Abstract

Muramyl dipeptide (MDP) is a peptidoglycan moiety derived from commensal and pathogenic bacteria, and a ligand of its intracellular sensor NOD2. Mutations in NOD2 are highly associated with Crohn's disease (CD), which is characterized by dysregulated inflammation in the intestine. However, the mechanism linking abnormality of NOD2 signaling and inflammation has yet to be elucidated. Here we show that TAK1 is an essential intermediate of NOD2 signaling. We found that TAK1 deletion completely abolished MDP-NOD2 signaling, activation of NF-κB and MAPKs and subsequent induction of cytokines/chemokines, in keratinocytes. NOD2 and its downstream effector RICK associated with and activated TAK1. TAK1-deficiency also abolished MDP-induced NOD2 expression. Because mice with epidermal specific deletion of TAK1 develop severe inflammatory conditions, we propose that TAK1 and NOD2 signaling are important for maintaining normal homeostasis of the skin and its ablation may impair the skin barrier function leading to inflammation.

Introduction

Animals are constantly exposed to microorganisms present on the skin and the gastrointestinal tract. Detecting microorganisms and activating host immune systems to prevent their invasion are crucial for animal survival. The innate immune system, the first line of defense against invading microbial pathogens, uses pattern-recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to recognize microorganisms or their products on the cell membranes (1,2). In addition to TLRs, there is increasing evidence that intracellular recognition of bacteria is equally important in innate immune responses (3,4). NOD-like receptors (NLRs) are a family of cytosolic proteins that are involved in the recognition of intracellular bacteria (3,4). NOD2 is a member of the NLR protein family that contains a caspase recruitment domain (CARD) in the N-terminal region, a nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD) in the central region, and leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) in its C-terminus (3-5). NOD2 senses muramyl dipeptide (MDP), the minimal peptidoglycan (PGN) motif common to both gram-positive and negative bacteria, via the LRR domain (6,7). Upon MDP stimulation, NOD2 is oligomerized via the central NOD domain and recruits RICK, a serine/threonine kinase carrying a CARD domain at its C-terminus, through CARD-CARD interactions (8-11). The induction of NOD2/RICK signaling leads to activation of proinflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 (5,8,11). Studies using mice deficient in RICK have revealed that this kinase is essential for eliciting innate immunity in response to MDP (12). RICK has been also reported to function as a scaffold protein bringing NOD2 and IKK into close proximity (13) and to mediate ubiquitination of NEMO/IKKγ, a key component of NF-κB signaling complex (14). However, the exact molecular mechanism by which NOD2-RICK activates IKK-NF-κB and MAPK pathways remains undefined.

Initial studies revealed that NOD2 expression was restricted to monocytes/macrophages (5). However, additional studies showed that NOD2 is also expressed in several epithelial cells including enterocytes (15) and keratinocytes (16). Both enterocytes and keratinocytes are normally exposed to commensal bacteria and they are activated by bacterial components including MDP (16,17). Upon stimulation, enterocytes and keratinocytes produce anti-bacterial peptides as well as many cytokines/chemokines to recruit and activate immune cells in the intestine and skin, thereby preventing bacterial invasion and proliferation (17,18). Loss-of-function mutations of NOD2 are highly correlated with susceptibility of Crohn's disease (CD), a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease, which is characterized by chronic inflammation in the intestine (19,20). The mechanism by which ablation of MDP-NOD2 signaling can enhance inflammation in vivo has been a subject of much debate (21-23). One plausible mechanism is that failure of upregulation of anti-microbial peptides and/or cytokines/chemokines via MDP derived from commensal bacteria increases susceptibility to bacterial invasion, which may impair the epithelial barrier function and ultimately induce chronic inflammation. However, it has not been established whether loss of NOD2 signaling is causally involved in loss of epithelial barrier function in vivo.

Transforming growth factor-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1) is a member of the MAPKKK family and plays an essential role in tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin 1 (IL-1), and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways (24-27). In response to proinflammatory cytokines or TLR ligands, TAK1 is recruited to TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) and TAK1-binding proteins (TABs), which serve as adaptor proteins, and TAK1 in turn phosphorylates and activates IκB kinases (IKKs) as well as MAPKKs, which subsequently activate MAPKs JNK and p38. These pathways ultimately activate transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1. Besides its well-established role in proinflammatory cytokines and TLR signaling, TAK1 is also reported to be involved in the NOD2 signaling (28). TAK1 interacts with NOD2 and overexpression of dominant negative TAK1 inhibits NOD2-induced NF-κB activation. Recently, Windheim et al has reported that TAK1 is important for MDP signaling by using a selective inhibitor of TAK1 as well as in a model system using TAK1 knockout embryonic fibroblasts (29). However, the physiological roles of TAK1 in NOD2 signaling remain to be elucidated.

In this study, we determine the role of TAK1 in NOD2 signaling by utilizing TAK1 FL/FL (floxed) and Δ/Δ (knockout) keratinocytes generated by the Cre-LoxP system (30). We found that NOD2-induced innate immune responses are completely abolished in TAK1 Δ/Δ cells, and that TAK1 was activated upon stimulation of the MDP-NOD2-RICK pathway. In addition, we found that ablation of TAK1 blocked MDP-induced upregulation of NOD2. Our results indicate that TAK1 is not only an essential downstream molecule of NOD2-RICK signaling but also is involved in the regulation of NOD2 expression.

Experimental Procedures

Cells

TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes were isolated from TAK1 FL/FL and epithermal specific TAK1 deletion mice described in our previous publication (30). Spontaneously immortalized keratinocytes derived from the skin of postnatal day 0-2 mice were cultured in Ca2+-free minimal essential medium (Sigma) supplemented with 4% Chelex-treated bovine growth serum, 10 ng/ml of human epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen), 0.05 mM calcium chloride, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 33 °C in 8% CO2. Human embryonic kidney 293 and human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells were cultured in Dulbeccos's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% bovine growth serum (HyClone). 293 cells were transfected by the standard calcium phosphate precipitation method.

Antibodies, plasmids and reagents

Anti-NF-κB p65 (F-6), anti-NF-κB p50 (H-119), anti-NF-κB p52 (K-27), anti-IKKα (H-744), anti-IKKα/β (H-470), JNK (FL), anti-p38 (N-20) and anti-RICK (H-300) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies to phosphorylated JNK, phosphorylated p38 and phosphorylated TAK1 (Thr-187) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-Flag (Sigma) and Anti-HA (Covance) were used. Anti-TAK1 was described previously (24). Anti-human NOD2 affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibody was produced by immunizing a peptide DEEERASVLLGHSPGE (aa 11-26 of human NOD2). Human NOD2 cDNAs were subcloned to pCMV-HA vector. Flag-tagged RICK plasmids were described previously (20). pMX-puro-TAK1, -NOD2 and –RICK were generated by inserting the cDNAs into the pMX-puro vectors (31). MDP-LD, MDP-LL and LPS were purchased from Sigma.

Real-time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from skin, or culture keratinocytes using the RNeasy protect mini-kit (Qiagen). In order to obtain cDNA, 200ng of each RNA samples were reverstranscribed using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system. An Assays-on-Demand gene expression kit (Applied Biosystems) was used for detecting the expression of MIP2, TNF and NOD2. All samples were normalized to the signal generated from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cells were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and whole cell extracts were prepared using lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 12.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μM aprotinin, 0.5% Triton X-100). For co-precipitation assay, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of various antibodies and 15 μl of protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). The immunoprecipitates were washed three times with washing buffer (20 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl) and resuspended 2X SDS sample buffer and boiled. For detecting endogenous interaction between TAK1 and RICK, HT-29 cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT (pH 7.5) supplemented with protease inhibitors (10 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 20 μM aprotinin). Resuspended cells were lysed by passing through a 22-gauge needle 10 times and adding an equivalent volume of hypotonic buffer containing 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and 300 mM NaCl. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1.5 μg of control IgG or anti-RICK antibody. For immunoblotting, the immunoprecipitates or whole cell extracts were resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare). The membranes were immunoblotted with various antibodies, and the bound antibodies were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies against rabbit or mouse IgG using the ECL Western blotting system (GE Healthcare).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Whole cell extracts were prepared from keratinocytes stimulated with MDP for indicated time points. 32P-Labeled NF-κB oligonucleotides (Promega) were used for generating radiolabeled probe. 30 μg of WCEs were incubated with radiolabeled probe, 4% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 ng of poly(dI-dC) (GE Healthcare), and 10 μg of bovine serum albumin in a final volume of 20 μl for 20 min and subjected to electrophoresis on a 4% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel. For supershift assay, the whole cell extracts were incubated with 2 μg of NF-κB antibodies or control IgGs for 15 min prior to the addition of the labeled probe.

In vitro kinase assay

IKK complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKα and the immunoprecipitates were incubated with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]-ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) and 1 μg of bacterially expressed GST-IκB in 10 μl of kinase buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2 at 30°C for 30 min. Samples were then separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Retroviral infection

In order to obtain retrovirus carrying TAK1, NOD2 and RICK, EP2-293 cells (BD Biosciences) were transiently transfected with retroviral vectors, pMX-puro-TAK1, -NOD2 and -RICK. After 48 h culture, growth medium containing retrovirus was collected and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min to remove packaging cells. Keratinocytes were incubated with the collected virus-containing EP2-293 medium with 8 μg/ml polybrene for 24 h. Uninfected cells were removed by puromycin selection.

Results

MDP-mediated innate immune response is impaired in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes

We have previously generated TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes in which 37 amino acids including the ATP binding region of TAK1 are deleted by the Cre-loxP system resulting in the expression of kinase-dead TAK1 (TAK1 Δ) (30). In order to investigate the role of TAK1 in NOD2-mediated immune responses in epithelial cells, we used these TAK1 Δ/Δ and control TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes as a model system. Keratinocytes were stimulated with MDP (MDP-LD, an active isomer) and the expression of cytokine TNF and chemokine MIP2 (IL-8 in human) were measured using quantitative real-time PCR. We found that MDP was a potent inducer of cytokines/chemokines in keratinocytes (Fig. 1A). MDP-induced TNF and MIP2 expression was impaired in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes when compared with that observed in FL/FL keratinocytes (Fig. 1A). To confirm whether this impairment is caused by TAK1 deletion, we reintroduced wild-type TAK1 in TAK1 Δ/Δ cells by infection of retrovirus expressing wild type TAK1. TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes expressed the kinase-dead TAK1 at low levels presumably due to the unstable nature of mutant TAK1. The ectopically introduced TAK1 was expressed at levels similar to those found in TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes (Fig. 2A). Notably, the reintroduction of TAK1 into TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes restored MDP-induced proinflammatory cytokine expressions (Fig. 1A), which demonstrates that TAK1 is essential for MDP-mediated innate immune responses in keratinocytes. To confirm that MDP, but not contaminated bacterial component(s) such as LPS, mediated these responses, we examined the effect of a biological inactive isomer of MDP, MDP-LL and LPS on keratinocytes. Even at very high concentration, either MDP-LL or LPS did not induce expression of TNF or MIP2 in control TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that TAK1 is an essential intermediate for MDP signaling in keratinocytes leading to innate immune responses.

Fig. 1. MDP-induced expression of cytokine/chemokine in keratinocytes.

A. TAK1 FL/FL, Δ/Δ keratinocytes and TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes whose TAK1 expression was restored by retroviral infection (TAK1 Δ/Δ+TAK1) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of MDP for 6 h, and then MIP2 and TNF expression was examined by quantitative real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized with the levels of GAPDH. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using those of untreated TAK1 FL/FL or TAK1 Δ/Δ as base lines. Data are means ±s.d. of three independent samples and representative from three independent experiments with similar results.

B. TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of MDP (MDP-LD, active MDP isomer), MDP-LL (inactive MDP isomer) or LPS (100 μg/ml) for 6 h, and the expression of MIP2 and TNF was examined as described above.

Fig. 2. MDP-induced activation of NF-κB and MAPKs in keratinocytes.

A. TAK1 FL/FL, TAK1 Δ/Δ and TAK1 Δ/Δ+TAK1 keratinocytes were stimulated with MDP (20 μg/ml) for indicated times. Whole cell extracts were harvested from treated cells and the NF-κB-DNA binding activity was examined by EMSA. p65 immunoblotting was used for loading control for EMSA assay. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band.

B. Whole cell extracts from TAK1 FL/FL cells 6 h after MDP (10 μg/ml) stimulation were incubated with antibodies against NF-κB family proteins as well as control mouse or rabbit IgGs (mIgG, rIgG), and subjected to EMSA.

C. Whole cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKα and the IKK complex was subjected to an in vitro kinase assay using GST-IκB as an exogenous substrate. The amount of IKKα was analyzed by immunoblotting.

D,E. The whole cell extracts used for EMSA were subjected to immunoblotting using phospho-JNK, phospho-p38, JNK, and p38 antibodies. All results are representative of three independent experiments.

MDP-induced activation of NF-κB, JNK, and p38 is impaired in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes

To investigate the role of TAK1 in MDP-mediated intracellular signaling pathways, we examined the activation of NF-κB and MAPKs in TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes. In TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes, MDP markedly activated NF-κB DNA binding after 2-6 h incubation (Fig. 2A) and this was associated with translocation of the NF-κB subunit p65 into the nucleus (supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, MDP-induced NF-κB activation was not observed in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes (Fig. 2A and supplementary Fig. S1). Notably, the reintroduction of TAK1 restored the activation of NF-κB in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes (Fig. 2A). Gel supershift assay revealed that p65 homodimer is a major NF-κB complex in MDP-stimulated keratinocytes (Fig. 2B). To further confirm if MDP-induced NF-κB pathway is TAK1 dependent, we examined activation of IKK by in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 2C). IKK was activated at 2-6 h after MDP stimulation in TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes, whereas no activation was detected in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes. Activation of JNK and p38 MAPKs was determined by detecting the activated forms of JNK and p38 using phospho-specific antibodies. MDP activated JNK and p38 with a time course similar to that of NF-κB activation in control TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes, but the activation was completely abolished in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes (Fig. 2D and E). The reintroduction of TAK1 restored the activation of JNK and p38 (Fig. 2D and E). These results demonstrate that TAK1 is essential for the activation of both NF-κB and JNK/p38 following MDP stimulation in keratinocytes.

The time course of activation of NF-κB, JNK and p38 in MDP-stimulated keratinocytes was slow compared to that observed in TNF- or IL-1-stimulated cells. They are normally activated within 10-30 min after TNF or IL-1 treatment and downregulated afterwards (25,27). Because MDP induces strongly TNF (Fig. 1) but not IL-1 (data not shown), one possibility is that MDP-induced TNF may be responsible for this delayed activation. However, we found that MDP could activate NF-κB, JNK and p38 even in TNF receptor knockout keratinocytes with a time course similar to that observed in wild type keratinocytes (supplementary Fig. S2). Therefore, it is likely that MDP induces slowly TAK1 activation and subsequent downstream events.

NOD2 and RICK interact with TAK1

Our results shown indicate that TAK1 is a critical downstream target molecule of the MDP-NOD2-RICK signaling pathway. We examined next whether TAK1 can physically interact with NOD2 and RICK. Earlier studies reported that TAK1 interacts with NOD2 (28). We confirmed that TAK1 was co-precipitated with NOD2 when ectopically expressed in 293 cells (Fig. 3A, left panels). The reciprocal precipitation assay verified the TAK1-NOD2 interaction (Fig. 3A, right panels). TAK1 and RICK were also ectopically expressed in 293 cells and co-precipitation assay revealed that RICK associated with TAK1 (Fig. 3B). To further verify this interaction under physiological conditions, we examined the association of endogenous TAK1 with RICK in epithelial cells. For this purpose, we used the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29, because we found that HT-29 cells expressed RICK at higher levels than in keratinocytes (data not shown). Endogenous TAK1 was weakly co-precipitated with RICK in HT-29 cells and the interaction was enhanced by MDP treatment (Fig. 3C). Thus, TAK1 associates with RICK in epithelial cells, and MDP may enhance the interaction.

Fig. 3. NOD2 and RICK interact with TAK1.

A. 293 cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged TAK1 along with HA-tagged NOD2 or equal amount of empty vector. HA-NOD2 was immunoprecipitated, and immunoprecipitates and whole cell extracts (WCE) were analyzed by immunoblotting (left panels). The interaction was confirmed by reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation assay (right panels).

B. 293 cells were transiently transfected with Flag-tagged RICK along with HA-tagged TAK1 or equal amount of empty vector. TAK1-RICK interaction was tested as described above.

C. HT-29 cells were treated with MDP (10 μg/ml) for 6 h or left untreated, and whole cell extracts (WCE) was immunoprecipitated with anti-RICK antibody or same amount of control IgG. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

NOD2 and RICK activate TAK1

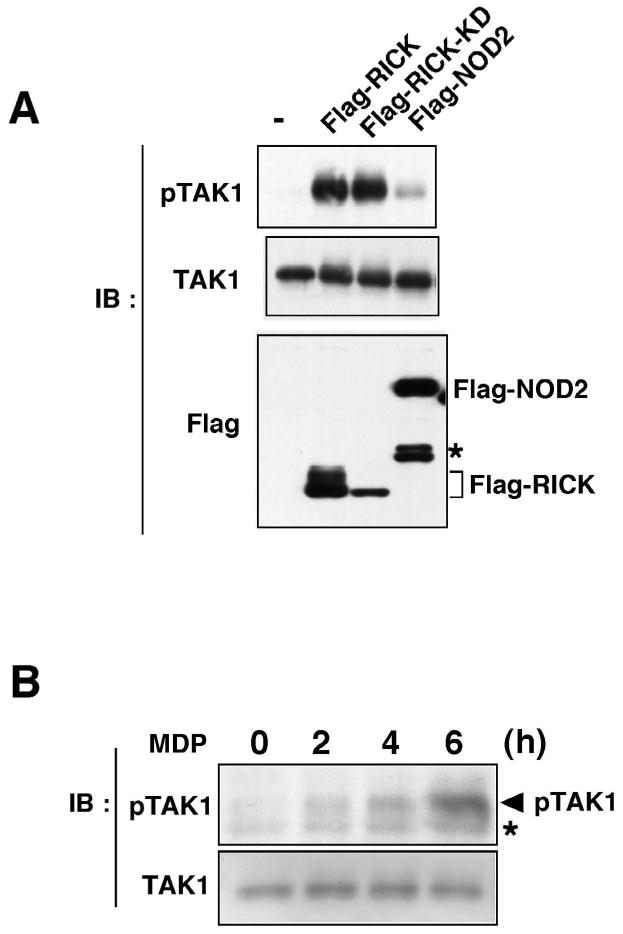

Although RICK is a kinase, it has been shown that its kinase activity is dispensable for activation of downstream events (32). This suggests that an unidentified kinase is responsible for phosphorylation of IKKs and MAPKKs leading to activation of NF-κB and MAPKs in NOD2-RICK pathway. TAK1 is a kinase that activates both IKK and MAPKKs in IL-1, TNF and TLR signaling pathways (24-26). Taken together with the results shown above, it is likely that TAK1 is activated by NOD2-RICK, and the TAK1 activation mediates both NF-κB and MAPKs pathways. TAK1 is activated by its autophosphorylation of amino acid residues within its activation loop including Thr-187 (33,34). We overexpressed NOD2 or RICK in 293 cells and detected the activated form of TAK1 using phospho-Thr-187 TAK1 antibody. NOD2 is normally activated by MDP-induced oligomerization, which can be mimicked by overexpression of NOD2 or RICK (5,8,9). We found that overexpression of both RICK wild type and kinase-dead mutant effectively activated TAK1 (Fig. 4A, lanes 1-3). NOD2 overexpression also induced TAK1 activation although at weaker levels than RICK (Fig. 4A, lane 4). To verify whether NOD2 signaling activates TAK1 under physiological conditions, we stimulated TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes with MDP and tested whether MDP could activate TAK1. We found that TAK1 was activated in keratinocytes after 2-6 h of MDP stimulation (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that MDP-NOD2-RICK activates TAK1, which leads to subsequent activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways.

Fig. 4. NOD2 and RICK activate TAK1.

A. 293 cells were transiently transfected with Flag-tagged RICK or NOD2. 48 h after transfection, whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting using phospho-TAK1 (Thr-187), TAK1 and Flag antibody. Asterisk indicates degraded forms of Flag-NOD2. Wild type RICK migrated as a smear due to its autophosphorylation.

B. TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes were stimulated with MDP (10 μg/ml) for the indicated times and whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting using phospho-TAK1 (Thr-187) or TAK1 antibody. All results are representative of three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band.

NOD2 and RICK induce innate immune responses in a TAK1 dependent manner

To further verify that TAK1 is an essential downstream effector of NOD2-RICK signaling, we examined the effect of NOD2 or RICK overexpression on cytokine/chemokine expression in TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes. To overexpress NOD2 and RICK in keratinocytes, we generated retroviruses expressing the puromycin resistant gene together with NOD2 or RICK gene. TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes were infected with the retroviruses and pools of keratinocytes expressing NOD2 or RICK were selected by puromycin. Overexpression of either NOD2 or RICK upregulated expression of MIP2 and TNF in TAK1 FL/FL keratinocytes. In contrast, no increase of MIP2 and TNF was detected in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes (Fig. 5A), even though the levels of NOD2 or RICK expression were similar in TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these results confirm that TAK1 is an essential downstream effector of NOD2-RICK signaling to induce innate immune responses.

Fig. 5. TAK1 is essential for the NOD2-RICK pathway in keratinocytes.

A. TAK1 FL/FL or Δ/Δ keratinocytes were infected with retrovirus carrying NOD2 or RICK. After puromycin selection, RNAs were isolated and used for quantitative real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized with the levels of GAPDH. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using those of the vector virus infected TAK1 FL/FL or TAK1 Δ/Δ as base lines. Data are means of duplicate samples and are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

B. The levels of overexpressed NOD2 or RICK in TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes were examined by immunoblotting.

TAK1 regulates NOD2 expression

It is known that the amount of NOD2 is upregulated by various stimuli including bacterial components in epithelial cells. Such upregulation of NOD2 results in amplification of the NOD2 signaling, which is probably important for effective responses against bacterial invasion (15,35). Because TAK1 plays important roles in MDP signaling, we hypothesized that TAK1 could be responsible for induction of NOD2. The levels of NOD2 mRNA in TAK1 FL/FL and Δ/Δ keratinocytes in response to MDP were examined (Fig. 6). We found that MDP could upregulate NOD2 in TAK1 FL/FL but not in TAK1 Δ/Δ keratinocytes. Thus, TAK1 is involved not only in NOD2-induced expression of cytokines/chemokines but also in the induction of NOD2 upon MDP stimulation.

Fig. 6. TAK1 regulates NOD2 expression.

TAK1 FL/FL, TAK1 Δ/Δ and TAK1 Δ/Δ+TAK1 keratinocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of MDP for 6 h, and RNAs were isolated and used for quantitative real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized with the levels of GAPDH. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using those of untreated TAK1 FL/FL or TAK1 Δ/Δ as base lines. Data are means ±s.d. of three independent samples and representative from two or three independent experiments with similar results.

Discussion

In this study, we determine the role of TAK1 in NOD2 signaling using TAK1 wild type and mutant keratinocytes as model cells. Based on our results, we propose a model of NOD2 signaling and regulation (Fig. 7). Upon MDP stimulation, NOD2 oligomerization induces assembly of a signaling complex including RICK and TAK1, which subsequently facilitates TAK1 autophosphorylation and its activation. TAK1 in turn activates both NF-κB and MAPK pathways leading to induction of innate immune responses. In addition, the TAK1 pathway upregulates the level of NOD2, which further amplifies NOD2 signaling. Thus, TAK1 is a master regulator of NOD2 signaling in epidermal cells.

Fig. 7. Model of NOD2 signaling pathway.

Recent studies have shown that K63-linked polyubiquitination of signaling molecules is involved in TAK1 activation in IL-1, TNF and TLR signaling (36). Stimulation of IL-1 receptor or Toll-like receptors leads to the activation of TNF receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6) E3 ubiquitin ligase, which induces K63-linked auto-polyubiquitination of TRAF6. The ubiquitinated TRAF6 is recruited to TAK1 complex containing a TAK1 binding protein, TAB2 or TAB3, through the interaction of the polyubiquitin chain with TAB2/3 (37,38). This interaction is believed to induce TAK1 autophosphorylation at Thr-187 and its kinase activation in IL-1 and TLR signaling. Therefore, it is likely that TRAF-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination and TAB2/3 participate in TAK1 activation in NOD2 signaling. During review of this manuscript, Abbott et al reported that NOD2 signaling induces polyubiquitination of TRAF6 (39). However, knockdown of TRAF6 did not impair NOD2-mediated NF-κB activation (39). We found that MDP could upregulate MIP2 and TNF in TAB2-deficient keratinocytes in a manner similar to that observed in wild type keratinocytes (data not shown). Collectively, the results suggest that multiple TRAF family proteins as well as TAB2 and TAB3 function to activate TAK1 in NOD2 signaling. Further studies are needed to define the molecular mechanism by which TAK1 is activated in NOD2 signaling.

The response of keratinocytes to MDP was somewhat unexpected in that epithelial cells in general including keratinocytes and enterocytes do not respond effectively to bacterial components. In our hands, keratinocytes did not respond to LPS at all. Because epithelial cells are constantly exposed to commensal bacteria, TLR signaling would be always activated if they could respond to LPS and other bacterial components. Therefore, this extremely low sensitivity of epithelial cells to TLR ligands is thought to be important for preventing dysregulated inflammation by commensal bacteria (40). MDP, a moiety of peptidoglycan (PGN), is a common component of Gram-positive and –negative bacteria including commensal bacteria located in the skin and the intestine. However, unlike TLR ligands, PGN needs to be incorporated into the cells and digested into MDP in order to be recognized by NOD2. These processes may reduce bacterium-induced innate immune responses in epithelial cells, but they may be sufficient and important to induce basal levels of cytokines/chemokines to maintain epithelial homeostasis.

MDP is a less potent inducer of cytokines/chemokines than TLR ligands including LPS in monocytes/macrophages (41). In contrast, we found that MDP is the most potent inducer of cytokines/chemokines in keratinocytes among the tested stimuli including LPS, TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β (data not shown). IL-1β and TNF can induce activation of NF-κB and JNK in keratinocytes in a transient manner peaking the response 10-30 min post-stimulation, whereas MDP activates the same TAK1-dependent pathways in a prolonged manner lasting at least 6 h after stimulation, which is associated with induction of TNF and MIP2 at high levels (Fig. 2 and unpublished data E.O. and J. N-T.). Although NOD2 is expressed in both monocytes/macrophages and epithelial cells, it is thought that, because the levels of NOD2 are generally low in epithelial cells, NOD2 may not play a major role in epithelial cells (42). However, our results raise the possibility that MDP-NOD2 signaling represents a major pathway of innate immune responses in keratinocytes.

We have previously shown that TAK1 deletion in keratinocytes results ablation of cytokine/chemokine expression in response to inflammatory stimuli such as IL-1β and TNF (30). In this study, we show that MDP-induced cytokines/chemokines are also abolished in TAK1 deficient keratinocytes. According to these results, we speculate that ablation of TAK1 would have a negative effect on inflammation in epithelial tissues. However, to our surprise, mice with epidermal specific deletion of TAK1 develop severe inflammatory conditions in skin at early neonatal stages (30). Thus, lack of TAK1 signaling that mediates NF-κB and MAPK signaling is associated with increased inflammation which is similar to that observed in the loss-of-function mutants of NOD2 that are associated with Crohn's disease. A number of studies using culture cells in vitro have demonstrated that NOD2 mediates proinflammatory signaling, however, the loss-of-function mutations of NOD2 are associated with inflammatory diseases in vivo in humans (21-23). These suggest that the NOD2-TAK1 signaling is important for the cell autonomous inflammatory signaling in epithelial cells, which appears critical for preventing dysregulated inflammation under the in vivo environment. Why and how cell autonomous inflammatory signaling in epithelial cells prevents overall inflammation? Medzhitov and colleagues have demonstrated that depletion of commensal bacteria causes hyper-susceptibility to epithelial injury (43). When the commensal bacteria are depleted or not recognized, mice develop severe inflammatory conditions upon injury. They have concluded that basal levels of cytokines/chemokines and possibly antibacterial peptides, which are induced by commensal bacteria under normal steady-state conditions, are essential for preventing dysregulated inflammation. The NOD2-TAK1 pathway may be involved in this steady-state epithelial homeostasis. Indeed, susceptibility to bacterial invasion is significantly increased in NOD2 -/- mice and production of antibacterial peptides in the intestine is reduced by NOD2 deletion (17). In conclusion, we propose that TAK1-mediated innate immune pathways including NOD2 pathway recognize commensal bacteria and function to maintain the basal levels of cytokines/chemokines under normal conditions, which is essential for epithelial homeostasis and for preventing bacterial invasion and subsequent dysregulated inflammation.

Similar to the TAK1 mutant skin, epithelium specific ablation of NF-κB pathway causes severe inflammation in the skin as well as in the intestine (44,45). Therefore, NOD2-TAK1-NF-κB may be a major pathway to prevent dysregulated inflammation in the skin and possibly in the intestine. However, while ablation of TAK1 or NF-κB alone causes severe inflammatory conditions (30,44,45), NOD2 knockout alone does not cause inflammation under normal conditions in mice (17,46). We assume that this difference is because TAK1-NF-κB participates in multiple signaling pathways activated by TLR ligands and proinflammatory cytokines, TNF and IL-1, whereas NOD2 is involved only in the MDP pathway. Interestingly, deletion of TNF receptor I can rescue the inflammatory phenotypes in the all NF-κB mutants and TAK1 mutant mice (30,44,45), indicating that TNF is the major mediator of inflammation caused by dysfunction of TAK1-NF-κB signaling. In humans, inhibition of TNF is one of the most effective treatments of CD. These lead us to further speculate that the pathology of CD may be associated with dysregulation of TAK1-NF-κB pathway activated by several stimuli including NOD2 in epithelial cells. Our results warrant further study to determine the relationship between TAK1 pathway and the pathogenesis of CD.

Supplementary Material

The abbreviations used are

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- MDP

muramyl dipeptide

- PGN

peptideglycan

- CD

Crohn's disease

Footnotes

We thank Drs. C. Jobin and K. Linder for discussion, and T. Kitamura for providing vectors. This work was supported by Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America and National Institutes of Health Grant GM068812 (to J. N-T).

References

- 1.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeda K, Akira S. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inohara, Chamaillard, McDonald C, Nunez G. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:355–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi KS, Eynon EE, Flavell RA. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:652–654. doi: 10.1038/ni0703-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogura Y, Inohara N, Benito A, Chen FF, Yamaoka S, Nunez G. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4812–4818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, Foster SJ, Moran AP, Fernandez-Luna JL, Nunez G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5509–5512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inohara N, del Peso L, Koseki T, Chen S, Nunez G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12296–12300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy JV, Ni J, Dixit VM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16968–16975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thome M, Hofmann K, Burns K, Martinon F, Bodmer JL, Mattmann C, Tschopp J. Curr Biol. 1998;8:885–888. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Immunol Rev. 2000;173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JH, Kim YG, McDonald C, Kanneganti TD, Hasegawa M, Body-Malapel M, Inohara N, Nunez G. J Immunol. 2007;178:2380–2386. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inohara N, Koseki T, Lin J, del Peso L, Lucas PC, Chen FF, Ogura Y, Nunez G. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27823–27831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbott DW, Wilkins A, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2217–2227. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez O, Pipaon C, Inohara N, Fontalba A, Ogura Y, Prosper F, Nunez G, Fernandez-Luna JL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41701–41705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voss E, Wehkamp J, Wehkamp K, Stange EF, Schroder JM, Harder J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2005–2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nunez G, Flavell RA. Science. 2005;307:731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Weichenthal M, Schwab M, Schaffeler E, Schlee M, Herrlinger KR, Stallmach A, Noack F, Fritz P, Schroder JM, Bevins CL, Fellermann K, Stange EF. Gut. 2004;53:1658–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.032805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouma G, Strober W. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:521–533. doi: 10.1038/nri1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi K, Inohara N, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Nunez G, Janeway CA, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Nature. 2002;416:194–199. doi: 10.1038/416194a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckmann L, Karin M. Immunity. 2005;22:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugot JP. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1072:9–18. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelsall B. Nat Med. 2005;11:383–384. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T, Matsumoto K, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1087–1095. doi: 10.1038/ni1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shim JH, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, Lee KY, Bussey C, Steckel M, Tanaka N, Yamada G, Akira S, Matsumoto K, Ghosh S. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2668–2681. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takaesu G, Surabhi RM, Park KJ, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Gaynor RB. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CM, Gong Y, Zhang M, Chen JJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25876–25882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Windheim M, Lang C, Peggie M, Cummings L, Cohen P. Biochem J. 2007;404:179–190. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omori E, Matsumoto K, Sanjo H, Sato S, Akira S, Smart RC, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19610–19617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603384200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitamura T. Int J Hematol. 1998;67:351–359. doi: 10.1016/s0925-5710(98)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu C, Wang A, Dorsch M, Tian J, Nagashima K, Coyle AJ, Jaffee B, Ocain TD, Xu Y. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16278–16283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajino T, Ren H, Iemura S, Natsume T, Stefansson B, Brautigan DL, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39891–39896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608155200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kishimoto K, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7359–7364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenstiel P, Fantini M, Brautigam K, Kuhbacher T, Waetzig GH, Seegert D, Schreiber S. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1001–1009. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen ZJ, Bhoj V, Seth RB. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:687–692. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kishida S, Sanjo H, Akira S, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. Genes Cells. 2005;10:447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanayama A, Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Hong M, Shaito A, Chiu YH, Deng L, Chen ZJ. Mol Cell. 2004;15:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbott DW, Yang Y, Hutti JE, Madhavarapu S, Kelliher MA, Cantley LC. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00270-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lotz M, Gutle D, Walther S, Menard S, Bogdan C, Hornef MW. J Exp Med. 2006;203:973–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe T, Kitani A, Murray PJ, Strober W. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:800–808. doi: 10.1038/ni1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A, Watanabe T. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nenci A, Huth M, Funteh A, Schmidt-Supprian M, Bloch W, Metzger D, Chambon P, Rajewsky K, Krieg T, Haase I, Pasparakis M. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:531–542. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, Gareus R, van Loo G, Danese S, Huth M, Nikolaev A, Neufert C, Madison B, Gumucio D, Neurath MF, Pasparakis M. Nature. 2007;446:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature05698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pauleau AL, Murray PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7531–7539. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7531-7539.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.