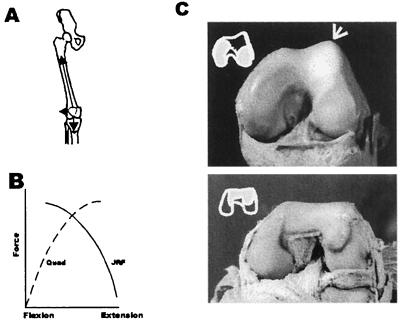

Figure 2.

The human knee exhibits specialized features that can be directly attributed to its role in upright walking. These include a bicondylar angle [the knee angle that places the foot beneath the trunk’s center of mass (A)], an elevated lateral condylar lip [which counteracts the tendency for patellar dislocation by the quadriceps (C Upper)], and elliptically shaped femoral condyles [which increase cartilage contact in full extension during the primary periods of ground contact]. In addition, human knees are tibial dominant (C Upper) whereas those of quadrupedal primates are patellar dominant (C Lower). The latter features require more explanation. The patella is lodged within the quadriceps, which is the principal extensor of the knee (A). When the knee is in flexion, a large component of extensor force compresses the patella against the femur. The resultant stress is determined by the congruity of the two mated surfaces. However, in extension, knee extensor force (plus body mass) generates compression between the femur and tibia; in this position, their area of contact determines joint stress (These relationships are graphed in B). Primates have a great range of motion in the knee. Therefore, unlike many other mammals, there is a significant part of their distal femoral surface that must contact the patella during flexion and the tibia in extension. The shape of this “shared” region (C) differs radically in chimpanzee and human distal femora. In chimpanzees (C Lower and Inset), it is simple and mirror images the discoid surface of the patella (not shown). In the human (C Upper and Inset), it instead conforms to the shapes of the medial and lateral tibial condyles (as deepened by their respective menisci). There is also a dramatic anteroposterior elongation of the human lateral condyle (not shown). This increases the area of cartilage contact in the last 20 degrees or less of knee extension [the chimpanzee’s is circular and does not reflect any single joint position of increased cartilage contact]. The chimpanzee knee is clearly patellar dominant whereas the human knee is tibial dominant. Given the plasticity of developing joint cartilage, all of these individual morphological differences could have been elicited by elongating the presumptive prechondrogenic condylar mesenchyme (especially that of the lateral condyle) by a few cell diameters. This, in conjunction with a habitual bipedal gait (which generates continuously high levels of tibiofemoral force in full extension), can account for virtually all of these unique human characters. What at first appears to be a profusion of separate traits more probably reflects a profoundly simpler change in the pattern formation field of the human femur.