Abstract

Shifts in flower symmetry have occurred frequently during the diversification of angiosperms, and it is thought that such shifts play important roles in plant–pollinator interactions. In the model developmental system Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon), the closely related genes CYCLOIDEA (CYC) and DICHOTOMA (DICH) are needed for the development of zygomorphic flowers and the determination of adaxial (dorsal) identity of floral organs, including adaxial stamen abortion and asymmetry of adaxial petals. However, it is not known whether these genes played a role in the divergence of species differing in flower morphology and pollination mode. We compared A. majus with a close relative, Mohavea confertiflora (desert ghost flower), which differs from Antirrhinum in corolla (petal) symmetry and pollination mode. In addition, Mohavea has undergone a homeotic-like transformation in stamen number relative to Antirrhinum, aborting the lateral and adaxial stamens during flower development. Here we show that the patterns of expression of CYC and DICH orthologs have shifted in concert with changes in floral morphology. Specifically, lateral stamen abortion in Mohavea is correlated with an expansion of CYC and DICH expression, and internal symmetry of Mohavea adaxial petals is correlated with a reduction in DICH expression during petal differentiation. We propose that changes in the pattern of CYC and DICH expression have contributed to the derived flower morphology of Mohavea and may reflect adaptations to a pollination strategy resulting from a mimetic relationship, linking the genetic basis for morphological evolution to the ecological context in which the morphology arose.

Keywords: evolution of development, floral evolution, Mohavea, Antirrhinum, CYCLOIDEA/DICHOTOMA

Much of extant flower diversity results from evolutionary changes in the shape and number of floral organs, but how such transitions have occurred during angiosperm evolution remains enigmatic. Developmental evolutionary biology aims to uncover the developmental and genetic mechanisms that result in morphological differences between species and to understand the evolutionary forces contributing to the origin of morphological novelties. One promising approach is to study closely related species to determine whether they differ in the expression of genes that, based on studies in model systems, could explain phenotypic differences between the species (1, 2). We focus here on the model system snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) and the desert ghost flower (Mohavea confertiflora), two closely related species that show marked differences in flower development and morphology. In particular, we focus on the evolutionary transition in stamen number and petal morphology and explore the hypothesis that these shifts involve changes in the expression of floral symmetry genes.

All species of Antirrhinum, including the model species A. majus (snapdragon), produce flowers that are strongly bilaterally symmetrical (zygomorphic) (Fig. 1b) with distinct adaxial (dorsal), lateral, and abaxial (ventral) petals; they produce four mature stamens per flower because of the abortion of the fifth, adaxial stamen primordium during flower development (Fig. 1 d and f). Contributing to strong bilateral symmetry, the adaxial and lateral petals are internally asymmetrical with different patterns of growth occurring on either side of the midline (Fig. 1h). The two species of Mohavea have a floral morphology that is highly divergent from Antirrhinum (3), resulting in its traditional segregation as a distinct genus. Mohavea corollas, especially those of M. confertiflora, are superficially radially symmetrical (actinomorphic), mainly due to distal expansion of the corolla lobes (Fig. 1a) and a higher degree of internal petal symmetry relative to Antirrhinum (Fig. 1 a and g). During Mohavea flower development, the lateral stamens, in addition to the adaxial stamen, are aborted, resulting in just two stamens at flower maturity (Fig. 1 c and e). Nonetheless, contradicting the traditional taxonomy, molecular phylogenetic data indicate that Mohavea is nested within a tetraploid North American clade of Antirrhinum. Thus, Mohavea's divergent floral morphology is derived from one similar to that of A. majus (Fig. 2; R. K. Oyama and D.A.B., unpublished data).

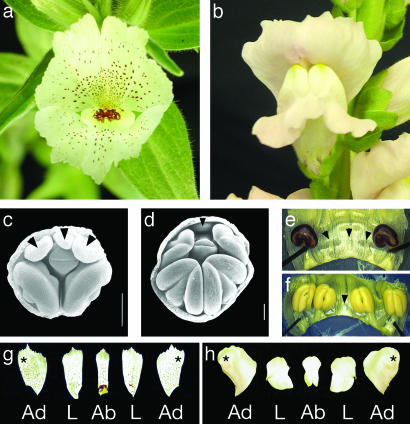

Fig. 1.

(a) Mohavea confertiflora flower morphology showing superficial radial symmetry. (b) Antirrhinum majus flower morphology showing clear bilateral symmetry. (c) SEM of M. confertiflora early-stage flower with adaxial and lateral stamen primordia indicated. (d) SEM of A. majus early-stage flower with adaxial stamen primordium indicated (arrowheads). In c and d, petal and sepal tissues have been removed. (e) Dissected M. confertiflora flower showing aborted adaxial and lateral staminodes (arrowheads). (f) Dissected early stage A. majus flower showing aborted adaxial staminode (arrowhead). (g and h) Adaxial (Ad), lateral (L), and abaxial (Ab) petal lobes dissected from M. confertiflora and A. majus, respectively. M. confertiflora petal lobes show a higher degree of internal petal symmetry (g) when compared with A. majus petal lobes (h). Asterisks indicate the half of each adaxial petal that is adjacent to the medial line of corolla symmetry. Arrowheads indicate position of aborted stamens. (Scale bars, 0.2 mm.) M. confertiflora and A. majus SEMs courtesy of Peter K. Endress. [Reproduced with permission from ref. 3 (Copyright 1998, Society for Experimental Biology).]

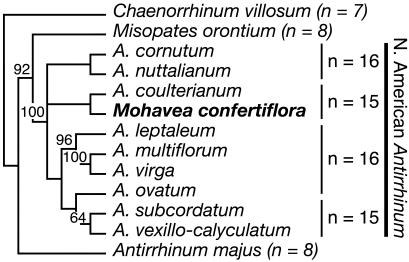

Fig. 2.

Maximum likelihood estimate of relationships among Antirrhinum taxa and Mohavea. Mohavea is nested within the tetraploid clade of North American Antirrhinum. The tree is rooted with CYC and DICH sequences from Chaenorrhinum villosum. Maximum parsimony bootstrap values >50% are indicated above nodes. Ploidy levels are indicated to the right of taxa.

In A. majus, the genes CYCLOIDEA (AmCYC) and DICHOTOMA (AmDICH) determine adaxial identity of floral organs (4, 5). dich mutants display a mildly abaxialized phenotype with modifications to adaxial petal morphology and a wild-type pattern of stamen abortion. cyc mutants produce flowers that are strongly abaxialized and lack stamen abortion. Thus, partially symmetrical flowers develop in plants that carry mutations in either AmCYC or AmDICH, but the severity of this phenotype differs between the loci. Both AmCYC and AmDICH are necessary to determine adaxial flower identity, because cyc dich double mutants form fully abaxialized, radially symmetrical flowers lacking stamen abortion. The timing and localization of AmCYC and AmDICH expression is correlated with the mutant phenotypes. AmCYC is expressed across adaxial petals and in the adaxial staminode (aborted stamen), consistent with its expression being necessary for stamen abortion (5) (Fig. 3). AmDICH is also expressed in the adaxial staminode, but its expression in the adaxial petals is restricted to the inner half of each adaxial petal, the half closest to the medial line of flower symmetry (4) (Figs. 1h and 3). Because dich mutants produce more symmetrical adaxial petal lobes than wild type (4), the asymmetrical expression of AmDICH across the petals is thought to cause the internal asymmetry of adaxial petals (4), perhaps through a differential regulation of growth direction (6).

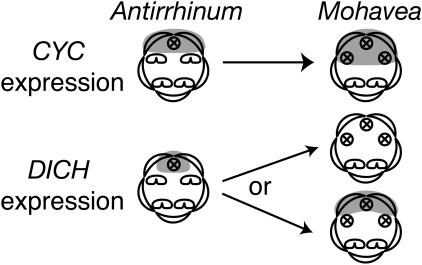

Fig. 3.

CYC in A. majus is expressed across the adaxial petals and in the aborted adaxial staminode. This pattern of CYC expression determines adaxial petal identity and adaxial stamen abortion (5). Hypothesized expression in Mohavea is expanded such that the aborted lateral stamen primordia are also in the domain of CYC expression. DICH expression in the A. majus corolla is restricted to the inner half of each adaxial petal, the half closest to the medial line of symmetry. DICH expression in this domain results in internal asymmetry of dorsal petal lobes (4), putatively through differential regulation of growth direction (6). The hypothesized expression of DICH in Mohavea is either an expansion or a reduction across adaxial petals, correlating with the higher degree of internal symmetry observed in Mohavea dorsal petals. An expansion or reduction in DICH expression in Mohavea may result in more uniform growth directionality.

AmCYC and AmDICH are closely related members of the TCP (TB1, CYC, and PCFs) family of transcription factors, many of which influence meristem and primordium growth (7). Given that natural variation at TCP loci has been implicated in differences in floral form (8–11), and that their expression is necessary for stamen abortion and petal asymmetry in snapdragon (4, 5), we considered CYC and DICH to be ideal candidate genes for the evolution of floral novelties that distinguish Mohavea from Antirrhinum flowers. We hypothesized that lateral stamen abortion during Mohavea flower development is due to an expansion of CYC and/or DICH homologs into the lateral staminodes and that the higher degree of internal petal symmetry in Mohavea adaxial petals is due to expansion or contraction of DICH expression, leading to uniform expression across these petals (Fig. 3).

Materials and Methods

Cloning of CYC and DICH Orthologs and Phylogenetic Analysis. PCR was used to amplify, clone, and sequence CYC and DICH orthologs from genomic DNA of Antrirrhinum cornutum, Antrirrhinum coulterianum, Antrirrhinum leptaleum, Antrirrhinum multiflorum, Antrirrhinum nuttalianum, Antrirrhinum ovatum, Antrirrhinum subcordatum, Antrirrhinum vexillocalyculatum, Antrirrhinum virga, and Mohavea confertiflora according to published methods (12). An additional forward primer, 5′-CACATACCTACATCTCCCTCAGG-3′, was used. The sequences reported here have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos.: A. cornutum, AF512687, AF512697, AF512716, and AF512706; A. coulterianum, AF512688, AF512698, AF512717, and AF512707; A. leptaleum, AF512689 and AF512708; A. multiflorum, AF512690, AF512699, AF512718, and AF512709; A. nuttalianum, AF512691, AF512700, AF512719, and AF512710; A. ovatum, AF512692, AF512701, AF512720, and AF512711; A. subcordatum, AF512693, AF512702, AF512721, and AF512712; A. vexillo-calyculatum, AF512695, AF512704, AF512722, and AF512714; A. virga, AF512694, AF512703, and AF512713; and M. confertiflora, AF512696, AF512705, AF512723, and AF512715). CYC and DICH sequences were aligned manually with reference to both nucleotide and hypothetical amino acid information.

To evaluate gene orthology, we conducted phylogenetic analysis of the isolated genes and published CYC and DICH sequences from A. majus (Y16313 and AF199465, respectively), Chaenorrhinum villosum (AF512601 and AF512591), and Misopates orontium (AF512600 and AF512594). CYC and DICH sequences were combined into a single matrix and analyzed together. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted by using paup*4.0b1 (16). We estimated the maximum likelihood tree by using a random taxon addition sequence, tree bisection reconnection heuristic search under the general time-reversible model of evolution with a discrete gamma model, allowing for four categories of rate variation among sites (13, 14). Maximum parsimony bootstrap support for nodes (15) was estimated with 1,000 heuristic search replicates, random taxon addition, and the Tree Bisection and Reconnection branch-swapping algorithm.

RNA in Situ Hybridization. RNA in situ hybridization was performed according to described methods (17) with the following modifications: tissue fixation in FAA (50% EtOH/10% formalin/5% acetic acid/0.1% DMSO), probes were alkaline hydrolyzed to 400 bp, and, after signal development, tissues were counterstained with Calcofluor (0.002%). Digoxygenin-labeled probes of McCYC1, McCYC2, McDICH1, and McDICH2 were prepared from linearized templates cloned into pCR4 plasmid (Invitrogen). RNA probes were gene-specific and included the coding region sequenced for each locus; this region corresponded to ≈94% and 95% of the coding sequence for CYC and DICH loci, respectively.

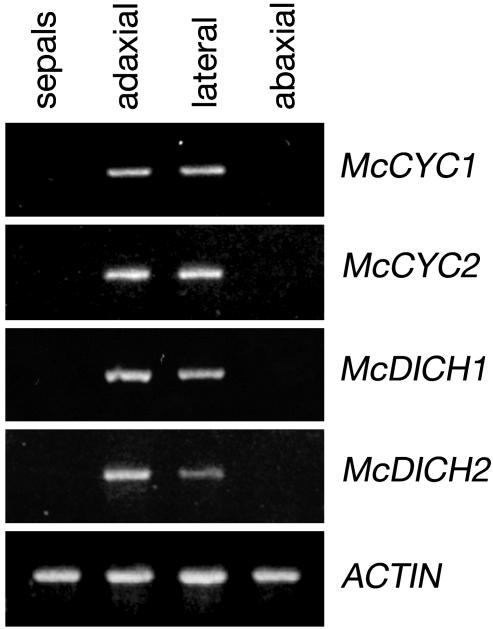

RT-PCR. Tissues used for RT-PCR consisted of floral organs dissected from relatively late-stage M. confertiflora flowers in which petal and stamen primordia had undergone a high degree of differentiation (Fig. 1e). Sepals were removed from the outer whorl. The corolla tube and petal lobes, including the attached abaxial stamens and lateral and adaxial staminodes of 110 flowers, were dissected into abaxial, lateral, and adaxial regions. Total RNA was extracted (18) from the tissues of the three corolla plus stamen/staminode regions and from the sepal tissues for RT-PCR experiments. RT-PCR was performed as described (18) by using locus-specific primers: McCYC1 (forward 5′-GCTGCTACTTCGGTGGTC-3′, reverse 5′-AATGCCTCACGAGTACCC-3′), McCYC2 (forward 5′-GCCGCTACGTCTGTTGTT-3′, reverse 5′-AACGCCTCGCGATTACCT-3′), McDICH1 (forward 5′-CACGACGTGATTTCCGAG-3′, reverse 5′-GGACAGCGGTGAGTTTGC-3′) and McDICH2 (forward 5′-CATGACGTGATTTCCGGC-3′, reverse 5′-CTTCATAATTAGTTGAGGGAC-3′). Primers that amplify actin were used as a positive control (19). RT-PCR products were cloned, and between 5 and 12 clones from each RT-PCR were sequenced to confirm locus-specificity.

Results

To test our hypothesis that lateral stamen abortion and internal petal symmetry in Mohavea are due to changes in the regulation of CYC and/or DICH homologs during flower development (Fig. 3), the CYC and DICH orthologs of M. confertiflora were cloned and sequenced. As with other CYC and DICH homologs, these sequences lacked introns in the coding regions. Phylogenetic analysis of the resultant sequences confirmed that two CYC loci (McCYC1 and McCYC2) and two DICH loci (McDICH1 and McDICH2) were isolated (data not shown). This result is expected because Mohavea is tetraploid relative to A. majus (ref. 20; Fig. 2). Apart from six to eight triplet in-frame indels, McCYC and McDICH loci share ≈94.4% and 92.0% nucleotide identity with AmCYC and AmDICH, respectively. RNA in situ hybridization and locus-specific RT-PCR were used to determine the spatial and temporal patterns of McCYC and McDICH gene expression in M. confertiflora.

RNA in situ hybridization in M. confertiflora revealed that McCYC1 and McCYC2 expression patterns are indistinguishable across all observed stages of flower development (Fig. 4 a–d and data not shown). Expression is first detected before the initiation of organ primordia, with RNA concentrated in the adaxial region of early floral meristems (Fig. 4a). Once sepal, petal, and stamen primordia have initiated, McCYC1 and McCYC2 expression differ markedly from that of AmCYC. McCYC1 and McCYC2 expression becomes concentrated in regions of the developing lateral and adaxial stamen primordia (Fig. 4 b and c). The expression in adaxial petals of M. confertiflora (Fig. 4 b and c) is similar to that observed for AmCYC (4). Therefore, it is specifically McCYC expression in lateral stamen primordia that differs from CYC expression in A. majus, correlating perfectly with the additional stamen abortion seen during Mohavea flower development.

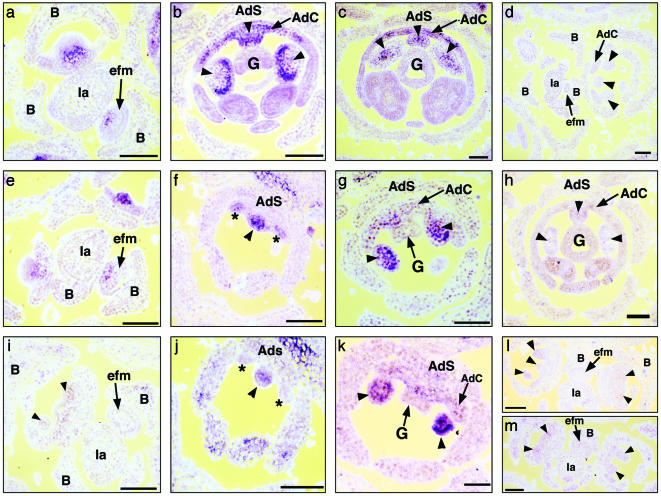

Fig. 4.

Observed patterns of mRNA in situ hybridization in developing M. confertiflora flower meristems. (a–c) McCYC1 antisense probe hybridized to M. confertiflora early through later stage flowers. (a) Transverse section through inflorescence; McCYC1 expression is detected in the adaxial region of early floral meristems. (b and c) Transverse sections through mid-stage (b) and later stage (c) flowers; McCYC1 expression is detected in adaxial and lateral staminodes and across the adaxial corolla. McCYC2 expression patterns are identical to those of McCYC1 across all observed stages of flower development (data not shown). (d) McCYC1 sense probe hybridized to M. confertiflora flowers. (e–h) McDICH1 antisense probe hybridized to M. confertiflora early through later stage flowers. (e) Transverse section through inflorescence; McDICH1 expression is detected in the adaxial region of early floral meristems. (f) Oblique section through early stage flower; McDICH1 expression is detected in the adaxial staminode and the adaxial petal primordia. (g) Oblique section through mid-stage flower; McDICH1 expression is detected in the lateral staminodes but not in the adaxial petals. (h) Transverse section through later stage flower; McDICH1 expression is not detected. (i–k) McDICH2 antisense probe hybridized to M. confertiflora early through mid-stage flowers. (i) Transverse section through inflorescence; McDICH2 expression is not detected in early floral meristems. (j) Oblique section through early stage flower; McDICH2 expression is detected in the adaxial staminode but not in the adaxial petal primordia. (k) Oblique section through mid-stage flower; McDICH2 expression is detected in the lateral staminodes but not in the adaxial petals. (l and m) McDICH1 and McDICH2 sense probes, respectively, hybridized to M. confertiflora flowers. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) Arrowheads indicate position of adaxial and lateral staminodes; asterisks indicate position of adaxial petal primordia; B, bract; Ia, inflorescence axis; efm, early floral meristem; G, gynoecium; AdS, adaxial sepal; AdC, adaxial corolla.

McDICH1 and McDICH2 differ in the timing of their expression. Transcripts of McDICH1 first accumulate in the adaxial region of early floral meristems (Fig. 4e) in a similar pattern to McCYC, AmCYC, and AmDICH. In contrast, multiple hybridizations of McDICH2 probed to similar stage flowers did not detect expression (Fig. 4i). After the initiation of sepal, petal, and stamen primordia, McDICH1 and McDICH2 are expressed in adaxial and lateral stamen primordia (Figs. 4 f, g, j, and k), with expression declining in later stages (Fig. 4h; data for McDICH2 not shown). McDICH1 and McDICH2 expression differs markedly from AmDICH expression (4), and correlates with additional stamen abortion during Mohavea flower development.

In the corolla, McDICH1 (Fig. 4f), but not McDICH2 (Fig. 4j), is expressed in initiating petal primordia. However, neither McDICH1 nor McDICH2 expression is detected in petals during mid (Fig. 4 g and k) and later stages (Fig. 4h; data not shown for McDICH2, but similar to McDICH1, Fig. 4h) of flower development when petals undergo differentiation. This finding is significantly different from A. majus developing petals, where AmDICH is expressed in the inner region of each adaxial petal through petal differentiation, resulting in internal petal asymmetry (4). The lack of McDICH expression in M. confertiflora petal lobes by using in situ hybridization correlates with the higher degree of internal petal symmetry observed in Mohavea flowers.

Locus-specific RT-PCR results using dissected petal plus stamen/staminode tissue from relatively late-stage flowers that have undergone a high degree of differentiation (Fig. 1e) are in line with the observed in situ expression patterns. Expression of McCYC1, McCYC2, McDICH1, and McDICH2 is observed in adaxial and lateral regions of dissected corolla plus staminode tissue (Fig. 5). By using in situ hybridization, expression of McDICH1 and McDICH2 was not detected during later stages of flower development. This discrepancy between the RT-PCR and in situ hybridization results likely reflects a higher sensitivity of RT-PCR to low levels of gene expression in later-stage flowers. The similarity in RT-PCR for McCYC1 relative to McCYC2, and McDICH1 relative to McDICH2, suggests that the similar patterns observed with in situ hybridization for the paralogous McCYC and McDICH loci are not entirely due to probe cross-reactivity.

Fig. 5.

Gene-specific RT-PCRs on RNA prepared from dissected M. confertiflora flower buds. Adaxial, lateral, and abaxial corolla and connate (attached) stamens were dissected from later stage buds (Fig. 1e). Sepal tissue was used as a negative control of CYC and DICH expression. Actin primers were used as a positive control. Locus specificity was confirmed by sequence analysis of RT-PCR products.

Discussion

McCYC and McDICH expression in M. confertiflora fits the hypothesis that changes in the regulation of these flower-symmetry genes played a causal role in morphological evolution. Most notably, expression of McCYC and McDICH in lateral stamen primordia is correlated with their abortion during Mohavea flower development. Changes in DICH expression may correlate with differences in corolla morphology between A. majus and M. confertiflora. Unlike in A. majus, where medially restricted AmDICH expression in the adaxial petals results in petal-lobe asymmetry (4), in situ hybridization did not detect McDICH expression in Mohavea adaxial corollas at stages when petals undergo differentiation. However, the RT-PCR results show that McDICH1 and McDICH2 are expressed in the adaxial and lateral regions of later-stage flowers at levels that are apparently too low to be detected by in situ hybridization. Given that in situ hybridization shows McDICH1 and McDICH2 expression in staminodes but not petals at midstages of development (Fig. 4 g and k), the RT-PCR results likely reflect low levels of McDICH expression in the adaxial and lateral staminodes in late-stage flowers. If McDICH is expressed in the medial region of adaxial petals at low levels, then the higher degree of internal adaxial petal symmetry in Mohavea may be due to the decrease in McDICH expression or to changes in downstream genes involved in cell division and expansion. In any case, alterations to the DICH pathway affecting adaxial petal morphology in Mohavea were likely only a single component of multiple evolutionary modifications to gene function and/or expression that resulted in the superficially actinomorphic appearance of Mohavea corollas.

Although the data do not allow identification of the specific mutations responsible for the derived flower morphology of Mohavea, they suggest that the effects of these mutations were partially mediated through the developmental control of adaxial flower identity, specifically, changes in the expression of the adaxial identity genes CYC and DICH. In the petal whorl, potential reduction in McDICH expression across adaxial petals may have evolved through cis- or trans-regulatory modifications. Because both McCYC and McDICH genes are expressed in Mohavea lateral stamen primordia, it is possible that changes in the cis-regulatory sequences of McCYC1, McCYC2, McDICH1, and McDICH2 have resulted in their expanded expression. However, this explanation would require four separate cis-regulatory changes. More parsimoniously, changes in the expression domain of an upstream regulator in the CYC/DICH pathway may be responsible for alterations in McCYC/McDICH expression in the stamen whorl of the Mohavea lineage.

The cyc mutant phenotype in A. majus was described by Carpenter and Coen (26) as homeotic in nature, in that the adaxial regions of flowers took on abaxial identity. Although homeotic mutations are generally studied within individual species, it has become widely accepted that homeotic-like transformations may play an important role in establishing morphological diversity (27–29). Shifts in gene expression correlated with such homeotic-like morphological transformations have been well documented in arthropods (30–33). Lateral stamen abortion in Mohavea can similarly be considered a homeotic-like transformation whereby lateral stamens have acquired adaxial identity, which in this case leads to abortion. We have established a strong correlation between expansion in the expression of the floral symmetry genes CYC and DICH into regions of lateral stamens and the ultimate abortion of these organs. Cubas et al. (9) have elegantly demonstrated that epigenetic mutations at the CYC locus are responsible for radially symmetrical mutants in populations of Linaria vulgaris. Although this phenotype can be considered a homeotic-like transformation, no evidence exists that such phenotypes contribute to interspecific differences in this group. Therefore, the expression of CYC and DICH in Mohavea represents the first clear correlation between changes in gene expression and homeotic-like evolutionary transformations in angiosperms.

Our observations provide direct evidence that major changes in floral morphology between species, including a homeotic-like transformation, are associated with changes in the regulation of floral symmetry gene expression. One critical aspect of this study is that the genetic basis for evolutionary changes in flower form can be linked to the ecological context in which the novel flower morphology arose. It is therefore important to ask whether adaptive significance can be attached to the derived features of Mohavea flowers and, thus, whether natural selection might have played a role in the observed evolutionary changes in CYC and DICH regulation. Whereas most Antirrhinum are specialized for pollination by nectar-foraging bees (21), Mohavea is unusual in being pollinated exclusively by pollen-collecting bees (22, 23). Furthermore, it appears that M. confertiflora is a floral mimic of the distantly related, but co-occurring, Mentzelia involucrata (Loasaceae) (23). M. involucrata flowers have radially symmetrical corollas and provide a large pollen reward to bees (22, 24). These pollen-collecting bees are the only known visitors to M. confertiflora flowers even though they provide minimal pollen reward (22, 23). Selection in Mohavea for mimetic similarity to M. involucrata likely favored mutations that enhance the actinomorphic appearance of the corolla. A component of the genetic changes leading to enhanced actinomorphy likely included the reduction of McDICH expression in the medial part of Mohavea adaxial petals. Likewise, the loss of lateral stamens may also be associated with the shift to pollen-collecting bees. Reduction in Mohavea stamen number is correlated with a change in abaxial anther position and pollen consistency. Together, these changes in stamen number and morphology are likely to reduce pollen loss to grooming after Mohavea flowers are visited by the pollen-collecting bee specialist (25). Although further ecological work is clearly needed (e.g., studies of how pollen-collecting bees respond to actinomorphic vs. zygomorphic flowers and further studies of pollen loss to grooming), it is clear that an integrative approach that bridges ecology, genetics, and development (34) has the potential to greatly improve our understanding of the mechanisms for adaptive evolution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Hudson for help with in situ protocols and Justin Blumenstiel, Colin Meiklejohn, Kristina Niovi Jones, Vivian Irish, and three anonymous reviewers for comments on early versions of this manuscript. Scanning electron microscopy images were kindly provided by Peter Endress. M. confertiflora seeds were kindly provided by the Rancho Santa Anna Botanical Garden seed program. North American Antirrhinum tissues were kindly provided by Ryan Oyama. Fieldcollected bee pollinators were identified as to species by Robbin Thorp. This work was funded by National Science Foundation Grant DEB-9972647 (to D.A.B. and L.C.H.).

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this article have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. AF512687–AF512723).

References

- 1.Baum, D. A. (2002) in Developmental Genetics and Plant Evolution, eds. Cronk, Q. C. B., Bateman, R. M. & Hawkins, J. A. (Taylor and Francis, London), pp. 493–507.

- 2.Haag, E. S. & True, J. R. (2001) Evolution (Lawrence, Kans.) 55 1077–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endress, P. K. (1998) Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 51 133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo, D., Carpenter, R., Copsey, L., Vincent, C., Clark, J. & Coen, E. (1999) Cell 99 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo, D., Carpenter, R., Vincent, C., Copsey, L. & Coen, E. (1996) Nature 383 794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolland-Lagan, A. G., Bangham, J. A. & Coen, E. (2003) Nature 422 161–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cubas, P., Lauter, N., Doebley, J. & Coen, E. (1999) Plant J. 18 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doebley, J. F., Stec, A. & Hubbard, L. (1997) Nature 386 485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cubas, P., Vincent, C. & Coen, E. (1999) Nature 401 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillies, A. C. M., Cubas, P., Coen, E. S. & Abbott, R. J. (2002) in Developmental Genetics and Plant Evolution, eds. Cronk, Q. C. B., Bateman, R. M. & Hawkins, J. A. (Taylor and Francis, London), pp. 233–246.

- 11.Citerne, H. L., Moller, M. & Cronk, Q. C. B. (2000) Ann. Bot. 86 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hileman, L. C. & Baum, D. A. (2003) Mol. Biol. Evol. 20 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang, Z. (1994) J. Mol. Evol. 39 306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang, Z. (1994) J. Mol. Evol. 39 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein, J. (1985) Evolution (Lawrence, Kans.) 39 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swofford, D. L. (2001) paup*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods) (Sinauer, Sunderland, MA), Version 4.0b1.

- 17.Lincoln, C., Long, J., Yamaguchi, J., Serikawa, K. & Hake, S. (1994) Plant Cell 6 1859–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer, E. M., Di Stilio, V. S. & Schluter, P. M. (2003) Int. J. Plant Sci. 164 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad, K., Sriram, P., Kumar, C. S., Kushalappa, K. & Vijayraghavan, U. (2001) Dev. Genes Evol. 211 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutton, D. A. (1988) A Revision of the Tribe Antirrhineae (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford).

- 21.Kampny, C. M. (1995) Bot. Rev. 61 350–366. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snelling, R. R. & Stage, G. I. (1995) Contrib. Sci./Nat. Hist. Museum Los Angeles County 451 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little, R. J. (1983) in Handbook of Experimental Pollination Biology, eds. Jones, C. E. & Little, R. J. (Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York), pp. 294–309.

- 24.Zavortink, T. J. (1972) Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 74 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harder, L. D. & Wilson, W. G. (1997) Acta Hortic. 437 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter, R. & Coen, E. (1990) Genes Dev. 4 1483–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroll, S. B. (1995) Nature 376 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes, C. L. & Kaufman, T. C. (2002) Evol. Dev. 4 459–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browne, W. E. & Patel, N. H. (2000) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Averof, M. & Patel, N. H. (1997) Nature 388 682–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abzhanov, A. & Kaufman, T. C. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126 1121–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abzhanov, A. & Kaufman, T. C. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127 2239–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abzhanov, A. & Kaufman, T. C. (2000) Evol. Dev. 2 271–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Givnish, T. J. (2003) Taxon 53 273–296. [Google Scholar]