Abstract

Background

The impact of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations in African adults on HAART has never been reported.

Methods

In 2004 in Abidjan, 106 adults on HAART had plasma viral load (VL) measurements. Patients with detectable VL had resistance genotypic tests. Patients were followed-up until 2006. Main outcomes were serious morbidity and immunological failure (CD4 count < 200/mm3).

Results

At study entry, the median previous time on HAART was 37 months and the median CD4 count 266/mm3; 58% of patients had undetectable VL, 20% detectable VL with no major resistance mutations, and 22% detectable VL with ≥1 major mutations. At study termination, 20% of patients had <200 CD4/mm3. Factors associated with immunological failure were a low baseline CD4 count (p=0.007) and ≥1 resistance mutations at baseline (p=0.04). Compared with patients with undetectable VL, those with detectable VL without mutations and those with ≥1 mutations had adjusted hazard ratios of immunological failure of 2.56 (95%CI 0.76–8.54) and 4.32 (1.38–13.57), respectively. In patients with undetectable VL and detectable VL without and with mutations, the median change in CD4 count between study entry and termination was +129/mm3, +51/mm3 and +3/mm3, respectively. One patient died. The 18-months probability of remaining free of morbidity was 0.79 in patients with undetectable VL and 0.69 in those with resistance mutations (p=0.19).

Conclusion

In this setting with restricted access to second-line HAART regimens, patients with major resistance mutations had higher rates of immunological failure, but most of them maintained stable CD4 count and stayed alive during 20 months.

Keywords: Adult; Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active; methods; CD4 Lymphocyte Count; methods; Cohort Studies; Cote d'Ivoire; epidemiology; Drug Resistance, Viral; genetics; Female; Genotype; HIV Infections; drug therapy; genetics; immunology; HIV-1; genetics; HIV-2; genetics; Humans; Male; Mutation; Treatment Outcome; Viral Load; methods

Introduction

At the end of 2005, the number of adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa was estimated at 810,000 [1]. This number is expected to increase rapidly within the near few years. In this context, the emergence of resistance to antiretroviral drugs should be watched closely [2].

So far, the rate of primary resistance to antiretroviral drugs has been found to be low in sub-Saharan Africa [3–5]. A few studies have suggested a rapid selection of drug resistance mutations after antiretroviral therapy initiation [6–8]. However, these investigations have been conducted in small number of settings only and/or have concerned a limited number of patients over a short period on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). In most sub-Saharan African settings where the access to HAART has been rapidly scaled-up over the past few years, little is known on the pattern of primary and secondary drug resistance

Data on antiretroviral drug resistance are needed to help experts to identify the most appropriate first-line and second-line regimens of HAART to be recommended in national and international guidelines. However, these guidelines will have to take into account not only the prevalence of primary and secondary resistance mutations in the population, but also the clinical and immunological consequences for patients of harboring resistant virus while being on a given HAART regimen. To our knowledge, these consequences have not been clearly described in the sub-Saharan African context.

In 2004, we performed viral load (VL) measurements and genotype resistance tests in adults who were receiving HAART in Abidjan. After virological assessments, we followed these patients under cohort conditions during 20 months. We describe here their clinical and immunological evolution over these 20 months, according to the presence or absence of mutations at the time of inclusion in the study.

Methods

Setting and Patients

From 1996 to 2003, 723 HIV-infected adults have been followed in the ANRS 1203 cohort study in Abidjan [9, 10]. At the end of this study, health professionals managing this cohort created a non-governmental association, ACONDA In 2004, ACONDA launched a five-year programme of access to HIV care and treatment in partnership with the Institute of Public Health, Epidemiology and Development (ISPED, Bordeaux, France). This program was funded by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), through the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF, Washington DC, USA). The follow-up procedures and the computerized data management system of the ACONDA/ISPED programme have been inspired from those of the ANRS 1203 cohort study [9, 10].

In July 2004, when the ACONDA/ISPED programme started, all adults who previously received HAART while being followed-up in the ANRS 1203 cohort study were offered a virological status assessment, including plasma VL measurements and genotype drug resistance testing. Patients included in the present study were all HIV-1 infected adults who started HAART in the ANRS 1203 cohort study and who continued to be followed-up in the ACONDA/ISPED programme when the ANRS 1203 study stopped. Baseline was the date of the blood sample collection for virological tests. The end of study date was March 31st 2006.

The ANRS 1203 cohort study and the ACONDA/ISPED programme database were approved by the National Ethics Committee of Cote d’Ivoire.

Follow-up

In the ACONDA/ISPED programme, patients on HAART have scheduled monthly clinical visits and bi-annual CD4 cell count measurements. In the interval between two visits, they have open access to their health centre. In accordance with the guidelines of the Côte d’Ivoire Ministry of Health, medical scheduled and unscheduled consultations, antiretroviral drugs, and bi-annual CD4 counts are provided under a monthly package price of 2 US$. For all non- antiretroviral drugs, patients are required to pay an additional package price of 1 US$ per drug prescription, irrespective of the number and type of drugs prescribed. Symptomatic patients are managed according to pre-defined standardized algorithms, including laboratory X-ray investigations and standardized first-line treatment regimens for most frequent syndromes [11]. For patients who don’t keep scheduled appointment, telephone calls or home visits are made by a community-based team, including experienced social workers and members of associations of people living with HIV [12]. For the present study, we used standardized forms to record baseline and follow-up socio-demographic and clinical data. All clinical events were reviewed by an event documentation committee. The diagnostic criteria were the same as those used in the ANRS 1203 cohort study [9–11].

Laboratory testing

CD4 count was measured by flow cytometry (True Count® technique on FAC Scan®, Becton Dickinson, Aalst-Erembodegem, Belgium) at the CeDReS laboratory, Treichville Hospital, Abidjan. Plasma HIV-1 RNA VL was quantified using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at the CeDReS laboratory (Taq Man technology Abi Prism 7000; Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland, limit of detection 300 copies/mL)[13]. For all patients with a detectable VL, genotype resistance testing was performed at the Projet RETRO-CI laboratory, Abidjan. For sequencing of the pol gen, HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma by the Quiagen method (Quiamp Viral RNA Mini Kit; Quiagen, Valencia, CA, U.S.A). The RNA was then used in a 2-step RT-PCR reaction. The resulting PCR product is 1,800 base pairs length. After purification with Microcon 100 columns (Millipore), the PCR products were sequenced using 6–7 primers and the Big Dye Terminator v1.1 chemistry. Excess dyes terminators were removed using ethanol/sodium precipitation. The sequencing reactions were runs on the ABI 3100 Genetic analyzer. Protease and RT sequences obtained were analysed for the presence of drug resistance mutations using the Viroseq™ Genotyping System Software v.2.5 and manually edited (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amino acid sequences were pair wise aligned to an HIV-1 HXB-2 K03455 reference sequence. Genotypic mixtures were reported as mutant when non-wild type nucleotide peaks were at least 20% of the total peak at a base [14].

In this study, any mutations that are listed in the October/November 2006 consensus from the International AIDS Society were considered [15] Mutations were classified as either major or minor. A strain was considered resistant in the presence of major drug resistance mutations. Major genotypic drug resistance mutations were the following: for nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs): T215Y/F, K70R, M184V, D67N, M41L, L210W, K219E/Q or T69D; for non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): K103N, P225H or L1001; and for protease inhibitors (PIs), L90M or I84V.

Statistical analysis

Outcomes were death of any cause, occurrence of any new serious morbidity event, and immunological failure. Serious morbidity events were all World Health Organisation (WHO) stage 3 or 4-classifying event, and all events leading to hospitalization or to death. Immunological failure was defined as a CD4 count below 200/mm3 at study termination. Patients were considered as “lost to follow-up” if their last contact with study team was prior to March 31st 2006 and no further information on vital status could be recorded from March 31st 2006 through September 31st 2006. The probability of survival and of remaining free of serious morbidity was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard regression models for first events were used to study the association between outcomes and baseline and follow-up characteristics.

Results

Patients Characteristics

Of the 723 patients who participated in the ANRS 1203 cohort, 195 started HAART before July 2004, including 54 who started HAART within the framework of a trial of structured treatment interruption of HAART (Trivacan trial) and 141 who started HAART within the framework of the Cotrame cohort. Among the latter, three were HIV-2 infected, and 32 died (n=20), were lost-to-follow-up (n=8) or were transferred out (n=4) before July 2004. The remaining 106 patients were alive and followed up in the ACONDA/ISPED programme in July 2004, and could be included in the present study. Their characteristics are shown in table 1. Their median nadir of CD4 count was 122/mm3 (interquartile range [IQR], 28–266). At study entry, their median previous time on HAART was 37.4 months, (IQR, 27.2–48.3). During the period on HAART preceding inclusion, 66 patients had 135 modifications in their HAART regimen, including 27 patients with only one modification, 18 with 2 modifications, and 21 with more than 2 modifications.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 106 patients included in the study

| Characteristics at HAART initiation | ||

| Women, number (%) | 63 | (59%) |

| Including with history of pMTCT* | 16 | (25%) |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 38 | (33–44) |

| Antiretroviral dual therapy before HAART initiation (number, %) | 7 | (7%) |

| Type of HIV seropositivity, number (%) | ||

| HIV-1 | 101 | (95%) |

| Dual HIV-l&2 | 5 | (5%) |

| Nadir of CD4+ cell count/mm3, median (IQR) | 122 | 58–226 |

| Body mass index in kg/m3, median (IQR) | 20.5 | (18.5–22.7) |

| WHO clinical stage III or IV, number (%) | 96 | (91%) |

| Past history of tuberculosis, number (%) | 15 | (14%) |

| Initial HAART regimen**, number (%) | ||

| 2 NRTIs + 1 PI | 61 | (58%) |

| 2 NRTIs + 1 NNRTI | 37 | (35%) |

| Others | 8 | (8%) |

| Characteristics at inclusion in the study | ||

| Previous time on HAART in months, median (IQR) | 37.4 | (27.2–48.3) |

| Drug regimen change since HAART initiation, number (%) | ||

| None | 40 | (38%) |

| Patients with one change | 27 | (25%) |

| Patients with ≥ 2 changes | 39 | (37%) |

| CD4+ cell count/mm3, median (IQR) | 266 | (159–407) |

| Body mass index in kg/m2, median (IQR) | 21.6 | (19.8–24.7) |

| WHO clinical stage III or IV, number (%) | 100 | (94%) |

| Past history of tuberculosis, number (%) | 25 | (24%) |

| Current HAART regimen***, number (%) | ||

| 2 NRTIs + 1 PI | 56 | (53%) |

| 2 NRTIs + 1 NNRTI | 47 | (45%) |

| Others | 2 | (2%) |

| Virological status | ||

| Undetectable viral load, number, (%) | 62 | (58%) |

| Detectable viral load, number (%) | 44 | (42%) |

| With ≥ 1 major mutations | 23 | (21%) |

| With no major mutations | 21 | (20%) |

| Follow-up after inclusion in the study | ||

| Follow-up time in months, median (IQR) | 20.5 | (19.7–21.1) |

| At least one serious clinical event during follow-up, number (%) | 29 | (27%) |

| Characteristics at study termination | ||

| CD4+ cell count/mm3, median (IQR) | 338 | (214–519) |

| Status, number (%) | ||

| Deceased | 1 | (1%) |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 | (1%) |

| Alive and in active follow-up | 104 | (98%) |

IQR: interquartile range;

HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy;

NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor;

NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor;

PI: protease inhibitor.

Viral load: plasma HIV-1 RNA level

WHO: World Health Organisation

pMTCT: prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection: ZDV (n=14), ZDV+NVP (n=l), d4T+3TC+NFV (n=l).

NRTIs: 3TC (n=76), ZDV (n=61), d4T (n=45), ddI (n=29), ddC (n=1); NNRTI: EFV (n=37); PI: IDV (n=30), NFV (n=29), SQV (n=2).

NRTIs: 3TC (n=79), ZDV (n=55), d4T (n=51), ddI (n=28); NNRTI: EFV (n=47); PI: IDV (n=29), NFV(n=28)

Viral load and resistance tests at study entry

At inclusion, 62 (58%) patients had undetectable viral load (VL) (< 300 copies/mL), and 44 (42%) detectable VL. There was no significant difference in VL distribution between patients with major genotypic drug resistance mutations and patient with no major mutations (median VL 3.7 log10 copies/ml, IQR 3.2–4.6, versus median VL 3.6 log10 copies/ml, IQR 3.1–4.4, p=0.52).

All patients’ strains with detectable VL could be amplified for HIV genotyping. Of the 44 patients with detectable VL, 21 had no major resistance mutations and 23 had ≥1 major resistance mutations. In all patients with detectable VL with no major resistance mutations, at least one minor mutation was detected. Table 2 details the patterns of minor mutations and major resistance mutations that were detected in the 44 patients with detectable VL. The most frequent major mutations were M184V (n=15), D67N (n=6), M41L (n=6), K103N (n=10) and L90M (n=3). The most frequent minor mutations were M36I (n=43), L10I/V/F (n=19), L63P (n=6), and A71V (n=5). Table 3 details, for each of the 23 patients with at least one major mutation, the mutations detected, the type of drugs and the number of drug-classes affected. Of the 23 patients with major mutations, 16 presented major mutations for one class and seven for two classes. No patient had major mutations affecting the three classes of drug. The only baseline factor found to be associated with the presence of at least one major mutation was a low CD4 count (Odds ratio of major mutation in patients with less than 200 CD4 cells/mm3 compared with other patients: 3.49; 95% CI 1.32–9.21; p=0.01).

Table 2.

Pattern of mutations in the 44 patients with detectable viral load at inclusion in the study

| Mutations | Mutations associated with resistance to: | Number of patients | Percentage of patients * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major mutations to NRTIs | |||

| M184V | 3TC | 15 | 14 |

| D67N | ZDV, d4T | 6 | 6 |

| M41L | ZDV, d4T | 6 | 6 |

| T215Y/F | ZDV, d4T | 4 | 4 |

| K70R | ZDV, d4T | 3 | 3 |

| L210W | ZDV, d4T | 2 | 2 |

| K219E/Q | ZDV, d4T | 2 | 2 |

| T69D | All NRTIs | 1 | 1 |

| Minor mutations to NRTIs | |||

| V118I | - | 1 | 1 |

| Major mutations to NNRTIs | |||

| K103N | EFV, NVP | 10 | 9 |

| P225H | EFV | 2 | 2 |

| L100I | EFV, NVP | 1 | 1 |

| Major mutations to PI | |||

| L90M | NFV, SQV | 3 | 3 |

| I84V | IDV, RTV | 1 | 1 |

| Minor mutations to PI | |||

| M36I | - | 43 | 40 |

| L10I/V/F | - | 19 | 18 |

| L63P | - | 6 | 6 |

| A71V | - | 5 | 5 |

| K20R | - | 2 | 2 |

| G73S | - | 1 | 1 |

| V77I | 1 | 1 | |

NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI: protease inhibitor; ZDV: zidovudine; ddI: didanosine; 3TC: lamivudine; NVP: nevirapine; EFV: efavirenz; NFV: nelfinavir; IDV: indinavir; SQV: saquinavir; APV: amprenavir; RTV: ritonavir; LPV/r: lopinavir/ritonavir.

Percentage of patients with the mutation among the 106 patients included in the study

Table 3.

Distribution of mutations in the 23 patients with major mutations at inclusion in the study

| Patient | Resistance mutations to NRTIs | Resistance mutations to NNRTIs | Resistance mutations to PIs | Number of classes * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M184V | None | None | 1 |

| 2 | M184V, M41L, D67N, L210W | None | None | 1 |

| 3 | M184V, M41L, T215Y, | None | None | 1 |

| 4 | M184V | None | None | 1 |

| 5 | M184V | None | None | 1 |

| 6 | M184V | None | None | 1 |

| 7 | D67N | None | None | 1 |

| 8 | M184V, M41L, K70R, D67N, K219Q | None | None | 1 |

| 9 | M184V | None | None | 1 |

| 10 | None | K103N | None | 1 |

| 11 | None | K103N | None | 1 |

| 12 | None | K103N | None | 1 |

| 13 | None | K103N, L100I | None | 1 |

| 14 | None | None | L90M | 1 |

| 15 | M41L | K103N | None | 2 |

| 16 | M184V, T215F, K70R, K219Q | K103N, P225H | None | 2 |

| 17 | M184V | K103N | None | 2 |

| 18 | M184V, T215Y | K103N | None | 2 |

| 19 | M41L, D67N, L210W | K103N | None | 2 |

| 20 | M184V | K103N, P225H | None | 2 |

| 21 | M184V | None | L90M | 2 |

| 22 | M184V, K70R, D67N | None | I84V | 2 |

| 23 | M184V, T215Y, T69D, M41L, D67N | None | L90M | 2 |

NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI: protease inhibitor

number of antiretroviral drug classes affected

Outcomes

After virological assessment, patients were followed-up for a median of 20.5 months. During follow-up, only 10 of the 23 patients with major resistance mutations experienced a change in their HAART regimen and received a new regimen containing only drugs for which no resistance were found in the genotype tests. Of the remaining 13 patients, 3 were still receiving their first-line regimen and 10 were already receiving a second-line regimen at the time of inclusion.

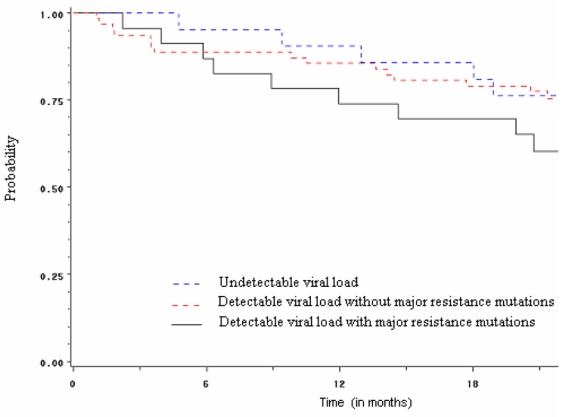

During follow-up after virological assessment, one patient was lost to follow-up and one patient died. These two patient harboured major resistance mutations. 29 patients (included 9 patients with major resistance mutations) experienced 43 new episodes of serious morbidity, including 11 patients with 17 oral candidiasis, six patients with eight severe bacterial events (pneumonia 3, enteritis 2, invasive urogenital infections 2, sinusitis 1), one patient with tuberculosis and 12 patients with 17 episodes of unexplained fever or unexplained enteritis leading to at least one day at hospital. As shown in figure 1, the 18-months probability of remaining alive and free of severe morbidity was 79% in patients with undetectable VL, versus 86% in patients with detectable VL without major resistance mutations (p=0.91) and 69% in patients with detectable VL with major resistance mutations at study entry (p=0.19), respectively. In the multivariate analysis, the presence of mutations at study entry was not significantly associated with the risk of serious morbidity during follow-up (adjusted Hazard Ratio 1.73, 95% 0.73–4.12, p=0.21)

Figure 1.

Probability of remaining alive and free of serious morbidity within time, according to virological status at inclusion

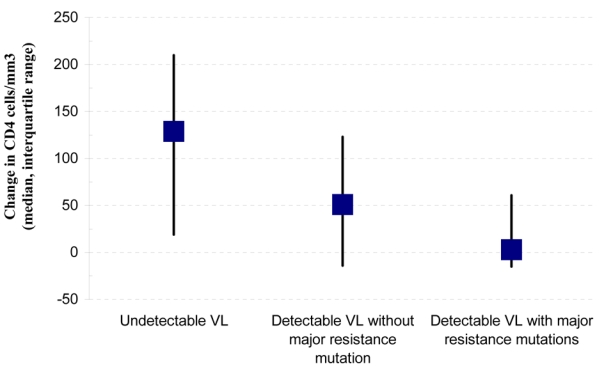

The median time between the end of study date and the date of the last available CD4 count was 2.6 months (IQR 0.8–3.7). The median gain in CD4 count between study entry and the date of this last available CD4 count was +75/mm3 overall, and +129/mm3, +5 1/mm3 and +3/mm3 in patients with undetectable VL, detectable VL without resistance mutations and detectable VL with resistance mutations at study entry, respectively (figure 2). In the multivariate analysis, the two variables significantly associated with immunological failure at the end of the study were a baseline CD4 cell count < 200/mm3 and the presence of major resistance mutations at study entry (table 4).

Figure 2.

Change in CD4 cell count between inclusion and study termination, according to virological status at inclusion

VL: viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA level)

Table 4.

Factors associated with immunological failure at study termination

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P | |

| Characteristics at inclusion | ||||||

| Sex (men vs. women) | 0.45 | (0.18–1.10) | 0.08 | 0.50 | (0.20–1.24) | 0.13 |

| Age (≥ 38 years vs. < 38 years) | 1.35 | (0.55–3.30) | 0.51 | - | - | - |

| History of pMTCT before HAART (Yes vs. No) | 0.40 | (0.05–2.99) | 0.37 | - | - | - |

| History of ARV dual-therapy before HAART (Yes vs. No) | 0.92 | (0.12–6.88) | 0.93 | - | - | - |

| CD4 nadir ≤ 50/mm3 (Yes vs. No) | 2.92 | (1.19–7.17) | 0.02 | 1.68 | (0.64–4.39) | 0.29 |

| Time on HAART before inclusion (≥ 3 years vs. < 3 years) | 1.32 | (0.59–3.00) | 0.50 | - | - | - |

| History of tuberculosis before inclusion (Yes vs. No) | 1.78 | (0.71–4.47) | 0.21 | 0.91 | (0.35–2.37) | 0.84 |

| CD4 at inclusion ≤ 200/mm3 (Yes vs. No) | 9.36 | (2.74–32.02) | < 0.001 | 6.02 | (1.61–22.5) | 0.008 |

| Virological status at inclusion (Ref: undetectable VL) | < 0.001 | 0.04 | ||||

| Detectable VL without Major resistance mutations | 4.05 | (1.24–13.29) | 0.02 | 2.58 | (0.77–8.64) | 0.12 |

| Detectable VL with Major resistance mutations | 8.07 | (2.7–24.16) | < 0.001 | 4.39 | (1.38–13.93) | 0.01 |

| Events during follow-up | ||||||

| At least one new serious morbidity event * (Yes vs. No) | 1.18 | (0.47–2.97) | 0.72 | - | - | - |

VL: viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA level); HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; ARV: antiretroviral; Ref: reference; pMTCT: prevention of mother–to-child transmission of HIV infection;

Any WHO stage 3 or 4-classifying event and any event leading to hospitalisation or death

Discussion

Data on the clinical consequences for patients of harboring resistant virus while being on HAART have never been reported in Africa.

Among our patients on HAART since a median of three years in Abidjan, 58% had undetectable VL, 20% had detectable VL with no major resistance mutations and 22% had major drug resistance mutations. Within the following 20 months, patients with major mutations had higher rates of immunological failure and tended to have higher rates of serious morbidity, but their CD4 count remained stable and only one of them died.

These findings deserve the following comments.

In our population, one out of five patients harbored major resistance mutations after a median time on HAART of three years. This rate is in the lower bracket of those previously reported from other sub-Saharan African settings, in patients with similar or shorter time on HAART [4, 6–8, 16–18]. Differences between African settings in term of rate of patients with resistance mutations may depend on various determinants. Our study did not aim at identifying these determinants, which still remain to be carefully studied.

The main objective of our study was to analyze the association between the presence of resistance mutations and treatment outcomes. To our knowledge, this has never been done in sub-Saharan Africa so far. Studies of outcomes in patients with resistance mutations are likely to reach different conclusions depending on the type and number of drugs affected and on the range of drugs available in a given setting. In industrialized countries, some studies found an association between drug resistance mutations and an increased risk of death or new AIDS-defining event/death [19, 20], whereas others did not found any association between drug resistance mutations and clinical outcomes [21, 22]. In Abidjan during the study period, the number of available antiretroviral drugs was limited. Several large programmes of access to HAART were being launched, but the country was experiencing a severe political crisis. In this context, only 43% of patients with major resistance mutations at baseline experienced a change in their HAART regimen and had a chance that a consecutive reduction in viral load could lead to better immunological and clinical outcomes. The remaining 57% of patients with major resistance could not have their drug regimen appropriately adapted to the genotype tests results during the study period. The consequences were the followings. On the one hand, the 20-months clinical and immunological outcomes of patients with resistance at baseline were clearly compromised as compared with patients with no resistance. On the other hand, these patients with resistance mutations had reasonable VL values at baseline (median 3.7 log10 copies/ml). During the 20-months follow-up, their CD4 count remained stable and close to 200/mm3. Though they tended to have higher morbidity rates, most were curable diseases, and only one patient died. In other words, their medium-term outcomes were impaired compared to patients without resistance mutations, but their antiretroviral treatment still protected them from immunological breakdown. The main reason for this is probably that they continued to receive at least one or two antiretroviral drugs against which their viruses had no resistance. Other reasons could be the poorer capacity of replication of resistant virus compared with wild type viruses [23, 24], and the preservation of some in vivo effects of some drugs on viruses showing in vitro resistance [25, 26]. In patients with virological failure, even a limited reduction in viral load has been shown to be of importance [27]..

Our study has the following limitations. First, patients who participated in the study were part of a group of patients who started HAART while they were followed in a cohort study between 1998 and 2003. Patients from this cohort who died or who were lost to follow-up before July 2004 could not be included in the present study. Among these patients, the rate of resistance mutations was unknown. Therefore, our conclusion that there is immunological stability among the patients with resistance mutations cannot apply to all patients who started HAART, but only to patients who survived and remained in care during a median of 37 months after HAART initiation. Second, our study included patients receiving different regimens of HAART and with different histories of regimen modification since HAART initiation. Our sample size was too limited to adjust the analysis of the association between resistance and outcomes on these variables. Further studies comparing outcomes in patients with and without resistance mutations should include a sufficient number of patients to allow adjustment on antiretroviral drugs received by the patients. Third, in our study, viral load was only measured at baseline and adherence to HAART was not measured. In further studies, viral load and adherence evolution should be carefully recorded. In patients with detectable viral load but no major resistance mutation and in those with major resistance who experience a change in their HAART regimen, the rate of virological success would be likely to be associated with improved adherence. Our findings have the following consequences on “when to change a failing regimen” in sub-Saharan Africa.

In settings where resistance tests are routinely available, drugs can be spared by an early selective substitution of the drugs against which the virus strains have been shown to be resistant through genotype tests. In sub-Saharan Africa, while CD4 measurement is becoming increasingly available, VL measurement is still rarely available, and genotype resistance tests are almost never available. Within the following years, millions of sub-Saharan African adults will receive HAART. In these patients, changing regimen for treatment failure will have to be based on clinical outcomes, with the help of CD4 counts in most settings and of VL measurements in some settings. In these patients, the timing of acquisition of resistance mutations and the number of mutations will be impossible to determine. Failing therapeutic regimens will be maintained during incompressible periods of time, thus increasing drug resistances [28, 29]. In this context, the decision of when to change a failing regimen should not be based on the possibility of sparing some drugs of the failing regimen, but should only focus on the risk for a patient to continue a given failing regimen until an entirely new regimen can be proposed to him. Our data suggest that most patients with major drug resistance mutations might maintain stable CD4 cell count and stay alive for more than one year. In low resource settings with restricted access to second-line ARV regimens, the decision to change a failing regimen could be taken within months. This should be taken into account in further cost-effectiveness analyses of HAART in sub-Saharan Africa [30].

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) via the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatrics AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), and by the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA et les Hépatites Virales, Paris, France (ANRS 1203).

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic; Geneva. 2006. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2006GlobalReport/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nkengasong JAN, Adje-Toure C, Weidle PJ. HIV antiretroviral drug resistance in Africa. AIDS Rev. 2004;6:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toni T, Masquelier B, Bonard D, et al. Primary HIV-1 drug resistance in Abidjan (Cote d’Ivoire): a genotypic and phenotypic study. AIDS. 2002;16:488–491. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200202150-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vergne L, Kane CT, Laurent C, et al. Low rate of genotypic HIV-1 drug-resistant strains in the Senegalese government initiative of access to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17 (Suppl 3):S31–38. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellocchi MC, Forbici F, Palombi L, et al. Subtype analysis and mutations to antiviral drugs in HIV-1-infected patients from Mozambique before initiation of antiretroviral therapy: results from the DREAM programme. J Med Virol. 2005;76:452–458. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adje C, Cheingsong R, Roels TH, et al. High prevalence of genotypic and phenotypic HIV-1 drug-resistant strains among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:501–506. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vergne L, Malonga-Mouellet G, Mistoul I, et al. Resistance to antiretroviral treatment in Gabon: need for implementation of guidelines on antiretroviral therapy use and HIV-1 drug resistance monitoring in developing countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:165–168. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200202010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weidle PJ, Malamba S, Mwebaze R, et al. Assessment of a pilot antiretroviral drug therapy programme in Uganda: patients’ response, survival, and drug resistance. Lancet. 2002;360:34–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seyler C, Anglaret X, Dakoury-Dogbo N, et al. Medium-term survival, morbidity and immunovirological evolution in HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:385–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anglaret X, Messou E, Ouassa T, et al. Pattern of bacterial diseases in a cohort of HIV-1 infected adults receiving cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2003;17:575–584. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anglaret X, Dakoury-Dogbo N, Bonard D, et al. Causes and empirical treatment of fever in HIV-infected adult outpatients, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2002;16:909–918. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200204120-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anglaret X, Toure S, Gourvellec G, et al. Impact of vital status investigation procedures on estimates of survival in cohorts of HIV-infected patients from Sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:320–323. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouet F, Ekouevi DK, Chaix ML, et al. Transfer and evaluation of an automated, low-cost real-time reverse transcription-PCR test for diagnosis and monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in a West African resource-limited setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2709–2717. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2709-2717.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bile EC, Adje-Toure C, Borget MY, et al. Performance of drug-resistance genotypic assays among HIV-1 infected patients with predominantly CRF02_AG strains of HIV-1 in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. J Clin Virol. 2005;32:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: Fall 2006. Top HIV Med. 2006;14:125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard N, Juntilla M, Abraha A, et al. High prevalence of antiretroviral resistance in treated Ugandans infected with non-subtype B human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:355–364. doi: 10.1089/088922204323048104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurent C, Kouanfack C, Vergne L, et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance and routine therapy, Cameroon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1001–1004. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.050860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferradini L, Jeannin A, Pinoges L, et al. Scaling up of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a rural district of Malawi: an effectiveness assessment. Lancet. 2006;367:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaccarelli M, Tozzi V, Lorenzini P, et al. Multiple drug class-wide resistance associated with poorer survival after treatment failure in a cohort of HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2005;19:1081–1089. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000174455.01369.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogg RS, Bangsberg DR, Lima VD, et al. Emergence of Drug Resistance Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Death among Patients First Starting HAART. PLoS Med. 2006;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030356. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas GM, Gallant JE, Moore RD. Relationship between drug resistance and HIV-1 disease progression or death in patients undergoing resistance testing. AIDS. 2004;18:1539–1548. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131339.68666.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machouf N, Thomas R, Nguyen VK, et al. Effects of drug resistance on viral load in patients failing antiretroviral therapy. J Med Virol. 2006;78:608–613. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deeks SG, Barbour JD, Martin JAN, Swanson MS, Grant RM. Sustained CD4+ T cell response after virologic failure of protease inhibitor-based regimens in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:946–953. doi: 10.1086/315334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cozzi-Lepri A, Phillips AN, Miller V, et al. Changes in viral load in people with virological failure who remain on the same HAART regimen. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Picado J, Savara AV, Sutton L, D’Aquila RT. Replicative fitness of protease inhibitor-resistant mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:3744–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3744-3752.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deeks SG, Wrin T, Liegler T, et al. Virologic and immunologic consequences of discontinuing combination antiretroviral-drug therapy in HIV-infected patients with detectable viremia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledergerber B, Lundgren JD, Walker AS, et al. Predictors of trend in CD4-positive T-cell count and mortality among HIV-1 -infected individuals with virological failure to all three antiretroviral-drug classes. Lancet. 2004;364:51–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kantor R, Shafer RW, Follansbee S, et al. Evolution of resistance to drugs in HIV-1-infected patients failing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2004;18:1503–1511. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131358.29586.6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goetz MB, Ferguson MR, Han X, et al. Evolution of HIV Resistance Mutations in Patients Maintained on a Stable Treatment Regimen After Virologic Failure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;15(43):541–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000245882.28391.0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldie SJ, Yazdanpanah Y, Losina E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV treatment in resource-poor settings-the case of Cote d’Ivoire. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1141–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]