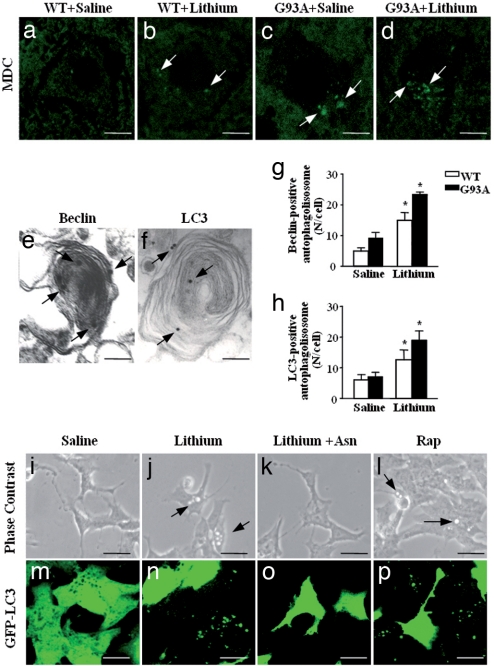

Fig. 4.

Effects of lithium on autophagy in vivo and in vitro. (a–d) MDC-positive small vacuoles in the lumbar spinal cord of WT (a and c, arrows) and G93A mice (b and d, arrows). (e) Representative picture of beclin immunostained vacuoles in the cytoplasm of alpha MN from a G93A lithium-treated mouse. The ImmunoGold particles (20 nm) are localized on both the membrane (that surround the core) and the electrondense core (arrows). (f) LC3 immunostaining is present on a larger membranous structure; the ImmunoGold particles (20 nm) are randomly localized (arrows). (g) The count of beclin immunostained structures shows a marked effect of lithium in MN both WT and G93A mice. (h) Likewise, LC3 immunopositive vacuoles increase significantly in G93A and WT mice administered lithium. (i–l) Phase-contrast microscopic images of lithium-induced accumulation of vacuoles in SH-SY5Y cells exposed or not for 72 h to 1 mM lithium (j), or lithium plus 50 mM asparagine (Asn) (a slight autophagy blocker acting downstream of lithium) (k), or 400 nM rapamycin (Rap) (l). Arrows point to cytoplasmic vacuoles that accumulate in cells treated with lithium or Rap (a known autophagy inducer). No vacuolization was observed in control (i) or lithium plus Asn-treated cells. (m–p) A parallel experiment was performed with transfected SH-SY5Y cells stably expressing the GFP-LC3 chimeric fluorescent protein. The images clearly show that both lithium (n) and rapamycin (p) change the cytoplasmic diffuse fluorescence pattern of GFP-LC3 to a punctuated pattern indicative of autophagosome formation. Asparagine (o) inhibited the effect of lithium on GFP-LC3 localization. *, P < 0.05 compared with saline. (Scale bars: a–d, 14 μm; e, 0.1 μm; f, 0.08 μm; i–l, 20 μm; m–p, 50 μm.)