Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that a problem-solving training program would lower depression, health complaints, and burden, and increase well-being reported by community-residing family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs).

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting

General community.

Participants

Of the 180 people who expressed interest in the study, 113 did not meet eligibility criteria. A consenting sample of family caregivers were randomized into a problem-solving training group (4 men, 29 women; average age, 51.3y) or an education-only control group (34 women; average age, 50.8y). Care recipients included 26 men and 7 women in the intervention group (average age, 36.5y) and 24 men and 10 women in the control group (average age, 37.2y).

Intervention

Problem-solving training based on the D’Zurilla and Nezu social problem-solving model was provided to caregivers in the intervention group in 4 in-home sessions and 8 telephone follow-up calls over the course of their year-long participation. Control group participants received written educational materials and telephone calls at set intervals throughout their 12 months of participation.

Main Outcome Measures

Caregiver depression, health complaints, well-being, and social problem-solving abilities.

Results

Hierarchical linear models revealed caregivers receiving problem-solving training reported significant decreases in depression, health complaints, and in dysfunctional problem-solving styles over time. No effects were observed on caregiver well-being, burden, or constructive problem-solving styles.

Conclusions

Problem-solving training provided in the home appears to be effective in alleviating distress and in decreasing dysfunctional problem-solving styles among family caregivers of persons with TBI. Methodologic limitations and the implications for interventions and future research are discussed.

Keywords: Brain injuries, Caregivers, Problem-solving, Randomized controlled trials, Rehabilitation

Evidence accumulating from decades of empirical research substantiates that many family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injury (TBI) experience considerable distress and compromised quality of life, generally, in the wake of the neurobehavioral changes imposed by TBI.1 To a great extent, this research has been content to describe the various demographic, social, and psychologic correlates of distress, depression, and burden reported by caregivers. Despite this evidence, a recent critical review identified only 4 published studies to date of interventions to alleviate caregiver distress, and it concluded that there is currently no evidence supporting the usefulness of any single psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of persons with TBI.2

Much of the available research on caregiver distress after TBI has been conducted in cross-sectional correlational designs, limiting our ability to make inferences about theory-based psychologic interventions. Yet evidence indicates that considerable variation exists in caregiver reactions. For example, caregivers differ in their subjective appraisal of their role and these appraisals may be directly associated with personal distress.3 Studies of caregiver coping has yielded mixed results: some studies have found that proactive, problem-focused coping may be associated with greater distress,4,5 but other data suggest that families who use these kinds of coping behaviors adjust well over time.6,7

Cognitive-behavioral models of adjustment have proven useful in advancing our theoretical understanding of caregiver distress in related areas. Specifically, there is evidence that differences in caregiver problem-solving abilities may distinguish those who develop pronounced levels of depression, anxiety, and ill health over the initial year of caregiving for a family member with an acquired disability (spinal cord injury [SCI]8). Similar results have been found among caregivers of stroke survivors in cross-sectional9 and prospective research.10 Furthermore, ineffective problem-solving abilities account for more variance in the prediction of caregiver depression than demographic (eg, age, race) and other psychologic (eg, social support) variables among caregivers of persons with TBI,11 SCI,12 and stroke.13

These results are largely consistent with the predominant model of social problem-solving abilities that explicates the usefulness of cognitive-behavioral strategies and beliefs that promote adjustment under routine and stressful circumstances.14 In this prescriptive model, people with a constructive problem-solving style possess skills and beliefs that enable them to regulate their emotions, maintain a positive attitude (for solving problems), and to use rational, instrumental problem-solving strategies. People who rely on dysfunctional strategies, in contrast, typically have difficulties regulating their emotions under routine and stressful conditions; consequently, they are apt to avoid their problems or rely on impulsive, careless, and ineffective methods to solve their problems.

Interventions grounded in the basic principles of this model may be useful in caregiver interventions. Indeed, prior research has documented beneficial effects of problem-solving therapy (PST) in treating depression among persons with chronic disease,15 in promoting adherence to prescribed regimens,16 and in promoting social and interpersonal skills crucial for community reintegration among persons with TBI.17 PST has also shown promise in brief sessions in primary care settings18 and it appears to be effective across treatment modalities (individual, group therapies19).

Problem-solving interventions have gained considerable empirical support for use training family caregivers of stroke survivors.20 A recent multisite clinical trial has provided further evidence that PST can effectively lower caregiver distress.21 The flexible format of PST facilitates its use with caregivers who, because of time constraints and distance, often require novel applications in order to maximize the potential benefits. Caregiver education programs have integrated PST principles in individual, face-to-face sessions22 and in electronic bulletin boards.23 PST was successfully provided in telephone sessions to community-residing caregivers of stroke survivors24 and caregivers of persons with SCI.25 PST has also been used in internet-based sessions to lower parental distress and improve social functioning of children with TBI.26,27

In the present study, we report the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of PST for family caregivers of persons with TBI. Building on a prior demonstration of PST for caregivers of stroke survivors,24 we developed an intervention that would train caregivers in problem-solving principles in their home, circumventing problems with mobility, isolation, and lack of access that typically limit services to caregivers. Consistent with our previous work with family caregivers,28 we tailored PST to help caregivers solve the unique problems of immediate concern to each participating caregiver. Finally, we used a prospective design that would permit us to analyze trajectories of caregiver adjustment in response to PST over a period of 12 months.

We hypothesized that PST would be more effective than an education-only control group in lowering caregiver depression, health complaints, and burden and increasing subjective well-being over time. To further our understanding of the theoretical mechanisms involved in these anticipated changes, we expected caregivers in the PST group to report lower dysfunctional problem-solving styles and increase constructive problem-solving styles over time.

METHODS

Participants

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for demographic and self-report variables for the family caregivers and care recipients who qualified for and consented to participate in the study. The sample consisted mainly of white mothers caring for a son who incurred a TBI. The majority of these women were not employed, and few (15%) received in-home help with their caregiving duties. On average, our participants had been caring for their loved one for over 5 years, although this varied greatly (minimum, 6mo; maximum, 276mo).

Table 1.

Caregiver and Care Recipient Demographic and Initial Status Variables

| Demographics | PST (n=33) (mean ± SD) | Control (n=34) (mean ± SD) | Test | Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers | ||||||

| Age (y) | 51.4±11.1 | 50.8±13.3 | t65=−0.22* | .05 | ||

| Education (y) | 12.9±2.6 | 13.3±2.2 | t65=0.61* | −.15 | ||

| MMSE score | 29.2±1.3 | 28.4±1.8 | t65=−1.93* | .47 | ||

| Caregiving (mo) | 65.7±67.5 | 56.4±73.6 | t65=−0.54* | .13 | ||

| Supervision rating scale | 6.9±2.0 | 6.3±1.9 | t65=−1.41* | .34 | ||

| Depression (CES-D) | 21.5±12.4 | 16.7±11.8 | t65=−1.64* | .40 | ||

| Physical health (PILL) | 13.7±7.3 | 14.2±9.1 | t65=0.28* | −.07 | ||

| Burden | 32.9±11.9 | 32.5±9.6 | t65=−0.17* | .04 | ||

| Well-being (SWLS) | 16.0±8.4 | 21.1±7.8 | t65=2.58† | −.64 | ||

| Problem solving | ||||||

| PPO | 13.3±3.4 | 13.8±3.7 | t65=0.53* | −.13 | ||

| NPO | 14.0±8.0 | 11.5±7.9 | t65=−1.28* | .32 | ||

| RPS | 44.9±14.0 | 49.5±13.9 | t65=1.36* | −.34 | ||

| ICS | 12.4±7.9 | 9.1±6.5 | t65=−1.87* | .46 | ||

| AS | 7.9±5.4 | 5.3±4.6 | t65=−2.16† | .54 | ||

| Frequency | Rel. Frequency (%) | Frequency | Rel. Frequency (%) | |||

| Female | 29 | 88 | 34 | 100 | * | .25 |

| Race | * | .26 | ||||

| White | 31 | 94 | 26 | 85 | ||

| Black | 2 | 6 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Latino | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Employment | * | .23 | ||||

| Unemployed | 23 | 70 | 16 | 47 | ||

| Employed full time | 8 | 24 | 14 | 41 | ||

| Employed part time | 2 | 6 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Help received in home | 5 | 15 | 5 | 15 | * | .01 |

| Care Recipients | ||||||

| Age (y) | 36.5 | 14.0 | 37.2 | 15.0 | t65=0.20* | −.05 |

| Education (y) | 11.9 | 2.8 | 11.9 | 2.4 | t65=−0.09* | .02 |

| MMSE score | 22.3 | 8.5 | 20.3 | 9.3 | t65=−0.91* | .23 |

| FIM score | 110.2 | 35.7 | 111.4 | 40.7 | t65=0.13* | −.03 |

| Day programs (h/wk) | 3.0 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 10.9 | t65=0.81* | −.20 |

| Female | 7 | 21 | 10 | 29 | * | .09 |

| Race | * | .22 | ||||

| White | 31 | 94 | 27 | 79 | ||

| Black | 2 | 6 | 6 | 18 | ||

| Latino | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Employment | * | .07 | ||||

| Unemployed | 32 | 97 | 32 | 94 | ||

| Employed full time | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Employed part time | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | ||

NOTE. P values for categorical variables are based on exact tests. Effect sizes for continuous variables are Cohen d values; effect sizes for categorical variables are ϕ coefficients (or Cramer V where appropriate).

Abbreviations: AS, avoidance style; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies, Depression Scale; ICS, impulsivity/carelessness style; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; NPO, negative problem orientation; PILL, Pennebaker Inventory for Limbic Lanquidness; PPO, positive problem orientation; RPS, rational problem solving; SD, standard deviation; SWLS, Satisfaction With Life Scale.

Not significant.

P<.05.

Care recipients were primarily white men with a high school education. Their average age was 36 years and the average number of hours of participation in out-of-home rehabilitation, day, or recreational program was 3.9 hours a week. Functional deficits were measured by the FIM instrument29 and scores ranged from 18 to 146 (mean, 110.8).

Procedure

Recruitment

We recruited family caregivers of adults with TBI from advertisements, public service announcements in local radio stations, home-health agency referrals, and mailings throughout Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Families were also informed of the study during visits at a rehabilitation hospital located in Birmingham, AL. Interested persons contacted project staff through a toll-free telephone number to discuss basic eligibility requirements. The first author traveled to the interested participant’s home to present details about the study, to confirm eligibility, and to obtain signed consent from both the caregiver and care-recipient.

Caregivers of people with TBI were included in the study if they lived in the same household as the care recipient, provided part-time or full-time care (as determined by the Supervision Rating Scale30) and showed a score of 24 or higher on the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination.31 Caregivers who were not kin were also eligible for the study if they met all other inclusion criteria.

Prospective participants were informed that on consent they would be randomly assigned to either a problem-solving training program or a telephone follow-up program. They were informed that the problem-solving program would involve 4 home visits with a staff member who would teach them problem-solving skills. The participants assigned to the telephone follow-up group would be offered the problem-solving training at the completion of their participation. All participants were informed that they would receive brief telephone calls on a monthly basis, and project staff would be available to them at a toll-free telephone number.

A second appointment was set for a trained examiner to visit with a consenting caregiver and care recipient to individually administer the baseline measures. Contact for all participants was conducted in regularly scheduled intervals with a data collection specialist, and with the assigned interventionist or control group specialist throughout the subsequent 12 months.

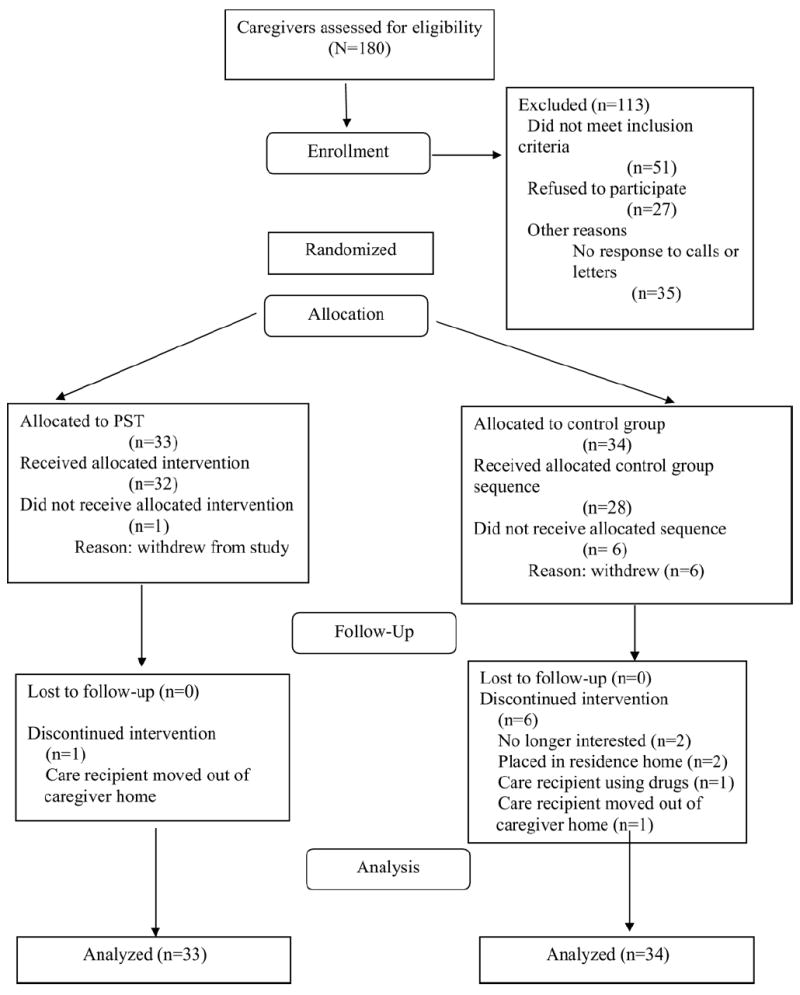

Figure 1 shows the number of caregivers who expressed some interest in the study and who were assessed for eligibility. Of the 180 caregivers who expressed interest in the study, 51 did not meet inclusion criteria, 27 declined to participate once informed of the study, and 35 did not respond to telephone calls or to written correspondence. Internal review board guidelines and privacy assurances prevented any systematic collection of personal information from interested persons who were ineligible or who declined to participate.

Fig 1.

The CONSORT flowchart.

Random assignment

A simple randomization strategy (with a random numbers table) was used by the second author to assign participants to the PST group or to the telephone-based education control group. The second author had no information about the caregiver or care recipient at the time of randomization. As depicted in figure 1, 33 caregivers were randomly allocated to the PST group and 34 were assigned to the control group.

Problem-solving training

In the PST group, contact between the caregiver and an interventionist was made monthly, with in-home problem-solving training sessions occurring at months 1, 4, 8, and 12. Telephone sessions were conducted once a month on the remaining 8 months.

Many aspects of the PST protocol were adapted from previous intervention studies (eg, 15, 24, 25). In the initial face-to-face session in the home, the interventionist discussed the 5 basic principles of the social problem-solving model: identify the problem, brainstorm solutions, critique the solutions, choose and implement a solution, and evaluate the outcome. A card-sort task (presenting problems obtained in a focus group conducted with caregivers of people with TBI) was used by the interventionist to help each caregiver identify the most pressing problem at that time.25,28 The interventionist guided a discussion of feelings the caregiver experienced with the problem and generated a list of possible solutions and goals to address the problem. In the subsequent 3 face-to-face sessions scheduled throughout the year, the interventionist adhered to this general framework to structure the interaction with the caregiver.

Telephone sessions were based, in part, on a format similar to one used in an earlier study with caregivers of stroke survivors.24 The interventionist relied on a worksheet that provided guidelines and prompts for each session. After the initial greeting, the interventionist discussed the value of a positive orientation for solving problems (including a positive, optimistic attitude, and positive emotions) and for finding meaning in their role (including acknowledging the role of caregiving as a challenge), and reviewed any progress on the problems, goals, and planned activities identified in the previous session. This required a review of the problem-solving plan and an evaluation of its relative success. The interventionist then helped the caregiver to identify any current problem and discuss feelings associated with it. The caregiver explored possible solutions and goals with the interventionist, and developed plans, goals, and activities to address the problem and negative feelings associated with it.

The PST protocol was designed to address elements of constructive problem solving (including identifying and prioritizing problems, regulating emotional experiences, attending to negative and positive cognitions, brainstorming and evaluating solutions, using instrumental, rational problem-solving skills).14 The interventionist recorded reactions for each step and notes about the interaction directly on the script for use in future sessions. These notes were reviewed by the first author to ensure that the interventionist was providing training in problem-solving techniques and principles in each session.

The interventionist held a doctoral degree in administration and had ample experience in volunteer work, although he had never been employed as a counselor. The first author trained the interventionist in individual sessions that included instruction in the problem-solving model and the PST group protocol. The first author also supervised the interventionist on 2 home visits. Training involved approximately 30 hours.

Education-only control group

Caregivers assigned to the education-only control group received monthly telephone calls from a control group specialist. During these structured telephone conversations of 10 to 15 minutes in length, previously mailed health-education materials were reviewed.

Assessments

A trained examiner (who had a bachelor’s degree in psychology) administered the instruments at baseline, and again after 4, 8, and 12 months of participation. The examiner typically interviewed the caregiver and care recipient individually. This data collection specialist was unaware of the assigned condition of each caregiver, and information from the assessment batteries was not shared with the interventionist or with the control group specialist. The first author held separate and routine meetings with the interventionist, the control group specialist, and the data collection specialist to supervise their activities. Participants were debriefed at the final assessment.

Descriptive Variables

Demographic data

Caregiver and care-recipient demographic information was obtained.

Functional deficits of the care recipient

The severity of disability of the care recipient was measured with the FIM instrument.29 The FIM has been used as a measure of functional ability in numerous studies that span various populations and data support the measure has adequate validity and reliability.32,33 The instrument that we used contained 17 items that address motor function (eating, grooming, bathing, dressing, toileting, bowel and bladder control, transfers, locomotion) and 5 items that measure cognitive function (communication, social cognition). Each item on the scale ranges from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (complete independence), with lower numbers indicating more functional deficits. Thirteen items reflecting locomotion, transfers, and activities of daily living included an additional scoring option of 0 (does not occur).

Primary Outcome Variables

Depressive symptomatology

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale34 was used to assess symptoms often associated with distress and depression. The instrument has 20 items that are rated on a 5-point, Likert-type scale. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms.

Well-being

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)35 is a 5-item instrument; each item is rated on a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items on the SWLS include: “in most ways my life is close to my ideal,” “the conditions of my life are excellent,” and “I am satisfied with my life.” Higher scores reflect greater subjective well being. The SWLS has evidenced internal consistency (α=.87) and reliability (2mo test-retest coefficient, .82). Correlates with other instruments indicate that the scale is relatively independent of social desirability effects and psychopathology, and it is favorably associated with other measures of life satisfaction.34

Health complaints

The Pennebaker Inventory for Limbic Languidness (PILL)36 was used to assess caregiver’s health complaints. The PILL lists 54 common physical symptoms such as nasal congestion, stiff joints, back pain, and headaches. Respondents stated whether or not they had experienced each symptom in the past week. Positive responses were summed with higher scores reflecting more health complaints. The PILL possesses high reliability (.83) and internal consistency (Cronbach α=.91).

Caregiver burden

A subset of the Caregiver Burden Scale37 was used to assess caregiver’s perceptions of burden. The difficulty subscale measures the difficulty associated with 14 direct, instrumental, and interpersonal demands common to family caregivers. Difficulty of activities are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 [none] to 5 [great deal]). The subscale possesses high reliability (.91) and good internal consistency (Cronbach α range, .87–.91).37

Secondary Outcome Variables

Social problem-solving abilities

The 52-item Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R)38 was used to assess social problem-solving abilities. According to D’Zurilla et al,14 the SPSI-R assesses 2 constructive or adaptive problem-solving dimensions (positive problem orientation, rational problem-solving) and 3 dysfunctional dimensions (negative problem orientation, impulsive/careless style, avoidance style). The 5 major scales, along with sample questions from each scale, are as follows: positive problem orientation, “when I have a problem, I try to see it as a challenge or opportunity to benefit in some positive way from having a problem”; negative problem orientation, “I become depressed and immobilized when I have an important problem to solve”; impulsive/careless style, “when I am attempting to solve a problem, I act on the first idea that occurs to me”; avoidance style, “when a problem occurs in my life, I put off trying to solve it for as long as possible”; and rational problem solving, “when I have a problem to solve, I examine what factors or circumstances in my environment might be contributing to the problem.”

Items on the SPSI-R are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 [not at all true of me] to 4 [extremely true of me]). Participants indicate how they usually respond to problems. The SPSI-R has shown high reliability ranging from .72 to .85 and has been found to be moderately correlated with other external measures of psychologic distress and well-being with significant correlations. D’Zurilla14 has suggested that the positive problem orientation and rational problem-solving scales indicate a constructive problem-solving style, whereas negative problem orientation, avoidance style, and impulsive/careless style indicate a dysfunctional problem-solving style. Both confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses have supported this conceptualization.11,39 We created separate indices of constructive and dysfunctional problem-solving styles from the unweighted sum of items from the appropriate SPSI-R subscales.

Data Analysis

Our first set of analyses examined the comparability of the treatment and control groups on demographic, initial status, and care recipient variables to determine the effectiveness of our randomization procedures in providing roughly equivalent distributions of these variables across treatment conditions. Independent-samples t tests were computed to compare the treatment and control groups on all continuous demographic and initial status variables. Cohen d effect size estimates (using pooled standard deviations) were also computed. For categorical variables, Fisher exact tests were used to compare the treatment and control groups. For 2×2 tables, exact tests were conducted with SPSSa; for all others, tests were conducted through online statistical services by SISA.40 Phi coefficients (or Cramer V coefficients) were calculated as effect size estimates for these categorical variable comparisons.

To test the effects of treatment on major study outcome variables (caregiver depression, physical health, life satisfaction, and problem-solving abilities), we used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) with treatment condition, time, and the interaction of treatment with time as fixed effects. HLM is an excellent tool for analyzing trajectories of change over time in designs that feature repeated outcome measures; it can be used to study group differences in trajectories and to detect possible mediators of intervention effects in these designs.41 Previous work has shown the usefulness of understanding dynamic trajectories of the caregiver experience after SCI8 and stroke,10 and its unique value in studying the effects of PST with caregivers over time.24

Model estimates were obtained using restricted maximum likelihood estimation implemented with the mixed linear models module of SPSS. In these analyses, we used all available data (rather than listwise deletion of subjects with missing data) in the estimation process. In all analyses, a general unstructured variance-covariance matrix was estimated. After the initial model estimation, residuals from the model were examined. In a few cases, observations with extreme residuals were deleted and the model was re-estimated.

RESULTS

Analysis of Baseline Data

Table 1 depicts demographic and initial status data for the PST and control groups, both for caregiver characteristics and care recipient characteristics. In general, the groups were similar on baseline characteristics. However, the distribution of caregiver sex between groups closely approached statistical significance. There were only 4 male caregivers in the study; all 4 had been randomly assigned to the PST condition. The results also suggest that caregivers in the PST group had initially lower levels of satisfaction with life and were more prone to avoidant problem-solving compared with caregivers assigned to the control group.

Table 2 contains correlations among the major outcome variables at initial assessment (for PST and control groups combined). Caregiver depression was positively associated (P<.05) with burden, physical symptoms, and with a negative orientation to problem-solving, and caregiver depression was negatively associated with life satisfaction.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Outcome Variables Assessed at Baseline

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Depression (CES-D) | – | |||||||

| (2) Well-being (SWLS) | −.53† | – | ||||||

| (3) Physical health (PILL) | .63† | −.31* | – | |||||

| (4) Burden | .25* | −.42† | .16 | – | ||||

| (5) PPO | .04 | .01 | .30* | −.06 | – | |||

| (6) NPO | .52† | −.40 | .41† | .33† | −.37† | – | ||

| (7) RPS | −.06 | .10 | .18 | −.02 | .68† | −.23 | – | |

| (8) ICS | .18 | −.14 | .04 | .06 | −.58† | .45† | −.68† | – |

| (9) AS | .15 | −.15 | .08 | .14 | −.59† | .52† | −.45† | .56† |

Caregivers assigned to the PST and control groups did not differ significantly in mean number of months spent in caregiving for the care recipient (see table 1). Given the extreme positive skew of months spent in caregiving, generally, we calculated a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test comparing the 2 conditions. The mean rank for the control group was 31.7 and for the treatment group 36.4. The groups were not significantly different from each other (U=482, P=.32). We also computed Spearman rank-order correlations between months spent in caregiving and the 6 major outcomes at each of the 4 assessment periods. None of the correlations was statistically significant. Correlations ranged from –.04 to .23. Over 70% of the correlations were smaller than .10 in magnitude; only 1 correlation was greater than .20.

Power Analysis

We conducted power analyses based on the procedures developed by Hedeker et al42 for 2-group repeated-measures designs in which a linear treatment by time interaction is expected. Assuming a correlation of .50 between measures across the 4 time points, a sample size of 23 subjects a treatment condition would be needed to detect an effect size of .80 at the final time point (Cohen d metric) with power .80 (2-sided test, α=.05). To detect a smaller effect of .50, a sample size of 55 participants a treatment condition would be needed to achieve the same level of statistical power. With stronger correlations among measures across time periods, statistical power increases substantially. With a between-time correlation of .70, only 34 participants a treatment condition would be needed to detect an effect of .50 with a power of .80. Our present sample size, then, should be adequate for detecting fairly large treatment effects. In our present sample, between-time correlations for outcome measures were generally between .50 and .80, so that in some cases we should have adequate power for detecting more moderate effects.

PST and Control Group Comparisons of Caregiver Adjustment Over Time

Table 3 presents results of the separate HLM analyses for caregiver depression, well-being, health, and burden. Estimated marginal means and their standard errors (SEs) are given for each assessment period. Each outcome measure was modeled as a function of treatment condition, assessment occasion (time), and their interaction. All statistical significance tests were evaluated with an α level of .05 (2-tailed). A significant treatment by time interaction was interpreted as evidence for differential treatment efficacy. All significant interaction effects were followed by separate within-groups trend analyses for each treatment condition.

Table 3.

Results of HLM of Major Outcomes

| Outcome Variables | PST (mean ± SE) | Control (mean ± SE) | Treatment | Treatment by Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (CES-D) | F1,61.8=1.75* | F3,50.9=.26, P=.05 | ||

| T-1 | 21.5±2.02 | 16.1±2.10 | ||

| T-2 | 24.1±2.43 | 18.5±2.35 | ||

| T-3 | 24.7±2.63 | 19.3±2.64 | ||

| T-4 | 17.8±2.28 | 20.7±2.10 d=−.62 | ||

| Time | F3,50.9=1.59* | |||

| Well-being (SWLS) | F1,64.7=6.29, P<.05 | F3,48.6=.52* | ||

| T-1 | 16.0±1.41 | 21.1±1.39 | ||

| T-2 | 16.6±1.51 | 20.2±1.83 | ||

| T-3 | 17.7±1.46 | 21.6±2.01 | ||

| T-4 | 18.7±1.63 | 24.5±2.11 d=−.14 | ||

| Time | F3,48.6=7.82, P<.005 | |||

| Physical health (PILL) | F1,66.3=1.37* | F3,47.6=3.81, P<.05 | ||

| T-1 | 13.7±1.36 | 13.7±1.35 | ||

| T-2 | 17.1±1.59 | 14.1±1.54 | ||

| T-3 | 16.1±1.48 | 11.4±1.47 | ||

| T-4 | 12.5±1.52 | 11.7±1.44 d=.28 | ||

| Time | F3,47.6=5.52, P<.005 | |||

| Burden | F1,63.1=.83* | F3,51.5=.79* | ||

| T-1 | 32.9±1.89 | 32.5±1.86 | ||

| T-2 | 36.3±1.89 | 32.0±1.80 | ||

| T-3 | 33.1±2.15 | 32.0±2.14 | ||

| T-4 | 33.3±2.28 | 31.1±2.11 d=.30 | ||

| Time | F3,51.5=.72* |

Not significant.

Table 3 also presents effect size estimates, in Cohen d metric, for the PST group relative to the control group. The effect sizes are based on standardized mean gain scores from baseline to final assessment for the treatment group relative to the control group, with adjustment for the correlation between repeated measures.43

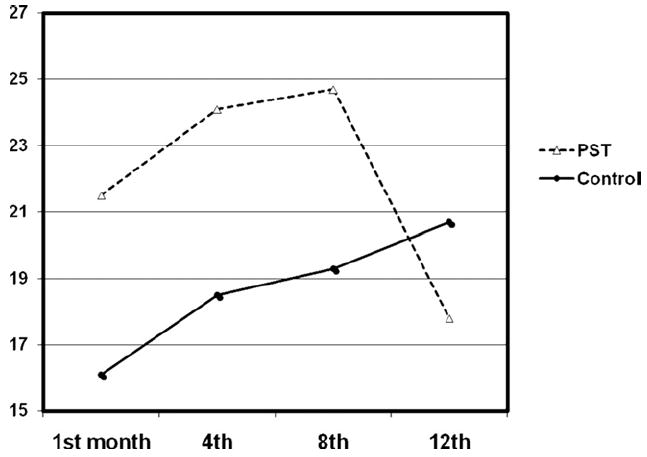

Caregiver depressive symptomatology

The interaction effect of treatment by time in predicting CES-D scores was statistically significant. As depicted in figure 2, caregivers in the PST group reported a significant decrease in depression scores over the 12-month period. A significant linear increase in depression over time was observed among caregivers in the control group (B=1.58, SE=.71; t32.7=2.23, P<.05), and the size of this effect would be considered moderate (d=−.62). For the PST group, a linear decrease in depression over time approached significance (B=−1.19, SE=.62; t23.4=−1.92, P<.1) and a quadratic trend was statistically significant (B=−2.27, SE=.78, t24.8=−2.92, P<.01).

Fig 2.

Significant treatment by time interaction on caregiver depression.

Caregiver well-being

There was no statistically significant interaction between treatment and time on caregiver scores on the SWLS. The main effect for treatment was significant, because caregivers in the control condition reported a higher general well-being. The main effect for time was also significant. Caregivers in both groups reported a significant linear increase in well-being over time (B=1.06, SE=.23; t51.2=4.64, P<.005).

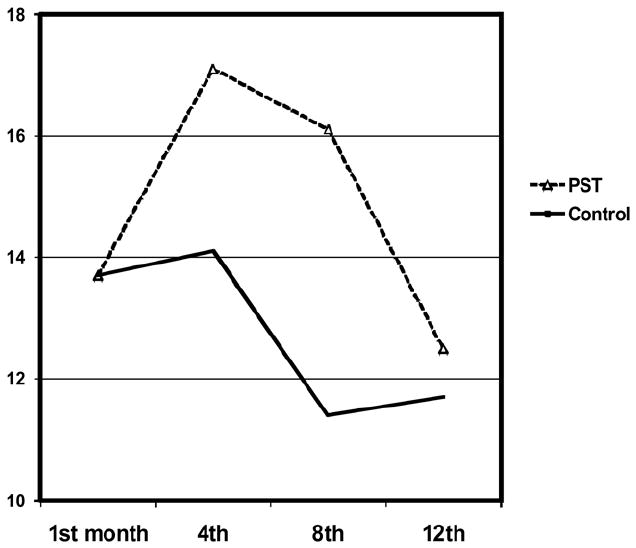

Caregiver health complaints

There was a significant treatment by time interaction effect for caregiver scores on the PILL. Figure 3 depicts the significant decrease in health complaints over time among caregivers receiving PST. Within-group analyses revealed no significant linear trends in reported health symptoms for either group. However, a significant quadratic effect was observed for the treatment group (B=−1.77, SE=.35; t25.1=−5.1, P<.005).

Fig 3.

Significant treatment by time interaction on caregiver health complaints.

Caregiver burden

No statistically significant interaction was found between treatment and time on caregiver burden; the main effects of treatment and time were not significant.

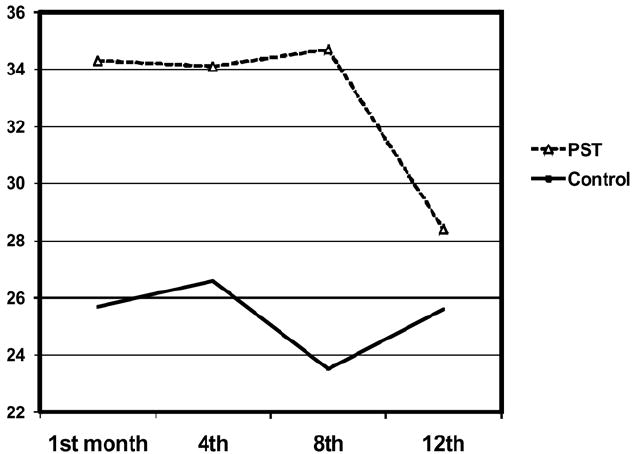

Constructive and Dysfunctional Problem-Solving Styles

Table 4 provides HLM marginal means and SEs for caregiver problem-solving variables. For constructive problem-solving scores, there were no significant effects in the model. For dysfunctional problem-solving scores, there was a significant interaction of treatment with time. Figure 4 illustrates the significant decrease in dysfunctional problem-solving styles over time among caregivers in response to PST. There was no significant trend for the control group over time. However, there was a significant linear decline in dysfunctional problem-solving for the treatment group (B=−2.11, SE=.68; t24.8=−3.1, P<.01). The effect size for the change in dysfunctional problem-solving for the PST group from baseline to final assessment (relative to the control group) would be considered large (d=−1.06).

Table 4.

Results of Hierarchical Modeling of Problem-Solving Styles

| SPSI-R Scales | PST (mean ± SE) | Control (mean ± SE) | Treatment | Treatment by Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructive PS | F1,63.5=.19* | F3,47.9=1.06* | ||

| T-1 | 58.2±2.84 | 63.3±2.80 | ||

| T-2 | 59.2±3.01 | 59.2±2.94 | ||

| T-3 | 60.3±3.90 | 58.5±3.86 | ||

| T-4 | 59.7±3.56 | 63.2±3.37 d=.18 | ||

| Time | F3,47.9=.56* | |||

| Dysfunctional PS | F1,64.8=3.42* | F3,54.1=3.64, P.<05 | ||

| T-1 | 34.3±2.84 | 25.7±2.81 | ||

| T-2 | 34.1±3.15 | 26.6±3.09 | ||

| T-3 | 34.7±3.87 | 23.5±3.82 | ||

| T-4 | 28.4±3.04 | 25.6±2.89 d=−1.06 | ||

| Time | F3,54.1=2.72* |

Abbreviation: PS, problem-solving.

Not significant.

Fig 4.

Significant treatment by time interaction on caregiver dysfunctional problem-solving styles.

Post Hoc Analyses

Possible mediation of treatment impact on depression by problem-solving

Because we observed a differential impact of treatment over time on dysfunctional problem-solving, we hypothesized that changes in dysfunctional problem-solving might account for the observed interaction on depressive symptomatology (ie, mediated moderation). We therefore conducted an HLM analysis predicting depression scores as above, but we included dysfunctional problem-solving scores as a time-varying covariate. The effect for the covariate was statistically significant (F1,117.8=46.5, P<.01). When we controlled for dysfunctional problem-solving, the interaction of treatment and time on depression was no longer statistically significant (F3,50=2.19, P>.10). Because constructive problem-solving did not change differentially by treatment, it is technically not a candidate as a mediator, but for completeness we also included constructive problem-solving as a time-varying covariate in predicting depression. The effect of the covariate was not significant (F1,173.7=.70, P not significant [NS]). The interaction of treatment and time with respect to depression remained statistically significant (F3,50.2=3.32, P<.05).

Analysis of missing data

We examined the missing value patterns for the 9 major outcome variables (depression, well-being, physical health, burden, 5 problem-solving variables) over all testing occasions. The subject by time by outcomes matrix was 81% complete for the whole sample (80.3% for the PST group, 81.6% for the control group). Little’s MCAR (missing completely at random) test44 provided support for the hypothesis that missing values occurred completely at random ( , P=.83). We also compared the 7 withdrawn participants to all others (using independent-samples t tests) on initial status on outcome variables. There were no significant differences on any outcome variable.

Analysis of change of care-recipient functional abilities

We entertained the possibility that observed changes in any outcome variable may be attributable in part to significant changes in care recipient functional abilities over time. We examined possible changes in care-recipient FIM scores from baseline to time 4 using HLM. The control group mean FIM score ± SE at baseline was 111.4±6.6 and at the final assessment was 109.1±6.6. For the PST group, the mean FIM at baseline was 110.2±6.7 and at the final assessment was 108.3±6.8. There were no statistically significant effects for treatment (F1,64.6=.01, P=NS), time (F1,49.3=1.81, P=NS), or the interaction of treatment with time (F1,49.3=.01, P=NS). Thus, group differences on outcome variables could not be attributed to differential FIM change.

DISCUSSION

Caregivers who received PST reported a significant reduction in depression and health complaints over the year, and they also reported a significant decrease in dysfunctional problem-solving styles. These results converge with other evidence supporting the usefulness of PST for family caregivers of persons with chronic disease and disability.9,21,24-27 To our knowledge, this is the first RCT to document beneficial effects of a psychologic intervention over a 12-month period for family caregivers of persons with TBI. Furthermore, the current study converges with other available research24,26,27 to indicate that PST may be effectively delivered in telehealth applications to people who have barriers that limit their access to health care services. Studies that report clinical effectiveness are necessary to justify the greater use of telehealth applications in service delivery programs and to attract support from policy-makers.45

The results of the current study expand our appreciation of PST and its possible effects. For example, this is the first study to show beneficial effects of PST on participant health complaints. In light of the documented health problems of family caregivers,46 these data are encouraging. It should be noted that the measure of health complaints relied on self-report; despite supportive evidence linking self-reported health complaints with objective indicators of health status (eg, mediation use, days sick),36 these findings should be interpreted with caution.

These findings also address issues that exist in the problem-solving literature. Unlike other caregiver intervention research programs that espoused PST yet essentially ignored the implications of the social problem-solving model,47 the problem-solving intervention in the present study was designed to provide training in abilities associated with the problem orientation component and in problem-solving skills, as delineated in the social problem-solving model.14 Nezu48 has argued that the problem orientation component must be addressed for PST to be effective and a recent meta-analysis of the PST literature supports this contention.49 The current intervention was also tailored to meet the unique needs and concerns of each caregiver, thereby increasing the relevance, credibility, and usefulness of PST for each participant.25,28

The effects of PST were not mediated by possible changes in care-recipient functional ability over time. Post hoc analyses indicated that the benefits of PST were attributable in part to decreases in dysfunctional problem-solving styles. Yet no changes were observed in the positive, adaptive problem solving styles. These data indicate that decreases in caregiver depression and health complaints may be associated with decreases in negative, maladaptive problem-solving strategies. Elliott and Hurst19 speculate that an absence of dysfunctional problem-solving styles may exert a greater influence on adjustment than an increased presence of constructive problem-solving abilities.

Correlational analyses revealed a positive relationship between caregiver depression and burden, physical health complaints, and a negative approach to problem-solving. Caregiver depression was also negatively associated with life satisfaction. From this pattern, one might expect a treatment effect for all four outcome variables; however, this was not the case. PST had no apparent effects on caregiver satisfaction with life or on caregiver burden. Caregivers in the control group reported a steady increase in depression over time; however, they also reported a steady increase in life satisfaction over time. The lack of effects on caregiver burden may reflect stressful realities of the caregiver experience, generally. Although the difficulties of caregiver tasks may remain stressful and burdensome (and burden is often construed as a proxy for stress),3 there is sufficient empirical evidence indicating that social problem-solving abilities are predictive of distress and adjustment under routine and stressful circumstances.14,19 Collectively, these data underscore the need to appreciate the complexities of caregiver adjustment, and the dynamic trajectory of the caregiving career, generally.

It is possible that our results may have been influenced by unmeasured motivational factors of the caregivers who volunteered to participate in the study. Volunteer biases are an intrinsic problem in RCTs.50 Although randomization can be an effective means of distributing motivational biases between the assigned groups, we have no meaningful information about the potential participants who expressed no interest in the study, or who declined to participate. Consequently, we do not know the degree to which the current sample is representative of most community-residing family caregivers of persons with TBI. Moreover, there is no routine treatment-as-usual for community-residing family caregivers of persons with TBI, so the control group experience of the current study may not represent ideal characteristics expected of a control condition in traditional RCT designs. This is a recurring problem in community-based intervention research of persons who live with chronic, disabling conditions.51

Study Limitations

The sample size resulted in a relatively modest level of power for our analyses. We did not use a correction procedure for α inflation for our analyses. Replication with a larger sample is warranted. We did not collect information on any other psychologic support provided to the caregivers in our sample. We do not know if these kinds of activities may have affected our results. The high rate of participant retention suggests that the protocols were well received by caregivers. Analyses of exit questionnaires revealed no meaningful differences in degree of satisfaction between participants assigned to the 2 groups. Because participant attrition is a common problem in longitudinal research, much consideration was placed on the development of a protocol that was attentive and respectful of the caregiver’s needs for time, privacy, efficiency, and perceived support.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study indicate that PST can be effectively provided to caregivers of persons with TBI in monthly telephone sessions supplemented by occasional face-to-face sessions in the residence. Depression and health complaints may be particularly responsive to PST over a 12-month period. Evidence from another RCT has shown that PST through telephone sessions is associated with decreased depression reported by caregivers of stroke survivors over 12 weekly sessions.24 The pattern of results in the current study implies that the therapeutic benefits of PST were apparent between the eighth and twelfth month assessments. There is a general recognition that in some cases, beneficial effects of psychologic interventions do not occur in a linear fashion, but may be realized in discrete stages (particularly among people who are coping with extreme stressors).52 Further research is needed to refine current knowledge about the dosage of PST that is necessary and sufficient to produce meaningful, therapeutic changes in family caregivers.19

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute for Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant no. H133A02050), by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - National Center for Injury Prevention (grant no. R49/CE000191), and by the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (grant no. T32 HD07420).

Footnotes

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the authors or upon any organization with which the authors are associated.

Supplier Version 15; SPSS, 233 S Wacker Dr, 11th Fl, Chicago, IL 60606.

Contributor Information

Patricia A. Rivera, Birmingham Veterans Administration Medical Center, Birmingham, AL.

Timothy R. Elliott, Department of Educational Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Jack W. Berry, Injury Control Research Center, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL.

Joan S. Grant, University of Alabama School of Nursing, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL.

References

- 1.Perlesz A, Kinsella G, Crowe S. Impact of traumatic brain injury on the family: a critical review. Rehabil Psychol. 1999;44:6–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boschen K, Gargaro J, Gan C, Gerber G, Brandys C. Family interventions after acquired brain injury and other chronic conditions: a critical review of the quality of the evidence. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22:19–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chwalisz K. The perceived stress model of caregiver burden: evidence from the spouses of persons with brain injuries. Rehabil Psychol. 1996;41:91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chronister J, Chan F. A stress process model of caregiving for individuals with traumatic brain injuries. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51:190–201. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wade SL, Borawski E, Taylor G, Drotar D, Yeates K, Stancin T. The relationship of caregiving coping to family outcomes during the initial year following pediatric traumatic injury. J Consul Clin Psychol. 2001;69:406–15. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinsella G, Ong B, Murtagh D, Prior M, Sawyer M. The role of the family for behavioral outcome in children and adolescents following traumatic brain injury. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:116–23. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivara JM, Jaffe KM, Polissar NL, Fay GC, Liao S, Martin KM. Predictors of family functioning and change 3 years after traumatic brain injury in children. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:754–64. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliott T, Shewchuk R, Richards JR. Family caregiver social problem-solving abilities and adjustment during the initial year of the caregiving role. J Couns Psychol. 2001;48:223–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera PA, Elliott TR, Berry JW, Oswald K, Grant J. Family caregivers of women with physical disabilities. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2006;13:431–40. doi: 10.1007/s10880-006-9043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant J, Elliott T, Weaver M, Glandon G, Giger J. Social support, social problem-solving abilities, and adjustment of family caregivers of stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera P, Elliott T, Berry J, Oswald K, Grant J. Predictors of caregiver depression among community-residing families living with traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreer L, Elliott T, Shewchuk R, Berry J, Rivera P. Family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: predicting caregivers at risk for depression. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52:351–7. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.52.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant J, Weaver M, Elliott T, Bartolucci A, Giger J. Family caregivers of stroke survivors: characteristics of caregivers at-risk for depression. Rehabil Psychol. 2004;49:172–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social problem solving: theory and assessment. In: Chang E, D’Zurilla TJ, Sanna LJ, editors. Social problem solving: theory, research, and training. Washington (DC): American Psychological Assoc; 2004. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consul Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1037–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rath JF, Hennessy JJ, Diller L. Social problem solving and community integration in postacute rehabilitation outpatients with traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2003;48:137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson D. Randomized controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 1995;310:441–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott T, Hurst M. Social problem solving and health. In: Walsh WB, editor. Biennial review of counseling psychology. Vol. 1. New York: Psychology Pr; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lui MH, Ross FM, Thompson DR. Supporting family caregivers in stroke care: a review of the evidence for problem solving. Stroke. 2005;36:2514–22. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185743.41231.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahler O, Fairclough D, Phipps S, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:272–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houts PS, Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Butcher JA. The prepared family caregiver: a problem-solving approach to family caregiver education. Patient Educ Counsel. 1996;27:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucher J, Houts P, Nezu CM, Nezu A. Improving problem-solving skills of family caregivers through group education. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1999;16:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, Bartolucci AA, Giger JN. A telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke. 2002;33:2060–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020711.38824.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivera PA, Shewchuk R, Elliott T. Project FOCUS: using video-phones to provide PST to family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury. Top SCI Rehabil. 2003;9:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wade SL, Carey J, Wolfe CR. An online family intervention to reduce parental distress following pediatric brain injury. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:445–54. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wade SL, Carey J, Wolfe CR. The efficacy of an online cognitive-behavioral family intervention in improving child behavior and social competence in pediatric brain injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51:179–89. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott T, Shewchuk R. Problem solving therapy for family caregivers of persons with severe physical disabilities. In: Radnitz C, editor. Cognitive-behavioral interventions for persons with disabilities. New York: Jason Aronson; 2000. pp. 309–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. Guide for the use of the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation. Version 5.0. Buffalo: State Univ New York at Buffalo Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boake C. Supervision rating scale: a measure of functional outcome from brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:765–72. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. J Psychol Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodds TA, Martin DP, Stolov WC, Deyo RA. A validation of the functional independence measure and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:531–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granger CV, Cotter AC, Hamilton BB, Fiedler RC. Functional assessment scales: a study of persons after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pennebaker JW. The psychology of physical symptoms. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberst MT, Thomas SE, Gass KA, Ward SE. Caregiving demands and appraisal of stress among family caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 1989;12:209–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social problem-solving inventory-revised (SPSI-R): technical manual. North Tonawanda: Multi-health Systems; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson M, Elliott T, Neilands T, Morin SF, Chesney MA. A social problem-solving model of adherence to HIV medications. Health Psychol. 2006;25:355–63. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uitenbroek DG. [June 27, 2007];SISA Fisher 2 ×5. 2000 Available from: http://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/distributions/binomial.htm.

- 41.Laurenceau JP, Hayes AM, Feldman GC. Some methodological and statistical issues in the study of change processes in psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:682–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Waternaux C. Sample size estimation for longitudinal designs with attrition: comparing time-related contrasts between two groups. J Educ Behav Stat. 1999;24:70–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 49. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001. Practical meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little RJ. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller EA. Solving the disjuncture between research and practice: telehealth trends in the 21st century. Health Policy. 2007;82:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan J. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis Psychol Bull. 2003;129:946–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wisniewski SR, Belle S, Coon D, et al. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): project design and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:375–84. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nezu A. Problem solving and behavior therapy revisited. Behav Ther. 2004;35:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, Bhullar N, Schutte NS. The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tucker JA, Roth DL. Extending the evidence hierarchy to enhance evidence-based practice for substance abuse disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:918–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elliott TR. Registering randomized clinical trials and the case for CONSORT. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:511–8. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.6.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayes AM, Laurenceau JP, Feldman G, Strauss JL, Cardaciotto L. Change is not always linear: the study of nonlinear and discontinuous paths of change in psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:715–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]