Abstract

The association between sexual debut timing and depressive symptomatology in adolescence and emerging adulthood was examined using data from Waves I, II and III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Respondents who reported never having sexual intercourse at Wave I and were 18–22 years of age at Wave III were included (n=5,061). Twenty percent of respondents experienced early (<age 16) and 49% experienced typical (ages 16–18) sexual debut. In bivariate analyses, pre-debut depressive symptoms were associated with earlier sexual debut among female but not male adolescents. In models adjusting for demographic characteristics and pre-debut depressive symptoms, sexual debut was positively related to adolescent (Wave II) depressive symptomatology, but only among female adolescents age less than sixteen. However, sexual debut timing was unassociated with emerging adult (Wave III) depressive symptomatology for both male and female respondents. Findings suggest sexual debut timing does not have implications for depressive symptomatology beyond adolescence.

Keywords: Sexual initiation, longitudinal, depression, sex differences

The claim that adolescent sexual activity causes psychological harm has been used as one key rationale for current U.S. reproductive health policies (Golden, 2006). Advocates of abstinence-only policies cite research which has found that, compared with abstainers, adolescents who have experienced sexual debut are more likely to use substances, have lower academic achievement and aspirations, and experience poorer mental health (Billy, Landale, Grady, & Zimmerle, 1988; Burge, Felts, Chenier, & Parrillo, 1995; Hallfors et al., 2004). As in later life, adolescent sexual activity may lead to unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Over the last decade there have been significant decreases in the percentages of adolescents who had ever had intercourse, and in the teenage pregnancy rate (CDC, 2006; Santelli, Morrow, Anderson, & Lindberg, 2006). Despite these significant population changes, nearly half of persons in the U.S. initiate sexual activity before the end of high school, and over 90 percent by the time they reach young adulthood (Abma, Martinez, Mosher, & Dawson, 2004; C. T. Halpern, Waller, Spriggs, & Hallfors, 2006). If claims about the health risks posed by adolescent sexual debut are correct, one might expect a cascade of negative consequences into emerging adulthood. In the present study, we explored this possibility in relation to depression.

Potential linkages between adolescent sexual debut and depression are of particular interest. Well-established and enduring sex differences in depression begin in adolescence, and even moderate levels of depressive symptoms are associated with reduced functioning (Lewinsohn, Soloman, Seeley, & Zeiss, 2000). Investigation of the association between sexual debut and depression has been contentious, with different analyses supporting opposite-causal directions, suggesting the possibility of a bi-directional relationship. Some researchers have hypothesized that adolescents initiate sexual intercourse in an attempt to “self-medicate” an underlying mental health issue, for example, to alleviate feelings of isolation common to depression (Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford, & Halpern, 2005). Longmore et al. examined this question using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) (Longmore, Manning, Giordano, & Rudolph, 2004). Specifying depression on a continuous scale, and employing controls for self-esteem, age, race/ethnicity, parent income, dating status, parent education, and family structure, the authors found that baseline depressive symptoms predicted adolescent sexual initiation within a one-year follow-up among both male and female adolescents, although associations diminished in strength with age among female adolescents.

Also using Add Health data, Hallfors et al. produced somewhat contradictory findings (Hallfors et al., 2005). These authors used a dichomotized indicator for high depressive symptomatology as the predictor, and specified the outcome as clusters of health risk behaviors including alcohol use, cigarette use, drug use, number of sexual partners, and risky sexual behavior (e.g., exchanging sex for drugs or money). After controlling for age, race/ethnicity, parent education, family structure, and perceived physical maturity, they found that, among adolescents who reported none of the risk behaviors at baseline (i.e., Abstainers), baseline depressive symptoms did not significantly predict movement to any of the risk behavior clusters within a one-year follow-up for boys, and were actually associated with a lower risk of transition to very high risk clusters among girls. However, given that the outcome studied was not limited to sexual initiation, it is unclear whether these results indicate no relationship between depressive symptoms and sexual initiation in particular.

Other researchers have postulated that depression is a consequence of sexual initiation, because sexual activity during adolescence is generally thought to be inappropriate (Smith, 2005), and often accompanied by negative changes in relationships with parents and other conventional institutions (Ream, 2006). Hallfors et al. also investigated this hypothesis and found that, after controlling for high baseline depressive symptomatology, initiation of adolescent risk behaviors (including sexual activity), as indicated by risk cluster membership, was associated with depression at one year follow-up (Hallfors et al., 2005). Although there were a couple of exceptions (i.e., boys in the marijuana and high marijuana and sex clusters), these associations existed only for girls and were especially strong for girls in the highest risk clusters. Although not directly comparable, a more recent study by Meier (2007) also found that sexual debut was associated with depressive symptoms at one-year follow-up, but only for female adolescents who debuted before age 16 or whose relationships were short-lived after sexual initiation (Meier, 2007). Together these findings suggest that the effects of debut on adolescent depressive symptoms may be specific to girls, and, according to the Meier study, debut at a young age.

The findings from the Meier (2007) study are consistent with expectations derived from a Vulnerability – Stress Model of depression (Hyde, Mezulis, & Abramson, 2008). In this model, affective (e.g., negative emotionality), biological (e.g., genetic factors, early puberty), and/or cognitive risk factors (e.g., ruminative cognitive style), in interaction with negative life events, increase the likelihood of depression, especially for girls. Female adolescents typically place greater value on relationships in general (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000) and are also more likely to have negative perceptions/feelings about their first intercourse experience (Guggino & Ponzetti, 1997). If female adolescents are more likely than male adolescents to perceive their first intercourse experience (or its subsequent relationship outcome) as a negative life event, then, in the context of factors such as those noted above, sexual debut could lead to depressive symptoms.

The findings above suggest a link between sexual debut and adolescent depressive symptoms, at least under some circumstances. However, it is unclear whether sexual debut timing may relate to later life depressive symptomatology. Developmental transitions, including sexual intercourse initiation, have the potential to have lasting consequences for subsequent developmental trajectories and health (Elder, 1998; McLeod & Almazan, 2003). How earlier life experiences and later health are connected, however, varies across different models. For example, linear models of development postulate “that early experiences and competencies have continued influence over the life course regardless of subsequent events” (McLeod & Almazan, 2003). Alternately, contingency and transactional models approach development as a dynamic interactive process, assuming that the developing person, the experience of individual agency, and changing environmental supports can alleviate or exacerbate disadvantages from prior negative developmental transitions (McLeod & Almazan, 2003).

One relevant linear model of development is the stage termination hypothesis. According to this perspective, early initiation of developmental transitions can cause disruptions in functioning because the individual has not adequately mastered the skills necessary to navigate the new transition successfully (Petersen & Taylor, 1980). In the case of sexual debut, individuals who initiate early may not have the capacity for anticipating the potential consequences of sexual activity, and therefore inadequately protect themselves from these potential consequences. For example, it has been suggested that young adolescents do not have the cognitive maturity to plan for or adhere to health regimens that may be necessary to protect against sexual activity consequences (i.e., pregnancy or STDs) or to cope with relationship breakdown after sexual debut (Brooks-Gunn & Graber, 1994; Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Galen, 1998). Evidence consistent with this hypothesis can be found in the lower rates of condom use and higher rates of unintended pregnancy and STD infection among those who experience early compared to later sexual debut (Mosher & McNally, 1991; O’Donnell, O’Donnell, & Stueve, 2001; Upchurch, Mason, Kusunoki, Johnson, & Kriechbaum, 2004), and the association between relationship dissolution and later depression (Meier, 2007). In addition, clinical evidence supports significant continuity between adolescent-onset and later life depression (Aalto-Setala, Marttunen, Tuulio-Henriksson, Poikolainen, & Lonnqvist, 2002). Depression itself can lead to negative events, such as seeking out inappropriate relationships, which in turn feed back to the depression (Hankin & Abramson, 2001). Therefore, consistent with a linear model of development, it is possible that depressive episodes precipitated by sexual initiation could impact mental health outcomes beyond adolescence.

On the other hand, there are also theoretical and clinical reasons to hypothesize that sexual debut timing and mental health in emerging adulthood will not necessarily be related, or may be related in non-obvious ways. Normative developmental transitions often cause stress and discomfort, especially if multiple transitions occur at about the same time (Graber & Brooks-Gunn, 1996). However, consistent with the possibilities proposed in transactional models of development, most persons eventually acclimate to their new developmental status and resume normative functioning (Graber et al., 1998). Given that sexual initiation is statistically normative during adolescence, associations with depressive symptoms in other studies across a relatively brief period may be transitory, especially if subsequent relationships are positive experiences. Differences in individual vulnerability or resilience (as noted in the Vulnerability – Stress Model), in combination with positive contextual resources or lack thereof, determine psychosocial reorganization in response to new challenges and experiences (Curtis & Cicchetti, 2003). Further, clinical evidence indicates that episodic depressive symptoms during adolescence are less likely than persistent adolescent depressive symptoms to be associated with depression recurrence in emerging adulthood (Steinhausen, Haslimeier, & Metzke, 2006). Therefore, if the depressive symptoms elicited by sexual initiation represent a more episodic form of depression, one might expect no relationship between adolescent sexual initiation and emerging adult depressive symptoms.

The present study

The primary purpose of this study was to better understand the developmental and health implications of the timing of sexual debut by examining whether the timing of sexual debut is related to depressive symptomatology beyond adolescence. This study builds on prior studies that have only examined depressive symptom outcomes within a short (approximately one-year) period after sexual debut. Given some contradictions in the literature regarding the relationship between adolescent sexual debut and pre-existing depressive symptomatology, we began by testing the necessity of controlling for baseline depressive symptomatology.

H1a. Baseline depressive symptoms will be positively related to earlier compared to later subsequent sexual debut, but only among female adolescents.

H1b. Baseline depressive symptomatology will be positively associated with later depressive symptoms.

We expected that baseline depressive symptomatology would be significantly associated with both an earlier timing of sexual debut among female adolescents and later depressive symptomatology. Such expectations were consistent with the one study specifically examining the relationship between depressive symptoms and subsequent sexual debut (Longmore et al., 2004), with most prior studies documenting significant continuity between adolescent and adult depression, and with the Vulnerability – Stress Model. Our sex-specific hypothesis was based on the observation in the Longmore et al. study that only among female adolescents did the association between depressive symptomatology and subsequent debut decrease with age.

We also explored the relationship between adolescent sexual debut and subsequent depressive symptomatology during adolescence, because there have been contradictory findings regarding this association. Further, such analyses could provide empirical support for age cutoffs for what may be considered “early” sexual debut.

H2. Sexual debut between Waves I and II will be positively related to depressive symptoms at Wave II only among female adolescents age less that 16.

This hypothesis was consistent with the one study specifically examining differences according to relative sexual debut timing (Meier, 2007).

The main study hypothesis was:

H3. Sexual debut timing will be unrelated to depressive symptomatology in emerging adulthood for both male and female participants.

This hypothesis was based on a transactional model of development. That is, we propose that barring significant stress-vulnerability and a series of negative life events that perpetuate long-term depressive symptoms, most individuals who experienced depressive symptoms in the short term were expected to acclimate to and move beyond immediate consequences.

METHODS

Data

Data from Waves I, II and III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) contractual dataset were analyzed. Add Health is a nationally representative survey of U.S. adolescents enrolled in grades seven through twelve in the 1994–95 school year (Wave I); a more detailed description of the sampling procedures and study design can be found elsewhere (Harris, Florey, Tabor, & Udry, 2003). Over 90,000 adolescents in 132 schools participated in the Wave I in-school survey, with 20,745 also completing subsequent in-depth home interviews (1994–95 school year). Wave II follow-up home interviews with 14,738 Wave I in-home participants were conducted approximately one year later (1995–96 school year); Wave III follow-up interviews (n=15,170) were conducted approximately seven years after Wave I, in 2001.

Inclusion criteria for the present analysis were participation in all three waves and availability of Wave III sample weights (n=10,828), Wave I report of never having vaginal sexual intercourse (n=7,012), age of 18 to 22 years at Wave III (n=5,384), and complete data on all variables of interest (n=5,061). Restriction of the sample to those who debuted after Wave I was necessary to ascertain the temporal order of depressive symptoms and sexual debut, given past findings of depressive symptoms predicting sexual debut (Longmore et al., 2004). Exclusion of persons older than 22 at Wave III was necessary because persons age 23 and older who reported never having sexual intercourse at Wave I were not eligible to be part of the earliest debut timing group. Further, we wished to avoid issues of sample selectivity that would occur in older age groups where sexual debut prior to Wave I would be more common.

Measures

Outcome variables

To assess depressive symptomatology, Add Health utilized a modified version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. The original 20-item CES-D inquires about the past week frequency of 20 depressive symptoms, reported on a zero (rarely or never) to three (most or all of the time) scale. Respondents were asked 18 of the original 20 depressive symptom items at Waves I and II, and nine of the original 20 items at Wave III. To create comparable depressive symptom scores at all waves (so that baseline depressive symptoms scores could be controlled for), only the nine items asked at all three waves were included in the summary score. This subset included past week frequency of feeling bothered by things, inability to shake the blues, feeling as good as others, having trouble keeping one’s mind on what one is doing, feeling depressed, feeling tired, enjoying life, feeling sad, and feeling disliked. After reverse coding positively-worded items, the summary score was created by adding the responses to the nine items, producing a score between 0 and 27 (Wave I Cronbach’s α = 0.79, Wave II Cronbach’s α = 0.80, Wave III Cronbach’s α = 0.80). Summary scores were calculated only if all nine constituent items were non-missing.

The CES-D has been used as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder in adolescent populations. On the full 20-item scale (score range 0 to 60), cut points of 22 for adolescent males and 24 for adolescent females have been found to maximize sensitivity and specificity for this disorder (Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991). In the current analysis, proportionately adjusted cut points of 10 for male participants and 11 for female participants were used to create a dichotomous indicator of likely clinically significant depressive symptom levels. Classification based on the nine items was found to be 94% consistent with classification based on the 18 items available at Wave I interview, indicating considerable overlap with a more complete CES-D scale (results available from authors on request).

Independent variables

For analyses assessing associations between sexual debut and short-term depressive symptom outcomes (i.e., depressive symptom outcomes at Wave II), a dichotomous indicator for sexual debut between Wave I and II was constructed. This indicator was based on the respondent’s report of ever having had vaginal sexual intercourse (yes/no) at Wave II. Because the analytic sample was restricted to those who had not initiated vaginal sexual intercourse by Wave I, an affirmative response to this question indicates sexual debut between Waves I and II.

In analyses examining the association between sexual debut timing and emerging adult (Wave III) depressive symptom outcomes, sexual debut timing was derived from Wave III self-report of age in years when the respondent first had vaginal sexual intercourse. Use of the Wave III report was necessary to accurately classify relative debut timing for those respondents who initiated vaginal sexual activity after their last adolescent interview (Wave II). Using the entire Wave III sample (n=14,322), we examined the distribution of reported ages at first sexual intercourse; we then attempted to divide this distribution into equal thirds, such that 1/3 of respondents would be in the “early” category, 1/3 in the “typical” category, and 1/3 in the “late” category. Perfect division into thirds was not possible, however, because of a tight clumping of respondents who reported debut between ages 16–18. The final categorization specified “early” debut as debut between ages of 10–15, “typical” as those aged 16–18 at debut, and “late” as those aged >18 at debut and those reporting never having sexual intercourse by Wave III. Separate categorization by gender was not necessary, because the boundaries for debut timing categories for male and female participants were the same.

Control variables

There are a number of factors that have been empirically associated with both the timing of sexual debut and depressive symptoms. These include sociodemographic factors as well as other individual differences (e.g., pubertal timing, intelligence/achievement, religiosity, parent and school connectedness, and various personality dimensions). For parsimony, we began by using only sociodemographic factors and Wave I depression as controls, with the plan to expand the number of controls if appropriate. Therefore, covariates included race (White, Black, Other) (Sen, 2004; Upchurch, Levy-Storms, Sucoff, & Aneshensel, 1998), Hispanic ethnicity (yes or no) (Sen, 2004; Upchurch et al., 1998), living arrangement (with both biologic parents, stepfamily, single parent, other) (Barrett & Turner, 2005; Capron, Therond, & Duyme, 2007; Miller, 2002), parental education (higher of either mother or father: less than high school diploma, high school diploma/GED, some postsecondary, bachelors degree or more) (Barrett & Turner, 2005; Santelli, Lowry, Brener, & Robin, 2000) as well as the Wave I pre-debut high depressive symptomatology indicator (Aalto-Setala et al., 2002; Longmore et al., 2004). Age at Wave I was included as a control variable and was examined as a potential modifier for analyses examining associations between debut between Waves I and II and Wave II depressive symptomatology. Age at Wave III interview was included as a control variable in analyses examining associations between sexual debut timing and Wave III depressive symptomatology.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted in Stata 9.2, using survey commands to adjust for complex survey design and weighted to yield population estimates. All bivariate and multivariable analyses were performed stratified by biological sex, given past findings of sex differences in the association between sexual activity and depressive symptoms (Waller et al., 2006). Descriptive statistics (unweighted sample sizes and weighted proportions) were generated to characterize sample sociodemographic characteristics, as well as the distribution of sexual debut timing and depressive symptomatology. To test the association between baseline depressive symptoms and timing of sexual debut (Hypothesis 1a), chi-square analyses were employed. Tests of the relationship between baseline and later depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 1b) were incorporated in analyses for Hypotheses 2 and 3. To characterize the association between sexual debut and short-term depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 2), we used multivariable logistic regression models, including the dichotomous indicator for debut between Waves I and II, sociodemographic and Wave I depressive symptomatology control variables, and an interaction between Wave I age and the sexual debut indicator. Finally, to investigate associations between sexual debut timing and emerging adult depressive symptom outcomes (Hypothesis 3), bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed including sociodemographic and Wave I depressive symptom control variables, as well as sexual debut timing indicator variables.

RESULTS

Results from descriptive analyses are presented in Table 1. As per the sample inclusion criteria, the age of respondents at Wave III ranged from 18 to 22; 25.2% were ages 18–19, 54.0% were ages 20–21, and 20.8% were 22 years old. The majority of the sample reported their race as white (76.8%), with 10.3% reporting their race as black and 12.9% reporting another race. Slightly over 10% of the analytic sample reported Hispanic ethnicity. The majority of respondents reported living with both biologic parents (64.0%) and having at least one parent with some college education or greater (61.1%). Sexual debut during adolescence was common –20% initiated sexual intercourse early in adolescence, 49% experienced typical debut timing, and 31% debuted after adolescence or had not experienced intercourse by Wave III. The prevalence of high depressive symptomatology was significantly higher for female participants than for male participants at all three waves.

Table 1.

Prevalence of demographic characteristics, high depressive symptomatology, and sexual debut timing in the study population

| Full Sample (n=5,061)

|

Female participants (n=2,830)

|

Male participants (n=2,231)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Weighted % (95% CI) | n | Weighted % (95% CI) | n | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Wave III age | ||||||

| 18–19 | 1,087 | 25.2 (21.7 – 29.1) | 642 | 26.2 (22.2 – 30.7) | 445 | 24.1 (20.4 – 28.2) |

| 20–21 | 2,626 | 54.0 (51.9 – 56.0) | 1,504 | 54.0 (51.5 – 56.4) | 1,122 | 53.9 (50.7 – 57.1) |

| 22 | 1,348 | 20.8 (16.9 – 25.4) | 684 | 19.8 (15.9 – 24.4) | 664 | 22.0 (17.5 – 27.2) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 3,356 | 76.8 (72.1 – 81.0) | 1,848 | 76.6 (71.8 – 80.8) | 1,508 | 77.0 (71.8 – 81.6) |

| Black | 896 | 10.3 (7.8 – 13.6) | 576 | 11.6 (8.7 – 15.4) | 320 | 8.9 (6.4 – 12.2) |

| Other | 809 | 12.9 (10.2 – 16.1) | 406 | 11.8 (9.3 – 14.7) | 403 | 14.1 (10.8 – 18.1) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 657 | 10.5 (7.8 – 14.0) | 359 | 10.6 (7.8 – 14.3) | 298 | 10.4 (7.4 – 14.3) |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Two biologic parents | 3,172 | 64.0 (61.7 – 66.3) | 1,731 | 63.1 (60.3 – 65.8) | 1,441 | 65.0 (61.9 – 68.0) |

| Stepfamily | 717 | 14.7 (13.4 – 16.2) | 398 | 14.7 (13.0 – 16.5) | 319 | 14.8 (13.1 – 16.7) |

| Single parent | 1,010 | 18.7 (16.8 – 20.7) | 605 | 19.5 (17.3 – 21.9) | 405 | 17.8 (15.5 – 20.4) |

| Other | 162 | 2.6 (2.1 – 3.2) | 96 | 2.7 (2.1 – 3.6) | 66 | 2.4 (1.7 – 3.4) |

| Parent education | ||||||

| <HS diploma | 472 | 9.4 (7.7 – 11.5) | 284 | 10.0 (8.0 – 11.9) | 188 | 9.0 (6.8 – 11.8) |

| HS diploma/GED | 1,408 | 29.4 (26.4 – 32.7) | 812 | 29.9 (26.7 – 33.4) | 596 | 28.9 (25.5 – 32.6) |

| Some postsecondary | 1.021 | 21.4 (19.5 – 23.4) | 602 | 22.6 (20.3 – 25.1) | 419 | 20.2 (17.6 – 23.0) |

| ≥Bachelors | 2,160 | 39.7 (35.3 – 44.4) | 1,132 | 37.7 (32.9 – 42.8) | 1,028 | 42.0 (37.2 – 46.9) |

| High depressive symptomsa | ||||||

| Wave I | 547 | 10.0 (8.7 – 11.4) | 364 | 12.3 (10.5 – 14.3) | 183 | 7.5 (6.2 – 9.0) |

| Wave II | 587 | 10.1 (9.0 – 11.2) | 406 | 12.9 (11.5 – 14.5) | 181 | 7.0 (5.7 – 8.5) |

| Wave III | 462 | 9.1 (8.1 – 10.2) | 294 | 10.4 (9.0 – 12.0) | 168 | 7.8 (6.5 – 9.3) |

| Sexual initiation WI–WII | 814 | 15.4 (13.7 – 17.3) | 470 | 16.1 (14.0 – 18.3) | 344 | 14.7 (12.5 – 17.2) |

| Sexual debut timingb | ||||||

| Early | 918 | 20.1 (17.9 – 22.4) | 557 | 21.3 (18.8 – 24.0) | 361 | 18.7 (16.2 – 21.4) |

| Typical | 2,489 | 49.3 (47.5 – 51.2) | 1,403 | 49.5 (46.9 – 52.1) | 1,086 | 49.2 (46.5 – 51.8) |

| Late | 1,654 | 30.6 (28.4 – 33.0) | 870 | 29.2 (26.5 – 32.1) | 784 | 32.2 (29.5 – 35.0) |

High depressive symptomatology was based on scoring at or above the proportionately adjusted cutpoint on the modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (range 0–27). The cutpoints are 10 for males and 11 for females.

Sexual debut prior to age sixteen was classified as early, debut between ages 16 and 18 was classified as typical, and debut after age 18 (including those who did not debut by Wave III interview) was classified as late.

Baseline depressive symptoms and timing of sexual debut

To assess the necessity of controlling for baseline depressive symptomatology, we began by testing Hypothesis 1a, using chi-square analyses to examine the crude bivariate relationship between baseline depressive symptoms and the timing of subsequent sexual debut. Tests of the relationship between baseline and later depressive symptomatology (Hypothesis 1b) are embedded in analyses for hypotheses two and three. Consistent with our expectations, among female participants, high baseline depressive symptomotology was significantly more prevalent for early and typical initiators compared to late initiators (10.7% early, 11.4% typical, and 6.8% of late, χ2 =9.79, p<0.01). However, among male participants, baseline depressive symptoms were unrelated to timing of sexual debut (6.0% early, 7.2% typical, and 6.4% late, χ2 =1.07, p>0.20). To conduct analyses similarly by sex, indicators for pre-debut depressive symptomatology were maintained in subsequent multivariable analyses.

Sexual debut and short-term depressive symptom outcomes

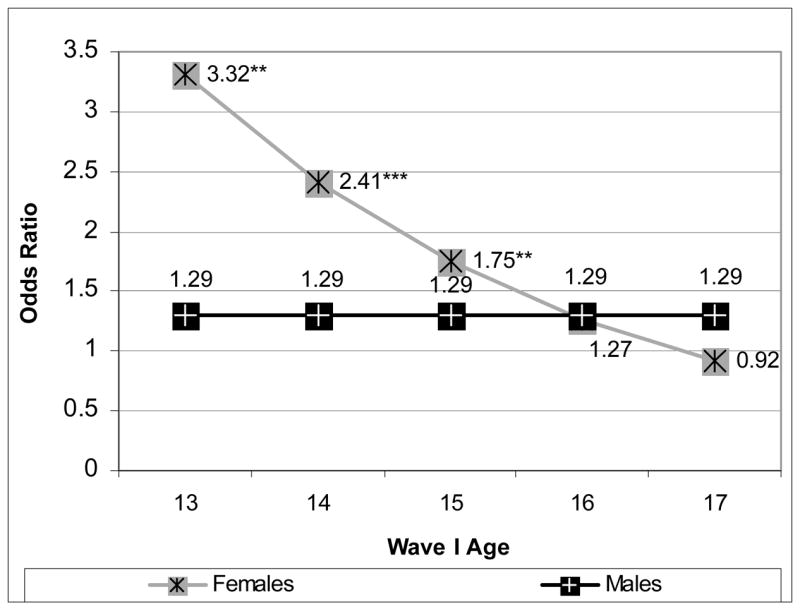

We next tested hypothesis 2 by assessing whether the relationship between sexual debut and subsequent depressive symptoms during adolescence varied by age and sex. Sexual debut between Waves I and II was significantly related to Wave II depressive symptom outcomes, but this association was moderated by sex and age (Figure 1). For female adolescents, after controlling for sociodemograhic characteristics and baseline depressive symptoms, the positive association between sexual debut and subsequent depressive symptomatology decreased with age; by age 16, sexual debut was no longer significantly associated with subsequent depressive symptoms. For male adolescents, sexual debut was not significantly associated with subsequent depressive symptoms at any age.

Figure 1. High Wave II depressive symptomatology: Persons who initiated sexual intercourse between Waves I and II versus those who did nota.

a Results from multivariable logistic regression models, run separately for female and male respondents, including the following covariates: Wave II sexual initiation status, Wave I age, Wave I high depressive symptoms, race, Hispanic ethnicity, Wave I living arrangement, and parent education. Female models also included a cross-product interaction between age and sexual initiation status. The interaction term was dropped from the male model because the interaction term was non-significant (p=0.229).

Sexual debut timing and emerging adult depressive symptom outcomes

Finally, we tested our third hypothesis by examining whether sexual debut timing was related to depressive symptomatology in emerging adulthood. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression results for female participants are presented in Table 2. In bivariate analyses, a number of sociodemograhic characteristics were positively associated with high depressive symptomatology in emerging adulthood. Black race, not living with both biologic parents in adolescence and low parent education (less than high school diploma) were positively associated with emerging adult depressive symptomatology. Further, high baseline pre-debut depressive symptomatology was strongly associated with depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood (OR=3.39, 95% CI 2.31 – 4.99). Although early sexual debut timing was significantly positively associated with emerging adult depressive symptoms at the bivariate level (OR=1.82, 95% CI 1.17 – 2.83), typical debut timing was not (OR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.78 – 1.71). In adjusted multivariable analyses, the only variable that remained significantly associated with emerging adult depressive symptoms was Wave I pre-debut depressive symptoms (OR=3.14, 95% CI 2.09 – 4.71); sexual debut timing was no longer significantly associated with Wave III depressive symptoms. To test the robustness of the findings to the dependent variable specification, we also ran OLS models using the continuous version of the depression score; results were equivalent (available from the authors on request).

Table 2.

Sexual debut timing and emerging adult depressive symptomatology: Logistic regression results, Female Participants

| Crude Bivariate Relationships: Emerging Adult Depressive Symptomsa |

Adjusted Logistic Regression: Emerging Adult Depressive Symptomsa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p-valuec | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-valuec | |

| Sexual debut timingb | ||||

| Late | Referent | 0.015 | Referent | 0.284 |

| Typical | 1.16 (0.78 – 1.71) | 0.93 (0.61 – 1.42) | ||

| Early | 1.82 (1.17 – 2.83) | 1.28 (0.78 – 2.12) | ||

| WIII Age | 0.92 (0.80 – 1.05) | 0.209 | 0.87 (0.76 – 1.00) | 0.055 |

| WI depressive symptoms | 3.39 (2.31 – 4.99) | <.001 | 3.14 (2.09 – 4.71) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Referent | 0.040 | Referent | 0.368 |

| Black | 1.62 (1.09 – 2.41) | 1.31 (0.83 – 2.07) | ||

| Other | 1.53 (0.99 – 2.36) | 1.29 (0.81 – 2.04) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.33 (0.84 – 2.09) | 0.224 | 1.07 (0.63 – 1.84) | 0.777 |

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Two biologic parents | Referent | <.001 | Referent | 0.056 |

| Stepfamily | 1.61 (1.05 – 2.47) | 1.44 (0.92 – 2.27) | ||

| Single parent | 2.05 (1.34 – 3.13) | 1.62 (0.97 – 2.71) | ||

| Other | 2.93 (1.49 – 5.76) | 2.43 (1.15 – 5.14) | ||

| Parent education | ||||

| HS diploma/GED | Referent | 0.032 | Referent | 0.591 |

| <HS diploma | 2.20 (1.31 – 3.71) | 1.48 (0.83 – 2.65) | ||

| Some college | 1.43 (0.92 – 2.23) | 1.15 (0.72 – 1.83) | ||

| ≥Bachelors | 1.39 (0.84 – 2.31) | 1.17 (0.70 – 1.95) | ||

High depressive symptomatology was based on scoring at or above the proportionately adjusted depression cutpoint on the modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (range 0–27). The cutpoints are 10 for males and 11 for females.

Sexual debut prior to age sixteen was classified as early, debut between ages 16 and 18 was classified as typical, debut after age 18 (including those who did not debut by Wave III interview) was classified as late.

For multi-category predictor variables, p-values refer to joint tests of statistical significance

Table 3 presents bivariate and multivariable logistic regression results for male participants. In bivariate analyses, the sociodemograhic characteristics other race and low parent education (less than high school diploma) were positively associated with male participants’ emerging adult depressive symptoms. Compared with female participants, pre-debut depressive symptoms were even more strongly associated with emerging adult depressive symptoms (OR=4.95, 95% CI 2.78 – 8.81). Sexual debut timing, however, was not significantly associated with male participants’ emerging adult depressive symptoms in bivariate analyses. In adjusted multivariable analyses, Wave I pre-debut depressive symptoms (OR = 4.33, 95% CI 2.32 – 8.10) and low parent education (less than high school diploma, OR = 2.79, 95% CI 1.39 – 5.59) remained significantly associated with emerging adult depressive symptoms; sexual debut timing remained unassociated with emerging adult depressive symptoms. To test the robustness of the findings to the dependent variable specification, we also ran OLS models using the continuous version of the depression score; results were equivalent (available from the authors on request).

Table 3.

Sexual debut timing and emerging adult depressive symptomatology: Logistic regression results, Male Participants

| Crude Bivariate Relationships: Emerging Adult Depressive Symptomsa |

Adjusted Logistic Regression: Emerging Adult Depressive Symptomsa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p-valuec | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-valuec | |

| Sexual debut timingb | ||||

| Late | Referent | 0.783 | Referent | 0.772 |

| Typical | 1.10 (0.65 – 1.86) | 1.06 (0.61 – 1.84) | ||

| Early | 1.25 (0.67 – 2.31) | 1.26 (0.65 – 2.43) | ||

| WIII Age | 1.14 (0.97 – 1.35) | 0.120 | 1.12 (0.95 – 1.32) | 0.174 |

| WI depressive symptoms | 4.95 (2.78 – 8.81) | <.001 | 4.33 (2.32 – 8.10) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Referent | 0.010 | Referent | 0.078 |

| Black | 1.54 (0.82 – 2.86) | 1.35 (0.72 – 2.54) | ||

| Other | 2.04 (1.22 – 3.38) | 1.72 (1.02 – 2.90) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.74 (0.88 – 3.42) | 0.108 | 0.90 (0.42 – 1.92) | |

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Two biologic parents | Referent | 0.134 | Referent | 0.494 |

| Stepfamily | 1.72 (1.03 – 2.89) | 1.57 (0.88 – 2.78) | ||

| Single parent | 1.47 (0.87 – 2.48) | 1.09 (0.63 – 1.89) | ||

| Other | 1.17 (0.35 – 3.94) | 0.99 (0.30 – 3.22) | ||

| Parent education | ||||

| HS diploma/GED | Referent | <.001 | Referent | 0.039 |

| <HS diploma | 3.73 (2.09 – 6.66) | 2.79 (1.39 – 5.59) | ||

| Some college | 1.36 (0.83 – 2.24) | 1.14 (0.70 – 1.85) | ||

| ≥Bachelors | 1.30 (0.73 – 2.31) | 1.27 (0.72 – 2.24) | ||

High depressive symptomatology was based on scoring at or above the proportionately adjusted depression cutpoint on the modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (range 0–27). The cutpoints are 10 for males and 11 for females.

Sexual debut prior to age sixteen was classified as early, debut between ages 16 and 18 was classified as typical, debut after age 18 (including those who did not debut by Wave III interview) was classified as late.

For multi-category predictor variables, p-values refer to joint tests of statistical significance

DISCUSSION

Although past research has found that adolescent sexual debut is positively associated with adolescent depressive symptoms among some adolescents, the implications of sexual debut timing for mental health beyond adolescence are unknown. The present study examined whether sexual debut timing is related to emerging adult depressive symptomatology, after controlling for adolescent sociodemographic characteristics and pre-existing depressive symptoms. There are three major findings.

First, both hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported. Similar to Longmore et al., we found baseline depressive symptoms were predictive of earlier sexual debut timing among female adolescents (Longmore et al., 2004). Further, significant, strong relationships between pre-debut and emerging adult depressive symptomatology were found, consistent with past studies documenting considerable continuity in depressive symptoms from adolescence to emerging adulthood (Aalto-Setala et al., 2002). Together, these findings highlight the importance of controlling for baseline depressive symptomatology when studying effects of adolescent sexual debut, due to possible issues of reverse-causality. These findings also underline the importance of detecting and treating depression early in adolescence, because such early onset of depression may place young persons at higher risk of depressive symptoms into later life. Development of more specific screening instruments for adolescent depression will be key to this effort, given past studies documenting the high burden placed on schools using currently available instruments (Hallfors et al., 2006).

Second, we also found support for our second hypothesis. Similar to the Meier study (Meier, 2007), short-term increases in depressive symptomatology after sexual debut were only observed for female adolescents with early age at debut (i.e., before age 16); Wave II depressive symptomatology was unassociated with sexual debut status for male adolescents of any age. These findings are not surprising, given past research documenting sex differences in associations between romantic relationship involvement and depressive symptoms (Joyner & Udry, 2000), as well as health risk behaviors and depressive symptoms (Waller et al., 2006). They are also consistent with sex differences suggested by the Stress – Vulnerability Model. Qualitative studies suggest that female adolescents are subject to more negative social sanctions after debut than male adolescents, including pejorative labeling by peers and problem-focused parental interactions (Shoveller, Johnson, Langille, & Mitchell, 2004; Tolman, 2002). Such negative environmental feedback has likewise been connected to post-debut depressive symptom changes (Ream, 2006). These findings suggest that the associations between patterns of risky behavior and depressive symptomatology found in other studies (Hallfors et al., 2005) could be driven largely by female adolescents who debut especially early.

Third, we found support for hypothesis 3, our main study hypothesis. Sexual debut timing was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. For male participants, sexual debut timing was not associated with emerging adult depressive symptoms in either crude or adjusted analyses. For female participants, the association between debut timing and depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood was explained by pre-debut differences in depressive symptoms. Such findings suggest the associations between adolescent sexual debut (or patterns of sexual and substance use risk taking) and adolescent females’ depressive symptoms observed in this and other studies (Hallfors et al., 2005; Meier, 2007) may typically be short-lived, and that disruptions in functioning due to early stage termination or other potential causal mediators can be overcome. This pattern of findings is consistent with a transactional model, and points to the importance of investigating the quality of the sexual transition experience itself, aspects of the adolescent’s biopsychosocial characteristics that may heighten their vulnerability to depression, physical and cultural context, and subsequent experiences that might moderate the associations between debut timing, sexual activity, and health.

The current study has the strengths of a large, nationally-representative sample, as well as a prospective design. However, its limitations must also be noted. First, measurement of depressive symptoms was based on an abbreviated subset of CES-D items. Although preliminary analyses indicated there was considerable agreement between the abbreviated and longer scales for the dichotomous high depressive symptom indicator, the problem of measurement error is still present. If such measurement error is nondifferential across the sexual debut timing groups, odds ratio estimates for sexual debut timing may be biased toward the null. Future studies should attempt to replicate the present findings using the full CES-D or another validated instrument.

A second limitation is that the analysis of emerging adult depressive symptoms relied on respondents’ retrospective report of age at first sex, which may be inconsistent with adolescent-reported debut age and subject to recall or reporting biases, although evidence is mixed on this point (Capaldi, 1996; C. J. T. Halpern, Udry, Suchindran, & Campbell, 2000; Upchurch, Lillard, Aneshensel, & Fang Li, 2002). However, such inconsistencies have little effect on determining covariates of age at debut (Upchurch et al., 2002), and self-reported honesty in answering sexual behavior questions has been found to increase with age (Siegel, Aten, & Roghmann, 1998). Given extensive missing data on dates of sexual debut in Waves I and II, the need for classifying debut timing for respondents who initiated sexual intercourse after the last adolescent interview (Wave II), and the likely greater honesty at higher ages, using the Wave III retrospective report was deemed the most valid approach. Supplemental analyses conducted by the authors also supported no substantive difference in findings when changing assumptions regarding the validity of debut report at different waves.

Third, the present study only examined relationships between the timing of first vaginal sexual intercourse and emerging adult depressive symptoms. Given findings supporting differential short-term effects of various sexual activities during adolescence (Brady & Halpern-Felsher, 2007), the present findings may only be relevant to vaginal sexual intercourse initiation. Also, relationships between the timing of vaginal sexual intercourse initiation and depressive symptom changes may differ by sexual identity. That is, coital debut may have lower salience for sexual minority youth, and therefore be even less related to mental health outcomes. Future research should explore these possible subgroup differences.

Results from the present study suggest that adolescent sexual debut, although possibly related to short-term increases in depressive symptomatology for young female adolescents, is not necessarily related to longer-term depressive symptom outcomes. Although further research using validated measures of mental health is warranted, these findings suggest interventions aimed at delaying females’ sexual intercourse until at least age 16 may help prevent some adolescent depressive episodes, although they may not have an impact on later life depressive symptoms. On the other hand, the depressive symptoms experienced by some adolescents shortly after sexual initiation are not necessarily without consequence. It is possible that these episodes have lasting effects for vulnerable individuals or contribute to other emerging adult outcomes. Other studies examining whether early sexual debut has lasting negative consequences into emerging adulthood demonstrate mixed findings. For example, early sexual debut has been negatively associated with educational progress (Spriggs & Halpern, 2008) and positively associated with delinquency (Armour & Haynie, 2007) in emerging adulthood. However. a study by Kaestle et al. (2005) found that the association between early sexual debut and STD infection diminished with age (Kaestle, Halpern, Miller, & Ford, 2005). Further, a study conducted by Harden et al. found that the association between sexual debut timing and emerging adult delinquency supported in the Armour and Haynie study was no longer significant after unobserved genetic and family environmental factors were controlled in matched sibling analyses (Harden, Mendle, Hill, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2008). Together, findings indicate that the effects of early sexual debut on long-term outcomes vary by the outcome studied, the psychosocial characteristics and developmental history of the individual, and presumably by the context and characteristics of the debut experience as well. Future research should attempt to better contextualize sexual transitions to understand developmental implications more fully.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (addhealth@unc.edu). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. Ms. Spriggs’ time on this project was supported by the Carolina Population Center, NICHD NRSA predoctoral traineeship, grant number NIH-NICHD T32-HD07168. An earlier version of this manuscript was presented at the 2007 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C.

References

- Aalto-Setala T, Marttunen M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Poikolainen K, Lonnqvist J. Depressive symptoms in adolescence as predictors of early adulthood depressive disorders and maladjustment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(7):1235–1237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abma J, Martinez G, Mosher W, Dawson B. Trends in HIV-related risk behaviors among high school students--United States, 1991–2005. Vital Health Statistics. 2004;24:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Armour S, Haynie DL. Adolescent sexual debut and later delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(2):141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, Turner RJ. Family structure and mental health: the mediating effects of socioeconomic status, family process, and social stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(2):156–169. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billy JO, Landale NS, Grady WR, Zimmerle DM. Effects of sexual activity on adolescent social and psychological development. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1988;51(3):190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents’ reported consequences of having oral sex versus vaginal sex. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):229–236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Graber JA. Puberty as a biological and social event: Implications for research on pharmacology. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15(8):663–671. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge V, Felts M, Chenier T, Parrillo AV. Drug use, sexual activity, and suicidal behavior in US high school students. Journal of School Health. 1995;65(6):222–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1995.tb03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. The reliability of retrospective report for timing first sexual intercourse for adolescent males. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1996;11(3):375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Capron C, Therond C, Duyme M. Brief report: Effect of menarcheal status and family structure on depressive symptoms and emotional/behavioural problems in young adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(1):175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55(1–108) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis WJ, Cicchetti D. Moving research on resilience into the 21st century: Theoretical and methodological considerations in examining the biological contributors to resilience. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:773–810. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski J, Frank E, Young E, Shear K. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden AL. Abstinence and abstinence-only education. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(2):151–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J. Transitions and turning points: Navigating the passage from childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(4):768–776. [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Galen BR. Bewtixt and between: Sexuality in the context of adolescent transitions. In: Jessor R, editor. New Perspectives on Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 270–318. [Google Scholar]

- Guggino JM, Ponzetti JJ., Jr Gender differences in affective reactions to first coitus. Journal of Adolescence. 1997;20(2):189–200. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Brodish PH, Khatapoush S, Sanchez V, Cho H, Steckler A. Feasibility of screening adolescents for suicide risk in “real-world” high school settings. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(2):282–287. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence - sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: association with sex and drug behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CJT, Udry JR, Suchindran C, Campbell B. Adolescent males’ willingness to report masturbation. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37(4):327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Waller MW, Spriggs A, Hallfors DD. Adolescent predictors of emerging adult sexual patterns. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(6):e1–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson L. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Mendle J, Hill JE, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Rethinking timing of first sex and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(4):373–385. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2003 Retrieved July 16, 2007, from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.html.

- Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review. 2008;115(2):291–313. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Udry JR. You don’t bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(4):369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, Ford CA. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(8):774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Soloman A, Seeley JR, Zeiss A. Clinical implications of “subthreshold” depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, Manning WD, Giordano PC, Rudolph JL. Self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and adolescents’ sexual onset. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67(3):279–295. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Almazan EP. Connections between childhood and adulthood. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. Hingham, MA: Klewer Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meier AM. Adolescent first sex and subsequent mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112(6):1811–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC. Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(1):22–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher WD, McNally JW. Contraceptive use at first premarital intercourse: United States, 1965–1988. Family Planning Perspectives. 1991;23(3):108–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell BL, O’Donnell CR, Stueve A. Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex-related risks among urban minority youth: the reach for health study. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33(6):268–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Taylor B. The biological approach to adolescence: Biological change and psychological adaptation. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1980. pp. 117–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL. Reciprocal effects between the perceived environment and heterosexual intercourse among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(5):771–785. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Screening for adolescent depression: a comparison of depression scales. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(1):58–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Lowry R, Brener ND, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(10):1582–1588. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Morrow B, Anderson JE, Lindberg LD. Contraceptive use and pregnancy risk among U.S. high school students, 1991–2003. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(2):106–111. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.106.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen B. Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: Race and gender differences. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2004;7(3):133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoveller JA, Johnson JL, Langille DB, Mitchell T. Socio-cultural influences on young people’s sexual development. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(3):473–487. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DM, Aten MJ, Roghmann KJ. Self-reported honesty among middle and high school students responding to a sexual behavior questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. Generation gaps in attitudes and values from the 1970s to the 1990s. In: Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 177–221. [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs A, Halpern CT. Sexual debut timing and postsecondary education initiation in early adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2008 doi: 10.1363/4015208. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC, Haslimeier C, Metzke CW. The outcome of episodic versus persistent adolescent depression in young adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;96(1–2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL. Dilemmas of desire : teenage girls talk about sexuality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Levy-Storms L, Sucoff CA, Aneshensel CS. Gender and ethnic differences in the timing of first sexual intercourse. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(3):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Lillard LA, Aneshensel CS, Fang Li N. Inconsistencies in reporting the occurence and timing of first intercourse among adolescents. J Sex Res. 2002;39(3):197–206. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Mason WM, Kusunoki Y, Johnson M, Kriechbaum J. Social and behavioral determinants of self-reported STD among adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(6):276–287. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.276.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller MW, Hallfors DD, Halpern CT, Iritani BJ, Ford CA, Guo G. Gender differences in associations between depressive symptoms and patterns of substance use and risky sexual behavior among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(3):139–150. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]