Abstract

The group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) subtype, mGluR1, is highly expressed on the apical dendrites of olfactory bulb mitral cells and thus may be activated by glutamate released from olfactory nerve (ON) terminals. Previous studies have shown that mGluR1 agonists directly excite mitral cells. In the present study, we investigated the involvement of mGluR1 in ON-evoked responses in mitral cells in rat olfactory bulb slices using patch-clamp electrophysiology. In voltage-clamp recordings, the average EPSC evoked by single ON shocks or brief trains of ON stimulation (six pulses at 50 Hz) in normal physiological conditions were not significantly affected by the nonselective mGluR antagonist LY341495 (50–100 μM) or the mGluR1-specific antagonist LY367385 (100 μM); ON-evoked responses were attenuated, however, in a subset (36%) of cells. In the presence of blockers of ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptors, application of the glutamate uptake inhibitors THA (300 μM) and TBOA (100 μM) revealed large-amplitude, long-duration responses to ON stimulation, whereas responses elicited by antidromic activation of mitral/tufted cells were unaffected. Magnitudes of the ON-evoked responses elicited in the presence of THA–TBOA were dependent on stimulation intensity and frequency, and were maximal during high-frequency (50-Hz) bursts of ON spikes, which occur during odor stimulation. ON-evoked responses elicited in the presence of THA–TBOA were significantly reduced or completely blocked by LY341495 or LY367385 (100 μM). These results demonstrate that glutamate transporters tightly regulate access of synaptically evoked glutamate from ON terminals to postsynaptic mGluR1s on mitral cell apical dendrites. Taken together with other findings, the present results suggest that mGluR1s may not play a major role in phasic responses to ON input, but instead may play an important role in shaping slow oscillatory activity in mitral cells and/or activity-dependent regulation of plasticity at ON–mitral cell synapses.

INTRODUCTION

Axons from the olfactory receptor neurons form the olfactory nerve (ON), which terminates in the glomeruli of the main olfactory bulb. Within the glomeruli, ON nerve terminals form glutamatergic synapses with the apical dendrites of mitral and tufted cells, as well as with juxtaglomerular interneurons (Shipley et al. 1996). Anatomical and physiological studies have demonstrated that sensory transmission at ON–mitral cell synapses is mediated by glutamate acting at α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) ionotropic glutamate receptors (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1997; Bardoni et al. 1996; Berkowicz et al. 1994; Chen and Shepherd 1997; Ennis et al. 1996; Giustetto et al. 1997; Keller et al. 1998; Montague and Greer 1999).

Mitral cells also express high levels of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). Specifically, the group I mGluR subtype mGluR1 is expressed at high levels by mitral cells (Martin et al. 1992; Masu et al. 1991; Sahara et al. 2001; Shigemoto et al. 1992) and the splice variant mGluR1a has been localized postsynaptically at ON synapses (Van den Pol 1995). This expression pattern suggests that mGluR1 could mediate mitral cell responses to ON input. Consistent with this possibility, mGluR1 agonists depolarize mitral cells, whereas mGluR antagonists have been reported to attenuate ON-evoked spiking and slow oscillations in mitral cells (Heinbockel et al. 2004; Schoppa and Westbrook 2001). More recent studies suggest that ON-evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials in a subset of mitral cells exhibit a small mGluR1-mediated component in normal physiological conditions (De Saint Jan and Westbrook 2005). The latter study also demonstrated that mGluR1-mediated excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) elicited by single ON pulses were limited by glutamate-uptake mechanisms. Previous studies in the cerebellum and other CNS synapses (Batchelor and Garthwaite 1997; Huang et al. 2004; Karakossian and Otis 2004; Reichelt and Knopfel 2002; Shen and Johnson 1997; Tempia et al. 1998, 2001) demonstrated that mGluRs are preferentially activated by high-frequency synaptic activity. Therefore the goal of the present study was to investigate the contribution of mGluR1 in mitral cell responses elicited over a range of ON stimulation frequencies comparable to odor-evoked firing frequencies of olfactory receptor neurons in vivo (Duchamp-Viret et al. 1999). To address this question, patch-clamp electrophysiology was performed in rat olfactory bulb slices.

METHODS

Slice preparation

Sprague–Dawley rats (21–29 days old, Charles River Lab), of either sex, were decapitated in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and National Institutes of Health guidelines. Their olfactory bulbs were removed and immersed in sucrose–artificial cerebrospinal fluid (sucrose-ACSF) equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH = 7.38) as previously described (Ennis et al. 2001; Hayar et al. 2001). The sucrose-ACSF had the following composition (in mM): 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 2 KCl, 5 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 248 sucrose. Horizontal slices (400 μm thick) were cut with a microslicer (Vibratome 3000, St. Louis, MO). After a 15-min period of recovery at 30°C, slices were incubated until used at room temperature (22°C) in normal ACSF equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 (composition in mM: 120 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 5 BES, and 10 glucose; pH 7.27 and 300 mOsm (Heyward and Clarke 1995; Heyward et al. 2001). For recording, a single slice was placed in a recording chamber and continuously perfused at the rate of 1.5 ml/min with normal ACSF, maintained at 30 ± 0.2°C.

Electrophysiological recordings

Visually guided recordings from mitral cells in the mitral cell layer (MCL) were made with near-infrared differential interference contrast (NIR-DIC) optics, a 40 × water immersion objective, and Olympus microscope (BX50WI microscope, Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). NIR transillumination was at 900 nm (filter transmission, 850–950 nm) concentric with the objective and optimized for DIC. A 0.5-in. CCD camera (CCD100, Dage, Stamford, CT) fitted with a 3-to-1 zooming coupler (Optem, Fairport, NY), was used. The image was displayed on a monochrome monitor (Dage HR120, Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries with an inner filament (1.5 mm OD, Clark, Kent, UK) on a pipette puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) and were filled with a solution of the following composition (in mM): 125 K-gluconate, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 ATP, 0.2 GTP, 1 NaCl, and 0.2 EGTA; pH 7.2 and 296 mOsm. Tip diameter was 2–3 μm; tip resistance was 5–8 MΩ. Seal resistance was routinely >8 GΩ. Recordings were obtained using an Axopatch 200B or a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). The liquid junction potential was 9–10 mV, and all reported voltage measurements were not corrected for these potentials. Analog signals were low-pass Bessel filtered at 2 kHz. Data were collected through a Digidata 1200A/1322A interface (Axon Instruments), digitized at 5 kHz, and stored on computer hard disk using Clampex 8.0/9.0 software (Axon Instruments). The holding membrane potential was −60 mV. For whole cell current-clamp recording, holding currents (−80 to −100 pA) were generated under manual control of the recording amplifier. Data analysis was performed using Clampfit 8.0/9.0 analysis software (Axon Instruments). Because of the long duration of ON-evoked responses, statistical tests were performed on the charge transfer (integral) of the responses. The integral of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were calculated with Origin 7.0 (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA). However, in all cases examined (data from Figs. 1–3), statistical tests performed on the peak amplitude and charge transfer of evoked responses produced similar results. Numerical data are expressed as the means ± SE. Tests for statistical significance (P < 0.05) were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Student–Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons; in some cases Student’s t-test were used (Sigma Stat 2.03).

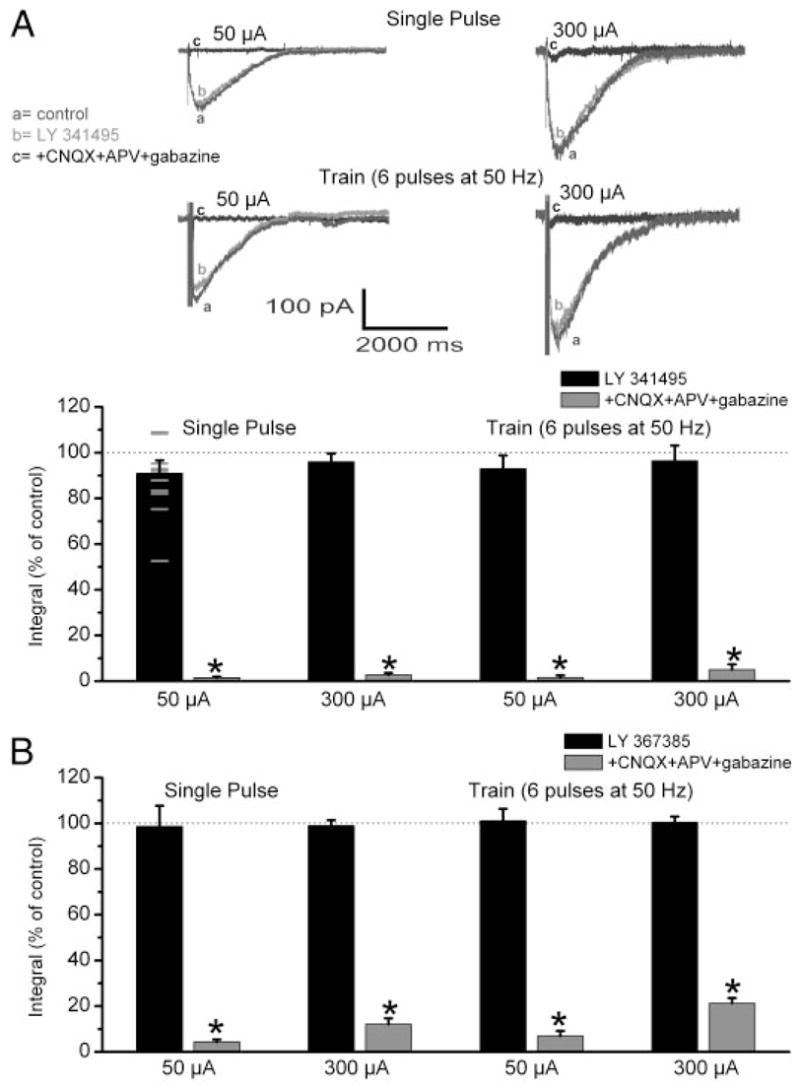

Fig. 1.

Metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) antagonists have modest effects on olfactory nerve (ON)–evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in mitral cells in normal media. A, top: EPSCs evoked by 50 or 300 μA ON stimulation; top row shows responses to single-pulse stimulation, whereas the bottom row shows responses elicited by train of 6 ON pulses at 50 Hz. Each panel shows responses in: control artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, a), the presence of the nonselective mGluR antagonist LY341495 (100 μM, b), and the presence of LY341495 and 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 100 μM (±)-2-amino-5-phosphopentanoic acid (APV), and 10 μM gabazine (c). Traces in all panels are averages of 5 responses to ON stimulation from the same mitral cell. Bottom bar graph shows the integral (see METHODS) of the ON-evoked EPSCs from 11 mitral cells (small horizontal lines plot the level of reduction by LY341495 for the 11 individual cells) for single-pulse stimulation and 5 mitral cells for 50-Hz stimulation. Note that LY341495 elicited a small but nonsignificant reduction (P > 0.05) in the mean size of the evoked EPSCs, whereas ionotropic glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor antagonists eliminated the evoked EPSCs. *P < 0.001 vs. EPSC in control ACSF or in the presence of LY341495; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001). B: bar graphs of group data from similar experiments investigating the effect of the selective mGluR1 antagonist, LY367385 (100 μM), on ON-evoked EPSCs elicited by single-pulse or 50-Hz ON stimulation (n = 5 mitral cells). LY367385 did not affect the integral of the evoked EPSCs (P > 0.05). *P < 0.002 vs. EPSC in control ACSF or in the presence of LY367385; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001).

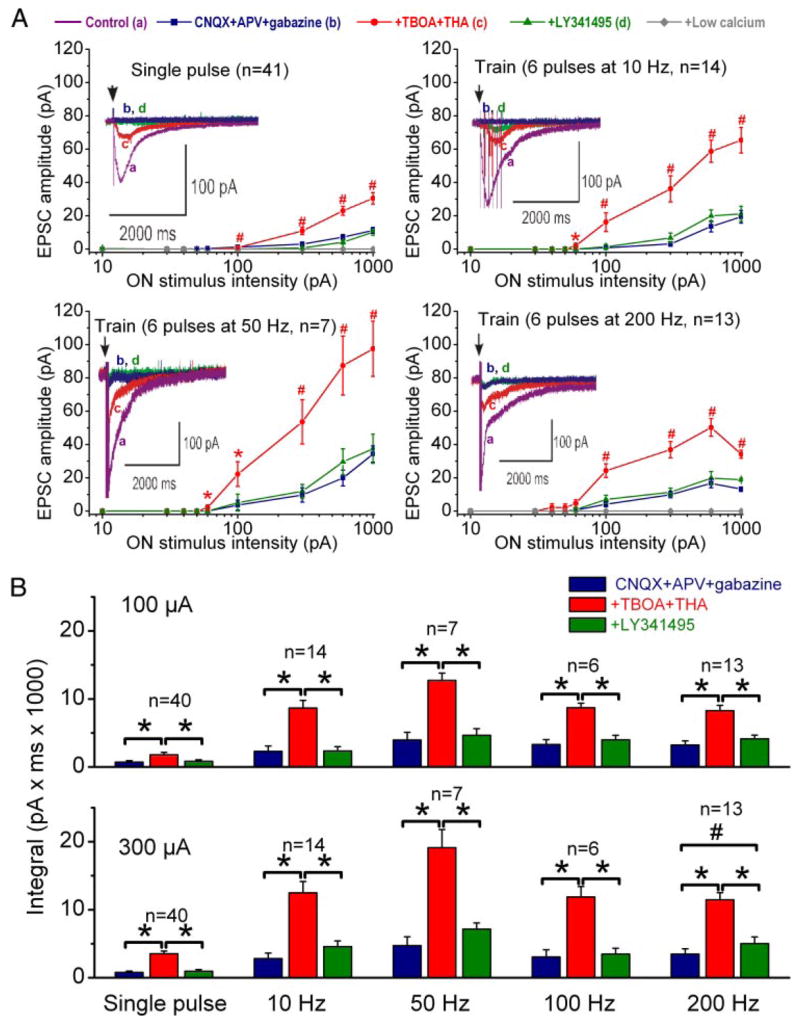

Fig. 3.

ON-evoked EPSCs elicited in the presence of glutamate uptake inhibitors are dependent on stimulation intensity and frequency. A: 4 top panels show plots of the peak amplitude of ON-evoked EPSCs as a function of ON stimulation intensity (10, 30, 40, 50, 60, 100, 300, 600, and 1,000 μA); each panel shows data for a different ON stimulation frequency. Insets (in each graph): traces of ON-evoked EPSCs in different pharmacological conditions; traces are averages of 5 ON-evoked EPSCs. Colored lines correspond to the pharmacological conditions indicated at the top; note that control data are not plotted on the line graphs. TBOA–THA significantly increases the ON-evoked EPSCs at a threshold intensity of 60–100 μA for all frequencies. Residual responses remaining in the presence of LY341495 and CNQX, APV, and gabazine were abolished by low-Ca2+ ACSF, as shown for the single-pulse and 200-Hz stimulation frequencies. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.001 vs. CNQX, APV, and gabazine. B: bar graph plots of the integral of ON-evoked EPSCs for 2 representative stimulation intensities. Note that the enhancement of the ON-evoked EPSCs is reversed by LY341495. *P < 0.001, #P < 0.05; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001).

Olfactory nerve and lateral olfactory tract stimulation

The olfactory nerve (ON) layer and the lateral olfactory tract were stimulated (Grass S8800 and PSIU7; Astro-Med, West Warwick, RI) using bipolar twisted stainless steel wire electrodes (75 μm diameter, insulated except for the tip) as previously described (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999a,b; Hayar et al. 2004a; Heinbockel et al. 2004). Constant-current stimuli, 0.1 ms in duration and 10–1,000 μA in intensity, were used. The ON stimulating electrode was positioned to lie radial to the mitral cell layer recording site, within the ON layer. In some experiments, a stimulation electrode was placed in the lateral olfactory tract (LOT) for antidromic activation of mitral and tufted cells as previously described (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999a, 2000). The following stimulation frequencies were used: 0.2-Hz single-pulse stimulation or six pulses delivered at 10, 50, 100, or 200 Hz; individual trains were delivered at 5-s intervals (i.e., 0.2 Hz). For each cell, responses to single-pulse and one-train frequency were tested. Responses were averaged for five trials at each stimulation frequency and intensity. The peak amplitude and integral (charge transfer) of evoked responses were calculated from such averages.

Drugs and solutions

Drugs and solutions were applied to the slice by switching the perfusion with a three-way electronic valve system. Recording medium and pipette solution components were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The following drugs were applied to the bath: D-threo-b-hydroxyaspartic acid (THA), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), gabazine (SR95531), and (±)-2-amino-5-phosphopentanoic acid (APV) from Sigma-Aldrich; (R,S)-( ±)-sulpiride, CGP55845, D-threo-β-benzyloxyaspartate (D-TBOA), tetrodotoxin (TTX), LY367385, and LY341495 from Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO). In some experiments (Fig. 3A), a low-Ca2+ ACSF was used in which CaCl2 was reduced to 0.5 mM and MgCl2 was increased to 8 mM.

RESULTS

ON-evoked responses exhibit a minimal mGluR component in normal media

We first investigated the involvement of mGluRs in ON-evoked responses recorded in normal ACSF. In voltage-clamp recordings (holding potential = −60 mV), single-pulse stimulation of the ON-evoked EPSCs with a mean onset latency of 3.9 ± 0.2 ms (n = 55); the amplitude of EPSCs increased with stimulation intensity (10–600 μA) and ranged from 20 to 150 pA. Comparable to previous reports (Carlson et al. 2000; De Saint Jan and Westbrook 2005), ON-evoked EPSCs were of long duration (≤2 s, Figs. 1 and 3). The effects of broad spectrum and selective mGluR antagonists were tested on EPSCs evoked by near-threshold (about 50 μA) and supra-threshold (about 300 μA) ON stimulation intensities. As shown in Fig. 1, the broad-spectrum mGluR antagonist LY341495 elicited a small (<10%) but nonsignificant (P > 0.05) overall decrease in the integral of ON-evoked EPSCs (Fig. 1A). However, in a subset of cells (four of 11 tested at 50 μA), LY341495 reduced the amplitude of the ON-evoked response by >15% (range: 17–47% reduction, mean reduction = 26.7 ± 7.1%). The mean baseline ON-evoked response in these four cells did not differ from that for the other seven cells. Additionally, there was no evidence for a bimodal distribution in the degree of inhibition by LY341495 (Fig. 1A) in the 11 cells tested, suggesting that the mGluR component of ON-evoked responses varies among mitral cells. Similar effects to those just described were observed after application of the mGluR1 selective antagonist LY367385 (Fig. 1B). Application of antagonists to ionotropic glutamate and β-aminobu-tyric acid (GABA) receptors (fast synaptic blockers; CNQX 10 μM, APV 100 μM, and gabazine 10 μM) reversibly eliminated (P < 0.001) the ON-evoked responses (Fig. 1). These results indicate that ON-evoked responses in only a subset (36%) of mitral cells exhibit a modest mGluR1-mediated component.

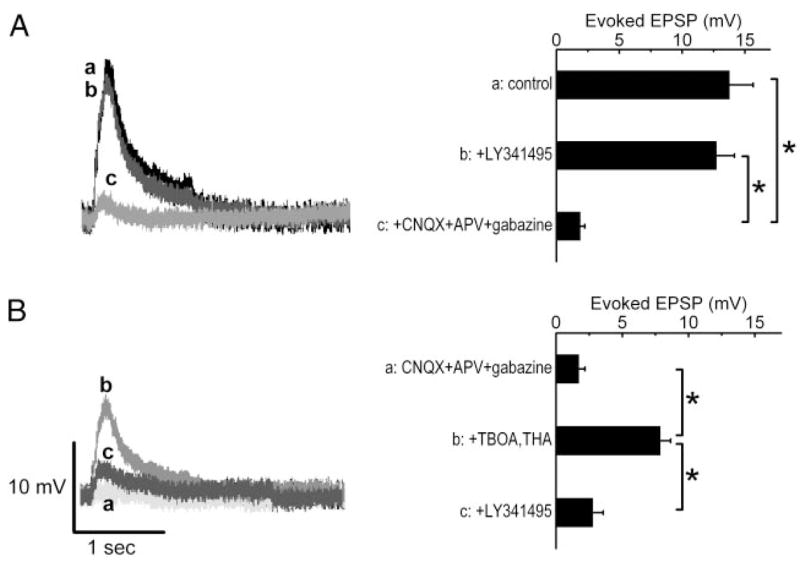

A recent study reported a modest mGluR1 component of ON-evoked responses in a subset of mitral cells recorded in current-clamp conditions (De Saint Jan and Westbrook 2005). Therefore we investigated the effects of LY341495 on ON-evoked EPSPs in mitral cells (Fig. 2). There was no difference (6.1 ± 5.5% reduction) between the amplitude of EPSPs evoked by single ON stimuli (60–100 μA) before or during application of 100 μM LY341495 (13.8 ± 1.9 vs. 12.7 ± 1.4 mV, n = 5, P > 0.05, Fig. 2A). ON-evoked EPSPs were completely attenuated by application of fast synaptic blockers (CNQX, APV, and gabazine: 1.9 ± 0.4 mV, n = 5, P < 0.001 vs. normal ACSF or LY341495).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of glutamate uptake reveals significant mGluR-mediated ON-evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) in mitral cells. A: ON-evoked EPSPs (a) were not significantly affected by the mGluR antagonist LY341495 (b) but were blocked by the fast synaptic blockers: CNQX + APV + gabazine (c). Right bar graphs: group data from 5 mitral cells. *P < 0.001; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001). B: ON-evoked EPSPs were almost completely blocked by the fast synaptic blockers (a). Application of the glutamate uptake blockers D-threo-β-benzyl-oxyaspartate (TBOA) + D-threo-b-hydroxyaspartic acid (THA) (b) significantly enhanced the evoked EPSP, an effect that was reversed by the mGluR antagonist LY341495 (c). Right bar graph: group data from 5 mitral cells in each condition. *P < 0.001; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001).

mGluRs are preferentially activated by high-frequency activity at many CNS synapses (Batchelor and Garthwaite 1997; Huang et al. 2004; Karakossian and Otis 2004; Reichelt and Knopfel 2002; Shen and Johnson 1997; Tempia et al. 1998, 2001) and previous studies have shown that odors produce brief bursts of high-frequency spikes (≤100 Hz) in olfactory receptor neurons in vivo (Duchamp-Viret et al. 1999). Therefore we investigated whether high-frequency stimulation of the ON in normal media evokes a more substantial mGluR component in mitral cells. As presented below, ON-evoked responses in mitral cells were near maximal with 50-Hz ON stimulation (Fig. 3). Therefore we tested whether mGluR antagonists alter the responses evoked by six ON pulses delivered at 50 Hz. As shown in Fig. 1, neither the mean amplitude nor the integral of responses evoked by 50-Hz stimulation in normal ACSF was significantly attenuated by LY341495 (100 μM, n = 5, P > 0.05) or LY367385 (100 μM, n = 5, P > 0.05). In the same cells, subsequent application of fast synaptic blockers largely eliminated the responses elicited by 50-Hz stimulation (Fig. 1). Taken together, these findings indicate that the involvement of mGluRs in ON-evoked excitation of mitral cells is modest under baseline physiological conditions in vitro.

Inhibition of glutamate transport and reuptake reveals “latent” mGluR components of ON-evoked responses in fast synaptic blockers

Activation of mGluRs by synaptically released glutamate is limited by glutamate reuptake mechanisms (Diamond and Jahr 2000; Huang et al. 2004; Reichelt and Knopfel 2002). We wondered whether glutamate reuptake limits activation of mGluRs on mitral cells. As shown in Fig. 3, we measured EPSCs evoked by ON stimulation over a range of stimulation intensities (10–1,000 μA) and stimulation frequencies (single pulse to 200 Hz; see METHODS) in the presence of fast synaptic blockers to isolate potential mGluR-mediated responses. These procedures were then repeated (in the presence of fast synaptic blockers) after bath application of the glutamate transporter inhibitors TBOA (100 μM; Jabaudon et al. 1999) and THA (300 μM; Balcar et al. 1977). TBOA and THA were applied together to maximize inhibition of glutamate uptake.

Consistent with results described above, application of fast synaptic blockers largely eliminated the ON-evoked responses, although at the high stimulation intensities (300 or 600 μA), a small EPSC (4–10 pA) remained (Figs. 3 and 4). As shown in Figs. 2B, 3, and 4, application of the glutamate uptake inhibitors TBOA (100 μM) and THA (300 μM) in the presence of fast synaptic blockers substantially increased ON-evoked responses. This increase was observed within 1–2 min of TBOA–THA application, appeared to be maximal by 3–5 min, and remained constant as long as the inhibitors were present in the bath. As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, TBOA–THA significantly increased the responses elicited by 60–100 μA and higher stimulation intensities for both single-pulse and high-frequency stimulation. The amplitude of ON-evoked responses in TBOA–THA increased with stimulation intensity. Responses also increased with stimulation frequency from 10 to 50 Hz, then declined thereafter. The TBOA–THA enhancement occurred for mitral cells that exhibited no residual EPSCs in the presence of fast synaptic blockers, as well as cells that had small residual responses. For example, with 50-μA single-pulse stimulation, TBOA–THA increased evoked EPSCs in seven of 33 cells with no residual responses in fast synaptic blockers, and in eight of eight cells with small residual responses. With 50-μA, 10-Hz stimulation, TBOA–THA increased evoked responses in five of 11 cells lacking, and three of three cells exhibiting residual responses in the presence of fast synaptic blockers. The ON-evoked responses revealed in the presence of TBOA–THA were eliminated by LY341495 (Figs. 2B and 3). In nearly all cases, the EPSCs were significantly reduced to values equivalent to those elicited in the presence of fast synaptic blockers alone (Figs. 2B and 3). The small residual responses that persisted in the presence of fast synaptic blockers and LY341495 were abolished by application of low-Ca2+ ACSF (Fig. 3A, n = 7 mitral cells). The residual responses were also abolished by application of TTX (1 μM, data not shown).

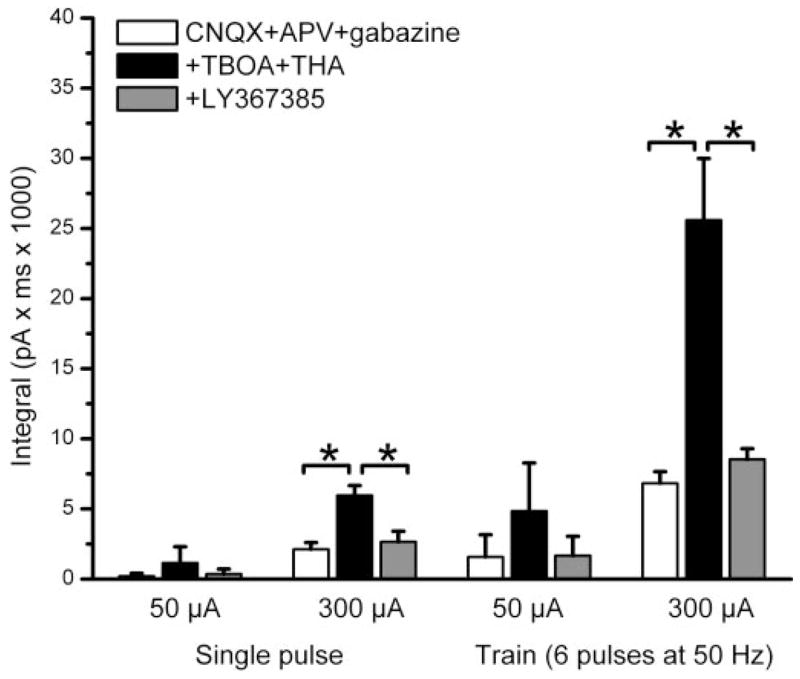

Fig. 4.

Enhancement of ON-evoked EPSCs by glutamate uptake inhibitors is reversed by the mGluR1 selective antagonist LY367385. Bar graph plots of the integral of ON-evoked EPSCs elicited by 50 or 300 μA intensity, single-pulse or 50-Hz stimulation (n = 5 mitral cells in each condition). Application of TBOA (100 μM) and THA (300 μM) enhanced ON-evoked EPSCs in the presence of CNQX (10 μM), APV (100 μM), and gabazine (10 μM); this effect reached statistical significance for the 300-μA-intensity stimulation. LY367385 reversed the TBOA–THA enhancement of evoked EPSCs. *P < 0.05; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001).

ON-evoked responses in TBOA–THA are mediated by activation of mGluR1

The preceding results with TBOA–THA demonstrate that glutamate reuptake/transport inhibitors normally limit glutamate’s access to mGluRs in mitral cells. Mitral cells express several mGluR subtypes, but mGluR1a is densely expressed by these cells and is localized postsynaptically to ON synapses (Van den Pol 1995). Therefore we investigated the involvement of mGluR1 in a set of experiments similar to those just described. We compared a more limited range of stimulation intensities (50 and 300 μA) and frequencies (single pulse and 50 Hz). As shown in Fig. 4, the mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (100 μM) significantly attenuated ON-evoked EPSCs recorded in the presence of fast synaptic blockers and TBOA–THA. There were no significant differences in the amplitude or integral of the responses evoked in the presence of fast synaptic blockers versus fast blockers, TBOA–TBA and LY367385 (Fig. 4). These results indicate that the ON-evoked responses enhanced by TBOA–THA are mediated by mGluR1.

D2 receptor and GABAB-receptor–mediated presynaptic inhibition does not limit expression of mGluR-mediated responses to ON input in the presence of fast synaptic blockers

Previous studies demonstrate that glutamate release from ON terminals is presynaptically regulated by GABA and do-pamine released from periglomerular neurons (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 2000; Ennis et al. 2001; Murphy et al. 2005; Wachowiak et al. 2005). This inhibition is tonically active, at least for GABAB receptors on ON terminals, and is maximal for repetitive stimuli at frequencies similar to those in the present experiments (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 2000). Thus we wondered whether presynaptic inhibition might limit glutamate release from ON terminals, and thus activation of postsynaptic mGluRs, during bursts of ON activity. Application of the D2 receptor antagonist sulpiride (100 μM) and the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP55685 (10 μM) in the presence of fast synaptic blockers did not increase EPSCs elicited by single-pulse or 200-Hz ON stimulation (Fig. 5A). Subsequent addition of TBOA and THA significantly increased the EPSCs (P < 0.05, n = 3). The size of the EPSCs elicited in the fast synaptic blockers + TBOA–THA + sulpiride-CGP55685 were larger than those elicited in the same conditions without sulpiride-CGP55685 (Fig. 5B). This suggests that in the presence of fast synaptic blockers and glutamate uptake inhibitors, activation of mGluRs in response to ON input is capable of stimulating sufficient GABA and/or dopamine release from juxtaglomerular neurons to presynaptically inhibit ON terminals. The responses enhanced by TBOA–THA were totally blocked by LY341495 (50 μM, n = 3; Fig. 5A). These experiments indicate that in the presence of fast synaptic blockers presynaptic inhibition of ON terminals does not limit activation of mGluRs in response to ON input. However, when extracellular glutamate levels are increased by TBOA–THA in the same condition, activation of mGluRs can limit ON-evoked responses by presynaptic inhibition of ON terminals.

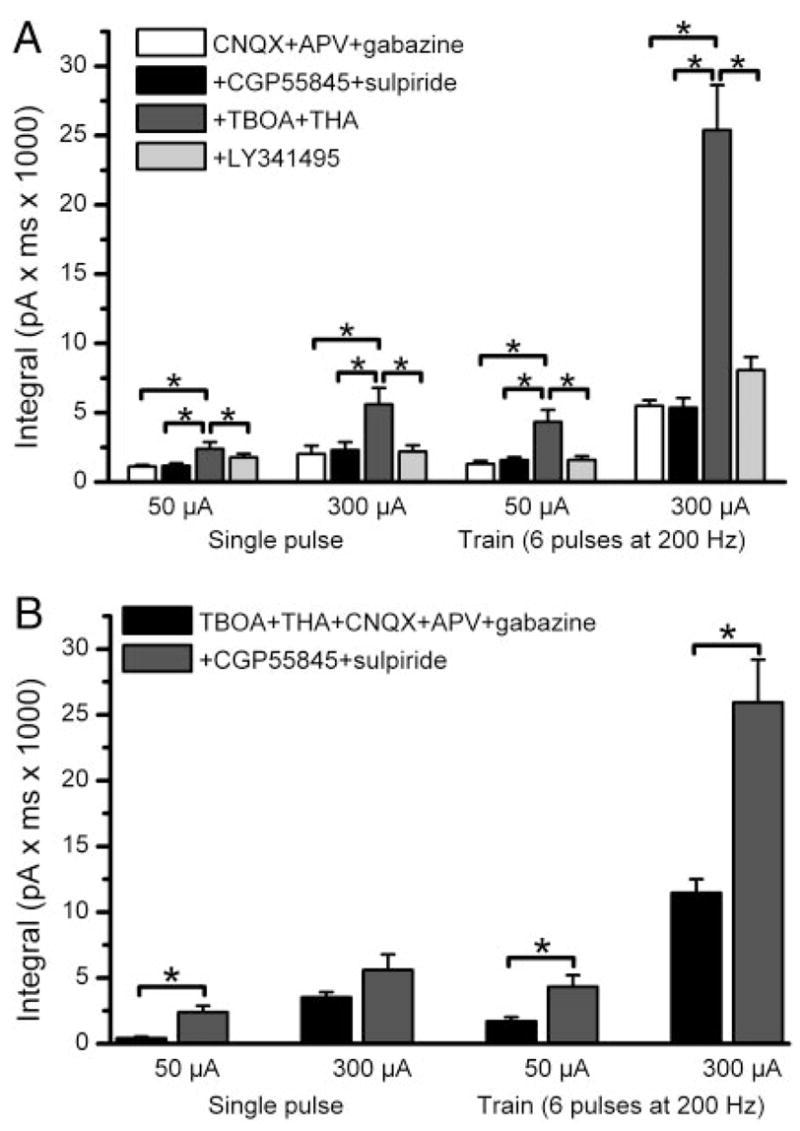

Fig. 5.

Blockade of presynaptic inhibition does not alter ON-evoked EPSCs elicited in the presence of ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptor antagonists. A: bar graph shows the integral of ON-evoked EPSCs in mitral cells in the 4 pharmacological conditions indicated at the top of the figure. In the presence of CNQX, APV, and gabazine, additional application of the D2 dopamine receptor antagonist sulpiride (100 μM) and the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP55485 (10 μM) had no substantial effect on EPSCs elicited by 50 or 300 μA intensity, single-pulse or 200-Hz ON stimulation (n = 3 mitral cells in each condition). Subsequent addition of TBOA (100 μM) and THA (300 μM) enhanced the ON-evoked EPSCs, an effect reversed by application of LY341495. *P < 0.05; Newman–Keul post hoc comparisons following a one-way ANOVA for drug treatment (P < 0.001). B: bar graphs showing that the ON-evoked EPSC in the presence of TBOA–THA + CGP-sulpiride + CNQX–APV–gabazine (data from A above) are larger than those in TBOA–THA + CNQX–APV–gabazine (data from Fig. 3). *P < 0.01, unpaired t-test.

Lateral olfactory tract (LOT) stimulation-evoked EPSCs are not altered by inhibition of glutamate uptake

In addition to glutamate input from the ON, recurrent excitatory interactions occur among mitral and tufted cells by spillover of dendritically released glutamate (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999b; Carlson et al. 2000; Hayar et al. 2005). To investigate the relative role of glutamate released by ON terminals versus mitral/tufted cell dendrites, we measured glutamatergic excitatory responses elicited by LOT-evoked antidromic activation of mitral/tufted cells (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999a, 2000; Carlson et al. 2000). In this experiment, we compared responses elicited by single-pulse and 50-Hz stimulation using a range of stimulation intensities (Fig. 6). In normal ACSF, the amplitude of LOT-evoked EPSCs was typically 50% smaller than that elicited by ON stimulation at identical stimulation intensities or frequencies. Similar to ON-evoked responses, application of fast synaptic blockers eliminated LOT-evoked excitatory responses in all nine mitral cells tested, in agreement with previous findings (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999b; Carlson et al. 2000; Laaris et al. 2002). Unlike ON-evoked responses, addition of TBOA–THA did not increase the amplitude of the responses elicited by LOT stimulation (Fig. 6). LOT-evoked responses fully or partially recovered within 20 min after washout of fast synaptic blockers (n = 5). These results indicate that glutamate released by LOT stimulation in the presence of fast synaptic blockers does not engage a significant mGluR-mediated response even when glutamate-uptake mechanisms are inhibited.

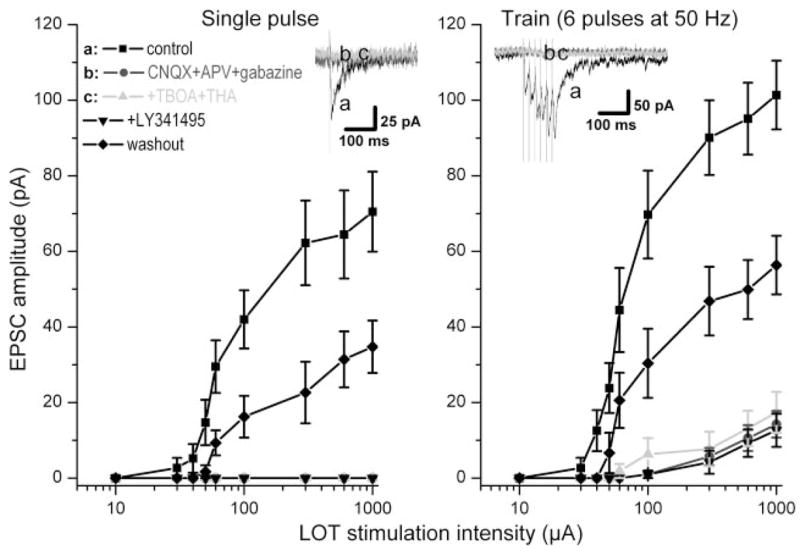

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of glutamate uptake does not enhance EPSCs evoked by antidromic activation of mitral/tufted cells in the presence of ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptor antagonists. Line graph showing the peak amplitude of EPSCs in mitral cells evoked by stimulation of the lateral olfactory tract (LOT) at different intensities (10, 30, 40, 50, 60, 100, 300, 600, and 1,000 μA) with single pulses (left) or with 6 pulses at 50 Hz (right); n = 9 mitral cells in all conditions. Individual lines correspond to the pharmacological conditions indicated at the top left of the figure. Typical LOT-evoked EPSCs (stimulation intensity: 300 μA) are shown in insets in both panels and correspond to conditions indicated at top left in each panel by letters a–c. LOT-evoked EPSCs were largely attenuated by application of CNQX (10 μM), APV (100 μM), and gabazine. Subsequent application of TBOA (100 μM) and THA (300 μM) had no significant effect on the EPSCs, nor did further application of LY341495. LOT-evoked responses partially recovered to baseline values within 10–20 min after washout with normal ACSF (n = 5).

DISCUSSION

The present results demonstrate that a single ON spike or brief high-frequency bursts of ON stimulation engage a modest mGluR-mediated current in a subset of mitral cells in normal physiological conditions in vitro. However, in the presence of antagonists of ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptors, inhibition of glutamate uptake disclosed substantial ON-evoked, mGluR-mediated currents. Such responses appeared to be triggered specifically by ON inputs because antidromic activation of mitral/tufted cells did not elicit responses in identical conditions. Taken together, these results indicate that glutamate uptake and transport mechanisms significantly limit mGluR-mediated currents in mitral cells in response to ON input.

The present results indicate that the involvement of mGluR1 in ON-evoked responses of mitral cells is modest under normal physiological conditions in rat olfactory bulb slices. Although LY341495 or LY367385 reduced ON-evoked responses in a subset of mitral cells, overall neither of these mGluR antagonists significantly reduced the mean ON-evoked responses of the overall population of cells tested. It is possible that the large AMPA/NMDA receptor-mediated component that dominates ON-evoked responses may prevent consistent detection of a relatively small reduction of the overall response by mGluR1 antagonists in most mitral cells. De Saint Jan and Westbrook (2005) recently reported that a subset of mouse mitral cells had small residual ON-evoked EPSPs in the presence of APV and NBQX that were eliminated by LY367385. The later mitral cell subset may correspond to mitral cells (four of 11) in the present study that exhibited modest reductions in ON-evoked responses during LY341495 application. Thus both our results and those of De Saint Jan and Westbrook (2005) appear to be similar in that only a subset of the mitral cell population exhibit a mGluR1-mediated ON-response component. Expression of an ON-evoked, mGluR-mediated response component in a subset of mitral cells may account for findings by Carlson et al. (2000) that spontaneous or ON-evoked long-lasting depolarizations in mitral cells were not affected by mGluR antagonism. Differences among the three studies may be explained by recording conditions (ACSF composition, temperature), species, and age of animals.

Previous studies suggest that MOB expresses three of the five known glutamate transporters: GLAST, GLT1, and EAAC1 (Utsumi et al. 2001). GLAST and GLT1 are robustly expressed in glial cells in the glomerular layer, whereas EAAC1 is expressed in neurons throughout the bulb (Utsumi et al. 2001). The present findings demonstrate that glutamate-uptake mechanisms potently regulate access of glutamate released from ON terminals to postsynaptic mGluR1s on mitral cell apical dendrites. Thus application of the glutamate-uptake inhibitors THA and TBOA revealed mGluR1-dependent, ON-evoked EPSCs in mitral cells in the presence of ionotropic glutamate and GABA receptor antagonists. These findings are in excellent agreement with a similar study by De Saint Jan and Westbrook (2005). The present findings indicate that there is a critical threshold for ON-evoked activation of mGluR1 on mitral cells. In the presence of glutamate-uptake and fast synaptic blockers, expression of mGluR1-mediated EPSCs required stimulation of ≥50 μA, suggesting that these responses require simultaneous activation of multiple ON axons converging on the same glomerulus. The amplitude of mGluR1-mediated responses also varied with stimulation frequency and was maximal with brief bursts of ON activity at frequencies from 10 to 50 Hz. This suggests that odors triggering bursts of spikes in olfactory receptor neurons in vitro (Reisert and Matthews 2001) and TTX-sensitive synchronized oscillatory activity in vivo (Dorries and Kauer 2000) will be most effective in activating mGluR1 in the glomeruli.

An important question is the source of glutamate mediating the mGluR1 responses revealed in the presence of THA–TBOA. Tufted cells, including external tufted cells in the glomeruli, as well as mitral cells release glutamate in response to ON stimulation (Hayar et al. 2004b, 2005; Isaacson 1999; Isaacson and Strowbridge 1998; Murphy et al. 2005). It is possible therefore that glutamate spillover among mitral/tufted cells could have mediated the ON-evoked responses in the presence of THA–TBOA. For example, back-propagating spikes in mitral cell apical dendrites are known to evoke spillover-mediated excitation (Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999; Friedman and Strowbridge 2000; Isaacson 1999; Salin et al. 2001). In this case, glutamate spillover evoked by antidromic activation of mitral/tufted cells should produce responses similar to those evoked by ON stimulation. The present findings, however, indicate that antidromic activation of mitral/tufted cells by LOT stimulation did not produce significant responses in the presence of THA–TBOA. Thus glutamate released from mitral/tufted cells under these conditions might not be sufficient to activate mGluR1 receptors. ON stimulation activates glutamatergic external tufted cells (Hayar et al. 2004a,b) and it is possible that ON stimulation activates more mitral/tufted cells than LOT stimulation. As a consequence, the concentration of glutamate released in a glomerulus might be higher with ON stimulation.

Previous studies demonstrate that mitral and tufted cells robustly express mGluR1 (Martin et al. 1992; Masu et al. 1991; Sahara et al. 2001; Shigemoto et al. 1992; Van den Pol 1995). The level of mGuR1a expression in mitral cells is higher than that in other regions of the brain with the exception of the cerebellum (Van den Pol 1995). Within the glomeruli, mGluR1a has been specifically localized at the EM level to postsynaptic portions of mitral cell apical dendrites receiving input from ON terminals (Van den Pol 1995). Bath application of mGluR1 agonists elicited inward currents and directly depolarized mitral cells (Heinbockel et al. 2004; Schoppa and Westbrook 1997). In view of these observations, it is surprising that ON stimulation in normal media does not engage more robust mGluR1-mediated excitation of mitral cells than observed here or by others (De Saint Jan and Westbrook 2005). The EC50 of mGluR1 for glutamate (about 10 μM; Pin and Duvoisin 1995) is higher than that of NMDA receptors (0.6–2.9 μM depending on receptor subtype; Anson et al. 1998; Kutsuwada et al. 1992; McBain and Mayer 1994; Moriyoshi et al. 1991), but much less than that for AMPA receptors (>100 μM; Patneau and Mayer 1990). In view of the relative affinities of mGluR1, AMPA, and NMDA receptors for glutamate and the fact that synaptically released glutamate from ON terminals readily activates AMPA and NMDA receptors on mitral cell apical dendrites in normal physiological conditions, it seems unlikely that the lack of mGluR1 responses arises from insufficient synaptic glutamate concentration to activate these receptors. Because mGluRs are coupled to IP3 and intracellular calcium release pathways, it is plausible that mGluRs may bind glutamate but do not generate a measurable current (Wang et al. 2000), especially if coupling between mGluRs and the ion channels mediating the current is nonlinear. An additional possibility is that the intracellular components involved in mGluR1 transduction could run down as a result of dialysis during whole cell patch-clamp recordings.

Rather than playing a major role in “fast” synaptic transmission, an alternative possibility is that mGluR1s may play a more influential role in shaping slow temporal patterns of mitral cell responses to ON input or in regulating activity-dependent plasticity at ON–mitral cell synapses. Mitral cell spontaneous firing is reduced by mGluR antagonists, suggesting that mitral cells are tonically excited by endogenously released glutamate acting at mGluR1 (Heinbockel et al. 2004). Slow (2-Hz) mitral cell oscillations elicited by ON stimulation are reduced in frequency and duration by mGluR antagonists (Schoppa and Westbrook 2001). Recent findings also suggest that mGluRs are involved in the expression of long-term depression at ON–mitral cell synapses (Mutoh et al. 2005). Finally, it is noteworthy that ON deafferentation downregulates expression of mGluR1, but does not affect expression of AMPA or NMDA receptors, in the glomeruli (Casabona et al. 1998; Ferraris et al. 1997). The expression of mGluR1, like the regulation of dopamine in periglomerular neurons (Baker 1990; Baker et al. 1983, 1984; Brunjes et al. 1985), is regulated by sensory input from the ON. Thus the role of mGluR1 may be more important in signaling tonic levels of sensory input than phasic synaptic responses.

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants DC-03195, DC-00347, DC-06356, and DC-07123.

References

- Anson LC, Chen PE, Wyllie DJ, Colquhoun D, Schoepfer R. Identification of amino acid residues of the NR2A subunit that control glutamate potency in recombinant NR1/NR2A NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 1998;18:581–589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00581.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Ennis M, Shipley MT. Current-source density analysis in the rat olfactory bulb: laminar distribution of kainate/AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated currents. J Neurophysiol. 1999a;81:15–28. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Ennis M, Shipley MT. Dendrodendritic recurrent excitation in mitral cells of the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 1999b;82:489–494. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Zhou FM, Priest CA, Ennis M, Shipley MT. Tonic and synaptically evoked presynaptic inhibition of sensory input to the rat olfactory bulb via GABA(B) heteroreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1194–1203. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska VA, Ennis M, Shipley MT. Glomerular synaptic responses to olfactory nerve input in rat olfactory bulb slices. Neuroscience. 1997;79:425–434. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H. Unilateral neonatal olfactory deprivation alters tyrosine hydroxylase expression but not aromatic amino acid decarboxylase or GABA immuno-reactivity. Neuroscience. 1990;36:761–771. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H, Kawano T, Albert V, Joh TH, Reis DJ, Margolis FL. Olfactory bulb dopamine neurons survive deafferentation-induced loss of tyrosine hydroxylase. Neuroscience. 1984;11:605–615. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H, Kawano T, Margolis FL, Joh TH. Transneuronal regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in olfactory bulb of mouse and rat. J Neurosci. 1983;3:69–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00069.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcar VJ, Johnston GAR, Twitchin B. Stereospecificity of the inhibition of L-glutamate and L-aspartate high affinity uptake in rat brain slices by threo-3-hydroxyasparate. J Neurochem. 1977;28:1145–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoni R, Puopolo M, Magherini PC, Belluzzi O. Potassium currents in periglomerular cells of frog olfactory bulb in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1996;210:95–98. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor AM, Garthwaite J. Frequency detection and temporally dispersed synaptic signal association through a metabotropic glutamate receptor pathway. Nature. 1997;385:74–77. doi: 10.1038/385074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowicz DA, Trombley PQ, Shepherd GM. Evidence for glutamate as the olfactory receptor cell neurotransmitter. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:2557–2561. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunjes PC, Smith-Crafts LK, McCarty R. Unilateral odor deprivation: effects on the development of olfactory bulb catecholamines and behavior. Dev Brain Res. 1985;22:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GC, Shipley MT, Keller A. Long-lasting depolarizations in mitral cells of the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2011–2021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-02011.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casabona G, Catania MV, Storto M, Ferraris N, Perroteau I, Fasolo A, Nicoletti F, Bovolin P. Deafferentation up-regulates the expression of the mGlu1a metabotropic glutamate receptor protein in the olfactory bulb. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:771–776. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WR, Shepherd GM. Membrane and synaptic properties of mitral cells in slices of rat olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 1997;745:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Saint Jan D, Westbrook GL. Detecting activity in olfactory bulb glomeruli with astrocyte recording. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2917–2924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5042-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Synaptically released glutamate does not overwhelm transporters on hippocampal astrocytes during high-frequency stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2835–2843. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorries KM, Kauer JS. Relationships between odor-elicited oscillations in the salamander olfactory epithelium and olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:754–765. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchamp-Viret D, Chaput MA, Duchamp A. Odor response properties of rat olfactory receptor neurons. Science. 1999;284:2171–2174. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis M, Zhou FM, Ciombor KJ, Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Hayar A, Borrelli E, Zimmer LA, Margolis F, Shipley MT. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of olfactory nerve terminals. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2986–2997. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.6.2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis M, Zimmer LA, Shipley MT. Olfactory nerve stimulation activates rat mitral cells via NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in vitro. Neuroreport. 1996;7:989–992. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199604100-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris N, Perroteau I, De Marchis S, Fasolo A, Bovolin P. Glutamatergic deafferentation of olfactory bulb modulates the expression of mGluR1a mRNA. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1949–1953. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705260-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Strowbridge BW. Functional role of NMDA autoreceptors in olfactory mitral cells. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:39–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustetto M, Bovolin P, Fasolo A, Bonino M, Cantino D, Sassoe-Pognetto M. Glutamate receptors in the olfactory bulb synaptic circuitry: heterogeneity and synaptic localization of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 1 and AMPA receptor subunit 1. Neuroscience. 1997;76:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayar A, Heyward PM, Heinbockel T, Shipley MT, Ennis M. Direct excitation of mitral cells via activation of alpha1-noradrenergic receptors in rat olfactory bulb slices. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2173–2182. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayar A, Karnup S, Ennis M, Shipley MT. External tufted cells: a major excitatory element that coordinates glomerular activity. J Neurosci. 2004b;24:6676–6685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1367-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayar A, Karnup S, Shipley MT, Ennis M. Olfactory bulb glomeruli: external tufted cells intrinsically burst at theta frequency and are entrained by patterned olfactory input. J Neurosci. 2004a;24:1190–1199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4714-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayar A, Shipley MT, Ennis M. Olfactory bulb external tufted cells are synchronized by multiple intraglomerular mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8197–8208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2374-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinbockel T, Heyward P, Conquet F, Ennis M. Regulation of main olfactory bulb mitral cell excitability by metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3085–3096. doi: 10.1152/jn.00349.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyward PM, Clarke IJ. A transient effect of estrogen on calcium currents and electrophysiological responses to gonadotropin-releasing hormone in ovine gonadotropes. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62:543–552. doi: 10.1159/000127050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyward PM, Ennis M, Keller A, Shipley MT. Membrane bistability in olfactory bulb mitral cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5311–5320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05311.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Sinha SR, Tanaka K, Rothstein JD, Bergles DE. Astrocyte glutamate transporters regulate metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated excitation of hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4551–4559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5217-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS. Glutamate spillover mediates excitatory transmission in the rat olfactory bulb. Neuron. 1999;23:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Strowbridge BW. Olfactory reciprocal synapses: dendritic signaling in the CNS. Neuron. 1998;20:749–761. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabaudon D, Shimamato K, Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Scanzini M, Gahwiler BH, Gerber U. Inhibition of uptake unmasks rapid extracellular turnover of glutamate of non-vesicular origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8733–8738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakossian MH, Otis TS. Excitation of cerebellar interneurons by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1558–1565. doi: 10.1152/jn.00300.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Yagodin S, Aroniadou-Anderjaska A, Zimmer LA, Ennis M, Sheppard NF, Shipley MT. Functional organization of rat olfactory bulb glomeruli revealed by optical imaging. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2602–2612. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsuwada T, Kashiwabuchi N, Mori H, Sakimura K, Kushiya E, Araki K, Meguro H, Masaki H, Kumanishi T, Arakawa M, Mishina M. Molecular diversity of the NMDA receptor channel. Nature. 1992;358:36–41. doi: 10.1038/358036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaris N, Ennis M. Distinct activity patterns evoked by activation of mitral/tufted cell and centrifugal fiber inputs to main olfactory bulb (MOB) granule cells. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2002;561:14. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Blackstone CD, Huganir RL, Price DL. Cellular localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat brain. Neuron. 1992;9:259–270. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90165-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masu M, Tanabe Y, Tsuchida K, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S. Sequence and expression of a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 1991;349:760–765. doi: 10.1038/349760a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain CJ, Mayer ML. N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor structure and function. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:723–760. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague AA, Greer CA. Differential distribution of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:233–246. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990308)405:2<233::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyoshi K, Masu M, Ishii T, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rat NMDA receptor. Nature. 1991;354:31–37. doi: 10.1038/354031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GJ, Darcy DP, Isaacson JS. Intraglomerular inhibition: signaling mechanisms of an olfactory microcircuit. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:354–364. doi: 10.1038/nn1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh H, Yuan Q, Knopfel T. Long-term depression at olfactory nerve synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4252–4259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4721-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patneau DK, Mayer ML. Structure–activity relationships for amino acid transmitter candidates acting at N-methyl-D-aspartate and quisqualate receptors. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2385–2399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02385.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt W, Knopfel T. Glutamate uptake controls expression of a slow postsynaptic current mediated by mGluRs in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1974–1980. doi: 10.1152/jn.00704.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisert J, Matthews HR. Response properties of isolated mouse olfactory receptor cells. J Physiol. 2001;530:113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0113m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara Y, Kubota T, Ichikawa M. Cellular localization of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1, 2/3, 5 and 7 in the main and accessory olfactory bulb of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2001;312:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin PA, Lledo PM, Vincent JD, Charpak S. Dendritic glutamate autoreceptors modulate signal processing in rat mitral cells. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1275–1282. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa NE, Westbrook GL. Modulation of mEPSCs in olfactory bulb mitral cells by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1468–1475. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.3.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa NE, Westbrook GL. Glomerulus-specific synchronization of mitral cells in the olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2001;31:639–651. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K-Z, Johnson SW. A slow excitatory postsynaptic current mediated by G-protein-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors in rat ventral teg-mental dopamine neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Distribution of the mRNA for a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) in the central nervous system: an in situ hybridization study in adult and developing rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;322:121–135. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley MT, McLean JH, Zimmer LA, Ennis M. The olfactory system. In: Swanson LW, Bjorklund A, Hokfelt T, editors. Integrated Systems of the CNS. III. New York: Elsevier; 1996. pp. 469–575. [Google Scholar]

- Tempia F, Alojado ME, Strata P, Knopfel T. Characterization of the mGluR(1)-mediated electrical and calcium signaling in Purkinje cells of mouse cerebellar slices. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1389–1397. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.3.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempia F, Miniaci MC, Anchisi D, Strata P. Postsynaptic current mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:520–528. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsumi M, Ohno K, Onchi H, Sato K, Tohyama M. Differential expression patterns of three glutamate transporters (GLAST, GLT1 and EAAC1) in the rat main olfactory bulb. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;92:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Pol AN. Presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in adult and developing neurons: autoexcitation in the olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:253–271. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachowiak M, McGann JP, Heyward PM, Shao Z, Puche AC, Shipley MT. Inhibition of olfactory receptor neuron input to olfactory bulb glomeruli mediated by suppression of presynaptic calcium influx. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2700–2712. doi: 10.1152/jn.00286.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Denk W, Hausser M. Coincidence detection in single dendritic spines mediated by calcium release. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1266–1273. doi: 10.1038/81792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]