Abstract

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA4) delivers inhibitory signals to activated T cells. CTLA4 is constitutively expressed on regulatory CD4+ T cells (Tregs), but its role in these cells remains unclear. CTLA4 blockade has been shown to induce antitumor immunity. In this study, we examined the effects of anti-CTLA4 antibody on the endogenous CD4+ T cells in cancer patients. We show that CTLA4 blockade induces an increase not only in the number of activated effector CD4+ T cells, but also in the number of CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs. Although the effects were dose-dependent, CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells could be expanded at lower antibody doses. In contrast, expansion of effector T cells was seen only at the highest dose level studied. Moreover, these expanded CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are induced to proliferate with treatment and possess suppressor function. Our results demonstrate that treatment with anti-CTLA4 antibody does not deplete human CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs in vivo, but rather may mediate its effects through the activation of effector T cells. Our results also suggest that CTLA4 may inhibit Treg proliferation similar to its role on effector T cells. This study is registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00064129, registry number NCT00064129.

Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy relies on the induction of effector T cells to mediate tumor regression. Activation of these T cells requires recognition of specific antigens in concert with costimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 expressed on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). These costimulatory molecules interact with CD28, which is constitutively expressed on T cells and delivers signals required by naive T cells to become activated and proliferate.1 Once activated, these T cells transiently up-regulate cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA4) on their cell surface, which interacts with the same costimulatory molecules but now serves to inhibit cell cycle progression and IL-2 production.2,3 Thus, CTLA4 signaling provides negative feedback to activated T cells, thereby dampening an immune response. Blocking CTLA4 with anti-CTLA4 antibodies enhances effector T-cell responses and can induce T cell–mediated rejection of certain tumors in mouse models.4 With fewer immunogenic tumors such as the mouse B16 melanoma, however, CTLA4 blockade is effective only if combined with the injection of irradiated granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)–transduced tumor cells (GVAX).5–7 Human anti-CTLA4 antibodies have entered clinical trials and have demonstrated antitumor responses in patients, predominantly in melanoma and kidney cancer patients.8–11 These treatments have been associated with immune-mediated side effects, manifesting as inflammation within skin, colon, eye, and pituitary gland.12,13

Although the treatment effects have been shown to be T-cell dependent, the mechanism by which anti-CTLA4 antibodies induce tumor regression, as well as these immune-mediated side effects, remains unclear. CTLA4 blockade may directly enhance the proliferation and/or function of effector CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells. Alternatively, CTLA4 blockade could negatively impact CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), which can suppress immune responses to both self and nonself and are therefore crucial in the maintenance of immunologic tolerance.14,15 Studies in humans have demonstrated that patients with cancer may have an increased number of Tregs in their blood or even within the tumor microenvironment.16–20 Moreover, the presence of Tregs within the tumor has been associated with worse clinical outcome.17,21

Tregs constitutively express the nuclear transcription factor forkhead box protein P3 (FoxP3) and also constitutively express CTLA4 on their cell surface.22,23 Thus, anti-CTLA4 antibodies could enhance antitumor immunity through the depletion of these cells. In fact, depletion of Tregs by targeting CD25, which may also be constitutively expressed on the surface of Tregs,24 enhances effective antitumor immunity in both animal models and humans.25–27 A recent study in humans treated with anti-CTLA4 antibody reported a transient reduction after treatment in the number of CD4+CD25+CD62L+ cells, which could represent a depletion of Tregs.28 Anti-CTLA4 antibody may also impair the suppressive function of Tregs,29,30 although a study in humans failed to demonstrate any in vitro effects of anti-CTLA4 antibody on Treg-mediated suppression.31 Finally, a more recent study in mice demonstrated that the combination of CTLA4 blockade with GVAX increased the number of both Tregs and effector T cells in the tumor, with skewing of the ratio toward effector T cells correlating with tumor rejection.32

Here we show that anti-CTLA4 antibody-based immunotherapy induces an increase not only in activated effector CD4+ T cells, but also in functional Tregs in cancer patients. Consistent with this finding, we saw enhanced proliferation of Tregs in vivo after treatment. Importantly, the number of Tregs was increased at lower doses of anti-CTLA4 antibody, although the increase in the number of activated effector T cells was primarily seen at higher doses, suggesting a higher sensitivity of Tregs to CTLA4 blockade. Our data, therefore, demonstrate that CTLA4 blockade acts not by the depletion of Tregs. Rather, our data strongly support the notion that CTLA4 blockade induces clinical responses through the induction of effector T cells.

Methods

Study subjects

Study participants were at least 18 years old with histologically confirmed metastatic prostate cancer with disease evident on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or bone scans. Study subjects were required to have progressive cancer by the Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Working Group Consensus Criteria33 with rising PSA levels and/or worsening scans at study entry. Subjects must not have received prior chemotherapy or immunotherapy. They could not have received radiation therapy within 4 weeks of participation on the study. Participants also could not have a history of autoimmune disease, nor could they be taking systemic corticosteroids during the study. The study was performed with University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board approved protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical trial

We carried out a phase 1 study with escalating doses of anti-CTLA4 antibody in combination with a fixed dose of GM-CSF to show the safety and feasibility of this treatment in prostate cancer patients. Initially, cohorts of 3 subjects were sequentially enrolled into each of 5 dose cohorts at escalating dose levels of anti-CTLA4 antibody. If a single subject experienced significant treatment-related side effects potentially related to anti-CTLA4 antibody at a given dose, the cohorts were expanded to 6 subjects. Subjects received up to 4 doses of anti-CTLA4 antibodies at the specified doses. These doses were given in 4-week cycles with GM-CSF administered daily on the first 14 days of these cycles. GM-CSF treatment could continue until disease progression or toxicity. A total of 24 patients were accrued to this phase 1 study. Eighteen had bone metastasis, 8 had lymph node metastasis, and 3 had metastasis to visceral organs. The median age was 70 years with a range of 60 to 82 years. At baseline, the median PSA was 35.3 ng/mL (normal range, 0-4 ng/mL), with a range of 6.72 to 435.1. Peripheral blood was obtained from the participants at baseline before the initiation of treatment and every 4 weeks while on study for immune monitoring.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from patients before treatment and monthly while on treatment. PBMCs were either stained fresh and assessed by flow cytometry or cryopreserved for later study. The fluorochrome-labeled antihuman antibodies to CD3, CD4, CD25, CD127, HLA-DR, CTLA4, CD69, CD71, KI67, IL-10, IL-2, and IFN-γ were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Alexa488-conjugated antihuman FoxP3 was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Intracellular staining was performed according to the BioLegend protocol. Stained cells were washed and analyzed with a FACSCalibur or LSR II (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. All data analysis was performed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). CD4 T-cell counts were calculated by multiplying the percentage of the indicated CD4 T-cell phenotype gated on lymphocytes by the absolute lymphocyte counts measured simultaneously in a complete blood count.

Surface CTLA4 capture staining

Patient PBMCs were cultured for 6 hours at 37°C/5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 plus 5% human serum (Cambrex, North Brunswick, NJ) containing 2 μM monensin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Epicentre, Madison, WI), and an anti-CTLA4 PE antibody (BD Biosciences) or an isotype matched control antibody. PBMCs were then washed and stained for surface markers including IgG PE or CTLA4 PE where indicated at 4°C for 30 minutes. PBMCs were then washed, fixed, and stained intracellularly according to the BioLegend protocol where indicated. Labeled PBMCs were then washed and analyzed on a flow cytometer.

Cytokine production assay

Cryopreserved patient PBMCs were thawed and then washed and cultured in RPMI-1640 plus 5% human serum (Cambrex). Baseline and posttreatment time points were assessed in parallel. The PBMCs were cultured with or without 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 (clone OKT3) and 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD28 (clone 9.3) antibodies for 8 hours in an incubator at 37°C 5% CO2. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were also cultured with brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10 μg/mL. The cells were then washed and stained for surface markers as well as for intracellular FoxP3, IFN-γ, IL-2, and/or IL-10.

Isolation of Tregs

PBMCs from subjects after 2 cycles of treatment were isolated fresh from 50 mL of blood by Ficoll density centrifugation. After washing, the PBMCs were counted, resuspended in sorting buffer (PBS + 0.1% HSA + 0.5 mM EDTA), and stained with fluorescently labeled antihuman CD4, anti-CD127, and anti-CD25 antibodies for 30 minutes at 4°C. The stained cells were then washed, resuspended in sorting buffer at 2 × 107/mL, and sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). CD4+ T cells were gated based on the expression of CD127 and CD25. CD4+CD127loCD25hi cells were used as Tregs. CD4+CD127hiCD25lo T cells were used as responding effector T cells.

T-cell suppression assay

Suppression assays were performed as previously published.34 Briefly, 30 000 sorted CD4+CD127hiCD25− cells (responders) were cocultured with 100 000 irradiated allogeneic PBMCs and 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (clone OKT3) in triplicate wells of 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates. A titration of CD25+CD127−CD4+ Tregs was added in the indicated ratios. Cells were incubated for 5 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. 3H-thymidine was added to each well for the final 18 hours of culture. The assays were harvested with a Tomtec cell harvester and counted with a Perkin Elmer MicroBeta Trilux scintillation counter (Waltham, MA). Proliferation was reported as a stimulation index (SI: = CPM/CPM of responders alone).

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome for this phase 1 study was to determine the safety of anti-CTLA4 given with GM-CSF. The standard dose escalation procedure for phase 1 trials was carried out with 3 to 6 subjects accrued per dose cohort. The maximum tolerated dose level was defined as the dose of anti-CTLA4 resulting in 0 of 3 subjects or only 1 of 6 subjects for an expanded dose cohort experiencing dose-limiting toxicity. A total of 24 subjects were accrued to 5 different dose levels (Figure 1). Due to the small sample size, the nonparametric Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used to evaluate the change in FoxP3+ CD4+ T-cell count from baseline to week 16. Outcomes for immunologic and clinical outcomes were summarized with descriptive statistics and graphically.

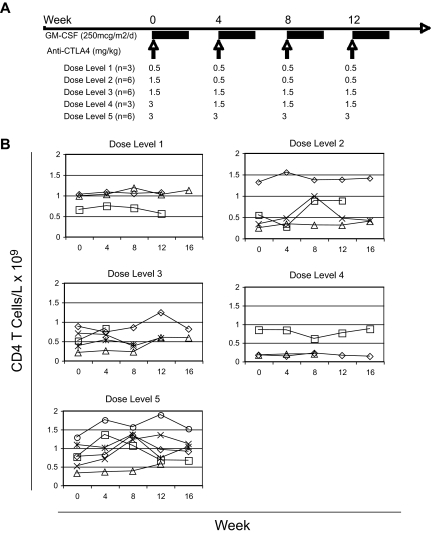

Figure 1.

Administration of anti-CTLA4 antibody and GM-CSF. (A) The dose of anti-CTLA4 antibody (mg/kg) and number of patients (n) on each dose level are presented. (B) The counts of CD4+ T cells per volume of blood were calculated by multiplying the percentage of CD4+ T cells by the absolute lymphocyte counts measured simultaneously. Each row represents the corresponding dose level. Each line represents the counts for each evaluable subject within the specified dose level.

Results

Clinical trial

Patients with progressive metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) were candidates for a phase 1 dose escalation study with sequential cohorts receiving increasing dose levels of anti-CTLA4 antibody. Consenting study participants were enrolled into dose cohorts and received 4 doses of fully human anti-CTLA4 IgG1 antibody (ipilimumab; Medarex, Princeton, NJ) every 28 days (Figure 1A). Subjects also received daily doses of GM-CSF 250 μg/m2 (sagramostim; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Seattle, WA) subcutaneously daily on days 1 to 14 of each 28-day cycle until disease progression or development of a treatment-related adverse event. Twenty-four study subjects were enrolled on this clinical trial.

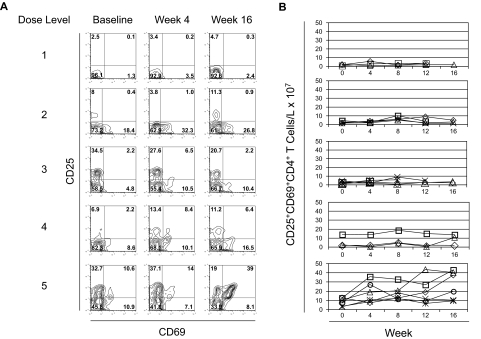

Expansion of activated CD4+ T cells with anti-CTLA4 antibody treatment

Subjects entering the study had variable CD4 T-cell counts at baseline, and there was no consistent change in the total CD4+ T-cell counts during treatment across the different dose levels (Figure 1B). We then assessed the activation of circulating CD4+ T cells by staining for activation markers CD25 and CD69 (Figure 2A). With dose levels 1 to 4, only subtle, if any, increases were seen in the number of circulating of activated CD25+CD69+CD4+ T cells per blood volume after treatment (Figure 2B). Moreover, any increases in CD25+CD69+CD4+ T cells were transient in these lower dose levels. By dose level 5, however, the number of activated CD25+CD69+CD4+ T cells per volume of blood increased after treatment, and persisted throughout the treatment (Figure 2B). In fact, all of the subjects at this dose level had greater than twice the number of circulating CD25+CD69+CD4+ T cells at week 16 compared with their number at baseline. These results demonstrate a threshold anti-CTLA4 antibody dose for CD4+ T-cell activation. Although CD4+ T cells were either not activated or only transiently activated at the lower dose levels of anti-CTLA4 antibody, persistent CD4+ T-cell activation required repetitive dosing of anti-CTLA4 antibody at the threshold of 3 mg/kg (dose level 5).

Figure 2.

Activation of CD4+ T cells with escalating doses of anti-CTLA4 antibody. (A) PBMCs at baseline, week 4, and week 16 of treatment from study subjects in each dose level were stained with antibodies to CD4, CD25, and CD69. Stained cells were then assessed by flow cytometry and gated on CD4+ T cells. Each row represents a different dose level. Numbers on plots represent the percentage of cells for each quadrant. Individual study subjects are presented from each dose level. Gating for CD25 and CD69 expression was set with results from staining with isotype-matched control IgG. (B) The counts of CD25+CD69+ CD4+ T cells per volume of blood was calculated by multiplying the percentage of CD25+CD69+CD4+ T cells by the absolute lymphocyte counts measured simultaneously. Each row represents the corresponding dose level. Each line represents the counts for each evaluable subject within the specified dose level.

Expansion of CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs with anti-CTLA4 antibody treatment

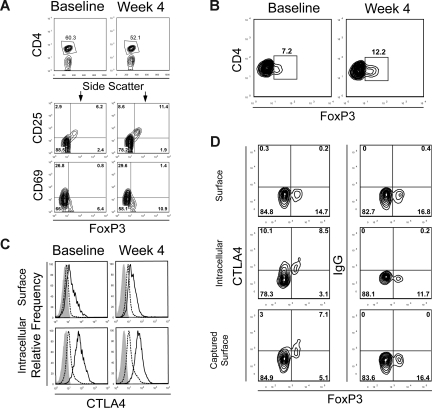

Because of the increase in CD4+CD25+ T cells, we examined whether these expanded cells were Tregs because Tregs can also express CD25. To identify Tregs, we performed intracellular staining for FoxP3, a transcription factor that is required for Treg function (Figure 3A). Consistent with prior reports, FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells expressed elevated levels of CD25 (Figure 3A middle row). Moreover, we saw a significant increase in the percentage of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells after treatment with anti-CTLA4 antibody at 3 mg/kg that also expressed high levels of CD25 (Figure 3A right panels). We also found that FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells both before and after treatment did not express CD69 (Figure 3A bottom row). Thus, the CD25+CD69+CD4+ T cells expanded with treatment are distinct from FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells and are consistent with activated FoxP3− effector cells. Because subjects in this study were treated with both GM-CSF and anti-CTLA4 antibody, we assessed PBMCs from subjects participating in another trial investigating a single dose of anti-CTLA4 antibody alone at a dose of 3 mg/kg.35 Subjects in this clinical trial also had metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer and had not received prior chemotherapy. A similar magnitude of Treg expansion was seen 4 weeks after treatment in all 3 subjects assessed, demonstrating that anti-CTLA4 treatment alone is sufficient for this effect (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Expansion of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells after treatment. (A) PBMCs from baseline and at week 4 from a subject in dose level 5 were stained for CD4, CD25, and CD69 with fluorescence-labeled antibodies. Anti-FoxP3 antibody staining was performed after cell permeabilization. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry and gated on CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were gated (top panels) and analyzed for CD25, CD69, and FoxP3 expression. The numbers on plots represent the percentage of cells in each of the quadrants. Data are derived from 1 subject treated in dose level 5 and are representative of 6 subjects in this cohort. Gating for CD4+ FoxP3+ staining was set with results from isotype-matched control IgG staining. (B) PBMCs from baseline and at week 4 from a subject who received anti-CTLA4 antibody at 3 mg/kg alone in a separate clinical trial for metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer were also stained for CD4 and intracellular FoxP3. Results are representative of 3 patients assessed. (C) PBMCs from baseline and at week 4 from a subject in dose level 5 were stained for CD4 and FoxP3 as described. Phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CTLA4 antibody, which is not blocked by the study drug, was also added either before (surface staining, top panels) or after (intracellular staining, bottom panels) cell permeabilization. FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (solid line) or FoxP3− CD4+ effector T cells (dashed line) were gated and assessed for CTLA4 expression. Staining with an isotype-matched control antibody is also shown (shaded histogram). (D) Dynamics of the intracellular pool of CTLA4 were assessed by surface capture staining. PBMCs from a representative subject in cohort 5 at week 4 of treatment were cultured for 6 hours and stained with antibody for surface CTLA4 or intracellular CTLA4 (after permeabilization) at the conclusion of culture, or the cells were cultured in a cocktail containing monensin, brefeldin A, and an anti-CTLA4 antibody to capture surface CTLA4 that translocates to the cell membrane over this time. PBMCs were also stained for CD4 and FoxP3 with fluorescently labeled antibodies, assessed by flow cytometry, and gated on CD4+ T cells. Results are representative of PBMCs from 3 different patients in cohort 5 at week 4 or at baseline.

We also examined CTLA4 expression levels by CD4+ T cells by staining with an alternate anti-CTLA4 antibody that is not blocked by the study drug. We found that FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells express modest levels of surface CTLA4 but possess significantly higher levels of intracellular CTLA4 compared with FoxP3− CD4+ T cells (Figure 3C). This higher level of CTLA4 expression could render FoxP3+ CD4+ Tregs more susceptible to effects of CTLA4 blockade. We also found that FoxP3+ T cells maintain their levels of both cell surface and intracellular CTLA4 after treatment. The CTLA4 blockade, therefore, appears to act neither by depleting these FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells nor by affecting their intracellular stores of CTLA4. Because the bulk of the CTLA4 resides intracellularly within these T cells, we wished to determine the capacity of intracellular CTLA4 to be accessible on the cell surface over time by staining the cells over 6 hours while inhibiting internalization of surface proteins.36 Using a surface capture antibody labeling technique where anti-CTLA4 antibody was coincubated with the cells during the 6 hours of incubation at 37°C, CTLA4 can be detected on the surface of both FoxP3+ and FoxP3− CD4+ T cells (Figure 3D). Moreover, the levels of CTLA4 detected on the surface of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells during this 6-hour incubation were nearly identical to the levels of intracellular CTLA4 detected on FOXP3 cells. These results indicate that the majority of internal CTLA4 can translocate to the cell surface over this time. FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with high intracellular levels of CTLA4 would therefore be susceptible to CTLA4 blockade.

Given these results, we assessed cryopreserved PBMCs from study subjects across the different dose levels for FoxP3 expression where samples were available. Interestingly, a dose-effect relationship became apparent with FoxP3+ CD4+ T-cell expansion (Figure 4A). However, FoxP3+ CD4+ T-cell expansion was seen at dose levels 2 to 5 (Figure 4B). The change in the number of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells between baseline and week 16 was statistically significant (Figure 4C; P < .001, nonparametric Wilcoxon matched pairs test).

Figure 4.

Expansion of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells across dose levels of anti-CTLA4 antibody. (A) PBMCs from baseline, week 4, and week 16 were stained for CD4 and intracellular FoxP3. Stained cells were then assessed by flow cytometry and gated on CD4+ T cells. Each row represents results from individual patients corresponding to subjects presented in Figure 2A at different dose levels assessed longitudinally at each of the time points. Numbers on plots represent the percentage of cells for each quadrant. (B) The counts of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells per volume of blood was calculated by multiplying the percentage of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells by the absolute lymphocyte counts measured simultaneously in a complete blood count. Each row represents the corresponding dose level. Each line represents the counts for each evaluable subject within the specified dose level. (C) The change in the number of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells per volume of blood is compared by plotting the baseline count (x-axis) versus the week-16 measurement (y-axis). The solid line indicates no change in cell count between the 2 time points. There was a significant increase in cell count among patients treated on dose levels 2 to 5, with different symbols indicating the different dose cohorts (Wilcoxon matched pairs test: P = .001). All data points residing above the line indicate an increase in the number of cells.

Expanded FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells function as immunosuppressive Tregs

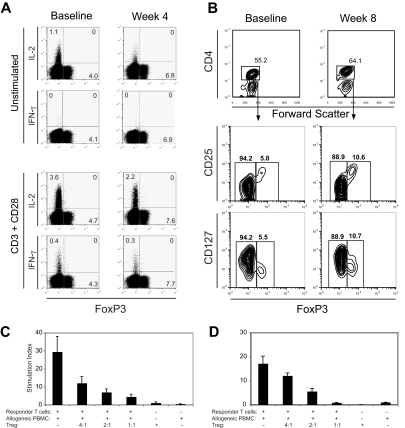

Whereas FoxP3 expression is generally felt to be restricted to Tregs in the mouse, in humans FoxP3 can be transiently induced in effector CD4+ T cells after activation.37 These activated effectors produce effector cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-2 in contrast to Tregs, which do not produce these cytokines. Therefore, we assessed the capacity of expanded FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells to produce these effector cytokines (Figure 5A). In CD4+ T cells obtained at baseline or at week 4 of treatment from these study subjects, IL-2 production could be seen in some FoxP3− CD4+ effector T cells, but not in the expanded FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells. After in vitro restimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, again only the FoxP3− CD4+ effector T cells could produce IFN-γ and IL-2, whereas the FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells did not. These results support the notion that the FoxP3+ T cells expanded by treatment do not simply represent effector T cells activated in vivo by CTLA4 blockade. Finally, these FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells expanded after treatment do not produce IL-10 (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Function of expanded Tregs. (A) CD4+ T cells were assessed for cytokine production before and after treatment by intracellular staining with fluorescence-labeled antibodies. PBMCs from before and after treatment were cultured with or without anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies for 8 hours. The cells were stained with anti-CD4 followed by intracellular staining for FoxP3, IFN-γ, and IL-2. For analysis, the PBMCs were gated on CD4+ T cells. Numbers on plots represent the percentages for each quadrant. Data shown are derived from 1 subject and are representative experiments from 3 different subjects. (B) PBMCs from baseline and at week 8 were stained for CD4, CD25, and CD127 followed by intracellular staining for FoxP3. Gating for FoxP3+ CD4+ cells was set with results from isotype-matched control IgG staining. Tregs were sorted from PBMCs derived from a study subject (C) in dose level 5 at week 8 and from a healthy control individual (D) based on the expression of CD4, CD127, and CD25. Thirty thousand autologous CD4+CD127+CD25− T cells (responders) were cocultured with 100 000 irradiated allogeneic PBMCs and anti-CD3 antibody. Where indicated, CD4+CD127−CD25+ Tregs were added at the indicated ratios of responders/Tregs. 3H-thymidine incorporation was assessed after 5 days of culture. Results are representative experiments from 3 different subjects. Error bars represent SD.

FoxP3 expression has also been shown to down-regulate CD127 expression on human CD4+ T cells.38 Human Tregs can, therefore, also be identified and isolated by their low levels of CD127 expression on CD25hiCD4+ T cells. We found that the FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells expanded by treatment possessed the same CD4+CD127loCD25hi phenotype (Figure 5B). We, therefore, used these markers to isolate Tregs by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from subjects after week 8 of treatment. When these posttreatment CD4+CD127loCD25hi T cells were sorted and used in a suppression assay, they potently inhibited proliferation of autologous PBMCs stimulated with irradiated, allogeneic PBMCs and anti-CD3 antibody in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5C).

Treatment induces proliferation of both FoxP3+ CD4+ and effector T cells

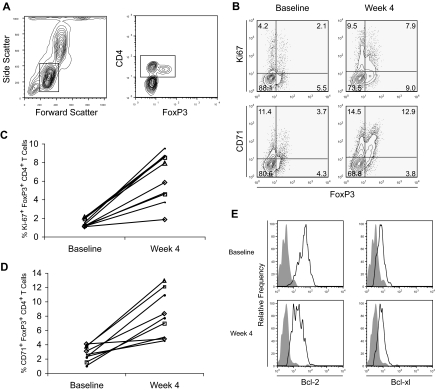

With the increase in the proportion of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells and activated T cells, we examined whether our treatment induces these T cells into cell cycle. To this end, we determined whether FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells were proliferating in vivo by staining for Ki67 and CD71. The former is a nuclear protein expressed exclusively in proliferating cells from G1 to M phase and has been used routinely to detect cell proliferation by flow cytometry.39,40 The latter, the transferrin receptor, is an activation marker for T cells that has been shown to correlate with T-cell proliferation.41,42 At baseline, before treatment, Ki67+ CD4+ T cells were evident in both FoxP3+ and FoxP3− CD4+ T cells. After treatment, the percentage of FoxP3+ and FoxP3− cells expressing Ki67 and CD71 was increased (Figure 6A,B). Moreover, the percentage of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells that express Ki67 after treatment for this subject represented 47% of the FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells, whereas the percentage of Ki67 expressing FoxP3− CD4+ T cells represented 11% of the FoxP3− CD4+ T cells (Figure 6B). Whereas none of the assessed patients in dose level 1 had an increase in the percentage of Ki67+ FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells or in the percentage of Ki67+ FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with treatment (data not shown), 8 of the 9 assessable patients across the higher dose cohorts had at least a doubling in these percentages (Figure 6C,D). Finally, we did not see an increase in the intracellular levels of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xl in FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells after treatment (Figure 6E), suggesting that the increase in the percentage of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells is not a result of prolonged survival.43 In fact, the levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl are actually decreased after treatment, consistent with these T cells being activated.

Figure 6.

Proliferation of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells with treatment. (A) PBMCs from a representative study subject in dose level 2 obtained before and after treatment were stained with CD4 and intracellular FoxP3 as well as for (B) CD71 and intracellular Ki67 expression with fluorescently labeled antibodies. Stained cells were assessed by flow cytometry and gated on CD4+ T cells for FoxP3, Ki67, and CD71 expression. Numbers on plots represent the percentages for each quadrant. The percentage of CD4 T cells that are (C) FoxP3+Ki67+ or (D) FoxP3+ CD71+ are shown at baseline and week 4 for the 9 patients assessed in dose levels 2 (▵), 3 (□), 4 (◇), and 5 (•). (E) PBMCs from before (top panels) and after (bottom panels) treatment were also stained with CD4 as well as stained intracellularly for FoxP3, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xl expression with fluorescently labeled antibodies. Stained cells were again assessed by flow cytometry and gated on FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells. Staining with anti-Bcl2 and anti–Bcl-xl antibodies (open histograms) and an isotype-matched control IgG (filled histogram) is shown. Data are derived from individual subjects and representative of subjects assessed and were consistent across dose levels 2 to 5.

Discussion

Although the capacity of CTLA4 blockade to enhance effector T-cell responses and antitumor immunity has been demonstrated in mouse models, the effects of anti-CTLA4 on Tregs are only now being elucidated. The antitumor effects of anti-CTLA4 have been postulated to be mediated through the depletion of Tregs28 or inhibition of their function.29,30 Here we show that anti-CTLA4 antibody-based treatment does not deplete Tregs, but in fact expands functional Tregs in humans in vivo. Moreover, Tregs were significantly expanded at anti-CTLA4 antibody doses of 1.5 mg/kg or more. Consistent with this finding, Tregs constitutively express higher levels of CTLA4 compared with effector T cells that translocate to cell surface and, therefore, may be more strongly regulated by the inhibitory effects of CTLA4 compared with effector T cells. Constitutive expression of CTLA4 by Tregs may alternatively serve as a sink for binding anti-CTLA4 antibody in vivo. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of the capacity of CTLA4 blockade to induce the proliferation of Tregs in vivo. CTLA4 may therefore play an important role in the homeostasis of Tregs by providing a tonic level of inhibitory signals to these cells that may recognize self-antigens.44

These results clarify seemingly controversial findings. Although mouse models have shown that CTLA4 blockade can increase the number of Tregs in vivo,32 human studies have failed to reach similar conclusions. These latter studies, however, have relied upon surface phenotypes that are not specific for Tregs (such as CD4+CD25+CD62L+) and/or quantitation of FoxP3 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).28,31 Our approach of staining for intracellular FoxP3 protein provides a more direct measure of the frequency of the FoxP3-expressing T cells within the study subjects.

Tregs are composed of at least 2 major subsets: naturally occurring and adaptive.45–47 Naturally occurring Tregs are thymically derived from a distinct FoxP3+ T-cell lineage. In contrast, adaptive human Tregs are thought to arise from mature peripheral FoxP3− CD4+ T cells that have been activated.48 These latter Tregs are induced to express FoxP3 and may mediate their effects through IL-10 and/or TGF-β. Human effector CD4+ T cells can also be induced to transiently express FoxP3 without the development of suppressor function.49,50 Importantly, these studies focus upon human T cells cultured in vitro, whereas our staining focuses upon effects seen in vivo. Our data demonstrate that FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells expanded by our treatment are distinct from activated effector T cells by their low levels of CD69 and CD127 expression, as well as their inability to produce effector cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-10. The phenotype of these cells is, therefore, consistent with human naturally occurring Tregs.37 Finally, we confirm that these expanded Tregs are capable of functionally suppressing effector T cells in vitro. These results suggest that CTLA4 blockade likely induces the proliferation of naturally occurring Tregs.

With the dose escalation of anti-CTLA4 antibody, we demonstrated that a balance between FoxP3− CD4+ effector and FoxP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells exists in vivo. Persistent activation of effector CD4+ T cells was seen only at the highest dose level of anti-CTLA4 antibody studied. In contrast, expansion of Tregs was seen at lower doses. The effects of CTLA4 blockade on FoxP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells may therefore predominate at these lower doses, whereas at higher doses the effector T cells may predominate leading to antitumor and autoimmune clinical effects. This may explain why both clinical responses and side effects have been seen with an antibody dose at or above a threshold of 3 mg/kg as was seen in this and other clinical trials.8,9,12,13,51,52 Although GM-CSF was combined with anti-CTLA4 antibody in this clinical trial to potentially enhance antigen presentation, no significant effects on Tregs and effector CD4+ T cells could be seen at dose level 1. This argues against the treatment effects being related solely to GM-CSF administration.

Other immunotherapies that can induce tumor responses have been shown to induce Tregs, including systemic IL-2 and tumor vaccines.53–55 Our results demonstrate that there exist thresholds where at certain doses, the expansion of Tregs may occur, whereas at an alternate threshold, effector T cells may predominate leading to clinical effects. Determining where a given immunotherapy is on such a continuum will be challenging. Nevertheless, elucidating the requirements for preferentially driving effector T-cell responses will provide important insight into the development of more potent immunotherapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA102303, the UCSF Prostate SPORE NIH P50 CA89520, and UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NCRR UL1 RR024131)

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: B.K. and L.F. designed and performed research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, and drafted the paper; S.O., Y.H., and D.L. performed research and collected data; B.R., J.P.A, and E.J.S. designed research; and V.W. performed the statistical analyses.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.K. discloses the ownership of stock in Medarex. J.P.A. discloses serving as a consultant for Medarex and Bristol Myers Squibb (New York, NY). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lawrence Fong, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of California, San Francisco, 513 Parnassus Avenue, Box 0511, San Francisco, CA 94143; e-mail: lfong@medicine.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CTLA-4 engagement inhibits IL-2 accumulation and cell cycle progression upon activation of resting T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2533–2540. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenwald RJ, Boussiotis VA, Lorsbach RB, Abbas AK, Sharpe AH. CTLA-4 regulates induction of anergy in vivo. Immunity. 2001;14:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egen JG, Kuhns MS, Allison JP. CTLA-4: new insights into its biological function and use in tumor immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:611–618. doi: 10.1038/ni0702-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz AA, Yu TF, Leach DR, Allison JP. CTLA-4 blockade synergizes with tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for treatment of an experimental mammary carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10067–10071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Elsas A, Hurwitz AA, Allison JP. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:355–366. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Elsas A, Sutmuller RP, Hurwitz AA, et al. Elucidating the autoimmune and antitumor effector mechanisms of a treatment based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 blockade in combination with a B16 melanoma vaccine: comparison of prophylaxis and therapy. J Exp Med. 2001;194:481–489. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodi FS, Mihm MC, Soiffer RJ, et al. Biologic activity of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody blockade in previously vaccinated metastatic melanoma and ovarian carcinoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4712–4717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830997100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8372–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribas A, Glaspy JA, Lee Y, et al. Role of dendritic cell phenotype, determinant spreading, and negative costimulatory blockade in dendritic cell-based melanoma immunotherapy. J Immunother. 2004;27:354–367. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck KE, Blansfield JA, Tran KQ, et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2283–2289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attia P, Phan GQ, Maker AV, et al. Autoimmunity correlates with tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6043–6053. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanderson K, Scotland R, Lee P, et al. Autoimmunity in a phase I trial of a fully human anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 monoclonal antibody with multiple melanoma peptides and Montanide ISA 51 for patients with resected stages III and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:741–750. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in immune surveillance and treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, et al. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:2756–2761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viguier M, Lemaitre F, Verola O, et al. Foxp3 expressing CD4+CD25(high) regulatory T cells are overrepresented in human metastatic melanoma lymph nodes and inhibit the function of infiltrating T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1444–1453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang ZZ, Novak AJ, Stenson MJ, Witzig TE, Ansell SM. Intratumoral CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+ T cells in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:3639–3646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller AM, Lundberg K, Ozenci V, et al. CD4+CD25high T cells are enriched in the tumor and peripheral blood of prostate cancer patients. J Immunol. 2006;177:7398–7405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siddiqui SA, Frigola X, Bonne-Annee S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating Foxp3-CD4+CD25+ T cells predict poor survival in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2075–2081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakaguchi S, Ono M, Setoguchi R, et al. Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ natural regulatory T cells in dominant self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:8–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Y, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 in control of the regulatory T cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:457–462. doi: 10.1038/ni1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:389–400. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25(+) regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steitz J, Bruck J, Lenz J, Knop J, Tuting T. Depletion of CD25(+) CD4(+) T cells and treatment with tyrosinase-related protein 2-transduced dendritic cells enhance the interferon alpha-induced, CD8(+) T-cell-dependent immune defense of B16 melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8643–8646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, et al. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Mahony D, Morris JC, Quinn C, et al. A pilot study of CTLA-4 blockade after cancer vaccine failure in patients with advanced malignancy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:958–964. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maker AV, Attia P, Rosenberg SA. Analysis of the cellular mechanism of antitumor responses and autoimmunity in patients treated with CTLA-4 blockade. J Immunol. 2005;175:7746–7754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Curran MA, Allison JP. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bubley GJ, Carducci M, Dahut W, et al. Eligibility and response guidelines for phase II clinical trials in androgen-independent prostate cancer: recommendations from the Prostate-Specific Antigen Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3461–3467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Putnam AL, Vendrame F, Dotta F, Gottlieb PA. CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in human autoimmune diabetes. J Autoimmun. 2005;24:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Small EJ, Tchekmedyian NS, Rini BI, Fong L, Lowy I, Allison JP. A pilot trial of CTLA-4 blockade with human anti-CTLA-4 in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1810–1815. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chattopadhyay PK, Yu J, Roederer M. Live-cell assay to detect antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses by CD154 expression. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavin MA, Torgerson TR, Houston E, et al. Single-cell analysis of normal and FOXP3-mutant human T cells: FOXP3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6659–6664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwarting R, Gerdes J, Niehus J, Jaeschke L, Stein H. Determination of the growth fraction in cell suspensions by flow cytometry using the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol Methods. 1986;90:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sachsenberg N, Perelson AS, Yerly S, et al. Turnover of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection as measured by Ki-67 antigen. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1295–1303. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caruso A, Licenziati S, Corulli M, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of activation markers on stimulated T cells and their correlation with cell proliferation. Cytometry. 1997;27:71–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970101)27:1<71::aid-cyto9>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen XD, Eichler H, Dugrillon A, Piechaczek C, Braun M, Kluter H. Flow cytometric analysis of T cell proliferation in a mixed lymphocyte reaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol Methods. 2003;275:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li L, Godfrey WR, Porter SB, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell lines from human cord blood have functional and molecular properties of T-cell anergy. Blood. 2005;106:3068–3073. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishikawa H, Kato T, Tawara I, et al. Definition of target antigens for naturally occurring CD4(+) CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:681–686. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Garra A, Vieira P. Regulatory T cells and mechanisms of immune system control. Nat Med. 2004;10:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nm0804-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakaguchi S. The origin of FOXP3-expressing CD4+ regulatory T cells: thymus or periphery. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1310–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI20274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:331–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, et al. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25- T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allan SE, Crome SQ, Crellin NK, et al. Activation-induced FOXP3 in human T effector cells does not suppress proliferation or cytokine production. Int Immunol. 2007;19:345–354. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tran DQ, Ramsey H, Shevach EM. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3 T cells by T-cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor-beta dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood. 2007;110:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fong L, Kavanagh B, Hou Y, et al. Combination immunotherapy with GM-CSF and CTLA-4 blockade for hormone refractory prostate cancer: Balancing the expansion of activated effector and regulatory T cells [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl) Abstract 3001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerritsen WR, van den Eertwegh AJ, de Gruijl TD, et al. Biochemical and immunologic correlates of clinical response in a combination trial of the GM-CSF-gene transduced allogeneic prostate cancer immunotherapy and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer (mHRPC) [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl) Abstract 5120. [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Dervliet HJ, Koon HB, Yue SC, et al. Effects of the administration of high-dose interleukin-2 on immunoregulatory cell subsets in patients with advanced melanoma and renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2100–2108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cesana GC, DeRaffele G, Cohen S, et al. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1169–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou G, Drake CG, Levitsky HI. Amplification of tumor-specific regulatory T cells following therapeutic cancer vaccines. Blood. 2006;107:628–636. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]