Abstract

The effects of prolonged conditioning depolarizations on the activation kinetics of skeletal L-type calcium currents (L-currents) were characterized in mouse myotubes using the whole-cell patch clamp technique.

The sum of two exponentials was required to adequately fit L-current activation and enabled determination of both the amplitudes (Afast and Aslow) and time constants (τfast and τslow) of each component comprising the macroscopic current. Prepulses sufficient to activate (200 ms) or inactivate (10 s) L-channels did not alter τfast, τslow, or the fractional contribution of either the fast (Afast/(Afast + Aslow)) or slow (Aslow/(Afast + Aslow)) amplitudes of subsequently activated L-currents.

Prolonged depolarizations (60 s to +40 mV) resulted in the conversion of skeletal L-current to a fast gating mode following brief repriming intervals (3-10 s at -80 mV). Longer repriming intervals (30-60 s at -80 mV) restored L-channels to a predominantly slow gating mode. Accelerated L-currents originated from L-type calcium channels since they were completely blocked by a dihydropyridine antagonist (3 μM nifedipine) and exhibited a voltage dependence of activation similar to that observed in the absence of conditioning prepulses.

The degree of L-current acceleration produced following prolonged depolarization was voltage dependent. For test potentials between +10 and +50 mV, the fractional contribution of Afast to the total current decreased exponentially with the test voltage (e-fold ∼38 mV). Thus, L-current acceleration was most significant at more negative test potentials (e.g. +10 mV).

Prolonged depolarization also accelerated L-currents recorded from myotubes derived from RyR1-knockout (dyspedic) mice. These results indicate that L-channel acceleration occurs even in the absence of RyR1, and is therefore likely to represent an intrinsic property of skeletal L-channels.

The results describe a novel experimental protocol used to demonstrate that slowly activating mammalian skeletal muscle L-channels are capable of undergoing rapid, voltage-dependent transitions during channel activation. The transitions underlying rapid L-channel activation may reflect rapid transitions of the voltage sensor used to trigger the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum during excitation-contraction coupling.

Skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs) play a pivotal role in the process by which excitation of the sarcolemma causes the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), ultimately resulting in muscle contraction (excitation-contraction (EC) coupling). Skeletal muscle DHPRs are low conductance L-type Ca2+ channels (L-channels; Dirksen & Beam, 1995, 1996) that are characterized by extremely slow activation kinetics, requiring more than 100 ms to open fully (Tanabe et al. 1990). Because of this slow activation and the brief duration of the skeletal muscle action potential, it is unlikely that significant Ca2+ enters the sarcoplasm through skeletal DHPRs during a single twitch. Rather, skeletal muscle DHPRs are postulated to act as voltage sensors for EC coupling by providing a mechanical link between sarcolemmal depolarization and the release of Ca2+ from the SR (Schneider & Chandler, 1973; Rios & Brum, 1987).

Skeletal muscle DHPRs support two kinetically distinct functions: (1) rapid, voltage-driven conformational changes that control the opening of nearby SR calcium release channels (voltage sensor function) (Rios & Brum, 1987) and (2) a rate-limiting transition(s) that results in slow activation of a voltage-gated L-channel (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992; Ma et al. 1996; Dirksen & Beam, 1996; Sipos et al. 1997). Based on estimates of the number of voltage sensors and calcium channels in frog skeletal muscle (Schwartz et al. 1985), the two functions of the skeletal DHPR have been suggested to be carried out by two separate populations of DHPRs. However, both functions (sensor and channel) are encoded by the same cDNA, since injection of dysgenic myotubes (which lack skeletal DHPRs) with skeletal muscle DHPR cDNA restores intramembrane charge movement, EC coupling, and L-type Ca2+ currents (Adams et al. 1990; Tanabe et al. 1990). In addition, the recent characterization of a component of intramembrane charge movement that reflects L-channel activation provides further support for the notion that skeletal muscle DHPRs function simultaneously as both voltage sensors and L-type Ca2+ channels (Dirksen & Beam, 1999).

The possibility of a dual function skeletal DHPR is also supported by the observation that L-channels in frog skeletal muscle are capable of fast conformational changes in response to membrane depolarization (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992; Garcia et al. 1990). These studies demonstrated that brief depolarizing conditioning pulses sufficient to open L-channels accelerate subsequent channel activation. Thus, frog skeletal L-channels undergo rapid gating transitions which may reflect the transitions that normally gate SR Ca2+ release (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992). The activation rate of purified rabbit skeletal muscle DHPRs incorporated into planar lipid bilayers is also accelerated following strong conditioning prepulses (Ma et al. 1996). However, prepulse-induced rapid channel gating is not observed in either rat cut fibres (Delbono, 1992) or cultured human myotubes (Sipos et al. 1997). The presence of this and other functional differences between skeletal DHPRs in intact frog and mammalian skeletal muscle (see Discussion) suggests that L-channels operate via different kinetic mechanisms in mammalian and amphibian skeletal muscle (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992; Dirksen & Beam, 1996; Sipos et al. 1997). Nevertheless, if the mammalian skeletal DHPR acts simultaneously as both a voltage sensor for EC coupling and a Ca2+-permeable L-channel, mammalian DHPRs must also exhibit rapid conformational changes in response to membrane depolarization.

The aim of this study was to develop a protocol that could demonstrate rapid activation of L-type Ca2+ current recorded from cultured mouse skeletal myotubes. Our results indicate that L-channel activation kinetics are greatly accelerated following prolonged depolarizations (60 s to +40 mV) and a brief recovery interval (3-10 s at -80 mV). The voltage dependence and DHP sensitivity of the accelerated currents confirmed that these currents originate from L-type Ca2+ channels operating in a rapid gating mode. The accelerated L-currents were characterized by an overall increase in the relative contribution of an intrinsic, rapidly activating component that typically comprises only a minor fraction of the total current observed in the absence of prolonged depolarization (Caffrey, 1994; Avila & Dirksen, 2000). Our results demonstrate that slowly activating L-channels are capable of producing rapid, voltage-dependent gating transitions, which would be required for these proteins to also couple membrane depolarization to SR Ca2+ release. Preliminary accounts of these findings have appeared in abstract form (O’Connell & Dirksen, 2000).

METHODS

Preparation of normal and dyspedic myotubes

Primary cultures of myotubes were prepared from skeletal muscle of newborn normal and dyspedic mice as described previously (Nakai et al. 1996; Avila & Dirksen, 2000). All animals were housed in a pathogen-free area at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry (URSMD). Animals were anaesthetized and decapitated by procedures that were reviewed and approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources at URSMD. All experiments were done 7-11 days after plating of myoblasts and were performed at room temperature.

Measurements of macroscopic calcium currents

Ionic currents were measured using the whole cell variant of the patch clamp technique. Patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass and had resistances of 1.5-2.0 MΩ when filled with the internal solution (see below). Currents were recorded with either a Dagan 3900A (Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN, USA) or Axopatch 200A (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) amplifier and filtered at 2 kHz by a four-pole Bessel filter. Data were digitized at 10 kHz using a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments) and analysed using the pCLAMP (Axon Instruments) and SigmaPlot (SPSS Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA) software suites. Linear capacitative currents were minimized (>90 %) using the capacitative transient cancellation feature of the amplifier. The remaining linear components were subtracted using a -P/3 leak subtraction protocol given either prior to (Fig. 1) or following (conditioning pulse experiments) each test pulse. The activation kinetics of accelerated L-currents were similar whether leak pulses were delivered before the conditioning depolarization or after the test pulse, indicating that the membrane properties were stable following prolonged depolarization. The average membrane capacitance for all experiments was 261 ± 15 pF, n = 91 and the average series (access) resistance (Rs) after compensation was 1.2 ± 0.04 MΩ (n = 91). The voltage error due to series resistance (Ve = RsICa) was always less than ∼5 mV. The average time constant for charging the membrane capacitance (τm = RsCm) was 0.32 ± 0.02 ms (n = 91) and was never larger than 0.88 ms. All data are presented as means ± s.e.m.

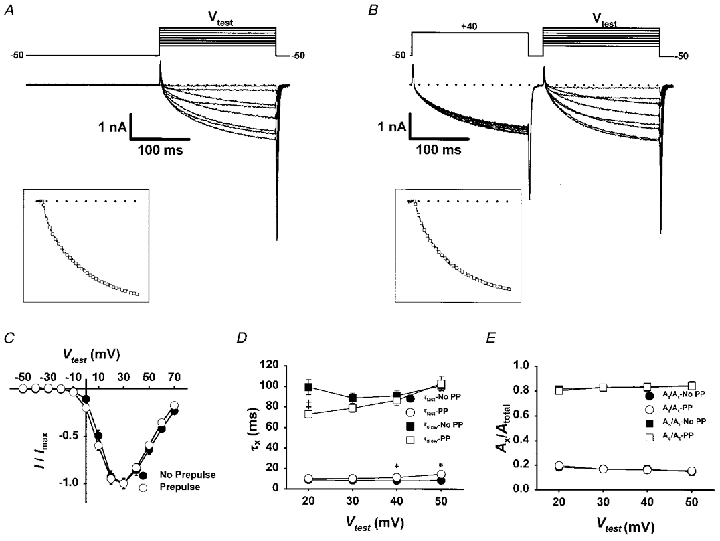

Figure 1. Brief depolarizing conditioning prepulses do not alter the activation properties of L-currents elicited by subsequent depolarization.

Representative traces in the absence of (A) and following a conditioning prepulse (B) consisting of a 200 ms depolarization to +40 mV and a 25 ms repolarization to -50 mV (to allow for complete L-channel deactivation). The effect of the prepulse was studied for test pulses from -50 to +70 mV in 10 mV increments (Vtest). Insets, representative L-currents elicited at +40 mV were fitted according to a second-order exponential function (□, superimposed over the data), as described in Methods. C, I-V relationships of L-currents elicited in the absence of (•) and following (○) the conditioning protocol. Currents are normalized to the peak current (30 mV) in each test pulse. D, the fast (τfast, circles) and slow (τslow, squares) time constants for L-currents elicited in the absence (filled symbols) or presence (open symbols) of a conditioning prepulse are plotted for test potentials between 20 and 50 mV (*P < 0.01). E, the fractional contribution of the fast (Afast/Atotal, circles) and slow (Aslow/Atotal, squares) components of the total L-current elicited in the absence (filled symbols) or presence (open symbols) of the conditioning prepulse are plotted for test potentials between 20 and 50 mV.

L-currents were elicited following inactivation of T-type Ca2+ channels using a 200 ms prepulse to -20 mV and a 25 ms repolarization to -50 mV (Adams et al. 1990; Dirksen & Beam, 1995) prior to each test pulse. Peak inward Ca2+ currents were assessed at the end of 200 ms test pulses of variable amplitude and plotted as a function of the membrane potential (pulse I–V curves). Pulse I–V curves were subsequently fitted according to:

| (1) |

where Vrev is the extrapolated reversal potential of the calcium current, V is the membrane potential during the pulse, I is the peak current during V, Gmax is the maximum L-channel conductance, VG1/2 is the voltage for half-activation of Gmax and kG is a slope factor. Thus, the values of Gmax, Vrev, VG1/2, and kG were generated as free parameters in eqn (1). The activation phase of macroscopic pulse currents was fitted as described previously (Avila & Dirksen, 2000) using the following two-exponential function:

| (2) |

where I(t) is the current at time t after the depolarization, Afast and Aslow are the steady-state current amplitudes of each component with τfast and τslow their respective time constants of activation, and C represents the steady-state peak current. In all cases, artifacts introduced by the declining phase of the gating current transient were minimized by beginning the fitting at the zero current level, which corresponded to 5-7 ms after the initiation of the voltage pulse (>10 × τm). Additionally, L-currents were recorded before and after ionic current blockade by the addition of 0.5 mM Cd2+ and 0.2 mM La3+. The residual currents were subsequently subtracted from raw current traces to generate ‘gating current-free’ L-currents. Control and ‘gating current-free’ L-currents exhibited similar activation kinetics (data not shown). Thus, the fast component of L-current activation is not greatly influenced by either the time required to charge the membrane capacitance or the declining phase of the gating current transient (Avila & Dirksen, 2000).

Recording solutions

For all measurements the internal solution consisted of (mM): 140 caesium aspartate, 10 Cs2-EGTA, 5 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4 with CsOH). The external solution contained (mM): 145 TEA-Cl, 10 CaCl2, 0.003 TTX (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) and 10 Hepes (pH 7.40 with TEA-OH). Dihydropyridine-sensitive currents were isolated following addition of 3 μM nifedipine to the external solution.

RESULTS

Brief conditioning depolarizations fail to alter the activation kinetics of L-type Ca2+ channels in mouse skeletal myotubes

The activation kinetics of L-type Ca2+ channels in frog skeletal muscle are transiently accelerated following conditioning depolarizations that are sufficient to open channels (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992; Garcia et al. 1990). However, similar conditioning prepulses fail to alter subsequent L-current activation in either intact rat cut fibres (Delbono, 1992) or cultured human myotubes (Sipos et al. 1997). Similar to these mammalian preparations, we failed to observe a marked change in L-current activation kinetics in cultured mouse skeletal myotubes following brief (200 ms) conditioning depolarizations (Fig. 1). Slowly activating L-currents were elicited every 10 mV from -50 to +70 mV either in the absence of (Fig. 1A) or following a 200 ms conditioning pulse to +40 mV (Fig. 1B). As illustrated in Fig. 1A-C, the 200 ms conditioning pulse did not greatly alter the magnitude, voltage dependence, or overall kinetics of L-type Ca2+ currents activated by subsequent test pulses. L-channel kinetics were not altered even after systematic changes in the level or duration of the interpulse potential, providing that these conditions ensured complete channel deactivation (data not shown).

We used two-exponential fitting to determine quantitatively the effects of brief depolarizing conditioning pulses on the amplitudes and time constants of L-channel activation (see also Avila & Dirksen, 2000). Brief depolarizing prepulses failed to greatly alter either the time constants of activation (τfast or τslow, Fig. 1D) or amplitudes (Afast or Aslow, Fig. 1E) of the two components of L-current activation (Fig. 1C and D). In addition, conditioning depolarization failed to alter (P > 0.3) the relative contribution of either the fast (Afast/(Afast + Aslow) or Afast/Atotal) or slow (Aslow/ (Afast + Aslow) or Aslow/Atotal) amplitudes that comprise the total L-current (Fig. 1D). For example, for test pulses to +40 mV, Afast/Atotal was similar in both the absence (0.24 ± 0.05, where Afast = 1.8 ± 0.3 pA pF−1, n = 12) and following the 200 ms conditioning depolarization (0.22 ± 0.04, where Afast = 1.4 ± 0.2 pA pF−1, n = 12). Similar results were obtained at every potential between +20 and +50 mV.

L-channel activation kinetics are not altered following recovery from short-term inactivation

Although prior channel opening did not accelerate subsequent channel activation, we tested whether L-channel activation might be altered following recovery from inactivation. The kinetics of inactivation and restoration from inactivation of L-channels have been rigorously examined in cultured human (Morrill et al. 1998; Harasztosi et al. 1999) and mouse skeletal myotubes (Gonzalez et al. 1995; Strube et al. 2000). These studies demonstrated that skeletal L-channel inactivation is a slow (∼2 s at +40 mV) and voltage-dependent process. We have observed similar results in cultured mouse myotubes (e.g. at +40 mV, τinact = 2.1 ± 0.7 s, n = 13).

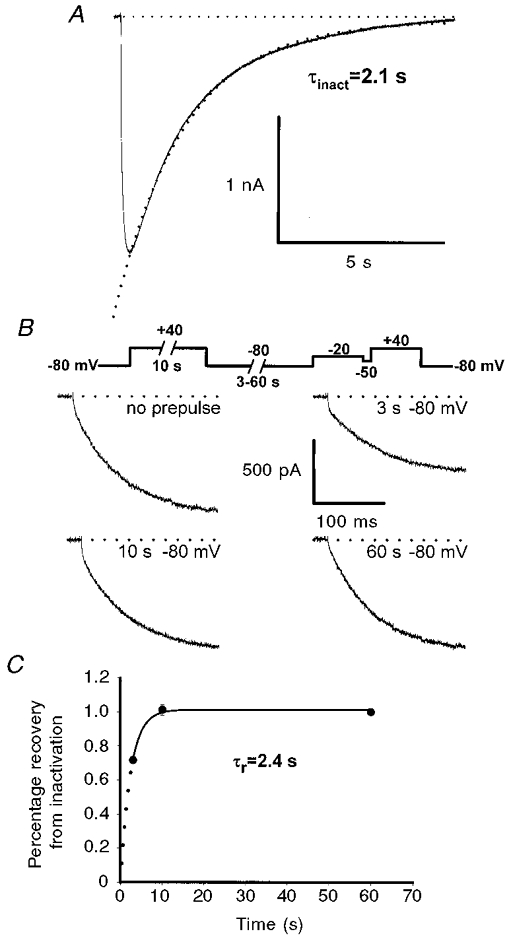

We explored the effects of channel inactivation on the rate of subsequently restored (or ‘reprimed’) L-channel kinetics using the voltage protocol illustrated in Fig. 2B. During this protocol, myotubes were depolarized to +40 mV for 10 s (‘short-term inactivation’), and subsequently reprimed at -80 mV for various intervals (3, 10, or 60 s). Figure 2B illustrates test pulse currents (200 ms test pulses to +40 mV) for control and following a 10 s inactivating prepulse and one of the three different repriming intervals. As anticipated, the magnitude of the test currents following inactivation was strongly dependent upon the repriming interval (Fig. 2C). On average, the magnitude of the L-current following the 60 s repriming interval was 98 ± 2 % (n = 8) of that of the control current. No difference was found in the magnitude of L-current restored between 10 and 60 s repriming intervals (Fig. 2C). Thus, our results are similar to those reported for human myotubes (see Fig. 6 in Harasztosi et al. 1999) in that restoration from short-term inactivation of L-current at -80 mV is comparable for repriming intervals between 10 and 60 s.

Figure 2. Depolarizations sufficiently long to inactivate L-channels fail to alter the activation kinetics of the L-currents elicited by subsequent depolarization.

A, L-currents were elicited by 10 s depolarizations to +40 mV. Inactivation was fitted by a single exponential function (dotted curve, τinact = 2.1 ± 0.7 s, n = 9). Due to the length of the test pulses used to determine the time course of inactivation, leak subtraction was not used for the data shown in A. B, representative L-currents recorded either in the absence of a prepulse (upper left) or following recovery from inactivation induced by a 10 s prepulse to +40 mV. Following inactivation, L-currents were reprimed at -80 mV for 3 s (upper right), 10 s (lower left), or 60 s (lower right). Outward gating current transients have been truncated for clarity. C, time dependence of L-current repriming at -80 mV following a 10 s depolarization to +40 mV.

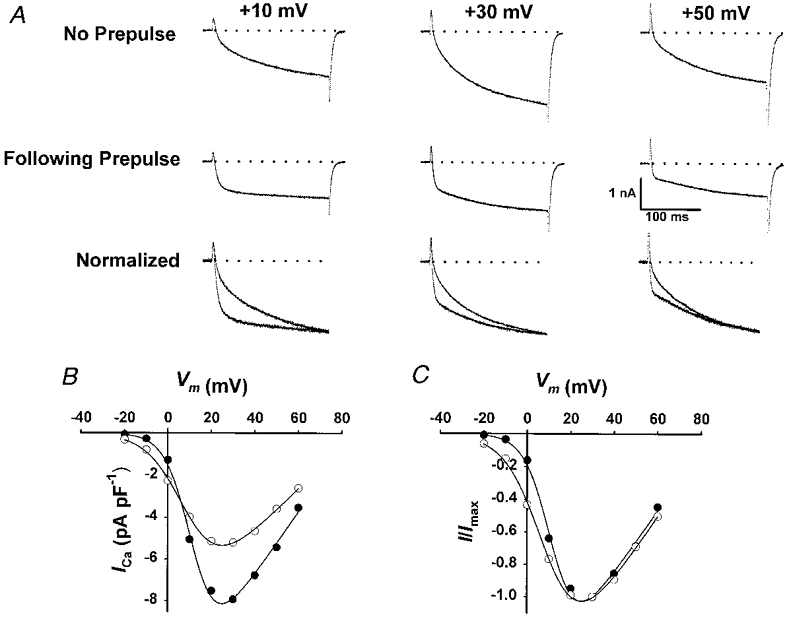

Figure 6. Acceleration of L-channel activation kinetics is voltage dependent.

A, data obtained for test pulses to +10, +30 and +50 mV are shown in the absence of a prepulse (top row), following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization (60 s +40 mV/10 s -80 mV, middle row), and after normalization to the control current recorded at +30 mV (bottom row). Tail currents have been truncated for clarity. B, peak I–V relationships of control and accelerated L-currents obtained from the experiment shown in A. Fitting the I–V data for multiple experiments to eqn (1) yielded the following average values (n = 6): for control, Gmax = 221 ± 13 nS nF−1, VG1/2 = 14.0 ± 1.0 mV and kG = 5.7 ± 0.2 mV; for 10 s repriming, Gmax = 140 ± 16 nS nF−1 (P < 0.01), VG1/2 = 12.3 ± 0.8 mV and kG = 8.1 ± 0.3 mV (P < 0.001). C, I–V curves shown in B normalized to the peak current value recorded in the absence of prolonged depolarization.

The degree of L-current restoration appeared to have little effect on subsequent L-channel activation kinetics. Following short-term (10 s) inactivation, reprimed L-channels exhibited activation kinetics that were similar to those of the control current (Fig. 2B). Thus, the recovery of L-channels from short-term inactivation is likely to be mediated via a pathway that ensures the return of channels to their original resting state upon repolarization.

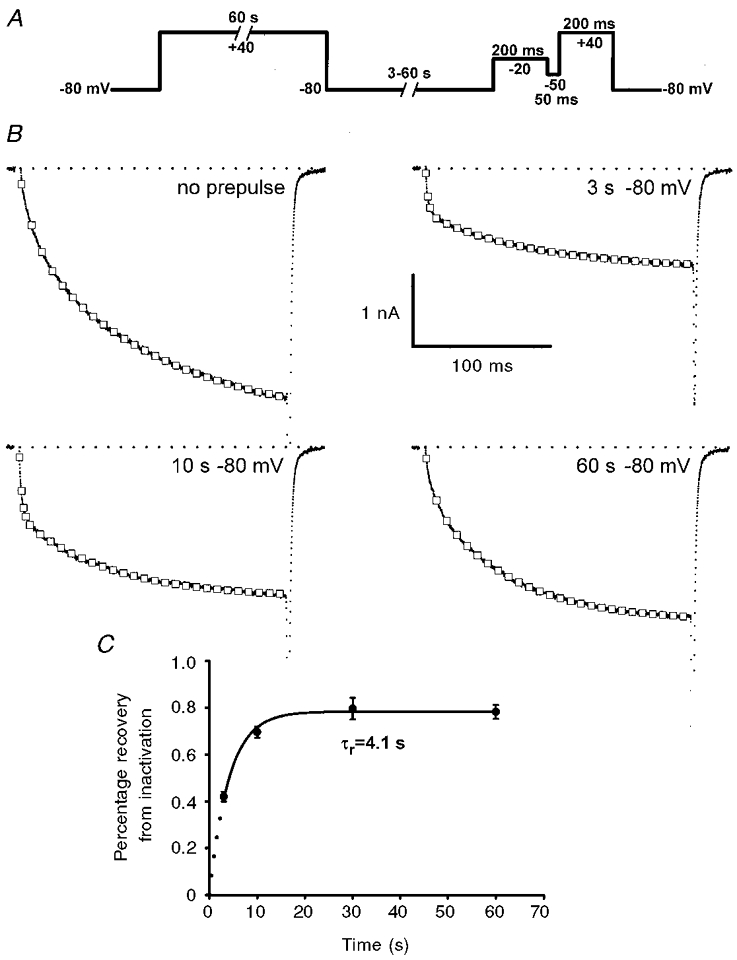

Acceleration of L-channel activation kinetics following recovery from prolonged depolarization

Nilius et al. (1994) demonstrated that inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle is ‘history dependent’, such that prolonged depolarization promotes channel entry into a kinetically distinct inactivation state. Thus, we investigated the effects of prolonged depolarization on subsequent L-channel activation kinetics in skeletal myotubes. Using the protocol depicted in Fig. 3A, L-currents were elicited following prolonged depolarization (60 s to +40 mV) followed by a variable (3, 10, 30 or 60 s) repriming interval at -80 mV. Representative L-type Ca2+ currents elicited by test pulses to +40 mV are illustrated in Fig. 3B. Control L-currents, obtained in the absence of prolonged depolarization, displayed the typical slow activation kinetics of the skeletal L-channel (Fig. 3B, top left). L-currents only partially recovered following a 3 s repriming interval after prolonged depolarization (Fig. 3B, top right). However, L-currents recorded following the 3 s repriming interval exhibited a remarkably accelerated overall rate of channel activation and were characterized by a clearly biphasic time course of channel activation. Not surprisingly, the magnitude of the reprimed current was substantially increased (∼2-fold) following a 10 s repriming interval (Fig. 3B, lower left). Nevertheless, the current recorded following a 10 s repriming interval also exhibited a similar acceleration in overall channel activation. Prolonged depolarization produced a transient acceleration in L-channel gating, since the characteristic slow channel activation kinetics were restored following a 60 s repriming interval (Fig. 3B, lower right).

Figure 3. Recovery from prolonged depolarization is accompanied by an acceleration in L-channel activation kinetics.

A, voltage protocol used to investigate the effect of prolonged depolarization of L-channel activation kinetics. B, representative L-current recordings (200 ms to +40 mV) obtained for control (no prepulse, upper left) and after prolonged depolarization and repriming intervals of 3 s (upper right), 10 s (lower left) and 60 s (lower right). Gating and tail currents have been truncated for clarity. C, time dependence of L-current repriming at -80 mV following 60 s depolarization to +40 mV.

The time course for recovery of the peak L-current from prolonged depolarization is depicted in Fig. 3C. On average, the magnitude of the L-current restored following a 60 s repriming interval was 78 ± 3 % (n = 39) of that of the control current. Thus, a small component of the total L-current reprimes slower than our maximal repriming interval (60 s), although a minor contribution of channel rundown (∼5 % in 10 min) during the course of these experiments cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, the majority of L-current is restored following repriming intervals of 10 s or longer. The data in Fig. 3 indicate that fast channel gating does not arise from a selective repriming of the fast component of control L-current activation since overall channel kinetics were independent of peak amplitude (compare L-currents following 3, 10 and 60 s repriming intervals; see also Discussion). Rather, the data support the notion that prolonged depolarization promotes the conversion of slowly activating channels to a rapidly activating gating pattern and that conversion back to the channel’s original resting state occurs only slowly at -80 mV.

The biphasic nature of the accelerated currents is clearly well described by fitting current activation to the sum of two exponential components (see Fig. 3B). This analysis revealed that the acceleration of L-current activation following prolonged depolarization involves both a reduction in the fast time constant (Fig. 4A) and an increase in the fractional contribution of the fast amplitude to the total current (Fig. 4B). For example, L-currents elicited following the 10 s repriming interval exhibited an ∼3-fold reduction in τfast (10.2 ± 1.1 ms, n = 60, and 3.0 ± 0.2 ms, n = 60, for control and 10 s repriming, respectively) and a nearly 2-fold increase in Afast/Atotal (0.24 ± 0.02 where Afast = 2.1 ± 0.2 pA pF−1, n = 60, and 0.40 ± 0.02 where Afast = 2.2 ± 0.1 pA pF−1, n = 60, for control and 10 s repriming, respectively). Similar results were observed for 3 s repriming intervals, though the magnitude of the total reprimed current was significantly reduced (see Fig. 3C). Prolonged depolarization did not significantly alter the value of the slow time constant of activation (τslow, Fig. 4A). The effects of prolonged depolarization were transient since the changes in τfast and the Afast/Atotal were reduced following longer repriming intervals (Fig. 4A and B). The degree of L-channel acceleration was similar in all myotubes used in this study (101 to 521 pF), regardless of their stage of development. The combined effect of a reduction in τfast and an increase in Afast/Atotal would be anticipated to increase Ca2+ influx during brief depolarizations (e.g. an action potential). Thus, we compared the relative contribution of the steady-state integral of the fast component of the current to the total steady-state integral (Intfast/Inttotal) for control and accelerated L-currents (Fig. 4C). Following brief repriming intervals (3 and 10 s), Intfast/Inttotal was significantly enhanced (P < 0.001) compared to that of the control L-current. This increase was less significant (P < 0.01) following longer repriming intervals (30 s) and insignificant (P > 0.2) after 60 s repriming intervals (Fig. 4C).

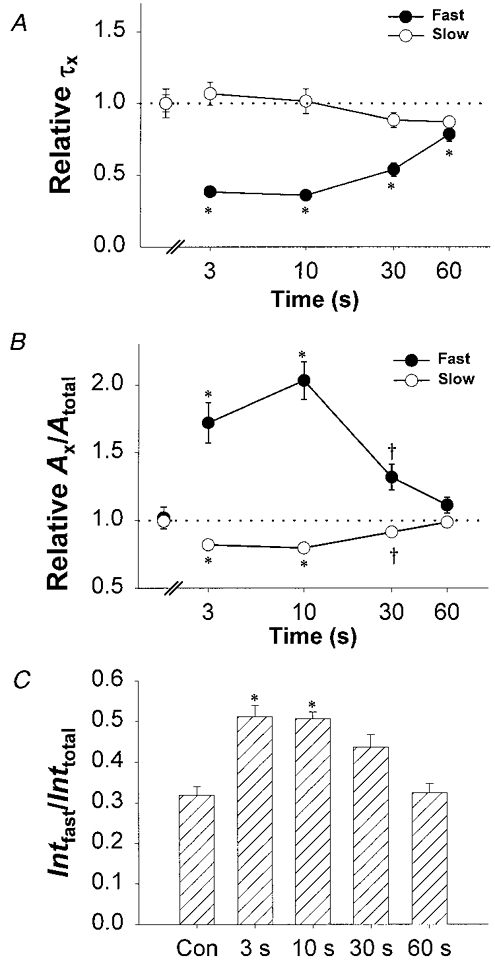

Figure 4. Kinetic parameters of accelerated L-current.

A, effects of the repriming duration (3, 10, 30 and 60 s) on the mean relative values of τfast (•) and τslow (○). Values of relative τfast and τslow for each repriming duration were obtained by dividing by the corresponding value obtained in the absence of a prepulse (control: τfast = 9.7 ± 0.8, n = 60; and τslow = 88.6 ± 4.1, n = 60). Normalized control values are shown for comparison to the left of the break in the abscissa. Prolonged depolarization caused a significant (P < 0.001) reduction in relative τfast, but not relative τslow. B, effects of the repriming interval (3, 10, 30 and 60 s) on the mean relative values of Afast/Atotal (•) and Aslow/Atotal (○). Values of Afast/Atotal and Aslow/Atotal for each repriming interval were obtained by dividing by the corresponding value obtained in the absence of a prepulse (control: Afast/Atotal = 0.23 ± 0.02, n = 60; and Aslow/Atotal = 0.77 ± 0.02, n = 60). Normalized control values are shown for comparison to the left of the break in the abscissa. Prolonged depolarization caused significant alterations in relative Afast/Atotal and relative Aslow/Atotal at P < 0.001 (*) for 3 and 10 s repriming intervals and P < 0.01 (†) for the 30 s repriming interval. C, L-currents elicited following prolonged depolarization and brief repriming intervals (3 and 10 s) exhibit a significant (* P < 0.001) increase in the fractional contribution of the steady-state integral of the fast component of the current (Intfast/Inttotal).

The rapidly activating currents originate from DHP-sensitive L-channels

In order to determine whether the fast component of current seen after prolonged depolarization is mediated via L-channels, L-currents were recorded before and after the addition of dihydropyridine antagonist. If the fast component of current induced by prolonged depolarization arises from acceleration in L-current activation, rather than from recruitment of either leak or DHP-insensitive channels, then the accelerated current should be blocked by nifedipine. Figure 5 illustrates the effects of nifedipine (3 μM) on test currents elicited in the absence and following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization. In the absence of a conditioning prepulse, a 200 ms test pulse to +40 mV induced a typical, slowly activating L-current that was blocked 99 ± 2 % (n = 8) upon addition of 3 μM nifedipine (Fig. 5A). The DHP-sensitive L-current exhibited similar overall activation kinetics to those observed in the absence of DHP. Specifically, both the total and DHP-sensitive currents exhibited similar values for Afast/Atotal (0.23 ± 0.06, where Afast = 2.1 ± 0.6 and 1.9 ± 0.5 pA pF−1, n = 8, for both total and DHP-sensitive control currents, respectively), τfast (8.1 ± 0.6 and 10.5 ± 0.8 ms, n = 8, for total and DHP-sensitive control currents, respectively) and τslow (74.3 ± 6.1 and 82.7 ± 9.6 ms, n = 8, for total and DHP-sensitive control currents, respectively). Accelerated test pulse currents elicited following prolonged depolarization and a 10 s repriming interval (at -80 mV) were also entirely blocked upon addition of 3 μM nifedipine (Fig. 5B). Total and DHP-sensitive currents elicited following prolonged depolarization were each characterized by an increase in Afast/Atotal (0.39 ± 0.04, where Afast = 2.6 ± 0.4 pA pF−1, and 0.40 ± 0.03, where Afast = 2.4 ± 0.3 pA pF−1, n = 8, for total and DHP-sensitive accelerated currents, respectively) and a reduction in τfast (2.8 ± 0.5 and 3.6 ± 0.4 ms, n = 8, for total and DHP-sensitive accelerated currents, respectively) without an alteration in τslow (68.0 ± 5.1 and 62.8 ± 2.5 ms, n = 8, for total and DHP-sensitive accelerated currents, respectively). The data in Fig. 5 demonstrate that the test currents that were accelerated following brief recovery from prolonged depolarizations originate from DHP-sensitive Ca2+ channels.

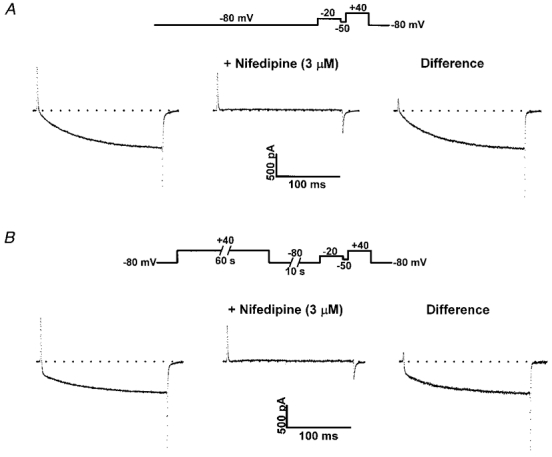

Figure 5. Accelerated currents are sensitive to block by dihydropyridine antagonist.

A, control currents (no prepulse) recorded in the absence (left) and presence (middle) of nifedipine (3 μM). DHP-sensitive control currents (right) exhibited slow activation kinetics typical of skeletal L-currents. B, accelerated currents (60 s +40 mV, 10 s repriming to -80 mV) recorded in the absence (left) and presence (middle) of nifedipine (3 μM). DHP-sensitive currents (right) exhibited accelerated activation kinetics following brief recovery (10 s at -80 mV) from prolonged depolarization.

Voltage dependence of accelerated skeletal L-current

Figures 3–5 demonstrate the effects of prolonged depolarization on subsequent L-channel activation elicited at +40 mV, a potential at which L-channel conductance is maximal (Avila & Dirksen, 2000). We have also characterized the effects of prolonged depolarization on L-channel activation over a broad range of potentials (Figs 6 and 7). In the absence of a conditioning prepulse, the values of τfast and τslow were nearly independent of voltage at test potentials between +20 and +50 mV (see Fig. 1D). However, L-channel activation kinetics elicited by weak depolarization (∼0 mV) are characterized by a greater contribution of Afast to the total current (at +0 mV, Afast/Atotal = 0.40 ± 0.04, n = 3; see also Caffrey, 1994; Avila & Dirksen, 2000), while Afast/Atotal plateaus at ∼0.20 for more depolarized voltages (Fig. 1E). Thus, the degree of L-current acceleration observed upon recovery from prolonged depolarization may also be voltage dependent.

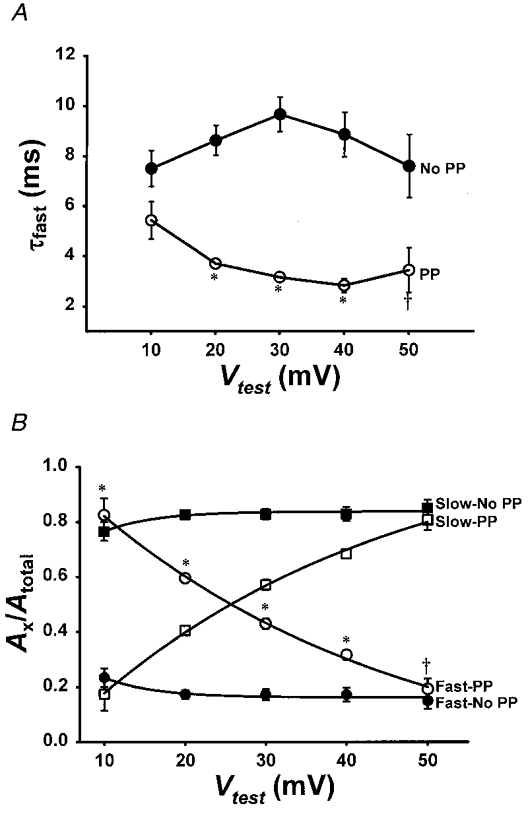

Figure 7. Prolonged depolarization reduces τfast and shifts the voltage dependence Afast/Atotal.

A, voltage dependence of τfast for L-currents obtained in the absence of a prepulse (•) and following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization (○). No change in τslow was observed (data not shown). B, fractional contribution of the fast (Afast/Atotal) and slow (Aslow/Atotal) components for control and accelerated L-currents is plotted versus test potential. *P < 0.001 and *P < 0.01.

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of test pulse potential on L-current activation kinetics of control and accelerated L-channels. In the absence of a conditioning prepulse, L-current magnitude varies with voltage while the overall activation kinetics are slow over a broad voltage range (Fig. 6A, top row). L-currents elicited following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization were similar to the control currents in both magnitude and voltage dependence (Fig. 6A, middle row). However, the reprimed L-currents each exhibited markedly accelerated kinetics of activation. Moreover, the acceleration of the reprimed currents was most striking at more negative voltages, as emphasized by normalization of the data (Fig. 6A, bottom row). In fact, the reprimed L-currents elicited at +10 mV were nearly entirely rapidly activating, similar to that observed for cardiac L-current expressed in dysgenic myotubes (Tanabe et al. 1991).

L-currents elicited in the absence of a prepulse and following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization each exhibited the classic U-shaped voltage dependence, a hallmark of L-channels (Fig. 6B and C). However, the L-channels restored during this repriming interval exhibited a slight reduction (P < 0.001) in their voltage dependence of channel activation (from Boltzmann fitting of the data, kGwas 5.7 ± 0.2 and 8.1 ± 0.3 mV, n = 6, for control and reprimed currents, respectively). At test potentials between +20 and +50 mV, the reprimed L-currents exhibited both a significant reduction in τfast (Fig. 7A) and an increase in the fractional contribution of Afast to the total current (Fig. 7B). However, the greater acceleration of the reprimed L-currents observed at negative potentials (e.g. +10 mV) arises primarily from a marked enhancement in Afast/Atotal (0.24 ± 0.03, n = 6, and 0.83 ± 0.06, n = 6, for control and accelerated L-currents, respectively, at +10 mV). At more depolarized potentials, the contribution of Afast decreased but remained larger than the corresponding value obtained for control currents (Fig. 7B). Over the range of potentials studied (+10 to +50 mV), Afast/Atotal decreased continually (e-fold ∼38 mV) as the test potential became more depolarized. These data suggest that acceleration of L-current activation by prolonged depolarization involves a large shift (∼40 mV) in the intrinsic voltage dependence of Afast/Atotal.

Acceleration by prolonged depolarization does not require L-channel interaction with RyR1

The signalling that occurs between the DHPR and RyR1 in skeletal muscle is reciprocal since the presence of RyR1 modifies several fundamental L-channel properties including conductance (Nakai et al. 1996), activation (Nakai et al. 1996; Fleig et al. 1996; Avila & Dirksen, 2000), expression level, DHP responsiveness, and relative conductance to Ba2+ and Ca2+ ions (Avila & Dirksen, 2000). Since L-channel activation in normal myotubes is slower than that of dyspedic myotubes which lack RyR1 proteins (Nakai et al. 1996; Avila & Dirksen, 2000), it is possible that RyR1 retards L-channel activation and that prolonged depolarization disrupts this impediment to channel opening. Alternatively, the acceleration of L-channel kinetics by prolonged depolarization may be an intrinsic property of the L-channel that is independent of the interaction with RyR1. To test these two ideas, we characterized L-channel activation kinetics in dyspedic myotubes subjected to the prolonged depolarization protocol used in normal myotubes (as illustrated in Figs 3–7).

Figure 8A–D illustrates that L-currents recorded from dyspedic myotubes are also accelerated following brief recovery (10 s repriming interval at -80 mV) from prolonged depolarization (60 s +40 mV). For example, L-currents elicited following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization exhibited a striking increase in Afast/Atotal (Fig. 8C) and an increase in Intfast/Inttotal (Fig. 8D). Thus, prolonged depolarization produced qualitatively similar effects on L-channel activation kinetics even in the absence of an interaction with RyR1. These results indicate that conversion to a fast gating mode occurs even in the absence of RyR1 and, therefore, represents an intrinsic property of the skeletal L-type Ca2+ channel.

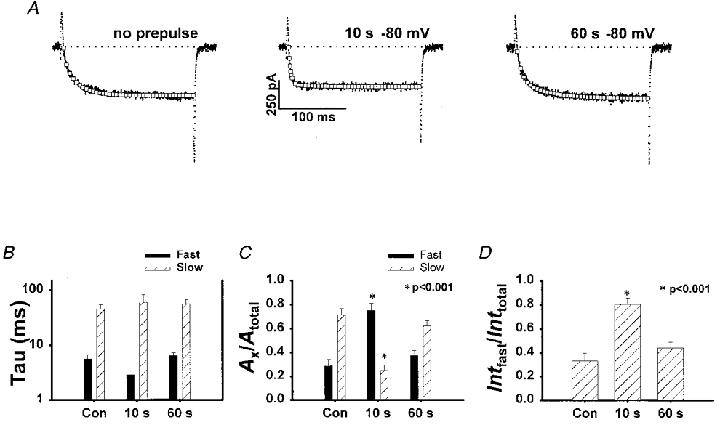

Figure 8. Prolonged depolarization-induced L-current acceleration does not depend on the presence of RyR1.

A, DHP-sensitive (3 μM nifedipine) L-currents (200 ms test pulse to +40 mV) recorded from a dyspedic myotube in control (no prepulse) and following recovery from prolonged depolarization (60 s to +40 mV). Repriming intervals of 10 and 60 s (at -80 mV) restored 80 ± 6 % (n = 7) and 94 ± 10 % (n = 7) of the control L-current, respectively. B, average effects of prolonged depolarization on τfast at +40 mV in dyspedic myotubes. C, average effects of prolonged depolarization on Afast/Atotal at +40 mV in dyspedic myotubes. The effect on Afast/Atotal at +40 mV in dyspedic myotubes was somewhat more pronounced than that observed in normal myotubes. D, average effects of prolonged depolarization on Intfast/Inttotal at +40 mV in dyspedic myotubes.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is the discovery and characterization of a novel protocol (brief recovery from prolonged depolarization) that accelerates the rate of L-channel activation in mouse skeletal myotubes. The voltage dependence and DHP sensitivity of the accelerated currents confirmed their L-channel origin. The degree of L-channel acceleration depended on the test pulse potential, such that acceleration was greater at less depolarized potentials. A reduction in τfast at all test potentials and an increase in the fractional contribution of Afast to the total L-current, particularly at less depolarized potentials, were the primary effects of prolonged depolarization. In spite of the influence of RyR1 on several essential properties of skeletal L-channels (Nakai et al. 1996; Fleig et al. 1996; Avila & Dirksen, 2000), L-currents were also accelerated following brief recovery from prolonged depolarization in dyspedic myotubes. These results are consistent with the notion that prolonged depolarization causes a transient alteration in the intrinsic gating properties of L-channels in mouse skeletal myotubes.

Species-dependent differences in skeletal L-type Ca2+ channels

Several important differences have been identified between L-channels recorded from amphibian and mammalian skeletal muscle. For example, the primary sequence of repeat I (Tanabe et al. 1991), and more specifically the sequence within repeat I of the S3 segment and the linker connecting the IS3 and IS4 segments, of the rabbit skeletal muscle DHPR is a critical determinant of the slow activation of mammalian skeletal L-channels (Nakai et al. 1994). However, the corresponding sequence within repeat I does not account for slow L-channel activation of DHPRs from either frog (Zhou et al. 1998) or carp (Wang et al. 1995) skeletal muscle. The presence of distinct protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation sites in rabbit and frog DHPR primary sequences has been suggested to account for fundamental differences in regulation between mammalian and amphibian skeletal muscle DHPRs (Zhou et al. 1998). Finally, two distinct components of intramembrane charge movements (Qβ and Qγ) are observed in frog, but not mammalian skeletal muscle (see Melzer et al. 1995 for review). In frog skeletal muscle, Qβ has been hypothesized to represent the voltage sensor gating current that triggers SR Ca2+ release with Qγ representing an additional component arising from an increase in local potential introduced by local changes in intracellular [Ca2+] (Pizarro et al. 1991). The absence of a resolvable Qγ component in charge movement measurements obtained from mouse myotubes represents another fundamental difference between DHPR function in frog and mouse skeletal muscle.

The extremely slow and weakly voltage-dependent rate of channel activation, coupled with a rapid and strongly voltage-dependent rate of channel deactivation, is a hallmark of skeletal muscle L-channels. Although L-channels recorded from frog, rabbit, rat, mouse and human skeletal muscle each exhibit this general kinetic profile, a single kinetic model of L-channel activation is unable to account for important species-dependent differences. For example, brief conditioning prepulses accelerate subsequent L-channel activation in frog skeletal muscle (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992), but not human (Sipos et al. 1997), rat (Delbono, 1992), or mouse myotubes (Fig. 1). Thus, fundamentally distinct kinetic models are required to account for L-channel activation in frog (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992) and mammalian (Dirksen & Beam, 1996; Francini et al. 1996; Ma et al. 1996; Sipos et al. 1997) muscle.

Possible mechanisms of L-channel acceleration induced by prolonged depolarization

Vascular smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels exhibit a striking delay in channel recovery from inactivation following prolonged conditioning prepulses, suggesting the entry of channels into distinct inactivation states following progressive channel inactivation (Nilius et al. 1994). Our data indicate that L-channel recovery from inactivation in skeletal myotubes is also ‘history dependent’, such that channel recovery is slowed following progressive inactivation (compare τr in Figs 2C and 3C). Since acceleration is not observed following short-term inactivation (Fig. 2), recovery from ‘proximal’ inactivation states must occur via a pathway that ensures the return of channels to their original resting state. Thus, L-channel inactivation per se is insufficient to alter subsequent channel activation. Rather, only prolonged depolarization, and presumably entry into deep inactivation states, is capable of inducing a transient kinetic transformation in the channel.

A selective or preferential repriming of Afast could provide a potential mechanism of transient L-channel acceleration following prolonged depolarization. However, our data argue against a preferential repriming of Afast compared to Aslow. First of all, the magnitude of Afast/Atotal is similar for test potentials between +10 and +50 mV in the absence of a prepulse. Thus, a simple preferential repriming of Afast could not account for the difference in Afast/Atotal observed over this voltage range following prolonged depolarization (Fig. 7). Secondly, at certain voltages the absolute magnitude of Afast is actually larger (P < 0.001) following prolonged depolarization than that observed under control conditions (at +20 mV, Afast was 1.8 ± 0.2 and 2.8 ± 0.2 pA pF−1, n = 14 for control and accelerated L-currents, respectively). Finally, the degree of acceleration does not correlate with the level of channel repriming. For example, acceleration is similar following 3 and 10 s restoration intervals in spite of a nearly 2-fold difference in the magnitude of reprimed current. Conversely, although the magnitude of reprimed current is similar following 10 and 60 s restoration intervals, only the longer repriming interval is sufficient to restore L-channels to their overall slow gating pattern (see Fig. 3B). The voltage dependence and DHP sensitivity of the accelerated currents rules out a contribution of rapidly activating T-type Ca2+ channels to the accelerated current. Thus, our data indicate that prolonged depolarization alters the intrinsic gating pattern of skeletal L-channels, particularly at less depolarized potentials.

Skeletal L-type Ca2+ channels are potentiated in response to both single conditioning depolarizations (50-200 ms) and trains of prepulses designed to mimic forceful tetanic contractions triggered by action potentials delivered at high frequency (Sculptoreanu et al. 1993). Skeletal L-channel potentiation arises from rapid phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and is characterized by an ∼15 mV hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of channel activation, an acceleration in the kinetics of channel activation, and a slowing (up to 9-fold) of channel deactivation (Sculptoreanu et al. 1993; Johnson et al. 1994, 1997). However, it is unlikely that the changes in L-channel activation kinetics induced by prolonged depolarization in our study represent a similar PKA-mediated mechanism of L-channel potentiation. First of all, since the presence of intracellular ATP is an absolute requirement for voltage-dependent L-channel potentiation (Johnson et al. 1994), the exclusion of ATP from our internal pipette solution should have eliminated this regulatory pathway in our experiments. In addition, L-channels accelerated following prolonged depolarization exhibited neither a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of channel activation (see Fig. 6C) nor a slowing in channel deactivation (see Fig. 5 for example). Thus, the conversion of slow to rapid channel gating promoted by prolonged depolarization in our experiments appears to involve a mechanism that is distinct from PKA-mediated potentiation of skeletal L-channels.

The effect of prolonged depolarization on L-current activation may involve an alteration in the intrinsic gating mechanism of the channel. L-current activation in skeletal myotubes requires the sum of two exponential terms (Caffrey, 1994; Avila & Dirksen, 2000), suggesting the presence of two kinetically distinct pathways of skeletal L-current activation even under control conditions. Thus, bi-exponential activation could result from two separate L-channel populations (or gating modes), one that activates rapidly (generating τfast and Afast) and a second that activates slowly (generating τslow and Aslow). Under such a scenario, L-channel acceleration could occur under conditions that promote the conversion of slowly gating channels to rapidly gating channels. However, our data indicate that L-channels accelerated following prolonged depolarization are characterized by a shift in the voltage dependence of Afast/Atotal and a 2- to 3-fold reduction in τfast (Fig. 7). A large reduction in τfast is inconsistent with the notion that prolonged depolarization promotes a simple interconversion between two existing, yet kinetically distinct gating modes.

Alternatively, bi-exponential skeletal L-channel activation could result from two kinetically distinct pathways of channel activation within a single gating scheme (e.g. Bennett et al. 1985; Caffrey, 1994). For example, a kinetic model with multiple open states and proximal closed states has been proposed to describe the bi-exponential L-channel activation kinetics in BC3H1 cells (Caffrey, 1994). In such a model, L-channel acceleration could arise from an increase in the forward rate constants governing the rapidly activating pathway of channel activation, thereby decreasing τfast and increasing Afast/Atotal. Although alterations within a single gating scheme could account for the effects of prolonged depolarization on L-channel activation kinetics, refining and distinguishing between specific kinetic models will require future experiments designed to characterize single channel currents and intramembrane charge movements of control and accelerated L-channels.

Implications of L-channel acceleration for skeletal muscle function

During a single twitch, skeletal muscle contraction does not depend on extracellular calcium (Armstrong et al. 1972). However, tetanic contractions triggered by high frequency action potentials are dependent upon extracellular Ca2+ and influx through voltage-gated L-channels (Kotsias et al. 1986). In addition, Ca2+ influx through skeletal L-channels has also been suggested to influence acetylcholine receptor (Shainberg et al. 1976) and DHPR (Renganathan et al. 1999) gene expression in skeletal muscle. Clearly, the conditions used in our study (60 s depolarizations to +40 mV at room temperature) are unlikely to occur under normal physiological conditions. It is currently unknown whether or not L-channel acceleration could also occur under certain physiological conditions (e.g. following tetanic stimuli at 37°C). If L-channel acceleration occurs under such conditions, it will be important to examine the possible role of increased Ca2+ influx on skeletal muscle EC coupling. For example, Ca2+ influx through accelerated L-channels could act locally at nearby SR Ca2+ release channels to sensitize or ‘fine-tune’ voltage-gated SR Ca2+ release.

The ability of brief conditioning prepulses to accelerate subsequent L-channel activation in frog skeletal muscle has been used as evidence that skeletal L-channels undergo rapid transitions prior to channel opening (Feldmeyer et al. 1990, 1992). Rapid conformational changes in response to membrane depolarization would be required in order for slowly activating L-type Ca2+ channels to also function as voltage sensors for EC coupling. Thus, the inability of similar brief conditioning prepulses to accelerate mammalian skeletal L-channel activation (but see also Ma et al. 1996) could potentially indicate that separate populations of DHPRs are needed to account for the two kinetically distinct DHPR functions. Although the mechanisms of slow channel activation are likely to qualitatively differ in amphibian and mammalian skeletal muscle, our results demonstrate that slowly activating mammalian skeletal muscle L-channels are also capable of undergoing rapid, voltage-dependent transitions en route to channel opening. Furthermore, these transitions may reflect rapid transitions of the voltage sensor that are used to trigger SR Ca2+ release during EC coupling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Kurt G. Beam and Paul D. Allen for providing us with the dyspedic mice used in this study. We would like to thank Guillermo Avila for many helpful discussions and for suggestions to improve the manuscript. We also thank Drs Ted Begenisich, Kevin Gingrich, and Claire Quinn for critical reading of the manuscript and Linda Groom for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (AR44657) and a Neuromuscular Disease Research grant.

References

- Adams BA, Tanabe T, Mikami A, Numa S, Beam KG. Intramembrane charge movement restored in dysgenic skeletal muscle by injection of dihydropyridine receptor cDNAs. Nature. 1990;346:569–572. doi: 10.1038/346569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM, Bezanilla FM, Horowicz P. Twitches in the presence of ethylene glycol bis(-aminoethyl ether)-N,N′-tetracetic acid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1972;26:605–608. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila G, Dirksen RT. Functional impact of the ryanodine receptor on the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel. Journal of General Physiology. 2000;115:467–479. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.4.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PB, McKinney LC, Kass RS, Begenisich T. Delayed rectification in the calf cardiac Purkinje fiber. Evidence for multiple state kinetics. Biophysical Journal. 1985;48:553–567. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83813-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey J. Kinetic properties of skeletal-muscle-like high threshold calcium current in a non-fusing muscle cell line. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;427:277–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00374535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbono O. Calcium current activation and charge movement in denervated mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:187–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen RT, Beam KG. Single calcium channel behavior in native skeletal muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1995;105:227–247. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen RT, Beam KG. Unitary behavior of skeletal, cardiac, and chimeric L-type Ca2+ channels expressed in dysgenic myotubes. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;107:731–742. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.6.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen RT, Beam KG. Role of calcium permeation in dihydropyridine receptor function: Insights into channel gating and excitation-contraction coupling. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;114:393–404. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Melzer W, Pohl B, Zollner P. Fast gating kinetics of the slow Ca2+ current in cut skeletal muscle fibres of the frog. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;425:347–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Melzer W, Pohl B, Zollner P. Modulation of calcium current gating in frog skeletal muscle by conditioning depolarization. The Journal of Physiology. 1992;457:639–653. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig A, Takeshima H, Penner R. Absence of Ca2+ current facilitation in skeletal muscle of transgenic mice lacking the type 1 ryanodine receptor. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:339–345. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francini D, Bencini C, Squecco R. Activation of L-type calcium channel in twitch skeletal muscle fibres of the frog. The Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:121–140. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, AvilaSakar AJ, Stefani E. Repetitive stimulation increases the activation rate of skeletal muscle Ca2+ currents. Pflügers Archiv. 1990;416:210–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00370245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Nakai J, Beam KG. Localization of a region in the cardiac L-type calcium channel important for divalent-dependent inactivation. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:A258. [Google Scholar]

- Harasztosi C, Sipos I, Kovacs L, Melzer W. Kinetics of inactivation and restoration from inactivation of the L-type calcium current in human myotubes. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:129–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.129aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Brousal JP, Peterson BZ, Gallombardo PA, Hockerman GH, Lai Y, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of the cloned skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel by anchored cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:1243–1255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01243.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Voltage-dependent potentiation of L-type Ca2+ channels in skeletal muscle cells requires anchored cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:11492–11496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsias BA, Muchnik S, ObejeroPaz CA. Co2+, low Ca2+, and verapamil reduce mechanical activity in rat skeletal muscles. American Journal of Physiology. 1986;250:C40–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.1.C40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Gonzalez A, Chen R. Fast activation of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels of skeletal muscle. Multiple pathways of channel gating. Journal of General Physiology. 1996;108:221–232. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, HerrmannFrank A, Luttgau H., Ch The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill JA, Brown RH, Cannon SC. Gating of the L-type Ca channel in human skeletal myotubes: An activation defect caused by the hypokalemic periodic paralysis mutation R528H. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:10320–10334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10320.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai J, Adams BA, Imoto K, Beam KG. Critical roles of the S3 segment and S3-S4 linker of repeat I in activation of L-type calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:1014–1018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai J, Dirksen RT, Nguyen HT, Pessah IN, Beam KG, Allen PD. Enhanced dihydropyridine receptor channel activity in the presence of ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1996;380:72–75. doi: 10.1038/380072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Kitamura K, Kuriyama H. Properties of calcium channel currents in smooth muscle cells of rabbit portal vein. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;426:239–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00374777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell KMS, Dirksen RT. Prolonged depolarization accelerates activation of the L-type Ca2+ current (L-current) in mouse skeletal myotubes. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:370A. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro G, Csernoch L, Uribe I, Rodriguez M, Rios E. The relationship between Q gamma and Ca release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1991;97:913–947. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.5.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renganathan M, Wang Z-M, Messi ML, Delbono O. Calcium regulates L-type Ca2+ channel expression in rat skeletal muscle cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1999;438:649–655. doi: 10.1007/s004249900087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios E, Brum G. Involvement of dihydropyridine receptors in excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987;325:717–720. doi: 10.1038/325717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF, Chandler WK. Voltage dependent charge movement in skeletal muscle: a possible step in excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1973;242:244–246. doi: 10.1038/242244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LM, McCleskey EW, Almers W. Dihydropyridine receptors in muscle are voltage-dependent but most are not functional calcium channels. Nature. 1985;314:747–751. doi: 10.1038/314747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculptoreanu A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Voltage-dependent potentiation of L-type Ca2+ channels due to phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nature. 1993;364:240–243. doi: 10.1038/364240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shainberg A, Cohen SA, Nelson PG. Induction of acetylcholine receptors in muscle cultures. Pflügers Archiv. 1976;361:255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00587290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipos I, Harasztosi C, Melzer W. L-type calcium current activation in cultured human myotubes. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1997;18:353–367. doi: 10.1023/a:1018678227138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strube C, Tourneur Y, Ojeda C. Functional expression of the L-type calcium channel in mice skeletal muscle during prenatal myogenesis. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:1282–1292. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76684-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Adams BA, Numa S, Beam KG. Repeat I of the dihydropyridine receptor is critical in determining calcium channel activation kinetics. Nature. 1991;352:800–803. doi: 10.1038/352800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Beam KG, Adams BA, Niidome T, Numa S. Regions of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor critical for excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 1990;346:567–569. doi: 10.1038/346567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Grabner M, Berjukow S, Savchenko A, Glossmann H, Hering S. Chimeric L-type Ca2+ channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes reveal role of repeats III and IV in activation gating. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:131–137. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Cribbs L, Yi J, Shirokov R, PerezReyes E, Rios E. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor from Rana catesbeiana. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:25503–25509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]