Abstract

Application of recombinant DNA technology and electrophysiology to the study of amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels has resulted in an enormous increase in the understanding of the structure–function relationships of these channels. Moreover, this knowledge has permitted the elucidation of the physiological roles of these ion channels in cellular processes as diverse as transepithelial salt and water movement, taste perception, volume regulation, nociception, neuronal function, mechanosensation, and even defaecation. Although members of this ever-growing superfamily of ion channels (the Deg/ENaC superfamily) share little amino acid identity, they are all organized similarly, namely, two short N- and C-termini, two short membrane-spanning segments, and a very large extracellular loop domain. In this brief Topical Review, we discuss the structural features of each domain of this Deg/ENaC superfamily and, using ENaC as a model, show how each domain relates to overall channel function.

Amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels are essential control elements for the regulation of Na+ transport into cells and across epithelia. These channels are ubiquitous; they are not only present in numerous epithelia, but also in endothelia, brain, osteoblasts, keratinocytes, taste cells and lymphocytes. As a class, amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels show a wide range of electrophysiological properties (Benos, 1989; Benos et al. 1995, 1996; Barbry & Hofman, 1997; Garty & Palmer, 1997; Fyfe et al. 1998). Moreover, primary malfunctions of these channels underlie the pathophysiology of several important human genetic diseases such as salt-sensitive hypertension (Liddle's syndrome) and pseudohypoaldosteronism type I (PHA-1). Interactions with other ion channels, most notably cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), may also have important implications for human disease, i.e. cystic fibrosis (Schwiebert et al. 1999). In addition to their central role in Na+ homeostasis and extracellular volume control, amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels are particularly important in the period just before birth where the fetal lung must convert from a secretory to a re-absorptive organ (O'Brodovich, 1991; Hummler et al. 1996). Moreover, these channels are prominently involved in the clearance of fluid from the airway and alveolar surfaces in the adult in order to maintain a minimal diffusion distance for efficient gas exchange (Matalon et al. 1996; Jain et al. 1999).

This brief commentary will focus on the structure–function relationships of amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels, specifically the epithelial Na+ channels, or ENaCs. This channel consists of three non-identical, but homologous subunits, α-, β- and γ-ENaC. Table 1 summarizes the amino acid lengths of the known α-, β-, and γ-ENaC orthologues (range 632–698 amino acids). Expression of the subunits in heterologous cells, most notably Xenopus oocytes and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, showed that amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents could be produced by the α subunit alone, and that co-expression with the β and γ subunits enhanced this expression by over 100-fold (Canessa et al. 1994a; Ishikawa et al. 1998). These basic findings, namely, that α-ENaC by itself could form bona fide amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels and β- and/or γ-ENaC could not, were validated in planar lipid bilayer studies (Ismailov et al. 1996).

Table 1.

Total number of amino acids comprising the known members of the ENaC family branch

| Orthologue name | Total amino acids |

|---|---|

| α-rENaC | 698 |

| α-hENaC | 669 |

| α-bENaC | 650 |

| α-mENaC | 699 |

| α-cENaC | 637 |

| α-xENaC | 632 |

| δ-hENaC | 638 |

| β-rENaC | 638 |

| β-hENaC | 640 |

| β-mENaC | 638 |

| β1-xENaC | 647 |

| β2-xENaC | 646 |

| γ-rENaC | 650 |

| γ-hENaC | 649 |

| γ-mENaC | 655 |

| γ1-xENaC | 660 |

| γ2-xENaC | 663 |

The α subunit of ENaC was first identified by Canessa et al. (1993) and Lingueglia et al. (1993) in expression cloning studies, followed the next year by the cloning of the β and γ subunits (Canessa et al. 1994a). To date, over 30 members of this ever-growing superfamily of ion channels have been identified, and they have divided into five branches: degenerins, the FMRFamide (phenylalanine-methionine-arginine-phenylalanine)-activated Na+ channel (FaNaCh), brain sodium channels (BNaCs), Pickpocket/Ripped pocket (PPK/RPK), and the ENaCs (Fig. 1). The first identified members of this superfamily were the genes required for touch or mechanosensitivity (Mec genes) and degeneration (Deg genes) of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans (Chalfie & Wolinsky, 1990; Driscoll & Chalfie, 1991). Together, these gene products are termed degenerins. Alterations in the proteins coded by these genes (for example, by deletion mutations) result in either a loss of touch sensitivity in the worms or, in the case of gain-of-function mutations, swelling and subsequent neuronal degeneration. Due to the similarity in overall topography between the degenerins and ENaC, it was hypothesized that the degenerins coded for ion channels. This hypothesis was supported by experiments in which chimeric ENaC-degenerin proteins displayed ion channel activity (Waldmann et al. 1995). It was only recently that Garcia-Anoveros et al. (1998) demonstrated directly that the degenerin UNC-105 forms an ion channel.

Figure 1. Major branches of the Deg/ENaC superfamily.

Another branch of this superfamily includes FaNaCh, cloned from the neurons of the snail Helix aspersa (Lingueglia et al. 1995). This amiloride-sensitive ion channel is activated by the peptide FMRFamide (Green et al. 1994). The BNaC branch consists of three genes, BNaC1 (mDeg), BNaC2 (acid-sensing ion channel, ASIC) and DRASIC (dorsal root acid-sensing ion channel), which are expressed exclusively in mammalian brain and neurons (Price et al. 1996; Waldmann et al. 1996; Garcia-Anoveros et al. 1997; Bassilana et al. 1997; Waldmann et al. 1997a, b; Lingueglia et al. 1997; Waldmann & Lazdunski, 1998; Babinski et al. 1999). Most recently, several new Deg/ENaC members have been discovered in Drosophila, the ripped pocket (RPK) and dGNaC1 genes that are expressed early in development and in testes, and the pickpocket (PPK) and dmdNaC1 genes that are found in late stage and early larval mechanosensory dendritic neurons (Adams et al. 1998; Darboux et al. 1998a, b). Both amiloride and gadolinium, agents that block mechanosensitivity in vivo, inhibit RPK channels. While PPK did not form channels on its own, it was able to reduce BNaC-associated currents when simultaneously expressed in oocytes (Adams et al. 1998).

All members of the Deg/ENaC superfamily have the predicted membrane topology depicted in Fig. 2. We use the α-, β- and γ-ENaC subunits as examples (Canessa et al. 1994b; Renard et al. 1994; Snyder et al. 1994). These channels are of the two-pass type, meaning that there are two membrane-spanning regions, similar to the inwardly rectifying K+ channel family (North, 1996). Each subunit can be defined in terms of four distinct domains: the cytoplasmic N-terminus (domain I), the large extracellular loop (domain II), the two short hydrophobic segments (domain III), and the cytoplasmic C-terminus (domain IV). Although, structure-activity studies of this channel have only just commenced, enough information is available to begin to assign specific functions to each of these domains. It is our intent to summarize what is known about each of these channel domains, and identify what information needs to be obtained in order to develop a comprehensive picture of the mechanism of operation of these important ion channels.

Figure 2. Membrane topology of each subunit (α-, β- and γ-) ENaC.

M1 and M2 indicate helical transmembrane domains; CRD1 and CRD2 indicate cysteine-rich domains; glycosylation sites are indicated (6 on α-ENaC, 12 on β-ENaC, and 5 on γ-ENaC). The filled bar within CRD1 of α-ENaC indicates the relative position of a 6 amino acid region known to bind amiloride (Kieber-Emmons et al. 1999).

The N-terminal, cytoplasmic region of ENaC (domain I)

Recent studies suggest that the cytoplasmic, N-terminus of ENaC participates in many key functions including subunit assembly, gating, and endocytic retrieval and degradation (Adams et al. 1997; Grunder et al. 1997; Horisberger, 1998; Prince & Welsh, 1998). However, a complete understanding of the function of the N-terminus of any ENaC subunit is not available. Inspection of Fig. 3 reveals that there is considerable sequence homology in the cytoplasmic, N-terminus of α-, β- and γ-ENaC subunits (Lingueglia et al. 1993; Canessa et al. 1994a, b; Fyfe et al. 1998). Sequence analysis reveals that the N-terminus contains two potential sites for myristoylation, but no consensus sites for phosphorylation or other post-translational modifications. One protein motif, KGDK (47–50 in α-rENaC), present in rat, human, bovine and mouse α-ENaC (Thomas et al. 1998) may be involved in the endocytic retrieval of ENaC from the plasma membrane. In addition, there are several amino acids that are highly conserved among ENaC subunits and species. These include lysine residues, which play a role in ubiquitination, endocytosis, and channel degradation, at K47, K50 and K108 (in α-rENaC) (Staub et al. 1997; Goulet et al. 1998). Moreover, there are five amino acids (92–96 in α-rENaC), including a histidine (H94 in α-rENaC) and a glycine (G95 in α-rENaC) that are fully conserved from the nematode to mammalian sequences, that have been implicated in channel gating. Although it has been suggested that a hydrophobic region in the N-terminus may form part of the channel pore (Canessa, 1996), recent observations suggest that this hydrophobic region is unlikely to contribute to the pore; rather, it may influence channel gating (Grunder et al. 1997; Berdiev et al. 1998).

Figure 3. Amino acid alignment of α(δ)-, β- and γ-ENaC in the N-terminal domain.

To begin to elucidate the function of the cytoplasmic, N-terminus of the rat epithelial sodium channel (rENaC), we constructed a series of truncated cDNAs and expressed the cRNAs in Xenopus oocytes (Chalfant et al. 1998; Chalfant et al. 1999a, b). Amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents (INa) were measured by the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. Deletion of the entire cytoplasmic, N-terminus of α-, β-, or γ-rENaC completely eliminated INa when any mutant subunit replaced its wild-type (WT) subunit. Thus, the cytoplasmic N-terminus of α-, β- and γ-rENaC is required for functional channel expression in oocytes. When co-expressed with wild-type α-, β- and γ-rENaC subunits, N-terminal mutants of each rENaC subunit dramatically reduced INa. Thus, N-terminal-truncated rENaC subunits (ΔN) act as dominant negative mutants that displace WT subunits from the multimeric ion channel complex. The failure of ΔN-rENaC subunits to support maximum channel activity suggests that the N-terminus is required for subunit assembly and delivery to the plasma membrane. Alternatively, or in addition, it is possible that ΔN-rENaC subunits interact with wild-type subunits and move to the membrane; however, the N-terminus of each subunit may be essential for channel activity. The N-terminus is important in the assembly of other multimeric ion channels, including the acetylcholine receptor and voltage-gated K+ channels (Li et al. 1992; Verrall & Hall, 1992; Shen et al. 1993; Shen & Pfaffinger, 1995). In a preliminary report, Ahn & Kleyman (1998) demonstrated that overexpression of the N-terminus of α-rENaC inhibited INa. Overexpression of the cytoplasmic N-termini of degenerins, which are closely related to rENaC, also inhibits degenerin channel activity. Thus, the N-terminus of the Deg/ENaC superfamily of ion channels plays an important role in channel function (Fyfe et al. 1998; Horisberger, 1998).

The current view on ENaC channel assembly and function is that all three subunits are required for maximal channel activity, and that the three subunits assemble in the endoplasmic reticulum, are post-translationally modified in the Golgi network, and move to the plasma membrane together (Cheng et al. 1998; Fyfe et al. 1998; Horisberger, 1998). However, one study suggests that individual subunits move independently to the membrane and that co-expression of all three subunits is not necessary for maximal plasma membrane expression (Prince & Welsh, 1998). Adams et al. (1997) reported that ΔNγ-hENaC interacted with α-hENaC but failed to stimulate INa when co-expressed with α-hENaC. In fact, co-expression of ΔNγ-hENaC with α-hENaC decreased INa slightly, and reduced the expression of α-hENaC (Adams et al. 1997), suggesting that interaction of ΔNγ-hENaC with α-hENaC facilitated its degradation. Adams et al. (1997) also reported that at least two domains of γ-rENaC interact with α-rENaC: a domain located within amino acids 3–53 (i.e. the N-terminus) and another, as of yet unidentified domain. Thus, the ability of γ-rENaC to contribute maximally to rENaC function requires the cytoplasmic N-terminus of γ-rENaC.

The N-terminus of ENaC is also important to channel gating. Grunder et al. (Chang et al. 1996; Grunder et al. 1997) demonstrated that point substitutions at a highly conserved glycine residue with a serine in α-rENaC (G95S), β-rENaC (G37S), or γ-rENaC (G40S) dramatically reduced INa by decreasing the open probability (Po) via alterations in the channel open and closed times. Interestingly, the G37S β-rENaC mutation is responsible for pseudohypoaldosteronism type I, which is an inherited disease in humans that causes severe salt wasting, hyperkalaemia, metabolic acidosis and dehydration. We have likewise demonstrated that the N-terminus of α-rENaC is critical for channel gating. Deletion of amino acids 2–109 in α-rENaC altered the kinetic properties of the channel in lipid bilayers without altering the single channel conductance or Po (Berdiev et al. 1998). When expressed in oocytes Δ2–109 α-, β- and γ-rENaC moved to the plasma membrane, yet INa was significantly reduced compared with WT α-, β- and γ-rENaC (Chalfant et al. 1999b). This observation is consistent with the view that the N-terminus of α-rENaC is not absolutely necessary for subunit assembly and movement to the plasma membrane but it is required for maximal channel function. Moreover, these data suggest that the N-terminus does not contribute to the channel pore, but that it regulates channel gating. The N-terminus of numerous ion channels, including Shaker K+ channels, is involved in channel gating (Hoshi et al. 1990; Zagotta et al. 1990).

The cytoplasmic, N-terminus of α- and β-rENaC play an important role in determining the half-life of the channel and thereby the number of channels in the plasma membrane. Ubiquitination of lysine residues (K), which are highly conserved in the N-terminus of α- and β-ENaC, identifies proteins for endocytosis and rapid degradation (Staub et al. 1997). Staub et al. (1997) have shown that ENaC has a short half-life (∼1 h) and is ubiquitinated at key lysine residues in the N-terminus of the α and β subunit. Although point substitutions of K46 and K50 to arginine failed to alter INa or the amount of α-rENaC in the plasma membrane, similar point substitutions in γ-rENaC (Staub et al. 1997) decreased channel ubiquitination and degradation and increased the number of channels in the membrane and INa. However, when the point substitutions in α-rENaC were made in combination with substitutions in γ-rENaC, the effect was synergistic, suggesting that lysine residues in the N-terminus of α- and β-ENaC regulate the number of channels in the membrane and thereby determine INa. In a recent preliminary study we demonstrated that KGDK (amino acids 47–50) in α-rENaC may be an endocytic motif that regulates the number of channels in the plasma membrane (Chalfant et al. 1998, 1999a; M. L. Chalfant, unpublished observations). We observed that deletion of amino acids 47–50 (i.e. KGDK) in α-rENaC increased INa∼4-fold by increasing the number of channels in the plasma membrane. The deletion had no effect on the single channel conductance or on Po. Moreover, the increase in the number of channels in the membrane was due to a decrease in the endocytic retrieval of channels from the plasma membrane. Interestingly, the human α-ENaC subunit is expressed as four transcripts due to alternative splicing in the 5′ region (Voilley et al. 1994; Thomas et al. 1998). One isoform, α-ENaC2, extends the length of the N-terminus by 59 amino acids, which includes a second copy of the KGDK motif. Thus, α-hENaC2 may have a different half-life to that of α-hENaC. In support of the view that KGDK is an endocytic motif, truncation of a similar motif (i.e. RGER) in the mammalian endopeptidase furin also impairs its endocytosis (Voorhees et al. 1995), consistent with the view that this motif may be an endocytic motif (Zagotta et al. 1990). Thus, evidence is accumulating to suggest that the cytoplasmic, N-terminus of ENaC participates in many key functions including endocytic retrieval and degradation, subunit assembly, and gating.

The extracellular loop (domain II)

One distinguishing characteristic of the Deg/ENaC superfamily is that nearly 70 % of the constituent amino acids of each protein lies in the extracellular compartment. As the bulk of the amino acid residues of each ENaC subunit lies in the extracellular solution, much speculation has ensued as to the function of this domain. Yet, very little is known in this regard. There are a number of potential N-linked glycosylation sites on each subunit. For example, in rENaC, there are 6, 12 and 5 glycosylation sites in the α, β and γ subunits, respectively (Canessa et al. 1994b; Renard et al. 1994; Snyder et al. 1994). All these sites are located in this large loop domain between the first and second transmembrane regions (M1 and M2), consistent with this domain being extracellular. The functional significance of these glycosylation sites is unknown. In two sets of experiments, when unglycosylated α-ENaC was co-expressed with wild-type β- and γ-ENaC in Xenopus oocytes, no differences in the absolute magnitude of amiloride-sensitive Na+ current, in amiloride sensitivity, or in relative probability PLi/PNa was seen, as compared with wild-type α-, β- and γ-ENaC-injected oocytes (Canessa et al. 1994b; Snyder et al. 1994). These results would indicate that glycosylation (or lack thereof) of the α subunit is not essential for efficient channel assembly and translocation to the plasma membrane, or for its macroscopic conduction properties. However, the role of glycosylation of the β and/or γ subunits has not yet been thoroughly investigated. Studies on voltage-gated Na+ channels found in excitable cells, which are heavily glycosylated, for example, suggest an important role for glycosylation (James & Agnew, 1987). Voltage-gated Na+ channels in mammalian brain possess α-2,8-sialic acid, a form that occurs otherwise only in cell adhesion molecules, suggesting a role in cell adhesion. Glycosylation may also participate in determining the biophysical properties of these channels. For example, desialylation of batrachotoxin-treated Na+ channels in planar lipid bilayers results in the appearance of subconductance states and some modulation in modal channel gating (Recio-Pinto et al. 1990; Bennett et al. 1997). In contrast, neuraminidase treatment of α-, β- and γ-rENaC in bilayers does not alter the biophysical or pharmacological properties of ENaC (I. I. Ismailov, personal communication). While these results are consistent with those of Canessa et al. (1994b) and Snyder et al. (1994), all these studies nonetheless must be interpreted with caution. Without independent verification, artifactual changes in tertiary or quatenary protein structure could result as a consequence of enzyme treatment. Also, complete deglycosylation or desialylation is difficult to achieve. The role of these polysialyl chains may be to confine the channel to distinct regions on the surface of the membrane and/or to cluster channels or channel subunits together. Amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels are thought to cluster (Smith et al. 1995, 1997; Eaton et al. 1995) and to have very low lateral diffusion coefficients (Smith et al. 1995).

Several studies have demonstrated that extracellular serine proteases, such as tryspin and chymotrypsin and an endogenous protease termed CAP-1, can modulate the activity of ENaC (Vallet et al. 1997, 1998; Chraibi et al. 1998). While the stimulatory effect of low concentrations of these proteases was large (about 20-fold), they have little, if any, effect on any of the biophysical properties of single ENaC channels. Moreover, no apparent change in Na+ channel surface density was found. These observations, coupled with the fact that amiloride could not prevent the stimulatory effect of trypsin (in contrast to the protective influence of amiloride on the inhibitory action of higher concentrations of extracellular trypsin on Na+ channels), suggested that the action of these proteases was not on the channel protein itself, but rather on an as yet unidentified associated protein (Chraibi et al. 1998). In contrast to ENaC, voltage-gated Na+ channels are insensitive to extracellular trypsin (Cooper et al. 1987; Shenkel et al. 1989).

Another distinguishing feature of the extracellular loop of ENaC is that it contains two highly conserved cysteine-rich domains (CRD1 and CRD2) spanning nearly 50 % of the extracellular loop (see Fig. 1). There are a total of 16 cysteines in each of these regions, all the cysteines being conserved among every α-, β- and γ-ENaC subunit thus far identified. Most of these cysteines are also conserved among other branch members of this gene superfamily as well. There are two cysteine-rich domains in the extracellular loop of the BNaCs, PPK and RPK, and FaNaCh, and two or three for the degenerins (see Take-uchi et al. 1998). Firsov et al. (1999) recently investigated by mutational analysis (cysteine to serine or alanine) the functional role that these CRDs may play. A single point mutation within CRD1 of α-rENaC (C158) at a cysteine homologous to human C133 (known to result in a loss-of-function phenotype), and two in CRD2 (C458S, C472S) decreased surface expression of channel moieties, but did not affect biochemical assembly or degradation (Firsov et al. 1999). None of the α-rENaC cysteine mutant constructs displayed any change in amiloride sensitivity, unitary conductance, or cation selectivity. They also found no effect of cysteine-modifying reagents on the mutant channels as compared with that seen for the wild-type channel. These results were interpreted to indicate that, in the heterologously expressing oocyte system, the positions of the cysteines in the extracellular loop were far away from both the channel pore and the amiloride-binding site. The authors hypothesize that the cysteine-rich domains in the extracellular loop are primarily involved in channel movement to the cell surface, and not in protein-protein interactions. These observations are in contrast to other ion channels containing extracellular cysteine-rich regions, like acetylcholine receptors and other ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors, where these cysteine-laden regions play an essential role in channel assembly and oligomerization (Green & Wanamaker, 1997; Green, 1999).

The fact that so much of the primary structure of each ENaC subunit lies in the extracellular region and the fact that amiloride inhibits this channel only from that surface would indicate that the binding site for amiloride would be located somewhere in the extracellular loop domain (Benos, 1982). Moreover, because the α subunit of ENaC can form bona fide amiloride-sensitive channels in a homomeric complex of four (Berdiev et al. 1998), it is likely that an amiloride-binding domain would exist in the α subunit itself. Through the manufacture of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against amiloride itself, one such monoclonal anti-amiloride antibody was used as a surrogate amiloride receptor to identify the amino acid residue types that may form an amiloride-binding site. Analysis of the structure of this anti-amiloride antibody led to the identification of a six amino acid residue track (WYRFHY) within the extracellular loop of α-rENaC in CRD1 (Kieber-Emmons et al. 1995; see Fig. 2). Evidence has also been provided that this six amino acid residue track, α-278–283, is required to confer nanomolar amiloride sensitivity to α-rENaC expressed both in oocytes and reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers (Ismailov et al. 1997). In support of this idea, point mutations within this six amino acid track significantly altered amiloride sensitivity. Deletion of these residues did not affect single-channel conductance, nor did it influence PNa/PK ratios. Li and coworkers (1995) have identified splice variants of α-rENaC in which the C-terminal 199 or 216 amino acid residues were truncated, including the second membrane-spanning domain. These splice variants were not functional when expressed in Xenopus oocytes, but did retain amiloride- and phenamil-binding activity, suggesting that at least part of the amiloride- and phenamil-binding site is proximal to the C-terminal 216 residues of α-rENaC. These observations are in accord with the location of the six amino acid amiloride binding track identified through an anti-idiotypic antibody approach. The sensitivity of α-rENaC to amiloride does not appear to be dependent upon co-expression with β- and γ-rENaC, as wild-type α-rENaC and wild-type αβγ-rENaC heterologously expressed in oocytes or reconstituted into lipid bilayers have similar inhibitory values for amiloride. These observations support the hypothesis that residues essential for the formation of the high affinity amiloride-binding sites reside within the α subunit. Nonetheless, β- and γ-ENaC also participate in amiloride binding (Schild et al. 1997). A track WYKLHY (residues 230–235) within the extracellular loop of γ-rENaC is very similar to the aforementioned amiloride-binding domain in α-ENaC. However, no studies have yet been performed on this region with respect to amiloride binding. This six amino acid amiloride-binding domain is conserved within all the α-ENaCs that have been cloned and sequenced to date. A nearly identical amiloride-binding track (WYHFHY) is present in the recently cloned δ-hENaC as well (Waldmann et al. 1995).

The analysis by Lin et al. (1994) of the amiloride-binding site on the anti-amiloride antibody suggested that a histidine residue within the CDR3 region of the heavy chain IgG primarily interacts with the chloride atom on the pyrazine ring moiety of amiloride through an electrostatic interaction. Mutations of the histidine residue (H282) present within the six amino acid amiloride-binding domain in the extracellular loop of α-rENaC were examined. Mutagenesis of this histidine to aspartic acid (H282D) resulted in a change of charge at this position, with a nearly 40-fold increase in the apparent Ki for amiloride. Mutagenesis of this histidine to arginine (H282R; charge conservation) was associated with a 6-fold decrease in the Ki for amiloride. Nonetheless, Kosari et al. (1998) report that when αH282Dβγ-rENaC was expressed in oocytes, the inhibitory effect of amiloride was indistinguishable from the wild-type channel. The same results were observed when αH282D-rENaC was compared with αH282Dβγ-rENaC in planar lipid bilayers (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the β and γ subunits participate in amiloride binding and may stabilize the binding of amiloride to the hetero-oligomeric channel. Data provided by Adams et al. (1999) support the original suggestion (Benos et al. 1979; Benos & Watthey, 1981) that the Deg/ENaC superfamily of channels may have more than one amiloride interaction site.

Figure 4. Effect of amiloride on αH282D-rENaC and αH282Dβγ-rENaC in planar lipid bilayers.

Experiments were performed in symmetrical 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Mops (pH 7.4). Further experimental details can be found in Ismailov et al. (1997). Each point represents the mean of at least three separate experiments.

Hydrophobic segments (domain III)

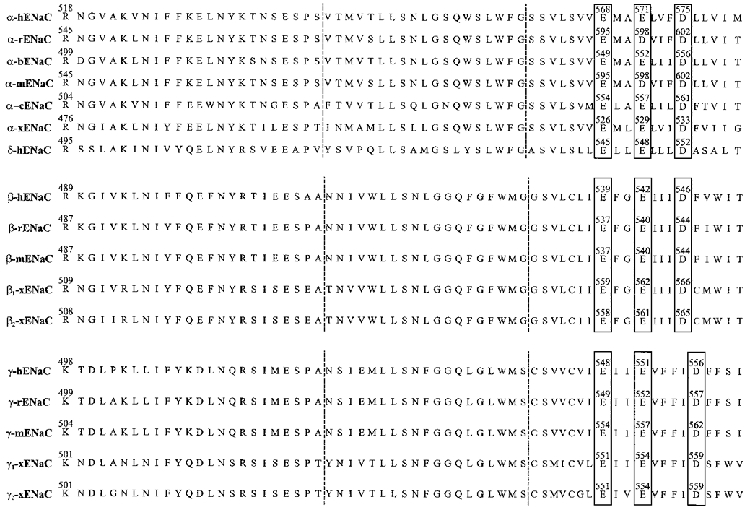

Topological analyses predicted Deg/ENaC proteins contain two hydrophobic segments. Starting from the N-terminus, the first membrane-spanning segment (M1) is immediately followed by a short hydrophobic post-membrane-spanning region (H1). The second hydrophobic region (H2M2) occurs after the large extracellular loop. A suggestion has been made that the hydrophobic domain immediately preceding the second membrane-spanning region of ENaC (the H2 domain) may insert into the membrane as well (Canessa et al. 1994b). Both H1M1 and H2M2 contain around 50 amino acids. The H1M1 segment is much less conserved among family members than is the H2M2 region. Only a few mutations within these regions, especially those within the transmembrane α-helical domains, have been documented and characterized. Waldman et al. (1995) first reported that when the H1M1 region of α-rENaC was replaced by the analogous region from one of the degenerins (Mec 4), the single sodium channel conductance (gNa) of the chimera increased from 4.6 to 5.6 pS, the mean channel open time decreased by a factor of 300, and the affinity to amiloride decreased 3-fold. Replacing H2M2 of α-rENaC with a comparable region from Mec 4 increased gNa to 12.7 pS, decreased the mean open time by nearly three orders of magnitude, and decreased amiloride affinity by a factor of 14. Moreover, this H2M2 domain swap reversed the selectivity of the channel from PLi > PNa to PNa > PLi. Replacing the first part of M2, namely, amino acids 589–594 (SVLSVV) of α-rENaC with a comparable region from Mec 4, produced a chimeric channel with properties similar to the chimera with the entire H2M2 domain swapped. Swapping the latter half of M2, namely, amino acids 596–601 (MADVIF), resulted in a chimera with properties virtually indistinguishable from the wild-type channel. Moreover, a single-point mutation (S589I) resulted in a channel having characteristics altered from those of the wild-type channel, but identical to the H2M2 chimera. The point mutant S593I increased gNa, induced a fast voltage-dependent gating, and produced a 50-fold decrease in amiloride affinity. These observations suggested that both S589 and S593 are located within the ion conduction pathway itself. Thus, the H2M2 region appears more critical in terms of ion conductance and selectivity than the H1M1 region, and both hydrophobic domains are important in terms of channel gating. These results will be discussed further below. Schild et al. (1997) reached similar conclusions concerning the selectivity and conduction properties conferred by the H2M2 region. Mutagenesis of residues within the H2 region of rat α-, β- or γ-ENaC (αW582L, βG525C or γG537C) altered ENaC single channel conductance, providing evidence that these residues within this H2 region may also contribute to the cation pore. Specifically, the αS583C mutation did not affect channel conductance, while a cysteine mutation at the corresponding positions in the β and γ subunits (βG525C and γG537C) resulted in an approximately 40-fold decrease in gNa. These mutations, however, did not have any effect on PNa/PLi permeability ratios. Thus, these observations suggest that the glycine to cysteine mutations in the β and γ subunits affect ion conduction without effects on cation selectivity or channel gating. There was little effect on single channel sodium or lithium conduction either in the presence or in the absence of calcium in either the α or β subunits for αS580D or βG522D substitutions. However, these mutations did increase the sensitivity of the channel to external calcium block. Interestingly, the αS580D and γG534E mutations did not alter amiloride block, but mutations at the corresponding position in the β subunit decreased amiloride sensitivity by one to two orders of magnitude. A recent paper by Kellenberger et al. (1999a, b) focused on the serine at position 589 in α-rENaC in the second transmembrane domain. These authors concluded that this serine residue is critical for the high sodium and lithium selectivity of this channel over potassium ions. A series of different amino acid substitutions at this position allowed permeation of normally impermeant cations such as potassium, rubidium and caesium, as well as divalents. These authors concluded that this serine residue in M2 acts as part of the selectivity filter as a molecular sieve. However, it is reasonable to assume that this residue also forms part of the channel pore as well.

Our laboratory (Fuller et al. 1997) generated two site-directed mutants (K504E and K515E) in the α subunit of the bovine epithelial channel (α-bENaC). These mutations would correspond to K550 and K561 of α-rENaC (see Fig. 5). The region in which these mutations lie are in the pre-H2 region of the protein (in the extracellular loop) and are conserved in all the cloned ENaC subunits. Using planar lipid bilayers as our assay system, we found that these mutants decreased or eliminated the long, closed states characteristic of α-bENaC, significantly reduced the sodium to potassium permeability from over 10:1 for sodium:potassium to 2–3:1 for each of the mutations, and decreased the apparent affinity for amiloride inhibition by one order of magnitude. Importantly, there was no change in single channel conductance. Thus, we hypothesize that M2 and the second (or distal) half of the H2 domain constitute the walls of the conduction pathway of the channel and the pore helix region, i.e. pre-H2 and the proximal half of H2 form part of the cation selectivity filter. Moreover, this entire pre-M2 region appears to be involved in amiloride binding. While these results may apply to homomeric channels consisting only of α subunits (see Kellenberger et al. 1999b), any comprehensive view of Na+ channel selectivity, conductance and permeability must take these results into account (see also Kieber-Emmons et al. 1999).

Figure 5. Amino acid alignment of α(δ)-, β- and γ-ENaC in the region of the second large hydrophobic domain (H2M2).

The domain between the vertical dotted lines is H2, and the region to the right of the second vertical dotted line is the M2 region (partial).

To examine the hypothesis that M2-containing residues comprise the walls of the aqueous conduction pathway, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on certain critical amino acids within this domain. There are a total of four negatively charged residues within the two transmembrane domains of α-ENaC, one (E108 in α-hENaC) in M1 and three in M2 (E568, E571, and E575 in α-hENaC). α-Helical wheel analysis of the M2 hydrophobic domain of α-ENaC indicates that the three negatively charged residues are positioned on the hydrophilic face of the helix. These residues are conserved among all the known orthologues of the ENaCs (Fig. 5). Thus, it is likely that these negative charges line the channel conduction pathway and would therefore be critical to channel function. To test this idea Langloh et al. (1999) reversed these charges individually and in various combinations, and examined the effects of these mutations on whole-cell and single channel Na+ currents subsequent to expression in Xenopus oocytes (in combination with wild-type β and γ subunits). All three individual mutants displayed a significantly reduced single channel conductance, but with no change in PNa/PK or amiloride sensitivity. No functional alterations were observed in channels composed of wild-type β- and γ-hENaC, and an α-hENaC containing a mutation of the single negatively charged residue in M1, namely, E108R. These observations are in concordance with the idea the M2 residues distal to S589 (in α-rENaC; S565 in α-hENaC; see Fig. 5) line the channel pore, and that M1 itself is not part of the conduction pathway. However, Coscoy et al. (1999) suggest that the region just preceding M1 (in the N-terminus of ASIC) also contributes to the channel pore.

Thus, the current paradigm for understanding the selectivity/conduction features of Mec/ENaC can be summarized as follows. The pre-H2M2, the H2 and the most proximal part of the M2 regions of each subunit (along with part of the pre-M1 domain) may form the cation selectivity filter of the channel in addition to containing residues that are essential for inhibition of the channel by both amiloride and divalent cations. The distal H2 domain may also contribute, along with the M2 region, residues that constitute the ion conduction pathway through the lipid bilayer membrane. The actual selectivity filter of these channels must be proximal to amino acid residue E568 in α-hENaC (E595 of α-rENaC) because mutagenesis of this residue does not affect ion selectivity.

Carboxy terminal tails (domain IV)

The hydrophobic carboxy-terminal tail of each member of the Deg/ENaC superfamily, like the N-terminus, lies in the cytoplasm and thus plays a potentially important function in ion channel regulation. Moreover, because this domain is the least conserved among family members, observed species or tissue differences in amiloride-sensitive sodium channel regulatory responses to similar agonists or antagonists may result. For example, in airway and renal epithelia, β-adrenergic agonists or cAMP stimulate amiloride-sensitive sodium transport (Matalon et al. 1996). This does not occur in colon, in spite of the fact that the three ENaC subunits are present in all these locales. Different proportions of subunits and hence different possible channel compositions (McNicholas & Canessa, 1997) may also contribute to this variation in response. Alternatively, the presence or absence of intermediate effector or accessory proteins in different tissues may ultimately determine the response.

Although ENaC does not contain any consensus protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation sites, Shimkets et al. (1998) reported that the β- and γ-carboxy tails can be phosphorylated by PKA as well as by protein kinase C, aldosterone and insulin. However, at least for PKA, this phosphorylation does not translate into a direct modulation of ENaC activity in oocytes or in bilayers (Awayda et al. 1996). More likely, this phosphorylation may prime the channel to accommodate or promote the tissue-specific interaction of ENaC regulatory cellular proteins that mediate the appropriate response. In contrast, PKC decreases single αβγ-ENaC open probability (Po) directly in cells, oocytes, or in bilayers (Kokko et al. 1994; Awayda et al. 1996; Frindt et al. 1996).

The importance of the β- and γ-carboxy tails of ENaC is underlined by studies linking missense, frameshift, or stop mutations within these regions to a human genetic hypertensive disease, Liddle's Syndrome (Hansson et al. 1995a, b; Warnock, 1998; Kellenberger et al. 1998). In this disease, either mutations truncating the last 45–75 amino acids of the β or γ subunits, or point mutations within a proline-rich region in these same C-termini result in a gain of channel function such that sodium is re-absorbed with great avidity. The identification of specific interaction sites within these C-terminal regions for the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 (Staub et al. 1996, 1997) and spectrin suggest that interactions with cytosolic components and the cytoskeleton may control the expression and activity of ENaC at the plasma membrane. Indeed, Goulet et al. (1998) and Abriel et al. (1999) report that co-expression of Nedd4 with ENaC in oocytes inhibited ENaC activity, specifically by decreasing the surface density of ENaC. The negative regulatory effects of Nedd4 were critically dependent upon these proline-rich motifs because no Nedd4-mediated alterations in channel activity were seen in ENaCs not possessing them. This proline-rich motif, PPPXYXXL, is conserved in the carboxy tail of all three ENaC subunits, and functions as a tyrosine-based internalization sequence (Staub et al. 1996). In addition, this same sequence is compatible with a PY-motif (PPXY) shown to be involved in protein-protein interactions (Chen & Sudol, 1995), specifically with proteins containing at least two conserved tryptophan residues (WW domains). Nedd4 contains three WW domains (Staub et al. 1997). Binding of Nedd4 to the PY domain of ENaC permits ubiquitination of the channel (at key lysine residues in the N-terminus), with concomitant endocytosis and degradation. Hence, in ENaCs lacking PY domains (as is the case in Liddle's syndrome), channel internalization rates would be depressed with the resulting effect of an increased channel number at the membrane surface (Schild et al. 1996; Hugues et al. 1999). Moreover, the proline-rich region could bind to SH3 domains in certain PDZ-containing proteins and thereby localize ENaC, in macromolecular complexes containing numerous signalling molecules and other ion channels, to the apical membrane of Na+ resorbing epithelia. Rotin et al. (1994) observed that the C-terminal proline-rich regions were important for sorting to the apical membrane, and that disruption of these regions blocked apical channel expression.

However, there also is strong evidence suggesting that, at least for the truncation Liddle's mutants, single channel open probability is increased (Awayda et al. 1996; Firsov et al. 1996; Ismailov et al. 1996, 1999), although some laboratories have not reported increases in ENaC Po with β or γ subunit truncation mutations (Snyder et al. 1995; Fyfe & Canessa, 1998). The observation of an increased single channel Po in channels lacking a β- or γ-ENaC C-terminal tail led to the hypothesis that the C-terminal regions of the β and γ subunits could function as inhibiting peptides of rENaC.

We found that for channels in which the β- and/or γ-ENaC carboxy tails were removed, 10 or 30 amino acid peptides constructed from the C-terminal tails of either of these subunits can effectively reduce single channel open probability by locking the channel in its closed state. In addition, there appears to be a synergy between the actions of the β and γ peptides. When present in solution together, the inhibition was greater than that produced by the individual peptides themselves. Thus, the protocol that we have developed for ENaC channel gating is as follows. As α-ENaC itself can form a functional sodium channel, there must be an intrinsic gating mechanism in α-ENaC alone. This gating mechanism has not yet been elucidated, but, as indicated earlier, may involve the cytoplasmic N-termini and intracellular calcium. As elimination of the cytoplasmic C-terminal tails of either or both of the β and γ subunits substantially increases single channel Po, there must be at least two separate gating processes, one inherent to α-rENaC alone and one conferred onto the complex by the β and γ subunits. Moreover, based on intrinsic fluorescence measurements and circular dichroism spectroscopy, evidence has been provided showing that these C-terminal peptides adopt a β-sheet conformation in solution and interact (Ismailov et al. 1999). Only the β- and γ-ENaC C-termini are predicted to form β-sheets. Thus, we hypothesize that the C-terminal cytoplasmic carboxy tails of the β- and γ-ENaC subunits act in concert as a ‘single’ inactivation peptide by binding to an internal region of an active sodium channel and then closing the channel. However, the inhibition of the channel by these peptides is distinctly different from the ‘ball and chain’ model proposed for blockade of Shaker potassium channels in that the peptides are not acting as open channel blockers. Thus, for β- and/or γ-ENaC truncation mutants found in Liddle's disease, there would be two consequences: (1) a decreased internalization of the channel and (2) an increase in open channel probability. This situation would be predicted not to exist for the single point mutations found in the proline-rich region. Under these circumstances, it is more likely that the decrease in internalization would be the predominant mode of increased macroscopic current. These predictions await experimental tests.

Summary and prospectus

Amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels are a diverse group of ion channels. They display complex gating kinetics, intricate regulatory patterns, and biophysical and pharmacological properties that are dependent upon their biochemical state and physical surroundings. Most importantly, these channels interact with numerous accessory proteins, including serine proteases, cytoskeletal elements like actin and spectrin, and even other ion channels, for example, CFTR. These channels are widely distributed, and it is thus not surprising that the malfunctions in the operation or regulation of these channels result in deleterious consequences for the cell, tissue or organism in which they are found. Several human diseases have been directly linked to specific genetic alterations in ENaC. Yet, the elucidation of the functional relationships of these interesting and important ion channels is still in its infancy.

Despite intensive investigation, mechanisms underlying the regulation of the Deg/ENaC family of ion channels are still unclear because it has proved difficult to translate observations made by macroscopic tissue measurements of Na+ transport to the molecular level. This is particularly true when it comes to assessment of the effects of intracellular second messengers on these channels. It is our contention that understanding the structure–function relationships of Deg/ENaC can only assist in this regard. It is only recently that the crystal structure of a two-pass K+ channel was determined (Doyle et al. 1998). It is reassuring to observe how accurately molecular cloning and mutagenesis experiments predicted the actual structure of the K+ channel pore (Armstrong, 1998; Clapham, 1998). In the absence of a crystal structure for Deg/ENaC, mutagenesis is the chosen route for exploration. A caveat of any mutagenesis-type experiments is that while a mutation may affect channel properties to some extent, for example, the many mutations noted to affect amiloride sensitivity, it does not necessarily imply that that residue plays a direct role in the particular property being investigated. Alterations in the primary sequence of a protein can have effects on the structure beyond those anticipated. Given that the channel subunits are likely to be highly folded and perhaps even intertwined, these local structural distortions produced by a given amino acid mutation may propagate to distant regions of the subunit or even to other associated or interacting proteins. Without knowledge of the structure of the channel, its stoichiometry, or, more importantly, in the absence of knowledge of the effects of the mutations on protein structure, there is no definite solution to this problem. Still, useful structure–function information has emerged for Deg/ENaC with this approach, generating exciting new hypotheses concerning Deg/ENaC regulation and biophysical properties. We argue that this approach has been, and will be, essential, not only for understanding the molecular correlates underlying Na+ channel physiology, but also for extrapolation to disease states involving this channel. Moreover, molecular targeting of regulatory sites will undoubtedly permit the development of new strategies to circumvent the unwanted activation of these channels in certain types of disease, and thus have important therapeutic ramifications (see Bubien et al. 1999). In the final analysis, the success of this mutagenesis approach will be measured against the actual, eagerly awaited, but yet-to-be determined, crystal structure of the channel.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cathleen Guy and Shea Thompson for excellent secretarial assistance and Katherine Karlson for assistance with Fig. 3. We also thank Dr Catherine Fuller for her comments on the manuscript. The preparation of this review was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-37206, DK-56095, DK-34533 and DK-51067.

References

- Abriel H, Loffing J, Rebhun JF, Pratt JH, Schild L, Horisberger JD, Rotin D, Staub O. Defective regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by Nedd4 in Liddle's syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:667–673. doi: 10.1172/JCI5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CM, Anderson MG, Motto DG, Price MP, Johnson WA, Welsh MJ. Ripped pocket and pickpocket, novel Drosophila DEG/ENaC subunits expressed in early development and in mechanosensory neurons. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;140:143–152. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CM, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. Interactions between subunits of the human epithelial sodium channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:27295–27300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CM, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. Paradoxical stimulation of a DEG/ENaC channel by amiloride. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:15500–15504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn YJ, Kleyman TR. Cytoplasmic N-terminal domain of α-mENaC abolishes Na channel expression in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1998;9:29A. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C. The vision of the pore. Science. 1998;280:56–57. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awayda MS, Ismailov II, Berdiev BK, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Protein kinase regulation of a cloned epithelial Na+ channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:49–65. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babinski K, Le K-T, Seguela P. Molecular cloning and regional distribution of a human proton receptor subunit with biphasic functional properties. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72:51–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbry P, Hofman P. Molecular biology of Na+ absorption. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:G571–585. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.3.G571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassilana R, Champigny G, Waldmann R, De Weille JR, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. The acid-sensitive ionic channel subunit ASIC and the mammalian degenerin MDEG form a heteromultimeric H+-gated Na+ channel with novel properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:28819–28822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E, Urcan MS, Tinkle SS, Koszowski AG, Levinson SR. Contribution of sialic acid to the voltage dependence of sodium channel gating. A possible electrostatic mechanism. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:327–343. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ. Amiloride: A molecular probe of sodium transport in tissues and cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1982;242:C131–145. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.242.3.C131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ. The biology of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels. Hospital Practice. 1989;24:149–164. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1989.11703701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ, Awayda MS, Berdiev BK, Bradford AL, Fuller CM, Senyk O, Ismailov II. Diversity and regulation of amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels. Kidney International. 1996;49:1632–1637. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ, Awayda MS, Ismailov II, Johnson JP. Structure and function of amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;143:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00232519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ, Mandel LJ, Balaban RS. On the mechanism of the amiloride-sodium entry site interaction in Anuran skin epithelia. Journal of General Physiology. 1979;73:307–326. doi: 10.1085/jgp.73.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benos DJ, Watthey JWH. Inferences on the nature of the apical sodium entry site in frog skin epithelium. Journal of Pharmacological Experimental Therapy. 1981;219:481–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdiev BK, Karlson KH, Jovov B, Ripoll PJ, Morris R, Loffing-Cueni D, Halpin P, Stanton BA, Kleyman TR, Ismailov II. Subunit stoichiometry of a core conduction element in a cloned epithelial amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. Biophysical Journal. 1998;75:2292–2301. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77673-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubien JK, Keeton DA, Fuller CM, Gillespie GY, Reddy AT, Mapstone TB, Benos DJ. Malignant human gliomas express an amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductance. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:C1405–1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.6.C1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa C, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Epithelial sodium channel related to proteins involved in neurodegeneration. Nature. 1993;361:467–470. doi: 10.1038/361467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa C, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature. 1994a;367:463–467. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM. What is new about the structure of the epithelial Na+ channel? News in Physiological Sciences. 1996;11:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM, Merillat A-M, Rossier BC. Membrane topology of the epithelial sodium channel in intact cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1994b;267:C1682–1690. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant ML, Denton JS, Karlson KH, Stanton BA. The N-terminus of the α-subunit of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) regulates its stability in the plasma membrane. FASEB Journal. 1999a;13:A66. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant ML, Denton JS, Langlogh AL, Karlson KH, Loffing J, Benos DJ, Stanton BA. The N-terminus of the epithelial sodium channel contains an endocytic motif. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999b. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chalfant M, Karlson K, McCoy D, Denton J, Stanton BA. The N-terminus of the a subunit of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) regulates channel function. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1998;9:32A. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Wolinsky E. The identification and suppression of inherited neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1990;345:410–416. doi: 10.1038/345410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SS, Grunder S, Hanukoglu A, Rosler A, Mathew PM, Hanukoglu I, Schild L, Lu Y, Shimkets RA, Nelson-Williams C, Rossier BC, Lifton RP. Mutations in subunits of the epithelial sodium channel cause salt wasting with hyperkalaemic acidosis, pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1. Nature Genetics. 1996;12:248–253. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HI, Sudol M. The WW domain of yes-associated protein binds a proline-rich ligand that differs from the consensus established for Src homology 3-binding modules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:7819–7823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Prince LS, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. Assembly of the epithelial Na+ channel evaluated using sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:22693–22700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chraibi A, Vallet V, Firsov D, Hess SK, Horisberger J-D, Chalfant M, Karlson K, McCoy D, Denton J, Stanton BA. Protease modulation of the activity of the epithelial sodium channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:127–138. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. At last, the structure of an ion-selective channel. Nature Structural Biology. 1998;5:342–344. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EC, Tomiko SA, Agnew WS. Reconstituted voltage-sensitive sodium channel from Electrophorus electricus: Chemical modifications that alter regulation of ion permeability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1987;84:6282–6286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coscoy S, de Weille JR, Lingueglia E, Lazdunski M. The pre-transmembrane 1 domain of acid-sensing ion channels participates in the ion pore. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:10129–10132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darboux I, Lingueglia E, Champigny G, Coscoy S, Barbry P, Lazdunski M. dGNaC1, a gonad-specific amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998a;273:9424–9429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darboux I, Lingueglia E, Pauron D, Barbry P, Lazdunski M. A new member of the amiloride-sensitive sodium channel family in Drosophila melanogaster peripheral nervous system. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1998b;246:210–216. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: Molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–76. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll M, Chalfie M. The Mec-4 gene is a member of a family of Caenorhabditis elegans genes that can mutate to induce neuronal degeneration. Nature. 1991;349:588–593. doi: 10.1038/349588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DC, Becchetti A, Ma H, Ling BN. Renal sodium channels: regulation and single channel properties. Kidney International. 1995;48:941–949. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firsov D, Robert-Nicoud M, Gruender S, Schild L, Rossier BC. Mutational analysis of cysteine-rice domains of the epithelium sodium channel (ENaC) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:2743–2749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firsov D, Schild L, Gautschi I, Merillat AM, Schneeberger E, Rossier BC. Cell surface expression of the epithelial Na channel and a mutant causing Liddle syndrome: a quantitative approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:15370–15375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frindt G, Palmer LG, Windhager EE. Feedback regulation of Na channels in rat CCT. IV meditation by activation of protein kinase C. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:F371–376. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.2.F371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Berdiev BK, Shlyonsky VG, Ismailov II, Benos DJ. Point mutations in α-bENaC regulate channel gating, ion selectivity, and sensitivity to amiloride. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:1622–1632. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78808-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe GK, Canessa CM. Subunit composition determines the single channel kinetics of the epithelial sodium channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;112:423–432. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe GK, Quinn A, Canessa CM. Structure and function of the Mec-ENaC family of ion channels. Seminars in Nephrology. 1998;18:138–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Anoveros J, Derfler B, Neville-Golden J, Hyman BT, Corey DP. BNaC1 and BNaC2 constitute a new family of human neuronal sodium channels related to degenerins and epithelial sodium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1459–1464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Anoveros J, Garcia JA, Liu J-D, Corey DP. The nematode degenerin UNC-105 forms ion channels that are activated by degeneration- or hypercontraction-causing mutations. Neuron. 1998;20:1231–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garty H, Palmer LG. Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure, and regulation. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:359–396. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet CC, Volk KA, Adams CM, Prince LS, Stokes JB, Snyder PM. Inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel by interaction of Nedd4 with a PY motif deleted in Liddle's syndrome. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:30012–30017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.30012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KA, Falconer SWP, Cottrell GA. The neuropeptide Phe-Met-Arg-Phe-NH2 (FMRFamide) directly gates two ion channels in an identified helix neuron. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;428:232–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00724502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN. Ion channel assembly: Creating structures that function. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:163–169. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WN, Wanamaker CP. The role of the cystine loop in acetylcholine receptor assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:20945–20953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunder S, Firsov D, Chang SS, Jaeger NF, Gautschi I, Schild L, Lifton RP, Rossier BC. A mutation causing pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 identifies a conserved glycine that is involved in the gating of the epithelial sodium channel. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:899–907. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson JH, Nelson-Williams C, Suzuki H, Schild L, Shimkets RA, Lu Y, Cnessa CM, Iwasaki T, Rossier BC, Lifton RP. Hypertension caused by a truncated epithelial sodium channel γ-subunit: genetic heterogeneity of Liddle syndrome. Nature Genetics. 1995a;11:76–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson JH, Schild L, Lu Y, Wilson TA, Gautschi I, Shimkets R, Nelson-Williams C, Rossier BC, Lifton RP. A de novo missense mutation of the β-subunit of the epithelial sodium channel causes hypertension and Liddle syndrome, identifying a proline-rich segment critical for regulation of channel activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995b;92:11495–11499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horisberger JD. Amiloride-sensitive Na channels. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1998;10:443–449. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 1990;250:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.2122519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugues A, Loffing J, Rebhun JF, Pratt JH, Schild L, Horisberger J-D, Rotin D, Staub O. Defective regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by Nedd4 in Liddle's syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:667–673. doi: 10.1172/JCI5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummler E, Barker P, Gatzy J, Beermann F, Verdumo C, Schmidt A, Boucher R, Rossier BC. Early death due to defective neonatal ‘lung’ liquid clearance in alpha-ENaC-deficient mice. Nature Genetics. 1996;12:325–328. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Marunaka Y, Rotin D. Electrophysiological characterization of the rat epithelial Na+ channel (rENaC) expressed in MDCK cells. Effects of Na+ and Ca2+ Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:825–846. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismailov II, Awayda MS, Berdiev BK, Bubien JK, Lucas JE, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Triple-barrel organization of ENaC, a cloned epithelial Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:807–816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismailov II, Kieber-Emmons T, Lin C, Berdiev BK, Shlyonsky VGh, Patton HK, Fuller CM, Worrell R, Zuckerman JB, Sun W, Eaton DC, Benos DJ, Kleyman TR. Identification of an amiloride binding domain within the a-subunit of the epithelial Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:21075–21083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismailov II, Shlyonsky VGh, Serpersu EH, Fuller CM, Cheung HC, Muccio D, Berdiev BK, Benos DJ. Peptide inhibition of ENaC. Biochemistry. 1999;38:354–363. doi: 10.1021/bi981979s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain L, Chen X-J, Malik B, Al-Khalili O, Eaton D. Antisense oligonucleotides against the α-subunit of ENaC decrease lung epithelial cation-channel activity. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:L1046–1051. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.6.L1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James WM, Agnew WS. Multiple oligosaccharide chains in the voltage-sensitive Na channel from Electrophorus electricus: Evidence for α-2,8-linked polysialic acid. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1987;148:817–826. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90949-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger S, Gautschi I, Rossier BC, Schild L. Mutations causing Liddle syndrome reduce sodium-dependent downregulation of the epithelial sodium channel in the Xenopus oocyte expression system. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:2741–2750. doi: 10.1172/JCI2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger S, Gautschi I, Schild L. A single point mutation in the pore region of the epithelial Na+ channel changes ion selectivity by modifying molecular sieving. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999a;96:4170–4175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger S, Hoffmann-Pochon N, Gautschi I, Schneeberger E, Schild L. On the molecular basis of ion permeation in the epithelial Na+ channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1999b;114:13–30. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieber-Emmons T, Lin C, Foster MH, Kleyman TR. Antiidiotypic antibody recognizes an amiloride binding domain within the a subunit of the epithelial Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:9648–9655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieber-Emmons T, Lin C, Prammer KV, Villalobos A, Kosari F, Kleyman TR. Defining topological similarities among ion transport proteins with anti-amiloride antibodies. Kidney International. 1995;48:956–964. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokko JE, Matsumoto PS, Ling BN, Eaton DC. Effects of prostaglandin E2 on amiloride-blockable Na+channels in a distal nephron cell line. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C1414–1425. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosari F, Sheng S, Li J, Mak D-O D, Foskett JK, Kleyman TR. Subunit stoichiometry of the epithelial sodium channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:13469–13474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langloh ALB, Berdiev B, Ji H-L, Keyser K, Stanton BA, Benos DJ. Charged residues in the M2 region of α-hENaC play a role in channel conductance. American Journal of Physiology. 1999. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Specification of subunit assembly by the hydrophilic amino-terminal domain of the Shaker potassium channel. Science. 1992;257:1225–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1519059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XJ, Xu RH, Guggino WB, Snyder SH. Alternatively spliced forms of the alpha subunit of the epithelial sodium channel: distinct sites for amiloride binding and channel pore. Molecular Pharmacology. 1995;47:1133–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Kieber-Emmons T, Villalobos AP, Foster MH, Wahlgren C, Kleyman TR. Topology of an amiloride-binding protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:2805–2813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingueglia E, Champigny G, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. Cloning of the amiloride-sensitive FMRFamide peptide-gated sodium channel. Nature. 1995;378:730–733. doi: 10.1038/378730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingueglia E, de Weille JR, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Sakai H, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. A modulatory subunit of acid sensing ion channels in brain and dorsal root ganglion cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:29778–29783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingueglia E, Voilley N, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. Expression cloning of an epithelial amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. A new channel type with homologies to Caenorhabditis elegans degenerins. FEBS Letters. 1993;318:95–99. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald FJ, Yang B, Hrstka RF, Drummond HA, Tarr DE, McCray PB, Jr, Stokes JB, Welsh MJ, Williamson RA. Disruption of the β subunit of the epithelial Na+ channel in mice: Hyperkalemia and neonatal death associated with a pseudohypoaldosteronism phenotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:1727–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas CM, Canessa CM. Diversity of channels generated by different combinations of epithelial sodium channel subunits. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:681–692. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matalon S, Benos DJ, Jackson RM. Biophysical and molecular properties of amiloride-inhibitable Na+ channels in alveolar epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:L1–22. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.1.L1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. Families of ion channels with two hydrophobic segments. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1996;8:474–483. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brodovich H. Epithelial ion transport in the fetal and perinatal lung. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:C555–564. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MP, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. Cloning and expression of a novel human brain Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:7879–7882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince LS, Welsh MJ. Cell surface expression and biosynthesis of epithelial Na+ channels. Biochemistry. 1998;336:705–710. doi: 10.1042/bj3360705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio-Pinto E, Thornhill WB, Duch DS, Levinson SR, Urban BW. Neuraminidase treatment modifies the function of electroplax sodium channels in planar lipid bilayers. Neuron. 1990;5:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90221-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard S, Lingueglia E, Voilley N, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. Biochemical analysis of the membrane topology of the amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:12981–12986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotin D, Bar-Sagi D, O'Brodovich H, Merilainen J, Lehto VP, Canessa CM, Rossier BC, Downey GP. An SH3 binding region in the epithelial Na+ channel (α-rENaC) mediates its location at the apical membrane. EMBO Journal. 1994;13:4440–4450. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild L, Lu Y, Gautschi I, Schneeberger E, Lifton RP, Rossier BC. Identification of a PY motif in the epithelial Na channel subunits as a target sequence for mutations causing channel activation found in Liddle syndrome. The. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:2381–2387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild L, Schneeberger E, Gautschi I, Firsov D. Identification of amino acid residues in the α, β, and γ subunits of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) involved in amiloride block and ion permeation. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:15–26. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Benos DJ, Egan ME, Stutts MJ, Guggino WB. CFTR is a conductance regulator as well as a chloride channel. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:S145–166. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen NV, Chen X, Boyer MM, Pfaffinger PJ. Deletion analysis of K+ channel assembly. Neuron. 1993;11:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90271-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen NV, Pfaffinger PJ. Molecular recognition and assembly sequences involved in the subfamily-specific assembly of voltage-gated K+ channel subunit proteins. Neuron. 1995;14:625–633. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenkel S, Cooper EC, James W, Agnew WS, Sigworth FJ. Purified, modified eel sodium channels are active in planar bilayers in the absence of activating neurotoxins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:9592–9596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimkets RA, Lifton R, Canessa CM. In vivo phosphorylation of the epithelial sodium channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:3301–3305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PR, Bradford AL, Schneider S, Benos DJ, Geibel JP. Localization of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels in A6 cells by atomic force microscopy. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C1295–1298. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PR, Stoner LC, Viggiano SC, Angelides KJ, Benos DJ. Effects of vasopressin and aldosterone on the lateral mobility of epithelial Na+ channels in A6 renal epithelial cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;147:195–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00233547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PM, McDonald FJ, Stokes JB, Welsh MJ. Membrane topology of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:24379–24383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PM, Price MP, McDonald FJ, Adams CM, Volk KA, Zeiher BG, Stokes JB, Welsh MJ. Mechanism by which Liddle's syndrome mutations increase activity of a human epithelial Na+ channel. Cell. 1995;83:969–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub O, Dho S, Henry PD, Correa J, Ishikawa T, McGlade J, Rotin D. WW domains of Nedd4 bind to the proline-rich PY motifs in the epithelial Na+ channel deleted in Liddle's syndrome. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:2371–2380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub O, Gautschi I, Ishikawa T, Breitschopf K, Ciechanover A, Schild L, Rotin D. Regulation of stability and function of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) by ubiquitination. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:6325–6336. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Take-uchi M, Kawakami M, Ishihara T, Amano T, Kondo K, Katsura I. An ion channel of the degenerin/epithelial sodium channel superfamily controls the defecation rhythm in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:11775–11780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CP, Auerbach S, Stokes JB, Volk KA. 5′ Heterogeneity in epithelial sodium channel a-subunit mRNA leads to distinct NH2-terminal variant proteins. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C1312–1323. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet V, Chraibi A, Gaeggeler H-P, Horisberger J-D, Rossier BC. An epithelial serine protease activates the amiloride-sensitive sodium channel. Nature. 1997;389:607–610. doi: 10.1038/39329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet V, Horisberger J-D, Rossier BC. Epithelial sodium channel regulatory proteins identified by functional expression cloning. Kidney International. 1998;54(suppl. 67):S109–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrall S, Hall ZW. The N-terminal domains of acetylcholine receptor subunits contain recognition signals for the initial steps of receptor assembly. Cell. 1992;68:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90203-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voilley N, Galibert A, Bassilana F, Renard S, Lingueglia E, Coscoy S, Champigny G, Hofman P, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. The amiloride-senstive Na+ channel: from primary structure to function. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1997;118A:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(97)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voilley N, Lingueglia E, Champigny G, Mattéi M-G, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. The lung amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel: Biophysical properties, pharmacology, ontogenesis, and molecular cloning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:247–251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees P, Deignan E, van Donselaar E, Humphrey J, Marks MS, Peters PJ, Bonifacino JS. An acidic sequence within the cytoplasmic domain of furin functions as a determinant of trans-Golgi network localization and internalization from the cell surface. EMBO Journal. 1995;14:4961–4975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Bassilana R, de Weille J, Champigny G, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. Molecular cloning of a non-inactivating proton-gated Na+ channel specific for sensory neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997a;272:20975–20978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.20975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature. 1997b;386:173–177. doi: 10.1038/386173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Voilley N, Lazdunski M. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a novel amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:27411–27414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Lazdunski M. Functional degenerin-containing chimeras identify residues essential for amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel function. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:11735–11737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Voilley N, Lauritzen I, Lazdunski M. The mammalian degenerin MDEG, an amiloride-sensitive cation channel activated by mutations causing neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:10433–10436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. H(+)-gated cation channels: Neuronal acid sensors in the NaC/DEG family of ion channels. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1998;8:418–424. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock DG. Liddle syndrome: An autosomal dominant form of human hypertension. Kidney International. 1998;53:18–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]