Abstract

Hemostasis and thrombosis (blood clotting) involve fibrinogen binding to integrin αIIbβ3 on platelets, resulting in platelet aggregation. αvβ3 binds fibrinogen via an Arg-Asp-Gly (RGD) motif in fibrinogen's α subunit. αIIbβ3 also binds to fibrinogen; however, it does so via an unstructured RGD-lacking C-terminal region of the γ subunit (γC peptide). These distinct modes of fibrinogen binding enable αIIbβ3 and αvβ3 to function cooperatively in hemostasis. In this study, crystal structures reveal the integrin αIIbβ3–γC peptide interface, and, for comparison, integrin αIIbβ3 bound to a lamprey γC primordial RGD motif. Compared with RGD, the GAKQAGDV motif in γC adopts a different backbone configuration and binds over a more extended region. The integrin metal ion–dependent adhesion site (MIDAS) Mg2+ ion binds the γC Asp side chain. The adjacent to MIDAS (ADMIDAS) Ca2+ ion binds the γC C terminus, revealing a contribution for ADMIDAS in ligand binding. Structural data from this natively disordered γC peptide enhances our understanding of the involvement of γC peptide and integrin αIIbβ3 in hemostasis and thrombosis.

Introduction

Integrins are formed from α and β subunits, each with a large extracellular domain and a single, more C-terminal transmembrane domain. The subunits come together in a large interface between the α subunit β propeller domain and the β subunit β I domain to form the ligand-binding head. Other domains form upper and lower legs in each subunit to connect the head to the membrane. Integrins have an overall bent conformation in the low affinity state, with the bend between the upper and lower legs. Upon activation, integrins extend, and a major reorientation at the interface between the β I and hybrid domains occurs that is linked to remodeling of the ligand-binding site in the β I domain (Luo et al., 2007). The β I domain has three metal ion–binding sites, with a Mg2+ ion in the central metal ion–dependent adhesion site (MIDAS) flanked by two Ca2+ ions, one of which is in a site termed adjacent to MIDAS (ADMIDAS). Structures of αvβ3 and αIIbβ3 bound to cyclic RGD-like peptides show binding across the α subunit β propeller interface with the β subunit I domain. The Asp side chain coordinates the Mg2+ ion at the β subunit I MIDAS, whereas the Arg side chain binds to Asp residues in the α subunit β propeller domain (Xiong et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2004).

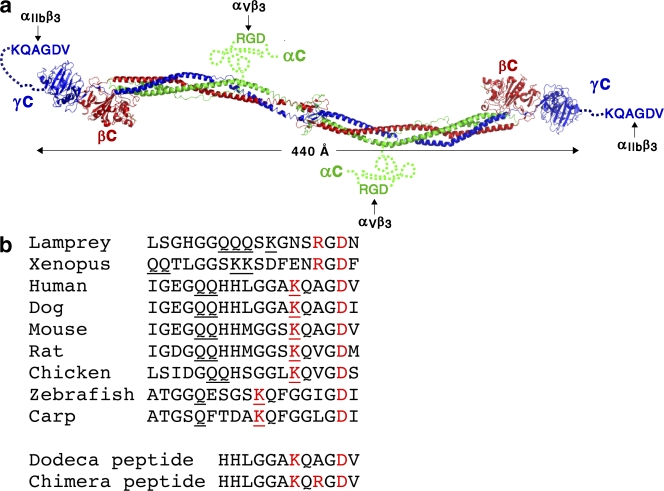

Early in hemostasis and thrombosis, the integrin αIIbβ3 on platelets is activated and binds to its ligand fibrinogen. Fibrinogen is a dumbbell-shaped molecule (Fig. 1 a). Integrin αIIbβ3 binds specifically to the distal ends of the dimeric fibrinogen molecule in a natively unstructured region at the C terminus of the γ subunit (γC peptide; Yang et al., 2001). The large separation between the two αIIbβ3-binding sites on fibrinogen of ∼440 Å is well suited for cross-linking of platelets, which results in platelet aggregation and formation of platelet plugs in hemostasis and thrombosis. In a later event in hemostasis, cleavage of peptides from the N termini of the fibrinogen α and β subunits stimulates assembly of fibrinogen into fibrin. Yet later, adjacent fibrinogen molecules within fibrin are cross-linked through their γC peptides by the factor XIIIa transglutaminase (Hawiger, 1995; Bennett, 2001).

Figure 1.

Fibrinogen and its C-terminal γ subunit sequences. (a) Ribbon diagram of fibrinogen (Yang et al., 2001) with α, β, and γ subunits in green, red, and blue, respectively, and natively unstructured C-terminal regions of the α and γ subunits (Yang et al., 2001; Doolittle and Kollman, 2006) that contain RGD and KQAGDV sequences shown schematically as dashed lines. (b) The C-terminal sequence of the γ subunit in different species. Basic and acidic residues that are important for binding to fibrinogen as shown here for human and implicated for other species are shown in red. Gln and Lys residues known (human and lamprey; Strong et al., 1985) or implicated (other species) to mediate fibrinogen cross-linking catalyzed by factor XIIIa transglutaminase are underlined. Sequence accession (GI) numbers of the relevant fibrinogen splice variants are 70906437, 73977998, 19527078, 61098186, 45384500, 120145, and 120143.

One of the best established paradigms in integrin biology is the recognition of protein ligands through Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequences, the majority of which are present within flexible loop regions. Eight vertebrate integrins, including αIIbβ3 and αvβ3, recognize RGD sequences in ligands, and crystal structures are beginning to reveal how RGD is recognized, at least in cyclic peptides (Xiong et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2004). However, the γC region of fibrinogen lacks an RGD motif. Studies on synthetic peptides show specific binding of αIIbβ3 to the γC C-terminal dodecapeptide, a gradual loss of activity when the dodecapeptide is truncated from its N terminus, and complete loss of activity when the C-terminal pentapeptide is removed. The minimal peptide with inhibitory activity was found to be the C-terminal pentapeptide, QAGDV (Kloczewiak et al., 1984, 1989). Furthermore, removal of the γC QAGDV sequence but not of two RGD sequences in fibrinogen abolishes binding to αIIbβ3 (Farrell et al., 1992; Holmback et al., 1996). Thus, although RGD peptides, including those corresponding to sequences in fibrinogen, can inhibit binding of αIIbβ3 to fibrinogen, the γC peptide is the biologically important recognition site for αIIbβ3 within fibrinogen. In contrast to αIIbβ3, integrin αvβ3 on endothelial cells binds to a distinct site containing an RGD motif in the fibrinogen α subunit (Cheresh et al., 1989; Smith et al., 1990; Doolittle and Kollman, 2006). This cooperative interaction between αIIbβ3 and αvβ3 integrins allows the platelet/fibrinogen thrombus formed by activation of αIIbβ3 to be anchored on endothelium through αvβ3 (Cheresh et al., 1989; Smith et al., 1990).

Whether RGD and γC peptides bind to distinct or similar sites on αIIbβ3 is controversial. Several studies show competition for the same binding site (Lam et al., 1987; Santoro and Lawing, 1987; Bennett, 2001). Interestingly, although γC and RGD peptides were found to cross-compete, a γC dodecapeptide was photo–cross-linked only to the αIIb subunit, whereas a RGD hexapeptide was cross-linked to both the αIIb and β3 subunits (Santoro and Lawing, 1987). Binding has been described of RGD and γC peptides to distinct, nonoverlapping, allosterically linked sites (Hu et al., 1999). RGD and RGD-like peptides have also been described to bind to distinct sites on αIIbβ3 (Cierniewski et al., 1999). Furthermore, γC peptide was reported to cross-link to an αIIb site (D'Souza et al., 1990) that is distal from the binding site for RGD shown in crystal structures (Xiao et al., 2004).

Because of the biological and clinical importance of the γC peptide in hemostasis and thrombosis, there has been great interest in determining its biologically relevant integrin-bound conformation. However, in multiple crystal structures of fibrinogen and its C-terminal γ subunit fragment, the γC peptide is disordered (Pratt et al., 1997; Spraggon et al., 1997; Yee et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2001; Kostelansky et al., 2002). Crystals of the γC peptide fused to lysozyme or glutathione S–transferase reveal different conformations (Donahue et al., 1994; Ware et al., 1999) that are unrelated to the integrin-bound conformation described here. Nuclear magnetic resonance measurements of γC interaction with αIIbβ3 provided limited information (Mayo and Fan, 1996). In the absence of appreciation of the features important for specific recognition of γC by αIIbβ3, pharmaceutical development of antithrombotics began with compounds with RGD or KGD motifs. Subsequent synthesis and screening then focused on obtaining compounds that were selective for αIIbβ3 compared with other integrins that recognize RGD, such as αvβ3 and α5β1 (Scarborough and Gretler, 2000). Two RGD-based drugs, a small molecule, tirofiban, and a cyclic peptide, eptifibatide, are currently used clinically to prevent thrombosis, and their complex structures with αIIbβ3 have been determined (Xiao et al., 2004).

In this study, we investigate how the γC peptide and a related peptide containing the RGD sequence present in lamprey γC bind to αIIbβ3. The results reveal the biologically important interface between γC peptide and αIIbβ3 and unexpected features of the integrin recognition of ligands, including a direct role for ADMIDAS in ligand recognition.

Results

Overall complex structure

We soaked human γC deca- and dodecapeptides into αIIbβ3 headpiece/Fab crystals (Xiao et al., 2004). Examination of fibrinogen γ subunit sequences in a diverse range of vertebrates (fibrinogen is found only in vertebrates) revealed that RGD is found in γC in frog and lamprey (Fig. 1 b). This observation, which, to our knowledge, is previously unremarked and therefore was a surprise to us, suggests an obvious evolutionary pathway from promiscuous integrin recognition of RGD in the primordial jawless vertebrate the lamprey to monospecific integrin recognition of non-RGD sequences in most higher vertebrates. Therefore, for comparison to human γC, we also soaked crystals with chimeric deca- or dodecapeptides containing the RGD sequence present in lamprey γC (Fig. 1 b). Structures were determined at 2.4–2.8-Å resolution (Table I), and previous structures with antagonists were rerefined to lower Rfree (Table II). The structures contain the β propeller domain in the αIIb subunit; the I, hybrid, plexin-semaphorin integrin, and integrin EGF-like (I-EGF) domain 1 in the β3 subunit; 15 carbohydrate residues; and bound ligand and Fab. The structures all have an open headpiece (i.e., with the hybrid domain swung out) and the β I domain in the high affinity state (Xiao et al., 2004)

Table I. αIIbβ3 γC peptide complex x-ray diffraction and refinement data.

| Peptide sequence | HHLGGAKQAGDV | LGGAKQAGDV | HHLGGAKQRGDV | LGGAKQRGDV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 |

| Unit cell (a, b, c) (Å) | 148.3, 148.3, 176.6 | 148.4, 148.4, 177.2 | 148.5, 148.5, 176.4 | 148.3, 148.3,176.8 |

| α, β, γ (degree) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07223 | 1.07223 | 1.07223 | 1.07223 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.5 | 50–2.8 | 50–2.6 | 50–2.4 |

| Number of reflections (total/unique) | 557,015/77,023 | 362,650/55,536 | 416,764/68,878 | 609,049/87,704 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8/100b | 99.4/99.6b | 98.5/87.4 | 99.7/99.0b |

| I/σ (I) | 17.6/3.5b | 16.2/2.8b | 19.1/2.2b | 17.3/2.3b |

| Rmerge (%) | 8.6/55.2bb | 10.5/62.3b | 8.5/43.3 | 9.0/56.9b |

| Number of atoms (protein/water/other) |

10,538/1,043/205 | 10,446/557/205 | 10,515/1,332/205 | 10,537/1,142/205 |

| Rmsd bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Rmsd bond angles (degree) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Rwork (%) | 14.8 | 15.6 | 14.1 | 14.8 |

| Rfree (%) | 19.0 | 20.4 | 19.0 | 19.3 |

| Ramachandran statistics (% favored/allowed/outlier)a |

96.9/3.0/0.1 | 96.5/3.4/0.1 | 97.1/2.6/0.2 | 97.1/2.7/0.2 |

| PDB code | 2VDO | 2VDP | 2VDQ | 2VDR |

Rmerge = ΣH Σi |Ii(h) − <I(h)>|/ΣHΣi Ii(h), where Ii(h) and <I(h)> are the ith and mean measurement of the intensity of reflection, h. Rwork = ΣH||Fobs (h)| − |Fcalc (h)||/ΣH|Fobs (h)|, where Fobs (h) and Fcalc (h) are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. No I/σ cutoff was applied. Rfree is the R value obtained for a test set of reflections consisting of a randomly selected 5% subset of the data set excluded from refinement.

Determined with RAMPAGE (Lovell et al., 2003).

These numbers correspond to the last resolution shell.

Table II. Rerefined αIIbβ3 complex x-ray diffraction and refinement data.

| Ligand | Native1 | Native2 | Tirofiban | Eptifibatide | L-739758 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 |

| Unit cell (a, b, c) (Å) | 148.9, 148.9, 176.1 | 148.9, 148.9, 176.4 | 148.6, 148.6, 177.2 | 149.6, 149.6, 175.7 | 149.2, 149.2, 176.2 |

| α, β, γ (degree) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90,120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9793 | 0.9793 | 0.9760 | 0.9760 | 0.9793 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.8 | 50–2.75 | 50–2.9 | 50–2.9 | 50–3.1 |

| Number of reflections (total/unique) |

400,460/55,875 | 442,121/62,512 | 330,745/50,662 | 357,439/50,647 | 263,308/41,586 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9/99.8b | 99.9/100b | 99.7/98.2b | 100/100b | 99.8/99.7b |

| I/σ (I) | 14.0/3.1b | 20.0/3.0b | 12.1/2.0b | 14.9/2.7b | 12.1/2.7b |

| Rmerge (%) | 13.0/68.1b | 9.6/59.8b | 13.9/57.8b | 11.7/61.5b | 14.0/55.8b |

| Number of atoms (protein/water/other) |

10,404/612/210 | 10,461/1,129/210 | 10,363/355/235 | 10,385/364/223 | 10,348/98/240 |

| Rmsd bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Rmsd bond angles (degree) | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Rwork (%) | 16.1 | 14.4 | 16.7 | 16.3 | 18.1 |

| Rfree (%) | 20.4 | 19.1 | 20.6 | 21.3 | 22.0 |

| Ramachandran statistics (% favored/allowed/outlier)a |

97.3/2.5/0.2 | 97.2/2.5/0.3 | 96.5/3.3/0.2 | 96.8/2.9/0.2 | 96.5/3.3/0.2 |

| Obsolete PDB code | 1TY3 | 1TXV | 1TY5 | 1TY6 | 1TY7 |

| New PDB code | 2VDK | 2VDL | 2VDM | 2VDN | 2VC2 |

Rmerge = ΣH Σi |Ii(h) − <I(h)>|/ΣHΣi Ii(h), where Ii(h) and <I(h)> are the ith and mean measurement of the intensity of reflection, h. Rwork = ΣH||Fobs (h)| − |Fcalc (h)||/ΣH|Fobs (h)|, where Fobs (h) and Fcalc (h) are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. No I/σ cutoff was applied. Rfree is the R value obtained for a test set of reflections consisting of a randomly selected 5% subset of the data set excluded from refinement.

Determined with RAMPAGE (Lovell et al., 2003).

These numbers correspond to the last resolution shell.

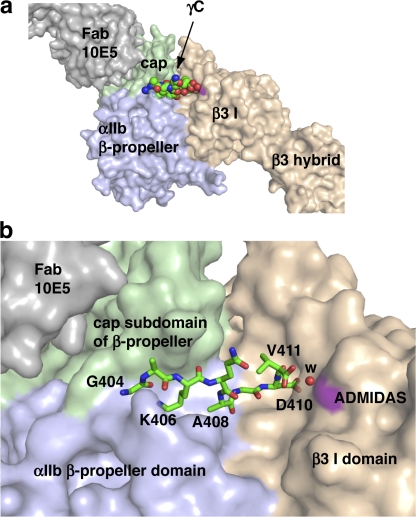

The γC peptide binds at the interface between the αIIb β propeller and β3 I domains (Fig. 2 a). The binding site overlaps with, but is more extensive on both the α and β subunits, than previously described for cyclic RGD peptides (Xiong et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2004). The contacts on the β3 subunit include not only MIDAS but also a novel water-mediated coordination of the γC C terminus with ADMIDAS, as described in more detail in the next section. The γC peptide contacts with αIIb lie in a groove between two long loops that connect blades (β sheets of the αIIb β propeller) 2 and 3 and blades 3 and 4. The cap subdomain of the β propeller (Xiao et al., 2004) forms one side of this groove (Fig. 2 b). In the region of the γC peptide N terminal to residue 404, extension along the groove is blocked by contact of γC residue Leu-402 with a neighboring molecule in the crystal lattice, and residues 400–403 have weak electron density and extend toward solvent. Therefore, we limit our structural analysis to γC octapeptide residues 404–411, which show strong electron density in omit maps, intimately contact αIIbβ3 (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 a), and have essentially identical conformations in crystals soaked with γC peptides 400–411 and 402–411 (Table I).

Figure 2.

The binding pocket for the γC peptide. (a) Overview. (b) Detail. αIIbβ3 and 10E5 Fab are shown as solvent-accessible surfaces, with the γC peptide shown in spheres (a) or sticks (b). Lys-406 and Asp-410 are the most buried residues. The surface at the ADMIDAS metal is colored purple (as is that at the MIDAS, which is not visible), and the water coordinating the Val-411 α-carboxyl to the ADMIDAS is a red sphere. Figures were made with Pymol (DeLano Scientific).

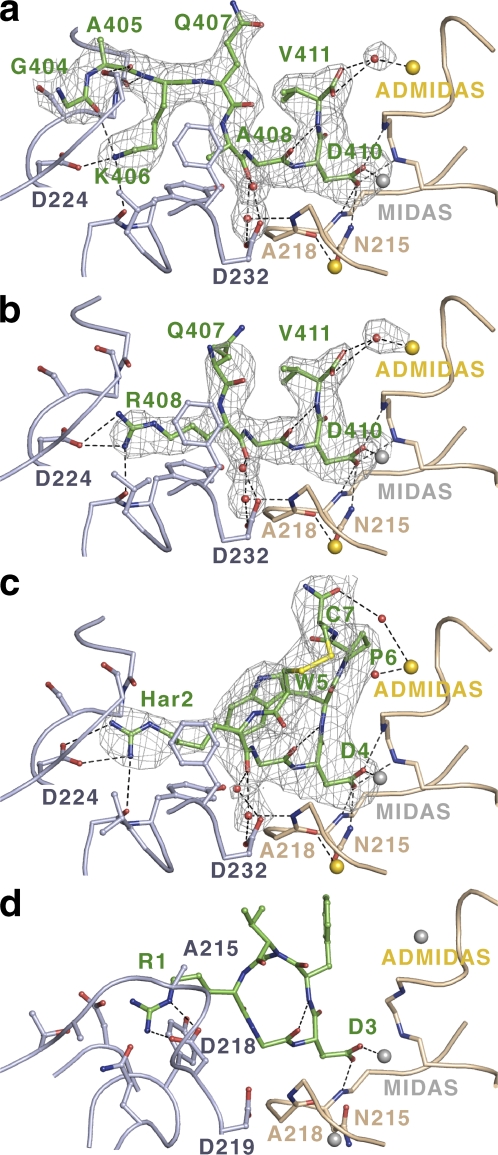

Figure 3.

Binding of the linear γC and RGD chimera peptides and comparison with cyclic peptides. Ligand, α subunit, and β subunit are shown in green, light blue, and beige, respectively, with O, N, and S atoms in red, blue, and yellow, respectively. Water molecules are red spheres. Ca2+ ions are gold spheres, and Mg2+ ions (a–c) or Mn2+ ions (d) are silver spheres. Fc-Fo omit maps after refinement in the absence of ligands and the displayed water molecules are contoured at 3σ. The complexes are αIIbβ3 (a–c) with γC dodecamer (a) or chimera decamer (b) peptides, disulfide-cyclized eptifibatide peptide (c), or αvβ3 with backbone-cyclized cilengitide peptide (d; Xiong et al., 2002). One-letter code is used for residues except for homoarginine (Har). Residue C7 in eptifibatide (c) is amidated.

Surface representations of the binding site show not only the groove in which the γC peptide lies but two deeper pockets within this groove (Fig. 2 b). The penultimate residue in the γC peptide, Asp-410, buries its side chain in a pocket at the MIDAS Mg2+ ion in the β3 I domain. The surface at the MIDAS Mg2+ ion is not visible in this view, which is in contrast to the surface at the ADMIDAS Ca2+ ion (Fig. 2 b, purple), which is much more solvent exposed. The other deep pocket, on the αIIb side of the interface, is occupied by Lys-406 of the γC peptide (Fig. 2 b). This is the same pocket that is occupied by the Arg side chain of RGD peptides.

Fig. 3 compares the binding modality of the γC peptide (Fig. 3 a) to that of RGD-like peptides (Fig. 3, b–d). We first will describe the RGD peptide-binding modality and then return to γC and compare it with RGD. The A408R substitution yielding the lamprey-like RGD motif in the chimera peptide γC (Fig. 1 b) results in retention of αIIbβ3 antagonist activity (Kloczewiak et al., 1989). In the chimera γC peptide, the Arg-408 side chain extends directly into the αIIb-binding pocket (Fig. 3 b) and displaces Lys-406, which binds in this pocket in the γC peptide (Fig. 3 a).

In contrast to previous integrin structures with cyclized peptides (Xiong et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2004), the αIIbβ3 complexes with the chimera peptides show how an RGD peptide unconstrained by cyclization binds to an integrin and provide the best comparison with the γC peptide. The RGD tripeptide adopts a highly extended conformation across the integrin α/β intersubunit interface (Fig. 3 b). The Arg and Asp side chains extend in opposite directions, and the backbone in between is also extended. The conformation of the ligand backbone is stabilized as it crosses the interface between the αIIb and β3 subunits by two previously unremarked water molecules with strong density that are held in place by hydrogen bonds to the side chain of αIIb Asp-232 and backbone of β3 Ala-218 and that hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen of the Arg of RGD (Fig. 3 b). The Arg side chain of RGD forms a charged hydrogen bond to αIIb residue Asp-224 and also forms a hydrogen bond to an αIIb backbone carbonyl. The Asp side chain of RGD directly coordinates to the MIDAS Mg2+ cation and is further satisfied by three hydrogen bonds to the β3 backbone and one to the side chain of β3 Asn-215. The same geometry at the Asp is seen for all αIIbβ3 complexes, which are in the high affinity state (Fig. 3, a–c). Only one of the four Asp hydrogen bonds are seen at the Asp of the αvβ3 complex (Fig. 3 d) because it has a closed headpiece, and the two backbone nitrogens of the β1-α1 loop have not moved within hydrogen bonding distance; furthermore, the side chain of Asn-215 should probably be flipped.

By reducing the loss of peptide entropy upon binding, cyclization can increase affinity and is therefore widely adopted in drug development. Eptifibatide is a seven-residue L peptide that is cyclized with a disulfide bond, contains homoarginine-Gly-Asp in place of RGD, and is in clinical use for prevention of thrombosis (Fig. 3 c). Eptifibatide binds similarly to RGD, and the carbonyl oxygen of its homoarginine residue similarly hydrogen bonds to the waters held in place by αIIb Asp-232 (Fig. 3 c). However, cyclization pins back the homoarginine Cα and N atoms so that the Cγ atom of homoarginine is in a similar position to the Cβ atom of Arg, explaining the requirement for the one-carbon longer homoarginine side chain (Fig. 3, b and c).

Cilengetide, an αvβ3 antagonist, is a five-residue peptide that contains RGD, N-methyl-Val, and d-Phe (Fig. 3 d). The Arg of cilengitide forms a charged hydrogen bond to αv residue Asp-218. Cilengetide is cyclized through its peptide backbone in a considerably smaller ring than epitifibatide. Tight cyclization, which is important to prevent binding to αIIbβ3 (Scarborough and Gretler, 2000; Gottschalk and Kessler, 2002), pulls the Arg backbone back away from the αv subunit and helps place the Arg side chain further above the subunit than the Arg or homoarginine of αIIb ligands, as appropriate for the shallower αv binding pocket (Fig. 3 d).

The fibrinogen γC peptide complex with αIIbβ3 reveals that γC residue Lys-406 forms a charged hydrogen bond to αIIb residue Asp-224 (Fig. 3 a). Therefore, γC Lys-406 is functionally equivalent to the Arg of RGD (Fig. 3 b) and the homoarginine of eptifibatide (Fig. 3 c). Furthermore, the Ala-Gly-Asp moiety of γC has a conformation identical to that of Arg-Gly-Asp, and the carbonyl oxygen of Ala-408 hydrogen bonds to the two water molecules held in place by αIIb Asp-232 at the interface with the β3 subunit in a geometry identical to that seen for the Arg and homoarginine carbonyl oxygens of RGD and eptifibatide (Fig. 3, a–c). Indeed, the Cβ atoms of Ala-408 of γC and the Arg of RGD occupy identical positions (Fig. 3, a and b). The critical difference between the γC peptide– and RGD peptide–binding modalities is the backbone turn at γC residue Gln-407, which orients the N-terminal portion of the γC peptide into the groove formed by the long loops that connect αIIb β propeller blades 2 and 3 and blades 3 and 4 (Fig. 3 a). The backbone turn at γC Gln-407 enables the γC Lys-406 side chain to enter the αIIb binding pocket from a markedly different location than the Arg side chain of RGD (Fig. 3, a and b). The last few atoms of the Lys-406 side chain turn to approach αIIb Asp-224 from a similar direction as Arg (Fig. 3, a and b). A 15-fold loss of potency upon substitution of Lys-406 with Arg (Kloczewiak et al., 1989) is explicable by the inability of the planar guanido group of Arg to similarly turn. Hydrophobic αIIb residues Tyr-190, Leu-192, and Phe-231 line the pocket and contact the aliphatic portion of the γC Lys-406 side chain and the Ala-408 side chain. γC residues Gly-404, Ala-405, and Lys-406 fill the groove between adjacent β propeller blades and form backbone–backbone and backbone–side chain hydrogen bonds to αIIb residues Asp-159 and Ser-226 (Fig. 3 a). γC residues Gly-404 and Ala-405 also seal the binding pocket for the Lys-406 side chain, with γC residue Gly-404 forming a backbone hydrogen bond to the γC Lys-406 side chain.

ADMIDAS coordination

An important and unexpected observation is that the free carboxyl group of the γC C-terminal residue Val-411 coordinates the β3 I domain ADMIDAS calcium ion through an intermediate water molecule with strong density (Fig. 3 a). The contribution of this coordination to ligand binding is demonstrated by the finding that amidation of the α-carboxyl group decreases by sixfold the potency of γC peptides in inhibiting fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 (Kloczewiak et al., 1989). An identical ADMIDAS coordination is seen with the chimera QRGDV peptide (Fig. 3 b). The significance of this observation, the notable similarity in backbone positions of Val-411 of the γC and chimera peptides, and the equivalent residue in eptifibatide, Trp-5 (Fig. 3, a–c), is discussed in the next section.

Discussion

Specific recognition of the fibrinogen γC peptide by αIIbβ3

Our structures of γC peptides bound to αIIbβ3 reveal the interface that is biologically important for the binding of fibrinogen to activated integrin αIIbβ3 on platelets. This binding event, in turn, leads to cross-linking of platelets by fibrinogen and the formation of platelet plugs in hemostasis and thrombosis. Whereas Arg-Gly-Asp binds to eight different integrins, the fibrinogen γC peptide binds only to αIIbβ3.

Our γC peptide complex with αIIbβ3 reveals the basis for binding of platelet αIIbβ3 and endothelial αvβ3 to distinct sites in fibrinogen, enabling these integrins to have complementary rather than competitive functions in hemostasis (Fig. 1 a; Cheresh et al., 1989; Smith et al., 1990). The interface on the integrin α subunit occupied by the γC peptide is much larger than that occupied by RGD. γC residues Gly-404, Ala-405, Lys-406, and Ala-408 all interact with αIIb. In contrast, in the linear RGD chimera peptide, only Arg-408 binds to the αIIb subunit. This much more extensive interface with γC enables specific differences between αIIb and other integrin α subunits to be recognized as good contacts made by αIIb and clashes made by αv. The shallower and narrower binding site in the αv subunit precludes binding of the KQAGDV moiety using the αIIbβ3-bound conformation. For example, αv Ala-215 and Asp-218 would both clash with KQAGDV. These results show why the γC peptide does not bind to αv.

In contrast, RGD does bind to αIIbβ3, and, therefore, the selectivity of αIIbβ3 for the γC site over RGD in fibrinogen (Cheresh et al., 1989; Smith et al., 1990) must reflect a higher affinity for γC. Fibrinogen lacking the γC QAGDV pentapeptide fails to bind αIIbβ3 and results in bleeding disorders in mice (Farrell et al., 1992; Holmback et al., 1996). This emphasizes the absolutely critical role of the γC peptide in recognition by αIIbβ3; however, it does not mean that the γC peptide is responsible for all of αIIbβ3's affinity for fibrinogen. Indeed, αIIbβ3 has 100-fold higher affinity for fibrinogen than for the γC octapeptide (Kloczewiak et al., 1983, 1984). Mutagenesis studies show that the binding site on the αIIb β propeller domain includes, but is larger than, the γC octapeptide–binding site defined here (Kamata et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2004). The 10E5 Fab binds within this region of the αIIb β propeller that is important in fibrinogen binding and blocks binding of fibrinogen but not the octapeptide to αIIbβ3. Because the N terminus of the octapeptide extends toward the 10E5 Fab–binding site (Fig. 2), it is tempting to speculate that regions N terminal to the γC peptide, including well-folded γC module residues 144–392, also bind to αIIbβ3 and, together with the γC peptide, account for the higher biological affinity of αIIbβ3 for fibrinogen than for RGD peptides. Such other regions of the γC domain may also account for the retention of clot-retraction activity by fibrinogen deleted in the QAGDV pentapeptide (Holmback et al., 1996). Integrin binding or inhibition of clot retraction has been demonstrated using portions of γC N terminal to KQAGDV made in Escherichia coli (Medved et al., 1997; Yokoyama et al., 1999; Podolnikova et al., 2003); however; E. coli γC fragments also express integrin-binding sites that are not present on native fibrinogen (Akakura et al., 2006).

Multiple crystal structures of fibrinogen and its fragments show that γ chain residues 404–411 are disordered and that residues 393–403, when ordered, completely differ in conformation from one crystal lattice to another (Pratt et al., 1997; Spraggon et al., 1997; Yee et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2001; Kostelansky et al., 2002). Previous intense and creative efforts using carrier protein-driven crystallization (Donahue et al., 1994; Ware et al., 1999) failed to reveal the biologically relevant conformation of the γC peptide.

Our structures reveal the conformation that γC residues 404–411 adopt when bound to αIIbβ3. Although not inconsistent with the previous conclusion that QAGDV represents a minimal recognition unit in γC, our structure resolves the conundrum that QAGDV lacks a basic residue by demonstrating that Lys-406 fulfills a function similar to the Arg in RGD and that the KQAGD motif in γC occupies the same site as RGD. Residues Gly-404 and Ala-405 also appear to have an important role in sealing the binding pocket for Lys-406 in the αIIb groove.

In the absence of information on how the γC peptide binds αIIbβ3, development of the two currently approved small molecule αIIbβ3 therapeutics, tirofiban and eptifibatide, proceeded from RGD and barbourin, respectively (Scarborough and Gretler, 2000). Barbourin is a disintegrin with two highly unusual properties for a disintegrin: specificity for αIIbβ3 and KGD in place of the RGD motif (Scarborough et al., 1991). Lysine has a side chain with Cβ, Cγ, Cε, and Nζ atoms. The Arg side chain has Cβ, Cγ, and Cδ atoms and a guanido group with Nε, Nη1, Nη2, and Cζ atoms. The three N atoms of Arg give it versatility for hydrogen bonding. Although the Arg side chain readily forms charged hydrogen bonds through different guanido nitrogens to αIIb–Asp-224 in Fig. 3 b and αv–Asp-218 in Fig. 3 d, it is easy to imagine how a Lys in a similar position might better form a hydrogen bond to αIIb–Asp-224 than to αv–Asp-218. The final drug developed from barbourin, eptifabitide, has a homoarginine side chain in place of lysine (Fig. 3 c). This drug binds very similarly to RGD (Fig. 3 b) and quite differently from the γC peptide, in which the Lys side chain enters the αIIb binding pocket from a completely different direction (Fig. 3 a). Thus, drug design starting from KGD ironically resulted in an RGD-like antagonist with a binding modality very different from KQAGDV.

The γC complex structure provides new insights for the development of second generation integrin antagonists. Mimicking the novel route into the αIIb binding pocket adopted by the Lys of the KQAGDV motif should enable development of new classes of highly specific αIIbβ3 antithrombotics. Furthermore, mimicking the novel interaction with the ADMIDAS metal ion is attractive for improving the specificity and affinity of antagonists to a wide range of integrins.

The finding that the γC peptide–binding site completely overlaps the RGD peptide–binding site definitively resolves the long-standing controversy about whether these peptides compete for binding to the same site or bind to distinct sites (Lam et al., 1987; Santoro and Lawing, 1987; D'Souza et al., 1990; Hu et al., 1999; Bennett, 2001). Furthermore, our studies explain previous observations of photo–cross-linking of the γC dodecapeptide peptide to only the αIIb subunit and of an RGD hexapeptide to both the αIIb and β3 subunits, with cross-competition by RGD and γC peptides, respectively (Santoro and Lawing, 1987). Both peptides appeared to have the radiolabeled, photoactivatable reagent attached to their N-terminal α-amino groups. The exclusive labeling of αIIb by the reagent attached to γC His-400 is consistent with the position of Gly-404 in our structures in the αIIb β propeller groove and also with further extension in the N-terminal direction in this groove. In contrast, labeling of both the αIIb and β3 subunits by the reagent attached to the residue before the Arg of RGD is consistent with the position of the corresponding Gln-407 residue at the interface between the αIIb and β3 subunits in the chimera deca- and dodecamer structures.

A role for ADMIDAS in ligand binding

Previous crystal structures and mutation of MIDAS-coordinating residues have shown that the MIDAS metal ion has a direct role in ligand binding (Luo et al., 2007). In contrast, the ADMIDAS metal ion has been shown to have a regulatory role in ligand binding. During conversion from the low affinity, closed conformation to the high affinity, open conformation of the integrin headpiece, remodeling of the β1-α1 loop that coordinates to the ADMIDAS metal ion shifts the position of this metal ion by 3 Å (Xiao et al., 2004). Ca2+ and Mn2+ compete for binding to ADMIDAS, resulting in inhibition or stimulation of ligand binding, respectively (Chen et al., 2003). We note that physiologically and in the current structures, Ca2+ is present at ADMIDAS (Xiao et al., 2004) and that coordination is pentagonal bipyramidal, with seven oxygen ligands as typically seen for Ca2+. ADMIDAS mutations augment ligand binding by integrins α4β7 and αLβ2 (Chen et al., 2003, 2006) and, in contrast, inhibit ligand binding by αIIbβ3 and α5β1 (Bajt and Loftus, 1994; Mould et al., 2003). In this study, we find that in addition to its regulatory role, ADMIDAS can also directly contribute to ligand binding. The γC C-terminal COOH group coordinates the ADMIDAS Ca2+ ion through water with strong electron density. The importance of this interaction is demonstrated by the sixfold loss in inhibitory potency of γC peptides when the C terminus is amidated.

It should be noted that the amidation experiment only demonstrates that coordination to a charged carboxyl oxygen is stronger than to a carbonyl oxygen. Both types of oxygens form direct and indirect water-mediated coordinations to Ca2+ (Harding, 2001). Therefore, the importance of ADMIDAS coordination may extend beyond fibrinogen to include ligands with RGD sequences that are not followed by the C-terminal residue. In eptifibatide, the Arg-Gly-Asp-Trp-Pro-Cys sequence places a Pro in the same position as in the Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro sequence of fibronectin; this Pro, the bulky Trp, and cyclization place constraints on backbone conformation. Nonetheless, the Trp carbonyl oxygen in eptifibatide is in a position very similar to that of one of the two α-carboxyl oxygens of the γC and chimera peptide Val-411 residues (Fig. 3, a–c). In the absence of the constraints in the cyclic peptide, this carbonyl could move slightly and form a water-mediated coordination to the ADMIDAS similarly to the γC and RGD chimera peptide Val-411 carboxyl group. Water with weak density may be in a position to make this coordination in the eptifibatide complex structure (Fig. 3 c). Furthermore, the carbonyl oxygen of the amidated Cys two residues after the Trp forms a water-mediated coordination to the ADMIDAS (Fig. 3 c). Water-mediated ADMIDAS coordination to RGD ligands provides a plausible explanation for the finding that mutation of ADMIDAS-coordinating residues inhibits RGD-dependent binding of α5β1 to fibronectin (Mould et al., 2003) and binding of αIIbβ3 to the peptide GRGDSP (Bajt and Loftus, 1994), although ADMIDAS mutations also appear to favor the inactive conformation of α5β1 (Mould et al., 2003). We propose that the stimulatory effect of ADMIDAS mutations on ligand binding by integrins that do not recognize RGD, α4β7 (Chen et al., 2003), and αLβ2 (Chen et al., 2006) reflects the regulatory role of ADMIDAS and that the inhibitory effect of ADMIDAS mutations on ligand binding by integrins that recognize RGD (or KQAGDV), αIIbβ3 (Bajt and Loftus, 1994), and α5β1 (Mould et al., 2003) reflects a direct role of ADMIDAS in ligand recognition, in addition to a regulatory role. This proposal requires testing with further integrin–ligand crystal structures.

Evolution of the KQAGDV motif from an RGD motif in fibrinogen

Fibrinogen first evolved in vertebrates (Jiang and Doolittle, 2003). The significance of ADMIDAS coordination by the C-terminal carboxyl group of the fibrinogen γ subunit is emphasized by the fact that in vertebrates, the position of the C-terminal carboxyl group relative to the penultimate Asp residue has been invariant for the last 450 million years (Fig. 1 b; Strong et al., 1985). Thus, the interaction with ADMIDAS of the C-terminal carboxyl group first evolved in jawless vertebrates in the context of an RGD motif and was maintained when warm-blooded vertebrates evolved the KQ(A/V)GD motif and bony fishes evolved the KQFGG(I/L)GD motif in place of the RGD motif (Fig. 1 b). Our structures also explain why in fibrinogen the residue that takes the place of the Arg in RGD is conserved as a hydrophobic residue and suggest that the three-residue insertion in bony fishes can be accommodated as a longer turn between the Lys and this hydrophobic residue.

The presence of an RGD motif in both lamprey and frog and the presence of a KQ(A/V)GDX motif in warm-blooded vertebrates and a KQFGG(I/L)GDI motif in bony fishes (Fig. 1 b) raises the possibility that evolution from the recognition of Arg to Lys occurred more than once. A plausible stepping stone in this evolutionary process is provided by the function of Lys in fibrinogen cross-linking. In lamprey as well as in higher vertebrates, fibrinogen is cross-linked within the γC peptide by the factor XIIIa transglutaminase (Strong et al., 1985). Lys-406 is cross-linked to Gln-398 or Gln-399 in human, and the Lys N-terminal to the RGD in lamprey is cross-linked to one of the more N-terminal Gln residues (Strong et al., 1985). Xenopus laevis appears similar to lamprey, with Lys and Gln residues N-terminal to the RGD. In contrast, humans, other warm-blooded vertebrates, and bony fishes resemble one another by all having the lysine that is known (human) or implicated (other species) in binding to αIIbβ3 as the same lysine that is known (human) or implicated (other species) in cross-linking. In γC peptides with RGD motifs, the Lys that functions in cross-linking could later have evolved a second function in specific recognition of a platelet integrin, providing an evolutionary stepping stone from RGD-based recognition of fibrinogen by multiple integrins to Lys-based recognition of fibrinogen by a specific integrin on platelets or thrombocytes. Whether there is any more significance to the dual function of Lys-406 in human fibrinogen γ is unclear. However, there would be little, if any, competition between these two functions of Lys-406 because fibrinogen binding to platelets occurs much earlier in the clotting cascade than fibrin formation, and the fibrinogen that contributes to fibrin formation is in great excess over that bound to platelet integrin αIIbβ3.

Materials and methods

The γC dodecapeptide was obtained from the American Peptide Co., and other peptides were synthesized and verified by mass spectrometry by the biopolymer facility at the Department of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Crystals of the αIIbβ3 headpiece bound to 10E5 Fab in 11% polyethylene glycol 3350, 0.7 M magnesium acetate, and 0.1 M cacodylate, pH 6.5 (Xiao et al., 2004), were cryoprotected with a solution containing 15% polyethylene glycol 3350, 0.7 M magnesium acetate, and 0.1 M imidazole, pH 6.5, plus 5% step increases of glycerol concentration to a final 20% glycerol, and then 50 μM of synthetic peptides was added in the final cocktail. Crystals were soaked for 4 d at 4°C before freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected with beamline 19ID (Advanced Photon Source) and processed with program suite HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). As there is little difference in the dimensions of the unit cell compared with nonpeptide-soaked crystals, the previously determined structure of the αIIbβ3 headpiece complexed with 10E5 Fab (1TXV; 2.7 Å) was directly subjected to rigid body refinement program CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) using the diffraction data. Electron density calculated using phases from the refined structure clearly showed the presence of the peptides. The peptide structures were built with program O and subjected to iterative cycles of model rebuilding in O and refinement using CNS (version 1.1) as previously described (Xiao et al., 2004).

Subsequent rebuilding with Coot and refinement with REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997) resulted in structures with unusually low Rfree (Tables I and II), which may be attributed to multiple factors. Regions for rebuilding were identified using multiple verification tools in Coot to detect structural defects supplemented with improved definition of Ramachandran outliers, clashes, and improbable rotamers using MolProbity (Davis et al., 2007). Rebuilding first focused on the higher resolution 2.4- and 2.6-Å γC chimera deca- and dodecapeptide structures. These structures were refined in parallel so that rebuilding could focus on problems identified by verification tools or discrepancies between the model and electron density that were shared between two independent datasets. One of the shared discrepancies was a clash at αIIb residue 282 accompanied by a lack of density for the putative Ala-282 Cβ atom; checking of the nucleotide sequence used for αIIb expression and RefSeq entry gi88758615 reveals Gly at this position compared with Ala in UniProt entry P08514. Rebuilding of the Fab was aided by comparison with multiple high resolution VH, CHI, VL, and CL domains that were found by BlastP search of the protein database and were individually superimposed on the 10E5 Fab. In the four γC and chimera γC peptide complexes, Fab residue Asn-157 in the light chain appears to have largely undergone deamidation with conversion to isoaspartic acid. This residue is in an Asn-Gly sequence, the sequence known to be most susceptible to deamidation (Aswad et al., 2000), and previous protein chemistry on the mouse light chain peptide containing this sequence revealed heterogeneity, suggesting chemical rearrangement (Svasti and Milstein, 1972). The previously determined headpiece structures (Table II) did not show evidence for isoaspartic acid, which is consistent with deamidation during prolonged storage of the Fab before preparation of the more recent crystals (Table I). Although isoaspartic acid has been built in one case (Esposito et al., 2000), we did not do so because of the difficulty of implementing the correct restraints for an isopeptide bond in the peptide backbone and the mixture of products, including l- and d-aspartic acid, that result from deamidation (Aswad et al., 2000). The Xpleo server was used to guide rebuilding of several loops that were difficult to build manually (van den Bedem et al., 2005). Although not built in our previous headpiece structures (Xiao et al., 2004), I-EGF domain 1 residues 436–461 are clearly present, although they are less well ordered than other domains. The last disulfide-bonded loop of I-EGF1, residues 462–472, either was disordered or was removed by carboxypeptidase A, which stopped at Arg-461. Arg is known to be resistant to digestion by carboxypeptidase A (Ambler, 1967). Compared with our previous headpiece structures (Xiao et al., 2004), carbohydrate linkages were corrected to those known to occur in high mannose N-linked glycans; three cis-prolines were added, and one was removed. TLS refinement in REFMAC5 used groups determined with the TLS Motion Determination server (Painter and Merritt, 2006) and contributed a 2–3% drop in Rfree.

The γC dodecamer and decamer structures and the five previously deposited αIIbβ3 headpiece 10E5 Fab complex structures (Xiao et al., 2004) were then rerefined starting with the ligands in the previous models and the headpiece-Fab moiety from the refined chimera γC decamer complex 2.4-Å structure described in Table I. Ligand topology and parameter cif files were created by the PRODRG2 server (Schuttelkopf and van Aalten, 2004). The cacodylate and eptifibatide ligands are unchanged. Use of correct chirality and flip of the peptide bond relative to the thienothiophene moiety in the L-739758 ligand and rotations around the sulfonamide N atoms in L-739758 and tirofiban result in better fits to density and hydrogen bonding to αIIbβ3. The Rfree of the five previously deposited structures is decreased by 2.1–5.1%. αIIb residue 123 appears to be a true Ramachandran outlier; other outliers are in regions of poor density. All coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the PDB. The unusually low Rfree of the deposited structures is consistent with quality assessment by the MolProbity server (Davis et al., 2007), which returns MolProbity scores in the 100th percentile for all nine structures (where 100th percentile is the best) compared with other deposited structures at similar resolutions.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL48675 to T.A. Springer.

T. Xiao's present address is National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ADMIDAS, adjacent to MIDAS; I-EGF, integrin EGF-like; MIDAS, metal ion–dependent adhesion site.

References

- Akakura, N., C. Hoogland, Y.K. Takada, J. Saegusa, X. Ye, F.T. Liu, A.T. Cheung, and Y. Takada. 2006. The COOH-terminal globular domain of fibrinogen gamma chain suppresses angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 66:9691–9697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambler, R.P. 1967. Carboxypeptidases A and B. Methods Enzymol. 11:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Aswad, D.W., M.V. Paranandi, and B.T. Schurter. 2000. Isoaspartate in peptides and proteins: formation, significance, and analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 21:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt, M.L., and J.C. Loftus. 1994. Mutation of a ligand binding domain of β3 integrin: integral role of oxygenated residues in αIIbß3 (GPIIb-IIIa) receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 269:20913–20919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J.S. 2001. Platelet-fibrinogen interactions. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 936:340–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T., P.D. Adams, G.M. Clore, W.L. DeLano, P. Gros, R.W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J.-S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N.S. Pannu, et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., A. Salas, and T.A. Springer. 2003. Bistable regulation of integrin adhesiveness by a bipolar metal ion cluster. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., W. Yang, M. Kim, C.V. Carman, and T.A. Springer. 2006. Regulation of outside-in signaling by the β2 I domain of integrin αLβ2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:13062–13067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheresh, D.A., S.A. Berliner, V. Vicente, and Z.M. Ruggeri. 1989. Recognition of distinct adhesive sites on fibrinogen by related integrins on platelets and endothelial cells. Cell. 58:945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cierniewski, C.S., T. Byzova, M. Papierak, T.A. Haas, J. Niewiarowska, L. Zhang, M. Cieslak, and E.F. Plow. 1999. Peptide ligands can bind to distinct sites in integrin αIIbß3 and elicit different functional responses. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16923–16932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza, S.E., M.H. Ginsberg, T.A. Burke, and E.F. Plow. 1990. The ligand binding site of the platelet integrin receptor GPIIb-IIIa is proximal to the second calcium binding domain of its alpha subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 265:3440–3446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, I.W., A. Leaver-Fay, V.B. Chen, J.N. Block, G.J. Kapral, X. Wang, L.W. Murray, W.B. Arendall III, J. Snoeyink, J.S. Richardson, and D.C. Richardson. 2007. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W375–W383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, J.P., H. Patel, W.F. Anderson, and J. Hawiger. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of the platelet integrin recognition segment of the fibrinogen γ chain obtained by carrier protein-driven crystallization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:12178–12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, R.F., and J.M. Kollman. 2006. Natively unfolded regions of the vertebrate fibrinogen molecule. Proteins. 63:391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, L., L. Vitagliano, F. Sica, G. Sorrentino, A. Zagari, and L. Mazzarella. 2000. The ultrahigh resolution crystal structure of ribonuclease A containing an isoaspartyl residue: hydration and sterochemical analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 297:713–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, D.H., P. Thiagarajan, D.W. Chung, and E.W. Davie. 1992. Role of fibrinogen α and γ chain sites in platelet aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:10729–10732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, K.E., and H. Kessler. 2002. The structures of integrins and integrin-ligand complexes: implications for drug design and signal transduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41:3767–3774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, M.M. 2001. Geometry of metal-ligand interactions in proteins. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 57:401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawiger, J. 1995. Adhesive ends of fibrinogen and its antiadhesive peptides: the end of a sage? Semin. Hematol. 32:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmback, K., M.J. Danton, T.T. Suh, C.C. Daugherty, and J.L. Degen. 1996. Impaired platelet aggregation and sustained bleeding in mice lacking the fibrinogen motif bound by integrin alpha IIb beta 3. EMBO J. 15:5760–5771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.D., C.A. White, S. Panzer-Knodle, J.D. Page, N. Nicholson, and J.W. Smith. 1999. A new model of dual interacting ligand binding sites in integrin αIIβ3. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4633–4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., and R.F. Doolittle. 2003. The evolution of vertebrate blood coagulation as viewed from a comparison of puffer fish and sea squirt genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:7527–7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata, T., K.K. Tieu, T.A. Springer, and Y. Takada. 2001. Amino acid residues in the αIIb subunit that are critical for ligand binding to integrin αIIbβ3 are clustered in the β- propeller model. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44275–44283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloczewiak, M., S. Timmons, and J. Hawiger. 1983. Recognition site for the platelet receptor is present on the 15-residue carboxy-terminal fragment of the gamma chain of human fibrinogen and is not involved in the fibrin polymerization reaction. Thromb. Res. 29:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloczewiak, M., S. Timmons, T.J. Lukas, and J. Hawiger. 1984. Platelet receptor recognition site on human fibrinogen synthesis and structure-function relationship of peptides corresponding to the carboxy-terminal segment of the gamma chain. Biochemistry. 23:1767–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloczewiak, M., S. Timmons, M.A. Bednarek, M. Sakon, and J. Hawiger. 1989. Platelet receptor recognition domain on the γ chain of human fibrinogen and its synthetic peptide analogues. Biochemistry. 28:2915–2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostelansky, M.S., L. Betts, O.V. Gorkun, and S.T. Lord. 2002. 2.8 A crystal structures of recombinant fibrinogen fragment D with and without two peptide ligands: GHRP binding to the “b” site disrupts its nearby calcium-binding site. Biochemistry. 41:12124–12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.C.-T., E.F. Plow, M.A. Smith, A. Andrieux, J.-J. Ryckwaert, G. Marguerie, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1987. Evidence that Arginyl-Glycyl-Aspartate peptides and fibrinogen γ chain peptides share a common binding site on platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 262:947–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, S.C., I.W. Davis, W.B. Arendall, P.I. de Bakker, J.M. Word, M.G. Prisant, J.S. Richardson, and D.C. Richardson. 2003. Structure validation by Cα geometry: phi, psi and Cβ deviation. Proteins. 50:437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B.-H., C.V. Carman, and T.A. Springer. 2007. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25:619–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, K.H., and F. Fan. 1996. Integrin receptor GPIIb/IIIa bound state conformation of the fibrinogen γ-chain C-terminal peptide 400-411: NMR and transfer NOE studies. Biochemistry. 35:4434–4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medved, L., S. Litvinovich, T. Ugarova, Y. Matsuka, and K. Ingham. 1997. Domain structure and functional activity of the recombinant human fibrinogen gamma-module (gamma148-411). Biochemistry. 36:4685–4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould, A.P., S.J. Barton, J.A. Askari, S.E. Craig, and M.J. Humphries. 2003. Role of ADMIDAS cation-binding site in ligand recognition by integrin α5β1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51622–51629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov, G.N., A.A. Vagin, and E.J. Dodson. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z., and W. Minor. 1997. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter, J., and E.A. Merritt. 2006. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62:439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolnikova, N.P., V.P. Yakubenko, G.L. Volkov, E.F. Plow, and T.P. Ugarova. 2003. Identification of a novel binding site for platelet integrins aIIbb3 (GPIIbIIIa) and a5b1 in the gC-domain of fibrinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 278:32251–32258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, K.P., H.C. Cote, D.W. Chung, R.E. Stenkamp, and E.W. Davie. 1997. The primary fibrin polymerization pocket: three-dimensional structure of a 30-kDa C-terminal gamma chain fragment complexed with the peptide Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:7176–7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, S.A., and W.J. Lawing Jr. 1987. Competition for related but non-identical binding sites on the glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex by peptides derived from platelet adhesive proteins. Cell. 48:867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough, R.M., and D.D. Gretler. 2000. Platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa antagonists as prototypical integrin blockers: novel parenteral and potential oral antithrombotic agents. J. Med. Chem. 43:3453–3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough, R.M., J.W. Rose, M.A. Hsu, D.R. Phillips, V.A. Fried, A.M. Campbell, L. Nannizzi, and I.F. Charo. 1991. Barbourin. A GPIIb-IIIa-specific integrin antagonist from the venom of Sistrurus m. barbouri. J. Biol. Chem. 266:9359–9362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuttelkopf, A.W., and D.M. van Aalten. 2004. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60:1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.W., Z.M. Ruggeri, T.J. Kunicki, and D.A. Cheresh. 1990. Interaction of integrins αvβ3 and glycoprotein IIb-IIIa with fibrinogen: differential peptide recognition accounts for distinct binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 265:12267–12271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spraggon, G., S.J. Everse, and R.F. Doolittle. 1997. Crystal structures of fragment D from human fibrinogen and its crosslinked counterpart from fibrin. Nature. 389:455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong, D.D., M. Moore, B.A. Cottrell, V.L. Bohonus, M. Pontes, B. Evans, M. Riley, and R.F. Doolittle. 1985. Lamprey fibrinogen γ chain: cloning, cDNA sequencing, and general characterization. Biochemistry. 24:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svasti, J., and C. Milstein. 1972. The complete amino acid sequence of a mouse kappa light chain. Biochem. J. 128:427–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bedem, H., I. Lotan, J.C. Latombe, and A.M. Deacon. 2005. Real-space protein-model completion: an inverse-kinematics approach. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61:2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware, S., J.P. Donahue, J. Hawiger, and W.F. Anderson. 1999. Structure of the fibrinogen γ-chain integrin binding and factor XIIIa cross-linking sites obtained through carrier protein driven crystallization. Protein Sci. 8:2663–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T., J. Takagi, J.-h. Wang, B.S. Coller, and T.A. Springer. 2004. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding of fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 432:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J.P., T. Stehle, R. Zhang, A. Joachimiak, M. Frech, S.L. Goodman, and M.A. Arnaout. 2002. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin αVβ3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science. 296:151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z., J.M. Kollman, L. Pandi, and R.F. Doolittle. 2001. Crystal structure of native chicken fibrinogen at 2.7 A resolution. Biochemistry. 40:12515–12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee, V.C., K.P. Pratt, H.C. Cote, I.L. Trong, D.W. Chung, E.W. Davie, R.E. Stenkamp, and D.C. Teller. 1997. Crystal structure of a 30 kDa C-terminal fragment from the gamma chain of human fibrinogen. Structure. 5:125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, K., X.P. Zhang, L. Medved, and Y. Takada. 1999. Specific binding of integrin alpha v beta 3 to the fibrinogen gamma and alpha E chain C-terminal domains. Biochemistry. 38:5872–5877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]