Abstract

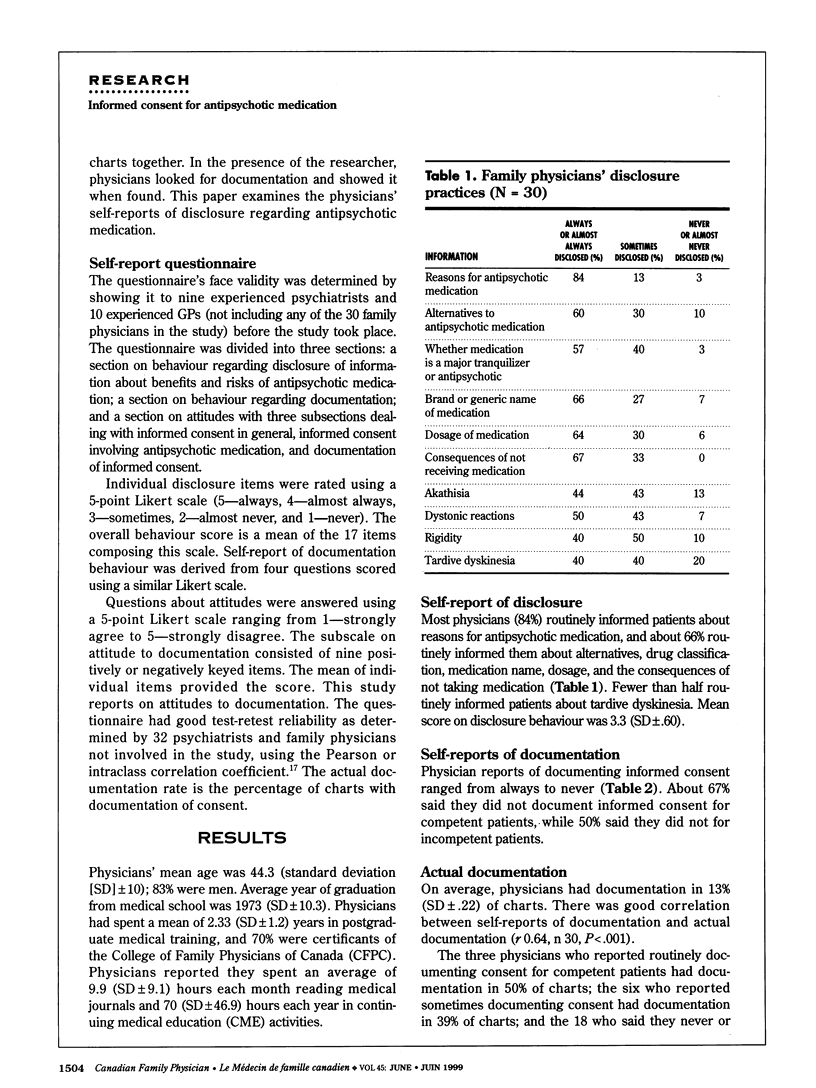

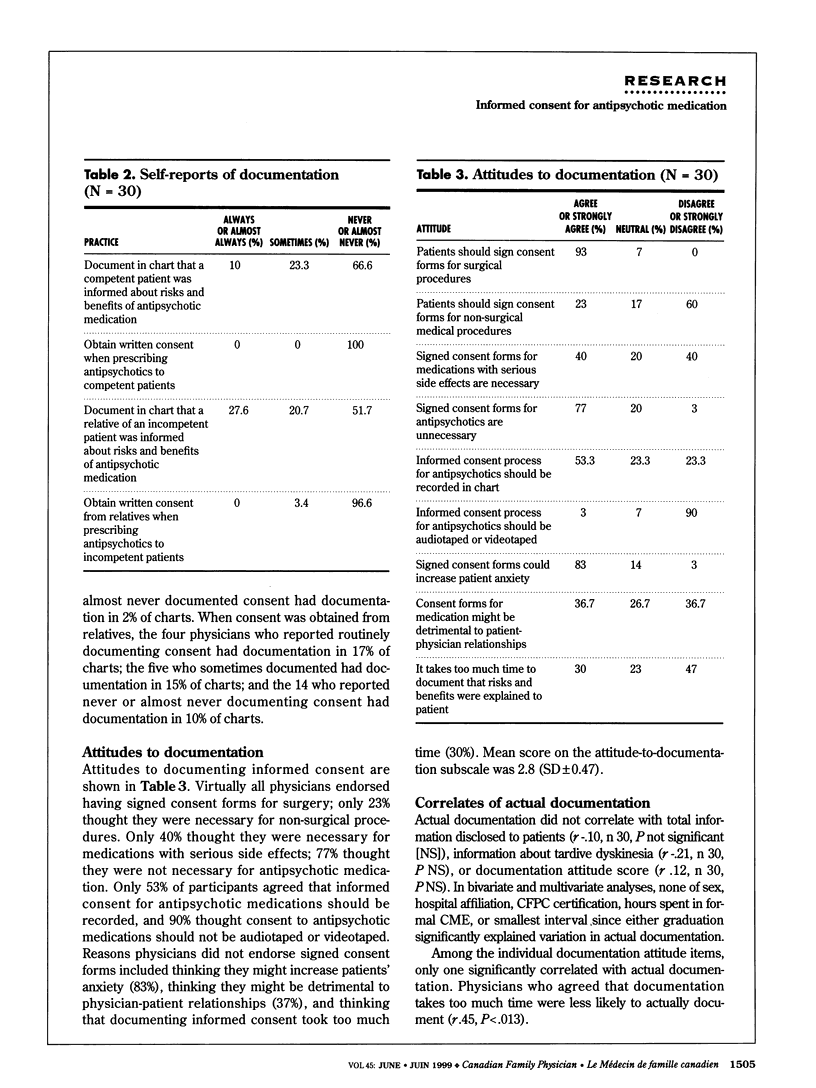

OBJECTIVE: To determine family physicians' attitudes and practices regarding documentation of informed consent for antipsychotic medication. DESIGN: Pilot cross-sectional study. SETTING: Teaching and non-teaching hospitals in Toronto, Ont. PARTICIPANTS: Thirty family physicians were selected in equal numbers from teaching and non-teaching hospitals with no more than five physicians from a given hospital. Participants were treating at least 10 patients with antipsychotic medication. Participants' mean age was 44.3 years; 83% were men. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Documentation of consent and of disclosure of consent for antipsychotic medication in patients' charts. RESULTS: Documentation was found in only 13% of charts. Whether it was there or not did not correlate with information disclosed, score on an attitude scale, or demographics. Physicians who found documentation time-consuming were less likely to document. Most physicians disclosed reasons for antipsychotic medication, but less than half described tardive dyskinesia, a potentially irreversible movement disorder that affects about 25% of patients on long-term treatment. CONCLUSIONS: The low rate of documentation observed in this sample was consistent with reports of similar samples and might indicate that family physicians are unaware of recommendations for documentation or simply do not have time to keep abreast of current recommendations. Many physicians thought signed consent forms unnecessary for psychotic patients, and even more believed seeking consent for antipsychotic medications would increase patient anxiety.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersson C., Chakos M., Mailman R., Lieberman J. Emerging roles for novel antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998 Mar;21(1):151–179. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin S., Munetz M. R. CMHC practices related to tardive dyskinesia screening and informed consent for neuroleptic drugs. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994 Apr;45(4):343–346. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgiel A. E., Williams J. I., Bass M. J., Dunn E. V., Evensen M. K., Lamont C. T., MacDonald P. J., McCoy J. M., Spasoff R. A. Quality of care in family practice: does residency training make a difference? CMAJ. 1989 May 1;140(9):1035–1043. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. A., Thomson M. A., Oxman A. D., Haynes R. B. Evidence for the effectiveness of CME. A review of 50 randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1992 Sep 2;268(9):1111–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn E. V., Bass M. J., Williams J. I., Borgiel A. E., MacDonald P., Spasoff R. A. Study of relation of continuing medical education to quality of family physicians' care. J Med Educ. 1988 Oct;63(10):775–784. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J. M., Smith J. M. Tardive dyskinesia: prevalence and risk factors, 1959 to 1979. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982 Apr;39(4):473–481. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290040069010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy N. J., Sanborn J. S. Disclosure of tardive dyskinesia: effect of written policy on risk disclosure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1992;28(1):93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman I., Schachter D., Jeffries J., Goldhamer P. Informed consent and tardive dyskinesia. Long-term follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996 Sep;184(9):517–522. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley R. G., Paul W. M., Morrison G. H., Beckett R. F., Goldsmith C. H. Five-year results of the peer assessment program of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. CMAJ. 1990 Dec 1;143(11):1193–1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munetz M. R., Peterson G. A. Documenting informed consent for treatment with neuroleptics: an alternative to the consent form. Psychiatr Serv. 1996 Mar;47(3):302–303. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter D., Kleinman I. Psychiatrists' documentation of informed consent. Can J Psychiatry. 1998 Dec;43(10):1012–1017. doi: 10.1177/070674379804301006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sovner R., Dimascio A., Berkowitz D., Randolph P. Tardive dyskinesia and informed consent. Psychosomatics. 1978 Mar;19(3):172-3, 176-7. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(78)71009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K. M., Kelner M. Informed consent: the physicians' perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24(2):135–143. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein R. M. Legal aspects of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders. Leg Med. 1985:117–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]