Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We present a case of a foramen magnum meningioma that highlights the importance of the neurologic exam when evaluating a patient with dysphagia. A 58-year-old woman presented with an 18-month history of progressive dysphagia, chronic cough and 30-pound weight loss. Prior gastroenterologic and laryngologic workup was unrevealing.

Results

Her neurologic examination revealed an absent gag reflex, decreased sensation to light touch on bilateral distal extremities, hyperreflexia, and tandem gait instability. Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy was normal, whereas laryngoscopy and video fluoroscopy revealed marked hypopharyngeal dysfunction. Brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a 3.1 × 2.7 × 2.9 cm foramen magnum mass consistent with meningioma. The patient underwent neurosurgical resection of her mass with near complete resolution of her neurologic symptoms. Pathology confirmed diagnosis of a WHO grade I meningothelial meningioma.

Conclusion

CNS pathology is an uncommon but impressive cause of dysphagia. Our case demonstrates the importance of a thorough neurologic survey when evaluating such a patient.

KEY WORDS: dysphagia, meningioma, foramen magnum

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas are extra-axial central nervous system (CNS) tumors that arise from the arachnoid cells of the dura mater. They have an annual incidence of six per 100,000 people, most commonly presenting during the fifth and sixth decades of life and only rarely in childhood.1–3 The vast majority of meningiomas are benign, slow growing tumors that occur more frequently in people of African descent and in women. The 2:1 female/male ratio observed for intracranial meningiomas is consistent with the increased incidence of meningiomas in post-menopausal women treated with exogenous hormone replacement.3–5

Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the most common methods used to diagnose meningiomas. MRI scans are the preferred modality with its increased resolution, absence of bone artifact, and intense tumor contrast enhancement.2,6,7 Depending on the tumor site, the patient’s operative risk and the associated neurologic symptomatology, surgical resection of the tumor may be performed and is most often curative.8,9. For poor surgical candidates and incompletely resected, recurrent or aggressive tumors, radiotherapy is a consideration.9–11

We report the unusual case of a woman with a foramen magnum meningioma presenting with dysphagia and cough. Cognitive and somatic motor and sensory deficits were minimal.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A 58-year-old African-American woman presented to us with an 18-month history of progressive dysphagia and productive cough. At the time of presentation, she could no longer tolerate her oral secretions. Within several seconds of attempting to swallow, she experienced globus and bouts of involuntary coughing resulting in regurgitation of ingested contents. Her reduced dietary intake resulted in a reported 30-pound weight loss over a period of 2 months. Before presenting at our institution, she had an extensive workup in France where esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD), laryngoscopies, and bronchoscopies were performed. These tests were non-diagnostic. Two barium swallow evaluations were attempted but aborted because of aspiration. She was diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma, but pharmacotherapy with proton pump inhibitors and bronchodilators did not relieve her symptoms.

Although no objective sensory deficits were noted, the patient reported diffuse pain along the right side of her face and neck, and numbness and tingling in her fingers and toes bilaterally. Cranial nerve exam demonstrated an absent gag reflex bilaterally, but was otherwise normal. Evaluation of muscle strength revealed no focal or diffuse abnormalities. Brachioradialis, patellar and Achilles deep tendon reflexes were globally 3+, brisk, and symmetric. A primitive jaw jerk reflex, four beats of bilateral ankle clonus, and equivocal Babinski signs were observed. Her cerebellar exam was normal except for tandem gait instability. Her head, neck, lung, cardiac, and abdominal exams were normal.

Given the patient’s neurologic findings, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain was ordered. A repeat EGD was performed secondary to her progressive symptoms and proved to be normal. A chest x-ray demonstrated retained barium in the lungs, but was otherwise normal (not shown). Videofluoroscopic swallow evaluation confirmed aspiration and found marked hypopharyngeal dysfunction with decreased epiglottic retroflexion and aryepiglottic fold closure. Upper esophageal motility was normal. Decreased arytenoid sensation, post-cricoid edema and significant pyriform sinus pooling of secretions were demonstrated by flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy.

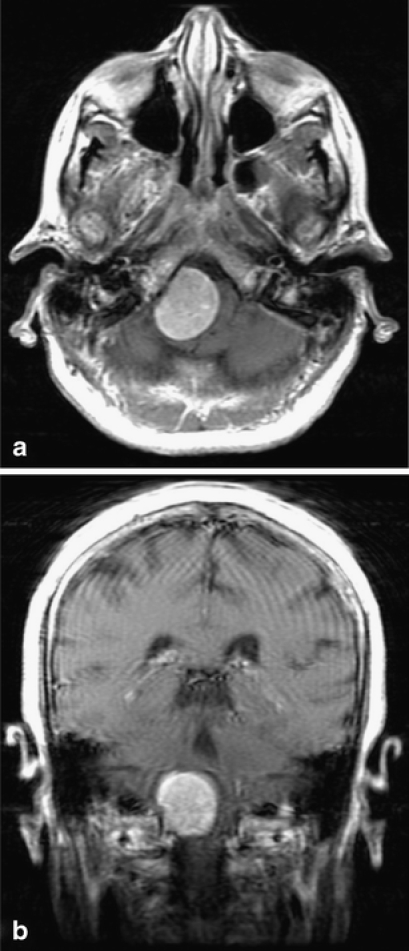

The MRI scan was performed and revealed a large dural-based mass measuring 3.1 × 2.7 × 2.9 cm in the foramen magnum at the right cranio-cervical junction (Fig. 1). The mass was homogeneously contrast enhancing and T1 iso-dense, suspicious for meningioma. There was significant compression and leftward displacement of the medulla. A second small 6-mm dural-based enhancing lesion, also suspicious for meningioma, was found along the right falx cerebri.

Figure 1.

Neuroradiology findings. (a) Axonal and (b) coronal sections. Gadolinium-enhanced T1W1 demonstrates large extra-axial mass at right foramen magnum resulting in significant displacement of the medulla.

Neurosurgical resection was performed using a right lateral transcondylar approach with C1 and partial C2 laminectomy. Pathological evaluation of the surgical specimen confirmed a World Health Organization (WHO) Grade I meningothelial meningioma.1

The patient experienced symptomatic recovery beginning with immediate resolution of fingertip paresthesias and unhindered swallowing on postoperative day two. She tolerated full meals without difficulties before uneventful discharge to her home on postoperative day 5. Eight days after surgery, her neurological exam had normalized with only mild numbness over her right fourth toe, slight rightward deviation on tongue protrusion and a reduced gag reflex bilaterally.

DISCUSSION

The initial evaluation of dysphagia requires a basic understanding of swallow physiology. Swallowing is a complex process that can be divided into three distinct phases: oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal. The oral phase requires proper mastication and salivary production to form an appropriate bolus for subsequent stages of swallowing and digestion.12,13 The pharyngeal phase involves neuromuscular coordination for distal advancement of the bolus, protection of the airway, and normal relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES).13,14 The esophageal phase begins just distal to the UES and requires proper peristaltic propulsion of the bolus combined with appropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.13,15 Disruption of any of these three phases can result in dysphagia.

The differential diagnosis of dysphagia is extremely broad. It is useful to separate diagnoses of dysphagia into two primary categories, oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and both of these can be further divided into neuromuscular and structural etiologies. Neuromuscular disease resulting in oropharyngeal dysphagia is characterized by discoordinated swallowing secondary to strokes, degenerative neurologic diseases, peripheral neuropathies, or other intrinsic muscular abnormalities.13,16 Structural lesions resulting in oropharyngeal dysphagia include neoplasms, webs, and diverticulum.13 Likewise, esophageal dysphagia can also be grouped into neuromuscular disorders such as achalsia, spastic motor disease, and scleroderma, or structural lesions such as neoplasms, strictures, webs, and foreign bodies.15–17 A more complete differential diagnosis of dysphagia can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differential Diagnosis of Dysphagia

| Oropharyngeal dysphagia | Esophageal dysphagia |

|---|---|

| Neuromuscular Disease | Neuromuscular Disease |

| Neuropathic Diseases | Achalasia |

| Stoke | Scleroderma |

| Brain stem tumors | Diffuse esophageal spasm |

| Amyotreophic lateral sclerosis | Nutcracker esophagus |

| Multiple sclerosis | Non-specific spastic esophageal motility disorders |

| Hungtington’s disease | Paraneoplastic syndromes |

| Parkinson’s Disease | Chagas disease |

| Dementia | Vagal nerve injury |

| Poliomyelitis | Idiopathic hypomotility |

| Tabes dorsalis | Connective tissue disease |

| Diabetes melittus | Diabetes Mellitus |

| Recurrent laryngealnerve injury | Hypothyroidism |

| Paraneoplastic syndromes | |

| Diptheria | |

| Rabies | Structural lesions |

| Lead poisioning | Peptic stricture |

| Reflux esophagitis | |

| Myopathic Diseases | Esophageal carcinoma |

| Inflammatory myopathies | Benign esophageal tumor |

| Polymyositis | Esophageal web |

| Dermatomyositis | Corrosive damage |

| Scleroderma | Post-surgical change |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | Diverticula |

| Muscular dystrophies | Foreign body |

| Myasthenia gravis | Post-radiation change |

| Hyperthyroidism | Scleroderma |

| Cricopharyngeal achalasia | Amyloidosis |

| Vascular anomalies | |

| Structural lesions | Vertebral osteophytes |

| Oropharyngeal carcinoma | Mediastinal masses |

| Benign esophageal tumor | |

| Inflammatory disease | |

| Diverticulum | |

| Esophageal webs | |

| Cervical spondylosis | |

| Anterior mediastinal masses | |

| Cervical spondylosis | |

| Corrosive damage | |

| Post-surgical change | |

| Foreign body | |

| Post-radiation changes |

Source: Yamada T, ed. Textbook of Gastroenterology, 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003 (Modified)

A careful history is essential to the initial evaluation of a dysphagic patient. Patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia tend to complain of difficulty initiating a swallow or symptoms immediately upon swallow initiation. It is often accompanied by coughing, choking, and possible aspiration. When asked to localize their symptoms, patients generally point to the cervical region.13,18–20 In contrast, patients with esophageal dysphagia experience symptoms several seconds after initiating a swallow that commonly localize to the suprasternal or retrosternal area.19–21

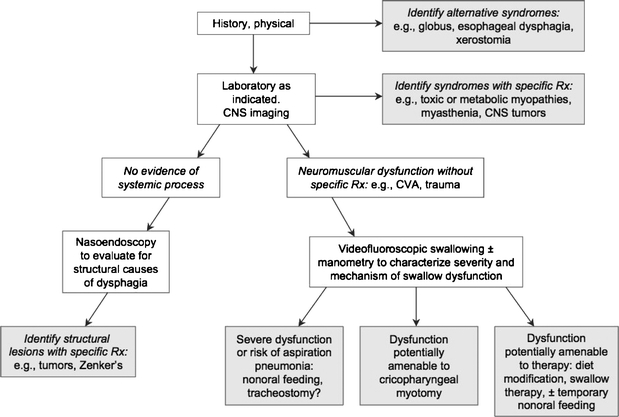

Helpful diagnostic procedures in a patient with dysphagia include flexible laryngoscopy, barium esophagram, and gastroesophageal endoscopy. Flexible laryngoscopy is particularly useful for the evaluation of a patient complaining of oropharyngeal dysphagia, easily identifying any masses, lesions, or hypopharyngeal pooling of secretions or food.22,23 A barium study is relatively inexpensive with few complications and can assess esophageal motility as well as obstruction.24 Any masses or lesions identified by barium study should be evaluated and possibly biopsied by gastroesophageal endoscopy. Additional studies such as esophageal manometry, videofluoroscopy, pH monitoring, or additional imaging studies may be necessary for diagnosis.13,23,25 The American Gastroenterological Association’s official recommendations regarding the management of oropharyngeal dysphagia are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Clinical approach and key objectives in the management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The objective is to reach a shaded box, which equates to a specific management strategy. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology 1999; 116:452–454 (Modified).

Our patient’s subtle neurologic findings prompted us to broaden our differential diagnosis to include central nervous processes. Pending an MRI scan, additional studies such as a swallow study and flexible laryngoscopy were found to be abnormal, although nondiagnostic, increasing our clinical suspicion of a neurologic process. Neurogenic dysphagia most commonly occurs secondary to stroke,26 but may also be caused by brain stem lesions, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and other degenerative conditions (Table 1). Our patient’s MRI revealed a large mass at the foramen magnum consistent with a meningioma.

Meningiomas represent approximately 20% of all intracranial tumors, the most common non-glial primary intracranial tumor.1–3 An estimated 1–2% of the population has incidental asymptomatic meningiomas, and in autopsy studies 8% of these are multiple.1 Although there are several histological classification systems for meningiomas, the most commonly used is that of the WHO. Benign meningiomas are classified as WHO Grade I, and account for 90% of cases, whereas atypical (Grade II) and anaplastic (Grade III) meningiomas account for 6% and 2% of cases respectively.10,27 Although the prognosis of a patient with a benign meningioma is excellent, atypical and anaplastic meningiomas show increased recurrence rates.28 Metastasis occurs in approximately one quarter of anaplastic meningiomas and survival of patients with anaplastic meningioma is significantly lower than that of the atypical variant at both 5 (64% vs 95%) and 10 years (35% vs 79%).29,30

This case demonstrates not only an unusual cause of dysphagia, but also an uncommon anatomic location for a meningioma. Meningiomas most often occur at the convexities and basal regions of the cerebrum; only 1.4–3.2% of meningiomas arise at the foramen magnum.31,32 Because of an unusual constellation of symptoms and neurologic signs, foramen magnum tumors are often identified only after they have attained a large size.6,32–34 In a study of 40 cases of foramen magnum meningiomas, the most common early symptoms were posterior headache followed by paresthesias and motor deficits. The most common symptoms at diagnosis were motor (50%) and sensory defects (42%) in the extremities. Thirty percent of patients presented with some form of ninth and tenth nerve impairment.33 The anatomic proximity of a foramen magnum mass to the cerebellar tonsils, caudal medulla, lower cranial nerves, rostral spinal cord, and upper cervical nerves results in highly variable symptomatology that is commonly misdiagnosed.6,32 The varied clinical presentation may lead to the initial diagnoses of multiple sclerosis, carpal tunnel syndrome, syringomyelia, and cervical spondylosis, which may delay appropriate therapy.33 Whereas the most common symptoms are somatic sensory and motor dysfunction, bulbar dysfunction, including dysphagia and dysarthria caused by lower cranial nerve impairment, is known to be associated with foramen magnum meningiomas31–33.

We present an unusual case of dysphagia caused by a large meningioma at the foramen magnum. Our report demonstrates the need to consider neuromuscular etiologies and pursue neuroimaging studies when patients present with dysphagia and focal neurologic signs and symptoms. In this case, thorough history and physical examination with subsequent imaging allowed for definitive therapy with full resumption of the patient’s normal daily activities.

Acknowledgments

G. Tsao was supported by a Stanford Medical Scientist Fellowship grant and a Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship grant. This case was presented as a poster at the SGIM California Regional Meeting, San Francisco, CA, in March 2007.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Kleihues P, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, et al. The WHO classification of tumors of the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002;61(3):215–25; discussion 26–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, Collie D. Meningiomas. Lancet 2004;363(9420):1535–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Longstreth WT, Jr., Dennis LK, McGuire VM, Drangsholt MT, Koepsell TD. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Cancer 1993;72(3):639–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Jhawar BS, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Cardiovascular risk factors for physician-diagnosed lumbar disc herniation. Spine J 2006;6(6):684–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Muccioli G, Ghe C, Faccani G, Lanotte M, Forni M, Ciccarelli E. Prolactin receptors in human meningiomas: characterization and biological role. J Endocrinol 1997;153(3):365–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Boulton MR, Cusimano MD. Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications, and nuances. Neurosurg Focus 2003;14(6):e10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Goldsmith B, McDermott MW. Meningioma. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2006;17(2):111–20, vi. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chamberlain MC. Intracerebral Meningiomas. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2004;6(4):297–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Modha A, Gutin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: a review. Neurosurgery 2005;57(3):538–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wilson CB. Meningiomas: genetics, malignancy, and the role of radiation in induction and treatment. The Richard C. Schneider Lecture. J Neurosurg 1994;81(5):666–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Goldsmith BJ, Wara WM, Wilson CB, Larson DA. Postoperative irradiation for subtotally resected meningiomas. A retrospective analysis of 140 patients treated from 1967 to 1990. J Neurosurg 1994;80(2):195–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mishellany A, Woda A, Labas R, Peyron MA. The challenge of mastication: preparing a bolus suitable for deglutition. Dysphagia 2006;21(2):87–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ. AGA technical review on management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology 1999;116(2):455–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Altschuler SM. Laryngeal and respiratory protective reflexes. Am J Med 2001;111 Suppl 8A:90S–4S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Dogan I, Mittal RK. Esophageal motor disorders: recent advances. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2006;22(4):417–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Yamada T. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

- 17.Meyer GW, Castell DO. Evaluation and management of diseases of the esophagus. Am J Otolaryngol 1981;2(4):336–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Castell DO, Donner MW. Evaluation of dysphagia: a careful history is crucial. Dysphagia 1987;2(2):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Spieker MR. Evaluating dysphagia. Am Fam Phys 2000;61(12):3639–48. [PubMed]

- 20.Hendrix TR. Art and science of history taking in the patient with difficulty swallowing. Dysphagia 1993;8(2):69–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Trate DM, Parkman HP, Fisher RS. Dysphagia. Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Prim Care 1996;23(3):417–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Adang RP, Vismans JF, Talmon JL, Hasman A, Ambergen AW, Stockbrugger RW. Appropriateness of indications for diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: association with relevant endoscopic disease. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;42(5):390–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Quine MA, Bell GD, McCloy RF, Devlin HB, Hopkins A. Appropriate use of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy-a prospective audit. Steering Group of the Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Audit Committee. Gut 1994;35(9):1209–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Ott DJ. Radiographic techniques and efficacy in evaluating esophageal dysphagia. Dysphagia 1990;5(4):192–203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Hewson EG, Ott DJ, Dalton CB, Chen YM, Wu WC, Richter JE. Manometry and radiology. Complementary studies in the assessment of esophageal motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1990;98(3):626–32. [PubMed]

- 26.Kidd D, Lawson J, Nesbitt R, MacMahon J. Aspiration in acute stroke: a clinical study with videofluoroscopy. Q J Med 1993;86(12):825–9. [PubMed]

- 27.Bondy M, Ligon BL. Epidemiology and etiology of intracranial meningiomas: a review. J Neurooncol 1996;29(3):197–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Perry A, Stafford SL, Scheithauer BW, Suman VJ, Lohse CM. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21(12):1455–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Palma L, Celli P, Franco C, Cervoni L, Cantore G. Long-term prognosis for atypical and malignant meningiomas: a study of 71 surgical cases. J Neurosurg 1997;86(5):793–800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Stafford SL, Lohse CM, Wollan PC. “Malignancy” in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer 1999;85(9):2046–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Arnautovic KI, Al-Mefty O, Husain M. Ventral foramen magnum meninigiomas. J Neurosurg 2000;92(1 Suppl):71–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Marin Sanabria EA, Ehara K, Tamaki N. Surgical experience with skull base approaches for foramen magnum meningioma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2002;42(11):472–8; discussion 9–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.George B, Lot G, Boissonnet H. Meningioma of the foramen magnum: a series of 40 cases. Surg Neurol 1997;47(4):371–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Meyer FB, Ebersold MJ, Reese DF. Benign tumors of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg 1984;61(1):136–42. [DOI] [PubMed]