Abstract

The nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors controls calcium signaling in T lymphocytes. In this study, we have identified a crucial regulatory role of the transcription factor NFATc2 in T cell–dependent experimental colitis. Similar to ulcerative colitis in humans, the expression of NFATc2 was up-regulated in oxazolone-induced chronic intestinal inflammation. Furthermore, NFATc2 deficiency suppressed colitis induced by oxazolone administration. This finding was associated with enhanced T cell apoptosis in the lamina propria and strikingly reduced production of IL-6, -13, and -17 by mucosal T lymphocytes. Further studies using knockout mice showed that IL-6, rather than IL-23 and -17, are essential for oxazolone colitis induction. Administration of hyper-IL-6 blocked the protective effects of NFATc2 deficiency in experimental colitis, suggesting that IL-6 signal transduction plays a major pathogenic role in vivo. Finally, adoptive transfer of IL-6 and wild-type T cells demonstrated that oxazolone colitis is critically dependent on IL-6 production by T cells. Collectively, these results define a unique regulatory role for NFATc2 in colitis by controlling mucosal T cell activation in an IL-6–dependent manner. NFATc2 in T cells thus emerges as a potentially new therapeutic target for inflammatory bowel diseases.

Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two key forms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) in humans (1–3). Growing evidence indicates a central role of a genetically determined dysregulation of the mucosal immune response toward the resident bacterial flora in the pathogenesis of human IBD (4). This pathological immune response is characterized by an accumulation of antigen-presenting cells and T cells that represent the vast majority of activated mononuclear cells infiltrating the gut (5–8).

The differentiation and activation of CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria play a major role in the pathogenesis of IBD (9). Whereas CD is associated with increased production of Th1-like cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF, the cytokine profile in chronic UC is characterized by the increased production of several Th2 cytokines, such as IL-5, -6, and -13 (7, 8, 10, 11). Interestingly, both Th1- and Th2-type cytokines have been shown to play an important pathogenic role in various animal models of IBD, suggesting that both T helper subsets can induce chronic intestinal inflammation in vivo (11, 12). This pathogenic function of Th1 and Th2 cells can be counteracted by immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, which are produced by regulatory T cells and Th1 cells (11–15).

T lymphocytes transit through sequential stages of cytokine activation, commitment, silencing, and physical stabilization during polarization into effector subsets, a process that is tightly controlled by regulatory transcriptional events (3, 16, 17). Although transcription factors such as STAT-6, GATA-3, c-Maf and JunB have been shown to control Th2 cytokine production, STAT-1, STAT-4, and T-bet are associated with signaling events in Th1 cells and play a key role in Th1-specific cytokine production in peripheral T cells (16, 17). In the mucosal immune system, several studies have suggested important roles for STAT-4 and T-bet in Th1 cell effector functions in the gut in experimental colitis and CD (9, 18, 19). However, the functional role of other T cell transcription factors such as nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) in IBD is poorly understood.

The NFAT family of transcription factors consists of five members: NFATc1 (also known as NFATc or NFAT2), NFATc2 (NFATp or NFAT1), NFATc3 (NFATx or NFAT4), NFATc4 (NFAT3), and NFAT5 (TonEBP or OREBP) (20–23). All NFAT proteins have a highly conserved DNA-binding domain that is structurally related to the DNA-binding domain of the REL family of transcription factors (23, 24). This REL-homology region (RHR) is the unifying characteristic of NFAT proteins and confers a common DNA-binding specificity.

NFAT proteins seem to play a pivotal role in the activation and differentiation of T lymphocytes and are activated by calcium signaling (22–25). In fact, calcium-bound calmodulin activates the calcineurin phosphatase complex, which dephosphorylates NFATc1 and causes its import into the nucleus, where NFATc1 and its nuclear partner, NFATn, cooperatively bind to DNA. NFATc1 complexes act as “coincidence detectors” and allow the integration of multiple signaling pathways at the level of DNA binding. In addition to NFATc1, NFATc2 is constitutively expressed in T cells and controls T cell activation and survival (22, 24–26). Consistently, NFATc2 KO mice developed a hyperproliferative syndrome with increased numbers of peripheral lymphocytes caused by defects in activation-induced cell death and reduced expression of several proapoptotic genes, such as CD95L and TNF (27–29). NFATc2-deficient mice also showed alterations in T cell cytokine production. Whereas NFATc2-deficient splenic T cells displayed reduced early IL-4 production, increased levels of IL-4 were found at later time points during Th2 development, suggesting that NFATc2 is important for cytokine production by peripheral T cells (27, 28).

In contrast to peripheral T cells, the function of NFATc2 in mucosal T cells remains largely unknown. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the role of NFATc2 signal transduction in intestinal inflammation. A significantly higher expression of NFATc2 was found in UC tissues compared with control samples. Furthermore, NFATc2 was found to play a pivotal regulatory role in T cell–dependent experimental colitis by controlling IL-6–dependent T cell activation.

RESULTS

Enhanced expression of NFATc2 in patients with IBDs

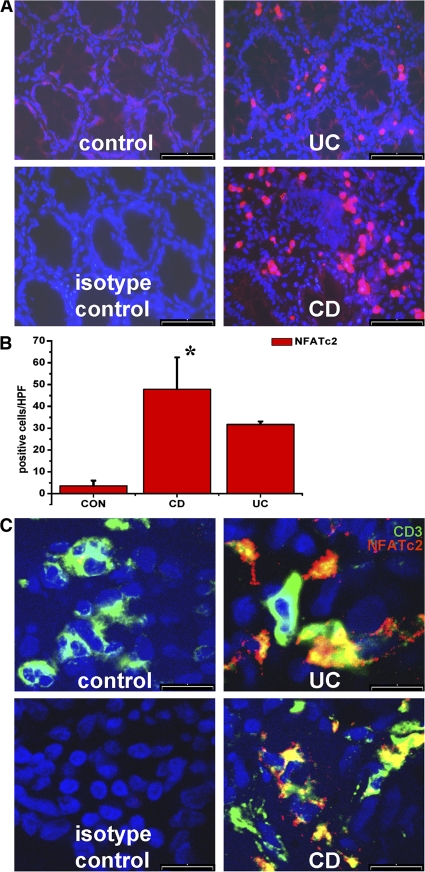

The NFAT plays a fundamental role in controlling calcium-dependent T cell activation (23, 30–32). As T cells have been suggested to play a major role in patients with IBDs, we analyzed expression of NFATc2 by immunohistochemistry. Accordingly, colonic cryosections from IBD patients were stained with NFATc2-specific antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1 (A and B), NFATc2-positive cells were found in the lamina propria of control patients, and the number of these cells was significantly increased in patients with IBD.

Figure 1.

Enhanced expression of NFATc2 transcription factors in patients with IBDs compared with control patients. (A) Immunohistochemistry for NFATc2 expression. Colon cross sections were incubated with NFATc2-specific antibodies and analyzed by microscopy. An increased expression of NFATc2 was observed in sections from UC and CD patients compared with control patients. Representative stainings from 5 to 10 patients per group are shown. (B) Quantitative analysis of positive cells revealed a significantly increased number of NFATc2-positive cells in IBD patients compared with control patients. Data represent mean values ± the SD per high power field. *, P < 0.05. (C) Detection of NFATc2-expressing T cells in the lamina propria of patients with IBDs. Samples from CD, UC, and control patients were stained with anti-NFATc2 and anti-CD3 antibodies, followed by confocal laser microscopy. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Representative pictures are shown. Staining with an isotype control antibody served as negative control. CD3/NFATc2 double-positive, yellowish cells were seen in the lamina propria in CD and UC. Bars: (A) 80 μm; (C) 30 μm.

T lymphocytes are key effector cells in the pathogenesis of IBD and produce several proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to tissue destruction in IBD (4, 12). To determine whether T lymphocytes in IBD express NFAT proteins, double staining for CD3 and NFATc2 was performed (Fig. 1 C). Interestingly, many T lymphocytes in the gut of IBD patients were positive for NFATc2, which is consistent with a potential regulatory role of this transcription factor in mucosal T cells.

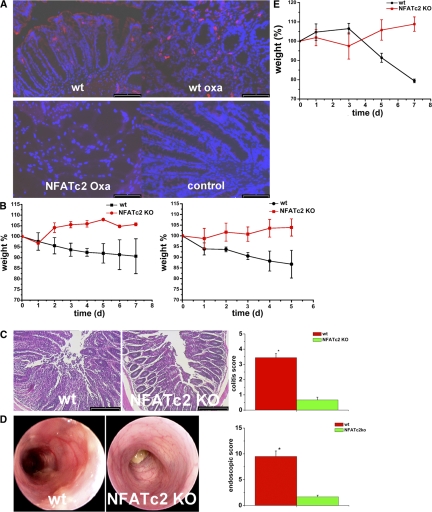

A key regulatory role of NFATc2 in oxazolone-induced colitis

In subsequent studies, we found an induction of NFATc2 expression in WT mice with oxazolone-induced colitis as compared with unchallenged mice, which is consistent with a potential regulatory role of NFATc2 in T cell–mediated colitis (Fig. 2 A). To analyze the functional role of NFATc2 in experimental colitis, we then took advantage of genetically engineered mice in which the NFATc2 gene was inactivated by homologous recombination (27). In these studies, we determined whether NFATc2-deficient mice exhibit an altered susceptibility to oxazolone colitis that (similarly to UC) is characterized by IL-5 and -13 production by T cells (33, 34). It was found that NFATc2-deficient mice were almost completely protected from oxazolone colitis. Although WT mice challenged with oxazolone showed a marked weight loss, no diarrhea and weight loss were noted in mice lacking NFATc2 (Fig. 2 B). Consistently, histological analysis showed significant suppression of colitis activity in NFATc2-deficient mice compared with WT mice after administration of oxazolone (Fig. 2 C). Finally, endoscopic analysis revealed significant suppression of oxazolone-induced colitis in the former as compared with the latter group of mice (Fig. 2 D).

Figure 2.

A regulatory role of NFATc2 in oxazolone-induced experimental colitis. (A) Enhanced expression of the NFATc2 transcription factor in oxazolone-induced colitis. Colonic cryosections from WT and NFATc2 KO mice were incubated with anti-NFATc2 antibodies followed by tyramide signal amplification. An increased expression of NFATc2 was observed in colonic tissue from WT mice with oxazolone colitis (WT oxa) as compared with WT unchallenged mice. Colonic tissue from NFATc2 KO mice (NFATc2 oxa) served as negative control and did not reveal any specific staining as expected. (B) Oxazolone colitis was induced by sensitizing mice with oxazolone, followed by intrarectal administration of the hapten reagent after 1 wk. The body weight of the mice was monitored after oxazolone rechallenge at the indicated time points. Mean values ± the SEM from two representative experiments out of six are shown. The average weight of the mice at the beginning of the experiments was 22.9 g (WT group) and 22.5 g (NFATc2 KO group), respectively. For this experiment, 6 WT and 7 NFATc2 KO mice were used. (C) Histological sections (left) of colonic inflammation in WT or NFATc2-deficient mice upon oxazolone administration. Signs of inflammation such as goblet cell depletion, ulcers, and accumulation of mononuclear cells were noted in WT mice, whereas NFATc2 KO mice showed little or no evidence of colitis. Quantitative histopathologic assessment of colitis activity (right) showed a significant (*P < 0.05) protection from inflammation and tissue injury in NFATc2 KO mice compared with WT mice. Data represent mean values ± the SEM from one representative experiment out of six. (D) High-resolution miniendoscopic analysis (left) of the colon of NFATc2 KO and WT mice in oxazolone colitis. Marked erosions and ulcers were seen in the WT group, whereas an almost normal colon architecture was noted in NFATc2-deficient mice. Quantitative endoscopic analysis (right) of inflammation (MEICS score) in WT and NFATc2 KO mice in oxazolone colitis was done at day 2 after administration of oxazolone. A significantly (P < 0.05) lower endoscopic score was observed in NFATc2-deficient mice compared with WT mice. (E) Adoptive T cell transfer from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in SCID mice. CD4+ T cells were transferred into CB-17/SCID mice, followed by oxazolone sensitization and intrarectal oxazolone administration. The body weight of reconstituted mice was analyzed at indicated time points. Mean values ± SEM from one representative experiment out of three are shown. Whereas mice reconstituted with WT T cells showed a marked weight loss, mice given NFATc2-deficient T cells were protected from colitis and gained weight. For this experiment five SCID mice in each group were used. Bars: (A) 80 μm; (C) 100 μm.

To prove that the observed protective effect in NFATc2-deficient mice was caused by T lymphocytes, we next performed adoptive transfer studies. Accordingly, splenic CD4+ T lymphocytes from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice were adoptively transferred into immunodeficient mice, followed by sensitization and challenge of the reconstituted mice with oxazolone. As shown in Fig. 2 E, mice given WT T cells developed severe colitis with weight loss, whereas mice reconstituted with NFATc2-deficient T cells were protected from such colitis, suggesting that NFATc2 mediates its pathogenic role in oxazolone colitis via its effects on T lymphocytes.

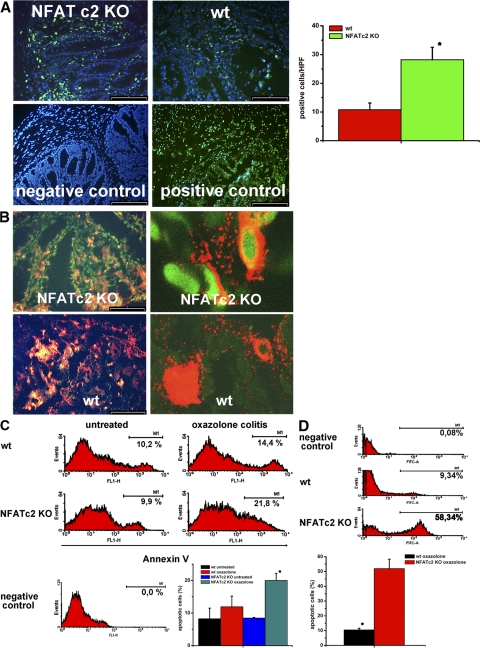

Increased apoptotic rate of NFATc2-deficient lamina propria T cells in oxazolone-induced colitis

Because it is known that NFATc2-deficient mice have a defect in lymphocyte apoptosis (27, 29), we next assessed the apoptotic rate of lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) in oxazolone-induced colitis. Accordingly, cryosections of oxazolone-treated WT and NFATc2 KO mice were stained by TUNEL assays (Fig. 3 A). Surprisingly, a significantly higher number of apoptotic cells was observed in NFATc2-deficient mice as compared with WT control mice (Fig. 3 A). Furthermore, double staining analysis for CD3 and TUNEL (Fig. 3 B) revealed a higher number of apoptotic T cells in the former as compared with the latter mice, suggesting that NFATc2-deficient lamina propria T cells in oxazolone colitis are more susceptible to undergo programmed cells death than WT T cells. To further analyze this possibility, we analyzed freshly isolated T cell enriched lamina propria cells from WT and NFAT-deficient mice for apoptosis by FACS analysis using 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) and anti–annexin V antibodies. In oxazolone-induced colitis, a significantly higher rate of apoptotic lamina propria cells was seen in NFATc2 KO mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3 C). Furthermore, there was a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic T lymphocytes in the lamina propria of NFATc2 KO mice compared with WT mice in oxazolone-induced colitis (Fig. 3 D). Interestingly, NFATc2-deficient T cells expressed lower amounts of antiapoptotic proteins, such as bcl-xl and bcl-2, compared with WT T cells in colitis (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072484/DC1). As NFATc2-deficient T cells are normally resistant to undergo apoptosis (27, 29), our data thus suggested the possibility that external factors such as the cytokine milieu may cause increased mucosal NFATc2−/− T cell apoptosis in experimental colitis.

Figure 3.

Augmented T cell apoptosis in the colon of NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis. (A) Cryosections of colonic tissue from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis were made, and apoptotic cells were stained using the TUNEL reaction. Staining of the nuclei was done with DAPI. Representative stainings from WT and NFATc2 KO mice, as well as negative and positive control stainings are shown (left). (right) Quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells in 10 randomly selected high power fields per sample. Data represent mean values ± the SD. A significantly (P < 0.05) higher number of apoptotic cells was observed in colonic tissue from NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis compared with WT control mice. Bar, 100 μm. (B) Double staining analysis of colonic tissue from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis using TUNEL assays and anti-CD3 antibodies (left). Cryosections were analyzed by confocal laser microscopy for apoptotic T cells, and representative pictures are shown (right). A higher number of apoptotic/CD3 double-positive cells (FITC TUNEL staining; Cy3 stained CD3) was observed in NFATc2 mice compared with WT mice. (C) An increased number of apoptotic LPMCs in NFATc2-deficient mice upon administration of oxazolone. LPMCs from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice were isolated and stained with 7-AAD and anti–Annexin V antibodies for FACS analysis. In comparison to WT cells, LPMCs from NFATc2-deficient mice showed an increased number of apoptotic cells in oxazolone-induced colitis. Representative FACS analyses of different groups of mice for annexin V are shown. Quantitative analysis of apoptotic LPMCs was performed in three independent experiments (bottom). Data represent mean values ± the SD. There was a significant (*, P < 0.05) increase of apoptotic LPMCs in NFATc2-deficient mice as compared with WT control mice. (D) Increased number of apoptotic lamina propria CD4+ T cells in NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis. LPMCs from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice were prepared, and CD4+ T cells were isolated by using the MACS-System. Cells were stained with 7-AAD and anti–Annexin V antibodies for subsequent analysis (top). Lamina propria T cells from NFATc2 KO mice showed an increased percentage of apoptotic cells in colitis compared with WT mice. Quantitative analysis of apoptotic CD4 T cells was performed in two experiments (bottom). Data represent mean values ± the SD. There was a significant (*, P < 0.05) increase of apoptotic lamina propria T cells in NFATc2-deficient mice compared with WT control mice.

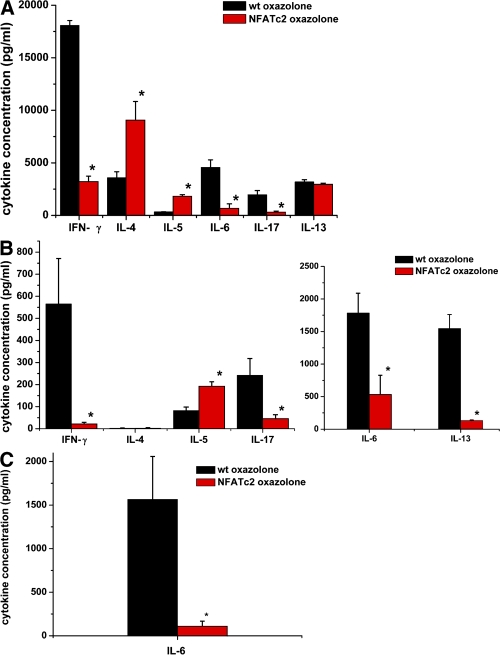

Reduced production of IL-6, -13, and -17 by NFATc2-deficient lamina propria T cells

To further test the aforementioned hypothesis, we next assessed the effects of NFATc2 on T cell cytokine production in oxazolone-induced colitis. Splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from NFATc2-deficient mice produced significantly lower amounts of IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-17 but higher amounts of IL-4 than T cells from WT mice (Fig. 4 A). Furthermore, colonic LPMCs from NFATc2-deficient mice produced significantly lower amounts of IL-6, -13, and -17 in oxazolone-induced colitis compared with control WT cells (Fig. 4 B). Whereas T cell survival at the end of the cell cultures differed by only ∼10% between the groups (79% in WT vs. 70% in NFAT KO mice), the production of the above cytokines was reduced by >70% in the absence of NFATc2, suggesting that NFATc2 controls cytokine production by mucosal T cells. In contrast to IL-6, -13, and -17, no significant changes in IL-4 production were noted. Furthermore, a significant induction of IL-5 production by NFATc2-deficient cells was observed, suggesting that only distinct cytokines produced by T cells are reduced by the absence of the transcription factor NFATc2. The reduced IL-17 production by T cells lacking NFATc2 was remarkable, as both splenic and lamina propria cells from NFATc2-deficient mice expressed normal or even increased amounts of the Th17 master transcription factor ROR-γt (unpublished data). However, IL-17F production was also reduced in the absence of NFATc2 as compared with WT mice in oxazolone colitis (Fig. S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072484/DC1), suggesting that NFATc2 controls Th17 cytokine production in experimental colitis.

Figure 4.

Cytokine production in oxazolone-induced colitis. (A) Cytokine production by splenic CD4+ T cells from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis. CD4+ T cells were stimulated with antibodies to CD3 and CD28 for 48 h, followed by analysis of culture supernatants using cytomix (see Materials and methods). Data represent mean values of four to eight mice per group. CD4+ T cells from WT mice produced significantly (P < 0.05) higher amounts of IFN-γ, but lower amounts of IL-4 than NFATc2-deficient T cells. Furthermore, a significantly lower production of IL-6 and -17 was observed in the supernatant of NFATc2-deficient CD4+ T cells in comparison to WT T cells. (B) Cytokine production by T cell–enriched lamina propria cells from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis. Lamina propria cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin, and the cell supernatant was analyzed using cytomix. Data represent mean values of three to six mice per group. T cells from WT mice produced higher amounts of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-13, and IL-17 when compared with cells from NFATc2-deficient mice. At the end of the culture, cell survival rates differed by ∼10% between WT and KO cells only, suggesting that the marked differences in cytokine production under our experimental conditions are not caused by primary effects on T cell apoptosis. (C) IL-6 production by purified CD4+ lamina propria T cells from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis. LPMCs from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice were prepared, and CD4+ T cells were isolated by using the MACS System. T cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin, and supernatants were analyzed using an IL-6–specific ELISA. Data represent mean value ± the SD from two experiments with four mice per group. CD4+ lamina propria T cells from WT mice produced significantly (P < 0.05) higher amounts of IL-6 compared with cells from NFATc2-deficient mice.

In subsequent experiments, we purified lamina propria CD4+ T cells from WT and NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis using immunomagnetic beads, and thereby determined IL-6 production. As shown in Fig. 4 C, NFATc2-deficient lamina propria T cells produced significantly less IL-6 than WT T cells, suggesting that NFATc2 controls IL-6 production by mucosal T cells in experimental colitis. Consistently, a lower amount of IL-6–expressing cells was noted in the lamina propria of NFATc2 KO mice compared with WT mice in oxazolone colitis (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072484/DC1).

IL-6 and -13, but not the IL-23/IL-17A axis, is required for oxazolone-induced colitis

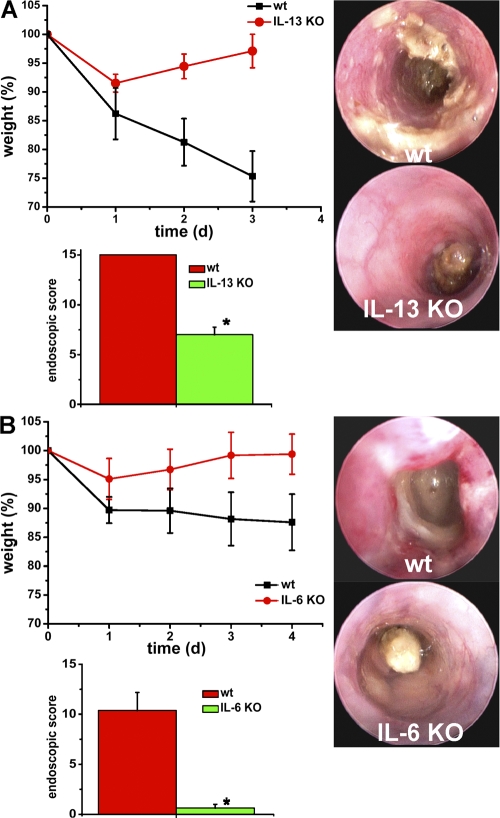

To determine the functional role of the aforementioned cytokines in vivo, we next performed studies in oxazolone-induced colitis using specific KO mice. As shown in Fig. S4 (A and B, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072484/DC1), both IL-23p19– and IL-17A–deficient mice showed no significant reduction of colitis activity, as determined by weight curves, endoscopic scores, and histological assessment (unpublished data), suggesting that other cytokines produced by T cells could play a pathogenic role. Interestingly, IL-6 levels produced by IL-17A– and IL-23p19–deficient lamina propria cells were comparable to WT cells (Fig. S2). However, mice deficient for IL-13 (Fig. 5 A) and IL-6 (Fig. 5 B) showed significant protection from oxazolone-induced colitis. These mice showed a reduction of weight loss and endoscopic colitis activity compared with WT mice. Collectively, these data suggested that IL-6 and -13, rather than IL-23 and -17A, play a major pathogenic role in oxazolone colitis.

Figure 5.

Reduced capacity of IL-6 and IL-13–deficient mice to develop oxazolone-induced colitis. (A) Oxazolone colitis was induced in IL-13–deficient mice and WT mice by sensitizing mice with oxazolone, followed by intrarectal administration of the hapten reagent after 1 wk. The body weight of the mice was monitored after oxazolone rechallenge at indicated time points (top left). Mean values ± SEM from one representative experiment out of two are shown. The average weight of mice at the beginning of the experiment was 25.8 g (WT group) and 25.8 g (IL-13 KO group), respectively. For this experiment, 5 WT and 5 IL-13 KO mice were used. Endoscopic assessment of colonic inflammation in WT (A, top right) or IL-13–deficient (A, bottom right) mice upon oxazolone administration. In contrast to WT mice, IL-13–deficient mice showed little evidence of colitis. Mean endoscopic scores ± the SEM from one representative experiment out of two are shown (bottom left). (B) IL-6–deficient mice and WT mice were sensitized with oxazolone, followed by intrarectal administration of the hapten reagent after 1 wk. The body weight of the mice was monitored after oxazolone rechallenge at the indicated time points. Mean values ± the SEM from one representative experiment out of three are shown (top left). The average weight of mice at the beginning of the experiment was 25.9 g (WT group) and 24.5 g (IL-6 KO group), respectively. For this experiment, four WT and four IL-6 KO mice were used. One representative experiment out of three is shown. Endoscopic assessment of colonic inflammation in WT (B, top right) or IL-6–deficient (B, bottom right) mice upon oxazolone administration. IL-6–deficient mice were significantly (*, P < 0.05) protected from oxazolone-induced colitis.

IL-6 signaling reverses the protective effect of NFATc2 deficiency in experimental colitis

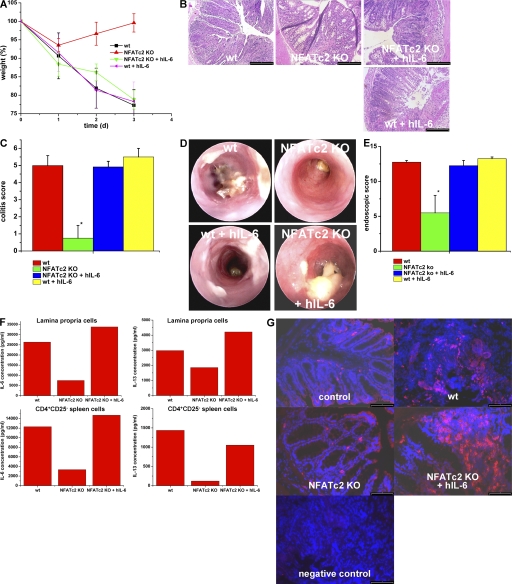

The above findings were consistent with the hypothesis that the reduced susceptibility of NFATc2-deficent mice for oxazolone-induced colitis is caused by suppression of IL-6 production by mucosal T cells with consecutive T cell apoptosis. To test whether activation of IL-6 signaling in vivo could overcome the reduced susceptibility of NFATc2-deficient mice to oxazolone-induced colitis, we next treated NFATc2-deficient mice upon oxazolone administration with hyper-IL-6. In these studies, NFATc2-deficient mice were injected i.p. with hyper-IL-6 1 d before intrarectal challenge with oxazolone. Interestingly, NFATc2-deficient mice given hyper-IL-6 showed normal susceptibility to oxazolone-induced colitis comparable to WT control mice, as shown by weight curves (Fig. 6 A), histopathologic criteria (Fig. 6, B and C), and miniendoscopic criteria (Figs. 6, D and E). In fact, hyper-IL-6 abrogated the protection of NFATc2 KO mice in oxazolone-treated mice and induced mucosal and systemic IL-6 and -13 production as well as an increased local T cell number (Fig. 6, F and G) strongly suggesting that the pathogenic role of NFATc2 in T cell-mediated colitis is caused by regulation of IL-6 production.

Figure 6.

Administration of hyper-IL-6 restores the susceptibility of NFATc2-deficient mice to oxazolone-induced colitis. (A) Oxazolone colitis was induced by sensitizing mice with oxazolone, followed by intrarectal administration after 7 d and monitoring of the body weight at indicated time points. Hyper IL-6 (hIL-6; 1 μg per mouse) was given i.p. before oxazolone administration. Weight curves from one representative experiment out of three are shown. Data represent mean values ± the SEM. Hyper-IL-6 administration led to colitis development and weight loss in oxazolone-treated NFATc2 KO mice, but had little effect on colitis activity in WT mice. This experiment was performed three times with groups of four to five mice. (B) Histological analysis of colonic inflammation in WT and NFATc2-deficient mice given PBS or hyper-IL-6. Signs of inflammation such as goblet cell depletion, erosions, and accumulation of mononuclear cells were noted in NFATc2-deficient mice treated with hyper-IL-6, but not control-treated NFATc2 KO mice. (C) Quantitative histopathologic assessment of colitis activity showed a significant (P < 0.05) protection from inflammation and tissue injury in NFATc2-deficient mice compared with WT mice, whereas no significant difference was noted between WT mice and NFATc2 KO mice given hyper-IL-6. Data represent mean values ± the SEM. (D) Endoscopic analysis of the colon of WT and NFATc2-deficient mice at day 2 after application of oxazolone. Oxazolone-induced erosions and ulcers were seen in the WT and NFATc2/hyper-IL-6 groups, whereas a normal colon architecture was noted in NFATc2-deficient mice. (E) Quantitative endoscopic score of inflammation (MEICS score). A significantly lower endoscopic score was observed in NFATc2-deficient mice compared with WT mice and NFATc2-deficient mice treated with hyper-IL-6. (F) IL-6 and -13 cytokine production by isolated CD4+CD25− splenic T cells and LPMCs in oxazolone colitis. Whereas NFATc2-deficient cells produced lower amounts of IL-6 and -13 than WT cells, hyper-IL-6 administration led to a strong induction of IL-6 and -13 production by cells lacking NFATc2. No changes in IFN-γ production were noted between NFATc2 KO mice and NFATc2 KO mice given hIL-6 (not depicted). (G) Increased numbers of CD4+ T cells in NFATc2-deficient mice after administration of hIL-6 in oxazolone colitis. Cryosections of colonic tissue were incubated with anti-CD4 antibodies and stained with conjugated Cy3 antibodies. An increased number of CD4+ T cells was observed in colonic tissue from WT mice during oxazolone-induced colitis compared with NFATc2 KO mice. After administration of hIL-6, NFATc2-deficient mice showed increased numbers of CD4+ T cells compared with NFATc2 mice without hIL-6 administration. Negative control staining is shown. Bars: (B) 100 μm; (G) 80 μm.

IL-6 deficiency in T cells controls mucosal inflammation in oxazolone-induced colitis

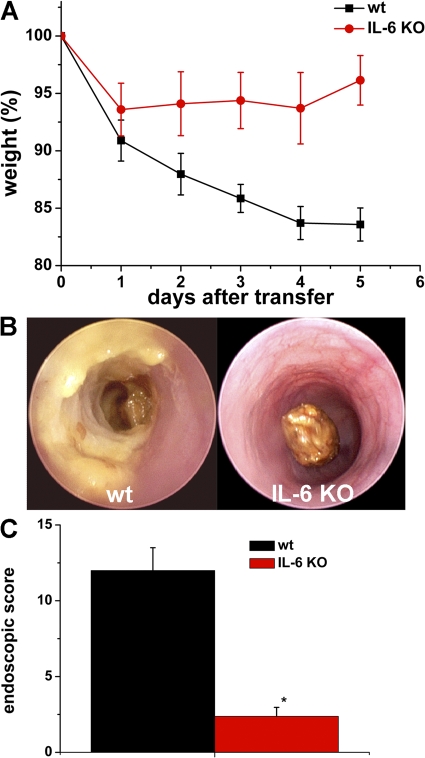

As the above findings indicated a key role of IL-6 signaling in oxazolone colitis, we determined in a final series of studies the effect of IL-6 deficiency in T cells on mucosal inflammation in oxazolone-induced colitis. Accordingly, splenic CD4+ T cells were purified from both WT and IL-6–deficient mice and adoptively transferred into immunodeficient mice, followed by induction of oxazolone-induced colitis. As shown in Fig. 7 A, mice given WT T cells developed severe colitis with weight loss, whereas mice reconstituted with IL-6–deficient T cells were protected from such colitis. Furthermore, endoscopic analysis showed significant reduction of colitis activity in the latter compared with the former mice (Figs. 7, B and C), suggesting that T cell–derived IL-6 controls mucosal inflammation in oxazolone-induced colitis.

Figure 7.

Adoptive T cell transfer from WT and IL-6–deficient mice in SCID mice. (A) CD4+ T cells from WT and IL-6 donor mice were transferred into CB-17/SCID mice, followed by oxazolone sensitization and intrarectal oxazolone administration. The body weight of reconstituted mice was analyzed at the indicated time points. Mean values ± the SEM from one representative experiment are shown. Whereas mice reconstituted with WT T cells showed a marked weight loss, mice given IL-6–deficient T cells were protected from colitis. For this experiment, four SCID mice in each group were used. (B) Endoscopic assessment of colonic inflammation of SCID mice reconstituted with WT (left) or IL-6–deficient (right) T cells upon oxazolone administration. Endoscopy was performed 2 d after intrarectal oxazolone challenge. (C) Quantitative endoscopic analysis of inflammation (MEICS score) of SCID mice in oxazolone colitis was done 2 d after administration of oxazolone. A significantly (P < 0.05) lower endoscopic score was observed in SCID mice reconstituted with T cells from IL-6–deficient mice as compared with the WT group.

DISCUSSION

UC is an IBD characterized by chronic relapsing, immunologically mediated inflammation of the intestine (1, 35). Here, we have identified a central pathogenic role for the transcription factor NFATc2 in chronic intestinal inflammation. In an initial series of studies, we demonstrated that NFATc2 expression is increased in lamina propria T cells in UC compared with control patients. We then took advantage of genetically altered mice that lack NFATc2 to uncover a critical role for this factor in chronic intestinal inflammation. We found that NFATc2– and IL-6–deficient T cells fail to induce T cell–mediated oxazolone colitis. In further mechanistic studies, we found that NFATc2 deficiency blocks IL-6 production by mucosal T lymphocytes thereby inducing T cell apoptosis and preventing development of IL-6/-13–producing T cells. Finally, we showed that activation of IL-6 signaling in vivo via hyper-IL-6 abrogates the protective effects of NFATc2 deficiency in T cell–mediated colitis and induces IL-6 and -13 production. These data identify NFATc2 as a master regulator for IL-6 production and subsequent T cell activation in experimental colitis in vivo.

Consistent with a recent proteomic study in UC (36), we observed that expression of NFATc2 proteins is increased in IBD patients. The finding that lamina propria T lymphocytes in patients with IBD expressed increased amounts of NFATc2 led us to further investigate the functional role of this transcription factor in a T cell–mediated animal model of IBD (33). These results demonstrated a potent regulatory role of NFATc2 in experimental colitis. In fact, NFATc2 KO mice were protected from oxazolone colitis, and this protective effect could be adoptively transferred by T lymphocytes, strongly suggesting that NFATc2 regulates mucosal T cell activity in vivo.

Previous studies have shown that inactivation of the NFATc2 gene leads to increased numbers of peripheral lymphocytes (23, 27, 29). This finding is at least partially caused by a defect of NFATc2-deficient splenic T cells to undergo activation-induced cell death in a Fas/FasL-dependent pathway. In contrast to these findings in peripheral T cells, we observed a significantly increased number of apoptotic mucosal CD4+ T cells in NFATc2-deficient mice in experimental colitis, suggesting that augmented T cell death in the absence of NFATc2 might contribute to protection from experimental colitis. To analyze the potential mechanism for these differences in mucosal T cell apoptosis, we next assessed the production of proinflammatory cytokines in experimental colitis. Consistent with previous studies on augmented Th2 T cell development by NFATc2-deficient T cells (27), we observed that splenic T cells from NFATc2 KO mice in oxazolone colitis produced significantly more IL-4 than T cells from WT mice. However, no significant differences in the production of this cytokine were observed between WT and NFATc2-deficient mucosal T cells, whereas IL-5 production was induced in the absence of NFATc2. In contrast, the production of IL-6, -13, and -17 was significantly reduced by NFATc2-deficient mucosal T cells compared with control WT T cells. Interestingly, IL-17 production was reduced in spite of normal or even increased levels of the Th17 master transcription factor RORγt (37–39), suggesting that both RORγt and NFATc2 are required to induce optimal IL-17 production by a large number of mucosal T cells. However, both IL-23– and IL-17A–deficient mice showed normal susceptibility for oxazolone colitis, suggesting that other cytokines might be crucial for the decreased susceptibility of NFATc2-deficient mice to oxazolone colitis.

IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine with pro- and antiinflammatory properties (40), and it stimulates target cells via a membrane receptor complex consisting of the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) and the signaling receptor subunit gp130 (41). Although gp130 is ubiquitously expressed, the IL-6R is only found on hepatocytes and some hematopoietic cells. Interestingly, a soluble form of the IL-6R (sIL-6R) has been shown to bind IL-6 and to stimulate gp130 on cells that do not express the IL-6R. This process has been named IL-6 trans-signaling (42–44) and activates T cells lacking the IL-6R such as most mucosal T cells. As IL-6 signaling has been identified as a key regulator of T cell apoptosis in experimental colitis (45–48), we have focused on the effects of IL-6 trans-signaling in NFATc2-deficient mice. It was found that the administration of hyper-IL-6, a potent activator of IL-6/sIL-6R signal transduction (44, 49), completely restores IL-13 production by NFATc2-deficient T cells and abrogates the protective effect of NFATc2 deficiency in oxazolone colitis in vivo. These data suggest that NFATc2 regulates experimental colitis in vivo in an IL-6–dependent fashion and that IL-6 signaling is important to augment mucosal IL-6 and -13 production. Finally, adoptive transfer studies showed that IL-6 production by T lymphocytes is important for activity of oxazolone-induced colitis.

NFATc2 deficiency in RAG KO mice results in the development of severe colitis (50), suggesting that this transcription factor plays a protective role in innate mucosal immune responses. In contrast, we observed here that NFATc2 plays an important pathogenic role in controlling T cell effector responses in experimental colitis. In fact, this study identifies NFATc2 as a master regulator for T cell-mediated oxazolone colitis and the regulation of IL-6 production by mucosal T cells with subsequent effects on T cell cytokine production and apoptosis. Thus, modulation of NFATc2 function in T cells appears to be an attractive target for therapeutic intervention in T cell–mediated chronic intestinal inflammation such as is observed in IBDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Gut specimens obtained from patients with CD or UC or from control patients were studied. Collection of surgical samples was approved by the ethical commitee and the institutional review board of the University of Mainz.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 7-μm cryosections from gut specimens of control and IBD patients, as previously described (18). For staining of NFATc2 transcription factor, the mouse antibodies G1-D10 or G-20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used. Immunofluorescence was performed using the tyramide signal amplification Cy3 system (PerkinElmer). Accordingly, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, followed by sequential incubation with avidin/biotin- (Vector Laboratories), peroxidase-, and protein-blocking reagent (Dako) to eliminate unspecific background staining. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies specific for human CD3 (Dianova) or NFATc2 proteins (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), dissolved in PBS/0.5% BSA/0.2% saponin. Sections incubated with isotype matched control antibodies served as negative control. Next, samples were incubated with biotinylated goat anti–rabbit secondary IgG antibody or fluorescence-conjugated antibody (Dianova) followed by incubation with streptavidin-conjugated Cy3 (Dianova) or with streptavidin-HRP and stained with tyramide-Cy3, according to the manufacturer's instructions. For confocal microscopy (Leitz Microscope) before examination, the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Vector Laboratories), mounted, and analyzed. NFATc2-positive cells in 6–10 high power fields were subsequently counted in all patients per condition.

For immunostaining of CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria, a rat anti–mouse CD4 (BD Biosciences) antibody was used. Biotinylated goat anti–rat antibodies (Dianova) and Streptavidin-Cy3 were used for subsequent analysis, as well as counterstaining with DAPI. For immunostaining of antiapoptotic proteins, rabbit-anti-bcl-xl (Cell Signaling Technology) and Armenian hamster anti-bcl-2 (BD Biosciences) antibodies were chosen. Anti–rabbit or anti–Armenian hamster biotinylated antibodies were used for subsequent staining in combination with streptavidin-HRP and tyramide-Cy3 signal amplification.

Animals.

2-4-mo-old BALB/c mice were obtained from the central breeding facility at the University of Mainz or from Charles River Laboratories; NFATc2-deficient mice have been described elsewhere (27). NFATc2-deficient mice used in the experimental studies were between 4 and 12 wk of age. CB-17/SCID mice were obtained from M&B. IL-6– and IL-13–deficient mice were previously described (51, 52). IL-23p19– and IL-17A–deficient mice were obtained from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. All animal studies were kept in specific pathogen–free conditions and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mainz.

Oxazolone-induced colitis.

Oxazolone-induced colitis in BALB/c mice was induced using a previously described method (18). After 2 d, the mice were analyzed by miniendoscopy to monitor the manifestation of colitis.

For the analysis of hyper-IL-6 (IL-6/sIL-6R fusion protein [49]) functions, mice were injected i.p. with 1 μg hyper-IL-6 (per 20 g mice weight) in 100 μl 1X PBS 1 d before sensitization and challenge with oxazolone. Control mice were injected with PBS at the same time point. In some experiments, splenic CD4+ T cells (5 × 106) from WT, NFATc2-deficient, or IL-6–deficient mice were isolated and injected into syngenic SCID mice, followed by sensitization with oxazolone. At day 7 after T cell transfer, SCID mice were challenge intrarectally with oxazolone and the body weight was monitored at indicated time points.

In vivo high resolution miniendoscopic analysis of the colon.

For monitoring of colitis activity, a high resolution video endoscopic system (Karl Storz) for mice was used (53). Prominent endoscopic signs of inflammation in CB-17/SCID mice were abrogation of the normal vascular pattern, the presence of mucosal granularity, and the appearance of ulcers. To determine colitis activity in reconstituted CB-17/SCID-deficient mice or hapten-treated mice the mice were monitored by miniendoscopy at indicated time points, and endoscopic scoring of five parameters (translucent, granularity, fibrin, vascularity, and stool) was performed.

Isolation of LPMCs.

LPMCs were isolated from freshly obtained colonic specimens using a modification of previously described techniques (54–56). LPMCs were collected at the interphase of the Percoll gradient, washed once, and resuspended in FACS buffer or cell culture medium. For some experiments, CD4+ T cells were isolated from LPMC preparations by using anti-CD4 antibodies conjugated with microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation of cytospins.

Lamina propria cells were isolated and resuspended in PBS/1% FCS at a density of 106 cells/ml in PBS. Slides were prepared in a Cytospin2-centrifuge (Shandon) and loaded with 200 μl cell suspension. After centrifugation at 500 upm for 5 min, slides were removed and dried for 2 h. Slides were subsequently stained using specific anti-bcl-xl and anti-bcl-2 antibodies, as specified above. Samples were analyzed by microscopy.

T cell culture and cytokine assays.

To measure cytokine production, 106 splenic T cells per ml were activated with 10 μg/ml purified hamster anti–mouse CD3ε (clone 145-2C11) and 5 μg/ml soluble hamster anti–mouse CD28 (clone 37.51) and cultured in complete medium or serum-free medium. LPMCs were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin or anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. Cytokine concentrations were determined by using commercially available mouse FlowCytomix systems (Bender MedSystems). For measurement of IL-6, -13, and -17F levels, commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems and Bender MedSystems) were used.

Histological analysis of colon cross sections.

Colon samples were removed from colitic mice at indicated points of time. 4 μm paraffin sections were made and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For colitis induced by oxazolone, the degree of inflammation and epithelial injury on microscopic cross sections of the colon was graded semiquantitatively from 0 to 6 (18). Grading of colitis activity was done in a blinded fashion by the same pathologist (H.A. Lehr). Small bowel sections were taken from the same animals as an additional control and showed no evidence of inflammation.

FACS analysis.

For FACS analysis, apoptotic cells were detected by staining with Annexin V antibodies, and necrotic cells were stained with 7-AAD and the cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Analysis of cell apoptosis in colonic specimens.

To visualize apoptotic cells, cryosections of colonic tissue were analyzed by TUNEL assay using a commercially available kit (Oncor-Appligene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclear staining was done with DAPI. For detection of CD3+ TUNEL+ (double-positive) cells, immunohistochemical studies were done after TUNEL staining. Blocking was done by treatment of samples with immunoblock kit (Roth) before incubation with a monoclonal antibody against CD3 (BD Biosciences). Detection was achieved using a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody against mouse IgG (Dianova).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was made using the Student's t test. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant and identified with asterisks.

Online supplemental materials.

The supplemental figures provide information on the expression of the antiapoptotic proteins bcl-2 and bcl-xl in lamina propria T cells from NFATc2-deficient mice in oxazolone-induced colitis (Fig. S1), and the IL-6, -13, and -17F production in oxazolone-induced colitis (Fig. S2). Fig. S3 demonstrates IL-6 expression during oxazolone-induced colitis in NFATc2-deficient mice, and the capacity of IL-23p19– and IL-17A–deficient mice to develop oxazolone-induced colitis (Fig. S4). The online version of this article is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20072484/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Laurie Glimcher for generously providing NFATc2 KO mice and Alexei Nikolaev for excellent work in immunohistochemistry.

The research of M.F. Neurath was supported by the MAIFOR program of the University of Mainz and the Sonderforschungsbereich SFB548 of the German Research Council (DFG). S. Rose-John was funded by the DFG within the Sonderforschungsbereich SFB415.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: AAD, amino-actinomycin D; CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LPMC, lamina propria mononuclear cell; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; UC, ulcerative colitis.

References

- 1.Bouma, G., and W. Strober. 2003. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanauer, S.B. 2006. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12:S3–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald, T.T., and G. Monteleone. 2005. Immunity, inflammation, and allergy in the gut. Science. 307:1920–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strober, W., I. Fuss, and P. Mannon. 2007. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Invest. 117:514–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breese, E., C.P. Braegger, C.J. Corrigan, J.A. Walker-Smith, and T.T. Macdonald. 1993. Interleukin-2- and interferon-gamma-secreting T cells in normal and diseased human intestinal mucosa. Immunology. 78:127–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuss, I.J., M. Neurath, M. Boirivant, J.S.Klein, C. de la Motte, S.A. Strong, C. Fiocchi, and W. Strober. 1996. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J. Immunol. 157:1261–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plevy, S.E., C.J. Landers, J. Prehn, N.M. Carramanzana, R.L. Deem, D. Shealy, and S.R. Targan. 1997. A role for TNF-alpha and mucosal T helper-1 cytokines in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. J. Immunol. 159:6276–6282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breese, E.J., C.A. Michie, S.W. Nicholls, S.H. Murch, C.B. Williams, P. Domizio, J.A. Walker-Smith, and T.T. Macdonald. 1994. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 106:1455–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrello, T., G. Monteleone, S. Cucchiara, I. Monteleone, L. Sebkova, P. Doldo, F. Luzza, and F. Pallone. 2000. Up-regulation of the IL-12 receptor beta 2 chain in Crohn's disease. J. Immunol. 165:7234–7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuoka, K., N. Inoue, T. Sato, S. Okamoto, T. Hisamatsu, Y. Kishi, A. Sakuraba, O. Hitotsumatsu, H. Ogata, K. Koganei, et al. 2004. T-bet upregulation and subsequent interleukin 12 stimulation are essential for induction of Th1 mediated immunopathology in Crohn's disease. Gut. 53:1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuss, I.J., F. Heller, M. Boirivant, F. Leon, M. Yoshida, S. Fichtner-Feigl, Z. Yang, M. Exley, A. Kitani, R.S. Blumberg, et al. 2004. Nonclassical CD1d-restricted NK T cells that produce IL-13 characterize an atypical Th2 response in ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1490–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neurath, M.F., S. Finotto, and L.H. Glimcher. 2002. The role of Th1/Th2 polarization in mucosal immunity. Nat. Med. 8:567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powrie, F., M.W. Leach, S. Mauze, S. Menon, L.B. Caddle, and R.L. Coffman. 1994. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uhlig, H.H., J. Coombes, C. Mottet, A. Izcue, C. Thompson, A. Fanger, A. Tannapfel, J.D. Fontenot, F. Ramsdell, and F. Powrie. 2006. Characterization of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ and IL-10-secreting CD4+CD25+ T cells during cure of colitis. J. Immunol. 177:5852–5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fantini, M.C., C. Becker, I. Tubbe, A. Nikolaev, H.A. Lehr, P. Galle, and M.F. Neurath. 2006. Transforming growth factor beta induced FoxP3+ regulatory T cells suppress Th1 mediated experimental colitis. Gut. 55:671–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy, K.M., and S.L. Reiner. 2002. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo, S.J., B.M. Sullivan, S.L. Peng, and L.H. Glimcher. 2003. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:713–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neurath, M.F., B. Weigmann, S. Finotto, J. Glickman, E. Nieuwenhuis, H. Iijima, A. Mizoguchi, E. Mizoguchi, J. Mudter, P.R. Galle, et al. 2002. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn's disease. J. Exp. Med. 195:1129–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirtz, S., S. Finotto, S. Kanzler, A.W. Lohse, M. Blessing, H.A. Lehr, P.R. Galle, and M.F. Neurath. 1999. Cutting edge: chronic intestinal inflammation in STAT-4 transgenic mice: characterization of disease and adoptive transfer by TNF- plus IFN-gamma-producing CD4+ T cells that respond to bacterial antigens. J. Immunol. 162:1884–1888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroud, J.C., C. Lopez-Rodriguez, A. Rao, and L. Chen. 2002. Structure of a TonEBP-DNA complex reveals DNA encircled by a transcription factor. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez-Rodriguez, C., J. Aramburu, A.S. Rakeman, and A. Rao. 1999. NFAT5, a constitutively nuclear NFAT protein that does not cooperate with Fos and Jun. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:7214–7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng, S.L., A.J. Gerth, A.M. Ranger, and L.H. Glimcher. 2001. NFATc1 and NFATc2 together control both T and B cell activation and differentiation. Immunity. 14:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao, A., C. Luo, and P.G. Hogan. 1997. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:707–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serfling, E., F. Berberich-Siebelt, S. Chuvpilo, E. Jankevics, S. Klein-Hessling, T. Twardzik, and A. Avots. 2000. The role of NF-AT transcription factors in T cell activation and differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1498:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crabtree, G.R., and E.N. Olson. 2002. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 109(Suppl):S67–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuvpilo, S., E. Jankevics, D. Tyrsin, A. Akimzhanov, D. Moroz, M.K. Jha, J. Schulze-Luehrmann, B. Santner-Nanan, E. Feoktistova, T. Konig, et al. 2002. Autoregulation of NFATc1/A expression facilitates effector T cells to escape from rapid apoptosis. Immunity. 16:881–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodge, M.R., A.M. Ranger, F. Charles de la Brousse, T. Hoey, M.J. Grusby, and L.H. Glimcher. 1996. Hyperproliferation and dysregulation of IL-4 expression in NF-ATp-deficient mice. Immunity. 4:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xanthoudakis, S., J.P. Viola, K.T. Shaw, C. Luo, J.D. Wallace, P.T. Bozza, D.C. Luk, T. Curran, and A. Rao. 1996. An enhanced immune response in mice lacking the transcription factor NFAT1. Science. 272:892–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rengarajan, J., P.R. Mittelstadt, H.W. Mages, A.J. Gerth, R.A. Kroczek, J.D. Ashwell, and L.H. Glimcher. 2000. Sequential involvement of NFAT and Egr transcription factors in FasL regulation. Immunity. 12:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rengarajan, J., B. Tang, and L.H. Glimcher. 2002. NFATc2 and NFATc3 regulate T(H)2 differentiation and modulate TCR-responsiveness of naive T(H)cells. Nat. Immunol. 3:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiani, A., F.J. Garcia-Cozar, I. Habermann, S. Laforsch, T. Aebischer, G. Ehninger, and A. Rao. 2001. Regulation of interferon-gamma gene expression by nuclear factor of activated T cells. Blood. 98:1480–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta, D.S., A.L. Wurster, A.S. Weinmann, and M.J. Grusby. 2005. NFATc2 and T-bet contribute to T-helper-cell-subset-specific regulation of IL-21 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:2016–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boirivant, M., I.J. Fuss, A. Chu, and W. Strober. 1998. Oxazolone colitis: a murine model of T helper cell type 2 colitis treatable with antibodies to interleukin 4. J. Exp. Med. 188:1929–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heller, F., I.J. Fuss, E.E. Nieuwenhuis, R.S. Blumberg, and W. Strober. 2002. Oxazolone colitis, a Th2 colitis model resembling ulcerative colitis, is mediated by IL-13-producing NK-T cells. Immunity. 17:629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizarro, T.T., and F. Cominelli. 2007. Cytokine therapy for Crohn's disease: advances in translational research. Annu. Rev. Med. 58:433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsieh, S.Y., T.C. Shih, C.Y. Yeh, C.J. Lin, Y.Y. Chou, and Y.S. Lee. 2006. Comparative proteomic studies on the pathogenesis of human ulcerative colitis. Proteomics. 6:5322–5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivanov, I.I., B.S. McKenzie, L. Zhou, C.E. Tadokoro, A. Lepelley, J.J. Lafaille, D.J. Cua, and D.R. Littman. 2006. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 126:1121–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He, Y.W., M.L. Deftos, E.W. Ojala, and M.J. Bevan. 1998. RORgamma t, a novel isoform of an orphan receptor, negatively regulates Fas ligand expression and IL-2 production in T cells. Immunity. 9:797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Littman, D.R., Z. Sun, D. Unutmaz, M.J. Sunshine, H.T. Petrie, and Y.R. Zou. 1999. Role of the nuclear hormone receptor ROR gamma in transcriptional regulation, thymocyte survival, and lymphoid organogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 64:373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimoto, N., and T. Kishimoto. 2006. Interleukin 6: from bench to bedside. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taga, T., and T. Kishimoto. 1997. Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:797–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, Q., D.T. Fisher, K.A. Clancy, J.M. Gauguet, W.C. Wang, E. Unger, S. Rose-John, U.H. von Andrian, H. Baumann, and S.S. Evans. 2006. Fever-range thermal stress promotes lymphocyte trafficking across high endothelial venules via an interleukin 6 trans-signaling mechanism. Nat. Immunol. 7:1299–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones, S.A., P.J. Richards, J. Scheller, and S. Rose-John. 2005. IL-6 transsignaling: the in vivo consequences. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer, M., J. Goldschmitt, C. Peschel, J.P. Brakenhoff, K.J. Kallen, A. Wollmer, J. Grotzinger, and S. Rose-John. 1997. I. A bioactive designer cytokine for human hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:142–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atreya, R., J. Mudter, S. Finotto, J. Mullberg, T. Jostock, S. Wirtz, M. Schutz, B. Bartsch, M. Holtmann, C. Becker, et al. 2000. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat. Med. 6:583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kai, Y., I. Takahashi, H. Ishikawa, T. Hiroi, T. Mizushima, C. Matsuda, D. Kishi, H. Hamada, H. Tamagawa, T. Ito, et al. 2005. Colitis in mice lacking the common cytokine receptor gamma chain is mediated by IL-6-producing CD4+ T cells. Gastroenterology. 128:922–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto, M., K. Yoshizaki, T. Kishimoto, and H. Ito. 2000. IL-6 is required for the development of Th1 cell-mediated murine colitis. J. Immunol. 164:4878–4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neurath, M.F., S. Finotto, I. Fuss, M. Boirivant, P.R. Galle, and W. Strober. 2001. Regulation of T-cell apoptosis in inflammatory bowel disease: to die or not to die, that is the mucosal question. Trends Immunol. 22:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peters, M., G. Blinn, T. Jostock, P. Schirmacher, K.H. Meyer zum Buschenfelde, P.R. Galle, and S. Rose-John. 2000. Combined interleukin 6 and soluble interleukin 6 receptor accelerates murine liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 119:1663–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerth, A.J., L. Lin, M.F. Neurath, L.H. Glimcher, and S.L. Peng. 2004. An innate cell-mediated, murine ulcerative colitis-like syndrome in the absence of nuclear factor of activated T cells. Gastroenterology. 126:1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kopf, M., H. Baumann, G. Freer, M. Freudenberg, M. Lamers, T. Kishimoto, R. Zinkernagel, H. Bluethmann, and G. Kohler. 1994. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 368:339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKenzie, G.J., C.L. Emson, S.E. Bell, S. Anderson, P. Fallon, G. Zurawski, R. Murray, R. Grencis, and A.N. McKenzie. 1998. Impaired development of Th2 cells in IL-13-deficient mice. Immunity. 9:423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Becker, C., M.C. Fantini, S. Wirtz, A. Nikolaev, R. Kiesslich, H.A. Lehr, P.R. Galle, and M.F. Neurath. 2005. In vivo imaging of colitis and colon cancer development in mice using high resolution chromoendoscopy. Gut. 54:950–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neurath, M.F., I. Fuss, B.L. Kelsall, E. Stuber, and W. Strober. 1995. Antibodies to interleukin 12 abrogate established experimental colitis in mice. J. Exp. Med. 182:1281–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van der Heijden, P.J., and W. Stok. 1987. Improved procedure for the isolation of functionally active lymphoid cells from the murine intestine. J. Immunol. Methods. 103:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weigmann, B., I. Tubbe, D. Seidel, A. Nicolaev, C. Becker, and M.F. Neurath. 2007. Isolation and subsequent analysis of murine lamina propria mononuclear cells from colonic tissue. Nat. Protocols. 2:2307–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.