Abstract

Maltose-binding protein (MBP or MalE) of Escherichia coli is the periplasmic receptor of the maltose transport system. MalE31, a defective folding mutant of MalE carrying sequence changes Gly 32→Asp and Ile 33→Pro, is either degraded or forms inclusion bodies following its export to the periplasmic compartment. We have shown previously that overexpression of FkpA, a heat-shock periplasmic peptidyl-prolyl isomerase with chaperone activity, suppresses MalE31 misfolding. Here, we have exploited this property to characterize the maltose transport activity of MalE31 in whole cells. MalE31 displays defective transport behavior, even though it retains maltose-binding activity comparable with that of the wild-type protein. Because the mutated residues are in a region on the surface of MalE not identified previously as important for maltose transport, we have solved the crystal structure of MalE31 in the maltose-bound state in order to characterize the effects of these changes. The structure was determined by molecular replacement methods and refined to 1.85 Å resolution. The conformation of MalE31 closely resembles that of wild-type MalE, with very small displacements of the mutated residues located in the loop connecting the first α-helix to the first β-strand. The structural and functional characterization provides experimental evidence that MalE31 can attain a wild-type folded conformation, and suggest that the mutated sites are probably involved in the interactions with the membrane components of the maltose transport system.

Keywords: Crystal structure, maltose-binding protein, maltose transport, periplasm, protein misfolding

The proper functioning of extra-cytoplasmic proteins requires their export to, and productive folding in, the correct cellular compartment. In Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, proteins destined for the periplasm or outer membrane are synthesized in the cytoplasm as precursors carrying an amino-terminal signal sequence. These preproteins, maintained in an export-competent conformation, are targeted selectively to the translocation machinery in the cytoplasmic membrane. After translocation and signal sequence cleavage, the newly exported mature proteins are sorted, folded, and assembled in the periplasm and outer membrane. In contrast to the folding and targeting of nascent precursors emerging from the ribosomes, little is known about these processes in the periplasm after exported proteins are released from the translocation machinery. However, recent studies of signal transduction pathways in the extra-cytoplasmic stress response to misfolded envelope proteins have identified and characterized several genes encoding proteins involved in the biogenesis of periplasmic and outer membrane proteins (Danese and Silhavy 1998).

To better understand the process of protein folding in the bacterial periplasm, we have used a folding-defective mutant, MalE31, of the maltose-binding protein MalE (or MBP) from E. coli as a model. MalE functions in the periplasm of E. coli by binding maltose and maltodextrins, and presenting these substrates to the inner membrane protein complex MalFGK2, a transporter belonging to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family. MalFGK2 comprises two integral membrane subunits, MalF and MalG, and two copies of a cytoplasmic ATPase subunit, MalK (Boos and Shuman 1998). MalE functions as the primary receptor for maltose, undergoing a conformational change to generate a high-affinity complex with the ligand (Sharff et al. 1992). Ligand-bound MalE interacts with MalF and MalG to stimulate ATP hydrolysis by MalK, leading to the active transport of maltose to the cytoplasm (Davidson et al. 1992). The overall structure of MalE consists of two globular domains formed by discontinuous segments of the primary structure, the N-domain (residues 1–109 and 264–309) and the C-domain (residues 114–258 and 316–370). These domains contain a central β-sheet flanked by two or three α-helices (Spurlino et al. 1991). The maltose-binding site is located at the base of a deep groove formed between the two domains.

We have previously identified amino acid substitutions that alter the folding pathway of MalE (Betton et al. 1996). Among these mutations, the most defective folding variant, MalE31, corresponds to the double substitution of Gly 32→Asp and Ile 33→Pro in a turn connecting helix α1 to strand βB of the N-domain, which is distant from the ligand-binding site (Betton et al. 1996). On the basis of the kinetics of signal peptide processing, the MalE31 precursor was shown to be correctly exported in vivo, but misfolding of the mature protein led to the formation of inclusion bodies in the periplasm (Betton and Hofnung 1996). At low levels of expression, the misfolded MalE31 protein was completely degraded by the DegP protease (Betton et al. 1998), a periplasmic heat-shock protein whose proteolytic activity is essential for the survival of E. coli at high temperatures (Lipinska et al. 1989; Strauch et al. 1989). A mechanism involving kinetic competition between productive folding, aggregation, and degradation was proposed to explain the different fates of the newly translocated MalE31 (Betton et al. 1998). One major consequence for the cells overproducing MalE31 is an increased envelope stress response (Missiakas et al. 1996).

MalE31 can be purified by affinity chromatography from inclusion bodies after a urea-solubilization step (Betton and Hofnung 1996). Because of the competing off-pathway aggregation reaction also present in the in vitro folding process, the unfolding and refolding transitions of MalE31, under equilibrium conditions, did not coincide and led to hysteresis (Raffy et al. 1998). However, unfolding and refolding kinetics of MalE31 were consistent with a decreased stability of folding intermediates.

To investigate the structural consequences of the mutation, we have solved the crystal structure of the maltose-bound MalE31. The results of the crystallographic study and functional characterizations reported here show that MalE31 retains the native structure and wild-type maltose-binding affinity but displays severe defects in transport, both in vivo and in vitro. These results support a model in which the effect of the mutation on the structure is exerted at the level of folding intermediates, rather than that of the native conformation. In addition, we conclude that the site of mutation in the first α/β turn of the N-domain is probably involved in the interactions with the membrane components of the maltose transport system.

Results

Maltose transport in whole cells

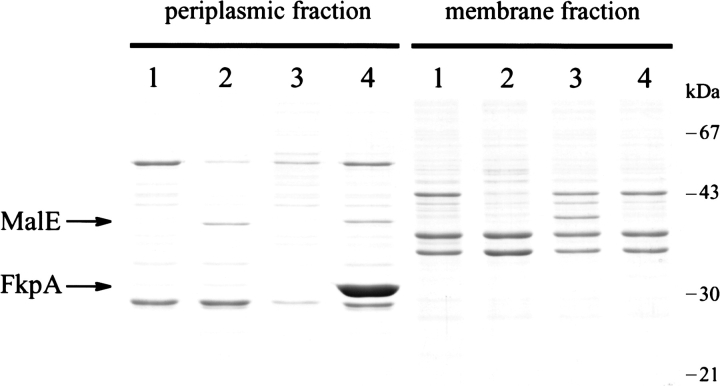

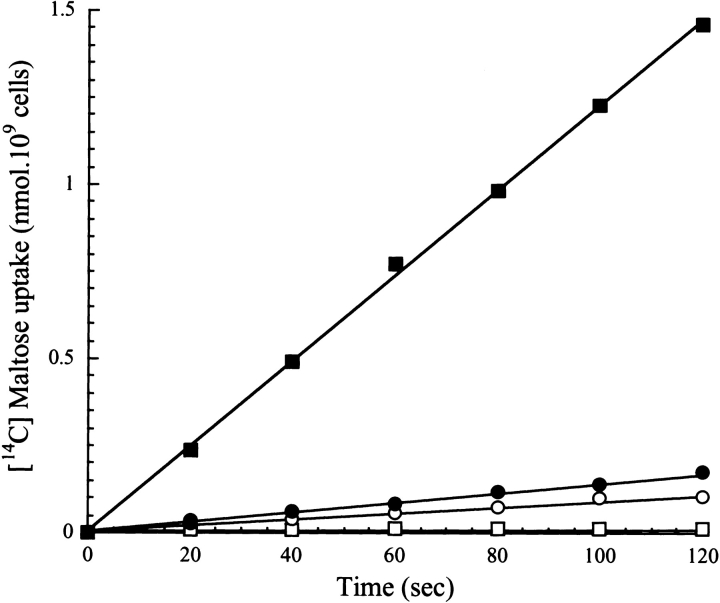

Although MalE31 is correctly exported to the periplasm, the failure of mature protein to fold properly results in a maltose-defective phenotype of cells that overexpress this mutant (Betton et al. 1996). Nearly all of the newly translocated MalE31 is either aggregated or degraded, and the very low amount of native periplasmic protein that escapes misfolding is unable to complement maltose utilization in malE minus strains. However, we have demonstrated recently that overexpression of the periplasmic peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, FkpA, both suppresses aggregation and facilitates correct folding of MalE31 (Arie et al. 2001). We have exploited this property to characterize the maltose transport activity of MalE31 in whole cells. First, we determined the level of MalE31 in subcellular fractions prepared from a strain carrying the chromosomal malE31 mutation (JMB5), transformed with either the control plasmid (pTrc99A) or a plasmid overproducing FkpA (pTfkp). We compared this level with that of wild-type MalE produced from the noninduced strain MC4100. Because export of MalE31 is fully efficient, subcellular fractionation of periplasmic and membrane fractions from spheroplasts gives a quantitative measure of the soluble/insoluble distribution (Fig. 1 ▶). The overexpression of fkpA significantly enhanced the yield of soluble MalE31 in the periplasm. Under these conditions, the quantitative densitometry of bands from the gel shown in Figure 1 ▶ indicated that the level of periplasmic MalE31 is 1.5-fold higher than in the wild type produced from MC4100 cells. Second, maltose transport activity of these strains was determined by measuring the initial rate of maltose uptake at 2 μM external maltose (Fig. 2 ▶). The strain containing the nonpolar deletion malE444 (PD28) did not transport maltose, whereas the malE31-containing strain exhibited only 7% of the wild-type rate of transport determined for MC4100 cells under the same conditions. When FkpA was overproduced, however, this rate did not increase significantly as would be expected from the amounts of periplasmic MalE31. These results show, for the first time, that the mutated residues in MalE31 may also be involved in maltose transport.

Figure 1.

FkpA prevents MalE31 aggregation. Cells expressing chromosomally encoded MalE-wt or MalE31, transformed by pTrc99 or pTfkp, were grown in rich medium at 37°C for 3 h, and then fractionated from spheroplasts. Periplasmic (soluble) and membrane (insoluble) fractions, corresponding to 5 × 109 cells, were analyzed on SDS–polyacrylamide (12.5%) gel stained by Coomassie blue. (Lane 1), Strain PD28 (ΔmalE) carrying pTrc99. (Lane 2) Strain MC4100 (malE) carrying pTrc99. (Lane 3) Strain JMB5 (malE31) carrying pTrc99. (Lane 4) JMB5 cells carrying pTfkp.

Figure 2.

Cells expressing folded MalE31 do not transport maltose. The initial rates of maltose transport were determined at a substrate concentration of 2 μM using cells grown as described for the experiment shown in Figure 1 ▶. Open squares indicate Strain PD28 (ΔmalE) carrying pTrc99; filled squares indicate Strain MC4100 (malE) carrying pTrc99; open circles indicate Strain JMB5 (malE31) carrying pTrc99; and filled circles indicate JMB5 cells carrying pTfkp.

Maltose binding of MalE31

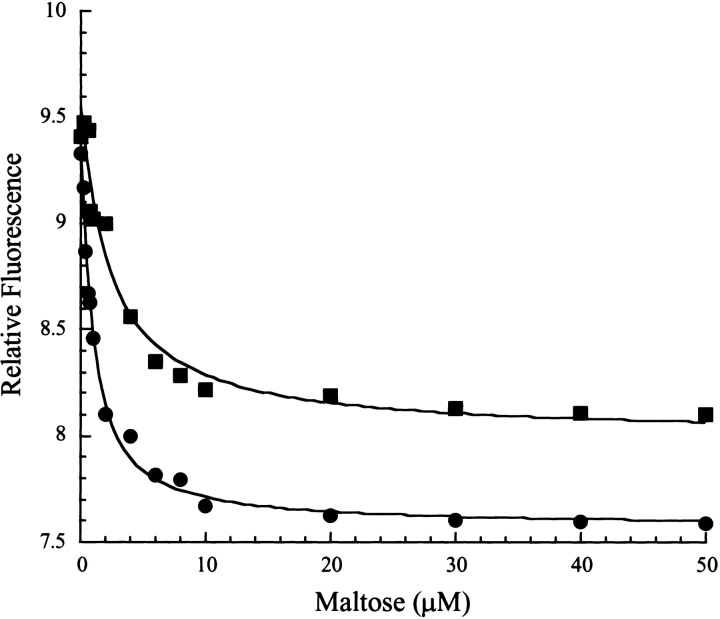

Previously, we had shown that periplasmic fractions containing MalE31 solubilized by FkpA retain maltose-binding activity (Arie et al. 2001), but the affinity of these species for maltose was not determined. To measure dissociation constants, maltose-free wild-type and MalE31 proteins from periplasmic fractions, prepared as shown in Figure 1 ▶, were purified by use of two conventional chromatographic steps. Because the tryptophan fluorescence properties of MalE31 were not modified (data not shown), maltose binding was monitored by following the decrease of emission intensity at 345 nm (Fig. 3 ▶). For both wild-type MalE and MalE31, experimental data could be accurately fitted to a single one-step binding process. Dissociation constants were consistent with values determined previously for proteins purified on an amylose affinity column (Raffy et al. 1998), showing a slightly lower affinity in the case of MalE31 (2 ± 0.4 μM) as compared with the wild-type (0.8 ± 0.1 μM). The maximum fluorescence change from unbound to maltose-saturated protein was 10% lower for MalE31 as compared with the wild-type protein, both binding measurements being carried out at the same nominal protein concentration (0.5 μM). Although it is possible that some nonfunctional proteins were present in the purified pool of MalE31, the small difference in maltose affinity between MalE31 and wild-type MalE cannot account for the highly altered transport properties of MalE31 in intact cells.

Figure 3.

Folded MalE31 retains maltose affinity. The affinity of wild-type MalE and MalE31 for maltose was determined by fluorescence titration. The excitation wavelength was 290 nm and the intensity of fluorescence emission was recorded at 345 nm. Filled circles indicate wild-type MalE (0.5 μM); filled squares indicate MalE31 (0.5 μM). Data were analyzed according to Equation 1, as described in Materials and Methods. Solid lines through the data points represent the best fits.

Maltose transport in proteoliposomes

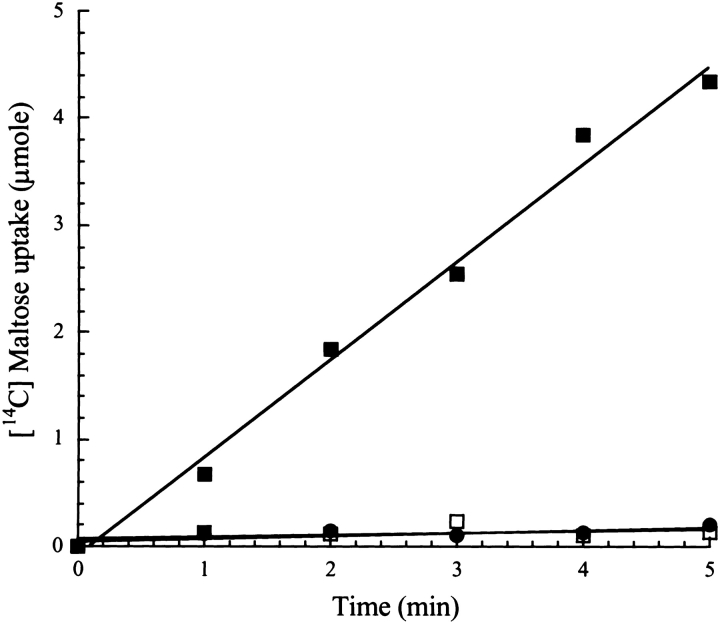

To examine whether the defective maltose transport activity observed in whole cells was an effect of the solubility-enhancing property of FkpA, we tested this activity in vitro with a reconstituted MalFGK2 transporter. Proteoliposomes containing MalFGK2 incubated with wild-type MalE exhibited maltose uptake at a rate of 1 μmole/min (Fig. 4 ▶). However, when MalE31 (or MalE211, a MalE mutant that has both altered binding and transport activities) (Duplay et al. 1987), was added to proteoliposomes, no maltose uptake was observed, thus confirming that native MalE31 is unable to function correctly. Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that residues 32 and 33 are involved in the interactions with the membrane transporter.

Figure 4.

Maltose uptake into proteoliposome vesicles. Solubilized membrane proteins from strain ED169, overexpressing malF, malG, and malK, were reconstituted in proteoliposomes, incubated with 3 μM purified wild-type MalE (filled squares), MalE31 (filled circles), or MalE211 (open squares) in the presence of 2 μM maltose. [14C] maltose uptake was measured by filtration assays, as described in Materials and Methods.

Structural comparison of MalE31 with wild-type MalE

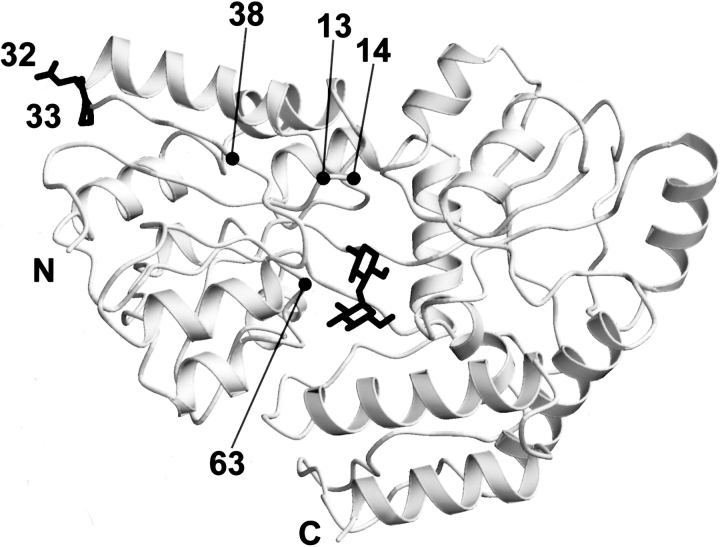

To provide precise information on the structural effects of the mutations Gly 32→Asp and Ile 33→Pro, we have solved the crystal structure of the liganded form of MalE31. The protein is in the closed conformation, as expected from the presence of bound maltose (Fig. 5 ▶). The root mean square difference (r.m.s.d.) between the α-carbon positions of the two nearly identical molecules of MalE31 in the asymetric unit and wild-type MalE (PDB code 1anf) is 0.44 Å. The first five residues were not included in the calculation because these have very high temperature factors in the wild-type structure. There is a small difference in the relative orientation of domains between MalE31 and wild-type MalE; after superimposing their N-domains upon each other (residues 6–109 and 264–309, α-carbon r.m.s.d. 0.38 Å), an additional rotation of 1.3° is required to bring their C-domains (residues 114–258 and 316–369, α-carbon r.m.s.d. 0.35 Å) into optimal coincidence.

Figure 5.

Schematic view of the MalE31 structure. The mutated residues at positions 32 and 33 (top left) occur in an αβ turn at an exposed position in the amino-terminal domain. Positions 13, 14, 38, and 63 located in the N-domain correspond to mutations affecting maltose transport (see text). The bound maltose substrate (middle) is located in a deep cleft between the amino- and carboxy-terminal domains.

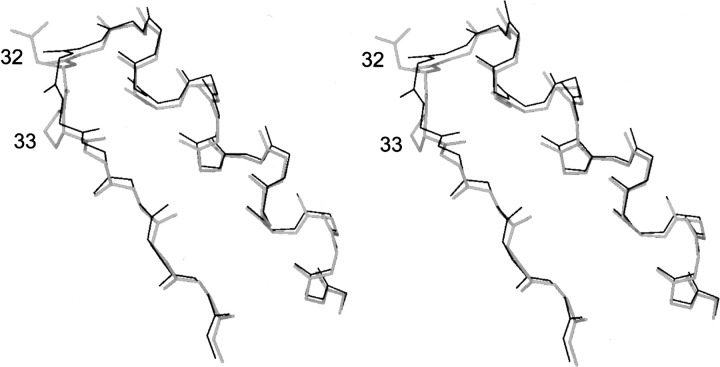

Apart from the amino terminus, four other regions of MalE31 stand out as deviating significantly from the wild-type structure. These regions, in which the α-carbon positions differ by more than twice the r.m.s.d., are as follows: residues 32–33 (r.m.s.d. 1.44–1.50 Å), residue 78 (1.02 Å), residues 172–175 (1.19–2.14 Å), and residues 312–313 (0.95–1.36 Å). The segment 172–175 is at the extremity of an external β-hairpin strand that makes no strong stabilizing contacts with the core of the molecule. The high-temperature factors of this segment suggest that it is relatively mobile, accounting for the structural difference in this region. The large departure from ideal stereochemistry in the region 312–313 of the 1anf model probably accounts for the difference observed here between the two structures. There is no apparent explanation, however, for the deviation at residue 78. The remaining segment, residues 32–33, carries the mutations Gly 32→Asp and Ile 33→Pro. The dihedral angles [φ,ϕ] change from [88°, −7°] to [117°, −46°] for residue 32, and from [−93°, 119°] to [−70°, 136°] for residue 33, when going from wild-type MalE to MalE31. These changes do not lead to significant alteration to the overall main-chain conformation in this part of the molecule (Fig. 6 ▶). The dihedral angles of residue 33 in MalE31 are thus more consistent with the stereochemical constraints of proline (ϕ = −63° ± 15°) (MacArthur and Thornton 1991). On the other hand, Asp 32 occurs in an energetically unfavorable region of the Ramachrandran plot. However, as this residue is positioned in well-defined electron density, its main-chain conformation can be assigned with confidence. The small differences in this region, compared with wild-type MalE, can be explained by intermolecular polar contacts formed by the main-chain carbonyl groups of residues 29 and 30. In both independent molecules of MalE31, these residues make a bifurcated hydrogen bond with Nɛ2 of His 39 of a neighboring molecule, and Oδ1 of Asp 32, which forms a hydrogen bond with OH of Tyr 17 of the same neighboring molecule. The effect of the intermolecular contacts in the crystal structure is to draw the loop toward the neighboring molecule, and it can be expected that this region of MalE31 would be intrinsically closer to the wild-type structure in the absence of these interactions.

Figure 6.

Stereo view of the mutated residues Asp32 and Pro33, and the main-chain atoms of the α1–βB turn (shown in thick trace), and comparison with the corresponding main-chain atoms (thin trace) of the superimposed wild-type structure.

Discussion

Structural analysis

The crystal structure of MalE31 shows that the mutations, Gly 32→Asp and Ile 33→Pro, do not prevent the protein from attaining a stable conformation that is essentially identical to that of the wild-type protein. The possibility that the Ile 33→Pro mutation could conceivably introduce an additional cis-trans peptide-bond isomerization step has been ruled out as the cause of MalE31 misfolding. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase FkpA prevents nonproductive folding of MalE31 by chaperone activity that is independent of its cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase function, as increased amounts of FkpA augment the yield of correctly folded MalE31, but its presence has no affect on the folding rate (Arie et al. 2001).

The location of the mutated residues in MalE31 between the two secondary structural elements, helix α1 and strand βB, and the nature of the amino acid changes, suggest an alternative explanation for the tendency of this mutant to misfold after export and release in the periplasmic compartment of E. coli. Both mutations introduce a loss of conformational freedom in the polypeptide backbone that could be crucial in the folding pathway as follows: the replacement of glycine, the least-restricted amino acid for allowed [ϕ, φ] dihedral angles, by aspartate at position 32; and the replacement of isoleucine at position 33 by proline, the amino acid with the highest conformational restriction (MacArthur and Thornton 1991). Mutational studies suggest, however, that the introduction of Pro 33 is the more critical factor, because all phenotypes carrying this mutation are Mal− (except Gly 32–Pro 33), whereas most phenotypes with position 32 different from glycine are Mal+ (Betton et al. 1996). The significance of conformational restriction by proline is also reinforced by the absence of Mal+ phenotypes carrying the mutation Gly 32→Pro.

Another cause of MalE31 misfolding, which does not preclude the importance of reduced conformational freedom of the polypeptide backbone of the mutant, could arise from the effect of the mutations on the stability of the protein in its folded state or in critical folding intermediate states. In the wild-type protein, Thr 31 can form a stabilizing interaction between helix α1 and strand βB through hydrogen bonds made between Oγ1 and both the carbonyl oxygen of residue 27 and the amide nitrogen of residue 33. Although these interactions are absent in the wild-type model 1anf, they are present in the structure of the hybrid MalE-B363 (Protein Data Bank entry 1a7l; Saul et al. 1998). Because the amide group of proline cannot form a hydrogen bond, mutants with Pro 33 cannot make this polar interaction with Thr 31. This could also explain why all mutants bearing proline at this site, with the exception of Gly 32–Pro 33, are Mal−. It could be argued that the mutation Gly 32→Asp also raises the energy with respect to wild type, as this places a negative charge at the carboxyl terminus, or negative dipole end, of helix α1. This factor is probably not very important, however, as all mutants that introduce a negatively charged residue at position 32, and with residue 33 different from proline, are Mal+ (Betton et al. 1996).

Implications for understanding protein misfolding in vivo

The results presented here show that the amino acid substitutions in the first αβ turn of the N-domain, which play a critical role in MalE31 folding, induce only small differences in conformation of MalE31 compared with the wild-type structure. Both genetic and biochemical experiments (Betton and Hofnung 1996; Betton et al. 1996, 1998; Raffy et al. 1998) suggest that MalE31 aggregation and inclusion body formation represent a specific self-association pathway of a folding intermediate. The influence of genetic mutations on the propensity to aggregate, or to form inclusion bodies, has been well studied for the thermostable tailspike adhesin of phage P22 (Betts and King 1999). The clear difference in physical properties between the native state and folding intermediates allowed the isolation of a class of temperature-sensitive folding mutations (tsf) that alters the folding pathway of this protein. Tsf mutations reduce yields of folded protein at high temperature and enhance aggregation (Haase-Pettingell and King 1988), whereas mutations isolated as intragenic second-site suppressors of the tsf phenotype have the opposite effect (Mitraki et al. 1991). Tsf mutations identified residues necessary for directing the partially folded polypeptide chain past the junction to the inclusion body trap at high temperatures, but not at lower temperatures. Suppressor mutations identified residues that could correct the folding defects of most tsf mutations at many different sites by inhibiting entry of the junctional folding intermediate into the inclusion body pathway. Nevertheless, both types of mutation have little effect on the native state of the tailspike protein. Although the pathways are different, the mechanism of aggregation of the tailspike tsf mutants and MalE31 appears to be the same, self-association and aggregation of partially folded intermediates.

The relationship of inclusion body formation to in vitro MalE31 folding has been established previously (Raffy et al. 1998). The increase of light scattering during the refolding of MalE31 clearly indicated that a competing aggregation reaction occurs along the folding pathway. Consequently, the equilibrium unfolding–refolding transitions, induced by varying the concentration of guanidium chloride, did not coincide (Raffy et al. 1998), and the thermodynamic stability of MalE31 could not be determined by this classical method. However, the unfolding kinetics did reflect a difference in stability between the native state and the rate-limiting transition state of unfolding, and there was a good correlation, in general, between the unfolding rates and the free energies of folding. Because MalE31 exhibited an unaltered unfolding rate but a reduced refolding rate, when compared with the wild-type MalE in guanidine-induced denaturation (Raffy et al. 1998), the intermediate in the MalE31-folding pathway, rather than its native state, seemed to be destabilized. The crystal structure of MalE31 shows that the mutated αβ turn is not different from MalE in tertiary structure. The major effects of the malE31 mutation on the folding pathway were hardly predictable even with the availability of a well-refined structure of MalE31. Although the crystal structure of MalE31 gives no direct details on the mechanism of misfolding in the bacterial periplasm, its comparison with the wild-type MalE structure does suggest that certain structural factors could account for this phenomenon. In addition, the structural results provide a basis for further study of the interaction of MalE with MalG and MalF.

Interaction site with MalG and MalF

MalE in the closed-liganded conformation initiates transport by interacting with MalFGK2. Although only the closed conformation of MalE possesses the correct geometry for productive binding to the membrane components (Duan et al. 2001), the exact sites of interaction are still unknown. Several residues of MalE that are important in transport, but not in maltose binding, have been isolated by two different genetic approaches. In the first, a strain in which the malE gene was deleted was used to select for mutants of MalFGK2 that were able to grow in maltose minimum medium (Shuman 1982; Treptow and Shuman 1985). When wild-type MalE was reintroduced, the cells were unable to grow on maltose minimum medium, presumably due to formation of a nonproductive complex between MalE and the mutant membrane components. This property was used to locate regions on MalE that were involved in binding to MalFGK2 (Treptow and Shuman 1988; Hor and Shuman 1993). Several MalE suppressor mutants were found, corresponding to positions 13, 14, and 63 in the N-domain (Fig. 5 ▶) and positions 155, 210, and 230 in the C-domain. The second genetic method was the selection of MalE mutants that could inhibit growth on maltose minimum medium when coexpressed with reduced levels of wild-type MalE in a wild-type MalFGK2 background (Hor and Shuman 1993). Such mutants are termed dominant-negative and correspond to Glu 38→Lys, Tyr 210→Cys, and Trp 230→Arg. Interestingly, it was found that, under appropriate assay conditions, certain suppressors could act as dominant negative and vice-versa. These mutations, when mapped onto the structure, are clustered on a single face of the protein surface at the top end of the amino- and carboxy-terminal domains on the same side as the opening of the cleft (Spurlino et al. 1991; Sharff et al. 1992). None of these genetic studies, however, identified residues in the modified turn of MalE31. It has not been possible to isolate such mutations by genetic selection or screening methods based on growth in the presence of maltose, because MalE31 is either degraded or forms inclusion bodies following its export to the bacterial periplasm. A mutation that prevents protein folding is generally excluded from such genetic approaches. In contrast to residues 13, 14, 38, 63, 155, 210, and 230, the modified MalE31 residues, 32 and 33, are located in a surface turn that is distant from the cleft. On the other hand, these modified residues are close to the region where the dominant-negative allele corresponding to Glu 38→Lys is found, and are opposite the hinge between the two structural domains. It is therefore possible that the altered interactions with MalF and MalG exhibited by MalE31 could be due to indirect effects on the conformation of the interaction site.

Finally, a highly conserved sequence motif spanning residues 27–35 observed between MalE and PotD, the polyamine-binding protein, suggests a common functional role in the transport of these two systems (Sugiyama et al. 1996). Our results are consistent with this suggestion, and the recent finding that MalE becomes tightly associated with the solubilized MalFGK2 membrane transporter in the presence of vanadate (Chen et al. 2001) indicates that these interactions could be studied in vitro.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

E. coli MC4100 (araD139 ΔlacU169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR) was obtained from our laboratory collection. The two isogenic strains PD28 (ΔmalE444 malTc) and JMB5 (MC4100 malE31 malTc) have been described previously (Betton and Hofnung 1996; Arie et al. 2001). The malTc allele confers constitutive expression on the maltose operons (Debarbouille et al. 1978). ED169 (Mourez et al. 1997), a ΔmalB107 derivative of MC4100, lacking the whole malB region encoding the maltose transport system, was used to prepare proteoliposomes.

Plasmid pTfkp, a derivative of the expression vector pTrc99 (Amersham Biosciences), carries the fkpA gene under the control of the inducible Ptrc promoter (Arie et al. 2001). Plasmids pTAZFGQ, a derivative of pTZ18-R (Amersham Biosciences), containing the malF and malG genes under the control of the Ptac promoter, and plasmid pACYK, a derivative of pACYC184 (New England Biolabs) containing the malK gene downstream of the Ptrc promoter, have been described previously (Mourez et al. 1997). Plasmid p31H is a pBR322 derivative harboring the malE31 gene under the control of its natural promoter (Betton et al. 1996).

Maltose transport

Maltose transport activity in whole cells and in proteoliposome (see below) was estimated by measuring the uptake of [14C] maltose in a filtration assay. Cells harboring pTrc99 derivatives were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (0.1 mg/mL), harvested at A600 = 0.6 (≈3.108 cells/mL), and washed twice in minimal M63 medium containing chloramphenicol (0.1 mg/mL). A mixture of [14C] maltose (653 mCi/mmole) at 0.2 μCi/mL and unlabeled maltose (final concentration 2 μM) was added to 1 mL of cell suspension. At the indicated time intervals, aliquots (150 μL) were quickly filtered through membrane filters (HAWP 0.45 μm, Millipore). Filters were thoroughly washed with M63 medium, dried, and counted in a scintillation counter (LS 5000TD, Beckman Coulter). Each assay was run in triplicate.

Cell fractionation

Cells harboring pTrc99 derivatives were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (0.1 mg/mL), and harvested at A600 = 1.5. These cultures were fractionated by spheroplast preparation as described previously (Betton and Hofnung 1996). The cell pellets, normalized to the same A600, were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 M sucrose. Lysozyme (0.2 mg/mL) and EDTA (10 mM) were added, and the suspensions were incubated for 15 min at 4°C. The samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm, and the supernatants containing the periplasmic fractions were withdrawn. The spheroplast pellets were washed, freeze-thawed, sonicated, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants were discarded and the pellets were washed with Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.1% (v/v) Triton, and resuspended in Tris-HCl buffer to give the membrane fractions. The subcellular periplasmic and membrane fractions were mixed with SDS–polyacrylamide sample buffer, boiled, and analyzed on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by Coomassie blue staining. For quantitative analyses, gels were scanned with an ImageMaster VDS camera (Amersham Biosciences).

Reconstitution of the maltose transporter in proteoliposomes

Cultures of strain ED169 transformed with plasmids pAZFGQ and pACYC were grown at 30°C in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (0.1 mg/mL) and chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL) until A600 attained 0.8, and were then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 2 h. Membrane fractions, prepared as described previously, were treated with 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.2), containing 20% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1.1% octyl-β-glucoside, for 45 min on ice. Samples were then ultracentrifuged, and supernatants were reconstituted in proteoliposomes as described previously (Mourez et al. 1998). For transport assays, proteoliposome vesicles were mixed with MalE-wt, MalE31, or MalE211 at 3 μM (final concentration).

Protein purification

Strains MC4100 carrying pTrc99, and JMB5 carrying pTfkp, were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL ampicillin. Cells were harvested at A600 = 1.5 and resuspended in 100 mL of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Periplasmic proteins were released by osmotic shock according to Neu and Heppel (1965), and the shock fluid was applied onto a 30-mL Fast-Flow Q-Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.5). The column was washed with buffer A and proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–250 mM NaCl. Both wild-type and MalE31 proteins were purified further on a Sephacryl S-200HR (Amersham Biosciences) gel filtration column equilibrated in buffer A containing 0.15 M NaCl. For crystallographic studies, MalE31 was overproduced in PD28 transformed with p31H, renatured from inclusion bodies after a urea-solubilization step, and purified by affinity chromatography using a cross-linked amylose resin, as described previously (Betton and Hofnung 1996). Protein concentrations were determined from the absorbance at 280 nm with an extinction coefficient of ɛ = 68,750 M−1cm−1.

Fluorescence measurements

All fluorescence measurements were performed in 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) at 25°C. Protein samples (0.5 μM) were incubated with various maltose concentrations (ranging from 0.2 to 50 μM) before monitoring the fluorescence on a Fluoromax spectrofluorometer (Spex-Jobin Yvon). Excitation wavelength was 290 nm, and the emission intensities were recorded at 345 nm with a spectral bandwidth of 2 nm. The experimental data were analyzed with the following equation, using a nonlinear regression analysis program (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software):

|

(1) |

in which FP and FL represent the fluorescence intensities determined in absence and in presence, respectively, of various maltose concentrations, and P0 and L0 are the total protein and maltose concentrations, respectively, and KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant.

Crystallization and X-ray data collection

Crystals of MalE31 were grown by vapor diffusion using the hanging drop technique. A volume of 1 μL of protein was mixed with 1 μL of buffer containing 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5), 10% isopropanol, and 20% (w/v) PEG 4000. The final protein concentration was 3.5 mg/mL. The drop was sealed over a reservoir containing 1 mL of buffer and left at 17°C. Crystals appeared after 3 d as clusters of thin plates. A fragment of dimensions 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.06 mm3 was separated from a cluster and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after soaking briefly in a cryo-protecting buffer consisting of the crystallization buffer with 15% glycerol. Diffraction data were measured with a MarCCD detector at the beamline ID14-3, ESRF, Grenoble, with the crystal maintained at 100°K by an Oxford Cryostream system. The crystal-to-detector distance was 140 mm and the X-ray wavelength was 0.931 Å. A total of 363 images were recorded in rotation steps of 1° with an exposure time of 15 sec. per image. To minimize the effects of radiation damage, the crystal was translated in the beam halfway through the data collection so that a fresh region was exposed to the X-rays. Diffraction intensities were integrated and scaled with the program HKL (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). Unit cell parameters and data statistics are given in Table 1. Although the angle β of the unit cell was equal to 90°, within the limits of error, reducing the data in a primitive orthorhombic space group gave a high Rmerge (0.361), clearly indicating monoclinic symmetry.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data

| Crystal parameters | |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | |

| a | 42.04 |

| b | 89.12 |

| c | 95.98 |

| β | 90.0° |

| Z | 4 |

| Vm (Å3Da) | 2.2 |

| Data statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 26.0–1.85 (1.95–1.85) |

| Number of unique reflections | 60245 (8670) |

| R-merge | 0.058 (0.201) |

| ≤I>/σ | 9.2 (3.4) |

| Multiplicity | 7.5 (6.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.2) |

Structure determination

The structure was solved by molecular replacement with the program AMoRe (Navaza 1994) using the coordinates of wild-type MalE (Quiocho et al. 1997) as the search model (Protein Data Bank accession code 1anf). Molecular replacement calculations clearly indicated the presence of two independent molecules MalE31 in the asymmetric unit. The signal-to-noise ratio was 3.0 for each of the two highest peaks in the rotation function calculated with data in the resolution range 20.0–3.5 Å. These two solutions gave unambiguous peaks in the translation function. After referring the two independent molecules to a common crystallographic origin by a two-body translation search, they were refined as rigid bodies, giving an R-factor of 0.405 and a correlation coefficient of 0.552 for all data from 10.0 to 3.5 Å resolution. Although not included in the search model, the maltose ligand was clearly visible in the binding site of each protein molecule. The two molecules in the asymmetric unit are related by a noncrystallographic twofold screw axis essentially parallel to the [a] axis and intersecting the [b,c] plane at 0.50 and 0.22. The atomic model was refined with the program REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al. 1997) using all observed data between the resolution limits of 26.0–1.85 Å. Noncrystallographic symmetry restraints, bulk solvent corrections, and an anisotropic scale factor to the observed structure factors were applied; noncrystallographic symmetry restraints were removed for the final stages of the refinement. Manual adjustments were made to the model between cycles of refinement by reference to the electron density using the program O (Jones et al. 1991). The protein could be readily traced from the amino terminus to the penultimate carboxy-terminal residue, although weak density suggesting multiple conformations is seen for the peptide segment Tyr 99–Asn 100 in the second molecule. The final model, composed of 5788 atoms from the protein and maltose, and 813 solvent molecules, has R and Rfree values of 0.157 and 0.202 (5% of the data), respectively. The r.m.s.d. of bond lengths from ideal values is 0.013 Å. When superimposed upon each other, the two independent MalE31 molecules have a r.m.s.d. of 0.23 Å in main-chain atom positions (0.58 Å when side chains are included). The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession code 1lax).

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the memory of Maurice Hofnung, in whose laboratory this work was initiated. We thank the staff of ESRF (Grenoble) for providing facilities for crystallographic measurements. This work was supported by funds from Institut Pasteur and CNRS, and the Ministére de la Recherche (Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie, Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires, to J.-M.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0235103.

References

- Arie, J.-P., Sassoon, N., and Betton, J.-M. 2001. Chaperone function of FkpA, a heat shock prolyl isomerase, in the periplasm of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 39 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betton, J.-M. and Hofnung, M. 1996. Folding of a mutant maltose binding protein of E. coli which forms inclusion bodies. J. Biol. Chem. 271 8046–8052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betton, J.-M., Boscus, D., Missiakas, D., Raina, S., and Hofnung, M. 1996. Probing the structural role of an ab loop of maltose-binding protein by mutagenesis: Heat-shock induction by loop variants of the maltose-binding protein that form periplasmic inclusion bodies. J. Mol. Biol. 262 140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betton, J.-M., Sassoon, N., Hofnung, M., and Laurent, M. 1998. Degradation versus aggregation of misfolded maltose-binding protein in the periplasm of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 273 8897–8902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts, S. and King, J. 1999. There’s a right way and a wrong way: In vivo and in vitro folding, misfolding and subunit assembly of the P22 tailspike. Structure 7 R131–R139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos, W. and Shuman, H. 1998. Maltose/maltodextrin system of Escherichia coli: Transport, metabolism, and regulation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 204–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Sharma, S., Quiocho, F.A., and Davidson, A.L. 2001. Trapping the transition state of an ATP-binding cassette transporter: Evidence for a concerted mechanism of maltose transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 1525–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese, P.N. and Silhavy, T.J. 1998. Targeting and assembly of periplasmic and outer-membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32 59–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A.L., Shuman, H.A., and Nikaido, H. 1992. Mechanism of maltose transport in Escherichia coli: Transmembrane signaling by periplasmic binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89 2360–2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbouille, M., Shuman, H.A., Silhavy, T.J., and Schwartz, M. 1978. Dominant constitutive mutations in malT, the positive regulator gene of the maltose regulon in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 124 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X., Hall, J.A., Nikaido, H., and Quiocho, F.A. 2001. Crystal structures of the maltodextrin/maltose-binding protein complexed with reduced oligosaccharides: Flexibility of tertiary structure and ligand binding. J. Mol. Biol. 306 1115–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplay, P., Szmelcman, S., Bedouelle, H., and Hofnung, M. 1987. Silent and functional changes in the periplasmic maltose-binding protein of Escherichia coli K12. J. Mol. Biol. 194 663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase-Pettingell, C.A. and King, J. 1988. Formation of aggregates from thermolabile in-vivo folding intermediate in P22 tailspike maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 263 4977–4983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hor, L.I. and Shuman, H.A. 1993. Genetic analysis of periplasmic binding protein dependent transport in Escherichia coli. Each lobe of maltose-binding protein interacts with a different subunit of the MalFGK2 membrane transport complex. J. Mol. Biol. 233 659–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.A., Zou, J.Y., Cowan, S.W., and Kjeldgaard, M. 1991. Improved methods for binding protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinska, B., Fayet, O., Baird, L., and Georgopoulos, C. 1989. Identification, characterization, and mapping of the Escherichia coli htrA gene, whose product is essential for bacterial growth only at elevated temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 171 1574–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur, M.W. and Thornton, J.M. 1991. Influence of proline residues on protein conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 218 397–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas, D., Betton, J.-M., and Raina, S. 1996. New components of protein folding in extracytoplasmic compartments of Escherichia coli SurA, FkpA and Skp/OmpH. Mol. Microbiol. 21 871–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitraki, A., Fane, B., Haase-Pettingell, C., Sturtevant, J., and King, J. 1991. Global suppression of protein folding defects and inclusion body formation. Science 253 54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourez, M., Hofnung, M., and Dassa, E. 1997. Subunit interactions in ABC transporters: A conserved sequence in hydrophobic membrane proteins of periplasmic permeases defines an important site of interaction with the ATPase subunits. EMBO J. 16 3066–3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourez, M., Jehanno, M., Schneider, E., and Dassa, E. 1998. In vitro interaction between components of the inner membrane complex of the maltose ABC transporter of Escherichia coli: Modulation by ATP. Mol. Microbiol. 30 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov, G.N., Vagin, A.A., and Dodson, E.J. 1997. Refinement of molecular structures by the maximum likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D 53 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu, H.C. and Heppel, L.A. 1965. The release of enzymes from Escherichia coli by osmotic shock and during the formation of spheroplasts. J. Biol. Chem. 240 3685–3692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. and Minor, M. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiocho, F.A., Spurlino, J.C., and Rodseth, L.E. 1997. Extensive features of tight oligosaccharide binding revealed in high-resolution structures of the maltodextrin transport/chemosensory receptor. Structure 5 997–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffy, S., Sassoon, N., Hofnung, H., and Betton, J.-M. 1998. Tertiary structure-dependence of misfolding substitutions in loops of the maltose-binding protein. Protein Sci. 7 2136–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saul, F.A., Vulliez-le Normand, B., Lema, F., and Bentley, G.A. 1998. Crystal structure of a dominant B-cell epitope from the preS2 region of hepatitis B virus in the form of an inserted peptide segment in maltodextrin-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 280 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman, H.A. 1982. Active transport of maltose in Escherichia coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 257 5455–5461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurlino, J.C., Lu, G.Y., and Quiocho, F.A. 1991. The 2.3-Å resolution structure of the maltose-or maltodextrin-binding protein, a primary receptor of bacterial active transport and chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 266 5202–5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauch, K.L., Johnson, K., and Beckwith, J. 1989. Characterization of degP, a gene required for proteolysis in the cell envelope and essential for growth of Escherichia coli at high temperature. J. Bacteriol. 171 2689–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, S., Vassylyev, D.G., Matsushima, M., Kashiwagi, K., Igarashi, K., and Morikawa, K. 1996. Crystal structure of PotD, the primary receptor of the polyamine transport system in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271 9519–9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treptow, N.A. and Shuman, H.A. 1985. Genetic evidence for substrate and periplasmic-binding-protein recognition by the MalF and MalG proteins, cytoplasmic membrane components of the Escherichia coli maltose transport system. J. Bacteriol. 163 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treptow, N.A. and Shuman, H.A. 1988. Allele-specific malE mutations that restore interactions between maltose-binding protein and the inner-membrane components of the maltose transport system. J. Mol. Biol. 202 809–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]