Abstract

Summary: Cytoscape enhanced search plugin (ESP) enables searching complex biological networks on multiple attribute fields using logical operators and wildcards. Queries use an intuitive syntax and simple search line interface. ESP is implemented as a Cytoscape plugin and complements existing search functions in the Cytoscape network visualization and analysis software, allowing users to easily identify nodes, edges and subgraphs of interest, even for very large networks.

Availabiity: http://chianti.ucsd.edu/cyto_web/plugins/

Contact: ashkenaz@agri.huji.ac.il

1 INTRODUCTION

Cytoscape is open-source network visualization and analysis software (Shannon et al., 2003). Biological networks in Cytoscape are represented as nodes and edges with associated data attributes. As the size and complexity of available networks rapidly grows, their navigation and interrogation becomes more challenging (Hermjakob et al., 2004; Jayapandian et al., 2007; Xenarios et al., 2002).

In the base Cytoscape implementation, nodes or edges matching a single attribute value-based search can be found using QuickFind. To perform queries for multiple attributes at the same time and to support additional biologically relevant query features, we developed Cytoscape enhanced search plugin (ESP). The intuitive query syntax can specify attribute field restrictions on term searches, Boolean logic operators to search multiple attributes, wildcards anywhere within string values and range queries for numeric and string values. ESP is written in Java using the high performance open-source Lucene information retrieval library (http://lucene.apache.org/).

2 METHODS AND IMPLEMENTATION

When a user issues a query, ESP automatically indexes all network attributes using Lucene and executes the search. To support responsive user querying, the index is maintained as long as the network is not modified. The user can re-index the network, if it is modified, by right clicking on the text box and choosing the option ‘Re-index and search’. To support Java Web Start, the Lucene index is stored in memory.

Lucene treats all attribute field values as strings. To support range queries on numerical attribute fields we transformed numerical values into structured strings using Solr's NumberUtils package (http://lucene.apache.org/solr/) preserving their numerical sorting order. A custom MultiFieldQueryParser is used to parse queries containing numeric values. Attribute fields with string or list values are tokenized with Lucene's StandardAnalyzer.

To accommodate Lucene's constraint of one-word attribute fields, whitespace in attribute names are replaced with underscores during indexing. In a future ESP version, attribute name autocompletion will handle this replacement.

An ESP search generally does not take more than a second, even for very large networks. Indexing time depends on the number of network elements and attributes associated with them. Indexing a small network (331 nodes, 362 edges, 30 attribute fields) took 109 ms, and a large human interactome network, retrieved from MiMI (10 893 nodes, 49 482 edges, 8 attribute fields) took 1765 ms, on a 2.81 GHz AMD Athlon 64 Dual Core processor. Query execution time is affected by the query size and display results time relates to the number of matches. Executing and displaying results of a single-term query took 16 ms in both networks. Wildcard and range queries rewrite to a Boolean query containing all the terms that match the wildcards or reside in the range. Executing and displaying results of the query prot* took 16 ms in the first network and 179 ms in the second network (137 and 5520 matches, respectively).

2.1 Query syntax

A query comprises search terms and operators. Search terms can be a single word such as ‘aquaporin’, or a phrase surrounded by double quotes such as “water channel”. Restricting the search to a specific attribute field is performed by placing the attribute name before the search term, followed by a colon, e.g. ‘compartment: nucleus’. If no attribute field is specified, all attribute fields are searched. Boolean operators (and, or, not) can be used to combine search criteria to help narrow the search. Parentheses may be used to control the Boolean logic of a query or to group multiple search criteria on a single attribute field. Inclusive or exclusive range queries allow matching of values between lower and upper bounds. Single and multiple character wildcard searches are supported. For a complete query syntax list, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of query syntax

| Search criteria | Example |

|---|---|

| Single term | aquaporin |

| Phrase | “water channel” |

| Restrict by attribute field | gene_title: aquaporin |

| Both terms must exist | transcription and factor |

| At least one of the terms must exist | transcription or factor |

| First term must exist but second must not | transcription not factor |

| Specify a required term | +transcription factor |

| Prohibit a term | transcription -factor |

| Single character wildcard | prot?in |

| Multiple character wildcard | HSP* |

| Inclusive range | degree:[1 to 3] |

| Exclusive search | degree:{1 to 3} |

| Control Boolean logic | (intrinsic or integral) and membrane |

| Group terms to a single field | gene_title:(+60S +“ribosomal protein”) |

| Escape special characters | \(1\+1\)\:2 |

Notes: Query elements are case insensitive; wildcard symbols cannot be used as the first character of a search; the NOT operator requires greater than one term; OR is the default operator for joining search terms.

2.2 Example application to plant biology

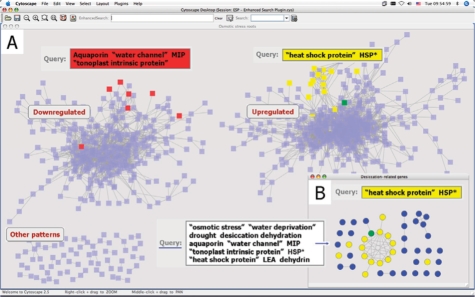

Plants cope with osmotic stress by maintaining water potential homeostasis and preserving the stability of membranes and proteins. Initiation of stress induces changes in gene expression: aquaporins are downregulated (Boursiac et al., 2005), leading to reduction in membrane water permeability, while molecular chaperons such as heat shock proteins (HSPs), late embryogenesis abundant proteins (LEAs) and dehydrins are accumulated (Wang et al., 2003). Additional genes associated with osmotic stress response are annotated with a variety of keywords, like desiccation, dehydration, drought or may have functional annotations such as ‘response to osmotic stress’ or ‘response to water deprivation’. Aquaporins alone have numerous annotations, such as ‘aquaporin’, ‘water channel’ or ‘major intrinsic protein’. We used ESP to explore an expression correlation network based on the AtGenExpress roots osmotic stress dataset (Kilian et al., 2007), in which genes with variable expression across conditions are connected with an edge if the Pearson correlation coefficient of their expression measurements is higher than 0.95. Node attributes are based on Affymetrix ATH1 array annotations. Searching for the obvious keyword ‘aquaporin’ on this network returned just one node. An ESP query containing all possible terms related to this gene family revealed six other family members (Fig. 1A). As expected, all the aquaporins were located in the downregulated gene cluster. A subsequent query showed all HSPs were in the upregulated genes cluster. Next, a network was constructed from all nodes returned by a query composed of keywords and terms associated with osmotic stress response (Fig. 1B). It then became clear that HSPs tend to cluster together, in contrast to the rest of the desiccation-related genes. Interestingly, MBF1c, which enhances plants tolerance to environmental stress (Suzuki et al., 2005) is tightly connected to this group.

Fig. 1.

Gene-expression correlation network during osmotic stress in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. (A) A sample ESP result showing aquaporin family members (red) and HSPs (yellow). (B) HSPs share considerable transcriptional correlations among themselves and with MBF1c (green).

3 CONCLUSIONS

ESP offers an efficient way to retrieve a group of nodes and edges according to multiple search criteria and to navigate complex biological networks. This enhanced search functionality complements and extends the power of network visualization and analysis in the widely used Cytoscape platform. Future ESP versions will be better integrated with Cytoscape, as part of the Filter feature, which will enable intuitive building of complex queries from a set of independently applied simple queries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Michael Smoot, Ethan Cerami, Benjamin Gross and Daniel Abel for useful comments and Alexander Pico for coordinating Google Summer of Code support.

Funding: ESP development was supported in part by the Google Summer of Code program and by grants LM008106 and DA021519 from NIH and grant 953/07 from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF). Cytoscape is supported by grant GM070743-01 from the NIH. Contributions by G.D.B. are supported by Genome Canada via the Ontario Genomics Institute.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Boursiac Y, et al. Early effects of salinity on water transport in Arabidopsis roots. Molecular and cellular features of Aquaporin expression. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:790–805. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.065029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermjakob H, et al. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D452–D455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayapandian M, et al. Michigan molecular interactions (MiMI): putting the jigsaw puzzle together. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D566–D571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian J, et al. The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 2007;50:347–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. Available at http://www.cytoscape.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Suzuki N, et al. Enhanced tolerance to environmental stress in transgenic plants expressing the transcriptional coactivator multiprotein bridging factor 1c. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1313–1322. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, et al. Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta. 2003;218:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xenarios I, et al. DIP, the database of interacting proteins: a research tool for studying cellular networks of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:303–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]