Abstract

During the 1990s, the New York Police Department (NYPD) instituted a policy of arresting and detaining people for minor offenses that occur in public as part of their quality-of-life (hereafter QOL) policing initiative. The number of NYPD arrests for smoking marijuana in public view (MPV) increased from 3,000 in 1994 to over 50,000 in 2000, and have been about 30,000 in the mid 2000s. Most of these arrestees (84%) have been minority; blacks have been 2.7 more likely and Hispanics 1.8 times more likely to be detained than whites for an MPV arrest. Minorities have been most likely to receive more severe dispositions, even controlling for demographics and prior arrest histories.

This paper examines the pros and cons of the current policy; this is compared with possible alternatives including the following: arrest and issue a desk appearance ticket (DAT); issue a non-criminal citation (violation); street warnings; and tolerate public marijuana smoking. The authors recommend that the NYPD change to issuing DATs on a routine basis. Drug policy reformers might wish to further pursue changing statutes regarding smoking marijuana in public view into a violation (noncriminal) or encourage the wider use of street warnings. Any of these policy changes would help reduce the disproportionate burden on minorities associated with the current arrest and detention policy. These policies could help maintain civic norms against smoking marijuana in public.

Keywords: Marijuana, arrests, ethnic disparities, policing policy, quality-of-life, criminal sanctions

Introduction

In general, policing policy needs to be responsive to a variety of factors including new and innovative policing strategies, advances in technology, shifting public concerns, shifts in offending behaviors and the historical impact of prevailing policies. In this manner, policing policy integrates globally best practices within a local context in accord with prevailing criminal activity, policy history, and current values. This paper examines the New York City Police Department (NYPD) current response to public marijuana use and analyzes the pros and cons of potential alternative policies.

In a previous paper, Johnson et al. (2006d) described how the NYPD substantially shifted its policy towards public marijuana use several times in the past. The current policy is to arrest and detain the majority of persons caught smoking marijuana in public settings. This policy has been in place since the mid-1990s. By 2000, arrests for smoking Marijuana in Public View (abbreviated MPV arrests) had become the most common misdemeanor charge among adult arrestees (Golub, Johnson and Dunlap, 2006, 2007; corresponding figures for juvenile MPV arrests are not available but would be large). The more than 50,000 MPV arrests that year constituted about 15% of all adult arrests. Most of these arrestees (84%) were black or Hispanic. In light of this massive use of police resources, its heavy impact on younger persons in minority communities, and the continuation of the current policy for more than a decade, we suggest that New York City (NYC) and the NYPD should strongly consider changing its MPV policy. This paper examines the following alternative policy options for dealing with public marijuana use: 1) Arrest and Detain (the current policy); 2) Arrest and Issue a Desk Appearance Ticket (DAT); 3) Non-Criminal Citation (Violation); 4) Street Warning, and 5) Tolerate Public Marijuana Smoking (No offense).

The remainder of this paper provides a brief history of policing marijuana use in NYC, discusses the major stakeholders associated with this policy, evaluates the potential for each of the policy options, and presents our preliminary recommendation.

New York City's History of Marijuana Law Enforcement

Marijuana was first prohibited in 1914 in New York City, in 1927 by New York State, and the USA by the Federal Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 (Bonnie and Whitebread 1970). Marijuana was classified as a narcotic. From 1937-74, marijuana offenses were treated as harshly as heroin and cocaine offenses in New York State (NYS 2005). In 1975, NYS created a separate section of its legal code to deal with marijuana offenses (NY PL221)—in which personal possession of small amounts of marijuana in private settings was decriminalized; the sale and possession of larger amounts of marijuana remained criminal offenses.

From 1980-1994, the NYPD policy generally discouraged police officers from making arrests for marijuana use or sales. A companion article describes this era in considerable detail:

During this period, enforcement against marijuana users or sellers was among the “lowest” priorities of the NYPD—in part because violent and property crime soared, homicides increased, and sales of heroin and cocaine expanded greatly (Blumstein and Wallman 2006; Johnson, et al. 2006c). Massive drug enforcement effort was primarily directed at heroin and especially at crack sellers during 1985-1999. Police officers had the discretion to stop marijuana smokers or sellers and discard their marijuana but not initiate the arrest process….to avoid possible corruption of (and payoffs to) police officers….

In the 1970s-80s, the proliferation of drug sellers in the City effectively shifted the “effective” standards—so that the citizenry accepted the presence of hundreds of marijuana sellers and ignored marijuana smoking in public locations…. Virtually every street in low income neighborhoods and every city park had one to several persons selling “loose joints” ($1) and “nickel” ($5) or “dime” ($10) bags of marijuana (and often other illegal drugs)…. Most non-using citizens were offered an opportunity to purchase marijuana by one or several sellers. Marijuana smoking and sales in public places was widely tolerated by nonusers and public policy makers—the latter had more serious problems (crack, homicides, violence, disorder) to address. (Johnson et al 2006d: 62-65)

Take Back the Streets

In 1992, Rudolph Giuliani was elected Mayor after making numerous campaign promises to “take back the streets” from drug dealers and to improve the quality of life in the city. Under Mayor Giuliani and his successor Mayor Michael Bloomberg and their police commissioners (Bratton, Safir, Kerik, and Kelly), the NYPD initiated numerous “tough on crime” programs and policies. (For historical reviews see Bratton with Knobler, 1998; Guiliani with Kurson, 2002; Kelling and Coles, 1996; Kelling and Sousa, 2001; Maple with Mitchell, 2000; Rosenfeld, Fornango, and Baumer 2005; Silverman, 1999.) These major policing initiatives greatly impacted the numerous marijuana users and sellers in public settings. Four of these initiatives resulted in frequent police contacts and many arrests of marijuana smokers and sellers in public locations: 1) suppression of street-level drug sellers; 2) nuisance abatement, 3) QOL policing, 4) streamlining many procedures so the arrest-to-arraignment process involved fewer hours of police time (see details in Rosenfeld, Fornango, Baumer, 2005; Johnson et al., 2006d).

This paper focuses on QOL policing, an initiative that seeks to improve the overall quality of life by aggressively enforcing laws (especially by arrest) against minor offenses that occur in public and that may be deemed offensive to the general population. This approach has also been referred to as order maintenance policing, zero-tolerance policing (because it focuses on enforcement of even the most minor offenses), and fixing broken windows (under the theory that an unkempt community invites crime). As part of QOL policing, the NYPD targeted the use of marijuana in public view (hereafter MPV). An extensive scientific literature documents the widespread use and heavy use of marijuana and blunts (marijuana in cigar shells) in the United States (Golub 2006; Golub, Johnson, Dunlap 2005) and elsewhere.

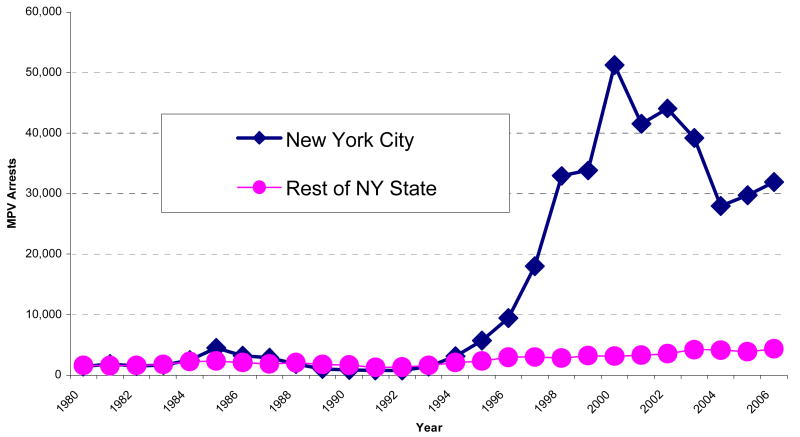

Based on an analysis of national arrest statistics, King and Mauer (2006) concluded that during the 1990s the U.S. war on drugs had transformed into a war on marijuana (also see Reuter, Hirshfield, Davies 2001). This transformation certainly was occurring in NYC—but not in the rest of New York State. Figure 1 shows that less than 5000 MPV arrests annually are recorded outside of NYC, as was the case in NYC before 1996. But QOL policing increased the number of NYPD arrests for smoking marijuana in public view (MPV) from 3,000 in 1994 to over 50,000 in 2000, to about 30,000 in the mid 2000s. During 1980-1994, MPV constituted 1 percent or less of all NYPD arrests but increased to 15% by 2000 and has been about 10% in the mid-2000s. By 2000, the number of marijuana arrests in NYC rivaled the number of controlled substance arrests.

Figure 1. Annual Arrests for Marijuana in Public View in NY State.

Source: Computed from New York State arrest databases by Andrew Golub 2007.

Law enforcement and public health authorities regularly support criminal statutes that define arrest and sanctions for marijuana possession and sale—arguing that such sanctions are necessary to express societal disapproval and to prevent marijuana use and heavy use. In large measure, these claims about the effectiveness of criminal sanctions are mainly a restatement of the moral positions and societal disapproval that are continuously advanced by public officials.

The extensive scientific literature about marijuana is almost entirely framed within a public health (and not criminal justice) framework—and each issue is extensively documented and debated. A huge literature documents cannabis' connection to withdrawal syndrome, dependence, mental health problems (especially schizophrenia), amotivational syndrome, poor performance while driving, as well as damage to the body's cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, immunosuppression, and psychiatric functioning (reviewed by Hall and Pacula 2003; also see Brown 1998, Dunlap et al. 2005, 2006; Earleywine 2007; Golub and Johnson 2001, 2002, 2004; Sabet 2007; Zimmer and Morgan 1997). An alternative literature suggests that cannabis may have medicinal value for addressing a wide range of various medical diseases, though smoked product may be harmful, the active ingredients in cannabis, most notably THC/dronabinol may have medicinal value (Grinspoon and Bakalar 1997; Institute of Medicine 1999). This large and convoluted literature frames the issue of marijuana policy in general but for this paper represents numerous side issues that distract from an appropriate focus upon policing policy in New York City regarding public marijuana use.

A New York Times article appearing in 1998 reported that, “Arrests on marijuana charges have jumped to a record number this year, driven by the Giuliani administration's ‘zero tolerance’ approach that has police officers pursuing anyone found possessing, selling or smoking even small amounts of marijuana” (Flynn, 1998). As of 2006, Mayor Bloomberg continued a focus on QOL policing and on MPV (New York Times, 2006a) and was expanding the police force (New York Times 2006b). The majority of marijuana arrestees have been charged with criminal possession of marijuana in the fifth degree as per the following statute (NYS, 2005):

NY PL221.10 Criminal possession of marihuana in the fifth degree (MPV) —

A person is guilty of criminal possession of marihuana in the fifth degree when he knowingly and unlawfully possesses:

marihuana in a public place, as defined in section 240.00 of this chapter, and such marihuana is burning or open to public view; or

one or more preparations, compounds, mixtures or substances containing marihuana and the preparations, compounds, mixtures or substances are of an aggregate weight of more than twenty-five grams.

Criminal possession of marihuana in the fifth degree is a class B misdemeanor.

In the 2000s, ‘loose joints’ ($1) and even nickel bags ($5) of marijuana are rarely available from street sellers and only in low income neighborhoods. In more affluent communities such as Manhattan south of 96th street, street marijuana sellers are rare and dime bags ($10) are uncommon. Rather, many middle class marijuana purchasers buy $50 “cubes” of designer marijuana which arrive via a delivery service (Sifaneck et al., 2006). Johnson et al. (2006d) noted that marijuana use and sales are much less visible in the present period almost certainly as a result of such policing (also see Johnson, et al. 2006c; Ream et al. 2006):

Blunt and marijuana users are keenly aware that police are arresting and processing persons for marijuana smoking and possession of a joint/blunt. Few users report reducing their marijuana consumption due to the possibility of police contacts…. Marijuana use rates in the city appear close to or below the national averages and probably haven't changed greatly in the past decade.

As a major outcome of active enforcement, concealment efforts by persons using joints and blunts in public settings means that their public consumption is less visible and observable to the ordinary citizen than was common in NYC in the early 1990s. They appear to passersby to be complying with marijuana-related civic norms—even when not doing so.

Marijuana sellers are highly aware that police are arresting persons for marijuana sales; many have been stopped and/or arrested (often for possession rather than sales). They maintain a much lower profile in public locations than in the 1980s. They rarely approach or aggressively hawk their wares to unknown passersby. The more organized marijuana sellers prefer to develop delivery services and charge high minimum delivery prices. (Johnson et al 2006d).

Other scholars have questioned how much (if any) of the NYC crime drop was due to policing initiatives, which of the initiatives were most effective (e.g., gun laws versus more QOL policing), and whether the crime drop may have resulted from other factors such as the decline of the crack epidemic and its violent drug markets (Blumstein and Wallman, 2006; Johnson et al., 2006b,c; Rosenfeld, Fornango, and Baumer 2005). During the 1990s, marijuana supplanted crack as the drug-of-choice among youths, especially in the inner city (Golub, 2006; Golub and Johnson, 2001).

Proactive police enforcement (Golub et al 2002, 2003) during the last half of the 1990s and 2000s appears to have largely re-established widespread observance by consumers of civic norms against marijuana smoking and sales in public locations. As used here, civic norms are commonly accepted guides (usually prohibitions against) some type of behavior(s) in public settings. In large measure, civic norms rely heavily upon voluntary compliance and informal social norms shared by the vast majority within the community (Johnson et al 2006b,c, 2007). Often civic norms are converted into laws or regulations that are typically established by some regulatory agency and usually enforced by officials of those agencies. The main sanctions usually involve a ticket or summons issued at the spot of the offense with the violator subsequently paying a fine. Even when the civic norm may be opposed by those impacted, the majority of those engaged in the behaviors will comply with those restrictions and pay the fines imposed. Marijuana smoking in public view is one behavior defined by a penal statute as a criminal offense, but is more typically viewed as a civic norm by citizens, marijuana users, and even by law enforcement officials. Indeed, the central question poised in this article: Should marijuana smoking in public be treated as a “crime” or as a “violation?”

Race/Ethnicity Disparities

Many public officials and police analysts have credited the policing effort with improving the quality of life in NYC, increasing tourism, and reducing both minor and more serious crimes including murder (see references to historical reviews in previous paragraph). Serious crime (FBI Part I and II) crimes have declined in absolute numbers, so that NYC is now one of the safest major cities.

But a dark side of this proactive policing policy has been the large and continuing ethnic disparities in who gets arrested and officially sanctioned. Critics have alleged that the NYPD's aggressive law enforcement in the 1990s inappropriately targeted blacks and Hispanics (Amnesty International, 1996; Curtis, 1998; Eterno, 2001; Harcourt, 2001; McArdle and Erzen, 2001; Spitzer, 1999). Numerous studies (Becket et al. 2005a,b; Coker 2003; Flynn 1999) document the vast over-representation of black males and Hispanic males among arrested and incarcerated populations. Even samples of general populations record much higher stops by police of African-American and Hispanics than whites for a wide range of offenses (Weitzer and Tuch 2006).

MPV arrests are unpleasant for those charged, can result in an arrest record, and can be potentially viewed as harassing and unfair. Most importantly, the time spent during the process of arraignment (arrest, holding cells, detention, appearance in court) becomes the primary punishment for such minor offenses (Feeley 1992; Packer 1968). Flynn (1998) described the typical criminal justice experience:

Most of those arrested [for marijuana possession offenses] today are held for arraignment and can spend 16 to 36 hours in custody before being released, in sharp contrast to the past, when those arrested on low-level possession charges were often given a summons and not taken into custody.… First offenders…are eligible for a probation program known as adjournment contemplating dismissal in which charges are dismissed if a defendant stays out of trouble for a set period of time…. ‘We call that doing your jail time up front,’ said Tony Elitcher, a staff lawyer with the Legal Aid Society' criminal defense division. ‘You are doing your sentence before you ever get in front of the judge.’

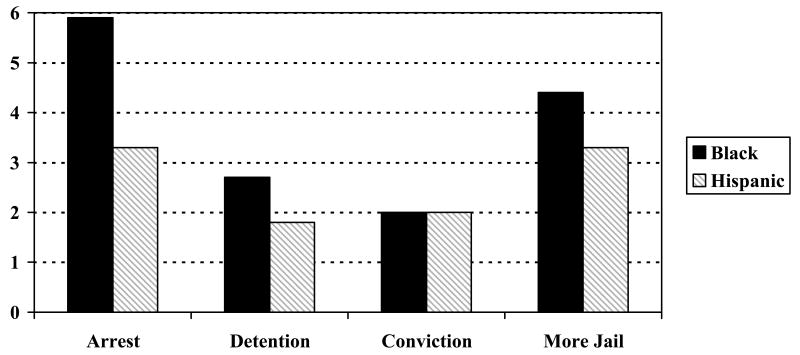

Golub, Johnson, and Dunlap (2007) documented that the NYPD's current policy for marijuana arrest resulted in disparities by race/ethnicity at each stage of the criminal justice system from arrest, to detention, conviction and sanctions. These findings are summarized in Figure 1 which examines disparity ratios for treatment of blacks compared to whites and for Hispanics compared to whites. The race disparity ratio at arrest was calculated according to the following formula:

An analogous ratio was calculated for Hispanic MPV arrestees. These ratios provide a rough estimate of the risk for arrest among black (and Hispanic) adult residents in contrast to the risk for white residents. A ratio of 1.0 would suggest that blacks (or Hispanics) received similar criminal justice treatment as their white counterparts. A ratio greater than one indicates the extent that they were treated more harshly.

In 2000, Black adults were nearly six times (5.9) more likely to be arrested for MPV than were whites based on their percentage of the residential population. Hispanics were more than three times (3.3) as likely as whites (see Figure 2). These ratios, however, are somewhat controversial. Spitzer (1999) reported a similar ratio with regard to the NYPD “Stop-and-Frisk” program noting that 85% of all subjects searched under the program were black or Hispanic in contrast to their 50% of the residential population. The NYPD countered that it would be more appropriate to compare the search rate with the 89% rate at which victims of violent crimes described their perpetrators as black or Hispanic (Flynn, 1999; NYPD, 1999). Using a similar argument, the fact that 84% of MPV arrestees were black or Hispanic is not inconsistent with the fact that most arrestees (82%) in 2000 were black or Hispanic. Thus, the counterargument could be that blacks and Hispanics were disproportionately more likely to sustain arrests for a wide variety of offenses including MPV.

Figure 2. Race/Ethnicity Disparity Ratios (as compared to whites) in Criminal Justice Experiences among Adult MPV Arrestees in NYC in 2000-03 (computed from Golub et al 2007).

Arrest = ratio of estimated risk of MPV arrest for black (or Hispanic) vs. white adult NYC residents, based on 2000 census

Detention = ratio of estimated risk of detention among black (or Hispanic) vs. white adult males arrested for MPV in Manhattan 2000-2003

Conviction = ratio of percent of black (or Hispanic) vs. white adult MPV arrestees convicted

More Jail = ratio of black (or Hispanic) vs. white adult MPV arrestees sentenced to additional time in jail

Golub, Johnson, and Dunlap (2007) estimated the disparity ratios for the rate of pre-arraignment detention among MPV arrestees using data on the race composition of MPV arrestees selected by the ADAM program from 2000 to 2003. This analysis was limited to adult male arrestees in Manhattan (excluding females and the five outer boroughs), because the ADAM-Manhattan program was designed to obtain a representative sample of this population. Black MPV arrestees were 2.7 times and Hispanic MPV arrestees were 1.8 times more likely to be detained than their white counterparts using the following formula:

Using similar calculations, Golub, Johnson and Dunlap (2007) estimated that Black and Hispanic MPV arrestees were twice as likely to be convicted as their white counterparts. Black MPV arrestees were 4.4 times more likely and Hispanic MPV arrestees were 3.3 times more likely to be sentenced to additional jail time as their white counterparts. These disparity ratios in MPV sanctioning persisted even after controlling for the extent of criminal histories.

Ostensibly, the increase in MPV arrests was part of NYC's focus on QOL policing. Golub, Johnson and Dunlap (2006) analyzed the geographic distribution of MPV arrests and its change over time from 1992 to 2003. They found that in the early 1990s that most MPV arrests were recorded in the lower half of Manhattan (NYC's business and cultural center) and by the police in the transit division (responsible for subways and buses). This distribution is consistent with the goal of QOL policing, to reduce the offensive behavior of marijuana smoking in highly public locations. However, since the mid-1990s and into the 2000s, most MPV arrests have been recorded in higher poverty, minority communities outside the lower Manhattan area and by the NYPD's policing of low-income housing projects. This geographical shift suggests that smoking marijuana in public may have been brought under control in highly public locations and that the continued emphasis on MPV arrest has shifted to lower-income communities.

In one small-scale study, some evidence suggest that black marijuana smokers in NYC were more likely to be stopped by the police despite the fact that they were more careful to take precautions against arrest (Ream et al. 2006, 2007; Johnson et al. 2006c). A survey of 513 marijuana smokers from NYC found that more black marijuana smokers (42%) reported that they never smoked in public than their white counterparts (20%). Hispanic respondents (33%) fell between the two. However, the interpretation of findings from this NYC survey are limited because the study did not identify the extent that blacks were more likely to smoke marijuana at all and because the representativeness of the sample of marijuana smokers surveyed has not been established.

In a Supreme Court Review on the topic of racial injustice, Coker (2003, pp. 862-3) pointedly argued:

The political discourse regarding racial disparities in the criminal justice system has largely focused on intentional discrimination committed by actors motivated by racial bias. A focus on bad actors and racial motives obscures the bigger picture of a system that systematically and disproportionately burdens communities of color with the excesses of law enforcement without many of the benefits. One such way would be to assess the overall impact of criminal justice policies on the well-being of communities of color, particularly African American communities who are so frequently targeted by law enforcement efforts.

We concur with Coker's (2003) perspective that race/ethnicity disparities in the criminal justice system need to be systematically addressed (also see Weitzer and Tuch 2006). Ending or substantially reducing disparities associated with MPV arrests would increase the equitability of justice in NYC (Golub, Johnson, and Dunlap 2006).

A Policy Analysis Framework

This paper provides a framework for analyzing potential changes in NYC's policy regarding dealing with people smoking marijuana in public. The issue is to reduce race/ethnicity disparities while maintaining widespread compliance with civic norms against the public use and sale of marijuana. To this end, we employ a standard analytic framework that focuses on three distinct perspectives on policy analysis (Allison, 1971): the rational, political, and organizational perspectives. Allison (1971) suggests that these domains operate in parallel and interact. The rational perspective asks the question of what is the best policy option. This approach has been most completely realized in cost benefit analysis. Recommendations derived from such rational analysis need to be tempered by political considerations. Perhaps the most cost effective measures may not be acceptable to various stakeholders with their own concerns. Any “best” solution (if one even exists) ultimately represents a tradeoff among competing stakeholders and interests (Kleiman 1989; MacCoun and Reuter 2001).

The following analysis indicates the relative preference for each of the policy options according to the various key stakeholders' concern including NYC residents and visitors (a joint interest), poor minority communities, marijuana smokers, and the NYC criminal justice system. These categories represent ideal types. Some individuals will have multiple affiliations and concerns. For instance, the NYPD is included to represent their interest in minimal disruption to their current standard operating practices according to Allison's organizational perspective. Additionally, however, many police officers will be interested in maintaining civic norms (as will city residents and visitors), others may be greatly concerned with race/ethnic disparities (based on connections with poor minority communities). The remainder of this section describes each stakeholder's primary concern regarding marijuana policy. The subsequent section elaborates on the advantages and disadvantages of each policy option.

NYC residents and visitors

NYC is a major center for business, residence and leisure activities. In support of this activity, residents and visitors desire a safe experience within an attractive locale. NYC experienced a Renaissance during the 1990s. Crime and most drug-related crime are way down. Graffiti has been mostly eliminated, parks and green areas have been rehabilitated. Real estate is booming, and gentrification is occurring in many NYC low income neighborhoods. In this regard, NYC has achieved a higher overall quality of life for most New Yorkers, at least with regard to low crime and low disorder. (Note: this analysis does not consider affordability or availability of jobs for the less educated.) Almost completely lacking in the news reports and political life of NYC, however, is any discussion of marijuana smoking in public locations (Johnson et al 2006d). A major unknown is how bothered the general public and nonusers may be by the smell of marijuana smoke, or by observations of young adults smoking marijuana in public settings.

Poor minority communities

Citizens residing in poor, predominately minority communities appear to be of two minds regarding proactive policing. On the one hand, many black and Hispanic leaders campaign to get more police resources devoted to “stopping crime” in their communities—which often leads to more police stops and arrests of minority residents of that community. In this regard, their concerns are similar to other NYC residents and visitors. On the other hand, many minority citizens also experience that police stop them, search them, and release them for no good reason—except “walking or standing while black.” Often, these citizens perceive and resent that blacks and Hispanics are singled out, treated much differently, and are more frequently harassed by police. Marijuana use is only one of the many things minorities are “hassled” about.

Marijuana smokers

Marijuana smokers, especially those who frequently use in public settings currently risk being stopped, arrested, detained, and sanctioned. Clearly, they would prefer to smoke in peace, whereever and whenever they desire. Whether such public marijuana smokers deserve to be officially treated as criminals, experience criminal sanctions, and be officially labeled as criminals, is the central policy question. Organizations lobbying for marijuana decriminalization and legalization (e.g., the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA), Marijuana Policy Project, and Student for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP) generally support the interests of the marijuana smokers in public policy debates. On the other hand, other stakeholders are likely to place much less value on marijuana smokers' concerns and may not even recognize such concerns as legitimate. Accordingly, the interests of marijuana smokers may not hold much sway in selecting an option for responding to marijuana smoking in public.

NYPD and NYC Criminal Justice System

The NYPD and allied criminal justice organizations are included in this analysis as the agencies with responsibility for enforcing the law. Their concern is to maintain smooth operations. According to Allison's organizational perspective, they would wish to develop a policy not too different from the current standard operating procedures and therefore straightforward to implement. These criminal justice groups have a central concern associated with suppressing serious crime. It has been argued that while processing QOL arrestees that the NYPD gains information helpful in solving more serious offenses. Specifically the NYPD collects digital photographs of the arrestee's face and digitized photos of handprints, both of which can be rapidly searched and retrieved by computer software (far faster than paper-based photos and fingerprints).

Taxpayers

Cost is always an important public policy concern to those that eventually have to pay the bill, the taxpayers. The current MPV policy (option 1 below) is likely very expensive in terms of police time for seeking out and arresting marijuana smokers, transportation to, supervision in detention, and arraignment—all to achieve a vague outcome (fewer persons smoking marijuana in public settings). Police time and court expenses run at least several hundred dollars for an average MPV arrest and detention (Option 1). In a more comprehensive cost analysis, Miron (2003) estimated that Massachusetts could save approximately $24 million if marijuana was decriminalized—a figure that might be 10 fold greater in NYC. However, estimating any cost savings is complex. In the short-term, police, incarceration and court costs are largely fixed. Even if marijuana were legalized (option 5) or warnings issued (option 4), and 30,000 MPV arrests no longer occurred, it is unlikely that 10% fewer police officers or court personnel in NYC would be let go or not hired. Accordingly, it might take years before any possible cost savings were fully realized. More likely, personnel freed from processing MPV arrestees would be available for other law enforcement initiatives. Thus, the cost savings would be realized through more extensive funding of other programs. It could also be argued that imposing fines for DATs (option 3 below) would bring in some revenue. However, in practice this seems unlikely as many of the poor arrestees would not be able or willing to pay any fines imposed.

Analysis of Policy Options

We identify several policy options for reducing ethnic disparities and the costs associated with arrests for marijuana smoking in public view. Options 1, 2, and 4 are within the purview and discretion of the police chief and Mayor of New York City. The third and fifth options may necessitate a change in criminal codes by the New York State Legislature. The following include several options that would change the current policy, with a goal of reducing ethnic disparities (and other inequities) documented in the literature review. In defining the policy options below, the authors are NOT recommending each policy option briefly described here. Rather the pros and cons of each policy option are weighed below.

This analysis compares the advantages and disadvantages of the NYPD's current marijuana arrest policy (option 1--arrest and detain) with four successively less punitive options designed to reduce the race/ethnic disparity.1 The five policy options for public marijuana use include: 1) Arrest and Detain (the current NYPD policy); 2) Arrest and Issue a Desk Appearance Ticket (DAT); 3) Issue a Non-Criminal Citation (Violation); 4) Street Warnings (discard marijuana and warn violator); and 5) Tolerate Public Marijuana Smoking.

Option 1: Arrest and Detain (Current NYPD Policy)

This policy has been in effect for approximately a decade (since 1995) in NYC, because marijuana smoking is included as one of many different offenses included under the city's QOL enforcement practices. Under the powers granted to the police under NY PL221.10, police can and do arrest persons when they smell marijuana being smoked, often only a small amount of marijuana is seized, perhaps a partial joint or two. These arrestees are brought to central detention cells, and held for 16-36 hours before an appearance at arraignment. Sometimes several additional persons who were not smoking marijuana may be arrested because someone in a group was. Following NYPD arrest procedures, persons are formally arrested, taken to a precinct house, hand printed, entered into a computer database (“booked”), and checked for warrants or current criminal records. Then the person is held in the precinct “lockup” for 1-10 hours, transported to the central arraignment, and often waits 10-20 additional hours in large detention cells with 30 to over 200 other persons arrested on a variety of charges. When the MPV arrestee appears before the Arraignment Court judge, the MPV charge will almost always be disposed—typically outright “dismissed,” or “adjourned in contemplation of dismissal.” (Johnson et al, 2006d).

Advantages

A wide variety of reasons have been given to justify maintaining the current NYC arrest-and-detain policy for MPV arrestees. 1) Marijuana use is illegal. 2) Enforcement of this law indicates the importance of this civic norm and expresses the moral disapproval by the larger society of smoking of marijuana in public locations (even when that same behavior can be legally conducted in private locations without fear of arrest or criminal sanction). 3) Such criminal laws help protect the public health, since marijuana use may lead to dependence and harmful consequences to the smoker's health (via dependence, respiratory and heart diseases, cancer, etc.). 4) Reducing the public visibility of marijuana smoking and sales contributed to the large quality of life improvements in NYC.

In addition, the NYPD has several rationales for QOL enforcement and detention that are not directly related to marijuana. 5) Detained persons can be interviewed by detectives investigating other crimes in their community for possible leads to solving other crimes. 6) Detailed identification data is collected for every arrestee that may assist in solving future crimes (possibly committed by that arrestee). 7) The average police officer can easily locate and make an “easy arrest” for MPV, thus enhancing their arrest and production statistics. In defending QOL policing, the NYPD often refers to the case of John Roister who was hand printed following an arrest for fare evasion in 1995 (Bratton with Knobler 1998; Guiliani with Kurson 2002). Roister had no other criminal history record. In 1996, fingerprints found at the scene of a murder on Park Ave were matched with his handprint. Police located Roister, he confessed to that murder and two other widely separated homicides, and is now serving a life sentence.2

Disadvantages

As reviewed above, our analysis argues that the ethnic disparities in detention and imposition of more serious sanctions for MPV constitute a very important reason to significantly alter the current arrest-and-detain policy. We argue below that the civic norms against marijuana smoking in public locations can likely be maintained by other policies and thus express the continuing moral disapproval of the majority. The threat and actual arrest for MPV appear to have no or little measurable impact upon marijuana consumption patterns of those arrested. Police will continue to arrest and prosecute those hawking or selling marijuana in public settings.

During arrest proceedings, extensive personal identifying information is systematically collected and maintained in sophisticated computer systems. Although most MPV dispositions are “sealed” (and are not supposed to be provided on “rap sheets” of subsequent arrests)—those detained are now permanently identified (by photos and handprints) as having had an official “brush” with the law (Johnson et al 2006d). That information can and will be held against them in the future. Criminal history information is also provided to private companies who retrieve such data for future use (NY Times 2006c). For example, a person arrested, detained, and given a “time served” disposition (guilty) for an MPV arrest could possibly be denied federal funds to support college attendance. Or an employer conducting a record search, might learn about that record and deny the person a job—without their knowledge. Acquiring an official arrest record, or adding even a minor charge to an existing criminal history, constitutes an important secondary reason for changing current MPV policy. Marijuana users, especially low income blacks and Hispanics, would be the stakeholders having the most to gain if option one policy were changed.

Option 2: [DAT] Arrest and Desk Appearance Ticket

This option was most commonly used by the NYC Police Department in the 1970s and 1980s; it is still used, but less often during QOL enforcement in the 2000s. If a person is stopped for smoking marijuana in a public place, the officer arrests the person but issues a desk appearance ticket [DAT] (see Johnson et al 2006d: 85-87). This requires the arrestee to appear at a criminal arraignment court approximately 1 month after the arrest. Typically the MPV charge is either dismissed, Adjudicated in Contemplation Of Dismissal (ACOD), or the person pays a fine. In this regard, a DAT is like a speeding ticket, although the defendant appears in a criminal as opposed to traffic court. The important difference (from option one) is that the MPV arrestee is not transported to and held in detention cells for up to 24 hours or more. But they will appear before the same arraignment court judge (as detained persons) about 30 days later—and will typically have an outcome of dismissed, ACOD or a fine. This option would dramatically decrease the number of persons, especially minorities, who would be detained for 24 hours or more. Indeed, at the current time, DATs are often issued to persons who have good identification, so many middle class and whites arrested for MPV may disproportionately receive DATs.

Advantages

The NYPD could issue DATs for MPV arrests by improving upon a previous policy (see Johnson et al., 2006d). Under this policy option, the police officer could stop the marijuana smoker, obtain identification, and conduct a standard record check to identify any outstanding warrants or determine that an arrestee is on probation or parole. The minority of MPV arrestees with warrants or probation/parole status would continue to be detained as under option one. The great majority of MPV arrestees with no outstanding concerns, however, could be given a DAT in the street or at the precinct and be expected to appear before the arraignment judge a month later. This change would help eliminate the large volume of black and Hispanics MPV arrestees who experience detention and are “doing their jail time up front” before ever getting in front of the judge (Flynn 1998). Of course, substantial ethnic disparities may persist among the minority of MPV arrestees detained (not given DATs), mainly because blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to have existing warrants, probation, or parole status.

In the mid-1990s, police and prosecutors objected to these DATs, which they mockingly referred to as “disappearance tickets.” Almost half the arrestees receiving DATs in the 1990s never appeared in court (Maple with Mitchell 1999). Since 1995, however, the NYPD (and most police departments) have implemented a wide range of technological improvements based upon computerized record keeping and offender management that have advanced police ability to track all forms of crimes, violations and offenders. This technology could greatly enhance compliance with DATs. The NYPD now uses electronic equipment at the precinct house to obtain a digital handprint of every arrestee, as opposed to the older fingerprinting procedure. This new technology would allow the NYPD to quickly compare each arrestee's handprint to an electronic database of handprints maintained by the department. In addition, the NYPD warrant squad may be more effective at locating persons who do not appear in court (and have outstanding warrants). Such “no shows” could be subsequently arrested for both the original MPV charge and failure to appear in court. Even if the DAT resulted in a “no show” who was never re-arrested, the desired deterrent effect may have been achieved (the person is not re-arrested for public marijuana smoking). Further, the court would issue a warrant, so that if the person is arrested on any other charge, they would face more serious penalties for an outstanding warrant, than if fined for the marijuana possession offense. Moreover, almost all the police costs associated with transporting, detaining, and arraigning the individual would be saved.

Disadvantages

The DAT policy would reduce the burden of detention for MPV arrest disproportionately impacting blacks and Hispanics, although it does not reduce the fuller impact of sustaining an arrest. Another problem is that NYC has a long history of chronic misdemeanor offenders who routinely ignore DATs. Currently, persons who would ignore DATS are punished via 12-36 hours of detention (as are a majority who would appear if given a DAT). Some would argue that persons arrested for MPV deserve to be punished by detention regardless of whether they would appear if released with a DAT and regardless of their final disposition in court. Proponents of this “tough on crime” perspective would also argue that virtually all MPV arrestees are actually guilty of having “broken the law” (PL221.10), knowingly flouting the civic norm, and deserve to be punished by detention. Although police managers at the NYPD appears committed to option one policy for most arrestees, the NYPD could implement this option two with little difficulty and possibly reduce their expenses somewhat.

Option 3 [Violation]: Issue a Non-Criminal Citation

The legal basis for arresting and detaining persons for smoking marijuana in a public setting rests on the first numbered phrase in NY Penal Code 221.10 (cited in full above), which specifies possession of “marihuana in a public place…and such marihuana is burning or open to public view.” If this phrase were removed, then smoking marijuana in public would be subject to NY Penal Code 221.05, whenever less than 25 grams is involved (see below).

NY PL221.05 Unlawful Possession of Marijuana (violation) —

A person is guilty of unlawful possession of marihuana when he knowingly and unlawfully possesses marihuana. Unlawful possession of marihuana is a violation punishable only by a fine of not more than one hundred dollars.3

Persons charged with a violation are generally issued a C-summons (like a traffic ticket) and if convicted will generally pay a fine. This option would help eliminate ethnic disparities in MPV arrest and processing by creating a ticket for marijuana smoking in public, which would only be answerable at a later date and time. Defendants would not be formally arrested for a criminal charge, handprinted, and detained for varying time periods; the most serious disposition under this option would be a fine. Moreover, persons would not acquire an “official” criminal record for this violation.

Advantages

If political agreement could be reached, the NYS legislature could make marijuana smoking in a public location a violation rather than a misdemeanor. If the proposed modification were adopted, then persons smoking marijuana in public would no longer be subject to arrest, but would be subject to non-criminal penalties such as fines and graduated fines for repeat offenders. Reducing the harshness associated with an MPV intervention would not violate the legal principle that the punishment should be in proportion to the seriousness of the crime. Rather, persons caught smoking marijuana in public would be treated similarly to those drinking alcohol in public.

Reducing the severity of the charge from a misdemeanor to a violation would benefit numerous blacks and Hispanics who are disproportionately affected by arrest and detention for public marijuana smoking. They would not acquire an official criminal history (if a first arrest), nor have it recorded as a criminal arrest (as a misdemeanor) in NYS criminal history files. The vast majority contacted for MPV would be released at the location of their initial contact with the police officer. This policy option would reserve criminal sanctions and a criminal record for those people who commit more serious offenses. Persons selling marijuana to undercover officers or persons possessing 25 grams or more of marijuana (enough to make about 25 joints or blunts) would still be subject to arrest and detention under PL221.10, but very few persons have that much marijuana in their possession at the time of arrest. This policy change would need to gain the support of political leaders in the NYS legislature to change the wording of this penal law.

Disadvantages

The police and “tough on crime” constituencies might predict that many persons, especially regular marijuana smokers, will more willingly smoke marijuana in public settings and eventually erode the civic norm against public use. Furthermore, public smokers might tend to ignore a summons issued for a violation and fail to appear in court or pay fines. Some marijuana sellers caught possessing (but not selling) small amounts of marijuana (under 25 grams) might treat the C-summons and fines as merely a “cost of doing business.” They might continue selling but limit the amounts they hold at any one time to less than 25 grams. In this regard, the “tough on crime” advocates might forecast that both marijuana users and nonusers would interpret the violation status as “approving” of public marijuana use. Another limitation of this less punitive policy would be that the NYPD would no longer detain persons nor be able to conduct a search for an arrestee's prior criminal record nor to interview them about other possible crimes in the neighborhood.

Option 4 [Warn]: Street Warning (Stop, Warn, Destroy, No Record)

Police could potentially maintain the civic norms against smoking marijuana in public without imposing sanctions. When a police officer observes someone smoking marijuana in a public setting, he or she could issue a Street Warning (May et al 2007) to the person that this is a violation of law, seize the marijuana and throw it down a drain (or otherwise discard it), but ultimately release the smoker at the end of that contact. This police-civilian contact would create no written or official record of arrest or summons (also no booking, detention, or disposition). The primary punishment would be the loss of the user's marijuana and possibly the embarrassment of an official rebuke. While never a formal policy in many jurisdictions, this practice may be a common discretionary option follow by police officers in the streets--especially when the police procedures and court requirements are complicated and time-consuming (May et al 2002). In the late 1980s, NYC police officers had much discretion to ignore or warn marijuana smokers and were generally encouraged to do so. At that time, arrests for MPV were not encouraged by the NYPD precinct commanders (McCabe 2005, cited in Johnson et al. 2006d).

Advantages

This policy option, if used widely, would nearly eliminate formal arrest, detention, and the imposition of various criminal sanctions with such police contacts, and dramatically reduce ethnic disparities associated with current MPV policy. Further marijuana smokers would not acquire official criminal records, nor add another minor (MPV) offense to their existing records. Marijuana users and many minorities would be very pleased if this alternative were widely implemented.

Disadvantages

From the “tough-on-crime” perspective, this policy would allow the smoker off “scott free” after violating a civic norm and further allow them to potentially disrespect a police officer. This “soft-on-crime” policy could potentially shift the effective civic norm leading to an increase in smoking of marijuana in public settings.

Option 5 [No Offense]: Tolerate Public Marijuana Use

NYC could implement a policy of tolerating the public use of marijuana by either a non-enforcement practice or by changing statutes. The NYPD could simply decide (or be instructed) to not enforce the law against smoking marijuana in public. This option is very similar to policies which encourage police departments to make marijuana enforcement their “lowest priority,” and to effectively ignore marijuana smoking in public settings. (Such policies appear to be in effect in Oakland, Baltimore, Ann Arbor, and some other cities. Also see the British experience reviewed below.) This policy option could leave the legal statutes intact, but would have the effect of not imposing formal arrest or the other criminal sanctions. Taking this one step further, the NYS legislature could consider removing penal statutes (221.10) (or legalizing) personal use of marijuana in small quantities in public settings.

Advantages

This policy would effectively eliminate ethnic disparities in arrests for marijuana smoking or possession of small amounts. This policy option would have the effect of making marijuana smoking in public places equivalent to smoking a cigarette or a cigar in a public place. This alternative would be especially popular among marijuana consumers and among minority populations, but might be offensive to the large population of nonusers and nonsmokers. Since NYC has passed regulations which prohibit tobacco smoking in office buildings and businesses, most tobacco smokers now go outdoors (into public settings) to smoke; adding marijuana smoke into such settings would appear to be a minor addition to the numerous tobacco smokers.

Disadvantages

This policy could encourage consumers to openly smoke marijuana in public settings—just as cigarette smokers do currently. Law enforcement would have almost no role in marijuana control (except when larger amounts, over 25 grams, or marijuana sales occur). Tough-on-crime advocates might argue that the policy would also encourage the uninitiated to begin using marijuana, and to approve of the blatant use of marijuana in public settings. While the “official” civic norm would no longer prohibit public marijuana use, public policies could promote the “informal” observance of this civic norm (Johnson et al. 2007), in much the same way that tobacco smokers widely observe the indoor smoking ban.

The British Experience

A brief presentation of a recent change in British cannabis policy is relevant here. In the 1990s, cannabis (both marijuana and hashish are commonly available in Britain) was a Class B drug (British laws are similar, but have different titles, than in the USA). The police were expected to arrest persons possessing small amounts of cannabis; thereafter the offenders would either be given a formal police warning, called a “caution”; or else they would be charged and sentenced by the court, especially if they were repeat offenders. Where convicted, they would typically receive a small fine, but very occasionally were given a short jail sentence. Whether offenders are cautioned by the police or sentenced by the court, the offense is included in the person's criminal record. This “cautioning” British policy was closest to the Non-Criminal Violation (Option 3) policy above. Of note, the British police often issued street warnings (option 4) in practice.

Recently, Cannabis law was changed in Great Britain. During 2000-2003, there was much public debate about cannabis policy, following publication of an independent report recommending reclassification issued by the (British) Police Foundation (2000). The Labour Government was originally against reclassification, but after advice from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, it eventually opted for cannabis' reclassification as a Class C drug. This reclassification was debated in Parliament, and was adopted after a 360 to 160 vote. The policy change came into effect in January 2004 (Warburton, May, Hough 2005).

Reformers had argued for reclassification because this would reduce the maximum sentence for possession to two years, making it a non-arrestable offense. However, before reclassification, the Government had made a further change to the legislation, to ensure that possession remained an arrestable offense regardless of any changes in its classification (See Warburton May, Hough 2005). More confusingly still, they then encouraged police chiefs to issue guidance to their officers not to arrest offenders for possession, but to issue street warnings for possession.

As of 2007, the British policy was that cannabis is a Class C drug and that possession remains an arrestable offense, although the maximum penalty has been lowered. However, police officers encountering persons in possession of small amounts of cannabis are authorized to confiscate the drug and warn the smoker not to do it again. They are encouraged and expected to issue Street Warnings except for repeat offenders or where there are other aggravating circumstances. Thus, many fewer cannabis offenders are now arrested, and street warnings are substituting both for cautions and for court proceedings (May et al., 2007). Police jurisdictions continue to have different policies (some arrest and caution, others mainly issue street warnings).

Very few British police contacts for cannabis actually occur in wide open public settings where casual passersby would notice someone. May et al (2007) document that less than 20 percent of police cannabis arrests involved such general patrolling. Rather, most cannabis-related arrests occurred due to proactive policing activities (undercover officers observing or doing buy and busts, car stops, bike patrols, etc.) which locate cannabis users consuming in public but in semi-secluded locations. Further, those arrested for cannabis use rarely have other charges at the time of their arrest.

While challenges continue to be raised, the initial findings tend to refute assertions commonly made by “tough on crime” constituencies. Certainly, no major explosion in cannabis use has occurred, nor has public smoking or selling become commonplace. Indeed, a recently released British Crime Survey (Home Office 2006) documents that self-reported cannabis use has continued a modest decline which had begun well before this policy change occurred. Among British 16-24 year olds about 27% reported past-year cannabis use in 1996-2002, declining somewhat to 25% in 2003-04, and declining more significantly to 21% in 2005-06 (Home Office 2006, p. 51). While the rates of lifetime use remained quite stable (just over 40%), past month cannabis use also showed declines--from 18% in 1998 to 16% in 2003-04 and to 13% in 2005-06. These data clearly demonstrate that a pre-existing downward trend in cannabis use in Britain has not been altered by the new policy.

Most importantly, no upward swing in cannabis use is evident in Britain despite this apparent “softening” in police procedures.

The fact that cannabis use has continued to fall to its lowest level in nearly 10 years is further evidence that the decision to reclassify the drug to Class C was sound,” said Martin Barnes, chief executive of the charity DrugScope. “Some warned that the change would lead to an increase in cannabis use, yet the reverse has happened, possibly because there is more awareness of the possible harms.”

If the above conclusion is generally correct, the choice among the five policy options is nearly irrelevant—if the goal is to change social patterns of cannabis use. Moreover, any choice among the five policy options quickly becomes reduced to “haggling” and “symbolic political rhetoric” over what police officers do after contacting someone for cannabis use or possession in public places.

General vs. Proactive policing

Lost in debates over policy is the operational issue of how police locate persons in public who are in possession of or smoking marijuana. General enforcement refers to when an officer in the course of normal patrolling smells marijuana or observes a person consuming marijuana in an open setting. Or when the officer checks out a report that someone is smoking marijuana in public. In such situations, the officer stops the offender(s), seizes the cannabis product, and arrests them. In both situations, the marijuana use and smoker is typically located in a public place (street, park, etc.) where nonuser citizen might smell or observe the offender.

By contrast, proactive enforcement involves police (often in squads) employing tactics (observing buyers, stop and search, car stops, investigating other crimes, etc.) designed to locate offenders who are concealing their behaviors from citizenry (and police). Probably, the vast majority of MPV arrests result from proactive tactics. During drug squad tactics, suspected offender(s) are stopped and searched for guns, drugs, and other contraband. While the majority of such searches result in nothing illegal, many suspects are found to possess cannabis (even though marijuana is not being smoked nor visible to the public). Or police go into park corners, alleyways, stairwells or other locations that are well concealed from passersby but locate persons possessing or smoking marijuana. In NYC, the police conduct random searches of public stairwells and passageways in public housing were youths and young adults are encountered smoking blunts. Such proactive enforcement practices result in the arrest of one to several persons who are making consistent efforts to comply with the civic norm by finding remote locations or concealing their marijuana possession. Indeed, the dramatic differences in MPV arrests in New York City compared with upstate New York is probably due to different policing policies. Lower number of MPV arrests in upstate New York (∼4,000 annually) likely result from police arrests occurring during general enforcement, while the seven-fold greater number of MPV arrests (∼30,000) are the result of many different proactive policing tactics in New York City in the mid-2000s [see Figure 1].

Recommendation

At this time, the authors suggest two policies, with each recommendation aimed at different constituencies. We recommend to NYPD and court personnel a shift to Arrest and DAT (Option 2). But we also recommend that advocates for drug law reform seek to change penal statutes to convert marijuana use in a public into a violation (Option 3) or pressure public officials to ignore MPV (Option 4).

Police and Courts

The authors recognize that the NYPD is highly satisfied with its QOL enforcement and has weathered serious criticism and demonstrations against its tactics which result in substantial ethnic disparities in arrests and dispositions. Moreover, political pressure for changing policing policy appears very weak and is routinely ignored—so the NYPD and courts are highly likely to continue option 1 (arrest and detain) for most MPV offenders for the foreseeable future.

But option 2 (arrest with DAT) is a very viable alternative that is most likely to accomplish the twin goals set forth in the introduction (reduce ethnic disparities and maintain public order). Option 2 is the least likely to generate much controversy, among stakeholders and constituencies with “tough-on-crime” and “liberalizer” positions.4 This policy could be quietly tested by the NYPD Commissioner and staff without involving other constituencies. The NYPD could easily implement the policy, and possibly reduce the police and court processing costs somewhat. This policy change could be kept out of the political debate about whether marijuana possession should be “legal,” “decriminalized,” or “tough (soft) on crime.” The authors hypothesize that this policy would generate about the same major outcomes, that is, a similar number of MPV arrestees given DATs, yet with no major increase in public marijuana smoking.

We further recommend that the NYPD return its focus on MPV enforcement to NYC's most highly public locations. In a companion analyses, Golub et al. (2006) observed a dramatic shift in the geographic distribution of MPV arrests from 1992 to 2003. In the early 1990s, most MPV arrests were recorded in the lower half of Manhattan (NYC's business and cultural center) and on the city's subways and buses. This distribution is consistent with the goal of QOL policing, to reduce the offensive behavior of marijuana smoking in highly public locations. However, since the mid-1990s and into the 2000s, most MPV arrests appear to have resulted from proactive patrols instituted in high poverty, minority communities outside the lower Manhattan area and by the NYPD's policing of low-income housing projects. By returning its focus to the most public locations, the city could likely experience a dramatic decline in the number of MPV arrests without any observable impact on civic norms. Because most of the MPV arrestees have been black or Hispanic, this policy modification would greatly benefit these populations and somewhat reduce the number of persons with criminal records for MPV. This policy could be designed to systematically reduce or lessen ethnic disparities in NYC in criminal justice procedures, as recommended by Coker (2003).

The impact of this policy should be monitored to ensure that the race/ethnicity disparity is reduced and that civic norms to not smoke marijuana in public are maintained. In the future, NYC might find that it occasionally needs to return to the more severe Arrest and Detain policy to maintain the civic norms (hopefully only for short periods of time and limited to only a few highly public locations). Alternatively, NYC might find that it is able to maintain civic norms through even less punitive approaches such as the Non-Criminal Violation or Street Warning policies. Lastly, it may be eventually determined that NYC residents and visitors are not particularly offended by smoking marijuana in public, that this policy does not seriously diminish the quality of life in the city, and that such an option enhances the quality of life for a minority. In which case, simply tolerating public marijuana use (perhaps limited to some less public areas or restricted from the most public areas) might become an appropriate policy alternative.

At the current time, the authors stand by a recommendation toward an incremental shift from the current Arrest and Detain (option 1) to the Arrest and DAT (option 2) policy as potentially improving the overall satisfaction across NYC stakeholders without disrupting the current social arrangements too much. This Arrest and DAT policy would greatly reduce the inconveniences experienced by the thousands who are now detained, somewhat diminish ethnic disparities in MPV, and reduce an individual's criminal history.

Drug Policy Reformers

Several organizations and activists in New York City now represent the interests of marijuana smokers and users—but have not been well organized and politically active in changing marijuana laws and policies in New York City; their counterparts in several western states and cities have been more active. If these organizations can mobilize and influence legislators or other public officials, they could try to promote options 3 (violation) or 4 (street warning). These drug policy reformers can form alliances with African-American and Hispanic leaders which would be focused solely on the single issue of changing MPV arrest policies to reduce ethnic disparities in arrest. Such a coalition could likely get the (relatively liberal) New York City council to pressure the Mayor and NYPD to change its marijuana enforcement practices away from proactive policing of marijuana users in quasi-public settings, and especially away from relying primarily upon detention (option 1) as the main punishment. The NYPD previously (1980-1994) issued street warning (option 4) or ignored it (option 5). At the same time, drug policy reformers could seek change New York State law (221.10) so that public smoking of small amounts of marijuana becomes a violation (221.05) [as specified above].

Conclusion

The appropriate policies for using police powers of arrest, and the procedures and punishments for violators for marijuana smoking or possession in public places is a small issue in the ongoing processes of democracy. While recognizing that the majority of citizens do not approve of use and probably don't want marijuana smoking in public, support for this civic norm appears very weak and immaterial to the citizenry. Indeed, MPV was rarely an issue in NYC when police ignored or warned marijuana smokers (1980-1994). Yet a small part of the population, especially African-American and Hispanics, who are current marijuana users (consuming in concealed but public settings) disproportionately are impacted by the current arrest and detain policy. The Mayor, Police Commissioner, or even City Council could change police procedures to dramatically reduce the detention of massive numbers of low-level offender for MPV charges. Reducing proactive police enforcement and choosing other procedures (especially issuance of DATs and street warnings) could be significantly less harsh and yet maintain the civic norm against marijuana smoking. Such shifts would substantially reduce the numbers of MPV arrestees detained for 16-36 hours, probably reduce ethic disparities somewhat, and lower governmental expenditures currently devoted to processing thousands of detainees. This is a policy issue that deserves more systematic public consideration and policy debate than exists in 2007 in New York City.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R01 DA/CA13690-05), from the Marijuana Policy Project, and by National Development and Research Institutes. Points of view and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the positions of these funding organizations nor National Development and Research Institutes. The authors acknowledge with appreciation the contributions to this paper by Flutura Bardhi, Luther Elliott, Jan Moravék, and Kevin Sabet.

Biography

Brief Author Bios

Bruce D. Johnson (Ph.D. Columbia University) is one of the nation's authorities on the criminality and illicit sales of drugs in the street economy and among arrestees and minority populations. He directs the Institute for Special Populations Research at the National Development and Research Institutes. He is a professional researcher with five books and over 130 articles based upon findings emerging from over 30 different research and prevention projects funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and National Institutes of Justice. He also directs the nation's largest pre- and postdoctoral training program in the U.S.

Andrew Golub, (Ph.D. Carnegie Mellon University) is a principal investigator at National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. His research focuses upon understanding drug use trends in context and often involves the integration of quantitative and qualitative research methods. He also integrates information from multiple complex data sets and conducts secondary analyses of national data sets. He has over 50 publications in peer reviewed journals.

Eloise Dunlap, Ph.D. (Ph.D, Berkeley) has extensive qualitative experience in research and publications that address the role of crack and marijuana users, and drug-abusing African-American families, and their households. She is/has been Principal Investigator of six NIDA-funded projects.

Stephen J. Sifaneck, (Ph.D. CUNY Graduate Center) is a Professor in the Justice Studies Program at Berkeley College in Manhattan. His publications include articles and chapters about the sale and use of marijuana, heroin and prescription drugs, ethnographic research methodologies, and subcultural urban issues.

Footnotes

Note: The sale of even small amounts of marijuana in public locations would remain a class A or B misdemeanor as currently defined in NY Penal Law. None of the options here would change laws against marijuana sellers. This essay also does not consider a policy option that is common in many US states that did not decriminalize marijuana: Arrest and prosecute marijuana possessors and sellers under the same legal statutes as heroin/crack/cocaine. The latter policy arrests persons for possession of small amounts of marijuana, detains them for several days, and jails or imprisons many (see Reuter, Hirschfield, Davies. 2001).

The NYPD has not reported any homicide or serious crime, however, that was solved due to locating a suspect who had only a previous marijuana possession charge.

Repeated violators would be subject to greater fines. See full statute.

Indeed, some unknown proportion of arrestees for MPV may have received DATs (and not been detained); MPV arrestees from middle class backgrounds with good identification often receive DATs. Likewise, most juveniles are released to guardians following MPV stops.

References

- Amnesty International. United States of America: Police Brutality and Excessive Force in the New York City Police Department. 1996 AMR 56/036/1996. Available at http://web.amnesty.org.

- Allison Graham. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. Boston: Little Brown; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Becket Katherine, Nyrop Kris, Pfingst Lori. Race, drugs and policing: Understanding disparities in drug delivery arrests. Criminology. 2005a;44:105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Becket Katherine, Nyrop Kris, Pfingst Lori, Bowen Melissa. Drug use, drug possession arrests, and the question of race: Lessons from Seattle. Social Problems. 2005b;52:419–441. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein Alfred, Wallman Joel., editors. The Crime Drop in America. Revised New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton William, Knobler Peter. Turnaround: How America's Top Cop Reversed the Crime Epidemic. New York: Random House; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie RJ, Whitebread C. The forbidden fruit and the tree of knowledge: An inquiry into the legal history of American marijuana prohibition. Virginia Law Review. 1970;56(6):971–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Brown David T. Cannabis. Amsterdam: Overseas Publishers Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Coker Donna. Supreme Court review: Addressing the real world of racial injustice in the criminal justice system. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 2003;93:827–879. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis Richard. The improbable transformation of inner-city neighborhoods: Crime, violence, drugs, and youth in the 1990s. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1998;88:1233–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap Eloise, Johnson Bruce D, Sifaneck Stephen J, Benoit Ellen. Sessions, cyphers, and parties: Settings for informal social controls of blunt smoking. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse. 2005;4(34):43–80. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_03. 244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap Eloise, Benoit Ellen, Sifaneck Stephen J, Johnson Bruce D. Social constructions of dependency by blunts smokers: Qualitative reports. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine Mitch. Pot Politics: Marijuana and the Cost of Prohibition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eterno John A. Zero tolerance policing in democracies: The dilemma of controlling crime without increasing police abuse of power. Police Practice. 2001;2:189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Feeley Malcolm M. The process is the punishment : Handling cases in a lower criminal court. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn Kevin. Arrests soar in crackdown on marijuana. New York Times. 1998 November 17;:1. Section B. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn Kevin. Racial bias shown in police searches, state report asserts. New York Times. 1999 December 1. [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew., editor. The Cultural/Subcultural Contexts of Marijuana Use at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Binghamton, NY: Haworth; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D. Cohort changes in illegal drug use among arrestees in Manhattan: From the heroin injection generation to the blunted generation. Substance Use and Misuse. 1999;34(13):1733–1763. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D. The rise of marijuana as the drug of choice among youthful arrestees. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Justice NCJ; 2001. Research in Brief. 187490. [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D. How much do Manhattan arrestees spend on drugs? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(3):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D, Dunlap Eloise. The growth in marijuana use among American youths during the 1990s and the extent of blunt smoking. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2005;4(34):1–21. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D, Dunlap Eloise. Smoking marijuana in public: The spatial and policy shift in New York City's arrests, 1992-2003. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-22. Online journal-- http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/3/1/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D, Dunlap Eloise. The race/ethnic disparities in marijuana arrests in New York City. Criminology and Public Policy. 2007;6(1):131–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D, Taylor Angela, Eterno John. Quality-of-life policing: Do offenders get the message? Policing: International Journal of Police Strategies and Management. 2003;26(4):690–707. doi: 10.1108/13639510310503578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub Andrew, Johnson Bruce D, Taylor Angela, Liberty Hilary. The validity of arrestee self-reports: Variations across questions and persons. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19(3):477–502. [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon Lester, Bakalar James B. Marijuana: The Forbidden Medicine. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Guiliani Rudolph W, Kurson Ken. Leadership. New York: Hyperion; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Wayne, Pacula Rosalie L. Cannabis Use and Dependence: Public Health and Public Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt Bernard E. Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. Drug Use Declared: Findings from the 2005/06 British Crime Survey. England and Wales. London, England: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Bruce D, Golub Andrew. Dependence on and treatment for street drugs among Manhattan arrestees. In: Cole Spencer., editor. New Research on Street Drugs. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Bruce D, Bardhi Flutura, Sifaneck Stephen J, Dunlap Eloise. Marijuana argot as subculture threads: Social constructions by users in New York City. British Journal of Criminology. 2006a;46(1):46–77. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Bruce D, Golub Andrew, Deren Sherry, Des Jarlais Don C, Fuller Crystal, Vlahov David. The nonimpact of the expanded syringe access program upon heroin use, injection behaviors, and crime indicators in New York City and State. Justice Research and Policy. 2006b;8(1):27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Bruce D, Golub Andrew, Dunlap Eloise. The rise and decline of drugs, drug markets, and violence in New York City. In: Blumstein Alfred, Wallman Joel., editors. The Crime Drop in America. Revised New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006c. pp. 164–206. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Bruce D, Golub Andrew, Dunlap Eloise, Sifaneck Stephen J, McCabe James. Policing and social control of public marijuana use and selling in New York City. Law Enforcement Executive Forum. 2006d;6(5):55–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Bruce D, Ream Geoffrey, Dunlap Eloise, Sifaneck Stephen J. Civic norms and etiquettes regarding marijuana use in public settings in New York City. Substance Use and Misuse. 2007;43 doi: 10.1080/10826080701801477. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelling George L, Coles Catherine M. Fixing broken windows: Restoring order and reducing crime in our communities. New York: Free Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kelling George L, Sousa William H., Jr . Civic Report No 22. New York: Manhattan Institute; 2001. Do police matter? An analysis of the impact of New York City's police reforms. Available at www.manhattan-institute.org. [Google Scholar]

- King Ryan S, Mauer Marc. The war on marijuana: The transformation of the war on drugs in the 1990s. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3 doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-6. www.harmreductionjournal.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kleiman Mark AC. Marijuana: Costs of Abuse, Costs of Control. New York: Greenwood Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]