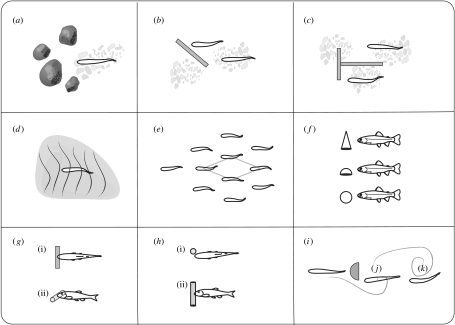

Figure 2.

Schematic summary of key field, laboratory and theoretical studies which have investigated the effects of biotically and abiotically generated wakes on fish swimming kinematics and behaviour. Stream observations of salmonids taking advantage of reduced flows behind aggregations of (a) boulders (Shuler et al. 1994), (b) log baffles (McMahon & Gordon 1989) and (c) Plexiglas T-structures (Fausch 1993). (d) Laboratory manipulations of substratum ripple height and spacing on cod (Gerstner 1998). (e) A schooling fish swimming in the vortex wake of preceding members can gain a hydrodynamic advantage if a diamond formation is adopted (Breder 1965; Weihs 1973). (f) Lateral view showing that brook trout choose to swim behind cones, half-spheres and spheres less when their ability to detect flow is blocked (Sutterlin & Waddy 1975). (g(i)) Dorsal and (g(ii)) lateral view of fish entraining on relatively small diameter (less than 30% of standard body length) horizontal cylinders (Webb 1998). (h(i)) Dorsal and (h(ii)) lateral view of brook trout, river chub and smallmouth bass entraining on relatively small diameter vertical cylinders (Sutterlin & Waddy 1975; Webb 1998; Montgomery et al. 2003). Rainbow trout (i) riding in the bow wake, (j) entraining and (k) exploiting vortices behind a relatively large (50% standard body length) D-section cylinder (Liao et al. 2003a,b; Liao 2006). See text for details.