Abstract

Rationale: Nuclear factor (NF)-κB is a prominent proinflammatory transcription factor that plays a critical role in allergic airway disease. Previous studies demonstrated that inhibition of NF-κB in airway epithelium causes attenuation of allergic inflammation.

Objectives: We sought to determine if selective activation of NF-κB within the airway epithelium in the absence of other agonists is sufficient to cause allergic airway disease.

Methods: A transgenic mouse expressing a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible, constitutively active (CA) version of inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase-β (IKKβ) under transcriptional control of the rat CC10 promoter, was generated.

Measurements and Main Results: After administration of Dox, expression of the CA-IKKβ transgene induced the nuclear translocation of RelA in airway epithelium. IKKβ-triggered activation of NF-κB led to an increased content of neutrophils and lymphocytes, and concomitant production of proinflammatory mediators, responses that were not observed in transgenic mice not receiving Dox, or in transgene-negative littermate control animals fed Dox. Unexpectedly, expression of the IKKβ transgene in airway epithelium was sufficient to cause airway hyperresponsiveness and smooth muscle thickening in absence of an antigen sensitization and challenge regimen, the presence of eosinophils, or the induction of mucus metaplasia.

Conclusions: These findings demonstrate that selective activation NF-κB in airway epithelium is sufficient to induce airway hyperresponsiveness and smooth muscle thickening, which are both critical features of allergic airway disease.

Keywords: airway epithelium, nuclear factor-κB, inhibitory κB kinase-β, airway hyperresponsiveness, smooth muscle cell

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation contributes to allergic airway disease, but it is not known whether activation of NF-κB in absence of other stimuli is sufficient to cause allergic airway disease.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study shows that NF-κB activation in airways is sufficient to trigger certain parameters of allergic disease and highlights the potential clinical benefit on focused targeting of the NF-κB pathway within the airways.

Allergic airway disease is characterized by eosinophilic inflammation and airway remodeling, which can induce mucus metaplasia, alterations in smooth muscle and blood vessel compartments, extracellular matrix deposition, and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) to inhaled bronchoconstricting agonists. The airway epithelium has also been suggested to play a causal role in initiating inflammation after exposure to antigen.

One critical regulator of inflammatory and immune processes is the transcription factor, nuclear factor (NF)-κB. NF-κB plays a causal role in the secretion of proinflammatory mediators from pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to various insults (1–3). NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm through binding to inhibitor of κB protein (IκB) α. Phosphorylation of IκBα on serines 32 and 36 by the IκB kinase (IKK) signalsome leads to the ubiquitination and degradation IκBα, leading to the nuclear localization NF-κB, and enhanced transcriptional activation of NF-κB–controlled target genes (4). IKK exists as a complex consisting of three proteins: IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ. IKKα and IKKβ contain enzymatic activity, whereas IKKγ is a regulatory component of the signalsome that regulates protein–protein interactions. In the canonical pathway of NF-κB activation, which is activated by a wide array of stimuli, such as TNF-α, T-cell receptors, and Toll-like receptors, IKKβ induces phosphorylation of IκBα, leading to transcriptional regulation of NF-κB target genes controlled by RelA/p50 dimeric complexes (4).

NF-κB has been widely implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma, and evidence for activation of NF-κB in bronchiolar epithelium is present in animal models of allergic airways disease (5), as well as in patients with asthma (6, 7). Furthermore, mice deficient in the NF-κB family member, c-Rel, or p50, have decreased pulmonary inflammation and AHR in a model of allergic airway disease (8–10). Through the use of transgenic mice and conditional ablation strategies, we and others recently demonstrated that activation of NF-κB within airway epithelium is necessary to induce airway inflammation after sensitization and challenge with ovalbumin (OVA) (11, 12). Although the aforementioned studies demonstrate that activation of NF-κB plays a causal role in allergic disease in mice, they did not address whether activation of NF-κB within airway epithelium is sufficient to drive allergic airway disease independent of other stimuli. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to create a transgenic mouse model in which activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway within the airway epithelial compartment is inducibly regulated, in order to determine its contribution to features of allergic airway disease. Transgenic mice in which a constitutively active (CA) version of IKKβ (CA-IKKβ) is expressed under the control of the CC10 promoter and the tetracycline operon (TetOP) were generated in order to activate the canonical NF-κB pathway within airway epithelium in response to administration of doxycycline (Dox). Some of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (13).

METHODS

Detailed descriptions of all procedures are available in the online supplement.

Generation of CC10-Tetracycline–inducible CA-IKKβ–Transgenic Mouse

Two independent lines (33 and 50) of bitransgenic mice expressing CC10-M2-hGHpA, and TetOP–CA-IKKβ constructs were generated in order to induce expression of CA-IKKβ in bronchiolar epithelium after administration of Dox. Mice were backcrossed for at least five generations into C57BL/6J mice, and transgene-negative (wild-type [WT]) littermates were used as control animals. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Vermont gave approval for all studies.

Culture of Primary Mouse Tracheal Epithelial Cells

Primary mouse tracheal epithelial (MTE) cells were isolated from CA-IKKβ–positive mice and littermate control animals, as described elsewhere (14). MTE cells were evaluated under submerged culture conditions.

Analysis of Transgene Expression

RNA from whole lung was extracted and reverse transcribed and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for CA-IKKβ cDNA expression performed with the forward primer used in genomic analysis and an hGHpA intron-spanning reverse primer, GAGCAGGCCAAAAGCCAGGA.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was immediately collected, and cell counts evaluated, as described previously (11, 15).

Histological and Immunofluorescence Analysis

After killing and BAL, lungs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for the generation of paraffin sections and hematoxylin and eosin staining to evaluate histopathology (15). For evaluation of nuclear localization of RelA, frozen lung sections were prepared, or MTE cells were fixed, stained (15), and analyzed by confocal microscopy. To evaluate smooth muscle changes, sections were stained with an α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Three images of large airways and three images of small bronchioles of similar dimension were obtained from each mouse, from four mice per treatment group. Images were blinded and ranked at a scale from 1 to 4: 1, no or minimal reactivity; 2, minimal to modest thickening; 3, moderate thickening; and 4, severe thickening. Images were scored by four independent investigators that were blinded to the study.

Analysis of NF-κB–driven Inflammatory Genes

cDNA was synthesized from MTE cells or pulverized lung tissue and expression of keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, and CCL20 mRNAs were quantified by real-time TaqMan PCR. Cytokine levels in the BAL fluid or cell culture media were assessed by a 23-cytokine Bioplex assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Model of Allergic Airway Disease

Allergic airway inflammation was induced as previously reported (5). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 40 μg of OVA plus Alum on Days 1 and 7. WT or CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice were given Dox starting on Day 7 and continuing until being killed. Mice were subjected to aerosolized 1% OVA in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes on Days 14–16, and killed 2 days after the final OVA challenge.

Respiratory Mechanics and Determination of AHR

Anesthetized mice were mechanically ventilated for assessment of respiratory mechanics using the forced oscillation technique as previously described (16, 17) (flexiVent; SCIREQ, Inc., Montreal, PQ, Canada).

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were repeated at least once. Data are presented as mean value (±SEM), and were subjected to analysis of variance or Student's t test, where appropriate. Analyses with resultant P < 0.05 were determined significant, except where noted.

RESULTS

Characterization of Dox-inducible CC10-CA-IKKβ–Transgenic Mice

To examine whether activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway in airway epithelium is sufficient to induce features associated with allergic airway disease, bitransgenic mice were generated in which CA-IKKβ, SS171/181EE, was expressed under the control of the TetOP, and expression was targeted to nonciliated airway epithelial cells using the rat CC10 promoter to express the tetracycline transactivator-M2 (11, 18, 19). Two lines of CC10-Tet–inducible CA-IKKβ (CA-IKKβ) mice (33, 50) were further characterized. Both lines had similar levels of TetOP-CAIKKβ and CC10-r–tetracycline transactivator transgene integration, as determined by slot blot analysis (data not shown). To determine inducibility of the CA-IKKβ transgene, mice were fed Dox-containing chow and cDNA was synthesized from whole lung RNA. Through the use of an hGH pA-intron–spanning reverse primer, we differentiated between genomic and mRNA expression of CA-IKKβ. As shown in Figure 1A, administration of Dox for 7 days induced CA-IKKβ mRNA in transgene-positive animals. In the absence of Dox, no detectable CA-IKKβ mRNA was apparent within the lung. To ensure that the transgene was being induced specifically in the lung, cDNA was generated from lung, heart, thymus, liver, spleen, kidney, and uterus from a transgene-positive mouse administered Dox for 1 week. As demonstrated in Figure 1A (lower panel), mRNA expression of CA-IKKβ was only detected in the lung. These data demonstrate that Dox induced expression of CA-IKKβ mRNA using the tet-on (tetracycline-responsive) expression system, and that the expression of the transgene was specific to the lung. Furthermore, expression of the CA-IKKβ resulted in marked increases in content of IKKβ protein in lung homogenates, whereas no IKKβ protein was detected in CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice that did not receive Dox or in the other control groups, because levels of endogenous IKKβ were below the level of detection (Figure 1B, upper panel, and data not shown). Serine 536 of RelA is a direct target of phosphorylation by IKKβ and is required for transactivation of NF-κB–dependent genes (20). We therefore assessed phosphorylation of RelA at serine 536, the target of IKKβ in lung homogenates. Results in Figure 1B (lower panel) demonstrate increases in levels of phosphorylated RelA in CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice that received Dox, whereas no clear differences were apparent in any of the other groups. Nuclear localization of the transcriptionally active NF-κB subunit, RelA, is a hallmark of activation of the canonical pathway. To determine if induction of CC10–CA-IKKβ led to NF-κB nuclear localization in airway epithelium, transgene-negative WT littermate control mice and CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice received Dox for 3 days and RelA nuclear localization was determined by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. As seen in Figure 1C, CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox displayed marked RelA nuclear localization, predominantly in the airway epithelium, whereas no nuclear translocation of RelA was observed in CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice not receiving Dox, or in WT mice that received Dox.

Figure 1.

Constitutively active (CA) inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) β transgene expression in airway epithelium is inducible after doxycycline (Dox) administration. (A) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of CA-IKKβ cDNA induction: cDNA was generated from wild-type (WT) and CA-IKKβ mice from two independent lines given Dox for 7 days, and transgene expression was assessed by PCR. β-Actin mRNA levels were evaluated as a loading control; (lower panel) cDNA was generated from the heart, thymus, kidney, spleen, liver, and uterus of a CA-IKKβ mouse receiving Dox for 1 week, and CA-IKKβ expression was determined by PCR. Irrelevant lanes were cut from the gel. (B) Evaluation of IKKβ and serine 536 phosphorylated RelA (P536 RelA) levels in lung homogenates from control or CA-IKKβ mice in the presence or absence of Dox feeding for 1 week. Two independent samples from WT or CA-IKKβ groups (without Dox) were evaluated, whereas four independent samples from WT or CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox were processed. Gels were run and reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. Note that the lack of detection of endogenous IKKβ in the control groups is due to the short exposure time that is necessitated to visualize IKKβ in the CA-IKKβ–expressing mice. (C) Lung sections from WT and CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox for 3 days or fed regular chow were assessed for immunolocalization of RelA using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Nuclei were visualized with Sytox (green) and RelA was visualized using a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red). Nuclear localization is indicated by overlap of fluorophores, resulting in a yellow color. Original magnification, ×200; inset: enlargement of bronchiolar epithelial region.

To verify expression of the CA-IKKβ transgene specifically in proximal airway epithelium, primary tracheal epithelial cell cultures were established from CA-IKKβ mice or WT littermates, because the CC10 promoter is expressed in tracheal epithelial cells (21). In response to in vitro treatment with Dox, CA-IKKβ mRNA expression increased in MTE (Figure 2A). In comparison with WT cells, nuclear presence of RelA was already apparent in MTE cultures derived from CA-IKKβ mice, in the absence of Dox, although Dox administration led to additional increases of nuclear RelA (Figure 2B). Evaluation of NF-κB–dependent cytokines in the culture medium of MTE cells derived from CA-IKKβ or WT mice demonstrated that marked increases in IL-3, IL-6, granulocyte colony–stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor, and regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) occurred in CA-IKKβ–transgenic cells. As seen in Table 1, increases in levels of these cytokines in CA-IKKβ cells compared with WT cells occurred in the absence of Dox, which only effectuated marginal additional increases. These data are consistent with the observed expression of IKKβ (Figure 2A) and nuclear RelA (Figure 2B) under these conditions, and indicate apparent leakiness of the Tet-on system in the culture model, or presence of Dox derivatives in the cell culture medium.

Figure 2.

Primary tracheal epithelial cells isolated from CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice demonstrate induction of the CA-IKKβ transgene, nuclear factor (NF)-κB nuclear localization, and production of proinflammatory cytokines. (A) cDNA was generated from primary tracheal epithelial cell cultures from CA-IKKβ and wild-type (WT) mice. Cultures were treated with 10 μg/ml of doxycycline (Dox) and harvested at 1, 2, 4, 24, and 48 hours. Transgene expression was assessed as described in Figure 1. (B) Primary epithelial cell cultures from WT and CC10–CA-IKKβ mice were treated with 10 μg/ml of Dox for 24 hours and RelA nuclear localization was determined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Nuclei were visualized with Sytox (green) and RelA was visualized using a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red). Nuclear localization is indicated by overlap of fluorophores, resulting in a yellow color. Original magnification, ×200.

TABLE 1.

PRIMARY EPITHELIAL CELLS FROM WILD-TYPE AND CONSTITUTIVELY ACTIVE IκB KINASE β MICE EXPOSED IN VITRO TO 10 μg/ml OF DOXYCYCLINE FOR 24 HOURS, OR LEFT UNTREATED, AND LEVELS OF CYTOKINES IN MEDIUM ASSESSED BY BIOPLEX ANALYSIS

| Cytokine | WT (pg/ml) | WT Dox (pg/ml) | CA-IKKβ (pg/ml) | CA-IKKβ Dox (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF | 891.7 ± 105.3 | 823.8 ± 86.3 | 1,260.4 ± 205.6* | 1,465.8 ± 182.7* |

| GM-CSF | 1,511.9 ± 593.5 | 1,586.9 ± 427.0 | 3,113.8 ± 450.9* | 3,395.3 ± 350.9* |

| IL-1α | 54.9 ± 3.1 | 49.5 ± 5.3 | 73.9 ± 8.7* | 82.0 ± 5.9* |

| IL-3 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 13.8 ± 1.8* | 13.3 ± 1.5* |

| IL-6 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | 10.3 ± 1.6* | 10.2 ± 1.2* |

| RANTES | 274.8 ± 114.5 | 325.3 ± 132.3 | 548.1 ± 87.1* | 637.7 ± 45.8* |

Definition of abbreviations: CA = constitutively active; Dox = doxycycline; G-CSF = granulocyte colony–stimulating factor; GM-CSF = granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor; IKKβ = IκB kinase β; RANTES = regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted; WT = wild type.

Levels of eotaxin, IFN-γ, IL-1β, -2, -4, -9, -10, -12p40, -12p70, -13, and -17, KC, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and -1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α were not different between any of the experimental groups (data not shown). Values presented are means ± SEM.

Significance (P < 0.05) when compared to wild-type mice.

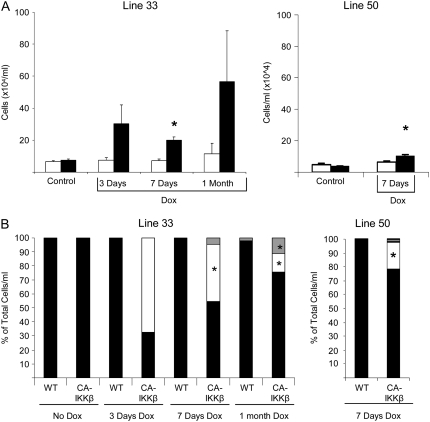

CA-IKKβ Transgene Expression Is Sufficient to Cause Airway Inflammation

We next addressed the impact of selective activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway in airway epithelial cells in the inflammatory process. CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox for 3 days, 7 days, or 1 month exhibited increases in total cell counts recovered from BAL fluid (Figure 3A) as compared with WT littermates receiving Dox, or CA-IKKβ mice not receiving Dox. Differential cell counts revealed that transgene activation led to increases in macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in CA-IKKβ mice (Figure 3B). Levels of neutrophils were highest after 3 days of Dox, whereas lymphocyte levels were highest after 1 month. No eosinophils were observed in BAL fluid at any of the time points evaluated (Figure 2C). The observed inflammatory responses were greater in transgene line 33 compared with line 50 (Figures 3A and 3B) Evaluation of lung histopathology revealed peribronchiolar inflammation in both lines of CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice that received Dox, in association with apparent thickening of the bronchiolar epithelium (Figure 3C), whereas no overt histological changes were apparent in CA-IKKβ mice not fed Dox or in WT littermate control animals receiving Dox.

Figure 3.

CA-IKKβ transgene induction results in pulmonary inflammation. Cell counts (A) and differentials (B) from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of wild-type (WT) or CA-IKKβ mice were assessed after administration of doxycycline (Dox) for 3 days, 7 days, or 1 month. Lines 33 and 50 represent transgenic mice obtained from two independent founders. Data in (A) are presented as mean (±SEM); open bars, WT; solid bars, CA-IKKβ. (B) Gray bars, lymphocytes; open bars, neutrophils; closed bars, macrophages. On average, three mice were included per group per time point, with the exception of the group of CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice receiving Dox, which contained seven mice/group/time point. (C) Representative hematoxylin–eosin sections from transgene-negative littermates and two lines of CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox for 7 days. Original magnification, ×200; insets, ×400.

Expression of NF-κB–driven proinflammatory genes in lung tissue was evaluated by performing real-time PCR analysis on cDNA generated from lung homogenates. Figure 4 demonstrates that the mRNA levels of MIP-2 and KC, which are important in neutrophil recruitment, and CCL20, a dendritic cell and T cell chemoattractant, were significantly increased in lung tissue of CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox. Increases in levels of KC and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor were also detectable in BAL fluid from CA-IKKβ mice in response to administration of Dox (Table 2). Note that Dox administration to WT mice, or lack of Dox administration to CA-IKKβ mice, did not result in increased expression or production of proinflammatory mediators. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that Dox-dependent expression of the CA-IKKβ transgene construct in airway epithelium leads to NF-κB activation, expression of NF-κB–dependent proinflammatory mediators, and an inflammatory process characterized by macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.

Figure 4.

CA-IKKβ activation leads to the increased expression of proinflammatory genes. cDNA was prepared from lung homogenates from wild-type (WT) and CA-IKKβ mice given doxycycline (Dox) for 7 days or 1 month for assessment of mRNA expression of inflammatory genes by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. On average, three mice were included per group per time point, with the exception of the group of CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice receiving Dox, which contained seven mice/group per time point.

TABLE 2.

CYTOKINE LEVELS IN BRONCHOALVEOLAR LAVAGE FLUID FROM TRANSGENE-NEGATIVE (WILD-TYPE) OR CONSTITUTIVELY ACTIVE IκB KINASE β MICE AFTER 1 WEEK OF DOXYCYCLINE ADMINISTRATION

| WT | WT Dox | CA-IKKβ | CA-IKKβ Dox | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | (pg/ml) | (pg/ml) | (pg/ml) | (pg/ml) |

| G-CSF | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 48.4 ± 23.7* |

| GM-CSF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 78.8 ± 26.3* |

| IL-12 (p40) | 33.5 ± 5.9 | 38.1 ± 7.3 | 38.7 ± 3.8 | 119.8 ± 24.5* |

| KC | 19.8 ± 3.1 | 16.2 ± 2.6 | 26.1 ± 4.0 | 64.8 ± 15.0* |

| MCP-1 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 14.2 ± 3.9 | 4.2 ± 2.0 | 27.9 ± 6.5* |

| RANTES | 6.0 ± 3.1 | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 9.4 ± 1.4 | 45.5 ± 16.0* |

Definition of abbreviations: CA = constitutively active; Dox = doxycycline; G-CSF = granulocyte colony–stimulating factor; GM-CSF = granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor; IKKβ = IκB kinase β; KC = keratinocyte-derived chemokine; MCP = monocyte chemoattractant protein; RANTES = regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted; WT = wild type.

Cytokines were assessed by Bioplex analysis. IFN-γ, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1a, IL-2, -3, and -4 were nondetectable, and eotaxin, IL-10, -12p70, -13, -17, -1α, -1β, -5, -6, and -9, MIP-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α were not different between any of the experimental groups (data not shown). Values presented are means ± SEM.

Significance (P < 0.05) when compared to wild-type and CA-IKKβ mice not receiving Dox.

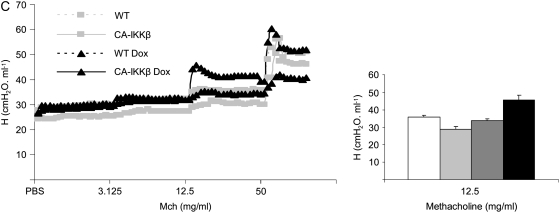

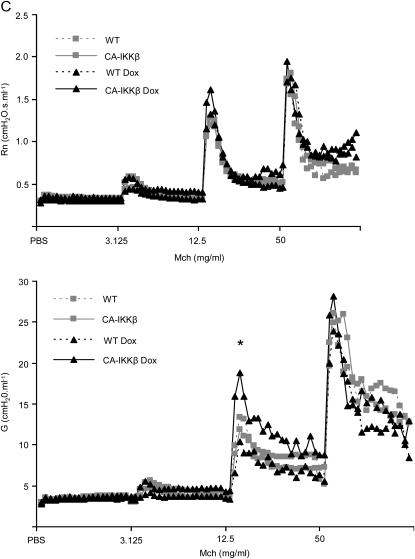

CA-IKKβ Transgene Expression Leads to AHR

We addressed the impact of NF-κB activation in airway epithelium on AHR, a cardinal feature of allergic airways disease. CA-IKKβ mice were given Dox for 1 week before the assessment of various parameters of airway mechanics at baseline or after ascending doses of inhaled methacholine (Mch) (16). Results in Figure 5 demonstrate that CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice that received Dox for 1 week displayed no differences in baseline (PBS) mechanics when evaluating Newtonian resistance (Rn), airflow heterogeneity/tissue elastance (G), or airway closure/elastance (H) in comparison with WT mice that received Dox, or CA-IKKβ mice not administered Dox. However, after induction of the CA-IKKβ transgene for 1 week, increases in the parameters Rn and G were apparent at doses of 3.125 and 12.5 mg/ml of Mch in comparison with the control groups, whereas no differences were observed in H, indicating that hyperresponsiveness was localized to the central airways, consistent with the location of expression of the transgene and activation of NF-κB.

Figure 5.

CA-IKKβ transgene expression results in airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR). (A) Wild-type (WT) and CA-IKKβ mice were given doxycycline (Dox) for 7 days, after which AHR was measured using the forced oscillation technique, as described in Methods. Shown are respiratory mechanics for the parameters: (A) Rn, Newtonian resistance, a measure of airway resistance; (B) G, a measure of airflow heterogeneity or tissue elastance; and (C) H, airway closure/elastance. Individual tracings are shown after nebulization of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control in addition to ascending doses of methacholine (Mch). Right: mean group averages of parameters Rn, G, and H at the indicated dose of Mch. *P ⩽ 0.05, analysis of variance. Results represent data obtained from three mice/group from line 50. A separate experiment performed with CA-IKKβ mice from line 33 (three mice/group) revealed similar trends that were statistically significant (data not shown).

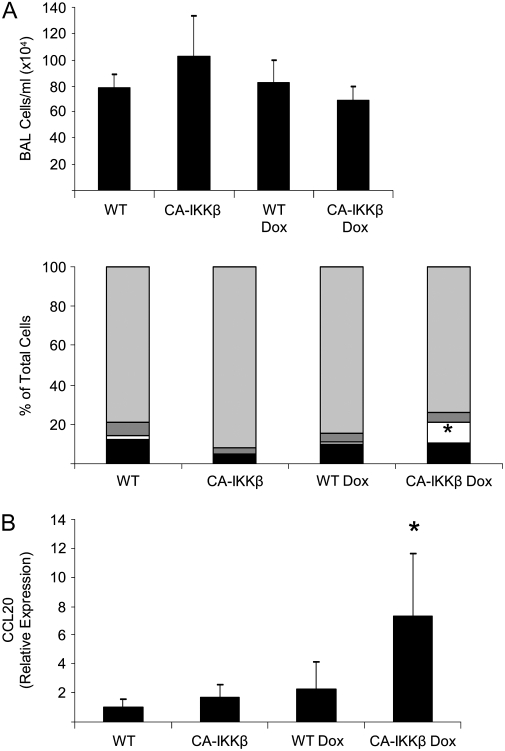

Airway Epithelial NF-κB Activation Enhances OVA-induced Allergic Airway Disease

A role for NF-κB in eliciting the inflammatory response to allergen challenge has been demonstrated in mice incapable of activating NF-κB in the epithelium of the proximal airways (11, 12). Therefore, we sought to determine the contribution of airway epithelial NF-κB to the development of allergic airways disease during challenge with OVA. CA-IKKβ and WT littermate control animals were immunized with OVA on Day 1 and, after the second OVA sensitization (Day 7), Dox was administered until harvest (Day 18). In mice subjected to OVA sensitization and challenge, total cell counts were not further increased in CA-IKKβ transgene–expressing mice (Figure 6A). However CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox displayed an increase in the proportion of neutrophils in BAL compared with WT mice (Figure 6A). Interestingly, CA-IKKβ mice receiving Dox demonstrated a marked enhancement in CCL20 mRNA expression in lung homogenates (Figure 6B) and an increase in proinflammatory and Th2 cytokines, KC, MIP-1β, and IL-17 in the BAL fluid as compared with their WT control littermates, or CA-IKKβ littermates that did not receive Dox (Table 3). Evaluation of respiratory mechanics demonstrated that CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice receiving Dox and subjected to OVA sensitization and challenge (OVA/OVA) displayed increases in the parameter, G, in response to Mch compared with the other experimental groups that also were subjected to OVA/OVA (Figure 6C). Parameters Rn and H were not different between the experimental groups subjected to OVA/OVA (data not shown), suggesting that CA-IKKβ expression enhanced AHR in mice with allergic airways disease by promoting narrowing of smaller airways, or by increasing tissue resistance (22).

Figure 6.

Enhancement of inflammatory mediators and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in CA-IKKβ mice (line 33) subjected to sensitization and challenge with ovalbumin (OVA). Wild-type (WT) or CA-IKKβ mice were immunized with OVA on Days 1 and 7. On Day 7, doxycycline (Dox) administration was started and continued until mice were killed on Day 18. All mice were subjected to aerosolized OVA on Days 14, 15, and 16. (A) Total cell counts and differentials from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of CA-IKKβ mice (CA-IKKβ, n = 7; CA-IKKβ Dox, n = 8; WT, n = 7; WT Dox, n = 8) subjected to immunization and challenge with OVA. *P ⩽ 0.05, ANOVA. Light gray bars, eosinophils; dark gray bars, lymphocytes; open bars, neutrophils; solid bars, macrophages. (B) Increased mRNA expression of CCL20 in lung homogenates. (C) Representative tracings for the variables Rn and G are shown after nebulization of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control in addition to ascending doses of methacholine (Mch).

TABLE 3.

INCREASED LEVELS OF PROINFLAMMATORY CYTOKINES IN THE BRONCHOALVEOLAR LAVAGE FLUID OF CONSTITUTIVELY ACTIVE IκB KINASE β MICE SUBJECTED TO SENSITIZATION AND CHALLENGE WITH OVALBUMIN

| WT | WT Dox | CA-IKKβ | CA-IKKβ Dox | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 5) | (n = 5) | (n = 7) | (n = 6) | |

| Cytokine | (pg/ml) | (pg/ml) | (pg/ml) | (pg/ml) |

| IL-17 | 47.2 ± 12.0 | 38.2 ± 7.5 | 35.3 ± 10.8 | 64.0 ± 12.8* |

| IL-4 | 185.9 ± 69.3 | 108.9 ± 28.0 | 127.2 ± 42 | 240.9 ± 52.0* |

| KC | 304.5 ± 28.3 | 336.3 ± 62.5 | 337.8 ± 43.3 | 847.2 ± 219.1* |

| MIP-1β | 53.5 ± 14.1 | 17.3 ± 4.4 | 42.9 ± 14.6 | 101.2 ± 23.9* |

Definition of abbreviations: CA = constitutively active; Dox = doxycycline; IKKβ = IκB kinase β; KC = keratinocyte-derived chemokine; MIP = macrophage inflammatory protein; WT = wild type.

P ⩽ 0.05, significance when compared with wild-type and CA-IKKβ mice not receiving Dox; analysis of variance.

Eotaxin, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-10, -12p40, -12p70, -13, -1α, -1β, -2, -3, -5, -6, and -9, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MIP-1α, RANTES, and tumor necrosis factor-α were not different between any of the experimental groups (data not shown). Values presented are means ± SEM.

Increased Response of CA-IKKβ Mice to Allergen Challenge Is Not Due to Mucus Metaplasia

Increased mucus production is considered to be a major cause of airflow obstruction in asthma, and mucus metaplasia is believed to contribute to AHR in mouse models of the disease. Therefore, we evaluated mucus metaplasia in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice. Results in Figure 7 demonstrate that no increases in mRNA expression of Muc5AC (Figure 7A) or CLCA3 (Figure 7B) occurred in lung homogenates of CA-IKKβ–expressing mice, consistent with the lack of periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reactivity in CA-IKKβ mice receiving Dox (Figure 7C). In contrast, CA-IKKβ–expressing mice subjected to sensitization and challenge with OVA displayed mucus metaplasia based upon PAS reactivity to a comparable extent as transgenic littermate control animals exposed to OVA. These findings suggest that the increases in AHR observed after expression of the CA-IKKβ transgene (Figures 5 and 6C) occurred independently of mucus metaplasia.

Figure 7.

CA-IKKβ expression has no effect on mucus metaplasia in naive or ovalbumin (OVA)-treated mice. (A) Assessment of MUC5AC and (B) CLCA3 gene expression in lung homogenates of CA-IKKβ mice that were fed doxycycline (Dox) for 1 week (line 33) (results were obtained from the after numbers of mice: CA-IKKβ, n = 6; CA-IKKβ Dox, n = 6; wild-type [WT], n = 3; WT Dox, n = 3). (C) Evaluation of periodic acid Schiff reactivity in lung tissue of CA-IKKβ that received Dox for 1 week or fed normal chow; OVA groups on the right represent WT or CA-IKKβ mice that received Dox and were immunized and challenged with OVA, as described in Figure 6. Original magnification, ×200.

Thickening of Airway Smooth Muscle in CA-IKKβ–Expressing Mice

Closer evaluation of parameters of AHR revealed that, in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice, the time to peak Mch responses occurred faster, and that parameters Rn and G remained elevated (Figure 5B), whereas, in other groups, these parameters returned to baseline. These patterns of responsiveness suggest potential alterations in smooth muscle in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice. We therefore evaluated airway smooth muscle (ASM) using an antibody directed against α-SMA. Results in Figure 8 demonstrate marked thickening of the smooth muscle layer, and the appearance of muscle bundles in CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice that received Dox, whereas no changes in smooth muscle were apparent in the control groups (Figure 8A). Blinded scoring of α-SMA immunoreactivity confirmed that thickening of the smooth muscle layer occurred in both the large airways as well as in small bronchioles (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

CA-IKKβ expression causes thickening of the airway smooth muscle (ASM) layer. Wild-type (WT) or CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice were kept in the absence or doxycycline (Dox) or fed Dox for 1 week, at which time mice were killed, and paraffin-embedded lung sections were prepared for evaluation of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) reactivity or staining with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathologic evaluation. Red reflects α-SMA reactivity. Slides were evaluated by light microscopy. Original magnification, ×200. (B) Quantification of ASM thickening in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice. Images were scored on a scale from 1 to 4 (1 representing the least reactivity, 4 representing the most α-SMA reactivity), according to the methodologies described in Methods section. Shown are mean scores (+SEM). * P < 0.05, analysis of variance.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of asthma is characterized by elevated levels of Th2 cytokines, eosinophilic inflammation, mucus metaplasia, and AHR. Recently, a role for airway epithelium in asthma pathogenesis has emerged, and epithelial cells are now considered an integral part of the innate immune system based upon their ability to sense and respond to a diverse array of inhaled stimuli with the activation of signaling pathways that control the production of oxidants, mucus, proinflammatory mediators, and proteins involved in airway remodeling (23). Previous studies that used transgenic or conditional ablation approaches to specifically inhibit NF-κB in airway or distal epithelium firmly established a causal role for this transcription factor in inflammatory responses to LPS or inhaled antigen (11, 12, 15, 24). Although inhibition of NF-κB in airway epithelium was sufficient to block the majority of the inflammatory response to antigen, antigen-induced AHR was not attenuated in this model, suggesting that NF-κB activation in airways may control only certain parameters of allergic airway disease (11). Moreover, the aforementioned studies corroborated the importance of NF-κB in the inflammatory process, but did not definitively discern whether NF-κB activation in these cells is sufficient to drive and promote allergic inflammation or AHR. To directly address this issue, we created transgenic mice wherein a CA-IKKβ was expressed in the airway epithelium, in a Dox-inducible manner, in order to activate the canonical pathway of NF-κB in the airway epithelium.

It is of relevance to highlight that Cheng and colleagues (25) recently created a transgenic mouse expressing the same CA-IKKβ construct in airway epithelium using almost identical strategies. Those investigators reported neutrophilic inflammation, pulmonary edema, and lung injury. Furthermore, chronic expression of the transgene led to mortality (25). Results from the present study confirm the increased production of proinflammatory mediators, such as MIP-2 and KC, and neutrophilic inflammation that were reported in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice (25). However, in contrast to the previous study, continued presence of Dox for 7 days and Dox feeding up to 1 month did not cause mortality in either line of CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice that we generated, suggesting that the levels of IKKβ transgene expression that are achieved with the Dox exposure regimen in our study were lower than those reported in the previous study. Alternatively, differences in outcomes may also be due to differences in genetic backgrounds of mice, or the strategies used to create the CA-IKKβ–expressing transgenic mice. An intriguing finding of the current study that was not reported previously is that CA-IKKβ expression was sufficient to cause increases in AHR in otherwise naive mice. The pattern of the mechanical response to Mch is reminiscent of the response observed in the AJ strain of mice, where AHR is related to increases in ASM cell contraction (26). CA-IKKβ–driven AHR occurred in the absence of marked elevations in Th2 cytokines, eosinophila, or mucus metaplasia. We identified here that CA-IKKβ expression in airways causes thickening of ASM. These results are of interest for a number of reasons. First, the transgene is expressed in mice in a C57BL\6 background, which is notably resistant to antigen-induced AHR compared with BALB/c mice, which are routinely used to measure antigen-induced AHR (27). It is therefore possible that CA-IKKβ–triggered AHR may be more robust when mice are backcrossed onto the BALB/c background, an endeavor that was beyond the scope of the present study.

Increases in AHR in naive CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice, or CA-IKKβ–transgenic mice subjected to OVA sensitization and challenge, occurred in association with a substantial presence of neutrophils (Figures 3 and 6), whereas we did not observe any eosinophils or changes in eosinophilia in response to antigen in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice. In general, eosinophils have been linked to AHR and remodeling (28), although some controversy exists regarding the exact roles of eosinophils in the disease process (29, 30). The role of the neutrophil in the pathogenesis of allergic airway disease remains enigmatic. Neutrophils are recovered in the BAL fluid of patients with severe asthma (31) and neutrophilic inflammation in experimental models has, in fact, been linked to AHR. For example, LPS administration, which triggers airway neutrophilia, also induces changes in respiratory mechanics and increases in AHR (32–34). Therefore, the marked presence of neutrophils might contribute to increases in AHR in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice. Neutrophils are capable of generating a number of mediators, such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, matrix metalloproteinases, and elastase, which have been linked to increases in AHR directly, or indirectly after stimulation of ASM cells or airway epithelial cells (35–38).

Mucus cell metaplasia is a feature of allergic airway disease that is considered to be a contributing component to airway obstruction and AHR (39, 40). As is demonstrated in Figure 7, CA-IKKβ–expressing mice did not express increased levels of MUC5AC or CLCA3 mRNA in lung tissue, nor did they display reactivity for PAS. This is in contrast to mice that were immunized and challenged with OVA, which revealed marked reactivity for those parameters. The lack of mucus metaplasia in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice is in line with the absence of marked increases in IL-13, the major Th2 cytokine that is linked to mucus metaplasia (41, 42). However, the lack of mucus metaplasia is surprising in light of previous studies demonstrating that neutrophil elastase induced mucin production and hypersecretion in human bronchial epithelial cells (37, 38) and caused mucus metaplasia in mouse lungs (43). It is plausible that mucus metaplasia occurs in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice beyond the timeframe of investigation within the current study, which may contribute to potentially chronic abnormalities in respiratory mechanics, although these possibilities remain to be formally tested.

Perhaps the most striking histopathologic change in lungs of CA-IKKβ–expressing mice is the thickening of the smooth muscle layer of large airways, which may be a contributing factor to the intrinsic increases in AHR observed in those mice. These new findings, which demonstrate a functional link between epithelial NF-κB activation to thickness of smooth muscle, are in contrast to a previous study demonstrating that conditional ablation of IKKβ in airway epithelium did not affect smooth muscle thickness in response to sensitization and challenge with OVA (12). This discrepancy may stem from the differences in experimental regimens, which used opposing strategies to evaluate the function of IKKβ. Furthermore, the OVA exposure regimen used in previous work might have resulted in production of mediators that masked the effect of epithelial NF-κB on smooth muscle thickness. An aberrant phenotype of ASM cells has been speculated to be sufficient to explain the pathology of asthma (44–46), and a role for smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia in asthma has been suggested (47). The current study did not investigate whether smooth muscle hypertrophy or proliferation occurred in CA-IKKβ–expressing mice, nor did we unravel whether the ASM exhibited an activated phenotype. Furthermore, the identity of mediators produced after CA-IKKβ expression within the airway epithelium, or intermediary structural or inflammatory cells that are responsible for thickening of the smooth muscle layer, remain to be determined.

In conclusion, we demonstrate here that activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway in airway epithelium is sufficient to drive airway inflammation, characterized by neutrophils and lymphocytes, thickening of the ASM layer, and AHR. Epithelial NF-κB activation also enhanced OVA-induced proinflammatory mediator production and AHR. Together, these findings demonstrate that activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway in airway epithelium, in the absence of other agonists, is sufficient to drive select features associated with human asthma. These findings further highlight the functional significance of changes in epithelial cell homeostasis or activation in chronic inflammatory lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Richard Gaynor (University of Texas) and Prabir Ray (University of Pittsburgh) for providing plasmid constructs, Dr. Mercedes R. Rincón (Director of the Transgenic/Knockout Mouse Facility, University of Vermont) for her scientific contributions pertaining to the generation of the transgenic mice, and John T. Dodge (University of Vermont) for his technical contributions in generating transgenic mice.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL60014 (Y.J.H.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1096OC on February 8, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: C.P. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. J.L.A. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. J.F.A. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.E.P. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. A.L.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. A.S.G. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. S.L.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. G.B.A. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. L.A.W. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.B. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. C.G.I. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. Y.M.W.J.-H. received $1,500 from Sepracor for a scientific lecture in 2005.

References

- 1.Davies DE. The bronchial epithelium in chronic and severe asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2001;1:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinton LJ, Jones MR, Simms BT, Kogan MS, Robson BE, Skerrett SJ, Mizgerd JP. Functions and regulation of NF-κB Rela during pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol 2007;178:1896–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans SE, Hahn PY, McCann F, Kottom TJ, Pavlovic ZV, Limper AH. Pneumocystis cell wall β-glucans stimulate alveolar epithelial cell chemokine generation through nuclear factor-κAB–dependent mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:490–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev 2004;18:2195–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. Rapid activation of nuclear factor-κB in airway epithelium in a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. Am J Pathol 2002;160:1325–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart L, Lim S, Adcock I, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Effects of inhaled corticosteroid therapy on expression and DNA-binding activity of nuclear factor κB in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart LA, Krishnan VL, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Activation and localization of transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB, in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das J, Chen CH, Yang L, Cohn L, Ray P, Ray A. A critical role for NF-κB in gata3 expression and Th2 differentiation in allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol 2001;2:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Cohn L, Zhang DH, Homer R, Ray A, Ray P. Essential role of nuclear factor κB in the induction of eosinophilia in allergic airway inflammation. J Exp Med 1998;188:1739–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donovan CE, Mark DA, He HZ, Liou HC, Kobzik L, Wang Y, De Sanctis GT, Perkins DL, Finn PW. Nf-κB/Rel transcription factors: C-Rel promotes airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol 1999;163:6827–6833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poynter ME, Cloots R, van Woerkom T, Butnor KJ, Vacek P, Taatjes DJ, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. NF-κB activation in airways modulates allergic inflammation but not hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol 2004;173:7003–7009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broide DH, Lawrence T, Doherty T, Cho JY, Miller M, McElwain K, McElwain S, Karin M. Allergen-induced peribronchial fibrosis and mucus production mediated by IκB kinase β–dependent genes in airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:17723–17728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ather JL, Pantano C, Poynter ME, Borwn AL, Janssen-Heininger YMW. Inducible expression of constitutively active IκB kinase β in airway epithelium in sufficient to drive inflammation in mice. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:A290. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu R, Smith D. Continuous multiplication of rabbit tracheal epithelial cells in a defined, hormone-supplemented medium. In Vitro 1982;18:800–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. A prominent role for airway epithelial NF-κB activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced airway inflammation. J Immunol 2003;170:6257–6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagers S, Lundblad L, Moriya HT, Bates JH, Irvin CG. Nonlinearity of respiratory mechanics during bronchoconstriction in mice with airway inflammation. J Appl Physiol 2002;92:1802–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomioka S, Bates JH, Irvin CG. Airway and tissue mechanics in a murine model of asthma: alveolar capsule vs. forced oscillations. J Appl Physiol 2002;93:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Z, Ma B, Homer RJ, Zheng T, Elias JA. Use of the tetracycline-controlled transcriptional silencer (tts) to eliminate transgene leak in inducible overexpression transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 2001;276:25222–25229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ray MK, Chen CY, Schwartz RJ, DeMayo FJ. Transcriptional regulation of a mouse Clara cell–specific protein (MCC10) gene by the nkx transcription factor family members thyroid transciption factor 1 and cardiac muscle-specific homeobox protein (CSX). Mol Cell Biol 1996;16:2056–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang F, Tang E, Guan K, Wang CY. Ikk β plays an essential role in the phosphorylation of Rela/p65 on serine 536 induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 2003;170:5630–5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stripp BR, Sawaya PL, Luse DS, Wikenheiser KA, Wert SE, Huffman JA, Lattier DL, Singh G, Katyal SL, Whitsett JA. Cis-acting elements that confer lung epithelial cell expression of the CC10 gene. J Biol Chem 1992;267:14703–14712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundblad LK, Thompson-Figueroa J, Allen GB, Rinaldi L, Norton RJ, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Airway hyperresponsiveness in allergically inflamed mice: the role of airway closure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bousquet J, Jeffery PK, Busse WW, Johnson M, Vignola AM. Asthma: from bronchoconstriction to airways inflammation and remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1720–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skerrett SJ, Liggitt HD, Hajjar AM, Ernst RK, Miller SI, Wilson CB. Respiratory epithelial cells regulate lung inflammation in response to inhaled endotoxin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;287:L143–L152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng DS, Han W, Chen SM, Sherrill TP, Chont M, Park GY, Sheller JR, Polosukhin VV, Christman JW, Yull FE, et al. Airway epithelium controls lung inflammation and injury through the NF-κB pathway. J Immunol 2007;178:6504–6513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagers SS, Haverkamp HC, Bates JH, Norton RJ, Thompson-Figueroa JA, Sullivan MJ, Irvin CG. Intrinsic and antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness are the result of diverse physiological mechanisms. J Appl Physiol 2007;102:221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda K, Haczku A, Lee JJ, Irvin CG, Gelfand EW. Strain dependence of airway hyperresponsiveness reflects differences in eosinophil localization in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;281:L394–L402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bousquet J, Chanez P, Lacoste JY, Barneon G, Ghavanian N, Enander I, Venge P, Ahlstedt S, Simony-Lafontaine J, Godard P, et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humbles AA, Lloyd CM, McMillan SJ, Friend DS, Xanthou G, McKenna EE, Ghiran S, Gerard NP, Yu C, Orkin SH, et al. A critical role for eosinophils in allergic airways remodeling. Science 2004;305:1776–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JJ, Dimina D, Macias MP, Ochkur SI, McGarry MP, O'Neill KR, Protheroe C, Pero R, Nguyen T, Cormier SA, et al. Defining a link with asthma in mice congenitally deficient in eosinophils. Science 2004;305:1773–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beeh KM, Beier J. Handle with care: targeting neutrophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe asthma? Clin Exp Allergy 2006;36:142–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brass DM, Hollingsworth JW, McElvania-Tekippe E, Garantziotis S, Hossain I, Schwartz DA. CD14 is an essential mediator of LPS induced airway disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L77–L83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tigani B, Hannon JP, Rondeau C, Mazzoni L, Fozard JR. Airway hyperresponsiveness to adenosine induced by lipopolysaccharide in Brown Norway rats. Br J Pharmacol 2002;136:111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Held HD, Uhlig S. Mechanisms of endotoxin-induced airway and pulmonary vascular hyperreactivity in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1547–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadeghi-Hashjin G, Folkerts G, Henricks PA, Verheyen AK, van der Linde HJ, van Ark I, Coene A, Nijkamp FP. Peroxynitrite induces airway hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs in vitro and in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:1697–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee KY, Ho SC, Lin HC, Lin SM, Liu CY, Huang CD, Wang CH, Chung KF, Kuo HP. Neutrophil-derived elastase induces TGF-β1 secretion in human airway smooth muscle via NF-κB pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park JA, He F, Martin LD, Li Y, Chorley BN, Adler KB. Human neutrophil elastase induces hypersecretion of mucin from well-differentiated human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro via a protein kinase cδ-mediated mechanism. Am J Pathol 2005;167:651–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao MX, Nadel JA. Neutrophil elastase induces muc5ac mucin production in human airway epithelial cells via a cascade involving protein kinase C, reactive oxygen species, and TNF-α–converting enzyme. J Immunol 2005;175:4009–4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers DF. Airway mucus hypersecretion in asthma: an undervalued pathology? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2004;4:241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reader JR, Tepper JS, Schelegle ES, Aldrich MC, Putney LF, Pfeiffer JW, Hyde DM. Pathogenesis of mucous cell metaplasia in a murine asthma model. Am J Pathol 2003;162:2069–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, Venkayya R, Brombacher F, Rennick DM, Sheppard D, Mohrs M, Donaldson DD, Locksley RM, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science 1998;282:2261–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tyner JW, Kim EY, Ide K, Pelletier MR, Roswit WT, Morton JD, Battaile JT, Patel AC, Patterson GA, Castro M, et al. Blocking airway mucous cell metaplasia by inhibiting EGFR antiapoptosis and IL-13 transdifferentiation signals. J Clin Invest 2006;116:309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Malarkey DE, Burch LH, Wong T, Longphre M, Ho SB, Foster WM. Neutrophil elastase induces mucus cell metaplasia in mouse lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;287:L1293–L1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borger P, Tamm M, Black JL, Roth M. Asthma: is it due to an abnormal airway smooth muscle cell? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roth M, Johnson PR, Borger P, Bihl MP, Rudiger JJ, King GG, Ge Q, Hostettler K, Burgess JK, Black JL, et al. Dysfunctional interaction of c/ebpα and the glucocorticoid receptor in asthmatic bronchial smooth-muscle cells. N Engl J Med 2004;351:560–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woodruff PG, Dolganov GM, Ferrando RE, Donnelly S, Hays SR, Solberg OD, Carter R, Wong HH, Cadbury PS, Fahy JV. Hyperplasia of smooth muscle in mild to moderate asthma without changes in cell size or gene expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shore SA. Airway smooth muscle in asthma—not just more of the same. N Engl J Med 2004;351:531–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.