The avian infectious bronchitis virus main protease has been crystallized; crystals diffract to 2.7 Å resolution.

Keywords: infectious bronchitis virus, main protease

Abstract

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is the prototype of the genus Coronavirus. It causes a highly contagious disease which affects the respiratory, reproductive, neurological and renal systems of chickens, resulting great economic losses in the poultry industry worldwide. The coronavirus (CoV) main protease (Mpro), which plays a pivotal role in viral gene expression and replication through a highly complex cascade involving the proteolytic processing of replicase polyproteins, is an attractive target for antiviral drug design. In this study, IBV Mpro was overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography have been obtained using microseeding techniques and belong to space group P6122. X-ray diffraction data were collected in-house to 2.7 Å resolution from a single crystal. The unit-cell parameters were a = b = 119.1, c = 270.7 Å, α = β = 90, γ = 120°. Three molecules were predicted to be present in the asymmetric unit from a calculated self-rotation function.

1. Introduction

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is the prototype of the genus Coronavirus (Spaan & Cavanagh, 2004 ▶; Lai & Holmes, 2001 ▶), the members of which can infect humans and multiple species of animals, causing a variety of highly prevalent and severe diseases (Spaan & Cavanagh, 2004 ▶; Ziebuhr, 2005 ▶; Pereira, 1989 ▶; Lai & Holmes, 2001 ▶). For instance, a previously unknown human coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), the emergence of which was most likely to have been the result of animal–human transmission (Lau et al., 2005 ▶; Li et al., 2005 ▶), was identified as the aetiological agent of a global outbreak of a life-threatening form of pneumonia called severe acute respiratory syndrome (Peiris et al., 2003 ▶; Kuiken et al., 2003 ▶; Ksiazek et al., 2003 ▶; Drosten et al., 2003 ▶). From their genome sequences, coronaviruses can be classified into three distinct groups (Spaan & Cavanagh, 2004 ▶). IBV belongs to group III (Lai & Holmes, 2001 ▶), which only infects avian species, and leads to a highly contagious disease affecting the respiratory, reproductive, neurological and renal systems of chickens, resulting in a drop in egg production in adult birds and damaging the developing reproductive system in young birds. IBV infection predisposes chickens to infection with secondary pathogens. The incidence of IBV-related nephritis can result in high mortality rates (Siddell et al., 2005 ▶; Cavanagh, 2005 ▶; Ignjatovic & Sapats, 2000 ▶). IBV infection is prevalent in all countries with an intensive poultry industry, with the incidence of infection approaching 100% in most locations, causing great economic loss worldwide (Ignjatovic & Sapats, 2000 ▶). At the present time, control of IBV relies almost exclusively on vaccination and management (Holmes, 2001 ▶; Siddell et al., 2005 ▶). However, there are two major problems associated with the use of vaccines. Firstly, there are many serotypes of IBV; secondly, there is at least circumstantial evidence to suggest that new serotypes may emerge by recombination, possibly involving the live vaccine virus itself (Lee & Jackwood, 2000 ▶; Cavanagh, 2003 ▶).

The coronavirus main protease (Mpro) is a chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease (Anand et al., 2002 ▶; Yang et al., 2003 ▶). It not only processes at its own flanking sites within the replicase polyproteins involved in viral RNA synthesis, but also directs the processing of all downstream domains of the replicase polyproteins via at least 11 conserved cleavage sites, mediating coronavirus replication and transcription (Anand et al., 2005 ▶; Ziebuhr et al., 2000 ▶; Ziebuhr, 2005 ▶). The functional importance and the absence of cellular homologues identifies it as an attractive target for anti-coronavrius drug design (Yang et al., 2005 ▶; Anand et al., 2005 ▶). To date, several crystal structures of coronavirus Mpros have been reported for group I and II coronaviruses, which mostly infect mammals (Anand et al., 2002 ▶, 2003 ▶; Yang et al., 2003 ▶). However, there are no structures available for group III coronaviruses, which are distinct from those belonging to groups I and II. In this report, we describe the crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of IBV Mpro as a prelude to the elucidation of its three-dimensional structure in order to provide a basis for rational drug design.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The cDNA encoding IBV Mpro (M41 strain) was a gift from Professor Ming Liao (South China Agricultural University, People’s Republic of China). The gene sequence encoding the IBV Mpro was amplified using the PCR method with forward primer 5′-CGGGATCCTCTGGTTTTAAGAAA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCATTGTAATCTAACACC-3′ and then inserted into the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pGEX-4T-1 plasmid (Pharmacia, New York, USA). The resulting plasmid was then used to transform Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The sequence of the insert was verified by dideoxynucleotide sequencing. The positive clones harbouring the recombinant plasmid were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 at 310 K with shaking in 1 l LB medium containing 0.1 mg ml−1 ampicillin. The GST-fusion protein, GST-IBV Mpro, was then expressed by introducing 0.5 mM IPTG and incubating at 289 K for 10 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.3, 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl) and sonicated at 277 K. The cell lysate was centrifuged, the supernatant was collected and the fusion protein was purified by GST-glutathione affinity chromatography. The GST tag of the fusion protein was cleaved with GST-rhinovirus 3C protease. The recombinant IBV Mpro was further purified using anion-exchange chromatography. The purified and concentrated IBV Mpro (25 mg ml−1) was stored in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT for crystallization.

2.2. Crystallization

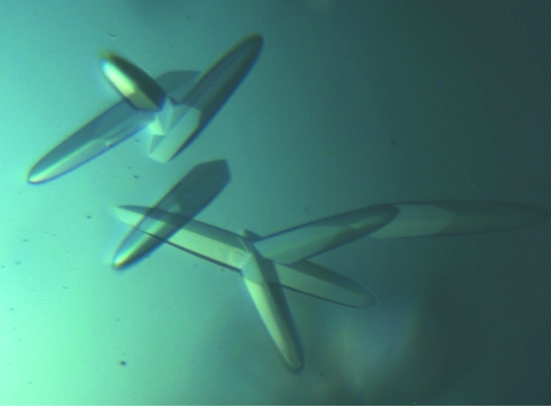

The purified protein was concentrated to 25 mg ml−1 using a 5K Filtron ultrafiltration membrane. Protein concentrations were determined by absorbance at 280 nm. Hampton Research Crystal Screen kits were used to screen crystallization conditions and positive hits were then optimized. Each drop was formed by mixing equal volumes (1.5 µl) of protein solution and reservoir solution and was allowed to equilibrate via vapour diffusion over 400 µl reservoir solution at 291 K. After one month, we obtained a cluster of small crystals. Some small crystals were transferred into a microcentrifuge tube containing 20 µl stabilizing solution including 5% PEG 4000, 12% 2-propanol, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate pH 6.5. The crystals were then crushed with a 3 mm diameter PTFE bead by vortexing (20 × 1 s cycles on a Vortex mixer) and 180 µl of stabilizing solution was added to the suspension, making up the seed stock. The seeds in the seed stock were then transferred using a fine whisker to new drops that had been pre-equilibrated for 4–5 d. One week later, several single crystals appeared in the drops (Fig. 1 ▶).

Figure 1.

Typical crystals of IBV Mpro grown by the hanging-drop method in 2.5% PEG 4000, 12% 2-propanol, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate pH 6.5. Typical crystal dimensions are 0.3 × 0.06 × 0.05 mm.

2.3. Data collection and processing

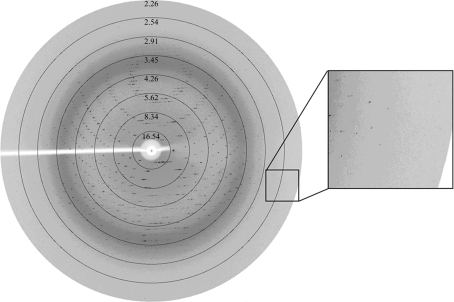

Diffraction data were collected at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF, Institute of High Energy Physics, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) at a wavelength of ∼1.0 Å with a MAR 345 (MAR Research, Hamburg) image-plate detector at 100 K. The crystal was mounted on a nylon loop and flash-cooled in a cold nitrogen-gas stream at 100 K using an Oxford Cryosystems cryostream. The cryoprotectant solution contained 20% glycerol, 2% PEG 4000, 9.6% 2-propanol, 0.08 M sodium cacodylate pH 6.5. A total of 120 frames of data were collected with an oscillation angle of 0.6° and an exposure time of 180 s for each image (Fig. 2 ▶). All intensity data were indexed, integrated and scaled with the HKL-2000 programs DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

Figure 2.

A typical X-ray diffraction pattern from a crystal of IBV Mpro. The diffraction image was collected on a MAR Research image-plate detector. An enlarged image is shown on the right.

3. Results and discussion

Initial microcrystals were obtained from condition No. 41 of Crystal Screen I (Hampton Research) containing 20% PEG 4000, 10% 2-propanol, 0.1 M Na HEPES pH 7.5. Optimization of the conditions yielded the best crystals from a solution containing 2.5% PEG 4000, 12% 2-propanol, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate pH 6.5, but the crystals were found to be unsuitable for X-ray diffraction. Crystal growth was further optimized by the microseeding technique and IBV Mpro crystals subsequently diffracted to 2.7 Å resolution. The crystals belong to space group P6122, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 119.1, c = 270.7 Å, α = β = 90, γ = 120° (see Table 1 ▶). From 357 356 observed reflections, 31 778 independent reflections were selected according to the criterion for observed reflections [I/σ(I) > 0]. Assuming the presence of three molecules in the asymmetric unit predicted from a self-rotation function calculated using CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶), the solvent content is estimated to be 55% and the Matthews coefficient (V M; Matthews, 1968 ▶) 2.7 Å3 Da−1. Selected data statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. The structural and functional analysis of IBV Mpro will be published elsewhere.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Space group | P6122 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 119.1, b = 119.1, c = 270.7, α = 90, β = 90, γ = 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | ∼1.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–2.7 |

| Observed reflections | 357356 |

| Unique reflections | 31778 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (98.8) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 21.8 (5.1) |

| Rmerge† (%) | 10.8 (41.8) |

R

merge =

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean of the observations Ii(hkl) of reflection hkl.

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean of the observations Ii(hkl) of reflection hkl.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Zihe Rao for generous support and Xiaoyu Xue, Qi Zhao and Haitao Yang for technical assistance. This work was supported by Project 973 of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant No. 2006CB806503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 30221003), the Sino–German Center [grant No. GZ236(202/9)], the Sino–European Project on SARS Diagnostics and Antivirals (SEPSDA) of the European Commission (grant No. 003831), the Innovation Team Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (grant No. 5200638) and the Knowledge Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant No. KSCX1-YW-R-05).

References

- Anand, K., Palm, G. J., Mesters, J. R., Siddell, S. G., Ziebuhr, J. & Hilgenfeld, R. (2002). EMBO J.21, 3213–3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, K., Yang, H., Bartlam, M., Rao, Z. & Hilgenfeld, R. (2005). Coronaviruses with Special Emphasis on First Insights Concerning SARS, edited by A. Schmidt, M. H. Wolff & O. Weber, pp. 173–199. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag.

- Anand, K., Ziebuhr, J., Wadhwani, P., Mesters, J. R. & Hilgenfeld, R. (2003). Science, 300, 1763–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, D. (2003). Avian Pathol.32, 567–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, D. (2005). Avian Pathol.34, 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763. [Google Scholar]

- Drosten, C. et al. (2003). N. Engl. J. Med.348, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, K. V. (2001). Fields Virology, edited by D. M. Knipe & P. M. Howley, pp. 1187–1203. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Ignjatovic, J. & Sapats, S. (2000). Rev. Sci. Tech.19, 493–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek, T. G. et al. (2003). N. Engl. J. Med.348, 1953–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiken, T. et al. (2003). Lancet, 362, 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M. M. C. & Holmes, K. V. (2001). Fields Virology, edited by D. M. Knipe & P. M. Howley, pp. 1163–1179. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Lau, S. K. P., Woo, P. C. Y., Li, K. S. M., Huang, Y., Tsoi, H.-W., Wong, B. H. L., Wong, S. S. Y., Leung, S.-Y., Chan, K.-H. & Yuen, K.-Y. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 14040–14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. W. & Jackwood, M. W. (2000). Arch. Virol.145, 2135–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Shi, Z., Yu, M., Ren, W., Smith, C., Epstein, J. H., Wang, H., Crameri, G., Hu, Z., Zhang, H., Zhang, J., McEachern, J., Field, H., Daszak, P., Eaton, B. T., Zhang, S. & Wang, L.-F. (2005). Science, 309, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol.33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Eznymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Peiris, J. S., Lai, S. T., Poon, L. L., Guan, Y., Yam, L. Y., Lim, W., Nicholls, J., Yee, W. K., Yan, W. W., Cheung, M. T., Cheng, V. C., Chan, K. H., Tsang, D. N., Yung, R. W., Ng, T. K. & Yuen, K. Y. (2003). Lancet, 361, 1319–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, H. G. (1989). Andrewes’ Viruses of Vertebrates, edited by J. S. Porterfield, pp. 42–57. London: Baillière Tindall.

- Siddell, S. G., Ziebuhr, J. & Snijder, E. J. (2005). Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbia Infections: Virology, 10th ed., edited by B. W. J. Mahy & V. ter Meulen, pp. 823–856. London: Hodder Arnold.

- Spaan, W. J. M. & Cavanagh, D. (2004). Virus Taxonomy. VIIIth Report of the ICTV, pp. 945–962. London: Elsevier/Academic Press.

- Yang, H., Xie, W., Xue, X., Yang, K., Ma, J., Liang, W., Zhao, Q., Zhou, Z., Pei, D., Ziebuhr, J., Hilgenfeld, R., Yuen, K. Y., Wong, L., Gao, G., Chen, S., Chen, Z., Ma, D., Bartlam, M. & Rao, Z. (2005). PLoS Biol.3, e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H., Yang, M., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Lou, Z., Zhou, Z., Sun, L., Mo, L., Ye, S., Pang, H., Gao, G. F., Anand, K., Bartlam, M., Hilgenfeld, R. & Rao, Z. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 13190–13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr, J. (2005). Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol.287, 57–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr, J., Snijder, E. J. & Gorbalenya, A. E. (2000). J. Gen. Virol.81, 853–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]