Abstract

The red deer is well suited to scientific study, given its economic importance as an animal to be hunted, and because it has a rich genetic heritage. However, there has been little research into the prenatal development of the stomach of ruminants in general, and none for the red deer. For this reason, we undertook histological evaluation of the ontogenesis of the abomasum in red deer. Histomorphometric and immunohistochemical analyses were carried out on 50 embryos and fetuses from the initial stages of prenatal life until birth. The animals were divided for test purposes into five experimental groups: group I [1.4–3.6 cm crown–rump length (CRL); 30–60 days, 1–25% of gestation]; group II (4.5–7.2 cm CRL; 67–90 days, 25–35% of gestation); group III (8–19 cm CRL; 97–135 days, 35–50% of gestation); group IV (21–33 cm CRL; 142–191 days, 50–70% of gestation) group V (36–40 cm CRL; 205–235 days, 75–100% of gestation). In the organogenesis of the primitive gastric tube of red deer, differentiation of the abomasum took place at 67 days, forming a three-layered structure: the epithelial layer (pseudostratified), pluripotential blastemic tissue and serosa. The abomasal wall displayed the primitive folds of the abomasum and by 97 days abomasal peak areas were observed on the fold surface. At 135 days the abomasal surface showed a single mucous cylindrical epithelium, and gastric pits were observed in the spaces between abomasal areas. At the bottom of these pits the first outlines of glands could be observed. The histodifferentiation of the lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa showed patterns similar to those described for the forestomach of red deer. The abomasum of red deer during prenatal life, especially from 67 days of gestation, was shown to be an active structure with full secretory capacity. Its histological development, its secretory capacity (as revealed by the presence of neutral mucopolysaccharides) and its neuroendocrine nature (as revealed by the presence of positive non-neuronal enolase cells and the neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide and neuropeptide Y) were in line with the development of the rumen, reticulum and omasum. Gastrin-immunoreactive cells first appeared in the abomasum at 142 days, and the number of positive cells increased during development. As for the number of gastrin cells, plasma gastrin concentrations increased throughout prenatal life. However, its prenatal development was later than that of the abomasum in sheep, goat and cow.

Keywords: abomasum, immunohistochemistry, prenatal development, red deer

Introduction

The present study should be seen in the context of a wide-ranging investigation into the development of the stomach of ruminants (Franco et al. 1989, 1992, 1993a,b,c; Regodón et al. 1996), and it completes a series of investigations on the prenatal development of the stomach in red deer (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005). The abomasum is the fourth and final gastric compartment of the stomach in ruminants. Broken-down food particles gradually pass to the abomasum, where they are subjected to the usual digestive juices. The main function of the abomasum is the acid hydrolysis of microbial and dietary protein, preparing these protein sources for further digestion and absorption in the small intestine. This is achieved via gastric juices secreted in the abomasum. This secretion is maintained by the continuous passage of food through the abomasum, a close correlation existing between the amount of food that arrives the abomasum and the acid secretion. At birth, the abomasum is the largest compartment of the ruminant stomach, and the diet of ruminant neonates – milk – is similar to that of the adult omnivore and carnivore. With increasing age, the ruminant gradually increases its intake of roughage, and the forestomach grows rapidly to reach adult proportions at about 6–12 months of age. As in the omasum, the abomasum contains many folds to increase its surface area. These folds enable the abomasum to be in contact with the large amounts of food passing through it daily. In the prenatal development of the stomach in red deer, the differentiation of the abomasum takes place at 67 days. The differentiation of the rumen occurs slightly earlier, around the 60th day of gestation.

The present study on the histological organization of the abomasum of deer during prenatal development is as a continuation of earlier work carried out on the development of the rumen, reticulum and omasum of red deer during intrauterine life (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005).

The objectives of this study were: (1) to provide a sequential description of the histology of the abomasum, from the differentiation of the primitive stomach to the gastric compartmentation in perinatal stages; (2) to describe the histochemical reaction towards the neutral and acidic mucopolysaccharides of the abomasal epithelial layer during prenatal development; (3) to analyse morphometrically the evolution of the integral layers of the abomasal wall during embryogenesis; (4) to immunodetect the reaction of the abomasal wall of red deer in embryonic development towards neuroendocrine cell markers [non-neuron enolase (NNE)], glial cell markers [glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin (VIM)] and markers of peptidergic innervation [neuropeptide Y (NPY) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)]; and (5) to determine the distribution of gastrin cells in the abomasum. The presence of these cells was related to the evolution of plasma gastrin concentration during development.

Materials and methods

Animals

Deer embryos and fetuses (n = 25) from the initial prenatal stages until birth were studied. The specimens were divided into five groups of five animals each, with reference to the most relevant histomorphogenic characteristics (Table 1). These histomorphogenic characteristics were as follows: group I [1.4–3.6 cm crown-rump length (CRL); 30–60 days of gestation], where the stomach was still a single cavity; group II (4.5–7.2 cm CRL, 67–90 days of gestation), in which the abomasum had begun its differentiation from the primitive gastric tube; group III (8–19 cm CRL, 97–135 days of gestation), where the abomasum showed a single cylindrical epithelium and primordial peak areas of the abomasal folds; group IV (21–33 cm CRL, 142–191 days of gestation), in which the epithelium was already displaying characteristics of glandular structure and gastrin-immunoreactive cells had begun to appear; and group V (36–40 cm CRL, 205–235 days of gestation), where the abomasum had a similar structure to the postnatal abomasum. To obtain embryos and fetuses at various stages of development, a total of 125 laparotomies on the same number of dead females were performed. The females were hunted in legal shootings in ten hunting grounds from extensive and non-enclosed-type estates from the Sierra of San Pedro (to the north-east of the province of Cáceres, Spain).

Table 1.

Neuropeptides present in the abomasum of red deer during prenatal development

| Group I CRL (cm) (1.4–3.6) 30–60 days | Group II CRL (cm) (4.5–7.2) 67–90 days | Group III CRL (cm) (8–19) 97–135 days | Group IV CRL (cm) (21–33) 142–191 days | Group V CRL (cm) (36–40) 205–235 days | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | LP-S | TM | S | E | LP-S | TM | S | E | LP-S | TM | S | E | LP-S | TM | S | E | LP-S | TM | S | |

| NNE | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | ++ | ++ | – | – | +++ | +++ | – | – | +++ | +++ | – |

| GFAP | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | ++ | ++ | + | – | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| VIM | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | ++ | ++ | + | – | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| VIP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ++ | ++ | + | – | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| NPY | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ++ | ++ | + | – | ++ | ++ | ++ |

–, Non immunoreactivity; +, low immunoreactivity; ++, moderate immunoreactivity; +++, high immunoreactivity.

E = epithelium, Lp-S = lamina propria-submucosa, TM = tunica muscularis, S = serosa.

Sampling and processing

Once the abomasum had been separated, it was analysed by visual and stereomicroscopic inspection. The colouring of the abomasal mucosa was determined. Small pieces of tissue were dissected from the cardiac region (just caudal to the omasoabomasal orifice) and from the fundic and pyloric regions of the abomasum of each red deer. The tissue for histological study was fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde for 24 h, processed by conventional paraffin embedding methods, and 5-µm-thick sections were cut in transverse direction and treated with: haematoxylin and eosin (H-E); Periodic Acid-Schiff (pH 7.2) and PAS-alcian blue (pH 7.2) for specific differentiation of neutral and acid mucopolysaccharides; Mayer's mucicarmin (MM), Von Giesson (VG); Masson's trichrome (MT) and Reticuline of Gomori (RG).

Morphometric analysis

Specimens for morphometric analysis were embedded in paraffin, stained with H-E, and viewed through a microscope (Optiphot, Nikon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a video camera. The image was reflected onto the screen of a semi-automatic image analyser (Vid IV, Rego and Cía, Madrid, Spain). The variables studied were height of various tissue strata (epithelium, lamina propria and submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa) and total wall thickness. Eight specimens (sections) were selected for each group, and 50 measurements were made for each tissue stratum and specimen.

The results are shown as the mean ± SE. The data were analysed using analysis of variance. In cases where the anova was significant, a post-hoc (Tukey) analysis was carried out in order to study the significant differences among the distinct groups. A value of P = 0.05 was considered significant.

Tissue growth models were created, using a personal computer and statistics program (Statgraphics V 2.1, 1986). The graphs in Figs 4–8 represent the averages of the real growth values next to the adjusted line of regression. The quality of fit of this adjustment was measured using the rate of determination, r2. In all cases, embryo body length (CRL, cm) was used as the independent variable; the thickness of each tissue stratum served as the dependent variable.

Fig. 4.

Mathematical model of abomasum growth (epithelium).

Fig. 8.

Mathematical model of abomasum wall growth.

Fig. 5.

Mathematical model of abomasum growth (lamina propria and submucosa).

Fig. 6.

Mathematical model of abomasum growth (tunica muscularis).

Fig. 7.

Mathematical model of abomasum growth (serosa).

Immunocytochemical analysis

ExtrAvidin Peroxidase Staining (EAS) was performed on deparaffinized sections from the abomasum to detect the neuroendocrine cells markers (NNE), glial cells markers (GFAP and VIM), and markers of peptidergic innervation (NPY and VIP).

Tissue was deparaffinized, hydrated and treated sequentially with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min in order to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Non-specific tissue binding sites were blocked by incubation in 1% normal goat serum for 30 min. Samples were incubated with the following dilution in PBS of primary antisera: 1 : 200 monoclonal anti-human NNE; 1 : 400 monoclonal anti-human GFAP; 1 : 20 monoclonal anti-human VIM; 1 : 200 monoclonal anti-human NPY; 1 : 20 monoclonal anti-human VIP and 1 : 1000 anti-human gastrin I antibody produced in rabbit for 3 h at 20 °C. Biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (1 : 200 dilution) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 200 dilution) for gastrin detection was then added to the sections for 30 min. Sections were finally incubated with diluted (1 : 50) ExtrAvidin-Horseradish Peroxidase for 1 h (antibodies and conjugates from Sigma/Aldrich Química, Madrid, Spain). After diaminobenzidine reaction, nuclear counterstaining with Mayer's haematoxylin was applied. Finally, the sections were mounted with Entellan (Merck 7961).

The specificity of the staining reaction was determined in control experiments: namely substitution of the primary antibody by PBS or normal mouse serum 1 : 100, or omission of both primary and secondary antibodies, and prior absorption of the primary antibody (overnight preincubation of the primary antisera with the respective peptide 50–100 µm). Next, the antibody/peptide mixture was applied to sections in the same way and with the same concentration of the primary antibody.

Radioimmunoassay

Twenty blood samples (four from each age group) were taken for measurement of plasma gastrin concentration. The blood samples, obtained by venipuncture of the umbilical vein (groups I, II and III) or of the jugular vein (groups IV and V), were centrifuged at 2250 g for 6 min. Serum samples collected were stored at –20 °C and examined by the radioimmunoassay method. Analysis was carried out on a Beckmann 1801 liquid scintillation counter, following the method of Avila et al. (1989). The antibody used was 125I-gastrin (Human Synthetic Gastrin) (DAKO A/S, Spain, no. GA-400). This antibody recognizes the C-terminal end of gastrins larger than the pentapeptides (gastrins 17 and 34) and was used at a final concentration of 1 : 6 × 105 m. Values (mean ± SE) are expressed in pg mL−1. This assay is capable of detecting gastrin concentrations as low as 2 pg mL−1 and has inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation of 7.8 and 1.2, respectively.

Results

Macroscopic findings

The differentiation of the abomasum as an individual compartment from the primitive stomach took place at 67 days of gestation. From this point, the surface of the abomasum, which was previously smooth, began to display a series of small undulations, representing the first outlines of the abomasal folds. These folds, not numerous in this initial phase, increased not only in number but also in height and width as the abomasum developed.

At 97 days of intrauterine life the abomasal folds, now more numerous, underwent a dramatic increase in both height and width. They began to display a series of irregularities on the surface; these were the primordial folds of the abomasal peak areas.

The fetuses in group IV displayed a strong growth in height of the abomasal folds at the same time as their thickness decreased, with peak areas covering the surface.

Around birth, the surface of the abomasum exhibited small depressions or gastric pits.

Abomasal histomorphogenesis

Group I (1.4–3.6 cm CRL, 30–60 days, 1–25% of gestation)

All findings described for the rumen, reticulum and omasum (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005) are valid for the abomasum, given that at this stage no differentiation of the abomasal individualized compartment from the primitive gastric tube had taken place (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Photomicrograph of a transverse section of (a) the undifferentiated stomach at 1.4 cm CRL, 30 days. The wall consisted of two layers: epithelium (e) and pluripotential blastemic tissue (pbt). H-E, × 250. (b) Abomasal wall at 4.5 cm CRL, 67 days. Epithelium (e), basal membrane (b), pluripotential blastemic tissue (pbt) and serosa (s) were visible. The primitive folds of the abomasum (af) can be seen. VG, × 180. (c) Abomasal wall at 4.5 cm CRL, 67 days. The epithelial layer (e) was pseudoestratified. Pluripotential blastemic tissue (pbt), tunica muscularis (tm) and serosa (s) were also observed. MT, × 250. (d) Abomasal wall at 7.2 cm CRL. Differentiation of the lamina propria and submucosa (lp + sb) was observed. A fine layer of smooth fibres protruded into the folds, forming the primitive muscularis mucosae (mm). The presence of abomasal folds (af), epithelium (e), basal membrane (b) and tunica muscularis (tm) can also be seen. H-E, × 180. (e) Abomasal wall at 8 cm CRL, 97 days. Epithelium (e), lamina propria and submucosa (lp + sb), muscularis mucosae (mm), tunica muscularis (tm) and abomasal folds (af) can be seen. H-E, × 180. (f) Abomasal wall at 19 cm CRL, 135 days. Epithelial layer (e) and lamina propria-submucosa (lp-sb) are observable. Note the presence of gastric pits (gp). H-E, × 350.

Group II (4.5–7.2 cm CRL, 67–90 days, 25–35% of gestation)

Histodifferentiation of the abomasum took place at 67 days of prenatal development. The wall of the abomasum (285 ± 10 µm), previously smooth, displayed a series of small undulations (the primitive folds of the abomasum) (Fig. 1b,c). There were three layers: the epithelial layer, pluripotential blastemic tissue and serosa.

The epithelial layer (49 ± 4 µm) was pseudostratified, and showed an anuclear basal cytoplasmic area and apical layer formed by the nucleous of the cells (Fig. 1b,c). The abomasal folds increased in size and number as the abomasum developed.

The pluripotential blastemic tissue (204 ± 10 µm), separated from the epithelium by a clearly defined basal membrane, is formed by a large quantity of mesenquimatous cells and extracellular matrix. This tissue participated in the make up of the primitive abomasal folds, in infiltrating towards the epithelium and putting pressure on the basal zone. The intense vascularization of the pluripotential blastemic tissue, together with the presence of a large quantity of fibroblastic cells, collagen, elastic and mainly reticulin fibres, marked the beginning of its differentiation in the lamina propria and submucosa. This occurred at 90 days (35% of gestation).

We also saw the differentiation of the tunica muscularis at 67 days of prenatal development (25% of gestation) (Fig. 1c). At 90 days of gestation, it was composed of two layers of myoblasts: an internal circular layer, and an external and thinner longitudinal layer. This primitive tunica muscularis demonstrated a series of undulations coinciding with the implantation base of each fold. At 90 days of prenatal development, a fine layer of smooth fibres protruded into the folds. These myoblastic fibres, originating in the internal circular bundle of the tunica muscularis, formed the muscularis mucosae (Fig. 1d).

The serosa (32 ± 6 µm) was formed by a subserosa that showed intense vascularization covered by a mesothelium (Fig. 1c).

Group III (8–19 cm CRL, 97–135 days, 35–50% of gestation)

At this stage of development, the thickness of the abomasal wall was 244 ± 18 µm. The wall of the abomasum was made up of four well-defined layers: mucosa, lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa (Fig. 1e). The mucosa was formed by the epithelial layer and lamina propria. At 97 days of gestation (35%), a single cylindrical epithelial layer lined the abomasal lumen.

At 97 days of intrauterine life the abomasal folds, now more numerous, underwent a distinct increase in both height and width. A series of bumps began to appear on the surface: these were the primordial peak areas of the abomasal folds (Fig. 1e). At 135 days (50% of gestation) the space separating abomasal areas was much greater, giving rise to the formation of gastric pits in the spaces between them (Fig. 1f). At the bottom of these pits the first outlines of glands could be clearly distinguished.

The epithelial layer of the mucosa (41 ± 3 µm) was a simple mucous cubic to columnar shape, with nuclei arranged along the basal or medial area of the cells, creating a surface band of light-staining cytoplasm (Fig. 1f).

The lamina propria and the submucosa (96 ± 5 µm) were formed by connective mesenchymatous tissue with a large amount of fibroblasts and blood vessels and a small amount of ground substance (Fig. 1f).

The tunica muscularis (Fig. 1e), with its external longitudinal and internal circular fascicules, was 77 ± 5 µm thick. An oblique layer of smooth muscle inside the circular layer could also be observed. The muscularis mucosae was much more clearly defined, consisting of 2–3 layers of smooth muscle fibres originating from the internal circular bundle and protruding into the greater folds (Fig. 1e).

The external serosa (30 ± 5 µm) was similar to that described in the previous group.

Group IV (21–33 cm CRL, 142–191 days, 50–70% of gestation)

The fetuses in group IV showed a strong increase in the height of the abomasal folds at the same time as their thickness decreased. Therefore, these folds appear very extended and upholstered by abomasal areas on their entire surface. In general the abomasal wall (229 ± 14 µm) displayed a constitution similar to that of the previous stage with some histological variations in the epithelial layer (39 ± 4 µm). The epithelium already displayed characteristics of glandular structure. Following the division of the folds, initiated in the previous stage, the surface was covered by a typical glandular epithelium (single cylindrical mucous epithelium), formed by elongated cells with their nucleus located in the basal area (Fig. 2a). The gastric glands, by contrast, appeared well defined, comprising cellular groupings around a central light (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph of a transverse section of the abomasal wall at (a) 21 cm CRL, 142 days. The epithelial layer (e) was a single cylindrical mucous epithelium. H-E, × 250. (b) 21 cm CRL, 142 days. Gastric glands. PAS, × 250. (c) 33 cm CRL, 191 days. Epithelium (e), lamina propria-submucosa (lp-sb) and tunica muscularis (tm) are observable. H-E, × 180. (d) 36 cm CRL, 205 days. Epithelial layer (e), lamina propria-submucosa (lp-sb) and tunica muscularis (tm) can be seen. H-E, × 180. (e) 36 cm CRL, 205 days. Note gastric glands. PAS, × 250. (f) 40 cm CRL, 235 days. All the layers are visible. Epithelium (e), lamina propria-submucosa (lp-sb), tunica muscularis (tm) and serosa (s) can be seen. H-E, × 180.

The lamina propria-submucosa (86 ± 6 µm), as in the previous stage, displayed greater vascularization (Fig. 2c).

The serosa (25 ± 4 µm) had a lax subserosa and intense vascularization. The mesothelial lining was clearly visible and well defined.

Group V (36–40 cm CRL, 205–235 days, 75–100% of gestation)

The wall of the abomasum showed four layers: mucosa, lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa (Fig. 2d–f). The thickness of the abomasal wall was 208 ± 29 µm. Small depressions of gastric pits were observed in the mucosal surface of the abomasum. These pits were lined with a high cylindrical epithelium (25 ± 3 µm), consisting of high prismatic cells or surface mucosal cells. No morphological differences were observed between these cells and the deep mucosal cells situated more deeply in the gastric pits. The epithelial lining of the pits had the same cell composition throughout the abomasal mucosa.

The tunica muscularis (71 ± 4 µm) was formed by clearly defined bundles arranged in the manner commonly found in the digestive system as a whole. The almost total disapperance of pluripotential blastemic tissue from the interfibrillar space led to disruption of the previous continuity of the tunica muscularis with the subserosa.

The lamina propria-submucosa (89 ± 5 µm) and the serosa (23 ± 6 µm) did not show significant variation with respect to the previous group.

Histochemical detection of mucopolysaccharides of the epithelium

Histochemical reactions to the neutral mucopolysaccharides, mucins and mucinous compounds were observed in the epithelium from 97 days of gestation. Acid mucopolysaccharides were not found during development.

Immunohistochemical observation

Gastrin-immunoreactive cells (Fig. 3a) were observed at 142 days of prenatal development (50% of gestation) in the mucosa of the abomasum. The number of positive cells increased during development (Fig. 3b).

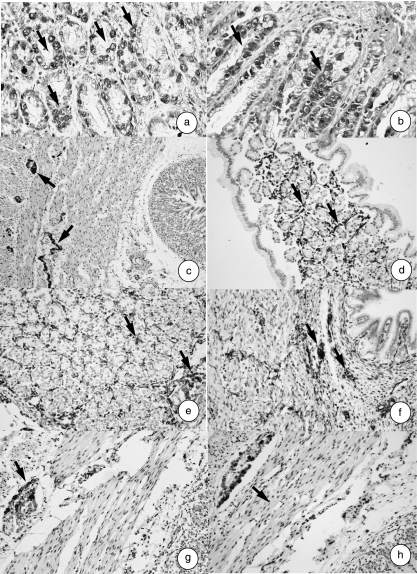

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph of a transverse direction section of the abomasal wall at (a) 21 cm CRL, 142 days. Gastrin-immunopositive cells (arrows) are seen. EAS, × 350. (b) 40 cm CRL, 235 days. Note gastrin-immunopositive cells (arrows). EAS, × 350. (c) 8 cm CRL, 97 days. Note presence of neuroendocrine cells (NNE) in the tunica muscularis (arrows). EAS, × 180. (d) 36 cm CRL, 205 days. Note presence of neuroendocrine cells (NNE) in the lamina propria-submucosa (arrows). EAS, × 250. (e) 33 cm CRL, 191 days. Note presence of GFAP-positive cells (arrows) in lamina propria and submucosa. EAS, × 250. (f) 33 cm CRL, 191 days. Note presence of vimentin-positive cells (arrows) in lamina propria and submucosa. EAS, × 250. (g) 36 cm CRL, 205 days. Note presence of VIP-positive cells (arrows) in tunica muscularis. EAS, × 250. (h) 40 cm CRL, 235 days. Note presence of NPY-positive cells (arrows) in tunica muscularis. EAS, × 250.

Table 1 shows the neuropeptides present in the abomasum of red deer during prenatal development. Immunohistochemical findings in the abomasum of the five groups of red deer studied are summarized in Fig. 3(c–h).

The presence of neuroendocrine cells NNE+ (Fig. 3c,d) was observed from 67 days of gestation, located in the lamina propria-submucosa and in the tunica muscularis. Immunoreactivity toward these cells increased throughout abomasal development.

The immunodetection of positive glial cells (GFAP) (Fig. 3e) and VIM (Fig. 3f) began at 67 days of intrauterine life in the lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa. In the stages around birth, immunoreactivity was very intense.

The detection of neuropeptides VIP (Fig. 3g) and NPY (Fig. 3h) in nerve fibres and in nerve cell bodies began at 142 days of prenatal development, with a moderate immunopositivity in the lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa. This immunoreactivity was similar in the perinatal stages.

Histomorphometric observations

Table 2 gives the tissue layer thickness in the abomasum of red deer during prenatal development. Each tissue stratum was fitted to mathematical growth models (Figs 4–8), using the corresponding growth equation.

Table 2.

Morphometrical and statistical findings of the tissue layer thickness in the abomasum of red deer during prenatal development (µm)

| Group I CRL (cm) (1.4–3.6) 30–60 days | Group II CRL (cm) (4.5–7.2) 67–90 days | Group III CRL (cm) (8–19) 97–135 days | Group IV CRL (cm) (21–33) 142–191 days | Group V CRL (cm) (36–40) 205–235 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelium | 62 ± 5 | 49 ± 4a | 41 ± 3a | 39 ± 4a | 25 ± 3a |

| Lp + Sb | pbt | pbt | 96 ± 5 | 86 ± 6b | 89 ± 5b |

| Tm | 195 ± 10* | 204 ± 10* | 77 ± 5 | 79 ± 2 | 71 ± 4cd |

| Serosa | 56 ± 3 | 32 ± 6e | 30 ± 5e | 25 ± 4e | 23 ± 6e |

| Wall | 313 ± 16 | 285 ± 10f | 244 ± 18f | 229 ± 14f | 208 ± 29f |

Lp + Sb = lamina propria and submucosa, Tm = tunica muscularis, pbt = pluripotential blastemic tissue.

The pluripotential blastic tissue of groups I and II, which will later give rise to the lamina propria and submucosa, were not statistically compared due to the fact that one structure will give rise to several others.

P = 0.0002 vs. group I.

P = 0.01 vs. group III.

P = 0.02 vs. group III.

P = 0.03 vs. group III.

P = 0.0002 vs. group I.

P = 0.002 vs. group I.

The epithelial layer decreased progressively in thickness throughout abomasal histogenesis, in such a way that the thickness of the epithelium in group I was significantly greater than that in groups II–V (F = 12.36; Tukey test, P = 0.0002).

The pluripotential blastemic tissue, after initially increasing, decreased in thickness because of the differentiation of laminapropria-submucosa and tunica muscularis.

As indicated by main factor analysis in factorial anova, the lamina propria and submucosa of group III were significantly larger than in groups IV and V (F = 8.90; Tukey test, P = 0.01). There were no significant differences between groups IV and V.

The tunica muscularis presented significant differences between groups III and V (F = 8.70; Tukey test, P = 0.02) and between groups IV and V (F = 9.45; Tukey test, P = 0.03), but without significant differences between groups III and IV.

By contrast, serosa decreased in thickness throughout prenatal life. The mean value of the serosa of group I was significantly greater than in groups II–V (F = 10.20; Tukey test, P = 0.0002). No significant differences between the thickness of the serosa of groups II, III, IV and V were found.

The thickness of the abomasal wall decreased gradually throughout prenatal development, until it reached its minimum thickness in the perinatal stages. The thickness of the wall in group I was significantly greater than that in groups II–V (F = 9.90; Tukey test, P = 0.002).

Radioimmunoassay results

Table 3 gives the plasma gastrin levels of red deer during development. Detection of gastrin began at 19 cm CRL (135 days of gestation).

Table 3.

Plasma gastrin concentrations in red deer during prenatal development

| Group | I, II, III | III | IV | V | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRL (cm) | < 15 | 19 | 21 | 25 | 29 | 33 | 36 | 40 |

| Values (pg mL−1) | – | 37 ± 4 | 48 ± 4 | 52 ± 5 | 59 ± 5 | 63 ± 6 | 81 ± 7 | 93 ± 8 |

Discussion

In the organogenesis of the primitive gastric tube of red deer, the differentiation of the abomasum took place at 67 days (4.5 cm CRL, 25% of gestation), forming a three-layered structure consisting of an epithelial layer, pluripotential blastemic tissue and serosa. In comparison with ruminal differentiation in red deer (Franco et al. 2004a), abomasal differentiation occurred later. In sheep, abomasal differentiation was observed by Franco et al. (1993a) at 33 days of embryonic development (22% of gestation). In the organogenesis of goat, Mutoh & Wakuri (1989) specified that the primordial abomasum appears at 28 days (19% of gestation). Vivo et al. (1990) and Vivo & Robina (1991), in cow, placed abomasal differentiation at 30 days of prenatal development (11% of gestation).

The wall of the abomasum displayed a series of small undulations (the primitive folds of the abomasum) that increased in size and number as the abomasum developed. The epithelial layer was pseudostratified, and had an anuclear basal cytoplasmic area and an apical nuclear layer. At 97 days of prenatal development (35% of gestation), the epithelium starts to display characteristics of glandular structure. At 50% of gestation, the entire abomasal surface was covered by a single mucous cylindrical epithelium, which resulted in a decrease in height of the epithelial lamina. This important modification has been reported in sheep at 43% of gestation (Del Rio Ortega, 1973; Franco et al. 1993a) and 63% of gestation (Fath-El Bab et al. 1983). In calves it has been observed at 32% of gestation (Asari et al. 1981) and 27% of gestation (Vivo et al. 1990).

At this early stage of development, 67 days (25% of gestation), the first evidence was observed of incipient abomasal folds, which later allowed the expansion of the gastric mucosa. Folds began to increase in size and number by 97 days of prenatal development (35% of gestation), and abomasal areas were observed on the fold surface, giving rise to a substantial increase in epithelial surface area. In sheep, Franco et al. (1993a) reported the first appearance of abomasal folds at 22% of gestation, Del Rio Ortega (1973) at 24%, Fath-El Bab et al. (1983) at 40% and Molinari & Jorquera (1988), in goats, at 46%. These authors reported the first apperance of abomasal areas at 35, 41, 40 and 46% of gestation, respectively. In the cow, Vivo et al. (1990) observed the first abomasal folds at 36–38 days of prenatal development (14% of gestation) and the abomasal areas at 52–57 days (20% of gestation).

At 135 days (50% of gestation), gastric pits were observed in the spaces between abomasal areas. At the bottom of these pits the first outlines of glands were clearly distinguishable, comprising cellular groupings around a central light. There is some disagreement regarding the initial apperance of gastric pits and glands. In studies of sheep, Franco et al. (1993a) reported pits and glands at 46% of gestation. Del Rio Ortega (1973) reported pits at 46% of gestation and glands at 62% of gestation, while Fath-El Bab et al. (1983) observed them at 62 and 90% of gestation, respectively. Molinari & Jorquera (1988) reported pits at 46% and glands at 69% of gestation in goat embryos.

In the red deer, at 90 days of prenatal development (35% of gestation), the tunica muscularis was composed of two layers of myoblasts: an internal circular layer and another external and thinner longitudinal layer. Myoblastic fibres, originating in the circular internal bundle of the tunica muscularis, protruded into the folds and formed the muscularis mucosae. This has also been reported by other authors during prenatal life in sheep; Del Rio Ortega (1973) and Franco et al. (1993a) placed it at 50 days (33%) of gestation, while Fath-El Bab et al. (1983) placed it at 62% of gestation.

The histodifferentiation of the lamina propria and submucosa of the abomasum displayed patterns of behaviour similar to those referenced for the rumen, reticulum and omasum of red deer (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005).

The differentiation of the serosa did not show characteristics distinct from those described in the prenatal development of the forestomach of red deer (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005).

The abomasal mucosa of red deer, from 97 days of intrauterine life, displayed full secretory capacity of neutral mucopolysaccharides, mucins and mucinous compounds, in agreement with earlier findings (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005) for the rumen, reticulum and omasum of this species.

Gastrin-immunoreactive cells first appeared in the abomasum at 142 days of prenatal development (50% of gestation), and the number of positive cells increased during development. These results are in accordance with the findings of Franco et al. (1993d), who observed gastrin-positive cells in the abomasum of sheep from 77 days of prenatal development (50% of gestation). The presence of gastrin cells in the abomasum has been reported by Calingasan et al. (1984) in sheep and Kitamura et al. (1985) in cow; they are also in agreement with the results reported by Agungpriyono et al. (2000), who studied the stomach of babirusa. Plasma gastrin concentrations were first detected at 135 days, increasing gastrin levels being observed during the development stages until birth. Franco et al. (1993d) described plasma gastrin detection (progressive increase) from 69 days of gestation in sheep (46% of gestation). References to plasma gastrin concentrations during prenatal life in sheep have been contributed by other authors (Shulkes et al. 1981; Avila et al. 1989). As in the case of the number of gastrin-immunoreactive cells, plasma gastrin concentrations increased throughout prenatal life, the fetal stomach being the main source of gastrin (Shulkes et al. 1981;Franco et al. 1993d).

The presence of neuroendocrine cells in the abomasal mucosa of deer in development was not detected until 67 days of prenatal development. These cells were located in the lamina propria-submucosa and tunica muscularis. Similar opinions were reported by Kitamura et al. (1986, 1993), in rumen and reticulum of cattle, by Groenewald (1994) in the forestomach of sheep, and in the rumen, reticulum and omasum of red deer (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005).

The abomasal mucosa from 67 days of intrauterine life displayed immunoreactivity towards GFAP and VIM at the level of the lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa. The presence of glial cells in the submucosal and myenteric plexus and submucosa were also reported by Yamamoto et al. (1994) in sheep, by Teixeira et al. (1998) in cows, and by Franco et al. (2004a,b) and Redondo et al. (2005) in red deer.

In agreement with what has been noted for the prenatal development of forestomach of red deer (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005), the detection of the neuropeptides VIP and NPY began at 142 days with moderate immunopositivity in the lamina propria-submucosa, tunica muscularis and serosa. This immunoreactivity remained unchanged until the end of gestation. The presence of the neuropeptides VIP and NPY has previously been described in the omasum of adult sheep (Yamamoto et al. 1994) and in the omasum of adult cattle (Kitamura et al. 1987). Immunoreactivity towards VIP and NPY has also been reported in the rumen, reticulum and omasum of cattle, in the reticulum of sheep from 90 days of prenatal development (Pospieszny, 1979), in ovine perinatal and postnatal stages (Vergara-Esteras et al. 1990; Groenewald, 1994), and in the stomach of the fetal pig (Van Ginneken et al. 1996).

Because this study was performed in a non-supplemented extensive system, and the domestic ruminants that we used as comparative reference habitually receive food supplements, future studies in food-supplemented herds would have to be contemplated to establish comparative references with domestic ruminants.

We can deduce from our findings that, in terms of the prenatal structure of the abomasum of red deer, as has been seen in the rumen, reticulum and omasum (Franco et al. 2004a,b; Redondo et al. 2005), red deer are less precocious than small and large domestic ruminants. Thus, its secretory capacity, detected by the presence of neutral mucopolysaccharides and its neuroendocrine nature, and determined by the presence of positive NNE cells, and of neuropeptides of nerve fibres and nerve cell bodies (VIP and NPY), was more evident in the more advanced stages of prenatal development than in the sheep, goat and cow.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from Consejería de Infraestructura y Desarrollo Tecnológico of Junta de Extremadura (Project no. 3PR05B028). We wish to express our thanks to Mr Juan L. Rodríguez Cruz (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Extremadura), Mrs Mª Mercedes Carrasco Toral and Mrs Juana Ollero Granados (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Servicio Extremeño de Salud) for their skilful technical assistance and contributions.

References

- Agungpriyono S, Macdonald A, Leus KYG, et al. Immunohistochemical study on the distribution of endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract of the babirusa, Babyrousa babyrussa (Suidae) Anat Histol Embryol. 2000;29:173. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0264.2000.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asari M, Fukaya K, Yamamoto M, Eguchi Y, Kano Y. Developmental changes in the inner surface structure of the bovine abomasum. Jpn J Vet Sci. 1981;43:211–220. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.43.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila CG, Harding R, Young IR, Robinson PM. The role of gastrin in the development of the gastrointestinal tract in fetal sheep. Quant J Exp Phys. 1989;74:169–180. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1989.sp003253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calingasan MY, Kitamura N, Yamada J, Yamashita T. Immunocytochemical study of the gastroenteropancreatic endocrine cells of the sheep. Acta Anat. 1984;118:171–180. doi: 10.1159/000145840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio Ortega S. Desarrollo prenatal del estómago de la oveja. Zaragoza: Facultad de Veterinaria; 1973. Doctoral thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Fath-El Bab MR, Schwarz R, Ali AM. Micromorphological studies on the stomach of sheep during prenatal life. Anat Histol Embryol. 1983;12:139–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1983.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Vivo JM, Guillén MT, Regodón S, Robina A. Evolución parietal del retículo ovino de raza merina desde los 68 días de gestación hasta el nacimiento. Histol Med. 1989;5:57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Regodón S, Robina A, Redondo E. Histomorphometric analysis of the rumen of the sheep during development. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:1209–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Robina A, Guillén MT, Mayoral AI, Redondo E. Histomorphometric analysis of the abomasum of sheep during development. Ann Anat. 1993a;175:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0940-9602(11)80164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Robina A, Regodón S, Vivo JM, Masot AJ, Redondo E. Histomorphometric analysis of the omasum of sheep during development. Am J Vet Res. 1993b;54:1221–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Robina A, Regodón S, Vivo JM, Masot AJ, Redondo E. Histomorphometric analysis of the reticulum of the sheep during development. Histol Histopathol. 1993c;8:547–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Regodón S, Gázquez A, Masot AJ, Redondo E. Ontogeny and distribution of gastrin cells in the gastrointestinal tract of sheep. Eur J Histochem. 1993d;37:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Masot AJ, Gómez L, Redondo E. Morphometric and immunohistochemical study of the rumen of red deer during prenatal development. J Anat. 2004a;204:501–513. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Redondo E, Masot AJ. Morphometric and immunohistochemical study of the reticulum of red deer during prenatal development. J Anat. 2004b;205:277–289. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald HB. Neuropeptides in the myenteric ganglia and nerve fibres of the forestomach and abomasum of grey, white and black karakul lambs. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1994;61:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura N, Yamada J, Calingasan MY, Yamashita T. Histologic and immunocytochemical study of endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract of the cow and calf. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:1381–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura N, Yamada J, Yamashita T. Immunohistochemical study on the distribution of neuron-specific enolase- and peptide-containing nerves in the reticulorumen and the reticular groove of cattle. J Comp Neurol. 1986;248:223–234. doi: 10.1002/cne.902480205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura N, Yamada J, Yamashita T. Immunohistochemical study on the distribution of neuron-specific enolase- and peptide-containing nerves in the omasum of cattle. J Comp Neurol. 1987;256:590–599. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura N, Yamada J, Yamamoto Y, Yamashita T. Substance P-immunoreactive neurons of the bovine forestomach mucosa: their presumptive role in a sensory mechanism. Arch Histol Cytol. 1993;56:399–410. doi: 10.1679/aohc.56.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari E, Jorquera B. Intrauterine development stages of the gastric compartments of the goat (Capra hircus. Anat Histol Embryol. 1988;17:121–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1988.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutoh K, Wakuri H. Early organogenesis of the caprine stomach. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1989;51:474–484. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.51.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospieszny N. Distribution of the vagus nerve of the stomach and certain lymph nodes of the sheep in the prenatal period (author's transl) Anat Anz. 1979;146:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo E, Franco AJ, Masot AJ. Morphometric and immunohistochemical study of the omasum of red deer during prenatal development. J Anat. 2005;206:543–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regodón S, Franco A, Masot AJ, Redondo E. Comparative ontogenic analysis of the epithelium of the non-glandular stomach compartments of merino sheep. Anat Histol Embriol. 1996;25:233–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1996.tb00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulkes A, Chick P, Hardy KJ. Development and regulation of gastrin and acid secretion in the chonically cannulated ovine fetus. Proc. Aust Physiol Pharmacol Society. 1981;12:88. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira AF, Wedel T, Krammer MJ, Kuhnel W. Structural differences of the enteric nervous system in the cattle forestomach revealed by whole mount immunohistochemistry. Anat Anz. 1998;180:393–400. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(98)80099-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ginneken C, Weyns A, van Meir F, Ooms L, Verhofstad A. Intrinsic innervation of the stomach of the fetal pig: an immunohistochemical study of VIP-immunoreactive nerve fibres and cell bodies. Anat Histol Embryol. 1996;25:269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1996.tb00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Esteras P, Harrison FA, Brown D. The localization of somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the alimentary tract of the sheep with observations of the effect of an infection with the parasite Haemonchus contortus. Exp Physiol. 1990;75:779–789. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1990.sp003460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivo JM, Robina A, Regodón S, Guillén MT, Franco A, Mayoral AI. Histogenetic evolution of bovine gastric compartments during prenatal period. Histol Histopathol. 1990;5:461–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivo JM, Robina A. The development of the bovine stomach: morphologic and morphometric analysis. II. Observations of the morphogenesis associated with the omasum and abomasum. Anat Histol Embryol. 1991;20:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1991.tb00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kitamura N, Yamada J, Yamashita T. Immunohistochemical study of the distributions of the peptide and catecholamine-containing nerves in the omasum of the sheep. Acta Anat. 1994;149:104–110. doi: 10.1159/000147564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]