Abstract

The effects of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation and blockade on subthreshold membrane potential oscillations of inferior olivary neurones were studied in brainstem slices from 12- to 21-day-old rats.

Dizocilpine (MK-801), a non-competitive NMDA antagonist, at 1-45 μm abolished spontaneous subthreshold oscillations, without affecting membrane potential, input resistance, or the low-threshold calcium current, IT. Ketamine (100 μm), a non-competitive NMDA antagonist, and L-689,560 (20 μm), an antagonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, also abolished the oscillations, while the competitive non-NMDA antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; 20-50 μm) had no effect.

NMDA (100 μm) induced 4.1 Hz subthreshold oscillations and reversibly depolarized olivary neurones by 13.7 mV. In contrast, 10 μmα-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) and 20 μm kainic acid depolarized the membrane equivalently but did not induce oscillations.

Both NMDA-induced and spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were unaffected by 1 μm tetrodotoxin and were prevented by substituting extracellular calcium with cobalt.

Removing magnesium from the perfusate did not affect spontaneous subthreshold oscillations but did prevent NMDA-induced oscillations.

NMDA-induced oscillations were resistant to 50 μm mibefradil, an IT blocker, in contrast to spontaneous oscillations. Both oscillations were inhibited by 20 μm nifedipine, an L-type calcium channel antagonist, and 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA, a P-type calcium channel blocker. Bay K 8644 (10 μm), an L-type Ca2+ agonist, significantly enhanced the amplitude of both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

The data indicate that NMDA receptor activation induces olivary neurones to manifest high amplitude membrane potential oscillations in part mediated by L- and P- but not T-type calcium currents. Moreover, the data demonstrate that NMDA receptor currents are necessary for generation of spontaneous subthreshold oscillations in the inferior olive.

Glutamate represents the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain (Hayashi, 1952). Its actions are mediated by a number of receptor types, which are classified as metabotropic and ionotropic. While metabotropic glutamate receptors transduce ligand binding to intracellular signalling cascades and may indirectly modulate ion channel function, ionotropic receptors are glutamate-gated cation channels. N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) channels, in particular, are highly permeable to Ca2+ ions (MacDermott et al. 1986) and behave as non-linear conductors due to the presence of a Mg2+ block at hyperpolarized potentials (Nowak et al. 1984; Mayer et al. 1989). The ability of the NMDA receptor to act as a glutamate-gated Ca2+ channel has been proposed to result in concomitant electrical and biochemical effects of glutamate on neurones. Thus, the NMDA receptor has been linked to a wide range of physiological processes, including synaptic transmission and integration, synaptic plasticity, and membrane potential oscillations, as well as pathological manifestations, such as epilepsy and neuronal death (Collingridge & Watkins, 1994; Schmidt et al. 1998).

Activation of the NMDA receptor produces oscillatory activity in a wide variety of spinal and supraspinal neuronal systems (Hochman et al. 1994a,b; Kim & Chandler, 1995; Flint & Connors, 1996; Kiehn et al. 1996; Guertin & Hounsgaard, 1998; Moore et al. 1999; Prime et al. 1999; Tresch & Kiehn, 2000). It has been postulated that such oscillations may participate in the generation of physiological rhythmic neuronal output and associated behaviour (Grillner & Matsushima, 1991; Schmidt et al. 1998). Moreover, NMDA receptor-induced oscillations have been associated with the onset of convulsions (Palmer et al. 1993). Therefore, the NMDA receptor provides a powerful link between glutamatergic input and the rhythmic modulation of neuronal function and behaviour.

The inferior olive of the medulla oblongata is a highly rhythmic nucleus that plays a powerful role in the regulation of movement. Its rhythmicity is conferred by a set of ionic currents (Llinás & Yarom, 1981A,b, 1986; Benardo & Foster, 1986; Yarom & Llinás, 1987; Lampl & Yarom, 1997; Bal & McCormick, 1997) and electrical coupling (Llinás et al. 1974), and it directly influences movement due to its monosynaptic connection with Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex (Eccles et al. 1966). Olivary neurones manifest oscillations in membrane potential that are subthreshold for spiking (Llinás & Yarom, 1986; Benardo & Foster, 1986) and which are mediated by the low-threshold calcium current, IT (Lampl & Yarom, 1997). The subthreshold oscillations have been postulated to be functionally related to the coordination of movement (Welsh et al. 1995) and, in the extreme, to the manifestation of rhythmic myoclonus (Welsh et al. 1998). The role that NMDA receptor currents may play in mediating oscillatory activity in olivary neurones remains unknown.

Two recently reported observations suggest that the NMDA receptor may be involved in the generation of rhythmic activity of the inferior olive. First, dizocilpine (MK-801), a non-competitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor, blocked both the tremorigenic and amnestic effects of harmaline (Du & Harvey, 1997), actions that are mediated by effects on the inferior olive (de Montigny & Lamarre, 1973; Llinás & Volkind, 1973; Llinás & Yarom, 1986; Welsh, 1998). Second, harmaline competed with MK-801 for binding to the NMDA receptor (Du et al. 1997). These findings suggest that NMDA receptors may be central in olivary function under both physiological and pathological conditions.

To address the question of NMDA receptor involvement in olivary oscillations, we studied the effects of NMDA receptor blockade and activation on inferior olivary neurones in vitro using intracellular recordings. Our findings indicate that the NMDA receptor enhances oscillatory activity in olivary neurones. Some of the data have been published in abstract form (Placantonakis & Welsh, 1999).

METHODS

Intracellular recordings were obtained from inferior olivary neurones in brainstem slices of postnatal day (P) 12-21 Sprague-Dawley rats, using a protocol previously described (Placantonakis et al. 2000). Rat usage was in accordance with local guidelines. Briefly, rats were anaesthetized with 15-20 mg ketamine (i.p.) and decapitated. The brain was removed and the brainstem was isolated. A vibratome was used to cut 400 μm parasagittal slices in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at 4 °C. After sectioning, the slices were transferred to a chamber containing ACSF at room temperature and allowed to sit for at least 1-2 h. Individual slices were moved subsequently to a submersion recording chamber where the temperature was increased to 33-35 °C over a 10 min period. ACSF flow rates of at least 5 ml min−1 were used to perfuse the slices in the recording chamber. ACSF consisted of (mm): NaCl 126, KCl 5, NaH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 2, glucose 10 and NaHCO3 26, and was aerated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2 to a final pH of 7.4. In experiments with 30 mm KCl, the excess KCl replaced an equimolar amount of NaCl in the perfusate. ACSF reagents were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Slices remained viable for at least 20 h using this protocol.

Intracellular recordings were performed in current-clamp mode with standard borosilicate glass microelectrodes filled with 3 m potassium acetate, whose direct current (DC) resistance ranged from 60 to 100 MΩ. The bridge was frequently checked to ensure adequate series resistance compensation. Only neurones with membrane potentials negative to −50 mV, showing dendritic and somatic calcium currents, fast sodium spikes, and slow inward rectification were analysed. Recordings were amplified with an Axoclamp2B amplifier and stored on the hard drive of a personal computer with pCLAMP 6 acquisition software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) sampling at 5 or 10 kHz. Analysis of recordings was performed with pCLAMP 6, Origin (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA, USA), Datapac 2000 (Run Technologies, Laguna Hills, CA, USA) and GB-Stat (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Springs, MD, USA). Fast Fourier transforms for power spectrum analysis were obtained from 10 s recordings of oscillations. When voltage was differentiated with respect to time, the result was low-pass filtered below 500 Hz. High-threshold calcium spike threshold was defined as the membrane potential immediately preceding spike initiation at which the second derivative of potential with respect to time was 0. Input resistance measurements were obtained prior to slow inward rectification and at steady-state during hyperpolarizing current pulses (Placantonakis et al. 2000). Student's t test, the χ2 test and analysis of variance were used, with significance accepted for values of P < 0.05 (Winer, 1971). Population statistics are presented as the mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Dunnett's test was used for post hoc analysis of the significant F-statistic to allow for all comparisons against a control (Winer, 1971).

The following agents were used: N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA; RBI, Natick, MA, USA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA; RBI), kainic acid (RBI), tetrodotoxin (TTX; RBI), nifedipine (RBI), ω-agatoxin IVA (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), Bay K 8644 (RBI), dizocilpine (MK-801; RBI), ketamine (RBI), L-689,560 (Tocris Cookson, Ballwin, MO, USA), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, RBI), 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV; RBI), CoCl2.6H20 (Sigma) and CdCl2.5/2H20 (Sigma). Mibefradil (Ro 40-5967) was a gift of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd (Basel, Switzerland). When CoCl2.6H20 and CdCl2.5/2H20 were used, MgSO4 was replaced with MgCl2 to ensure solubility of the divalent cations. The cumulative divalent cation concentration was kept at 4.0-4.1 mm in all experiments. All agents were diluted at least 250-fold into ACSF from aqueous or DMSO-based stock solutions.

RESULTS

Intracellular recordings were obtained from 157 inferior olivary neurones, 88 of which showed spontaneous subthreshold oscillations of the membrane potential. The mean frequency and amplitude of the oscillations in 20 randomly selected neurones were 4.9 ± 0.3 Hz and 8.1 ± 1.1 mV, respectively, in agreement with previous observations (Placantonakis et al. 2000). The mean resting potential was −61.1 ± 0.5 mV.

Blockade of NMDA receptors annihilates spontaneous subthreshold oscillations

Du & Harvey (1997) reported that systemic MK-801 antagonized the behavioural effects of harmaline in vivo. In addition, harmaline competitively inhibited MK-801 binding to olivary membranes (Du et al. 1997). These findings raised the possibility that antagonism of the NMDA receptor would suppress oscillations of the membrane potential that are believed to drive the tremor produced by harmaline (Llinás & Yarom, 1986). MK-801 was applied to brainstem slices at concentrations ranging from 1 to 45 μm. We broadly classified four concentrations as either low (1 and 5 μm) or high (15 and 45 μm). MK-801 did not change the membrane potential of olivary neurones at either the low (control −62.4 ± 2.4 mV, MK-801 −63.0 ± 4.4 mV, n = 5) or the high (control −60.2 ± 1.2 mV, MK-801 −61.1 ± 1.3 mV, n = 19) concentration. Moreover, 15 μm MK-801 did not alter either the pre-rectification (control 44.2 ± 2.5 MΩ, MK-801 46.7 ± 4.4 MΩ, n = 6) or the steady-state (control 33.3 ± 3.2 MΩ, MK-801 37.9 ± 5.5 MΩ, n = 6) components of input resistance.

An effect that occurred in 100 % of olivary neurones tested was that MK-801, at all concentrations, abolished subthreshold oscillations (n = 17; Fig. 1A). The time required for effect was dose dependent (F3,13 = 59.14; P < 0.01; Fig. 1B). The times required to abolish oscillations were 50.3 ± 2.7 min (n = 4), 48.5 ± 3.8 min (n = 3), 14.1 ± 3.1 min (n = 6) and 6.0 ± 0.6 min (n = 4) for 1, 5, 15 and 45 μm MK-801, respectively. The suppression of oscillations by MK-801 was irreversible in 13 of 17 neurones, while in four cases (1 each with 5 and 15 μm MK-801, and 2 with 45 μm MK-801) oscillations returned 10-20 min after removal of MK-801 from the perfusate. The abolition of oscillations by 15 μm MK-801 also occurred in the presence of 1 μm TTX (n = 3; data not shown), indicating that sodium currents were not required for the phenomenon.

Figure 1. MK-801 suppresses spontaneous oscillations without affecting IT.

A, recordings from a representative olivary neurone showing that 1 μm MK-801 suppresses spontaneous subthreshold oscillations without significantly changing membrane potential. B, cumulative statistics on the effects of MK-801 concentration (1, 5, 15 and 45 μm) on the time required for abolition of oscillations (□) and percentage of cells whose oscillations were abolished by MK-801 (♦). MK-801, at all doses, was successful in 100 % of the experiments at annihilating the oscillations. C, 15 μm MK-801 did not affect the low-threshold Ca2+ spike (open arrow) triggered by IT. D, the amplitude and slope of the low-threshold calcium spike were not altered by 15 μm MK-801.

As is well accepted, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations require the low-threshold calcium current IT (Lampl & Yarom, 1997). We tested whether the MK-801-mediated suppression of oscillations was due to inhibition of IT. Low-threshold calcium spikes were elicited with depolarizing current pulses from holding potentials ranging from −90 to −54 mV before and during 15 μm MK-801 treatment in five olivary neurones (Fig. 1C). Repeated-measures analysis of variance indicated that MK-801 did not significantly alter either the amplitude (control 8.6 ± 1.0 mV, MK-801 8.2 ± 1.9 mV; F1,12 = 0.50) or the slope (control 1.9 ± 0.2 mV ms−1, MK-801 1.9 ± 0.2 mV ms−1; F1,11 = 0.01) of the low-threshold calcium spike (Fig. 1D). This finding demonstrated that suppression of spontaneous subthreshold oscillations by MK-801 was not mediated by inhibition of IT.

To test whether MK-801 acted on NMDA receptors and that the effect was not due to spurious interactions of MK-801 with other targets, we tested the effects of 100 μm ketamine, a non-competitive NMDA receptor blocker (Lodge et al. 1994), and 20 μm L-689,560, an antagonist at the strychnine-insensitive glycine site of the NMDA receptor (Lodge et al. 1994). Like MK-801, neither ketamine nor L-689,560 changed the membrane potential of olivary neurones (from −62.0 ± 3.5 to −59.5 ± 4.8 mV, n = 4; and from −55.0 to −58.0 mV, n = 2, respectively). However, also like MK-801, ketamine (n = 6, 3 with 1 μm TTX; Fig. 2A) and L-689,560 (n = 3, 1 with 1 μm TTX; Fig. 2B) abolished subthreshold oscillations, supporting the conclusion that MK-801 acted on NMDA receptors to suppress the oscillations. Paradoxically, treatment of olivary neurones with 50-100 μm APV, a competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, for up to 1 h did not abolish subthreshold oscillations (n = 4; Fig. 2C). APV had no significant effect on either the membrane potential (control −65.3 ± 3.4 mV, APV −64.3 ± 3.0 mV, n = 4) or the frequency (control 4.8 ± 0.8 Hz, APV 4.5 ± 0.7 Hz, n = 4) and amplitude (control 6.3 ± 1.3 mV, APV 6.5 ± 1.3 mV, n = 4) of subthreshold oscillations.

Figure 2. NMDA but not AMPA or kainate receptors are required for spontaneous oscillations.

A, treatment of olivary neurones with 100 μm ketamine, a non-competitive antagonist at NMDA receptors, annihilated spontaneous oscillations. B, application of 20 μm L-689,560, an antagonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, also abolished spontaneous oscillations. C, in contrast, 50-100 μm APV, a competitive NMDA antagonist, failed to suppress oscillations. D, spontaneous oscillations were not affected by 20-50 μm CNQX, a competitive non-NMDA receptor antagonist.

To determine whether non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptors were required for subthreshold oscillations, we treated olivary neurones with 20-50 μm CNQX, a competitive antagonist at AMPA and kainate receptors, for up to 1 h (n = 5; Fig. 2D). CNQX did not change the membrane potential of olivary neurones (control −62.7 ± 2.1 mV, CNQX −62.3 ± 1.7 mV, n = 12) and did not suppress subthreshold oscillations. Both the frequency (control 4.8 ± 0.8 Hz, CNQX 4.7 ± 0.6 Hz, n = 5) and the amplitude (control 9.4 ± 3.2 mV, CNQX 9.7 ± 3.2 mV, n = 5) of the oscillations were unchanged by CNQX. This result indicated that NMDA, but not non-NMDA, receptors were critical for spontaneous subthreshold oscillations.

NMDA depolarizes olivary neurones and induces subthreshold oscillations

The effects of NMDA receptor activation were studied in neurones with quiescent membrane potential, as well as in neurones spontaneously manifesting subthreshold oscillations. The two electrophysiological effects of NMDA on olivary neurones are shown in Fig. 3A. Application of 100 μm NMDA for 3 min depolarized olivary neurones by 13.7 ± 1.2 mV (from −61.1 ± 1.0 to −47.4 ± 1.1 mV, n = 36; P < 0.01). In addition, NMDA induced subthreshold oscillations of membrane potential whose frequency and amplitude were 4.1 ± 0.2 Hz (n = 40) and 10.2 ± 0.9 mV (n = 34), respectively. These two effects reversed when NMDA was removed from the perfusate. Moreover, the two effects could be induced repeatedly in the same neurone within an interval as short as 15 min (n = 3). Both the depolarization and the oscillations induced by NMDA were prevented by pre-incubating the slices with 45 μm MK-801 (n = 3). The oscillations induced by NMDA were not simply a consequence of the depolarization of recorded neurones, because restoring the pre-NMDA membrane potential with direct current (DC) bias did not annihilate the oscillations (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the frequency of the NMDA-induced oscillations was not altered with DC bias, a phenomenon reminiscent of spontaneous olivary subthreshold oscillations (Llinás & Yarom, 1986; Benardo & Foster, 1986) and of oscillations in other neuronal networks (Tresch & Kiehn, 2000).

Figure 3. NMDA depolarizes the membrane and induces subthreshold oscillations.

A, recording from an olivary neurone showing the depolarization and induction of oscillations by 100 μm NMDA. The oscillations persisted when membrane potential was returned to the control value with DC bias and were reversed by removing NMDA from the bath. B, cumulative statistics on the effects of NMDA concentration (10, 25, 50 and 100 μm) on membrane depolarization (□) and percentage of cells with oscillations in the presence of NMDA (♦).

To test whether the effects of NMDA were dose dependent, we treated olivary neurones with NMDA at 10, 25 and 50 μm (Fig. 3B). NMDA at 10 μm depolarized neurones by 2.5 ± 0.3 mV (from −60.8 ± 1.3 to −58.3 ± 1.5 mV, n = 4; P < 0.05), but did not induce oscillations. NMDA at 25 μm depolarized neurones by 8.8 ± 1.4 mV (from −59.3 ± 1.9 to −50.5 ± 2.9 mV, n = 4; P < 0.05) and induced oscillations whose frequency and amplitude were 2.1 ± 0.5 Hz and 12.1 ± 0.9 mV, respectively, in 50 % of neurones. Application of 50 μm NMDA depolarized olivary neurones by 11.0 ± 1.6 mV (control −62.3 ± 1.8 mV, NMDA −51.3 ± 3.0 mV, n = 3; P < 0.05) and induced oscillations with a frequency of 2.3 ± 0.4 Hz and an amplitude of 14.3 ± 3.2 mV in 100 % of cells tested. Completely randomized analysis of variance indicated a significant effect of NMDA concentration on membrane depolarization (F3,43 = 3.99; P < 0.05).

The frequency and amplitude of NMDA-induced subthreshold oscillations were significantly different from spontaneous oscillations. Figure 4A shows a typical example in which 100 μm NMDA depolarized the membrane and reversibly changed the characteristics of the oscillation. Superposition of spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations indicated that the latter were about 3 Hz slower, an effect that was confirmed quantitatively with power spectrum analysis (Fig. 4B). A population analysis was performed of all the neurones studied in this manner (n = 15), in which the modal oscillation frequency was determined by power spectrum analysis before and during NMDA (Fig. 4C-E). NMDA decreased the oscillation frequency in 9 of the 15 neurones by 35.3 ± 8.5 %, increased the oscillation frequency in five neurones, and had no effect on one neurone (Fig. 4C). To determine statistical significance, we plotted the distribution of frequencies before and after NMDA in a cumulative probability histogram (Fig. 4D) and analysed the two distributions with a χ2 test. The distribution of frequencies for the two oscillatory states was significantly different (P < 0.05), indicating that NMDA shifted the curve leftward, toward slower frequencies. Additionally, the amplitude of oscillations in the presence of NMDA was significantly larger than under control conditions (11.7 ± 1.3 vs. 8.0 ± 1.2 mV, n = 13; P < 0.01; Fig. 4E). The slowing of oscillation frequency and enhancement of oscillation amplitude by NMDA indicated that NMDA induced a distinctly different oscillatory state than occurred spontaneously, most certainly generated by a different mechanism of rhythmogenesis.

Figure 4. NMDA-induced oscillations differ from spontaneous oscillations in their frequency and amplitude.

A, NMDA at 100 μm depolarized the membrane and appeared to slow the oscillation frequency reversibly. B, superposition of spontaneous (continuous line) and NMDA-induced (dotted line) oscillations from the same neurone indicated that NMDA-induced oscillations had lower frequency and larger amplitude (left). Power spectrum analysis confirmed that the two oscillatory states were of different frequency (right). The power spectral data were normalized to the peak coefficient of the NMDA spectrum. C, plot of the oscillation frequency of 15 neurones before and during NMDA application. D, cumulative probability distribution of peak spectral power for the 15 neurones during spontaneous (continuous line) and NMDA-induced oscillations (dotted line). E, the amplitude of NMDA-induced oscillations was larger than the amplitude of spontaneous oscillations. *P < 0.05.

The ability of NMDA to induce subthreshold oscillations raised the possibility that the effect was due to the associated depolarization. To test that hypothesis, we globally depolarized brainstem slices with ACSF containing 30 mm KCl. Even though this treatment robustly depolarized the membrane to levels comparable to and even exceeding those achieved with NMDA, oscillations were not induced (n = 3). This finding reinforced the view that depolarization did not suffice for induction of oscillations.

To test whether the induction of oscillation was a unique property of NMDA receptors and not a global property of ionotropic glutamate receptors, we treated slices with 10 μm AMPA and 20 μm kainic acid (Fig. 5). AMPA depolarized neurones by 14.9 ± 3.0 mV (from −60.6 ± 2.3 to −45.7 ± 2.7 mV, n = 7; P < 0.05), while kainic acid depolarized by 17.5 ± 5.8 mV (from −63.9 ± 2.6 to −46.3 ± 5.7 mV, n = 7; P < 0.05). However, neither AMPA nor kainic acid induced oscillations, indicating that induction of oscillations at depolarized potentials was unique and specific to activation of the NMDA receptor.

Figure 5. AMPA and kainic acid do not induce oscillations.

A, application of 100 μm NMDA depolarized the membrane and induced subthreshold oscillations. Same neurone as in Fig. 2A. B, application of 10 μm AMPA significantly depolarized the membrane but did not induce oscillations. C, treatment with 20 μm kainic acid also depolarized the membrane without inducing oscillations.

Basic properties of spontaneous and NMDA-induced subthreshold oscillations

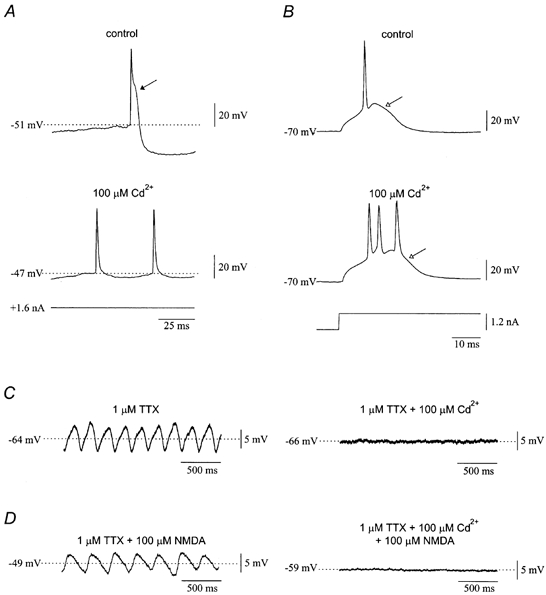

Spontaneous subthreshold oscillations in the inferior olive are insensitive to TTX and dependent on Ca2+ (Llinás & Yarom, 1986; Benardo & Foster, 1986). To test whether the depolarization and induction of oscillations with NMDA required sodium conductances, we applied NMDA in the presence of 1 μm TTX (Fig. 6A). TTX by itself had no effect on the resting membrane potential (control −60.0 ± 1.7 mV, TTX −60.5 ± 1.8 mV, n = 8 representative neurones). Moreover, TTX altered neither the pre-rectification (control 49.3 ± 4.0 MΩ, TTX 43.5 ± 8.3 MΩ) nor the steady-state (control 33.7 ± 3.1 MΩ, TTX 29.9 ± 8.8 MΩ) components of input resistance in five representative neurones. Both the frequency (control 5.2 ± 0.6 Hz, TTX 4.4 ± 0.7 Hz) and the amplitude (control 8.7 ± 1.8 mV, TTX 8.6 ± 2.0 mV, n = 7 representative neurones) of spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were not affected by TTX (Table 1). Application of 100 μm NMDA in the presence of TTX depolarized the membrane by 13.4 ± 1.6 mV (from −60.2 ± 1.3 to −46.8 ± 1.7 mV, n = 21; P < 0.05), a value not different from the depolarization produced by NMDA in the absence of TTX (14.1 ± 1.9 mV, n = 15). Moreover, TTX did not prevent NMDA from inducing subthreshold oscillations, which had a frequency of 4.4 ± 0.3 Hz (n = 23) and an amplitude of 10.0 ± 1.3 mV (n = 18; Table 1). These values were not different from the values for oscillations induced by NMDA in the absence of TTX, which had a frequency of 3.6 ± 0.4 Hz (n = 17) and an amplitude of 10.5 ± 1.3 mV (n = 16). The findings suggested that TTX-sensitive sodium conductances were not required for the depolarization or induction of oscillations by NMDA and that NMDA produced its effects by acting directly on olivary neurones.

Figure 6. Basic properties of NMDA-induced oscillations.

A, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were not affected by the presence of 1 μm TTX. Subsequent application of 100 μm NMDA significantly depolarized the membrane and induced oscillations with frequency and amplitude indistinguishable from those obtained with NMDA alone. B, when Ca2+ was removed from the perfusate and replaced with an equimolar amount of Co2+, spontaneous oscillations were abolished and 100 μm NMDA subsequently failed to depolarize the membrane and induce oscillations.

Table 1.

Comparison of spontaneous and NMDA-induced olivary subthreshold oscillations

| Spontaneous | NMDA-induced | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Frequency (Hz) | Amplitude (mV) | Frequency (Hz) | Amplitude (mV) | |

| TTX (1 μm) | Pre | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 8.7 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 0.4 (17) | 10.5 ± 1.3 (16) |

| Post | 4.4 ± 0.7 (7) | 8.6 ± 2.0 (7) | 4.4 ± 0.3 (23)† | 10.0 ± 1.3 (18)† | |

| 0 Ca2+, 2 mm Co2+ | Pre | Annihilated oscillations (4) | Annihilated oscillations (4) | ||

| Post | |||||

| 0 Mg2+, 4 mm Ca2+ | Pre | 5.1 ± 1.3 | 8.1 ± 1.5 | Prevented oscillations (5) | |

| Post | 6.8 ± 0.9 (4) | 11.1 ± 3.0 (4) | |||

| Mibefradil (50 μm) | Pre | Annihilated oscillations (6) | 4.1 ± 0.2 (40) | 10.2 ± 0.9 (34) | |

| Post | 3.1 ± 0.5 (4)† | 10.2 ± 1.4 (4)† | |||

| Cd2+ (100 μm) | Pre | Annihilated oscillations (4) | Annihilated oscillations (6) | ||

| Post | |||||

| Nifedipine (20 μm) | Pre | Annihilated oscillations (6) | 4.1 ± 0.2 (40) | 10.2 ± 0.9 (34) | |

| Post | 3.8 ± 1.2 (6 of 7)† | 2.4 ± 1.0 (6 of 7)*† | |||

| Bay K 8644 (10 μm) | Pre | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 2.3 |

| Post | 3.5 ± 0.2 (3) | 6.6 ± 0.6 (3)* | 3.9 ± 0.2 (6) | 12.6 ± 2.4 (6)* | |

| ω-Agatoxin IVA (200 nm) | Pre | 4.9 ± 0.3 (20) | 8.1 ± 1.1 (20) | 4.1 ± 0.2 (40) | 10.2 ± 0.9 (34) |

| Post | 4.0 (2) | 1.7 (2) | 2.9 ± 0.8 (6 of 8)*† | 1.8 ± 0.4 (6 of 8)*† | |

P < 0.05, compared to Pre.

Unpaired comparison between Pre and Post. Numbers in parentheses are the numbers of neurones studied.

To test whether Ca2+ ions were critical for the effects of NMDA, we replaced Ca2+ with an equimolar amount of Co2+ in the perfusate (Fig. 6B; Table 1). Substitution of Co2+ for Ca2+ did not significantly change the membrane potential of olivary neurones (control −59.3 ± 2.9 mV, Co2+ −61.8 ± 2.9 mV, n = 4). Moreover, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were abolished under such conditions (n = 4). When 100 μm NMDA was applied to olivary neurones maintained in 0 Ca2+, 2 mm Co2+ ACSF, the membrane did not depolarize (control −61.5 ± 3.0 mV, Co2++ NMDA −60.3 ± 2.9 mV, n = 4) and oscillations were not induced (n = 4; Fig. 6B). This finding demonstrated that Ca2+ ions were required for both the depolarization and the generation of NMDA-induced oscillations.

The Mg2+ block regulates NMDA-induced but not spontaneous oscillations

Mg2+ confers voltage dependence upon the NMDA receptor current, because Mg2+ blocks the pore of NMDA receptor-associated channel at rest and the inhibition is removed by depolarization (Nowak et al. 1984). The voltage dependence of the NMDA receptor current has been shown to be required for induction of oscillatory states by NMDA in other neuronal systems, such as trigeminal motorneurones (Kim & Chandler, 1995). To test whether the voltage dependence of the NMDA receptor current was required for spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations, Mg2+ was removed from the perfusate and replaced with an equimolar amount of Ca2+ (Table 1). In 0 Mg2+, 4 mm Ca2+ ACSF, there was no significant change in the membrane potential of olivary neurones (control −56.8 ± 3.4 mV, 0 Mg2+ −58.5 ± 3.3 mV, n = 4). The properties of spontaneous oscillations did not change after removal of Mg2+. Thus, their frequency (control 5.1 ± 1.3 Hz, 0 Mg2+ 6.8 ± 0.9 Hz, n = 4) and amplitude (control 8.1 ± 1.5 mV, 0 Mg2+ 11.1 ± 3.0 mV, n = 4; Fig. 7A) remained unaffected.

Figure 7. Mg2+ is required for NMDA-induced but not spontaneous oscillations.

A, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were not affected by removing Mg2+ from the perfusate. B, removing Mg2+ from the perfusate did not impair the ability of 100 μm NMDA to depolarize the neurone but did prevent the induction of oscillations. The effects of NMDA in normal ACSF are shown on the left for comparison. C, application of 100 μm NMDA in ACSF containing 0 Mg2+ and 4 mm Ca2+ completely and irreversibly depolarized the neurone.

In the absence of Mg2+, 100 μm NMDA robustly depolarized olivary neurones without inducing oscillations (n = 5; Fig. 7B). In fact, the depolarization in the absence of Mg2+ was so extreme that the neurones never recovered (Fig. 7C), suggesting that activation of NMDA receptors can be excitotoxic under such conditions. The results showed that the Mg2+-mediated voltage dependence of the NMDA receptor current was required for NMDA-induced but not spontaneous oscillations.

IT is required for spontaneous but not NMDA-induced oscillations

Spontaneous subthreshold oscillations in the inferior olive depend upon voltage-gated calcium currents, in particular the low-threshold calcium current IT (Lampl & Yarom, 1997). We tested whether the subthreshold oscillations induced by NMDA also depended on voltage-gated calcium currents.

First, we examined whether IT was involved in NMDA-induced oscillations by applying 50 μm mibefradil (Table 1), a specific blocker of IT (McDonough & Bean, 1998). Mibefradil did not significantly change the resting membrane potential of olivary neurones (control −60.7 ± 1.7 mV, mibefradil −60.0 ± 2.1 mV, n = 9) or antagonize high-threshold calcium currents (n = 3; filled arrows in Fig. 8A), which generate the after-depolarization accompanying the fast sodium spike triggered from depolarized holding potentials (Llinás & Yarom, 1981a,b). Mibefradil significantly reduced IT(n = 6, 4 with 1 μm TTX; Fig. 8B), as evidenced by a significant decrease of the amplitude (from 14.4 ± 1.8 to 8.8 ± 1.9 mV; F1,13= 9.98, P < 0.01) and the slope (from 2.0 ± 0.5 to 0.7 ± 0.3 mV ms−1; F1,11 = 6.85, P < 0.05) of the low-threshold calcium spike elicited with depolarizing current pulses from holding potentials ranging from −75 to −57 mV (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. IT is not required for NMDA-induced oscillations.

A, application of 50 μm mibefradil did not affect the after-depolarization (filled arrow) produced by high-threshold Ca2+ currents. B, the low-threshold Ca2+ spike (open arrow) produced by IT was abolished by 50 μm mibefradil. Same neurone as in A. C, mibefradil significantly reduced the amplitude and the slope of the low-threshold calcium spike. *P < 0.05. D, mibefradil (50 μm) abolished spontaneous subthreshold oscillations, but subsequent application of 100 μm NMDA induced oscillations with frequency and amplitude indistinguishable from those induced by NMDA alone.

Mibefradil at 50 μm abolished spontaneous subthreshold oscillations in the presence of TTX, indicating their dependence on IT(n = 6; Fig. 8D). Subsequent application of 100 μm NMDA in the presence of mibefradil depolarized olivary neurones by 17.3 ± 4.1 mV (control −60.3 ± 2.2 mV, mibefradil + NMDA −43.0 ± 4.5 mV, n = 4) and induced subthreshold oscillations in 100 % of the neurones (Fig. 8D). The mean frequency and amplitude of the NMDA-induced oscillations in the presence of mibefradil were 3.2 ± 0.3 Hz and 10.2 ± 1.4 mV, respectively (n = 4). Both the depolarization and the properties of the oscillations were not different from those obtained with NMDA in the absence of mibefradil. The frequency of the NMDA-induced oscillations in the four neurones was significantly different from the frequency of spontaneous oscillations (4.0 ± 0.4 Hz; P < 0.05) prior to treatment with mibefradil, again indicating different rhythmogenesis between the two oscillatory states. The results indicated that, although IT is required for spontaneous oscillations, it is not necessary for NMDA-induced oscillations.

Contributions of high-threshold calcium currents to both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations

The fact that NMDA-induced oscillations were initiated at depolarized potentials raised the possibility that high-threshold calcium currents participated in the phenomenon. Cd2+ at low concentrations is known to selectively block high-threshold calcium currents while leaving IT intact (Pedroarena & Llinás, 1997). Moreover, Cd2+ at low concentrations does not block NMDA receptor currents (Halabisky et al. 2000), although evidence for such antagonism exists in reduced preparations (Mayer et al. 1989). When olivary neurones were treated with 100 μm Cd2+, there was a relatively small but significant hyperpolarization of 3.1 ± 0.8 mV (from −60.2 ± 1.5 to −63.3 ± 2.1 mV, n = 9; P < 0.05). Cd2+ abolished the after-depolarization generated by high-threshold calcium currents and the ensuing calcium-dependent after-hyperpolarization (n = 3; Fig. 9A). In contrast, the low-threshold calcium spike elicited from hyperpolarized holding potentials was unaffected by Cd2+(n = 3; Fig. 9B), indicating that Cd2+ had no effect on IT.

Figure 9. Cd2+ abolishes spontaneous oscillations and prevents induction of oscillations by NMDA.

A, the after-depolarization (filled arrow) generated by high-threshold calcium currents and the calcium-dependent after-hyperpolarization were blocked by 100 μm Cd2+. B, in contrast, Cd2+ had no effect on the low-threshold Ca2+ spike (open arrow). Same cell as in A. C, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were abolished by 100 μm Cd2+ in the presence of 1 μm TTX. D, when 100 μm NMDA was given to olivary neurones in the presence of 100 μm Cd2+ and 1 μm TTX, the associated depolarization was reduced and the oscillations were completely prevented. The effects of NMDA in normal ACSF are shown on the left for comparison.

Application of 100 μm Cd2+ to olivary neurones manifesting spontaneous subthreshold oscillations in the presence of 1 μm TTX abolished the oscillations (n = 4; Fig. 9C; Table 1). When 100 μm NMDA was applied to olivary neurones in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 100 μm Cd2+, there was a significant depolarization of 4.8 ± 1.3 mV (from −61.3 ± 2.3 to −56.5 ± 3.2 mV, n = 6; P < 0.05), which was smaller than the depolarization produced by NMDA in the absence of Cd2+ (P < 0.05). More importantly, NMDA failed to induce subthreshold oscillations in the presence of Cd2+(n = 6; Fig. 9D; Table 1). The finding suggested that high-threshold calcium currents may be involved in the generation of both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

L-type and P-type calcium currents amplify both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations

Induction of oscillations by NMDA in other neuronal types is known to depend on activation of L-type calcium currents (Guertin & Hounsgaard, 1998). Moreover, there exists evidence suggesting interaction between the NMDA receptor and L-type currents in other neuronal functions, such as epileptogenesis (Palmer et al. 1993) and synaptic regulation of protein phosphorylation and gene expression (Rajadhyaksha et al. 1999). We tested whether L-type currents were involved in spontaneous and NMDA-induced olivary oscillations by using 20 μm nifedipine (Table 1). In the presence of 1 μm TTX, nifedipine did not significantly change resting membrane potential (control −60.5 ± 1.8 mV, nifedipine −60.3 ± 1.9 mV, n = 10). In addition, nifedipine did not alter either the pre-rectification (control 43.5 ± 8.3 MΩ, nifedipine 48.4 ± 5.3 MΩ; n = 5) or the steady-state (control 29.9 ± 8.8 MΩ, nifedipine 31.9 ± 5.8 MΩ, n = 5) components of input resistance (Fig. 10A). High-threshold calcium spike parameters in the presence of TTX were measured before and during application of nifedipine (Fig. 10B). The following observations were made regarding the actions of nifedipine in five neurones (Fig. 10C): (a) spike threshold remained unchanged (control −31.5 ± 2.3 mV, nifedipine −34.2 ± 1.6 mV); (b) the peak of the spike decreased from 9.7 ± 3.4 to 2.3 ± 2.7 mV (P < 0.05); (c) spike amplitude (Vpeak − Vthreshold) decreased from 41.2 ± 2.2 to 36.5 ± 1.7 mV (P < 0.05); and (d) spike slope decreased from 18.3 ± 2.0 to 11.9 ± 0.8 mV ms−1 (P < 0.05). In contrast, the low-threshold calcium spike was not altered by nifedipine (n = 5; Fig. 10A).

Figure 10. L-type Ca2+ currents amplify both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

A, application of 20 μm nifedipine in the presence of 1 μm TTX did not affect input resistance or the low-threshold Ca2+ spike (open arrow). B, the high-threshold Ca2+ spike, on the contrary, was reduced by nifedipine. C, comparison of high-threshold Ca2+ spike parameters before and in the presence of nifedipine revealed that the spike peak, amplitude and slope were significantly decreased by nifedipine. *P < 0.05. D, nifedipine abolished spontaneous subthreshold oscillations in the presence of 1 μm TTX. E, application of 100 μm NMDA in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 20 μm nifedipine resulted in a robust depolarization but diminished oscillations.

In the presence of 1 μm TTX and 20 μm nifedipine, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations were abolished (n = 6; Fig. 10D). When 100 μm NMDA was applied in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 20 μm nifedipine, the membrane was significantly depolarized by 15.0 ± 3.1 mV (from −60.7 ± 2.5 to −45.7 ± 2.4 mV, n = 7; P < 0.05), a magnitude not statistically different from the one obtained with NMDA alone. Moreover, in 6 of 7 cells tested, nifedipine significantly attenuated the amplitude of NMDA oscillations (2.4 ± 1.0 mV; P < 0.05), often to a level at which the oscillations were barely discernible, without changing their frequency (3.8 ± 1.2 Hz) (Fig. 10E). These findings suggested that L-type calcium channels amplified both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

To confirm independently that L-type currents contributed to spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations, we applied 10 μm Bay K 8644 (Table 1), an agonist at L-type calcium channels (Takeda et al. 1995). Bay K 8644 by itself did not affect resting potential (control −59.8 ± 1.1 mV, Bay K 8644 −59.7 ± 2.4 mV, n = 6). In the presence of 1 μm TTX and 10 μm Bay K 8644, the amplitude of spontaneous subthreshold oscillations increased from 3.3 ± 0.2 to 6.6 ± 0.6 mV (n = 3; P < 0.05), although their frequency was unchanged (control 3.3 ± 0.1 Hz, Bay K 8644 3.5 ± 0.2 Hz, n = 3; Fig. 11A). When 100 μm NMDA was applied in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 10 μm Bay K 8644 (n = 6; Fig. 11B), the depolarization (14.8 ± 3.1 mV) did not differ from the depolarization achieved with NMDA alone (17.3 ± 2.4 mV). However, Bay K 8644 significantly enhanced the amplitude of the oscillations produced by NMDA (from 8.5 ± 2.3 to 12.6 ± 2.4 mV, n = 6; P < 0.05), without changing oscillation frequency (control 4.3 ± 0.4 Hz, Bay K 8644 3.9 ± 0.2 Hz, n = 6; Fig. 11B). The findings further indicated that L-type channels contribute to both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

Figure 11. Bay K 8644 enhances the amplitude of spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

A, application of 10 μm Bay K 8644 in the presence of 1 μm TTX enhanced the amplitude of spontaneous subthreshold oscillations. B, when 100 μm NMDA was given to olivary neurones in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 10 μm Bay K 8644, the amplitude of the oscillations increased significantly. The recordings are from the same neurone.

It has been reported that olivary neurones have P-type calcium channels (Hillman et al. 1991; Manfridi et al. 1993). To test the contribution of P-type currents to NMDA-induced oscillations, we incubated slices in ACSF containing 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA for at least 1 h (Table 1). Olivary neurones treated with ω-agatoxin IVA had a resting potential of −60.9 ± 3.1 mV (n = 7). We compared the parameters of high-threshold calcium spikes elicited in the presence of TTX and ω-agatoxin IVA in three neurones and compared them to a population of eight neurones treated with 1 μm TTX alone (Fig. 12A). We found the following effects of ω-agatoxin IVA (Fig. 12B): (a) spike threshold did not change (control −31.7 ± 2.2 mV, ω-agatoxin IVA −29.4 ± 4.7 mV); (b) the peak of the spike was not affected (control 8.8 ± 2.2 mV, ω-agatoxin IVA −1.0 ± 6.5 mV); (c) spike amplitude (Vpeak − Vthreshold) decreased from 40.6 ± 1.8 to 29.3 ± 0.9 mV (P < 0.05); and (d) spike slope decreased from 17.9 ± 1.5 to 9.1 ± 1.6 mV ms−1 (P < 0.05).

Figure 12. P-type Ca2+ currents contribute to spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

A, high-threshold Ca2+ spikes elicited in the presence of 1 μm TTX were attenuated by 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA. The recordings are from 2 different neurones and were superimposed to facilitate comparison. B, statistical analysis showed that high-threshold Ca2+ spike amplitude and slope were reduced by ω-agatoxin IVA. *P < 0.05. C, in 2 neurones spontaneously manifesting subthreshold oscillations, 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA appeared to reduce the amplitude of the oscillations. D, application of 100 μm NMDA to a neurone in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA depolarized the membrane but failed to produce oscillations.

In the presence of 1 μm TTX and 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations appeared to have reduced amplitude (1.7 mV, n = 2), but unaltered frequency (4.0 Hz, n = 2; Fig. 12C) when compared to 20 representative neurones recorded in the absence of ω agatoxin IVA (8.1 ± 1.1 mV and 4.9 ± 0.3 Hz, respectively). When 100 μm NMDA was applied in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA (Fig. 12D), there was a depolarization of 15.6 ± 5.1 mV (from −60.8 ± 3.5 to −46.1 ± 6.0 mV, n = 7; P < 0.05), which was indistinguishable from the depolarization achieved with NMDA in the absence of ω-agatoxin IVA. In 6 of 8 trials, ω-agatoxin IVA significantly decreased both the frequency (2.9 ± 0.8 Hz; P < 0.05) and amplitude (1.8 ± 0.4 mV; P < 0.01) of NMDA-induced oscillations when compared to the values obtained with NMDA in the absence of ω-agatoxin IVA. In two cases, NMDA induced 3.3 and 2.1 Hz oscillations of robust amplitude (19.1 and 18.9 mV, respectively) in two ω-agatoxin IVA-treated neurones. However, NMDA had been previously applied to the same neurones. Therefore, the lack of effect of ω agatoxin IVA may represent depolarization-dependent removal of inhibition by ω-agatoxin IVA (Mintz et al. 1992). In summary, these findings suggested that P-type calcium channels were involved in the amplification of both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations.

DISCUSSION

The experiments demonstrate that the NMDA receptor plays an important, if not essential, role in the oscillatory activity of inferior olivary neurones. On the basis of two general findings, the experiments provide the novel insight that there are two uniquely different oscillatory states in olivary neurones, determined by the degree of activation of the NMDA receptor. First, spontaneous subthreshold oscillations manifested at normal resting potential are consistently abolished upon blockade of NMDA receptors with MK-801 or ketamine. Antagonism of non-NMDA receptors does not affect the oscillations, suggesting that this is a unique property of the NMDA receptor. Second, activation of NMDA receptors invariably generates subthreshold oscillations at depolarized potentials regardless of whether olivary neurones have quiescent or spontaneously oscillating membrane potential initially. The effect is also unique to the NMDA receptor, because activation of AMPA and kainate receptors does not produce oscillations, despite an equally robust depolarization. As compared to spontaneous subthreshold oscillations, NMDA-induced oscillations are much more likely to trigger rhythmic trains of action potentials because they are significantly larger than spontaneous oscillations and because NMDA depolarizes the membrane and brings it closer to spike threshold.

The two oscillatory states are similar in some respects but different in others. The frequency of both spontaneous and NMDA-induced olivary oscillations is not altered with DC bias. This property suggests an ensemble origin for both oscillations, probably underlain by gap junctions (Llinás & Yarom, 1986; Tresch & Kiehn, 2000). Also, both types of oscillations are calcium dependent and do not require sodium conductances. In contrast, the non-linearity conferred upon the NMDA receptor current by the voltage-dependent Mg2+ block is required for NMDA oscillations, in accordance with previous findings in other neuronal types (Kim & Chandler, 1995), but is not required for spontaneous oscillations. Therefore, the role of the NMDA receptor in the two oscillatory states is different. At depolarized potentials and upon activation, the NMDA receptor produces an oscillating current, whereas at resting potential the receptor may allow a background level of current that is permissive for spontaneous oscillations but is insignificant, by itself, for large effects on membrane potential. A permissive role of the NMDA receptor in spontaneous oscillations is consistent with its well-recognized involvement in biochemical signalling pathways, whose effects within the inferior olive remain to be investigated.

Spontaneous and NMDA-induced subthreshold oscillations rely on different sets of calcium currents. Spontaneous oscillations have been shown to require the Ni2+-sensitive, low-threshold calcium current, IT (Lampl & Yarom, 1997), a result that was reproduced in this study with mibefradil, a specific blocker of IT. The localization of this current is presumed to be predominantly somatic in olivary neurones (Llinás & Yarom, 1981a,b). NMDA-induced oscillations, on the contrary, are completely insensitive to mibefradil, which suggests that NMDA shifts the site of rhythmogenesis from the soma to the dendrites. Indeed, the decrease in oscillation frequency by NMDA is consistent with a shift in dominance from the soma to the dendrites, whose involvement is believed to predispose toward lower frequency oscillations (Llinás & Yarom, 1986).

Both spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations depend on L-type and P-type high-threshold calcium currents. The L-type current in inferior olivary neurones appears to have a high threshold for activation, as demonstrated by the lack of effect of nifedipine on the threshold of the high-threshold calcium spike, but significant effect on its peak. The P-type current appears to have an intermediate threshold for activation, as evidenced by the lack of effect of ω-agatoxin on threshold and peak, but significant effect on spike amplitude. These findings agree with the properties of the high-threshold calcium channels (Moreno Davila, 1999) and imply that there is at least one additional high-threshold calcium current that initiates the high-threshold calcium spike in olivary neurones.

The functional association between NMDA receptors and L-type channels appears to be a common property of the mammalian nervous system. Such functional coupling has been previously reported for spinal oscillations and convulsions induced by NMDA (Palmer et al. 1993; Guertin & Hounsgaard, 1998), as well as in the case of protein phosphorylation mediated by the NMDA receptor (Rajadhyaksha et al. 1999). Thus, it is not surprising that this interaction is essential for the robustness of the membrane potential oscillations in the inferior olive induced by NMDA.

The finding that both L- and P-type channels contribute to spontaneous oscillations was unexpected and may represent an active role for these channels in compensating for electrotonic decay between gap junctions at distal dendrites and the soma where rhythmogenesis occurs spontaneously. Indeed, high-threshold calcium currents are believed to be predominantly located in dendrites of olivary neurones (Llinás & Yarom, 1981a,b). The importance of L-type currents for amplifying spontaneous and NMDA-induced oscillations was reinforced by the enhancement of the amplitude of oscillations by Bay K 8644, an agonist of L-type currents.

Harmaline is known to generate tremor due to rhythmic activation of inferior olivary neurones (de Montigny & Lamarre, 1973; Llinás & Volkind, 1973). The induction of olivary oscillations by harmaline was attributed to a direct action upon IT and hyperpolarization of the membrane (Llinás & Yarom, 1986). Du & Harvey (1997) reported that MK-801 antagonized the tremor and impairment of associative learning induced by harmaline in vivo. Moreover, Du et al. (1997) showed that harmaline antagonized MK-801 binding to rat brain. Those findings suggested that MK-801 might have acted by blocking harmaline's enhancement of IT. Our experiments confirm the anti-oscillatory properties of MK-801. However, the data indicate that MK-801 blocks spontaneous oscillation without suppressing IT and imply that the generation of olivary oscillations is more complex than previously appreciated, with multiple substrates as potential targets of suppressive agents.

The ability of MK-801 to suppress spontaneous olivary oscillations suggests that a tonic level of glutamate release in the brainstem slice supports olivary rhythmogenesis. The fact that spontaneous oscillations persist in the presence of TTX (Llinás & Yarom, 1986; Benardo & Foster, 1986) implies that release of glutamate can occur without presynaptic action potentials, as has been shown in the in vitro hippocampus (McKinney et al. 1999). If true for the inferior olive, the degree of NMDA receptor activation during spontaneous oscillations must be very small, because MK-801 did not appreciably change membrane potential or input resistance. Although it cannot be totally discounted that MK-801 may act at a target other than the NMDA receptor to suppress the oscillations, its actions were mimicked by ketamine, a non-competitive NMDA antagonist, and L-689,560, an antagonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor. Taken together, the data support the hypothesis that abolition of spontaneous oscillations by MK-801 was due to a specific antagonism of the NMDA receptor.

One area of uncertainty relates to the finding that APV failed to abolish spontaneous subthreshold oscillations. This may relate to the different modes of action of MK-801 and APV. APV is a competitive antagonist of the NMDA receptor and may be unable to effectively compete with glutamate in the olive at the concentrations employed. MK-801, on the other hand, blocks the pore of the NMDA receptor-associated ion channel irreversibly, and completely prevents current flow. Differences between MK-801 and APV in their ability to block NMDA receptor-dependent phenomena have been demonstrated (Pringle et al. 2000; Sturgess et al. 2000), suggesting different blocking efficacies between these two antagonists.

Given that the major difference between NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in terms of their ionic selectivity lies in the large Ca2+ fluxes through the former, it is possible that the NMDA receptor Ca2+ current activates biochemical cascades that permit spontaneous oscillations. In this hypothesis, the Ca2+ flux initiates a signalling rather than an electrophysiological mechanism to alter electrical coupling, given that the non-linearity of the receptor current is not required for such oscillations. The subcellular localization of NMDA receptors in the dendrites of olivary neurones may be of the utmost importance in this scheme. Dendritic spines in the olive are sites of both chemical and electrical synaptic transmission, the latter mediated by gap junctions. It is likely that Ca2+ flux through NMDA receptors may regulate gap junctional conductance via activation of Ca2+-dependent enzymes (Yang et al. 1990; Pereda et al. 1998). Thus, in the presence of NMDA receptor currents, gap junctional currents would be potentiated, while in their absence, as occurs with MK-801, gap junctional communication would be reduced to levels unable to support ensemble subthreshold oscillations.

It is believed that brain ischaemia can generate hyperglutamatergic states, in which glutamate release from presynaptic terminals is excessive. Such states can result in neuronal death, which is partly preventable by blockade of NMDA receptors (Simon et al. 1984; Ozyurt et al. 1988), suggesting that these receptors are essential to the excitotoxic effects of glutamate. The inferior olive may respond to ischaemia with uncontrolled rhythmic output resulting from NMDA-induced subthreshold oscillations. This excessive output could in turn kill the synaptic targets of olivary neurones via transneuronal excitotoxicity (O'Hearn & Molliver, 1997). Indeed, global ischaemia in the rat induces defined patterns of Purkinje cell death, which are preventable by disrupting the olivocerebellar projection (Welsh et al. 2000). Our findings provide a working hypothesis for the mechanism underlying ischaemia-induced Purkinje cell death. In such a model, sustained and rhythmic firing of the inferior olive produced by NMDA receptor activation overexcites metabolically strained Purkinje cells, killing them.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by United States Public Health Service Grant NS31224 from the United States National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Myoclonus Research Foundation.

References

- Bal T, McCormick DA. Synchronized oscillations in the inferior olive are controlled by the hyperpolarization-activated cation current Ih. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:3145–3156. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benardo L, Foster E. Oscillatory behavior in inferior olive neurons: mechanism, modulation, cell aggregates. Brain Research Bulletin. 1986;17:773–784. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Watkins JC. The NMDA Receptor. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- DeMontigny C, Lamarre Y. Rhythmic activity induced by harmaline in the olivo-cerebellar-bulbar system of the cat. Brain Research. 1973;53:81–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Aloyo VJ, Harvey JA. Harmaline competitively inhibits [3H]MK-801 binding to the NMDA receptor in rabbit brain. Brain Research. 1997;770:26–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Harvey JA. Harmaline-induced tremor and impairment of learning are both blocked by dizocilpine in the rabbit. Brain Research. 1997;745:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Llinás R, Sasaki K. The excitatory synaptic action of climbing fibres on the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Journal of Physiology. 1966;182:268–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AC, Connors BW. Two types of network oscillations in neocortex mediated by distinct glutamate receptor subtypes and neuronal populations. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;75:951–957. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Matsushima T. The neural network underlying locomotion in lamprey-synaptic and cellular mechanisms. Neuron. 1991;7:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90069-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin PA, Hounsgaard J. NMDA-induced intrinsic voltage oscillations depend on L-type calcium channels in spinal motorneurons of adult turtles. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:3380–3382. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabisky B, Friedman D, Radojicic M, Strowbridge BW. Calcium influx through NMDA receptors directly evokes GABA release in olfactory bulb granule cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:5124–5134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-05124.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T. A physiological study of epileptic seizures following cortical stimulation in animals and its application to human clinics. Japanese Journal of Physiology. 1952;3:46–64. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.3.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman D, Chen S, Aung TT, Cherksey B, Sugimori M, Llinás R. Localization of P-type calcium channels in the central nervous system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:7076–7080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman S, Jordan LM, MacDonald JF. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated voltage oscillations in neurons surrounding the central canal in slices of rat spinal cord. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994a;72:565–577. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman S, Jordan LM, Schmidt BJ. TTX-resistant NMDA receptor-mediated voltage oscillations in mammalian lumbar motorneurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994b;72:2559–2562. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Johnson BR, Raastad M. Plateau properties in mammalian spinal interneurons during transmitter-induced locomotor activity. Neuroscience. 1996;75:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YI, Chandler SH. NMDA-induced burst discharge in guinea pig trigeminal motorneurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:334–346. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampl I, Yarom Y. Subthreshold oscillations and resonant behavior: two manifestations of the same mechanism. Neuroscience. 1997;78:325–341. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Baker R, Sotelo C. Electrotonic coupling between neurons in cat inferior olive. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1974:560–571. doi: 10.1152/jn.1974.37.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Volkind RA. The olivo-cerebellar system: functional properties as revealed by harmaline-induced tremor. Experimental Brain Research. 1973;18:69–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00236557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Yarom Y. Electrophysiology of mammalian inferior olivary neurones in vitro. Different types of voltage-dependent ionic conductances. Journal of Physiology. 1981a;315:549–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Yarom Y. Properties and distribution of ionic conductances generating electroresponsiveness of mammalian inferior olivary neurones in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1981b;315:569–584. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Yarom Y. Oscillatory properties of guinea-pig inferior olivary neurones and their pharmacological modulation: an in vitro study. Journal of Physiology. 1986;376:163–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge D, Jones M, Fletcher E. Collingridge GL, Watkins JC. The NMDA Receptor. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. Non-competitive antagonists of N-methyl-D-aspartate; pp. 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- MacDermott AB, Mayer ML, Westbrook GL, Smith SJ, Barker JL. NMDA-receptor activation increases cytoplasmic calcium concentration in cultured spinal cord neurons. Nature. 1986;321:519–522. doi: 10.1038/321519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough SI, Bean BP. Mibefradil inhibition of T-type calcium channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:1080–1087. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RA, Capogna M, Durr R, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Miniature synaptic events maintain dendritic spines via AMPA receptor activation. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:44–49. doi: 10.1038/4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfridi A, Charpac S, Cherksey B, Sugimori M, Llinás R. FTX selectively blocks P-type calcium current in hippocampal and olivary neurons. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1993;19:1754. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Vyklicky L, Jr, Westbrook GL. Modulation of excitatory amino acid receptors by group IIB metal cations in cultured mouse hippocampal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1989;415:329–350. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Adams ME, Bean BP. P-type calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LE, Chub N, Tabak J, O'Donovan M. NMDA-induced dendritic oscillations during a soma voltage clamp of chick spinal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:8271–8280. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08271.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MorenoDavila H. Molecular and functional diversity of voltage-gated calcium channels. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;868:102–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak L, Bregestovski P, Ascher P, Herbet A, Prochiantz A. Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature. 1984;307:462–465. doi: 10.1038/307462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hearn E, Molliver ME. The olivo-cerebellar projection mediates ibogaine-induced degeneration of Purkinje cells: A model of indirect, trans-synaptic excitotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:8828–8841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozyurt E, Graham DI, Woodruff GN, McCulloch J. Protective effect of the glutamate antagonist MK-801 in focal cerebral ischemia in the cat. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1988;8:138–143. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer GC, Stagnitto ML, Ray RK, Knowles MA, Harvey R, Garske GE. Anticonvulsant properties of calcium channel blockers in mice: N-methyl-D,L-aspartate- and Bay K 8644-induced convulsions are potently blocked by the dihydropyridines. Epilepsia. 1993;34:372–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroarena C, Llinás R. Dendritic calcium conductances generate high-frequency oscillation in thalamocortical neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:724–728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda AE, Bell TD, Chang BH, Czernik AJ, Nairn AC, Soderling TR, Faber DS. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II mediates simultaneous enhancement of gap-junctional conductance and glutamatergic transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:13272–13277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placantonakis DG, Schwarz C, Welsh JP. Serotonin suppresses subthreshold and suprathreshold oscillatory activity of rat inferior olivary neurones in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:833–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placantonakis DG, Welsh JP. NMDA receptor involvement in subthreshold oscillations of the inferior olive. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1999;25:1560. [Google Scholar]

- Prime L, Pichon Y, Moore LE. N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced oscillations in whole cell clamped neurons from the isolated spinal cord of Xenopus laevis embryos. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:1069–1073. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle AK, Self J, Eshak M, Iannotti F. Reducing conditions significantly attenuate the neuroprotective efficacy of competitive, but not other NMDA receptor antagonists in vitro. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12:3833–3842. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajadhyaksha A, Barczak A, Macías W, Leveque J-C, Lewis SE, Konradi C. L-type Ca2+ channels are essential for glutamate-mediated CREB phosphorylation and c-fos gene expression in striatal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:6348–6359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt BJ, Hochman S, MacLean JN. NMDA receptor-mediated oscillatory properties: potential role in rhythm generation in the mammalian spinal cord. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;860:189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RP, Swan JH, Griffith T, Meldrum BS. Blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors may protect against ischemic damage in the brain. Science. 1984;226:850–852. doi: 10.1126/science.6093256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgess NC, Rustad A, Fonnum F, Lock EA. Neurotoxic effects of L-2-chloropropionic acid on primary cultures of rat cerebellar granule cells. Archives of Toxicology. 2000;74:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s002040050668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Tohse N, Nayaka H, Kanno M. Voltage-dependence of Ca2+ agonist effect of YC-170 on cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;116:2134–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Kiehn O. Motor coordination without action potentials in the mammalian spinal cord. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:593–599. doi: 10.1038/75768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JP. Systemic harmaline blocks associative and motor learning by the actions of the inferior olive. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;10:3307–3320. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JP, Chang B, Menaker ME, Aicher SA. Removal of the inferior olive abolishes myoclonic seizures associated with a loss of olivary serotonin. Neuroscience. 1998;82:879–897. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JP, Lang EJ, Sugihara I, Llinás R. Dynamic organization of motor control within the olivocerebellar system. Nature. 1995;374:453–457. doi: 10.1038/374453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JP, Yuen G, Vu T, Marquez R, Seiden S, Sharma S, Aicher S. Is zebrin II neuroprotective. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2000;26:1988. [Google Scholar]

- Yang X-D, Korn H, Faber DS. Long-term potentiation of electrotonic coupling at mixed synapses. Nature. 1990;348:542–545. doi: 10.1038/348542a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarom Y, Llinás R. Long-term modifiability of anomalous and delayed rectification in guinea pig inferior olivary neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:1166–1177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-04-01166.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]