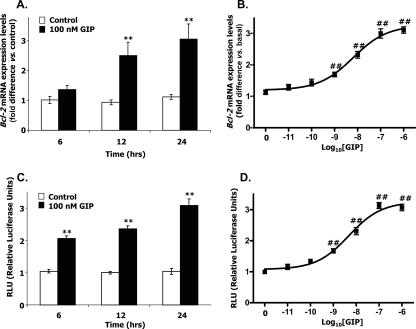

The effect of GIP on Bcl-2 gene transcription was studied using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Treatment of INS-1 cells with GIP (100 nM) for 24 h resulted in a threefold increase in Bcl-2 mRNA transcript levels compared to controls (Fig. 1A). Similar increases in rat Bcl-2 promoter activity were observed using a luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 1C). Both mRNA transcript levels (Fig. 1B) and Bcl-2 promoter activity (Fig. 1D) demonstrated concentration-dependent responses to GIP, with 50% effective concentration (EC50) values of 6.36 ± 0.19 nM and 5.87 ± 0.14 nM, respectively. The relative increases in Bcl-2 mRNA transcript levels in response to GIP treatment correlated well with the increases in Bcl-2 promoter activity with respect to time and concentration dependence, indicating that the increases in Bcl-2 mRNA levels probably resulted mainly from transcriptional activation of the Bcl-2 promoter.

FIG. 1.

GIP increases the expression of Bcl-2 in INS-1 cells. (A) Time course of GIP-induced Bcl-2 expression levels. INS-1 (clone 832/13) cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight, and GIP (100 nM) was added for the indicated periods of time. Total RNA was isolated from each sample, and real-time RT-PCR was performed to quantify Bcl-2 mRNA expression levels, shown as the relative difference from the control normalized to GAPDH expression levels. (B) Concentration response effect of GIP on Bcl-2 expression. INS-1 cells were treated as described above and treated with the indicated concentrations of GIP for 24 h. (C) Time course of GIP-induced Bcl-2 promoter activity. INS-1 cells were transfected with the −1714 Bcl-2 promoter reporter construct (2 μg) and pCMV β-galactosidase (1 μg) and serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight. Cells were then treated with 100 nM GIP for the indicated periods of time. The reporter activities are shown as the relative luciferase activity normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. (D) Concentration response effect of GIP on Bcl-2 promoter activity. INS-1 cells were transfected and treated as described above and incubated with the indicated concentrations of GIP for 24 h. All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate. Significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls posthoc test (A and C) or Dunnet's multiple comparison test (B and D). **, P < 0.01 versus basal level; ##, P < 0.01 versus control.

The effect of GIP on CREB/TORC2 modulation.

Mechanisms involved in the transcriptional activation of the Bcl-2 promoter by GIP treatment were studied next. Because functional studies on the rat Bcl-2 promoter had not been previously reported, we first analyzed rat Bcl-2 promoter sequences using the MatInspector (Abteling Genetik, Braunschweig, Germany) program. This revealed the presence of two potential CREs in addition to NF-κB, nuclear factor Y, activator protein 1, hypoxia-induced factor 1, stimulating protein 1 (SP-1), and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein consensus sequences. The presence of CREs in the rat Bcl-2 promoter implies that regulation of expression is linked to a signal transduction pathway involving a CREB-like protein. INS-1 cells were therefore treated with GIP (100 nM), and Western blot analyses were performed using antibodies against phospho-CREB Ser133. As shown in Fig. 2A, GIP stimulated phosphorylation of Ser133 CREB, with phosphorylation apparent 10 min after initiation of GIP treatment, thereafter gradually decreasing with time. Also evident is phosphorylation of a second member of the CREB family, activating transcription factor 1 (ATF-1) at Ser63, with which the anti-phospho-CREB antibody cross-reacts. ATF-1 was phosphorylated with kinetics similar to those of CREB. Subsequent studies demonstrated a GIP concentration dependence for phosphorylation of CREB and ATF-1, with EC50 values of 3.70 ± 0.13 nM and 4.54 ± 0.12 nM, respectively (Fig. 2B). The recent identification of TORC proteins that stimulate CREB transcriptional activity in the liver (35) prompted us to determine whether GIP regulation of TORC activity was involved in CREB-mediated Bcl-2 activation. As TORC2 has been demonstrated to be expressed most abundantly in insulinoma cells relative to the other family members, TORC1 and TORC3 (48), INS-1 cells were treated with GIP (100 nM), and Western blot analyses were performed on nuclear extracts using antibody against TORC2. As shown in Fig. 2C, GIP stimulated nuclear localization of TORC2, which was apparent 10 min after initiation of GIP treatment and was thereafter sustained to 120 min. Subsequent studies demonstrated a GIP concentration dependence for the nuclear localization of TORC2, with EC50 values of 0.69 ± 0.18 nM (Fig. 2D), i.e., with greater sensitivity to GIP than phosphorylation of CREB at Ser133.

FIG. 2.

GIP modulates CREB/TORC2 activity in INS-1 cells. (A) Time course of GIP-induced CREB phosphorylation. INS-1 cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight and treated for the indicated periods of time with 100 nM GIP. Nuclear extracts were isolated, and Western blot analyses were performed as described in Materials and Methods, using antibodies against phospho-CREB and CREB. (B) Concentration-dependent effect of GIP on CREB phosphorylation. INS-1 cells were treated for 10 min with the indicated concentrations of GIP, and Western blot analyses were performed. (C) Time course of GIP-induced nuclear localization of TORC2. INS-1 cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight and treated for the indicated periods of time with 100 nM GIP. Nuclear extracts were isolated, and Western blot analyses were performed as described in Materials and Methods using antibodies against TORC2. (D) Concentration response effect of GIP on nuclear localization of TORC2. INS-1 cells were treated for 30 min with the indicated concentrations of GIP, and Western blot analyses were performed. Western blots were quantified using densitometric analysis and are representative of three experiments. Significance was tested using ANOVA with Dunnet's multiple comparison test (**, P < 0.05 versus basal level). α, anti.

The involvement of cAMP/PKA in GIP activation of CREB/TORC2 and increased Bcl-2 expression.

In studies designed to examine the involvement of cAMP activation of PKA in GIP-mediated CREB phosphorylation, cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the selective PKA inhibitor, H-89 (Fig. 3A). Forskolin, a direct activator of adenylyl cyclase, was shown to mimic GIP-induced CREB activation (Fig. 3A). Phosphorylation of CREB in response to GIP was greatly reduced by H-89, and forskolin-induced CREB phosphorylation was also almost completely inhibited. Involvement of the cAMP/PKA pathway in GIP-mediated nuclear localization of TORC2 was next determined. As shown in Fig. 3B, both GIP and forskolin increased the nuclear localization of TORC2, and the responses were almost ablated by H-89 treatment. These results strongly support the involvement of cAMP/PKA in GIP-stimulated trafficking of TORC2 to the nucleus as well as phosphorylation of nuclear CREB. The participation of the cAMP/PKA pathway in GIP activation of Bcl-2 gene transcription was next examined using a promoter activity assay. Forskolin activated Bcl-2 promoter activity in a similar fashion to GIP, and both GIP- and forskolin-induced Bcl-2 promoter responses were significantly reduced by H-89 treatment (Fig. 3C). These responses correlated well with the results for CREB phosphorylation (Fig. 3A) and nuclear localization of TORC2 (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

The cAMP/PKA pathway is involved in GIP-mediated CREB/TORC2 modulation and Bcl-2 activation. (A) Effect of PKA inhibition on GIP-induced CREB phosphorylation. INS-1 cells were treated as described in Materials and Methods and stimulated for 10 min with 100 nM GIP or 10 μM forskolin in the presence or absence of H-89. H-89 (10 μM) was added to cells during a 1-h preincubation as well as during GIP stimulation. Nuclear extracts were isolated from each sample, and Western blot analyses were performed. (B) Effect of PKA inhibition on GIP-mediated nuclear localization of TORC2. INS-1 cells were treated as described in Materials and Methods and stimulated for 30 min with 100 nM GIP or 10 μM forskolin in the presence or absence of H-89 (10 μM). Nuclear extracts were isolated from each sample, and Western blot analyses were performed. (C) Effect of PKA inhibition on GIP-induced Bcl-2 promoter activity. INS-1 cells were cotransfected with the −1714 Bcl-2 promoter reporter construct (2 μg) and pCMV β-galactosidase (1 μg) and serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight. Cells were then stimulated for 24 h with GIP (100 nM) or forskolin (10 μM) in the presence or absence of H-89. H-89 was present during a 1-h preincubation and GIP stimulation. The reporter activities are shown as the relative luciferase activity normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate. Significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls posthoc test. **, P < 0.05 versus basal level; ##, P < 0.05 versus GIP; and §§, P < 0.05 versus forskolin. α, anti.

The effect of GIP on AMPK phosphorylation and the involvement of the cAMP/PKA/AMPK pathway for regulation of TORC2 activity.

The presence of a consensus AMPK phosphorylation site [XLXRXXSXXX(L/I), where X is any residue] in TORC2 led us to consider whether GIP may modulate TORC2 activity through regulation of AMPK phosphorylation. Subsequent studies demonstrated that GIP decreases phospho-AMPK Thr172 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). To determine whether AMPK can influence TORC2 activity in INS-1 cells, an AMPK inhibitor and an activator were employed. Treatment with the AMPK inhibitor compound C resulted in accumulation of TORC2 in the nucleus, whereas treatment with the AMPK activator FPPF resulted in substantial depletion of TORC2 from the nucleus (Fig. 4B). To examine the relationship between GIP-mediated decreases in phospho-AMPK Thr172 and the cAMP/PKA pathway, INS-1 cells were exposed to GIP or forskolin in the presence or absence of H-89 (Fig. 4C). Both agents reduced levels of phospho-AMPK Thr172 in an H-89-sensitive fashion (Fig. 4C). Overall, these results therefore strongly support a role for AMPK in regulating nuclear translocation of TORC2 in INS-1 cells and suggest that GIP can modulate the nuclear localization by reducing levels of phospho-AMPK Thr172 through a cAMP/PKA pathway.

Direct interaction between phospho-CREB and TORC2 in the nucleus.

The observation that GIP regulates both CREB phosphorylation and TORC2 localization led us to hypothesize that GIP activation should result in an increased interaction between the transcription factor CREB and the coactivator TORC2 in the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 5A, in coimmunoprecipitation experiments, direct protein-protein interaction between phospho-CREB Ser133 and TORC2 was observed in GIP-treated nuclear extracts. Forskolin mimicked the action of GIP, and H-89 completely ablated detectable interaction (Fig. 5A). When we further examined the effects of GIP or forskolin with or without H-89 on the subcellular distribution of phospho-CREB and TORC2 using confocal microscopy, similar results were observed. GIP and forskolin increased the nuclear localization of phospho-CREB and TORC2 in the nucleus, whereas H-89 blocked this process (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, phospho-CREB in an extranuclear site appears to be increased in cells treated with H-89. Taken together, PKA activation of phospho-CREB Ser133 and the increased CREB-TORC2 protein-protein interaction are likely to be important components of GIP-mediated effects on gene expression in INS-1 cells.

FIG. 5.

GIP increases protein-protein interaction between phospho-CREB and TORC2 in the nucleus. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation. INS-1 cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight and stimulated for 30 min with GIP (100 nM) or forskolin (10 μM) in the presence or absence of H-89 (10 μM). Nuclear extracts were isolated from each sample and immunoprecipitated (IP) with phospho-CREB (Ser133) followed by immunoblotting (IB) for TORC2. Input represents 1/10 of the total nuclear extract used in the Coimmunoprecipitation assay. (B) Confocal microscopy. INS-1 cells were treated as described above and fixed following stimulation with GIP (100 nM) or forskolin (10 μM) in the presence or absence of H-89 (10 μM). Immunocytochemical staining was performed using antibodies against phospho-CREB (Ser133; green) or TORC2 (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The scale bar indicates 20 μm, and all imaging data were analyzed using the Northern Eclipse program (version 6).

Identification of a functional CRE in the rat Bcl-2 promoter.

The functional CRE involved in GIP responsiveness of the Bcl-2 promoter was next identified. The rat Bcl-2 promoter contains two potential CREs, residing between −1287 and −1279 and between −1118 and −1110, that we have termed CRE-I and -II, respectively. CRE-I (GTGACGTAC) and the inverted CRE-II (GTGACGGCT) have 77.7% homology to the consensus CRE (GTGACGTCA) (substitutions are underlined). To identify the functional CRE(s), mutants of the rat Bcl-2 promoter were constructed serially deleted from the 5′ end of the −1714 to −1 fragment. As shown in Fig. 6A, the deletion from −1411 to −1211, containing CRE-I, most drastically decreased the GIP responsiveness. To evaluate further the functional significance of the CRE-I in trans activation of the Bcl-2 promoter following GIP treatment, site-specific mutations were introduced into CRE-I, and GIP responsiveness of these mutant constructs was determined using transient transfection analysis. Substitutions of three to four base pairs which flanked CRE-I (M1 to M4 CRE-I) decreased or abolished GIP responsiveness of these mutant constructs compared to the wild-type construct (WT CRE-I) (Fig. 6B). However, substitution of the final base pair (M5 CRE-I) did not disrupt GIP responsiveness of this mutant construct. CRE-I is therefore the cis-acting element of the Bcl-2 promoter involved in responses to GIP. Direct phospho-CREB/TORC2 binding to CRE-I in the Bcl-2 promoter was next determined by measuring occupancy of CRE-I using ChIP assays. GIP increased both phospho-CREB and TORC2 binding to CRE-I of Bcl-2 promoter; forskolin was similarly capable of increasing CREB/TORC2 binding. However, increased CREB and TORC2 binding to the Bcl-2 promoter was drastically reduced in cells treated with H-89 (Fig. 6C and D), supporting a role for GIP-mediated activation of PKA.

FIG. 6.

The rat Bcl-2 promoter contains a functional CRE. (A) A functional CRE was localized to one main region of Bcl-2 promoter by transient transfection analysis of serially deleted constructs. A schematic diagram of the Bcl-2 serial deletion reporter constructs and their potential CREB binding regions is presented. INS-1 cells were transfected with various serial deletion reporter constructs (2 μg) and pCMV β-galactosidase (1 μg) and starved overnight. Cells were then treated with 100 nM GIP for 24 h, and luciferase assays were performed. The reporter activities are shown as the relative luciferase activity normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. (B) Mutations in the CRE-I affect the GIP responsiveness of the rat Bcl-2 promoter. The sequences of WT and mutant CRE-I constructs are presented. All sequences of mutant CRE-I constructs were identical to the WT construct except for the indicated mutated sequences (underlined) in CRE-I. INS-1 cells were transfected with the WT construct (−1714 Bcl-2 promoter reporter construct; 2 μg) and pCMV β-galactosidase (1 μg) or mutated CRE-I constructs (M1 to M5 CRE-I; 2 μg) and pCMV β-galactosidase (1 μg). Cells were starved overnight and treated with 100 nM GIP for 24 h. Reporter activity is shown as the relative luciferase activity normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. (C and D) Representative gel picture of a ChIP assay for the binding of phospho-CREB (C) and TORC-2 (D) in the rat Bcl-2 promoter. INS-1 cells were serum starved in 3 mM glucose-RPMI medium containing 0.1% BSA overnight and stimulated for 10 min with 100 nM GIP or 10 μM forskolin in the presence or absence of H-89. H-89 (10 μM) was added to cells during a 1-h preincubation as well as during GIP stimulation. Phospho-CREB and TORC2 were immunoprecipitated from intact chromatin isolated from INS-1 cells using, respectively, anti-phospho-CREB (Ser133) and anti-TORC2 antibody. Precipitated DNA fragments were analyzed by PCR using primers flanking the CRE-I site in the Bcl-2 promoter. An isotype-matched immunoglobulin G was used as a negative control and 1% input (PCR product of 1/100 of the total isolated DNA used in the ChIP assay) was used as a positive control. All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in duplicate. Significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls posthoc test. **, P < 0.05 versus basal level. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Contribution of CREB/TORC2 as a positive trans-acting factor for Bcl-2 expression and the functional involvement of CREB/TORC2/BCL-2 in GIP-mediated cytoprotection.

To establish the importance of CREB and TORC2 in the regulation of Bcl-2 expression, RNA interference was employed. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, RNA interference-mediated knockdown resulted in specific concentration-dependent reductions in CREB, phospho-CREB, and TORC2 expression. Treatment with either CREB or TORC2 siRNA resulted in reductions in BCL-2 protein expression, and almost total knock-down was observed with the combination of CREB and TORC2 siRNAs. These results indicate that CREB and TORC2 are positive coordinate activators of Bcl-2 expression. The involvement of CREB and TORC2 in the antiapoptotic effects of GIP was examined by reducing their expression via siRNA treatment and determining caspase-3 responses to thapsigargin in the presence or absence of GIP. Thapsigargin induction of caspase-3 activity was potentiated by combined treatment with CREB and TORC2 siRNA. The ability of GIP to decrease responses to thapsigargin was reduced >50% by the combined siRNA treatment, establishing that CREB and TORC2 play key roles in GIP-mediated cytoprotection (Fig. 7C). Next, to further establish the contribution of BCL-2 to GIP-mediated cytoprotection, cells were treated with siRNA for BCL-2 (Fig. 7D), and caspase-3 activity was determined. As shown in Fig. 7E, similar responses were observed: reduction of BCL-2 expression by siRNA resulted in increased caspase-3 activity with thapsigargin treatment, and BCL-2 siRNA led to an attenuation of GIP effects on caspase-3 activity. Altogether, these results indicate a key involvement of CREB/TORC2/BCL-2 in GIP-mediated cytoprotection under thapsigargin-induced apoptotic conditions.

FIG. 7.

RNA interference-mediated suppression of CREB and TORC2 reduces Bcl-2 expression, and inhibition of BCL-2 expression results in attenuation of GIP-mediated cytoprotection. (A) Concentration-dependent effect of CREB siRNA on CREB/TORC2/BCL-2 expression. MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for CREB and incubated for 72 h. Western blot analyses were performed as described in Materials and Methods, using antibody against phospho-CREB (serine 133), CREB, TORC2, β-actin, and BCL-2. (B) Concentration-dependent effect of TORC2 siRNA on CREB/TORC2/BCL-2 expression. MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for TORC2, and Western blot analyses were performed. (C) Effects of CREB and TORC2 siRNAs on GIP-mediated cytoprotection. MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs each for CREB and TORC2 (100 nM for each) and treated with thapsigargin (1 μM) for 8 h in the presence or absence of GIP (100 nM) under serum-free conditions. Caspase-3 activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Concentration-dependent effect of BCL-2 siRNA on BCL-2 expression. MIN6 β cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for BCL-2, and Western blot analyses were performed using antibodies against β-actin and BCL-2. Phospho-CREB, CREB, and TORC2 blots were performed with nuclear extracts, and BCL-2 and β-actin blots were performed with cytoplasmic extracts. (E) Effects of BCL-2 siRNA on GIP-mediated cytoprotection. MIN6 β-cells were transfected with a pool of three siRNAs for BCL-2 (200 nM) and treated with thapsigargin as described in panel C. All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in duplicate, and Western blots are representative of three replicates. Significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls posthoc test. **, P < 0.05 versus control siRNA; ##, P < 0.05 versus control siRNA under apoptotic conditions; ^, P < 0.05 versus CREB plus TORC2 siRNAs under apoptotic conditions; §§, P < 0.05 versus BCL-2 siRNA under apoptotic conditions.

Contribution of AMPK/TORC2 to the β-cell prosurvival and Bcl-2 promoter activation effects of GIP.

Studies on caspase-3 responses to the modulation of AMPK/TORC2 provided further evidence for their functional involvement in the β-cell prosurvival effects of GIP. Thapsigargin alone increased caspase-3 activity approximately fourfold (Fig. 8A). Both AMPK activation with FPPF or siRNA-induced reduction in TORC2 expression potentiated responses to thapsigargin, resulting in approximately six- to sevenfold increases in caspase-3 activity, respectively (Fig. 8A). GIP-mediated protection was partially reversed by both treatments. Combined AMPK activation and reduction in TORC2 potentiated the effect of thapsigargin in an additive manner, with a ∼12-fold increase in caspase-3 activity and a further decrease in GIP responsiveness. This implies that both the expression level of TORC2 and the amount present in the dephosphorylated state are important factors in regulating apoptosis. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 8B, modulation of AMPK/TORC2 activity resulted in altered Bcl-2 promoter activity. Inhibition of AMPK increased basal promoter activity, but both GIP and forskolin treatment caused further activation. In contrast, reduction in TORC2 expression by siRNA or activation of AMPK resulted in significantly attenuated Bcl-2 promoter responses to GIP and forskolin, showing functional involvement of AMPK/TORC2 in GIP-mediated trans activation of Bcl-2.

DISCUSSION

Over the past few years considerable progress has been made in the identification and characterization of key proteins involved in the regulation of apoptosis. Among these, members of the Bcl-2 gene family are key modulators of both pro- and antiapoptotic events (8, 9). BCL-2 and the closely related BCL-xL and BCL-w have been shown to inhibit apoptosis resulting from cytokine deprivation and exposure to UV and γ radiation and cytotoxic drugs, as well as apoptosis-inducing gene products, such as Myc (9). BCL-2 is an integral membrane protein localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and nuclear envelope, but the pathways by which it acts have not been completely elucidated. Current proposals include inhibition of the proapoptotic actions of Bax through direct heterodimerization and indirect actions via modulation of intracellular calcium distribution (9). This results in protection against the damaging effects of cytochrome c released through the mitochondrial membrane (29), reactive oxygen species (54), and caspases (29). BCL-2 has been identified in pancreatic islets (23), and apoptosis in β-cell tumor lines is associated with changes in expression of the BCL-2 protein (40), implying that it is important for protecting pancreatic β cells against cell death. Further important observations support a central role for BCL-2 in β-cell survival: overexpression of BCL-2 in pancreatic islets (46) or the βTC-1 tumor cell line (27) protected the cells against apoptotic cell death and, in the Zucker diabetic fatty rat, maintenance of BCL-2 levels prevented the development of apoptosis resulting from lipotoxicity (49). However, little is known about the events that result in potentiation of the signaling capacity of BCL-2 during cellular responses to proapoptotic events. In the present study, we attempted to determine whether GIP plays a key regulatory role in transcriptional regulation of the Bcl-2 gene. To this end, we cloned the rat Bcl-2 promoter and, using the rodent β-INS-1 cell line, we identified a functional CRE, CRE-I (GTGACGTAC), in the promoter that exhibits high homology with the previously reported CRE (GTGACGTTA) (substitutions are underlined) in the human Bcl-2 promoter (56). GIP treatment increased levels of nuclear phospho-CREB Ser133 and TORC2 and enhanced direct protein-protein interactions between these two transcription factors (Fig. 2 and 5). In the confocal microscopy study, phospho-CREB in extranuclear sites appears to be increased in cells treated with H-89. The extranuclear localization of phospho-CREB is difficult to explain; however, cytoplasmic localization of phospho-CREB has been reported previously in several cell types, including granulosa cells (19) and cultured neurons (6), although the functional significance is obscure. A functional correlate of TORC2 translocation was provided by the demonstration of phospho-CREB/TORC2 selective binding to CRE-I of the rat Bcl-2 promoter (Fig. 6C and D), with deletion of the CRE-I region resulting in significantly decreased GIP responsiveness of the promoter (Fig. 6A). Moreover, nucleotide substitutions in the CRE-I region directly affected GIP responsiveness of the Bcl-2 promoter (Fig. 6B), demonstrating that CRE-I is a functional cis element for GIP-mediated Bcl-2 transcription. Additional evidence for such a role was provided by the fact that CRE-I-deleted mutants tended to show decreased basal activity compared to WT CRE-I (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, RNA interference-mediated knockdown of CREB and TORC2 resulted in significant reductions in BCL-2 protein expression, showing that CREB and TORC2 are functional trans-acting factors for the regulation of Bcl-2 (Fig. 7).

CREB plays a central role in cell survival pathways (7, 30, 39, 56). Cytokines were shown to down-regulate the active phosphorylated form of CREB in MIN6 β-cell lines, whereas overexpression of WT CREB by plasmid transfection or adenoviral infection led to protection against cytokine-induced apoptosis (28). During screening to identify modulators of CREB activity, a novel family of TORCs was identified (35). Although both CREB and TORC have been shown to enhance the expression of cAMP-responsive genes through direct interaction, the underlying molecular mechanisms are quite different. CREB phosphorylation at serine 133 is a requirement for binding to CBP. Initially, this covalent modification was attributed solely to PKA (18). However, subsequent studies have established that several kinases stimulated by growth factor-mediated signaling pathways can phosphorylate CREB at the same serine 133 site, leading to its activation (44, 45, 58). In contrast, nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of TORC is regulated by phosphorylation; TORC undergoes dephosphorylation in the cytoplasm and translocation into the nucleus in response to stimulation. Salt-inducible kinase, AMPK, and TORC phosphatase have been suggested to be involved in the regulation of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of TORC (35, 48). Among these, changes in cellular ATP levels seem to be uniquely recognized by AMPK, the founding member of this family (31, 36), with increases in the intracellular AMP/ATP ratio activating AMPK. AMPK activation can thus occur under environmental stress, and activation of AMPK has been shown to induce apoptosis in a pancreatic β-cell line (34). Recently, it has been demonstrated that agents capable of increasing intracellular cAMP levels in INS-1 β cells, such as GIP and forskolin, can reduce AMPK activity via inhibition of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase through activation of PKA (26). In the present study, GIP was shown to decrease levels of phospho-AMPK Thr172 (Fig. 4A), with associated changes in TORC2 localization (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, forskolin was shown to mimic the effects of GIP, whereas H-89 ablated the responses (Fig. 3B and 4C). Although H-89 has been shown to inhibit enzymatic activity of purified AMPK in an in vitro cell-free system (11), it is unlikely that, at the concentration used, direct inhibition played a major role in the current studies. It is not clear how the cAMP/PKA pathway reduces the levels of phospho-AMPK Thr172, but PKA has recently been shown to be an AMPK kinase acting on the AMPK Ser485 autophosphorylation site that plays a role in limiting AMPK activity, and H-89 was reported to decrease forskolin-stimulated phospho-AMPK Ser485/491 phosphorylation in INS-1 β cells (26). It was suggested that there may be a mechanism whereby Ser485 phosphorylation by PKA reduces subsequent phosphorylation of Thr172, thus inactivating AMPK in INS-1 β cells (26).

A critical functional role for GIP-mediated regulation of AMPK and TORC2 in the modulation of BCL-2 levels and β-cell survival was demonstrated in the studies on siRNA knockdown and thapsigargin-induced caspase-3 activation (Fig. 7 and 8). AMPK/TORC2 was involved in GIP-mediated transcriptional activation of Bcl-2 (Fig. 8B), and reduction of CREB/TORC2 expression, stimulation of AMPK activity, or reduced BCL-2 levels resulted in a marked reduction in the ability of GIP to reduce the activation of caspase-3 (Fig. 7 and 8A). A model showing the potential pathways involved in GIP regulation of CREB/TORC2 and Bcl-2 gene expression is presented in Fig. 9.

FIG. 9.

Proposed pathway by which GIP increases Bcl-2 transcription in pancreatic β cells. GIP binding to the G protein-coupled GIP receptor (GIPR) activates a stimulatory G protein (Gs), resulting in stimulation of adenylate cyclase (AC) and accumulation of cAMP. Active PKA catalytic subunits (C), released following cAMP binding to PKA regulatory subunits, enter the nucleus and phosphorylate CREB (white arrow). An associated decrease in phosphorylation and activity of AMPK is thought to result in dephosphorylation of TORC2, thus allowing increased translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Dashed lines indicate inhibitory pathways mediated by AMPK phosphorylation of TORC2, resulting in cytoplasmic retention, and PKA inhibition of AMPK, allowing TORC2 dephosphorylation. TORC2 complexes with phospho-CREB Ser133 in the nucleus and binds to CRE-I of the rat Bcl-2 promoter, thus turning on the transcriptional machinery for up-regulation of Bcl-2.

Antiapoptotic actions of a second major incretin hormone, GLP-1 (4, 12, 15, 16, 25, 55), have also been shown to involve increases in Bcl-2 mRNA and protein levels (4, 15). Evidence has been presented implicating both PKB (4, 25, 55) and PKA (25), with NF-κB acting as the final activator of Bcl-2 gene expression. NF-κB has been shown to activate human BCL-2 expression in the t(14;18) lymphoma cell line through CRE and SP-1 binding sites (20). Although the majority of NF-κB activity was found to be mediated through CRE, there was also cooperative interaction with the 5′ SP-1 binding site, located within 50 bp upstream of CRE, and direct interaction between NF-κB and a CREB family member has been demonstrated (32, 57). In our sequence-based analysis of the rat Bcl-2 promoter using the MatInspector program, there was a potential SP-1 binding site (5′-CGGCGGGCGGGCGCT-3′) located at 50 bp upstream of the functional CRE-I (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, a potential NF-κB binding site (5′-GGGGGAACTTCGTAG-3′) was also present downstream of CRE-II; however, this site does not seem to be functional because its absence did not significantly affect GIP responsiveness of the rat Bcl-2 promoter (Fig. 6A). There is, therefore, the potential for GIP-mediated cooperation among NF-κB and CREB/TORC2/CBP for trans activation of rat Bcl-2 through CRE-I and the 5′ SP-1 site. Finally, in view of the increasing incidence of diabetes, it will be intriguing to determine how the various key players in the regulatory networks interact in the incretin-mediated regulation of pro- and antiapoptotic genes.

Acknowledgments

These studies were generously supported by funding to C.H.S.M. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant 590007) and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation.

We thank C. B. Newgard (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC) for kindly providing us with INS-1 cells (clone 832/13).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonner-Weir, S. 2001. Beta-cell turnover: its assessment and implications. Diabetes 50(Suppl. 1)S20-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner-Weir, S., D. Deery, J. L. Leahy, and G. C. Weir. 1989. Compensatory growth of pancreatic beta-cells in adult rats after short-term glucose infusion. Diabetes 3849-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brelje, T. C., J. A. Parsons, and R. L. Sorenson. 1994. Regulation of islet beta-cell proliferation by prolactin in rat islets. Diabetes 43263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buteau, J., W. El-Assaad, C. J. Rhodes, L. Rosenberg, E. Joly, and M. Prentki. 2004. Glucagon-like peptide-1 prevents beta cell glucolipotoxicity. Diabetologia 47806-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler, A. E., J. Janson, S. Bonner-Weir, R. Ritzel, R. A. Rizza, and P. C. Butler. 2003. β-Cell deficit and increased β-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalovich, E. M., J. H. Zhu, J. Caltagarone, R. Bowser, and C. T. Chu. 2006. Functional repression of cAMP response element in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28117870-17881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciani, E., S. Guidi, G. Della Valle, G. Perini, R. Bartesaghi, and A. Contestabile. 2002. Nitric oxide protects neuroblastoma cells from apoptosis induced by serum deprivation through cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 27749896-49902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cory, S., and J. M. Adams. 2002. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cory, S., D. C. Huang, and J. M. Adams. 2003. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene 228590-8607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cousin, S. P., S. R. Hugl, M. G. Jr. Myers, M. F. White, A. Reifel-Miller, and C. J. Rhodes. 1999. Stimulation of pancreatic beta-cell proliferation by growth hormone is glucose-dependent: signal transduction via Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) with no crosstalk to insulin receptor substrate-mediated mitogenic signaling. Biochem. J. 15649-658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies, S. P., H. Reddy, M. Caivano, and P. Cohen. 2000. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem. J. 35195-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drucker, D. J. 2003. Glucagon-like peptides: regulators of cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Mol. Endocrinol. 17161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehses, J. A., S. L. Pelech, R. A. Pederson, and C. H. S. McIntosh. 2002. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide activates the Raf-Mek1/2-ERK1/2 module via a cyclic AMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase/Rap1-mediated pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 27737088-37097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehses, J. A., V. R. Casilla, T. Doty, J. A. Pospisilik, K. D. Winter, H. U. Demuth, R. A. Pederson, and C. H. S. McIntosh. 2003. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide promotes beta-(INS-1) cell survival via cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated caspase-3 inhibition and regulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology 1444433-4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farilla, L., A. Bulotta, B. Hirschberg, Calzi. Li, N. Khoury, H. Noushmehr, C. Bertolotto, U. Di Mario, D. M. Harlan, and R. Perfetti. 2003. Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibits cell apoptosis and improves glucose responsiveness of freshly isolated human islets. Endocrinology 1445149-5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farilla, L., H. Hui, C. Bertolotto, E. Kang, A. Bulotta, U. Di Mario, and R. Perfetti. 2002. Glucagon-like peptide-1 promotes islet cell growth and inhibits apoptosis in Zucker diabetic rats. Endocrinology 1434397-4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gault, V. A., F. P. O'Harte, and P. R. Flatt. 2003. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP): anti-diabetic and anti-obesity potential? Neuropeptides 37253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez, G. A., and M. R. Montminy. 1989. Cyclic AMP stimulates somatostatin gene transcription by phosphorylation of CREB at serine 133. Cell 59675-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Robayna, I. J., T. N. Alliston, P. Buse, G. L. Firestone, and J. S. Richards. 1999. Functional and subcellular changes in the A-kinase-signaling pathway: relation to aromatase and Sgk expression during the transition of granulosa cells to luteal cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 131318-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckman, C. A., J. W. Mehew, and L. M. Boxer. 2002. NF-κB activates Bcl-2 expression in t(14;18) lymphoma cells. Oncogene 213898-3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinke, S. A., R. W. Gelling, R. A. Pederson, S. Manhart, C. Nian, H. U. Demuth, and C. H. S. McIntosh. 2002. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV-resistant [d-Ala2]glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) improves glucose tolerance in normal and obese diabetic rats. Diabetes 51652-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinke, S. A., S. Manhart, K. Kuhn-Wache, C. Nian, H. U. Demuth, R. A. Pederson, and C. H. S. McIntosh. 2004. [Ser2]- and [Ser(P)2]incretin analogs: comparison of dipeptidyl peptidase IV resistance and biological activities in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2793998-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hockenbery, D. M., M. Zutter, W. Hickey, M. Nahm, and S. J. Korsmeyer. 1991. BCL2 protein is topographically restricted in tissues characterized by apoptotic cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 886961-6965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hugl, S. R., M. F. White, and C. J. Rhodes. 1998. Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)-stimulated pancreatic beta-cell growth is glucose-dependent. Synergistic activation of insulin receptor substrate-mediated signal transduction pathways by glucose and IGF-I in INS-1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27317771-17779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui, H., A. Nourparvar, X. Zhao, and R. Perfetti. 2003. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits apoptosis of insulin-secreting cells via a cyclic 5′-adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A- and a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. Endocrinology 1441444-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurley, R. L., L. K. Barre, S. D. Wood, K. A. Anderson, B. E. Kemp, A. R. Means, and L. A. Witters. 2006. Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by multisite phosphorylation in response to agents that elevate cellular cAMP. J. Biol. Chem. 28136662-36672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwahashi, H., T. Hanafusa, Y. Eguchi, H. Nakajima, J. Miyagawa, N. Itoh, K. Tomita, M. Namba, M. Kuwajima, T. Noguchi, Y. Tsujimoto, and Y. Matsuzawa. 1996. Cytokine-induced apoptotic cell death in a mouse pancreatic beta-cell line: inhibition by Bcl-2. Diabetologia 39530-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jambal, P., S. Masterson, A. Nesterova, R. Bouchard, B. Bergman, J. C. Hutton, L. M. Boxer, J. E. Reusch, and S. Pugazhenthi. 2003. Cytokine-mediated down-regulation of the transcription factor cAMP-response element-binding protein in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27823055-23065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang, J. H., and Y. J. Surh. 2003. Potentiation of cellular antioxidant capacity by Bcl-2: implications for its antiapoptotic function. Biochem. Pharmacol. 661371-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jhala, U. S., G. Canettieri, R. A. Screaton, R. N. Kulkarni, S. Krajewski, J. Reed, J. Walker, X. Lin, M. White, and M. Montminy. 2003. cAMP promotes pancreatic beta-cell survival via CREB-mediated induction of IRS2. Genes Dev. 171575-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahn, B. B., T. Alquier, D. Carling, and D. G. Hardie. 2005. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 115-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaszubska, W., R. Hooft van Huijsduijnen, P. Ghersa, A. M. DeRaemy-Schenk, B. P. Chen, T. Hai, J. F. DeLamarter, and J. Whelan. 1993. Cyclic AMP-independent ATF family members interact with NF-κB and function in the activation of the E-selectin promoter in response to cytokines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 137180-7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, S. J., K. Winter, C. Nian, M. Tsuneoka, Y. Koda, and C. H. S. McIntosh. 2005. GIP stimulation of pancreatic beta-cell survival is dependent upon phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/protein kinase B (PKB) signaling, inactivation of the forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 and downregulation of bax expression. J. Biol. Chem. 28022297-22307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim, W. H., J. W. Lee, Y. H. Suh, H. J. Lee, S. H. Lee, Y. K. Oh, B. Gao, and M. H. Jung. 2007. AICAR potentiates ROS production induced by chronic high glucose: roles of AMPK in pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Cell Signal. 19791-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koo, S. H., L. Flechner, L. Qi, X. Zhang, R. A. Screaton, S. Jeffries, S. Hedrick, W. Xu, F. Boussouar, P. Brindle, H. Takemori, and M. Montminy. 2005. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature 4371109-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lizcano, J. M., O. Goransson, R. Toth, M. Deak, N. A. Morrice, J. Boudeau, S. A. Hawley, L. Udd, T. P. Makela, D. G. Hardie, and D. R. Alessi. 2004. LKB1 is a master kinase that activates 13 kinases of the AMPK subfamily, including MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J. 23833-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandrup-Poulsen, T. 2001. Beta-cell apoptosis: stimuli and signaling. Diabetes 50(Suppl. 1)S58-S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mauricio, D., and T. Mandrup-Poulsen. 1998. Apoptosis and the pathogenesis of IDDM: a question of life and death. Diabetes 471537-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehrhof, F. B., F. U. Muller, M. W. Bergmann, P. Li, Y. Wang, W. Schmitz, R. Dietz, and R. von Harsdorf. 2001. In cardiomyocyte hypoxia, insulin-like growth factor-I-induced antiapoptotic signaling requires phosphatidylinositol-3-OH-kinase-dependent and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent activation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein. Circulation 1042088-2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizuno, N., H. Yoshitomi, H. Ishida, H. Kuromi, J. Kawaki, Y. Seino, and S. Seino. 1998. Altered Bcl-2 and Bax expression and intracellular Ca2+ signaling in apoptosis of pancreatic cells and the impairment of glucose-induced insulin secretion. Endocrinology 1391429-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen, J. H. 1985. Growth and function of the pancreatic beta cell in vitro: effects of glucose, hormones and serum factors on mouse, rat and human pancreatic islets in organ culture. Acta Endocrinol. Suppl. (Copenh). 2661-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paris, M., C. Bernard-Kargar, M. F. Berthault, L. Bouwens, and A. Ktorza. 2003. Specific and combined effects of insulin and glucose on functional pancreatic beta-cell mass in vivo in adult rats. Endocrinology 1442717-2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pederson, R. A. 1994. Gastric inhibitory peptide, p. 217-259. In J. Walsh and G. Dockray (ed.), Gut peptides: biochemistry and physiology. Raven, New York, NY.

- 44.Pugazhenthi, S., A. Nesterova, C. Sable, K. A. Heidenreich, L. M. Boxer, L. E. Heasley, and J. E. Reusch. 2000. Akt/protein kinase B up-regulates Bcl-2 expression through cAMP-response element-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 27510761-10766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pugazhenthi, S., T. Boras, D. O'Connor, M. K. Meintzer, K. A. Heidenreich, and J. E. Reusch. 1999. Insulin-like growth factor I-mediated activation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein in PC12 cells. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2742829-2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabinovitch, A., W. Suarez-Pinzon, K. Strynadka, Q. Ju, D. Edelstein, M. Brownlee, G. S. Korbutt, and R. V. Rajotte. 1999. Transfection of human pancreatic islets with an anti-apoptotic gene (Bcl-2) protects beta-cells from cytokine-induced destruction. Diabetes 481223-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schreiber, E., P. Matthias, M. M. Muller, and W. Schaffner. 1989. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with “mini-extracts,” prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 176419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Screaton, R. A., M. D. Conkright, Y. Katoh, J. L. Best, G. Canettieri, S. Jeffries, E. Guzman, S. Niessen, J. R. Yates III, H. Takemori, M. Okamoto, and M. Montminy. 2004. The CREB coactivator TORC2 functions as a calcium- and cAMP-sensitive coincidence detector. Cell 11961-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimabukuro, M., M. Y. Wang, Y. T. Zhou, C. B. Newgard, and R. H. Unger. 1998. Protection against lipoapoptosis of beta cells through leptin-dependent maintenance of Bcl-2 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 959558-9561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, F. E., K. M. Rosen, L. Villa-Komaroff, G. C. Weir, and S. Bonner-Weir. 1991. Enhanced insulin-like growth factor I gene expression in regenerating rat pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 886152-6156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trümper, A., K. Trümper, and D. Hörsch. 2002. Mechanisms of mitogenic and anti-apoptotic signaling by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in β(INS-1)-cells. J. Endocrinol. 174233-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trümper, A., K. Trümper, H. Trusheim, R. Arnold, B. Göke, and D. Hörsch. 2001. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide is a growth factor for β(INS-1) cells by pleiotropic signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 151559-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unger, R. H., and L. Orci. 2002. Lipoapoptosis: its mechanism and its diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1585202-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vander Heiden, M. G., and C. B. Thompson. 1999. Bcl-2 proteins: regulators of apoptosis or of mitochondrial homeostasis? Nat. Cell Biol. 1E209-E216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, Q., L. Li, E. Xu, V. Wong, C. Rhodes, and P. L. Brubaker. 2004. Glucagon-like peptide-1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis via activation of protein kinase B in pancreatic INS-1 beta cells. Diabetologia 47478-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson, B. E., E. Mochon, and L. M. Boxer. 1996. Induction of Bcl-2 expression by phosphorylated CREB proteins during B-cell activation and rescue from apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 165546-5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiang, H., J. Wang, and L. M. Boxer. 2006. The role of the cAMP-response element in the Bcl-2 promoter in the regulation of endogenous Bcl-2 expression and apoptosis in murine B cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 268599-8606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xing, J., J. M. Kornhauser, Z. Xia, E. A. Thiele, and M. E. Greenberg. 1998. Nerve growth factor activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways to stimulate CREB serine 133 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 181946-1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]