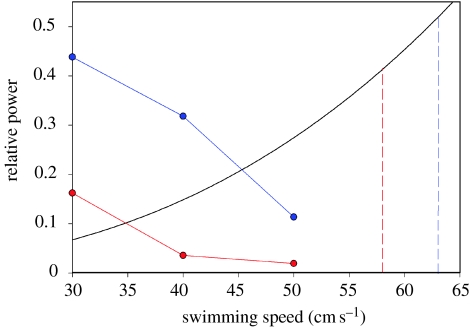

Figure 28.

The relative total power output of the red musculature as a function of swimming speed at 10°C. The blue curve represents power output of the red musculature from cold-acclimated fish and the red curve represents power output from warm-acclimated fish. Relative power output of the red musculature was determined by integrating the power output of the red muscle along the length of the fish, and then normalizing to the integrated power output of the red+pink muscle of fish swimming at 80 cm s−1 and 20°C (as outlined in Rome et al. 2000). We chose power output at 80 cm s−1 and 20°C as an estimate of the maximum power output that the combined red and pink musculature can generate during swimming. This seems reasonable because 80 cm s−1 is close to the swimming speed of initial white-muscle recruitment at 20°C, and we know that both pink and red muscle are recruited at this swimming speed (Coughlin & Rome 1999). The relative power required for swimming at slower speeds (black curve) was calculated based on the assumption that power required is proportional to the cube of swimming speed (Webb 1978): relative power required is proportional to (speed/80)3. This figure shows that there is a very large increase in total red-muscle power output associated with thermal acclimation, which probably permits the cold-acclimated fish to swim at 40 cm s−1 with the red muscle alone, whereas the warm-acclimated fish cannot. However, at swimming speeds of 58–63 cm s−1, the red musculature generates very little power and only a small proportion of the total power required to swim at that speed. Adapted from Swank & Rome (2001). Red dashed line, warm-acclimated white muscle recruitment speed (58 cm s−1); blue-dashed line, cold-acclimated recruitment speed (63 cm s−1).