Abstract

The cgtA gene, coding for the conserved G protein CgtA, is essential in bacteria. In contrast to a previous report, here we show by using genetic analysis that cgtA is essential in Vibrio cholerae even in a ΔrelA background. Depletion of CgtA affected the growth of V. cholerae and rendered the cells highly sensitive to the replication inhibitor hydroxyurea. Overexpression of V. cholerae CgtA caused distinct elongation of Escherichia coli cells. Deletion analysis indicated that the C-terminal end of CgtA plays a critical role in its proper function.

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the severe diarrheal disease cholera, is a fast-growing organism. Among various regulatory proteins involved in bacterial growth management, the essential GTP-binding proteins have been shown to play critical roles, although the exact mechanisms are yet to be elucidated. The GTP-binding protein CgtA, coded by the cgtA gene, belonging to Obg subfamily has been found to be highly conserved and essential in prokaryotes (14, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 27). Studies conducted with different prokaryotic organisms have suggested functional roles of the CgtA/Obg protein in various physiological processes, like regulation of initiation of sporulation (30), DNA replication (15, 26), chromosome partitioning (14), replication fork stability (7), chromosome segregation (8), ribosome maturation (12, 25), and maintaining the steady-state level of ppGpp during exponential growth (13). It has been demonstrated that Escherichia coli temperature-sensitive obgE (cgtA) mutant cells form long filaments with expanded, nonpartitioned chromosomes (14). Foti et al. (7) isolated an obgE mutant that was sensitive to various replication inhibitors, like hydroxyurea (HU). Further studies by the same group showed that ObgE is required for cell cycle progression in E. coli (8). Sato et al. (25) recently showed that ObgE is associated with several ribosomal proteins. Thus, in E. coli CgtA/ObgE appears to be involved in ribosome biogenesis. In Vibrio harveyi, an important species of the genus Vibrio, CgtA is an essential protein associated with the 50S ribosomal subunit (27).

Recently, the crystal structure of the full-length Obg protein from Thermus thermophilus, a thermophilic organism, was determined by Kukimoto-Niino et al. (16), whose analysis revealed three domains, a central GTP-binding domain flanked by N- and C-terminal domains designated OBG and OCT, respectively, that are unique to the Obg protein. The crystal structure of the Obg protein of T. thermophilus also indicated that the G domain might interact with the OCT domain of the adjacent Obg molecule, and such interactions may facilitate nucleotide exchange under some biological conditions (16). The crystal structure of C-terminally truncated Obg of Bacillus subtilis, a gram-positive organism, showed that ppGpp, the effector molecule of a bacterial stringent response, was present in the G domain, and Buglino et al. proposed that Obg probably recognizes this nucleotide in response to starvation or stress (3). Recent studies also indicated that CgtA interacts with the SpoT protein, which hydrolyzes ppGpp (24, 32). It had been shown previously that for coupling DNA replication to the growth rate of bacteria, ppGpp synthesis might play an important role (4). All this information strongly suggests that CgtA somehow influences the DNA replication process in bacterial cells. Altogether, it appears that the CgtA works like a molecular switch controlling ribosome biogenesis under normal growth conditions and also modulates various vital functions of cells, including DNA replication under stress conditions.

In the present study we demonstrated that the cgtA gene is essential in V. cholerae, and in contrast to a recent report (24), it was found that cgtA is still an essential gene in V. cholerae with a ΔrelA genetic background. Furthermore, unlike depletion of CgtA in E. coli, depletion of CgtA in V. cholerae does not lead to cell elongation, but as in E. coli, the cgtA gene product is involved in chromosome segregation and/or replication in V. cholerae, as revealed by using the replication inhibitor HU. It was observed that overexpression of CgtA also affects the growth and cell morphology of both E. coli and V. cholerae. Deletion analysis indicated that the C-terminal-domain-coding sequence of the cgtA gene of V. cholerae is needed for proper functioning of its product.

(Part of this work was presented at the Symposium on Frontiers in Biological Research, Visva Bharati, Shantiniketan, India, 3 to 5 August 2007.)

Bacterial strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Oligonucleotides used for PCR and sequencing are shown in Table 2. Both E. coli and V. cholerae cells were routinely grown in Luria broth (LB) at 37°C with shaking as described previously (19). For plate culture LB was supplemented with 1.5% agar (LA). E. coli strain DH5α and plasmid pDrive (Table 1) were used for cloning. For the cgtA depletion assay, cells were grown overnight at 37°C in LB containing appropriate antibiotics and 0.01% arabinose (27). The culture was subsequently diluted 1:1,000 in LB or LB containing 0.01% arabinose (Sigma-Aldrich, United States) and incubated at 37°C with aeration for 5 h. Samples were serially diluted and spotted on LA plates containing either 0.01% arabinose or 0.4% glucose or on LA plates. For the HU (Sigma-Aldrich) assay the LA plates or LB contained either 1.0 mM HU or 1.0 mM HU plus 0.01% arabinose. It was determined in this study that HU concentrations up to 1.0 mM had no effect on the growth or cell morphology of V. cholerae wild-type cells. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations unless otherwise indicated: ampicillin (Amp), 100 μg/ml; streptomycin (Sm), 100 μg/ml; kanamycin (Kan), 50 μg/ml for E. coli and 40 μg/ml for V. cholerae; chloramphenicol (Cam), 34 μg/ml for E. coli and 3 μg/ml for V. cholerae; and tetracycline (Tet), 10 μg/ml for E. coli and 1 μg/ml for V. cholerae.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| N16961 | Wild type, O1 serogroup, biotype El Tor; Smr | 11 |

| SS1 | N16961::pKAS32 ΔcgtA::cam; Ampr Camr Sms | This study |

| NcgtA13 | N16961 ΔcgtA::cam [pSBK]; Ampr Camr Kanr Smr | This study |

| N16961-R13 | N16961 ΔrelA::kan; Kanr Smr | 5 |

| N16961-R13(pBAD24) | N16961-R13 carrying plasmid pBAD24; Ampr Kanr Smr | This study |

| NRcgtA1 | N16961-R13 ΔcgtA::tet carrying plasmid pSBC; Camr Kanr Smr Tetr | This study |

| N16961(pBAD24) | N16961 carrying plasmid pBAD24; Ampr Smr | This study |

| N16961(pSBORF) | N16961 carrying plasmid pSBORF; Ampr Smr | This study |

| N16961(pSBΔ87) | N16961 carrying plasmid pSBΔ87; Ampr Smr | This study |

| N16961(pSBΔ189) | N16961 carrying plasmid pSBΔ189; Ampr Smr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F′ endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(argF-lacZYA)U169 (φ80dlacZΔM15) | Promega |

| SM10λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu λpir R6K; Kanr | 10 |

| CF1648 | Wild-type MG1655 | 33 |

| CF1693 | MG1655 spoT207 relA251; Camr Kanr | 33 |

| CF1648(pBAD24) | CF1648 carrying plasmid pBAD24; Ampr | This study |

| CF1648(pSBORF) | CF1648 carrying plasmid pSBORF; Ampr | This study |

| CF1648(pSBΔ87) | CF1648 carrying plasmid pSBΔ87; Ampr | This study |

| CF1648(pSBΔ189) | CF1648 carrying plasmid pSBΔ189; Ampr | This study |

| CF1693(pBAD24) | CF1693 carrying plasmid pBAD24; Ampr Camr Kanr | This study |

| CF1693(pSBORF) | CF1693 carrying plasmid pSBORF; Ampr Camr Kanr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBR322 | pMB1 origin, general purpose cloning vector; Ampr Tetr | New England Biolabs |

| pCR4TOPO | pUC origin, high-copy-number cloning vector; Ampr Kanr | Invitrogen, United States |

| pDrive | pUC origin, high-copy-number cloning vector; Ampr Kanr | Qiagen, Germany |

| pKAS32 | rpsL suicide vector with oriR6K mobRP4; Ampr | 28 |

| pROTet.E | ColE1 origin, high-copy-number expression vector; Camr | BD Biosciences |

| pUC4K | Source of the kan cassette; Ampr Kanr | Pharmacia |

| pSS1 | 1.45-kb PCR-amplified cgtA gene region of V. cholerae strain N16961 in pCR4TOPO; Ampr Kanr | This study |

| pSS2 | 0.48-kb internal cgtA fragment from pSS1 replaced with 0.78 kb of cam cassette from pROTet.E; Ampr Camr Kanr | This study |

| pSS9 | 1.76-kb EcoRI fragment containing ΔcgtA::cam allele from pSS2 cloned in similarly digested pKAS32; Ampr Camr | This study |

| pSS3 | 0.31-kb internal cgtA fragment from pSS1 replaced with PCR-amplified 1.62 kb of tet cassette of pBR322 using primers Ptc-F and Ptc-R; Ampr Kanr Tetr | This study |

| pSS2.31 | 2.31-kb ΔcgtA::tet fragment from pSS3 PCR amplified using primers CgtArt-F and CgtArt-R and cloned in pDrive; Ampr Kanr Tetr | This study |

| pSS2.42 | 2.42-kb KpnI-SacI fragment containing ΔcgtA::tet allele from pSS2.31 cloned in similarly digested pKAS32; Ampr Tetr | This study |

| pBAD24 | ori pBR322, l-arabinose-inducible vector; Ampr | 9 |

| pSBORF | 1.2-kb cgtA ORF cloned in pBAD24; Ampr | This study |

| pSBK | 1.24-kb kan cassette of pUC4K cloned into the PstI site of pSBORF; Ampr Kanr | This study |

| pSBC | pSBORF digested with PstI and BglI; 1.2-kb fragment was removed, end filled, and ligated to 0.78-kb cam cassette of pROTet.E; Camr | This study |

| pSBΔ87 | pSBORF with 87-bp deletion from 3′ end of the cgtA ORF; Ampr | This study |

| pSBΔ189 | pSBORF with 189-bp deletion from 3′ end of the cgtA ORF; Ampr | This study |

TABLE 2.

Sequences of primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Cgta-F | CCGGAAATTCGTTAGCATCGAAACTGCTG | PCR |

| Cgta-R | CGCGGATCCAACTAAGTTGCGGCATACCA | PCR |

| Cgtaexp-F | GGAATTCCATATGAGTGGAGGAAAAATGAAAT (EcoRI) | PCR |

| CgtArt-F | AAAGTTCAAGCTGGTGATGG | PCR, sequencing |

| CgtArt-R | TTCCGCTTCTCTTGGTAAGG | PCR |

| CtAe-R | AACTGCAGCGGCATACCAGTAAG (PstI) | PCR |

| CtAd-R | AACTGCAGTCAAGCCAATCCGTCTTTATG (PstI) | PCR |

| Ctl-F | GGGCGGTAAAGTAGTTGCTG | PCR |

| Ctl-R | ATAACATCTGCCCTGCCTGA | PCR |

| PBAD-F | TCGCTAACCAAACCGGTAAC | Sequencing |

| PBAD-R | GATGCCTGGCAGTTCCCTAC | Sequencing |

| Ptc-F | TGCCTCGAGACGTCTAAGAA | PCR |

| Ptc-R | CGGTGATTCATTCTGCTAACC | PCR |

Bold type indicates sites for the restriction enzymes indicated in parentheses. Underlining indicates a stop codon.

The cgtA gene is essential in V. cholerae.

During this study, Raskin et al. (24) reported that in V. cholerae cgtA is an essential gene, as it is in other bacteria. Our experimental data support the observation made by Raskin et al. (24). To show this, initially chromosomal DNA flanking the cgtA gene (The Institute for Genome Research annotation no. VC0437) was PCR amplified using the Cgta-F/Cgta-R primer pair (Table 2), which was followed by cloning of the amplicon in pCR4TOPO (Table 1). The recombinant suicide plasmid pSS9 (Ampr Camr), a derivative of pKAS32 (Ampr) (Table 1), containing the ΔcgtA::cam allele was constructed using plasmids pSS1 and pSS2, as shown in Table 1. Plasmid pSS9 was maintained in E. coli strain SM10λpir (Table 1). Conjugal transfer of pSS9 into V. cholerae wild-type strain N16961 (Smr) (Table 1) generated only merodiploid transconjugant SS1 (Ampr Camr Sms) (Table 1) containing both wild-type and disrupted cgtA alleles. Since the suicide vector pKAS32 contains the wild-type rpsL gene of E. coli that codes for the ribosomal protein S12 and since mutations in this gene that confer Smr are recessive in a strain expressing the wild-type protein (28), when the wild-type S12 protein is expressed on an integrated plasmid like pKAS32, it assembles into ribosomes and confers an Sms phenotype upon an Smr strain. Based on this rationale, the SS1 transconjugant (Ampr Camr Sms) was selected and used for a double-crossover experiment (28) to obtain the desired deletion in the cgtA gene of V. cholerae using a method essentially described previously (5). Despite several attempts we were unable to obtain a ΔcgtA V. cholerae strain. This result was further supported by the fact that deletion of the chromosomal cgtA gene of SS1 by a double-crossover event was possible only when the CgtA function was provided in trans by helper plasmid pSBK (Ampr Kanr) (Table 1), generating strain NcgtA13 (Ampr Camr Kanr Smr) (Table 1). Plasmid pSBK was a derivative of pSBORF (Ampr) (Table 1) containing a kanamycin resistance gene (kan) cassette of pUC4K (Table 1) and the entire cgtA open reading frame (ORF) cloned under the arabinose-inducible promoter PBAD in the pBAD24 vector (Ampr), as shown in Table 1. The 1.2-kb cgtA ORF was obtained by PCR amplification using the Cgtaexp-F/CtAe-R primer pair (Table 2). The presence of the ΔcgtA::cam allele in NcgtA13 was confirmed by PCR analysis using primers Cgta-F and Ctl-R (Table 2) and by DNA sequencing (data not shown). Strain NcgtA13, however, was viable without induction of arabinose due to leaky expression from the PBAD promoter, which is a common observation made by other laboratories working with this promoter (9, 24). When the growth of NcgtA13 in the presence of arabinose (0.01%) was compared with the growth of this strain in the absence of arabinose by using a spot dilution assay, it was found that the growth of uninduced cells was definitely slower than that of induced cells (Fig. 1). To further establish that cgtA is indeed essential in V. cholerae, we performed the spot dilution assay on plates containing glucose, which is known to be an inhibitor of the PBAD promoter (9). The results showed that the growth of strain NcgtA13 on these plates was highly compromised (Fig. 1). However, microscopic examination of CgtA-depleted V. cholerae cells showed normal cellular morphology like that of wild-type strain N16961 (Fig. 2A; data not shown). It should be noted that Sikora et al. (27) reported similar findings when cells of V. harveyi were depleted of CgtA.

FIG. 1.

Effect of CgtA depletion on growth of V. cholerae. Experimental and control strains were grown in LB in the absence (− ara) or presence (+ ara) of arabinose (0.01%), as indicated on the left. After 5 h of growth, 10-fold serial dilutions (from left to right) were spotted onto LA plates without or with arabinose (0.01%) or with glucose (0.4%), as indicated on the right.

FIG. 2.

Effect of HU on CgtA-depleted V. cholerae cells. (A) Phase-contrast micrographs of cells grown in LB without (− ara) or with (+ ara) arabinose (0.01%) and HU (1 mM) as indicated. (B) Cells were grown in LB with or without arabinose for 5 h, and 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted on plates containing only HU (1 mM) or HU (1 mM) plus arabinose (0.01%) as indicated.

V. cholerae ΔrelA ΔcgtA mutant is not viable.

Raskin et al. (24) reported that V. cholerae ΔcgtA cells are viable if the parent strain is a relA null mutant, which apparently indicates critical involvement of the cgtA gene function with the stringent response of the organism. Furthermore, we know that spoT is essential in a relA+ background in both E. coli and V. cholerae (5, 24, 33). It has been shown that CgtA of E. coli copurifies with SpoT, indicating that these two proteins interact with each other (32). By using a two-hybrid assay, Raskin et al. (24) showed that CgtA of V. cholerae also interacts with SpoT, and these authors suggested that the essential function of CgtA is to repress the stringent response by critically regulating SpoT hydrolase activity to maintain low ppGpp levels when vibrios are growing in a nutrient-rich environment. To understand the function of CgtA in a relA mutant background, we wanted to develop a V. cholerae ΔrelA ΔcgtA strain of N16961, as recently demonstrated by Raskin et al. (24). To do this, we constructed another recombinant suicide vector, pSS2.42 (Ampr Tetr) (Table 1) containing the ΔcgtA::tet allele, using plasmids pSS1, pSS3, and pSS2.31 (Table 1), and then integrated pSS2.42 into the chromosome of V. cholerae ΔrelA strain N16961-R13 (Kanr Smr) (Table 1) in a first crossover event. We used the tetracycline resistance gene (tet) cassette obtained by PCR amplification of pBR322 DNA (Ampr Tetr) (Table 1) with primers Ptc-F and Ptc-R (Table 2) as a marker for ease of selection. Integration of pSS2.42 in the cgtA locus of N16961-R13 was confirmed by PCR analyses using the CgtArt-F/CgtArt-R and Ctl-F/Ctl-R primer pairs (Table 2; data not shown). Then, to delete the cgtA gene from N16961-R13, we performed a double-crossover experiment. However, several attempts to obtain a V. cholerae ΔrelA ΔcgtA double mutant were unsuccessful, indicating that although N16961-R13 is a relA null strain (5), it appears that cgtA is essential in the RelA-negative V. cholerae cells. If this is true, then we should be able to delete the chromosomal cgtA gene of a V. cholerae ΔrelA strain if the CgtA function can be provided in trans, similar to what has been done to prove the essentiality of cgtA in wild-type V. cholerae cells. As expected, we easily obtained several V. cholerae ΔrelA ΔcgtA clones when the CgtA function was provided in trans in this strain by helper plasmid pSBC (Camr) (Table 1) containing the cgtA ORF under the arabinose-inducible promoter PBAD, as in pSBK (Table 1) used for constructing the chromosomal deletion of cgtA in wild-type V. cholerae strain N16961. The chloramphenicol resistance gene (cam) cassette present in plasmid pSBC was obtained by EcoRV digestion of plasmid pROTet.E (Camr) (Table 1). The V. cholerae ΔrelA ΔcgtA strain bearing plasmid pSBC was designated NRcgtA1 (Camr Kanr Smr Tetr) (Table 1). To demonstrate the essentiality of cgtA in the V. cholerae ΔrelA strain, we performed similar spot dilution assays, and the results corroborated the results obtained with V. cholerae strain NcgtA13 (data not shown). It should be mentioned that very recently two different groups working on the stringent response and cgtA gene function of E. coli failed to isolate an E. coli ΔcgtA ΔrelA double mutant (8, 13). Altogether, it appears that the cgtA gene is essential in a relA mutant background in both V. cholerae and E. coli.

Depletion of CgtA results in sensitivity to a replication inhibitor.

In E. coli, depletion of the CgtA homolog ObgE leads to elongated cells with a defect in chromosome partitioning (14). Foti et al. (7) showed that the replication inhibitor HU has a lethal effect on a viable insertion allele of ObgE in E. coli cells. HU is an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase and depletes cells of deoxynucleotide pools, leading to a defect in DNA replication (7, 29). When V. cholerae NcgtA13 cells were grown in LB without arabinose, the growth was slow compared to that of cells grown with 0.01% arabinose, but there was no change in cell morphology as determined by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 2A). Wild-type strain N16961 carrying the pBAD24 vector was used as a control (data not shown). The results are consistent with the findings of Raskin et al. (24). We hypothesized that due to depletion of CgtA in NcgtA13 some impairment in the DNA replication function may have occurred, which may have been responsible for the slow growth of the cells, and thus, the use of any replication inhibitor may further inhibit the growth of CgtA-depleted V. cholerae cells. To test this possibility, NcgtA13 cells were grown in LB with or without arabinose, and serial dilutions were spotted on LA plates containing only HU (final concentration, 1.0 mM) or HU plus arabinose (0.01%) (Fig. 2B). Wild-type strain N16961 carrying the pBAD24 vector was used as a control (data not shown). Interestingly, strain NcgtA13 showed a slight growth defect in LA plates containing HU when the cells were grown with 0.01% arabinose, which could be overcome by spotting the cells on LA plates containing both HU and 0.01% arabinose (Fig. 2B). In sharp contrast, a significant growth defect of the NcgtA13 strain was observed when the cells were grown in the absence of arabinose and dilutions were similarly spotted on LA plates containing only HU (Fig. 2B). As expected, the growth defect was less severe when the same cells were spotted on LA plates containing both HU and arabinose, indicating that HU may impair DNA replication function further in CgtA-depleted V. cholerae cells. We performed similar experiments using the ΔcgtA ΔrelA strain NRcgtA1 provided with CgtA in trans by helper plasmid pSBC, and the results were similar to those obtained with CgtA-depleted cells of NcgtA13 (data not shown). Moreover, when HU was added to LB inoculated with NcgtA13 (Fig. 2A) or NRcgtA1 (data not shown) without arabinose, the depleted cells had an elongated cellular morphology. As controls, we used N16961(pBAD24) and N16961-R13(pBAD24) (Table 1), both of which showed no defect in growth or in cellular morphology in the presence of HU under any growth conditions tested for the depleted strains (data not shown). The results indicate that a basal cellular level of CgtA is most likely needed to overcome the HU-induced replication inhibition stress in V. cholerae, and thus, CgtA may play a critical role directly or indirectly in replication and growth of V. cholerae. In the case of wild-type V. cholerae N16961 cells, a tolerable concentration of HU had no such effect, indicating that the cells were able to overcome the HU-mediated replication-related stress. However, it appears that when the cells were depleted of CgtA, the replication process was affected, leading to a growth defect, although the mechanism(s) is currently not known.

Since it was reported that CgtA regulates the cellular ppGpp level during exponential growth of cells (13, 24), we determined the intracellular ppGpp concentrations for CgtA-depleted strain NcgtA13, and nucleotides were separated by thin-layer chromatography essentially as described by Das and Bhadra (5). The results showed that the ppGpp level increased as cells were depleted of CgtA (data not shown), which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (13, 24) and indicates that CgtA is needed to maintain the normal cellular concentration of ppGpp in the cell.

cgtA overexpression phenotypes of V. cholerae.

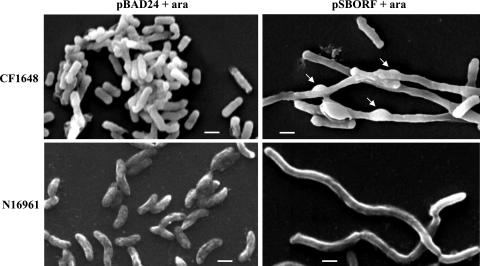

Previous studies of E. coli indicated that overexpression of cgtA/obgE is deleterious for its growth, probably due to aberrant chromosome segregation, which suggested that the protein encoded by the gene is involved directly or indirectly in chromosome partitioning (6, 14). We wanted to know whether overexpression of the cgtA gene of V. cholerae in a heterologous genetic background (e.g., E. coli) resulted in similar behavior. To investigate this, recombinant plasmid pSBORF was transformed into wild-type E. coli strain CF1648 (an MG1655 strain) (Table 1), generating strain CF1648(pSBORF) (Ampr) (Table 1). When an overnight culture of CF1648(pSBORF) cells was diluted 1:1,000 in fresh LB containing 0.2% arabinose, we found that the growth of the overexpressing cells was slightly slower than that of control strain CF1648 carrying the empty vector pBAD24 [CF1648(pBAD24) (Table 1)] (data not shown). The effect was very similar to the overexpression phenotype of E. coli obgE, a cgtA homolog (14). Thus, it appears that the CgtA protein of V. cholerae has a similar function in the E. coli background. Furthermore, it has been reported that overexpression of ObgE in E. coli causes aberrant chromosomal partitioning, leading to long elongated cells (14). To examine the cellular morphology of CF1648(pSBORF), we performed phase-contrast microscopy by using a Nikon eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Japan) and the method of Bomchil et al. (2). We also introduced the recombinant plasmid pSBORF into the N16961 strain of V. cholerae, generating strain N16961(pSBORF) (Ampr Smr) (Table 1), and tested the effects of cgtA overexpression in the homologous genetic background. As a control we used N16961 bearing the empty vector pBAD24 [N16961(pBAD24) (Table 1)]. Interestingly, although we induced cgtA gene expression in N16961(pSBORF) cells by adding 0.2% arabinose to an overnight culture diluted 1:1,000 in fresh LB, as was done in the case of E. coli CF1648(pSBORF), the growth of V. cholerae cells was not inhibited to the same extent as the growth of E. coli strain CF1648(pSBORF) cells (data not shown). The results suggest that unlike E. coli cells, V. cholerae cells with overexpressed CgtA can partially overcome the deleterious effect on growth. Alternatively, it is also possible that the CgtA protein was not expressed at the same level in these organisms, which should be investigated further. For a detailed investigation of the effects of excess CgtA on the cell morphology of E. coli and V. cholerae we performed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) essentially as described previously (2) using both normal cells and cells overexpressing CgtA. The SEM analysis of both E. coli and V. cholerae cells revealed elongated cell morphology (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we noticed that overexpression of CgtA in E. coli, but not overexpression of CgtA in V. cholerae, caused bulging in certain areas of the cell surfaces of elongated cells (Fig. 3). At present, the reason for this phenomenon is unknown, but it may have been due to formation of inclusion bodies consisting of overexpressed CgtA protein.

FIG. 3.

SEM analysis of morphology of bacterial cells overexpressing CgtA. The top and bottom panels show SEM of E. coli and V. cholerae cells, respectively. V. cholerae (N16961 wild-type) or E. coli (CF1648 wild-type) cells carrying the cgtA expression plasmid pSBORF or an empty vector (pBAD24) were used as controls. Cells were grown in LB with arabinose (0.2%) for 5 h, and samples were processed for SEM and visualized using a VEGA II LSU microscope (Tescan, Czech Republic) at 10 kV. The arrows indicate distinct bulging of the surface of E. coli cells, which is not present in V. cholerae. Bar, 1 μm.

Recent studies of CgtA indicated that it could regulate the cellular levels of ppGpp in V. cholerae by interacting with the ppGpp hydrolase protein SpoT (24). Wout et al. (32) have also shown that E. coli CgtA interacts with SpoT. It is well known that ppGpp at a high cellular concentration inhibits DNA replication in a reversible manner (31). Again, it was previously reported that ppGpp can down regulate the expression of the DnaA protein (4), the major protein needed for DNA replication initiation, and it was shown that a reduction in the DnaA level leads to a replication defect in E. coli (26). Structural and biochemical analyses of Obg/CgtA from B. subtilis revealed that ppGpp could bind the active site of this protein, and thus Obg/CgtA has evolved to recognize this molecule in response to changes in the cellular environment (3). Jiang et al. (13) have recently shown that the ppGpp level is regulated by CgtA only during exponential growth of the cells and not during the stringent response. Based on the existing information described above, we initially hypothesized that any change in the optimal cellular level of CgtA might directly affect the basal cellular level of the global regulator ppGpp, which in turn modulates various vital cellular functions leading to the observed phenotypes. To confirm our hypothesis, we overexpressed CgtA of V. cholerae in the well-studied ppGpp0 E. coli ΔrelA ΔspoT strain CF1693 derived from CF1648 (Table 1) and analyzed the cellular morphology by using phase-contrast microscopy. While overexpression of CgtA in CF1693 due to plasmid pSBORF [CF1693(pSBORF) (Table 1)] caused elongation of about 50% of the cells, in the parent ppGpp+ strain CF1648 similar overexpression affected about 65% of the cells. CF1693 and CF1648 cells, both carrying the empty vector pBAD24, were used as controls (Table 1), and they had morphologies similar to those of their respective host cells without any vector DNA (data not shown). The experiments were repeated at least three times, and average values are given here. It should be mentioned that CF1693 itself had a slightly elongated cell morphology during the log phase of growth, but the number of elongated cells was very low (18). Since both ppGpp+ and ppGpp0 cells of E. coli showed elongation phenotypes due to CgtA overexpression, it appears that the effect may not have been due to alteration of cellular ppGpp levels, which warrants further investigation.

C-terminal deletion analysis of the CgtA-coding gene.

Since very little information is currently available about the roles of various domains of CgtA/Obg proteins, we designed and cloned two truncated cgtA ORFs of V. cholerae with 87- and 189-bp deletions from the C-terminal coding region under the arabinose-inducible promoter PBAD of the vector pBAD24, generating recombinant plasmids pSBΔ87 and pSBΔ189 (Table 1), respectively. For construction of recombinant plasmid pSBΔ87 (Ampr) (Table 1), the cgtA ORF (11) of V. cholerae was PCR amplified using primers Cgtaexp-F and CtAd-R (Table 2) and cloned in vector pBAD24 DNA to obtain recombinant plasmid pSBΔ87. To avoid any translational fusion between the truncated 3′ end of the cgtA insert and vector DNA in pSBΔ87, a termination codon was included in the DNA sequence of reverse primer CtAd-R (Table 2), so that pSBΔ87 should have precisely coded for a truncated CgtA protein with 29 amino acids deleted from its C-terminal end. This was confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown). To construct recombinant plasmid pSBΔ189, plasmid pSBORF DNA (Table 1) was partially digested with the HindIII enzyme to remove 189 bp of the cgtA ORF (11) from the 3′ end along with 12 bp of the vector DNA (9), which was followed by religation of the DNA fragment and generation of the pSBΔ189 clone. Plasmid pSBΔ189 should have coded for a C-terminally truncated CgtA protein with a peptide that was five amino acids longer due to a translational fusion with the vector sequence, which was confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown). To check that the pSBΔ87 and pSBΔ189 deletion constructs were able to produce the expected C-terminally truncated CgtA proteins with molecular masses of ∼41 and ∼38 kDa, respectively, each of the constructs described above was transformed in E. coli CF1648 (1) or electroporated in V. cholerae N16961 (21) cells, generating the corresponding strains CF1648(pSBΔ87), CF1648(pSBΔ189), N16961(pSBΔ87), and N16961(pSBΔ189) (Table 1). When whole-cell lysates of these strains were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a method described previously (10), truncated CgtA proteins with the expected molecular masses were indeed overexpressed in V. cholerae (Fig. 4A), as well as in E. coli (data not shown). When a 29-amino-acid C-terminally truncated CgtA protein, designated CgtAΔ29, was overexpressed in CF1648, it retained the cell elongation effect (Fig. 4B), but the frequency of elongated cells was found to be about 30%, which is an almost twofold reduction compared to the effect of full-length CgtA protein. On the other hand, overexpression of a 62-amino-acid C-terminally truncated CgtA protein, designated CgtAΔ62, in CF1648 had no such elongation effect (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, when similar overexpression experiments were performed with V. cholerae using strains N16961(pSBΔ87) and N16961(pSBΔ189) (Table 1), both of the truncated proteins had cell elongation effects (Fig. 4B); however, the frequency of elongated cells was low either with CgtAΔ29 (∼10%) or with CgtAΔ62 (∼3%), while overexpression of full-length CgtA caused elongation in about 25% of V. cholerae cells. Thus, unlike the protein in E. coli, the truncated CgtAΔ62 protein appeared to be slightly functional. CF1648 and N16961, each carrying pSBORF, were used as controls, and they were grown in the presence or absence of arabinose (Fig. 4B). Taken together, the data appear to show that the overexpression effects (i.e., cell elongation) of truncated and full-length CgtA proteins of V. cholerae are distinctly different for the two organisms, which is currently not understood; thus, further investigation is needed to come to a definite conclusion.

FIG. 4.

Overexpression of whole and C-terminally truncated CgtA proteins and effects of these proteins on cell morphology. (A) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of arabinose (0.2%)-induced and uninduced total cellular proteins of V. cholerae cells. Arabinose-induced or uninduced cells were grown for 5 h at 37°C with shaking, and whole-cell lysates were prepared, which was followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis. Lane 1, N16961(pBAD24) without arabinose; lane 2, N16961(pBAD24) induced with arabinose; lane 3, N16961(pSBORF) grown without arabinose; lane 4, N16961(pSBORF) induced with arabinose; lane 5, N16961(pSBΔ87) induced with arabinose; lane 6, N16961(pSBΔ189) grown with arabinose; lane 7, protein molecular weight markers (sizes are indicated on the right). The arrows indicate overexpressed full-length CgtA protein (∼44 kDa [lane 4]) and its C-terminally truncated forms (∼41 and ∼38 kDa [lanes 5 and 6, respectively]). (B) Phase-contrast micrographs of E. coli strain CF1648 (top panels) and V. cholerae strain N16961 (bottom panels) overexpressing full-length CgtA using plasmid pSBORF or overexpressing C-terminally truncated CgtA proteins using plasmids pSBΔ87 and pSBΔ189. Cells were grown in LB with arabinose (+ ara) or without arabinose (− ara) for 5 h at 37°C with shaking.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Cashel, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, for the generous gift of E. coli strains CF1648 and CF1693. We thank Archana Bharti and Joubert Banjop Kharlyngdoh for their sincere help with this work.

S.S. and B.D. are grateful for research fellowships from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. This work was partially supported by research grant MLP110 from CSIR.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1989. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY.

- 2.Bomchil, N., P. Watnick, and R. Kolter. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Vibrio cholerae gene, mbaA, involved in maintenance of biofilm structure. J. Bacteriol. 1851384-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buglino, J., V. Shen, P. Hakimian, and C. D. Lima. 2002. Structural and biochemical analysis of the Obg GTP binding protein. Structure 101581-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiaramello, A. E., and J. W. Zyskind. 1990. Coupling of DNA replication to growth rate in Escherichia coli: a possible role for guanosine tetraphosphate. J. Bacteriol. 1722013-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das, B., and R. K. Bhadra. 2008. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae ΔrelA ΔspoT double mutants. Arch. Microbiol. 189227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutkiewicz, R., M. Slominska, G. Wegrzyn, and A. Czyz. 2002. Overexpression of the cgtA (yhbZ, obgE) gene, coding for an essential GTP-binding protein, impairs the regulation of chromosomal functions in Escherichia coli. Curr. Microbiol. 45440-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foti, J. J., J. Schienda, A. V. Sutera, Jr., and S. T. Lovett. 2005. A bacterial G protein-mediated response to replication arrest. Mol. Cell 17549-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foti, J. J., S. N. Persky, D. J. Ferullo, and S. T. Lovett. 2007. Chromosome segregation control by Escherichia coli ObgE GTPase. Mol. Microbiol. 65569-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1774121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haralalka, S., S. Nandi, and R. K. Bhadra. 2003. Mutation in the relA gene of Vibrio cholerae affects in vitro and in vivo expression of virulence factors. J. Bacteriol. 1854672-4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang, M., K. Datta, A. Walker, J. Strahler, P. Bagamasbad, P. C. Andrews, and J. R. Maddock. 2006. The Escherichia coli GTPase CgtAE is involved in late steps of large ribosome assembly. J. Bacteriol. 1886757-6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang, M., S. M. Sullivan, P. K. Wout, and J. R. Maddock. 2007. G-protein control of the ribosome-associated stress response protein SpoT. J. Bacteriol. 1896140-6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi, G., S. Moriya, and C. Wada. 2001. Deficiency of essential GTP-binding protein ObgE in Escherichia coli inhibits chromosome partition. Mol. Microbiol. 411037-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kok, J., K. A. Trach, and J. A. Hoch. 1994. Effects on Bacillus subtilis of a conditional lethal mutation in the essential GTP-binding protein Obg. J. Bacteriol. 1767155-7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kukimoto-Niino, M., K. Murayama, M. Inoue, T. Terada, J. R. H. Tame, S. Kuramitsu, M. Shirouzu, and S. Yokoyama. 2004. Crystal structure of the GTP-binding protein Obg from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J. Mol. Biol. 337761-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maddock, J., A. Bhatt, M. Koch, and J. Skidmore. 1997. Identification of an essential Caulobacter crescentus gene encoding a member of the Obg family of GTP-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 1796426-6431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnusson, L. U., B. Gummesson, P. Joksimovic, A. Farewell, and T. Nystrom. 2007. Identical, independent, and opposing roles of ppGpp and DksA in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1895193-5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiti, D., B. Das, A. Saha, R. K. Nandy, G. B. Nair, and R. K. Bhadra. 2006. Genetic organization of pre-CTX and CTX prophages in the genome of an environmental Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 strain. Microbiology 1523633-3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittenhuber, G. 2001. Comparative genomics of prokaryotic GTP-binding proteins (the Era, Obg, EngA, ThdF (TrmE), YchF and YihA families) and their relationship to eukaryotic GTP-binding proteins (the DRG, ARF, RAB, RAN, RAS and RHO families). J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 321-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Occhino, D. A., E. E. Wyckoff, D. P. Henderson, T. J. Wrona, and S. M. Payne. 1998. Vibrio cholerae iron transport: haem transport genes are linked to one of two sets of tonB, exbB, exbD genes. Mol. Microbiol. 291493-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto, S., M. Itoh, and K. Ochi. 1997. Molecular cloning and characterization of the obg gene of Streptomyces griseus in relation to the onset of morphological differentiation. J. Bacteriol. 179170-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto, S., and K. Ochi. 1998. An essential GTP-binding protein functions as a regulator of differentiation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 30107-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raskin, M. D., N. Judson, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2007. Regulation of stringent response is the essential function of the conserved bacterial G protein CgtA in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1044636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato, A., G. Kobayashi, H. Hayashi, H. Yoshida, A. Wada, M. Maeda, S. Hiraga, K. Takeyasu, and C. Wada. 2005. The GTP binding protein Obg homolog ObgE is involved in ribosome maturation. Genes Cells 10393-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sikora, A. E., R. Zielke, A. Wegrzyn, and G. Wegrzyn. 2006. DNA replication defect in the Escherichia coli cgtA(ts) mutant arising from reduced DnaA levels. Arch. Microbiol. 185340-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sikora, A. E., R. Zielke, K. Datta, and J. R. Maddock. 2006. The Vibrio harveyi GTPase CgtAv is essential and is associated with the 50S ribosomal subunit. J. Bacteriol. 1881205-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skorupski, K., and R. K. Taylor. 1996. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene 16947-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timson, J. 1975. Hydroxyurea. Mutat. Res. 32115-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vidwans, S. J., K. Ireton, and A. D. Grossman. 1995. Possible role for the essential GTP-binding protein Obg in regulating the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1773308-3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, J. D., G. M. Sanders, and A. D. Grossman. 2007. Nutritional control of elongation of DNA replication by (p)ppGpp. Cell 128865-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wout, P., K. Pu, S. M. Sullivan, V. Reese, S. Zhou, B. Lin, and J. R. Maddock. 2004. The Escherichia coli GTPase CgtAE cofractionates with the 50S ribosomal subunit and interacts with SpoT, a ppGpp synthetase/hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 1865249-5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao, H., M. Kalman, K. Ikehara, S. Zamel, G. Glaser, and M. Cashel. 1991. Residual guanosine 3′,5′ bispyrophosphate synthetic activity of relA null mutants can be eliminated by spoT null mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2665980-5990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]