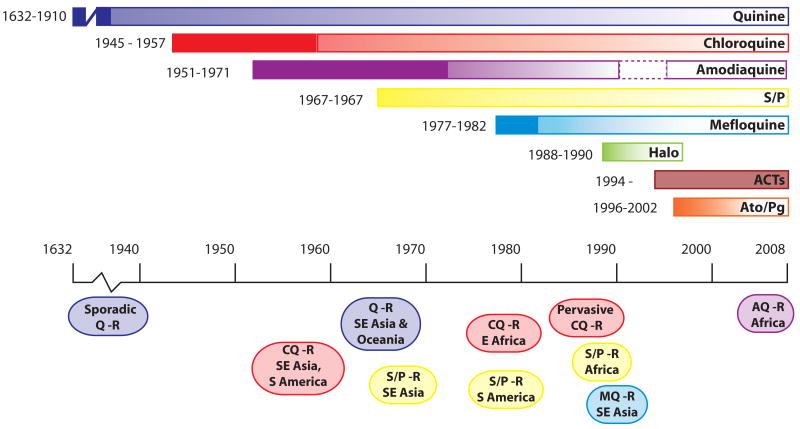

Fig. 1.

Emergence of resistance to the principal antimalarials. Each colored bar represents an antimalarial monotherapy or combination. Years to the left of each bar represent the date the drug was introduced and the first reported instance of resistance. Ovals below the time line denote the approximate periods when resistance spread though different geographical regions. Quinine, chlororoquine and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine remained effective for considerable periods after the first reported instances of resistance. Halofantrine has had limited usage since about 1998 due to cardiotoxicity concerns. Amodiaquine was removed from the list of approved antimalarials in 1990 due to concerns over serious side effects, but was reinstated in 1996 because the perceived benefits outweighed the risks (dashed border). Chemically pure artemisinin (Qinghaosu) and its derivatives were first used in field trials in China in the early 1970s. Artemisinin has a low radical cure rate when used alone in a short course, presumably due to its very short half-life in vivo. Since 1994, artemisinin and its derivatives have been used in combination therapies (ACTs). No clinical resistance to ACTs has yet been demonstrated. Timelines were derived from (Wongsrichanalai et al., 2002; Hyde, 2005; Tinto et al., 2008) and references therein. ACTs: Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies, AQ, amodiaquine; Ato/Pg: Atovaquone/Proguanil, CQ: Chloroquine, Halo: Halofantrine, MQ, mefloquine; Q: Quinine, R: Resistance, S/P: Sulfadoxine/Pyrimethamine.