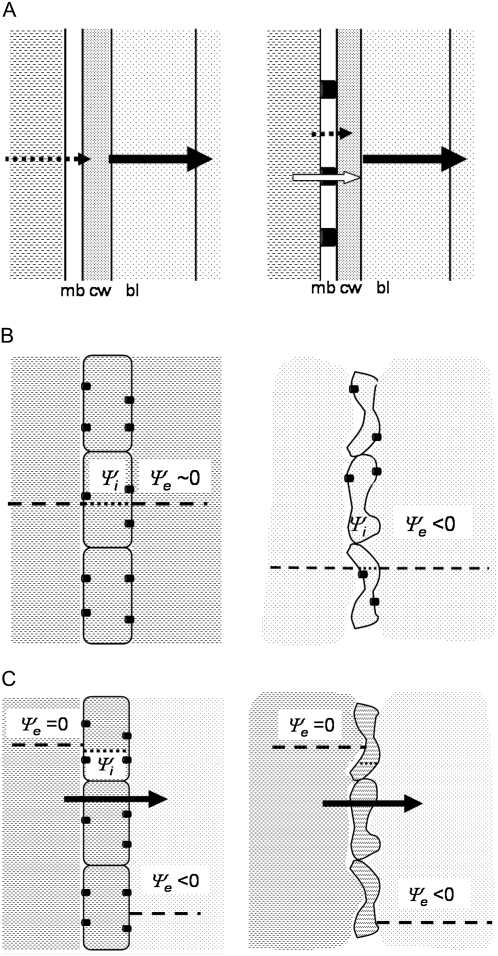

Figure 8.

Schematic drawing of transmembrane and transcellular transpiration flow (side view). A, Transpiration from a cell surface. The magnitude of the transmembrane flow (black arrow) is mainly determined by the resistance in the boundary layer (left drawing). Opening AQPs adds a pathway to water across the membrane, but does not modify the magnitude of the transpiration flow (right drawing). mb, Membrane; cw, cell wall; bl, boundary layer; dotted arrow, flow through the lipid bilayer; white arrow, flow through AQPs. B, When both sides of a cell are in contact with a water potential Ψe in the external medium, the cell water potential Ψi reaches an equilibrium value Ψi = Ψe. If Ψe ∼ 0 (left) the cell remains turgid; if Ψe is too negative (right) the cell becomes wilted. C, Transcellular transpiration flow from a cell with one side facing liquid water (Ψe ∼ 0), the other side facing the air. When the transpiration flow (black arrow) is not too high (medium stress), AQPs can keep Ψi close to zero by reducing the resistance of the membrane (left). For the same transpiration flow, if AQPs are removed from the membrane (right), the increase in resistance can produce a more dangerous drop in Ψi.