Abstract

We investigated analogues of GP2 (IISAVVGIL), an HLA-A*0201-restricted T-cell epitope derived from residues 654−662 in the tumor-associated antigen (TAA) Her-2/neu. One limiting factor of GP2 is its poor affinity for HLA-A*0201. Conformational analysis revealed the P5–P7 region in GP2 appears to be linked to the stability of P9 side chain interaction with the MHC molecule. To identify variants of GP2 with enhanced presentation to HLA-A*0201, we tested V6S, V6T, V6Q, G7P, G7F, T6F7, and Q6F7 for their capacity to stabilize cell surface HLA-A*0201 molecules. Of the mono-substituted variants, V6Q and G7F exhibited superior stabilization as compared to GP2. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest the improved binding can be attributed to concerted motions in the central and C-terminal regions of the peptide. These data support the notion that amino acids in HLA-A*0201 epitopes may be inter-dependent. Priming HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice with G7F-loaded syngeneic dendritic cells stimulated mouse T cells to produce a higher level of INFγ than mice immunized with GP2.

Keywords: HLA-A*0201, Tumor vaccine, Altered peptide ligand, Her-2/neu, Molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

The proto-oncogene product Her-2/neu is over-expressed in several tumor types, including ovarian and breast cancers (Slamon et al., 1989). Peptides derived from Her-2/neu can induce CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses (Baxevanis et al., 2005; Disis et al., 1999; Peiper et al., 1997, 1999). IISAVVGIL (denoted GP2), one of several human class I HLA-A*0201-restricted T-cell epitopes identified in Her-2/neu (residues 654−662), is recognized by CD8 lymphocytes infiltrated into malignant breast tissues (Peoples et al., 1995; Yoshino et al., 1994). A limitation of GP2 as a tumor vaccine candidate is its poor affinity for HLA-A*0201 (Rongcun et al., 1999).

Poor MHC binding does not necessarily diminish relevancy of an epitope in the context of tumor vaccination. Selective amino acid replacements in the native sequence can sometime increase antigen presentation and results in more immunogenic peptides. Affinity thresholds of T-cell receptor activation in vitro and/or in vivo may be reached by increasing the number of copies of a given MHC–peptide complex (Abrams and Schlom, 2000; Collins and Frelinger, 1998; Meng and Butterfield, 2002; Meng et al., 2001; Sette et al., 1994a, 1994b; van der Burg et al., 1996), providing that the antigenic surface is recognized by the TAA-reactive T cells. Altered peptide ligands of MART27−35 and gp100206−214 are examples of successful extension of this strategy to the clinic (Bakker et al., 1995; Parkhurst et al., 1996; Rosenberg et al., 1998). With these in mind, the GP2 sequence may be exploited by identifying variants with improved MHC binding because tolerance to sub-dominant epitopes are purported to be less pronounced than dominant epitopes.

Poor binding of GP2 was unexpected because the sequence possesses appropriate amino acids defined by the binding motif of HLA-A*0201: aliphatic hydrophobic side chains at P2 (peptide positions1 are abbreviated as P1, P2, P3, etc.) and P9 (Parker et al., 1994; Ruppert et al., 1993), referred as primary anchors. The X-ray structure of GP2 complexed with HLA-A*0201 provided an explanation for the poor binding: the central region of the peptide (P5 and P6) is flexible and lacks stabilizing contacts with residues in the MHC binding cleft (Kuhns et al., 1999). Substitutions at P2 and P9 anchor positions resulted in marginal or no improvement in binding affinity (Sharma et al., 2001). Substituting the valine at P5 with leucine also did not confer improvement in binding (Sharma et al., 2001).

Herein we describe an effort to explore effects of secondary anchor substitutions in the GP2 sequence guided by molecular dynamics (MD), a computational technique used to simulate conformational motion of peptides in the MHC binding groove (Meng et al., 1997, 2000a, 2000b; Rognan et al., 1994). We characterized a panel of GP2 variants substituted at P6 and/or P7 with respect to binding on HLA-A*0201-expressing cells. MD simulations revealed correlated motions between the P5–P7 backbone and the anchor P9 side chain. G7F, a variant with improved binding was shown to induce GP2-specific T cells in HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Cell line, peptides, and reagents

T2 and JY cells were used to determine the relative strength of the peptides in stabilizing HLA-A2.1 molecules. T2 cells are deficient in the transporter-associated with antigen presentation (TAP) and do not present self-peptides but express “empty” or unstable HLA-A*0201 molecules on the surface (Salter and Cresswell, 1986). The “empty” unstable MHC molecules can be stabilized with addition of exogenous peptides and beta-2 microglobulin (β2m) (Stuber et al., 1994). JY cells express high densities of HLA-A*0201 and were a kind gift of Dr. Lisa Butterfield (University of Pittsburgh). Both cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (Life Technologies). Peptides were custom synthesized from Peptron Inc. (South Korea) or EZBiolab (Westfield, IN) with purity greater than 95%.

2.2. T2 stabilization and JY re-constitution assays

Fluorescein isocyanate-labeled β2m (β2m-FITC) was used as an indicator of peptide binding. Human β2m (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was conjugated with FITC using a labeling kit (Sigma–Aldrich). Reaction products were fractionated using size exclusion columns to remove free FITC molecules and fractions containing β2m-FITC were pooled. Binding of peptides on T2 cells was determined by incubating 5 × 105 cells with peptide (1 μM) and β2m-FITC (1 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37 °C in AIMV Lymphocyte Media (Life Technologies). JY cells (5 × 105) were first exposed to citrate-phosphate buffers (0.131 M citric acid/0.066 M Na2HPO4, pH adjusted to 3.2) prior to adding peptide and β2m-FITC. After extensive washing with cold PBS (0.01% sodium azide) to remove unbound β2m-FITC, cells were analyzed using a Kodak 440 CF Image Station, Beckman Coulter EPICS XL flow cytometer, or a Perkin-Elmer HTS 7000 Bio Assay reader. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA.

2.3. Molecular modeling and dynamics

Model construction and calculations were performed using the AMBER89 force field (Pearlman et al., 1991) in the molecular modeling package molecular operating environment (MOE) version 2001.01 (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Canada) on a Silicon Graphics Indigo2 workstation. Each simulation was performed at least twice.

Structural models of variant peptides complexed to HLA-A*0201 were built using the X-ray structure of IISAVVGIL/HLA-A*0201 (pdb entry: 1 qri) as the template (Kuhns et al., 1999). Only the peptide and α1 and α2 domains of the MHC were included in the calculations. Amino acid substitutions were implemented by replacing the side chain atoms beyond the Cβ atom in the original residue described previously (Meng et al., 2000a, 2000b). The mutated amino acid was subjected to conjugate gradient minimization until the structure reached a root-mean square gradient of 0.01 Å. This was followed by “soaking” the complex to identify water molecules that can be placed at the MHC–peptide interface. The water molecules were minimized before the entire system was allowed to relax. Following the minimizations, only interior water molecules at the MHC–peptide interface were retained. Two water molecules were added in V6Q/HLA-A*0201 and one water was placed in GP2. No water was added at the interface in G7F/HLA-A*0201. The complexes were then carried out for 200 picosecond (ps) of MD simulations using the NVT ensemble at 300 K. Backbone atoms of the MHC molecule were “fixed” in these simulations. Dielectric constant (ε) of 80 was set to simulate the electrostatics of aqueous environment and a 6.5Å non-bonded cut off was used in the calculations. Analysis of the MD trajectories was conducted using the “Conformational Geometries” function and “SVL” routines in MOE.

We have previously determined that in performing MD simulations of class I MHC–peptide complexes, it is necessary to include constraints to maintain conserved hydrogen bonds between the peptide termini and the MHC molecule (Meng et al., 1997, 2000a, 2000b). The interactions at the charged peptide termini are conserved in HLA-A*0201–peptide complexes (Bouvier and Wiley, 1994; Madden et al., 1993) and therefore we do not expect the restrains to interfere with interpretation of the trajectories. A similar type of restrain was used in the current study, with an energy penalty placed for distance deviation between Trp-147 (Cβ) and the carboxyl group of the peptide C-terminal.

2.4. Preparation of dendritic cells and Immunization

DC were differentiated from murine bone marrow progenitor cells following the Inaba method (Inaba et al., 1992) with modifications (Meng et al., 2001; Ribas et al., 1997). Cells were cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% FCS (Life Technologies) and PSF. Non-adherent cells were replated on day 1 at 2 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates with recombinant murine GM-CSF (5 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and murine interleukin-4 (IL-4) (5 ng/ml) (R&D Systems). On day 4, non-adherent cells were removed by aspirating 80−90% of the media, and adherent cells were re-fed with an addition of 1 ml per well of culture medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4. DC were harvested on day 8 as loosely adherent cells then pulsed with 1 μg of GP2 or G7F for 4 h at 37 °C and washed three times with PBS before 105 cells were injected (subcutaneous) into HLAA*0201 transgenic mice (female 6−8 weeks old). Two weeks after immunization splenocytes were harvested and restimulated in vitro with DC pulsed with 0.01−1 μM of GP2. Concentrations of INFγ were determined in the cultural supernatants using the ELISA DuoSet kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer protocol. The sensitivity of the assay was 31.2 pg/ml.

3. Results and discussion

To determine the relative strengths of GP2-derived peptides to class I MHC molecules, we employed strategies developed by Stuber et al. (1994) and Parker et al. (1992): use β2m association with the class I heavy chain to measure HLA-A*0201 stabilization or re-constitution by exogenous peptides. The tri-molecular complex of α-chain, antigenic peptide, and β2m denatures when any one component is absent (Townsend et al., 1989). T2 cells lack transporter-associated with antigen processing (TAP) domain and display unstable HLA-A*0201 molecules (Salter and Cresswell, 1986). Endogenous peptides presented by the lymphoblastoid JY cells (HLA-A*0201+) can be removed with citrate-phosphate buffers (pH 3.2) (Storkus et al., 1993) and class I molecules can be reconstituted with exogenous peptides and β2m.

We employed FITC conjugated β2m as an indicator of peptide binding. This method was validated using varying concentrations of the influenza matrix protein epitope GILGFVFTL (abbreviated herein FLU), an epitope binds to HLA-A*0201 with high affinity (Hogan et al., 1988; Parker et al., 1994; Zweerink et al., 1993). The data show that fluorescence intensity in cells, and thereby β2m-FITC association, is dependent on peptide concentration (Fig. 1a and b). In a representative experiment, FLU induced three-fold higher mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) than the negative control (cells incubated with β2m-FITC without peptide) (Fig. 1b). Cells incubated with FLU can be clearly distinguished from the population without peptide in the presence of β2m-FITC (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Peptide-dependent association of β2m-FITC to HLA-A*0201+ cells. T2 cells were incubated with varying concentrations of Flu58−66 (GILGFVFTL) and 1 μg/ml of β2m-FITC for 2 h at 37 °C. Binding was quantified by measuring fluorescence in aliquots of cell suspensions in FluoroBlok 96-well microplates: (a) image was captured using Kodak Imaging System 440 CF and (b) quantified using NIH ImageJ 1.34 s. Groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA and compared using Tukey's test: FLU *10 μM vs. β2m-FITC only (p < 0.01), **1 μM vs. β2m-FITC only (p < 0.01), ***0.1 μM vs. β2m-FITC only (p < 0.01). (c) Flow cytometry enumeration of β2m-FITC bound T2 cells incubated with (shaded) or without (open) FLU. (d) Flow cytometric analysis of (MFI) of T2 cells exposed to FLU or GP2 in the presence of β2m-FITC. Data shown are averaged from two independent experiments with error bars indicating standard deviation.

Importantly, this assay can discriminate strong and weak binding peptides. Experiments employing flow cytometry or measurement in 96-multiwell FluoroBlok plate with T2 or JY cells showed that GP2 is a poor binder on HLA-A*0201+ cells (Figs. 1d and 2). At equal peptide concentration (1 μM), GP2 stabilized 13−43% of HLA-A*0201 that by FLU (Figs. 1d and 2). With this assay, we set out to characterize variants of GP2 designed with the aim to improve peptide presentation on cell surface.

Fig. 2.

Relative binding strength of GP2 and substituted peptides quantified by capture of β2m-FITC on T2 or JY cells. Samples were transferred into FluoroBlok 96-well plate and measured using a Perkin-Elmer HTS7000 Bio Assay reader (excitation 485/emission 535 nm). Numbers adjacent to bars indicate average fluorescent intensity calculated from independent experiments for the respective peptide. Embedded tables: data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. “ns” indicates no significant difference in binding compared to GP2. n indicates number of replicates. Errors shown are standard error of the mean. (a) Cells washed with citrate-phosphate buffer and incubated with β2m-FITC only. (b) Cells washed with citrate-phosphate buffer. (c) Tested for significance using the Tukey's test.

3.1. Poor binding of GP2 correlates with conformational instability

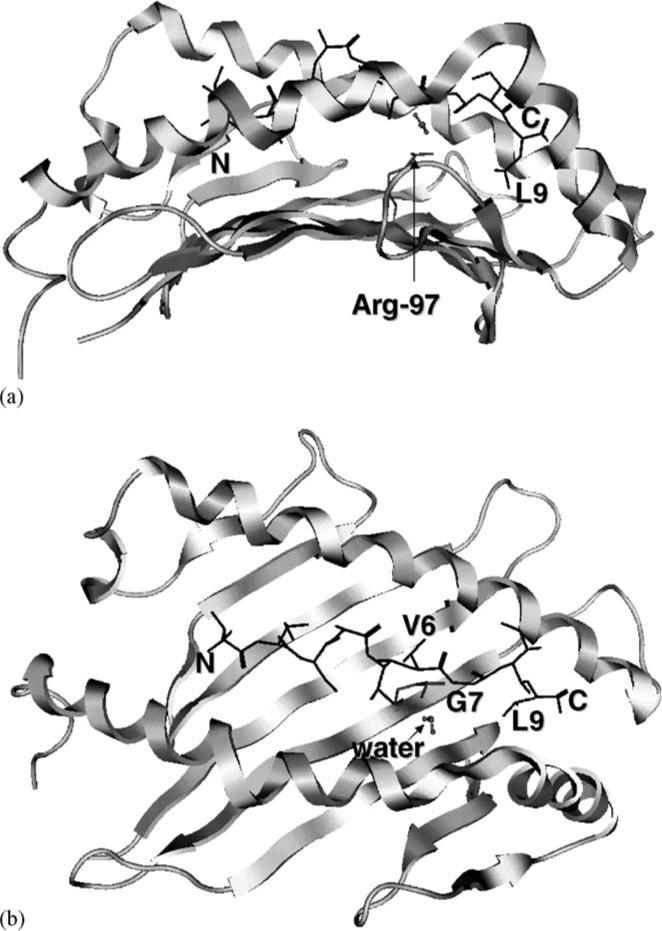

To delineate poor binding of GP2 with respect to interactions with HLA-A*0201, we carried out 200 ps MD simulations at 300 K to probe the conformational landscape of the peptide in the binding groove (α1 and α2 domains) of HLA-A*0201. The initial minimized GP2 structure entering into MD is shown in Fig. 3. The peptide backbone deviated from the initial conformation by an average of 4.5Å in the trajectory (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Minimized structure of GP2 in the HLA-A*0201 binding groove: (a) side view; (b) top view. The peptide N-terminus (labeled “N”) is on the left and the secondary structures of the MHC molecule are shown in ribbon format. The peptide is displayed as dark line with the V6, G7, and L9 residues labeled. Also shown are the Arg-97 and Val-152 side chains and an interior water molecule.

Fig. 4.

Clusters of peptide backbone conformations captured in GP2, V6Q, and G7F MD trajectories. Only heavy atoms are included and the N-terminus is displayed on the left. MHC residues are not shown. Structures represent overlay of 200 frames sampled in the simulation. Models of G7F and V6Q complexed with HLA-A*0201 were generated based on X-ray structure of GP2/HLA-A*0201. “Average RMSD” was calculated from superimposed positions of the peptide Cα atoms in the trajectory.

The lost of GP2 conformation in the MD simulation can be ascribed to motions in two regions of the peptide structure. First, Cα atoms in P5–P7 moved considerably from their initial positions almost immediately (Fig. 5b). RMSD of GP2 in this region (averaged over the entire simulation) was 15.5 Å. This is consistent with the X-ray data reported by Kuhns et al. (1999) indicating that V5 and V6 side chains in GP2 are flexible and contribute to the poor binding to HLA-A*0201. It is apparent that V5 and V6 side chains could not be accommodated in the largely hydrophilic central floor (His-70, His-74, Arg-97, His-114) in the binding groove, nor could they locate favorable interaction with bulk solvent.

Fig. 5.

Time-lapse measurements of conformation and interaction in the MD trajectories of the HLA-A*0201/peptide models. Positional RMSD of (a) P1–P9 Cα atoms, (b) P5–P7 Cα atoms, (c) distance between L9 Cβ and Tyr-116 Cζ atoms in the simulation. Boxed periods (50−100 ps) in (b) and (c) were analyzed for concerted motions between P5–P7 and P9 (see Fig. 8). (d) Psi angle of P6. Angles in V6Q and G7F underwent transition in the period 50−75 ps. Negative values between −160° and −180° were converted to positive values for presentation.

A decisive factor in GP2 association with HLA-A*0201 is the interaction between P9 and the “F” pocket. This pocket preferentially accommodates aliphatic hydrophobic side chains of the C-terminal residue of the peptide, which is utilized by almost all known HLA-A*0201-restricted epitopes. The MD simulation showed that the poor binding of GP2 is related to L9 disengaging from Tyr-116, a residue in the “F” pocket, with their distance increased from close to 6Å to greater than 12 Å (Fig. 5c). Time-lapse events suggest the L9 motion is related (r2 = 0.62) to the deviation of the P5–P7 backbone during the period 50−100 ps (Fig. 8a). During this period, adjustment in P5–P7 may be necessary to preserve L9 contact with Tyr-116.

Fig. 8.

Correlation analysis of P5–P7 and L9/“F” pocket interaction between 50 and 100 ps in the GP2, V6Q, and G7F simulations. X-axis: P5–P7 Cα RMSD. Y-axis: distance between L9 Cβ and Cζ of Tyr-116. Each data point represents RMSD or distance in each frame in the trajectory. r2 represents coefficient of determination.

The propensity of GP2 to deviate from their respective initial conformations in the MD simulations was consistent with the known poor binding activity of this peptide. The conditions employed and observations made in these simulations thus serve as the baseline to evaluate conformational consequences of substitutions in the GP2 sequence.

3.2. Effects of hydrophilic amino acids at position 6

The valine at P6 clearly contributes to the instability of the peptide in the binding groove. We postulate that hydrophilic side chains can be better accommodated in the floor of the binding groove or in bulk solvent. To explore this, three substitutions were tested at P6: serine (V6S), threonine (V6T), and glutamine (V6Q). These side chains each possess hydrogen-bonding donors and acceptors. When tested on JY cells, V6S and V6T exhibited poor binding with near background signal (Fig. 2). V6Q, on the other hand, consistently reconstituted a higher level of HLA-A*0201 than GP2 (p < 0.01, n =9; Fig. 2).

In concordance with the binding activities, V6Q assumed a relatively more stable P5–P7 backbone (average RMSD of 10.2 Å) in the MD trajectory compared to GP2 (Figs. 4 and 5). The Q6 side chain in V6Q is oriented upward, creating a void space at the MHC–peptide interface that can be filled by two water molecules. These waters extend the hydrogen-bonding capacity of Arg-97 to interact with the main chain atoms of P6 (Fig. 6b, c, and e). This is assisted by rotation of the P6 ψ angle from ∼(+)180° to ∼(−)60° (Fig. 5d), resulting in the carbonyl group pointing downward to interact with Arg-97 via water (Fig. 6b). A snapshot at 150 ps showed P6 carbonyl interacting with a water (distance = 2.5 Å) that was bound to NH1 and NH2 of Arg-97 (distances = 3.1 Å). These interactions, we believe, resulted in tethering of the peptide to Arg-97 via P6 in V6Q (average distance = 4.7 Å) throughout the simulation that is absent in GP2 (average distance = 9.9 Å; Fig. 6a, c and d). Similar to GP2, the motions in P5–P7 and L9/“F” pocket in V6Q appeared to be related (r2 = 0.53) during the 50−100 ps segment (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 6.

Contacts developed in V6Q. Potential interactions between P6 carbonyl, water, and the Arg-97 side chain in (a) GP2 and (b) V6Q. Structures represent snapshots of the peptide and Arg-97 at the 150 ps frame. Distance plots (c) between the hydrogen atom of NH1 or NH2 in Arg-97 and carbonyl of P6. Distances between water molecules and Arg-97 (NH1 or NH2) in (d) GP2 (one water) and (e) V6Q (two water molecules).

3.3. Phenylalanine at position 7 enhances binding

A second postulate we tested was that the glycine at P7 contributes to the flexibility in the central part of GP2. To explore this we tested the effects of a proline (G7P) or phenylalanine (G7F) at this position. Placing proline at P7 would impose a high degree of conformational restriction that limits flexibility of the backbone. Placing a phenylalanine at P7 should enhance binding because of the important role of pocket “E” in peptide presentation (Ruppert et al., 1993; Teng and Hogan, 1994). The aromatic side chain of F7 would contact Val-152 and Leu-156 of pocket “E” (Madden et al., 1993).

Binding studies showed consistently that G7F stabilizes at least 10-fold higher (p<0.01, n = 9) fluorescence as compared to GP2 on cells (Fig. 2). G7P, in contrast, binds to HLA-A*0201 at the same level as GP2.

Modeling of G7F in the HLA-A*0201 binding groove indicated that the P5–P7 region is considerably more stable (average RMSD = 3.9 Å) than GP2 (15.5 Å) and V6Q (10.2 Å) (Fig. 5b). As in V6Q, the P6 ψ angle rotated (from ∼(+)120° to ∼(+)60°) in the period 50−75 ps (Fig. 5d) resulted in re-orientation of the P6 carbonyl towards Arg-97 (not shown). Since no water was placed in the MHC–peptide interface by the “soaking” procedure, any P6 and Arg-97 interaction should only be a minor factor because of the long distance. The principal factor is likely that a contact developed between the F7 and Val-152, a residue in the “E” pocket of the binding groove (Fig. 7a). This interaction was maintained for the duration of the simulation (Fig. 7b). These factors, we believe, contributed to securing the contact between the anchoring L9 side chain and the “F” pocket in G7F (Fig. 5c). The area occupied by P5–P7 and L9/“F” pocket is much more limited compared to GP2 or V6Q (Fig. 8c), indicating a concerted stability of the two regions.

Fig. 7.

Contact developed in G7F. (a) Snapshot of overlapping molecular surfaces of F7 and Val-152 side chains at the 50 ps frame. (b) Distance between F7 (Cγ) and Val-152 (Cδ) during the trajectory.

3.4. Double substitutions and inter-dependence of amino acids

Binding studies of the doubly substituted variants T6F7 and Q6F7 indicate the effects at P6 and P7 are non-additive. Neither T6F7 nor Q6F7 exhibited significantly improved binding than G7F (Fig. 2). Furthermore, molecular models of these variants indicate T6F7 and Q6F7 have drastically altered antigenic surface compared to GP2 (data not shown) and therefore are unlikely to be relevant in Her-2/neu T-cell response.

Correlation analysis suggests a degree of coordination between P5–P7 and P9 in GP2 and V6Q. The effect is likely bi-directional: disruption originated from either may affect the other. This linkage appears to diminish when binding is improved, as V6Q and G7F have lower coefficients of determination compared to GP2 (Fig. 8). It should be noted that this analysis tests for linearity only.

3.5. Priming of GP2-specific T cells in vivo with G7F

G7F emerged from the binding and computational studies as a variant that may induce Her-2/neu T-cell response. To determine the capacity of G7F to expand GP2-specific T cells in vivo, HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice were immunized once with syngeneic bone marrow-derived DC loaded with GP2 or G7F. The HLA-A*0201 mice express a chimeric MHC class I molecule consisting of α1 and α2 domains of the human leukocyte antigen and the α3 domain of the mouse H-2Kb (Vitiello et al., 1991). The TCR repertoire in these mice is sufficiently diverse to recognize human HLA-A*0201-restricted epitopes (Sette et al., 1994a, 1994b; Wentworth et al., 1996).

Splenocytes from immunized mice were harvested and assayed for INFγ production after in vitro recall stimulation with GP2-loaded DC. After three rounds of stimulation, G7F-primed splenic cells produced significantly higher levels of INFγ, a Th1 cytokine essential for cell-mediated responses, than GP2-primed cells (Fig. 9). This suggests G7F activated T cells cross-react with GP2 presented in the context of HLA-A*0201. It should be noted that the data do not prove that G7F is immunogenic in Her-2/neu-expressing hosts. It remains to be determined if the human T-cell repertoire is capable of recognizing G7F and develop Her-2/neu-specific immunity.

Fig. 9.

INFγ production of splenic T cells in HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice primed with syngeneic DC pulsed with GP2 or G7F. Mice were immunized once with syngeneic DC loaded with GP2 or G7F. Splenocytes from immunized mice were harvested and restimulated in vitro thrice with DC loaded with varying concentrations of GP2. Error bars indicate standard error of mean. *p < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

With an enhanced capacity to stabilize surface HLA-A*0201 molecules, G7F should be investigated further as a candidate for inducing Her-2/neu-specific immunity. The computational analyses provided detailed mechanistic insights into the interactions of GP2 and the variants in the HLA-A*0201 binding groove. The simulations support the notion that amino acids in a given MHC bound peptide are inter-dependent: atoms in a given position may stabilize or de-stabilize interactions in distant regions of the peptide (Fremont et al., 1995; Leggatt et al., 1998; Meng and Butterfield, 2002; Sharma et al., 2001; Smith et al., 1996). The computational analysis revealed conformational features of the complexes that are consistent with experimental data.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant CA97990 (WSM). MAJ was supported by a grant from the Merck Research Scholar program from the American Foundation of Pharmaceutical Education (AFPE). We acknowledge National Science Foundation grant CHE-0354052 (JDE) for providing funding to MAJ and MLM. We thank Sai Chamarthy for help in the β2m conjugation.

Abbreviations

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MHC

major histocomptability complex

- DC

dendritic cells

Footnotes

Positions in peptide are abbreviated as P1, P2, P3, etc. Specific amino acids in peptide are indicated with one-letter code followed by position in the sequence (e.g. V6, F7). Amino acids of the MHC molecule are represented with three-letter code followed by position in the protein (e.g. Arg-97, Tyr-116).

References

- Abrams SI, Schlom J. Rational antigen modification as a strategy to upregulate or downregulate antigen recognition. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000;12:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Schreurs MW, Tafazzul G, de Boer AJ, Kawakami Y, Adema GJ, Figdor CG. Identification of a novel peptide derived from the melanocyte-specific gp100 antigen as the dominant epitope recognized by an HLA-A2.1-restricted anti-melanoma CTL line. Int. J. Cancer. 1995;62:97–102. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxevanis CN, Sotiriadou NN, Gritzapis AD, Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Cacoullos NT, Papamichail M. Immunogenic HER-2/neu peptides as tumor vaccines. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0692-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier M, Wiley DC. Importance of peptide amino and carboxyl termini to the stability of MHC class I molecules. Science (Washington, DC) 1994;265:398–402. doi: 10.1126/science.8023162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins EJ, Frelinger JA. Altered peptide ligand design: altering immune responses to class I MHC/peptide complexes. Immunol. Rev. 1998;163:151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disis ML, Grabstein KH, Sleath PR, Cheever MA. Generation of immunity to the HER-2/neu oncogenic protein in patients with breast and ovarian cancer using a peptide-based vaccine. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:1289–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremont DH, Stura EA, Matsumura M, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of an H-2K-b-ovalbumin peptide complex reveals the interplay of primary and secondary anchor positions in the major histocompatibility complex binding groove. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:2479–2483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan KT, Shimojo N, Walk SF, Engelhard VH, Maloy WL, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. Mutations in the alpha 2 helix of HLA-A2 affect presentation but do not inhibit binding of influenza virus matrix peptide. J. Exp. Med. 1988;168:725–736. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.2.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman RM. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns JJ, Batalia MA, Yan S, Collins EJ. Poor binding of a HER-2/neu epitope (GP2) to HLA-A2.1 is due to a lack of interactions with the center of the peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:36422–36427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggatt GR, Hosmalin A, Pendleton CD, Kumar A, Hoffman S, Berzofsky JA. The importance of pairwise interactions between peptide residues in the delineation of TCR specificity. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4728–4735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DR, Garboczi DN, Wiley DC. The antigenic identity of peptide–MHC complexes: a comparison of the conformations of five viral peptides presented by HLA-A2. Cell. 1993;75:693–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90490-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng WS, Butterfield LH. Rational design of peptide-based tumor vaccines. Pharm. Res. 2002;19:926–932. doi: 10.1023/a:1016497818471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng WS, Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Heller JB, Miranda GA, Glaspy JA, McBride WH, Economou JS. Alpha-fetoprotein-specific tumor immunity induced by plasmid prime-adenovirus boost genetic vaccination. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8782–8786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng WS, Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Heller JB, Dissette VB, Glaspy JA, McBride WH, Economou JS. Fine specificity analysis of an HLA-A2.1-restricted immunodominant T-cell epitope derived from human alpha-fetoprotein. Mol. Immunol. 2000a;37:943–950. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng WS, Von Grafenstein H, Haworth IS. A model of water structure inside the HLA-A2 peptide binding groove. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:1339–1346. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.9.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng WS, von Grafenstein H, Haworth IS. Water dynamics at the binding interface of four different HLA-A2–peptide complexes. Int. Immunol. 2000b;12:949–957. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J. Immunol. 1994;152:163–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KC, DiBrino M, Hull L, Coligan JE. The beta 2-microglobulin dissociation rate is an accurate measure of the stability of MHC class I heterotrimers and depends on which peptide is bound. J. Immunol. 1992;149:1896–1904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst MR, Salgaller ML, Southwood S, Robbins PF, Sette A, Rosenberg SA, Kawakami Y. Improved induction of melanoma-reactive CTL with peptides from the melanoma antigen gp100 modified at HLA-A*0201-binding residues. J. Immunol. 1996;157:2539–2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DA, Case DA, Caldwell JC, Seibel GL, Singh UC, Weiner P, Kollman PA. AMBER. 1991.

- Peiper M, Goedegebuure PS, Izbicki JR, Eberlein TJ. Pancreatic cancer associated ascites-derived CTL recognize a nine-amino-acid peptide GP2 derived from HER2/neu. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:2471–2475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiper M, Goedegebuure PS, Linehan DC, Ganguly E, Douville CC, Eberlein TJ. The HER2/neu-derived peptide p654–662 is a tumor-associated antigen in human pancreatic cancer recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:1115–1123. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples GE, Goedegebuure PS, Smith R, Linehan DC, Yoshino I, Eberlein TJ. Breast and ovarian cancer-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize the same HER2/neu-derived peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:432–436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas A, Butterfield LH, McBride WH, Jilani SM, Bui LA, Vollmer CM, Lau R, Dissette VB, Hu B, Chen AY, Glaspy JA, Economou JS. Genetic immunization for the melanoma antigen MART-1/Melan-A using recombinant adenovirus-transduced murine dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2865–2869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rognan D, Scapozza L, Folkers G, Daser A. Molecular dynamics simulation of MHC–peptide complexes as a tool for predicting potential T-cell epitopes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:11476–11485. doi: 10.1021/bi00204a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongcun Y, Salazar-Onfray F, Charo J, Malmberg KJ, Evrin K, Maes H, Kono K, Hising C, Petersson M, Larsson O, Lan L, Appella E, Sette A, Celis E, Kiessling R. Identification of new HER2/neu-derived peptide epitopes that can elicit specific CTL against autologous and allogeneic carcinomas and melanomas. J. Immunol. 1999;163:1037–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Schwarz SL, Spiess PJ, Wunderlich JR, Parkhurst MR, Kawakami Y, Seipp CA, Einhorn JH, White DE. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat. Med. 1998;4:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert J, Sidney J, Celis E, Kubo RT, Grey HM, Sette A. Prominent role of secondary anchor residues in peptide binding to HLA-A2.1 molecules. Cell. 1993;74:929–937. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter RD, Cresswell P. Impaired assembly and transport of HLA-A and -B antigens in a mutant T × B cell hybrid. EMBO J. 1986;5:943–949. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, Fowler P, Nayersina R, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Oseroff C, Yuan L, Ruppert J, et al. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T-cell epitopes. J. Immunol. 1994a;153:5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, Fowler P, Nayersina R, Kast WM, Melief CJM, Oseroff C, Yuan L, Ruppert J, Sidney J, Del Guercio M-F, Southwood S, Kubo RT, Chestnut RW, Grey HM, Chisari FV. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T-cell epitopes. J. Immunol. 1994b;153:5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma AK, Kuhns JJ, Yan S, Friedline RH, Long B, Tisch R, Collins EJ. Class I major histocompatibility complex anchor substitutions alter the conformation of T-cell receptor contacts. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:21443–21449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, Levin WJ, Stuart SG, Udove J, Ullrich A, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Reid SW, Harlos K, McMichael AJ, Stuart DI, Bell JI, Jones EY. Bound water structure and polymorphic amino acids act together to allow the binding of different peptides to MHC class I HLA-B53. Immunity. 1996;4:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkus WJ, Zeh H.J.d., Salter RD, Lotze MT. Identification of T-cell epitopes: rapid isolation of class I-presented peptides from viable cells by mild acid elution. J. Immunother. 1993;14:94–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber G, Leder GH, Storkus WT, Lotze MT, Modrow S, Szekely L, Wolf H, Klein E, Karre K, Klein G. Identification of wild-type and mutant p53 peptides binding to HLA-A2 assessed by a peptide loading-deficient cell line assay and a novel major histocompatibility complex class I peptide binding assay. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:765–768. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng JM, Hogan KT. Both major and minor peptide-binding pockets in HLA-A2 influence the presentation of influenza virus matrix peptide to cytotoixc T lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol. 1994;31:459–470. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend A, Ohlen C, Bastin J, Ljunggren HG, Foster L, Karre K. Association of class I major histocompatibility heavy and light chains induced by viral peptides [see comments]. Nature. 1989;340:443–448. doi: 10.1038/340443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burg SH, Visseren MJ, Brandt RM, Kast WM, Melief CJ. Immunogenicity of peptides bound to MHC class I molecules depends on the MHC–peptide complex stability. J. Immunol. 1996;156:3308–3314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello A, Marchesini D, Furze J, Sherman LA, Chesnut RW. Analysis of the HLA-restricted influenza-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in transgenic mice carrying a chimeric human-mouse class I major histocompatibility complex. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1007–1015. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth PA, Vitiello A, Sidney J, Keogh E, Chestnut RW, Grey H, Sette A. Differences and similarities in the A2.1-restricted cytotoxic T-cell repertoire in humans and human leukocyte antigen-transgenic mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:97–101. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino I, Goedegebuure PS, Peoples GE, Parikh AS, DiMaio JM, Lyerly HK, Gazdar AF, Eberlein TJ. HER2/neu-derived peptides are shared antigens among human non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3387–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweerink HJ, Gammon MC, Utz U, Sauma SY, Harrer T, Hawkins JC, Johnson RP, Sirotina A, Hermes JD, Walker BD, et al. Presentation of endogenous peptides to MHC class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes in transport deletion mutant T2 cells. J. Immunol. 1993;150:1763–1771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]