Abstract

Summary: BioJava is a mature open-source project that provides a framework for processing of biological data. BioJava contains powerful analysis and statistical routines, tools for parsing common file formats and packages for manipulating sequences and 3D structures. It enables rapid bioinformatics application development in the Java programming language.

Availability: BioJava is an open-source project distributed under the Lesser GPL (LGPL). BioJava can be downloaded from the BioJava website (http://www.biojava.org). BioJava requires Java 1.5 or higher.

Contact: andreas.prlic@gmail.com. All queries should be directed to the BioJava mailing lists. Details are available at http://biojava.org/wiki/BioJava:MailingLists.

1 INTRODUCTION

BioJava was conceived in 1999 by Thomas Down and Matthew Pocock as an Application Programming Interface (API) to simplify bioinformatics software development using Java (Pocock, 2003; Pocock et al., 2000). It has since then evolved to become a fully featured framework with modules for performing many common bioinformatics tasks. The goal of BioJava is to facilitate code reuse and to provide standard implementations that are easy to link to external scripts and applications.

BioJava is an open-source project that is developed by volunteers and coordinated by the Open Bioinformatics Foundation (OBF). It is one of several Bio* toolkits (Mangalam, 2002). All code is distributed under the LGPL license and can be freely used and reused in any form.

BioJava is a mature project and has been employed in a number of real-world applications and over 50 published studies. A list of these can be found on the BioJava website. According to the project tracking web site Ohloh (http://www.ohloh.net/projects/biojava), the BioJava code-base represents an estimated 47 person-years worth of effort.

2 FEATURES

BioJava contains a number of mature APIs. The 10 most frequently used are: (1) nucleotide and amino acid alphabets, (2) BLAST parser, (3) sequence I/O, (4) dynamic programming, (5) structure I/O and manipulation, (6) sequence manipulation, (7) genetic algorithms, (8) statistical distributions, (9) graphical user interfaces and (10) serialization to databases. Below follows a short discussion of some of these modules.

At the core of BioJava is a symbolic alphabet API which represents sequences as a list of references to singleton symbol objects that are derived from an alphabet. Lists of symbols are stored whenever possible in a compressed form of up to four symbols per byte of memory.

In addition to the fundamental symbols of a given alphabet (A, C, G and T in the case of DNA), all BioJava alphabets implicitly contain extra symbol objects representing all possible combinations of the fundamental symbols.

The symbol approach allows the construction of higher order alphabets and symbols that represent the multiplication of one or more alphabets. An example is the codon ‘alphabet’ which is the cubed product of the DNA alphabet, each codon ‘symbol’ comprising three DNA symbols. Such an alphabet allows construction of views over sequences without modifying the underlying sequence which is useful for tasks such as translation. Other complex alphabets which can be described include conditional alphabets for the construction of conditional probability distributions, and heterogeneous alphabets such as the combination of the codon and protein alphabets for use with a DNA–protein aligning hidden Markov model (HMM). Other interesting applications of the alphabet API include chromosomes for genetic algorithms using, but not limited to, integer or binary symbol lists, and the representation of Phred quality scores (Ewing et al., 1998) as a multiplication of the DNA and integer alphabets.

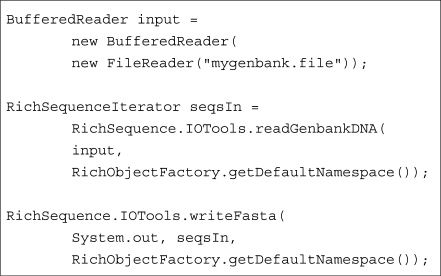

The typical user would most likely start out by using the sequence input/output API and the sequence/feature object model. These allow sequences to be loaded from a number of common file formats such as FASTA, GenBank and EMBL, optionally manipulated in memory, then saved again or converted into a different format. The simplicity of this process is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Loading a GenBank file with BioJava and writing it out as FASTA. The example demonstrates the use of several convenience methods that hide the bulk of the implementation. If the developer desires a more flexible parser it is possible to make use of the interfaces hidden behind the convenience methods to expose a fully customizable, multi-component, event-based parsing model.

Another useful API is the feature/annotation object model which associates sequences with located features and unlocated annotations. Features can be found either by keyword or by defining a location query from which all overlapping or contained features are returned, while annotations can be retrieved by keyword. The location model handles circular and stranded locations, split locations and multi-sequence locations allowing features to span complex sets of coordinates.

The protein structure API contains tools for parsing and manipulating PDB files (Berman et al., 2000). It contains utility methods to perform linear algebra calculations on atomic coordinates and can calculate 3D structure alignments. A simple interface to the 3D visualization library Jmol (http://www.jmol.org) is contained as well. An add-on allows the serialization of the content of a PDB file to a database using Hibernate (http://www.hibernate.org).

Other APIs include those for working with chromatograms, sequence alignments, proteomics and ontologies. Parsers are provided for reading, amongst others, Blast reports (Altschul et al., 1997), ABI chromatograms and NCBI taxonomy definitions.

Recently the BioJavaX module was added which provides more detailed parsing of the common file formats and improved storing of sequence data into BioSQL databases (http://www.biosql.org). This allows to incorporate BioJava into existing data processing pipelines which use alternative OBF toolkits such as BioPerl (Stajich et al., 2002).

The BioJava web site provides detailed manuals on how to use the different components. In particular, the ‘CookBook’ section provides a quick introduction into solving many problems by demonstrating solutions with documented source code. There is also a section to demonstrate the performance of a few selected tasks via Java WebStart examples. To mention just one: the FASTA-formatted release 4 Drosophila genome sequence can be parsed in <20 s on a 1.80 GHz Core Duo processor.

3 FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

BioJava aims to provide an API that is of use to anyone using Java to develop bioinformatics software, regardless of which specialization they may work in. Genomic features currently must be manipulated with reference to the underlying genomic sequence, which can make working with post-genomic datasets, such as microarray results, overly complex. Phylogenetics tools are already in development which will allow users to work with NEXUS tree files (Maddison et al., 1997).

Although the Blast parsing API is widely used, it does not support all of the existing blast-family output formats. We will continue the ongoing effort to add parsers for PSI-Blast and other currently unsupported formats.

Users are welcome to identify further areas of need and their suggestions will be incorporated into future developments.

BioJava is written entirely in the Java programming language, and will run on any platform for which a Java 1.5 run-time environment is available. Java 5 and 6 provide advanced language features, and we shall be taking advantage of these in the next major release, both to aid in maintenance of the library and to make it even easier for novice Java developers to make use of the BioJava APIs.

4 CONCLUSIONS

BioJava is one of the largest open-source APIs for bioinformatics software development. It is a mature project with a large user and support community. It offers a wide range of tools for common bioinformatics tasks. The BioJava homepage provides access to the source code and detailed documentation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank everybody who made code or documentation contribution during the project's life. Each of these contribution is appreciated, though the total list of contributors is too long to be reproduced here. BioJava is not formally funded by any grants. Through the OBF we have received sponsorship from Sun Microsystems, Apple Computers and NESCent. The initial development of the phylogenetics module was undertaken as a Google Summer of Code 2007 project in collaboration with NESCent.

Funding: Funding for open access charge: Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock M. PhD thesis. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge; 2003. Computational analysis of genomes. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock M, et al. BioJava: open source components for bioinformatics. ACM SIGBIO Newsl. 2000;20:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, et al. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison DR, et al. NEXUS: an extensible file format for systematic information. Syst. Biol. 1997;46:590–621. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/46.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangalam H. The Bio* toolkits - a brief overview. Brief. Bioinform. 2002;3:396–302. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich JE, et al. The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res. 2002;12:1611–1618. doi: 10.1101/gr.361602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]