Abstract

In the renal collecting duct, vasopressin controls transport of water and solutes via regulation of membrane transporters such as aquaporin-2 (AQP2) and the epithelial urea transporter UT-A. To discover proteins potentially involved in vasopressin action in rat kidney collecting ducts, we enriched membrane “raft” proteins by harvesting detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) of the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells. Proteins were identified and quantified with LC-MS/MS. A total of 814 proteins were identified in the DRM fractions. Of these, 186, including several characteristic raft proteins, were enriched in the DRMs. Immunoblotting confirmed DRM enrichment of representative proteins. Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of rat IMCDs with antibodies to DRM proteins demonstrated heterogeneity of raft subdomains: MAL2 (apical region), RalA (predominant basolateral labeling), caveolin-2 (punctate labeling distributed throughout the cells), and flotillin-1 (discrete labeling of large intracellular structures). The DRM proteome included GPI-anchored, doubly acylated, singly acylated, cholesterol-binding, and integral membrane proteins (IMPs). The IMPs were, on average, much smaller and more hydrophobic than IMPs identified in non-DRM-enriched IMCD. The content of serine 256-phosphorylated AQP2 was greater in DRM than in non-DRM fractions. Vasopressin did not change the DRM-to-non-DRM ratio of most proteins, whether quantified by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS, n = 22) or immunoblotting (n = 6). However, Rab7 and annexin-2 showed small increases in the DRM fraction in response to vasopressin. In accord with the long-term goal of creating a systems-level analysis of transport regulation, this study has identified a large number of membrane-associated proteins expressed in the IMCD that have potential roles in vasopressin action.

Keywords: aquaporin-2, vasopressin, membrane rafts, mass spectrometry, proteomics

the collecting duct is the terminal part of the renal tubule. Its major function is regulated transport of water and solutes. The antidiuretic peptide hormone vasopressin is one of the key regulatory factors. Vasopressin increases renal water reabsorption, in part, by increasing the number of aquaporin (AQP)-2 (AQP2) water channels in the apical plasma membrane of renal collecting duct cells. This is accomplished by regulation of trafficking of AQP2-containing vesicles to and from the apical plasma membrane. Abnormalities in this process are responsible for several clinically important disorders of water balance (22, 37). Similar mechanisms may be involved in regulation of the urea transporters UT-A1 and UT-A3 in the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) (13).

Membrane rafts are defined as small (10–200 nm), highly dynamic, heterogeneous, sterol- and sphingolipid-enriched membrane microdomains (45, 49). They undergo rapid assembly and disassembly and are believed to cluster together to function as a platform for membrane signaling and trafficking. Certain types of proteins, including GPI-anchored proteins, heterotrimeric G protein α-subunits, dually acylated proteins such as Src tyrosine kinases, palmitoylated and myristoylated proteins such as flotillins, cholesterol-binding proteins such as caveolins, and phospholipid-binding proteins such as annexins, have been reported to segregate into membrane rafts (49). Such proteins can be identified in detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fractions, because raftlike domains are not fully solubilized by nonionic detergents such as Triton X-100 at low temperature and remain buoyant in density gradient centrifugation. An important goal in a systems-level analysis of AQP2 regulation is identification of proteins in collecting duct cells, including membrane raft proteins, which have the potential to play roles in transport regulation. A key tool in this endeavor is tandem mass spectrometry [LC-MS/MS, i.e., liquid chromatography (LC)-mass spectrometry (MS)], which has the potential to identify and quantify large numbers of proteins in biochemically prepared samples. Previously, we used LC-MS/MS to identify proteins in AQP2-containing vesicles (1) and in apical and basolateral plasma membranes isolated via surface biotinylation (59).

DRMs prepared with nonionic detergent extraction and discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation are not generally identical to membrane rafts because proteins may be lost or added during purification of DRMs (4). Nevertheless, isolation of DRMs can enrich proteins normally present in membrane rafts that may otherwise be difficult to detect by LC-MS/MS of whole membrane fractions. As a step to understand apical trafficking of AQP2, we have used LC-MS/MS to analyze the proteome of DRMs isolated from AQP2-expressing IMCD cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Pathogen-free male Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) were maintained on ad libitum rat chow (NIH-07, Zeigler, Gardners, PA) and drinking water in the Small Animal Facility at the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. Animal experiments were conducted under the auspices of Animal Protocol H-0110 approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

IMCD cell suspension.

Detailed procedures for preparation of IMCD cell suspensions have been described previously (8). Briefly, 20 adult rats (200–250 g body wt) were treated with furosemide (5 mg/rat ip for 20 min), which dissipates the medullary osmolality, thereby preventing osmotic shock to the cells on isolation of the inner medullas (52). The animals were killed by decapitation, and both inner medullas were excised from the kidneys. The inner medullas were minced into ∼1-mm cubes and digested with 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase and 3 mg/ml collagenase B in 4 ml of isolation solution [250 mM sucrose and 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)] at 37°C for 90 min. The samples were subjected to centrifugation at 60 g for 20 s to gently sediment the heavier IMCD segments from the non-IMCD components of the inner medulla (loops of Henle, interstitial cells, vasa recta, and capillaries). The sedimented IMCD segments were washed three times in 4 ml of ice-cold isolation solution and centrifuged as described above. Microscopic examination was carried out to confirm that the resulting suspensions contain mostly IMCD cells (>90% of total cells). The IMCD cells were finally suspended in 2 ml of ice-cold HEPES-buffered saline solution (in mM: 162.5 NaCl, 25 HEPES, 4 KCl, 2.5 Na2HPO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, and 5.5 glucose) before treatment with the vasopressin analog [deamino-Cys1,d-Arg8]vasopressin (dDAVP).

DRM preparation.

A modification of the methods of Brown and Rose (5) and Foster et al. (15), which uses the nonionic detergent Triton X-100 and discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation, was used for preparation of IMCD DRMs. All the procedures described below were carried out at 4°C. TNE buffer (in mM: 25 Tris, 150 NaCl, and 5 EDTA) was supplied with protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog no. 11836153001, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) at one tablet per 10 ml of solution. For preparation of IMCD DRMs, IMCD cells were pelleted by brief centrifugation at 60 g. HEPES-buffered saline solution was removed, and the IMCD cell pellet was solubilized in 2 ml of 1% Triton X-100 in TNE buffer for 3 h with rotary motion. An equal volume of 80% (wt/vol) sucrose in TNE buffer was then added to the solubilized IMCD to make a final 40% sucrose solution, which was placed at the bottom of a centrifuge tube (catalog no. 331372, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). On the top of the 40% sucrose solution, 4 ml of 35% sucrose solution in TNE buffer were overlaid, followed by 4 ml of 5% sucrose solution in TNE solution. Ultracentrifugation was carried out using a swing-bucket rotor (model SW41 Ti, Beckman Coulter) at 39,000 rpm (188,000 g) for 20 h. Between 10 and 17 fractions were collected from the top to the bottom of the centrifuge tube and stored at −20°C.

dDAVP treatment.

For quantitative proteomic comparison between vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells, an IMCD cell suspension obtained from 20 rats was divided into two parts, 1 ml each for vehicle and dDAVP treatment. The IMCD cell suspensions were warmed to 37°C for 30 min, and 1 ml of prewarmed HEPES-buffered saline solution containing 0 or 2 nM dDAVP (1 nM final dDAVP concentration) was added to the suspensions. The IMCD cell suspensions were incubated for 20 min and then stored on ice, moved to a cold (4°C) room, and used for the membrane raft preparation. The above-described experiment was repeated three times to obtain enough protein from 60 rats for quantitative LC-MS/MS. Samples from each experiment were analyzed and stored separately. They were pooled only before LC-MS/MS protein identification.

Immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting was carried out as previously described (12). After solubilization in Laemmli's reagent, 10–15 μl of each fraction were resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide minigel and transferred electrophoretically onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in blot washing buffer (in mM: 42 Na2HPO4, 8 NaH2PO4, and 150 NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 7.5), washed with the blot washing buffer, and then incubated with a primary antibody diluted in a blocking buffer (catalog no. 927-40000, Li-Cor Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE) overnight at room temperature. After it was washed, the membrane was incubated with species-specific secondary antibody conjugated to fluorescent IRDye diluted in the blocking buffer. The membrane was washed, and antibody binding was visualized using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Biotechnology).

The antibody against the Na+- and Cl−-dependent taurine transporter (TauT) was a gift from Russell Chesney (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN). The antibodies against myosin IIA and IIB were provided by Robert S. Adelstein (NHLBI) (44). The antiserum against myosin VB was provided by John A. Hammer (NHLBI). The antibody against phosphorylated AQP2 at serine 256 has been previously characterized (41). The antibodies against AQP1 (55), AQP2 (1), MAL/vesicular integral protein 17 (VIP17) (30), Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC2) (26), SNAP23 (21), UT-A1 (40), and vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-2 (28) were raised in our laboratories. The rabbit polyclonal antibody against MAL-2 was raised against a synthetic peptide, NPAVSFPAPRITLPAG, conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Similarly, the rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Na+-K+-ATPase α1-subunit were raised against keyhole limpet hemocyanin-conjugated synthetic peptides against CDEVRKLIIRRRPGGWVEKETYY. The commercial antibodies against caveolin-1 (catalog no. 610406), caveolin-2 (catalog no. 610684), E-cadherin (catalog no. 610181), flotillin-1 (catalog no. 610820), flotillin-2 (catalog no. 610384), Rab11 (catalog no. 610656), and RalA (catalog no. 610221) were obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA); antibodies against annexin A2 (catalog no. sc-1924), annexin A4 (catalo6g no. sc-1930), Gαi3 (catalog no. sc-262), Gαs (catalog no. sc-823), Gβ1 (catalog no. sc-379), Gβ2 (catalog no. sc-380), Rab5b (catalog no. sc-598), and Rap1 (catalog no. sc-65) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); antibodies against β-actin (catalog no. 4967) and myosin light chain 2 (catalog no. 3672) from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); antibodies against myosin IC (catalog no. M3567) and ezrin (catalog no. E1281) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); antibodies against calnexin (catalog no. SPA-860), Sec6 (catalog no. VAM-SV021), and Sec8 (catalog no. VAM-SV016) from Stressgen Bioreagents (Ann Arbor, MI); antibody against Src (catalog no. 05-184) from Millipore (Charlottesville, VA); antibody against syntaxin 7 (catalog no. 110 072) from Synaptic Systems (Goettingen, Germany); and species-specific secondary antibodies from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA).

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

Techniques for indirect immunofluorescence staining of kidney sections were described previously (59). Confocal fluorescence images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope and software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) at the Light Microscopic Facility in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Preparation of proteins for mass spectrometric identification.

Proteins in the membrane raft fraction (fraction 5) were concentrated using 10,000-Da cutoff Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Devices (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and separated on a 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE minigel (Bio-Rad Life Science, Hercules, CA). The gel was stained with Coomassie blue (GelCode, Pierce Biotechnology) for visualization of the proteins, and the entire sample lane was cut into 16 sequential ∼2-mm-thick slices. Proteins in each gel slice were destained, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin using a previously described protocol (46) before LC-MS/MS protein identification.

LC-MS/MS protein identification and analysis.

Tryptic peptides extracted from each gel slice were injected into a reverse-phase LC column (PicoFrit, Biobasic C18, New Objective, Woodburn, MA) to stratify sample proteins before delivery to an LTQ tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS, Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) via a nanoelectrospray ion source. The spectra with a total ion current >10,000 were used to search for matches to peptides in a concatenated RefSeq database using Bioworks software (version 3.1, Thermo Electron) based on the Sequest algorithm. The concatenated RefSeq database is composed of forward protein sequences (24,096 entries) and reverse protein sequences (24,096 entries) derived from the National Center for Biotechnology Information on 6 June 2006 using in-house software. The search parameters included 1) precursor ion mass tolerance <2 atomic mass units (amu), 2) fragment ion mass tolerance <1 amu, 3) as many as three missed tryptic cleavages, and 4) amino acid modifications as follows: cysteine carboxyamidomethylation (plus 57.05 amu) and methionine oxidation (plus 15.99 amu).

For protein identifications, in-house software was used to filter the matched peptide sequences using the following initial settings: 1) ranks of the primary scores <10, 2) ranks of the cross-correlation (Xcorr) scores = 1, 3) Xcorr scores >1.3, 1.8, and 2.3 for charged states 1, 2, and 3 peptide ions, respectively, and 4) uniqueness scores of matches >0.1. The software then used probability-based target-decoy analysis to minimize false-positive protein identification (2). Peptide matches to the reverse sequences were considered random and were used to calculate a random peptide match rate, which was defined as the number of peptide matches to the reverse sequences divided by the total number of peptide matches. The rate of false-positive peptide matches to the forward sequences was assumed to be the same as the rate of random peptide matches. The software then elevated the Xcorr score of each charge state by 0.1 units and calculated a new false-positive peptide match rate until the false-positive peptide match rate reached 2.5%. The false-positive protein identification rate was calculated as follows: [false-positive peptide match rate/(1 − random peptide match rate)]n, where n is the number of peptides identified for that protein.

Data repository.

Raw mass spectrometric raw data are deposited in the Tranche repository to facilitate data sharing and validation. To retrieve the raw data, run a JAVA program at this link, http://www.proteomecommons.org/dev/dfs/GetFileTool.jnlp, and provide the hash, Qk/MRVLDN73LgtKO56wrmZbvA4ZyCe4LUmqr/WfELDDoEIgi4uAQ/mGfjgx8exsLzKkqDabsFsrhQRoJwiDUyfxtHSQAAAAAAAAtTg==.

Quantification and statistics.

Label-free quantitative analysis of protein abundance was performed using QUOIL software (58), which calculated the ratios of the areas of the reconstructed peptide LC elution profiles from two samples. The peptide mass tolerance was set to 1.1 Da. The minimal signal-to-noise threshold was set at 1.5-fold. Noise was subtracted from the calculation of relative peptide abundance. To determine whether a protein was more abundant in one sample than in another other, we used the two-tailed Student's t-test to test whether the mean base 2 logarithmic (log2) values of the ratios of the areas of all peptide elution profiles of the same protein are different from zero. Proteins that passed the t-test with positive mean log2 values were considered more abundant in one sample, whereas proteins that passed the t-test with negative mean log2 values were considered more abundant in the other sample. Proteins that did not pass the t-test were considered indeterminant with regard to their relative abundance in samples. It is likely that they were relatively abundant in both samples.

The IMCD accounts for only a small fraction of the whole kidney, and DRM proteins are only a small fraction of IMCD proteins. Therefore, a large number of animals were needed to obtain sufficient DRM protein for mass spectrometry. To initially characterize the DRM fraction, we used 20 rats. To compare proteomes of vehicle- and dDAVP-treated DRMs, we pooled 3 DRM preparations from 60 rats (see above). The use of so many rats per sample has the advantage of buffering the effect of biological variability. Finally, to account for analytic variation by the QUOIL software, we validated the quantification results by immunoblotting.

Bioinformatics and statistics.

Protein information was retrieved from the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt; http://www.expasy.uniprot.org) using the Batch Retrieval function from the Protein Information Resource (PIR) website (http://pir.georgetown.edu). Cellular component gene ontology (GO) terms were extracted directly from the National Center for Biotechnology Information protein database using in-house software. A χ2 test was performed to determine whether one protein population displayed a given protein characteristic (i.e., a GO term) more frequently than the other protein population. The χ2 test was done using InStat software (version 3.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

IMCD DRM preparation.

Nonionic detergent extraction and discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation were combined to isolate DRMs from freshly isolated rat kidney IMCD cells. As shown in Fig. 1, the IMCD DRM fraction was observed as a white band at the junction between 5% and 35% sucrose solutions (15). Seventeen fractions were collected from the top to the bottom of the centrifugation tube. Protein concentration measurements indicated that only a relatively small amount of the total protein was present in the DRM fractions (Fig. 1, middle, fractions 5–7). For immunoblotting, equal volumes of each fraction were loaded to provide an initial characterization of these fractions (Fig. 1, bottom). Known membrane raft markers, MAL/VIP17 and flotillin-1, were most abundant in the DRM fractions (fractions 5–7). Some integral membrane proteins were found chiefly in the non-DRM fractions (fractions 13–17), including calnexin, Na+-K+-ATPase α1-subunit, and TauT. The vasopressin-regulated water channel AQP2 was found in DRM and non-DRM fractions in approximately equal amounts. The DRM preparation shown in Fig. 1 was used for LC-MS/MS proteomic analysis.

Fig. 1.

Preparation and characterization of inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fractions. Kidneys from 20 adult Sprague-Dawley rats were used to prepare the IMCD cell suspension and, subsequently, DRM fractions by Triton X-100 detergent extraction and discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation. IMCD DRM fractions were located at the junction between 5% and 35% sucrose solutions, reflecting an indoor fluorescent lamp illumination with a dark background (15). Seventeen fractions (1–17) were collected from the top to the bottom of the centrifuge tube. A 10-μl protein sample from each fraction was used for immunoblot analysis. DRM fractions (fractions 5–7) were enriched with membrane raft marker proteins (flotillin-1 and MAL/VIP17) and deenriched of some integral membrane proteins [calnexin, Na+-K+-ATPase α1-subunit, and Na+- and Cl−-dependent taurine transporter (TauT)].

LC-MS/MS analysis of IMCD DRM of untreated IMCD cells.

One hundred micrograms of protein from the DRM fraction (fraction 5 in Fig. 1) were separated on a 4–15% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel. (See supplemental Fig. S1 in the online version of this article, which shows the gel stained with Coomassie blue to indicate how the gel was cut into 16 gel slices before protein identification in each slice by LC-MS/MS.) An equal amount of protein from a non-DRM fraction (fraction 14) was prepared in parallel for quantitative analysis. Protein identifications were subjected to a probability-based target-decoy assessment to effectively reduce false-positive identifications to ∼2.5% (see materials and methods). Table 1 shows the computational assessment of the protein identifications from the DRM and non-DRM fractions. Four hundred eleven proteins in the DRM fraction were identified by a single peptide match with a predicted false-positive rate of 2.6%. The predicted false-positive protein identification rates decrease exponentially as the number of peptides identified for particular proteins increases. Four hundred three proteins were identified in the DRM fraction on the basis of two or more peptides with false-positive rates <0.1%. Overall, a total of 814 proteins were identified in the DRM fraction and 1,212 proteins were identified in the non-DRM fraction with the indicated filters (Table 1). [See supplemental Tables S1 (fraction 5, DRM fraction) and S2 (fraction 14, non-DRM fraction) for a list of these protein identifications with their identified peptide sequences and associated statistical scores. Also, see supplemental Figs. S2 and S3 for spectra of single-peptide identifications, along with their observed precursor mass-to-charge ratios (m/z).]

Table 1.

Probability-based target-decoy analysis of protein identifications in DRM and non-DRM fractions of IMCD cells

| No. of Peptides | No. of Proteins | False Positive, % |

|---|---|---|

| DRM fraction (fraction 5) | ||

| 1 | 411 | 2.554 |

| 2 | 112 | 0.065 |

| 3 | 73 | 0.002 |

| >3 | 218 | ∼0 |

| Total | 814 | |

| Non-DRM fraction (fraction 14) | ||

| 1 | 607 | 2.543 |

| 2 | 178 | 0.065 |

| 3 | 91 | 0.002 |

| >3 | 336 | ∼0 |

| Total | 1,212 | |

Mass spectra were used to search against a concatenated protein database composed of forward and reverse rat RefSeq protein sequences from the National Center of Biotechnology Information. Rate of spectrum matches to reverse sequences was used to estimate rate of false-positive matches to forward sequences. Filter settings to reach false-positive protein identification rates are as follows: ranks of the primary scores (Rsp) < 10, cross-correlation (XCorr) rank: 1, uniqueness score of matches (ΔCn) > 0.1, Xcorr score = 1.89 for charged state 1 peptide ions (+1), 2.39 for charge state 2 peptide ions (+2), and 2.89 for charge state 3 peptide ions (+3) for detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fraction and Rsp < 10, Xcorr rank: 1, ΔCn > 0.1, Xcorr score = 1.75 (+1), 2.25 (+2), and 2.75 (+3) for non-DRM fraction. IMCD, inner medullary collecting duct.

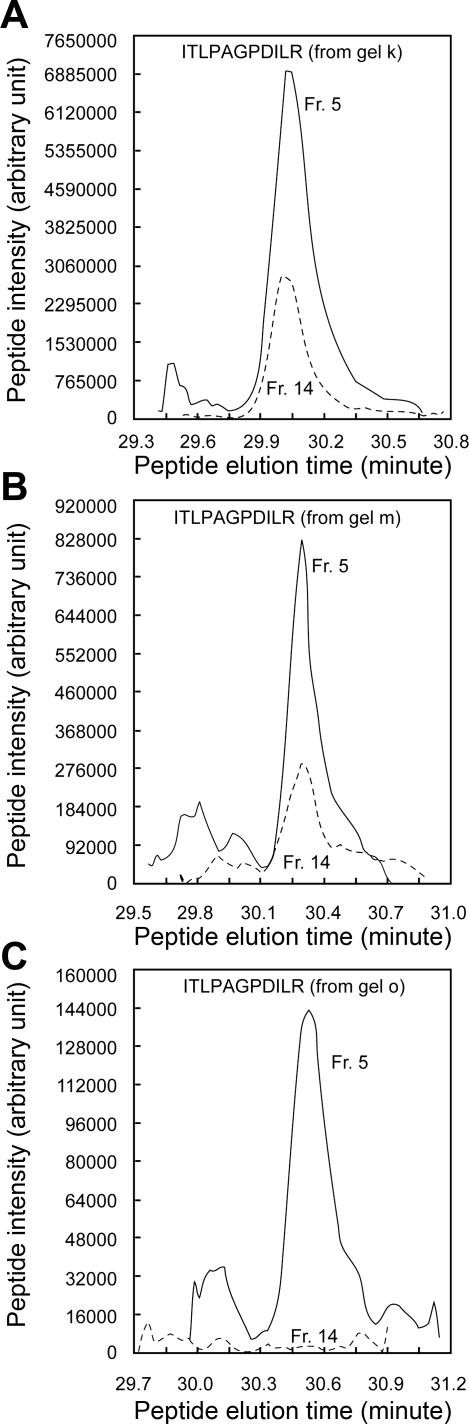

To address whether the DRM fraction contains authentic IMCD membrane raft proteins, the abundance of individual proteins in the DRM and non-DRM fractions was quantified using QUOIL software for label-free quantification (see materials and methods). The hypothesis was that known raft proteins will be enriched in the DRM fraction. To illustrate the quantification process, the known membrane raft protein MAL2 was used as an example. MAL2 was identified by one single peptide in three gel slices (slices k, m, and o; see supplemental Fig. S1), corresponding presumably to the glycosylated MAL2 in slice k and the nonglycosylated MAL2 in slices m and o (29). (See supplemental Fig. S4 for the spectra of the peptide identified.) Figure 2A reconstructs the LC elution profile of the MAL2 peptide identified in gel slice k. The area under the elution profile of the MAL2 peptide identified in fraction 5 (DRM fraction) is greater than that in fraction 14 (non-DRM fraction), indicating a greater abundance of MAL2 in the DRM than in the non-DRM fraction. Figure 2, B and C, shows similar results for the same MAL2 peptide identified in gel slices m and o. The normalized ratios of the areas under these elution profiles in fraction 5 vs. fraction 14 were 12.2 (slice k), 3.7 (slice m), and 32.5 (slice o). A t-test based on the log2 values of these ratios indicated a difference of the mean log2 value from zero (P = 0.04). Because of the positive mean log2 value, the t-test result indicates a higher abundance of MAL2 in the DRM than in the non-DRM fraction.

Fig. 2.

Label-free quantification of MAL2 protein using QUOIL software. A–C: reconstructions of liquid chromatographic (LC) elution profiles of the MAL2 peptide (ITLPAGPDILR with +2 charge) identified in gel slices k, m, and o (see supplemental Fig. S1). Solid line, elution profile reconstructed from fraction 5 (Fr 5); dashed line, elution profile reconstructed from fraction 14 (Fr 14). Areas under the elution profile of the identified MAL2 peptide were used for MAL2 protein (NP_942081.2) quantification by QUOIL software.

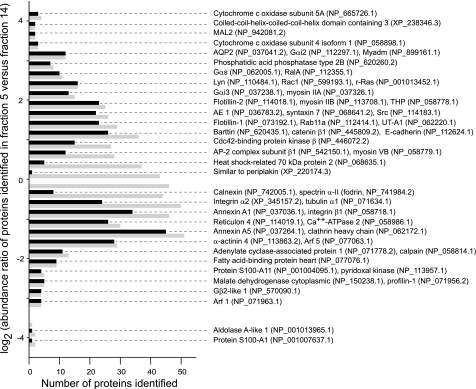

Figure 3 summarizes 639 quantified protein identifications. Each protein was quantified with at least three peptide elution profiles reconstructed from fraction 5 (DRM fraction) and fraction 14 (non-DRM fraction). Because 255 protein quantifications failed the t-test (P > 0.1) described above, their enrichment in one fraction vs. the other could not be concluded. Among the 384 protein quantifications that passed the t-test (P < 0.1), 186 were enriched in the DRM fraction (log2 of ratio >0). The remaining 198 were enriched in the non-DRM fraction (log2 of ratio <0). As shown in Fig. 3, the DRM fraction included several known membrane raft marker proteins, including MAL2, heterotrimeric G protein α-subunits, Lyn tyrosine kinase, flotillins, Tamm-Horsfall protein, and Src tyrosine kinase, indicating enrichment of membrane rafts in the IMCD DRM fraction. AQP2 was identified by LC-MS/MS in the DRM and non-DRM fractions. The vasopressin-regulated urea transporter UT-A1 was identified in the DRM fractions.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of proteins identified in fractions 5 (DRM fraction) and 14 (non-DRM fraction) in IMCD cells. Relative protein abundance in DRM and non-DRM fractions was calculated using QUOIL software on the basis of relative abundance of peptides identified for that protein in fractions 5 and 14. Quantification was based on areas of the LC elution profiles of peptides identified in both fractions (see Fig. 2). Numbers of proteins identified were plotted against mean log2 values of peptide abundance ratios in fractions 5 and 14. Grey bars indicate a total of 639 proteins with ≥3 reconstructed peptide elution profiles for the quantification. Black bars indicate a total of 384 proteins that passed the Student's t-test (P < 0.1) for qualification as IMCD DRM proteins (enriched in fraction 5) or as non-DRM proteins (enriched in fraction 14); 186 proteins were considered IMCD DRM proteins (black bars with mean log2 values >0); 198 proteins were considered non-DRM proteins (black bars with mean log2 values <0). Enrichment in either fraction could not be determined for 255 proteins that did not pass the t-test (P > 0.1). Some sample proteins are shown, along with their RefSeq accession numbers in parentheses.

We next used semiquantitative immunoblotting to examine the results obtained with the quantitative LC-MS/MS method. Twenty-nine of 32 proteins (except E-cadherin, heterotrimeric G protein subunit β2, and Rab5b) showed directionally consistent results between the two methods (Fig. 4A). The ratio of protein abundance in fraction 5 (DRM fraction) to that in fraction 14 (non-DRM fraction) measured by immunoblotting was often higher than that measured by quantitative LC-MS/MS (Fig. 4B). MAL/VIP17 and caveolin-2 were not identified by LC-MS/MS, but both were present in the IMCD DRM fraction, as shown by immunoblotting. Although the exocyst proteins Sec6 and Sec8 were not identified by mass spectrometry, we immunoblotted for these proteins, because the exocyst-associated proteins RalA and RalB were identified by mass spectrometry. Sec6 and Sec8 were present in DRM and non-DRM fractions.

Fig. 4.

A: immunoblot analysis of proteins identified in fraction 5 (IMCD DRM fraction) vs. fraction 14 (non-DRM fraction). Protein (10 μg) of fractions 5 and 14 was separated on a 4–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Proteins were detected with primary antibodies and visualized with fluorophore-coupled species-specific antibodies. Band intensity was quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. Log2 values of protein abundance ratios in fraction 5 vs. fraction 14 by immunoblot (IB) analysis and QUOIL software (means ± SE) analysis are shown. B: results obtained by QUOIL software plotted against results from immunoblot analysis. Solid line, linear regression of 32 data points; dashed line, identical results from QUOIL and immunoblot analysis. RefSeq accession numbers are as follows: NP_112406.1 for β-actin, NP_063970.1 for annexin A2, NP_077069.3 for annexin A4, NP_036910.1 for AQP1, NP_037041.2 for AQP2, NP_742005.1 for calnexin, NP_598412.1 for caveolin-1, NP_112624.1 for E-cadherin, NP_062230.1 for ezrin, NP_073192.1 for flotillin-1, NP_114018.1 for flotillin-2, NP_001013137.1 for Gαi3, NP_062005.1 for Gαs, NP_112249.1 for Gβ1, NP_112299.1 for Gβ2, NP_942081.2 for MAL2, NP_037115.2 for myosin IC, NP_037326.1 for myosin IIA, NP_113708.1 for myosin IIB, NP_058779.1 for myosin VB, NP_059039.1 for myosin light chain 2, NP_036636.1 for Na+-K+-ATPase α1-subunit, NP_062007.1 for NKCC2, NP_068641.2 for syntaxin 7, NP_001073405.1 for Rab5b, NP_112414.1 for Rab11a, NP_112355.1 for RalA, NP_001005765.1 for Rap1a, NP_073180.1 for SNAP23, NP_114183.1 for Src, NP_062220.1 for UT-A1, and NP_036795.1 for VAMP2. Caveolin-2, MAL, Sec6, and Sec8 were not identified by mass spectrometry.

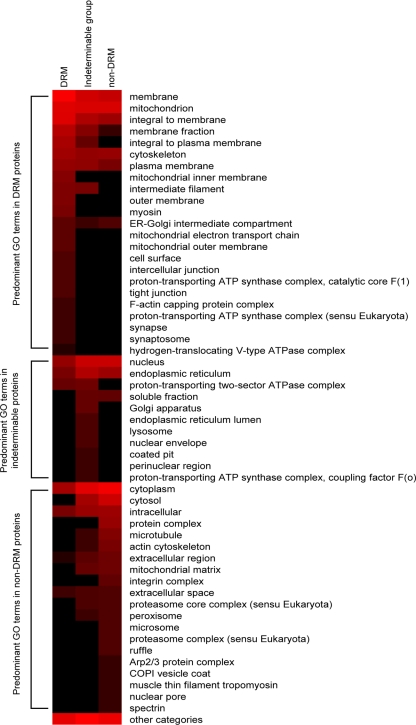

To categorize the data sets of proteins identified with regard to likely cellular distribution, GO terms were extracted for the proteins in the IMCD DRM fractions, the indeterminable group, and the non-DRM fractions. On the basis of the frequency of appearance, the 30 most frequently occurring GO terms from each protein group were clustered into 3 GO term classes: those predominant in the IMCD DRM fraction, those predominant in the indeterminable group, and those predominant in the non-DRM fraction (Fig. 5). For example, as expected, the GO terms including the term “membrane” had a higher frequency of appearance in proteins identified in the DRM fractions than in the other two groups. Membrane-associated GO terms accounted for 46.4% of the total GO terms found in the set of IMCD DRM proteins, consistent with the properties of membrane raft proteins. In addition, variations on the term “mitochondria” were highly represented in the DRM fraction. In contrast, “cytoplasm” and “cytosol” GO terms had the highest frequency of appearance in the non-DRM proteins. This finding was expected, since the density gradient centrifugation was done on total cellular proteins. Only 13.0% of the GO terms found among the non-DRM proteins were associated with membrane. The GO terms that had the highest frequency of appearance in the indeterminable protein group included “nucleus,” “endoplasmic reticulum,” and “Golgi apparatus.” Of the GO terms in the indeterminable protein group, 19.6% were associated with the term “membrane.” Overall, the IMCD DRM had more integral membrane proteins or proteins associated with membranes (P < 0.0001 by χ2 test), whereas the non-DRM list had more proteins that were associated with cytoplasm (P < 0.0001) and cytosol (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

Cellular component gene ontology (GO) term analysis of proteins identified in IMCD DRM fraction, indeterminable protein group, and non-DRM fraction. In the IMCD DRM fraction, 425 cellular component GO terms were associated with 186 unique protein identifications. In the indeterminable group, 433 cellular component GO terms were associated with 255 protein identifications. In the IMCD non-DRM fraction, 316 cellular component GO terms were associated with 198 unique protein identifications. The 30 most frequently occurring GO terms in each fraction were grouped into 3 classes: those predominant in the IMCD DRM fraction, those predominant in the indeterminable group, and those predominant in the non-DRM fraction.

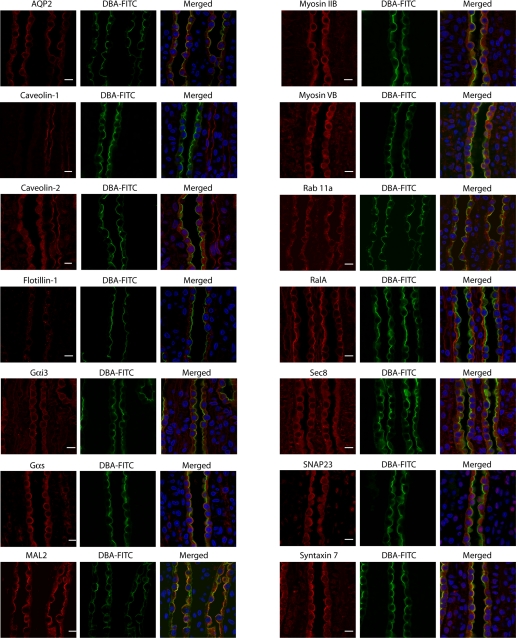

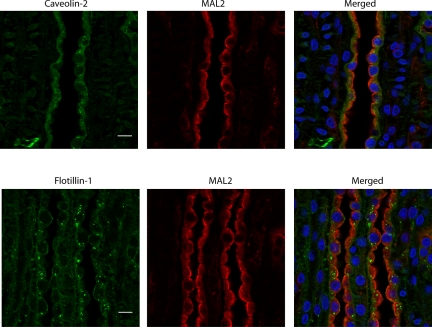

Figure 6 shows confocal immunofluorescence micrographs of 14 DRM proteins in the rat renal inner medulla. Thirteen of 14 proteins, except caveolin-1 (Fig. 6), were detected in IMCD cells identified by the lectin Dolichos biflorus agglutinin conjugated with fluorescein (3, 33). The IMCD marker protein AQP2 was detected in the apical plasma membrane and cytoplasm. Caveolin-1 was found only in non-IMCD structures. Overall, four general staining patterns of DRM-associated proteins indicate heterogeneous distribution of the IMCD DRM proteins: MAL2, RalA, flotillin-1, and caveolin-2 (Fig. 6). MAL2 is present predominantly in the apical and subapical region of the IMCD cells (Fig. 6), whereas RalA is present predominantly at the basolateral plasma membrane (Fig. 6). The other two patterns are best illustrated when the cells are doubly labeled with two of the three classical membrane raft protein markers MAL2, caveolin-2, and flotillin-1 (Fig. 7). Although caveolin-2 has punctate intracellular localization suggestive of the presence of abundant caveosomes, flotillin-1 is predominantly located in large vesicular structures.

Fig. 6.

Confocal immunofluorescence localization of 14 DRM proteins in rat kidney sections. Localization of proteins was detected indirectly using primary antibodies followed by species-specific secondary antibodies (red). Fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) was used to identify IMCDs (green). Labeling with DBA is largely at the apical plasma membrane. Nuclei were visualized with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. RefSeq accession numbers are as follows: NP_037041.2 for AQP2, NP_598412.1 for caveolin-1, NP_073192.1 for flotilllin-1, NP_001013137.1 for Gαi3, NP_062005.1 for Gαs, NP_942081.2 for MAL2, NP_113708.1 for myosin IIB, NP_058779.1 for myosin VB, NP_112414.1 for Rab11a, NP_112355.1 for RalA, NP_073180.1 for SNAP23, and NP_068641.2 for syntaxin 7. Caveolin-1 was identified in the indeterminable protein group. Caveolin-2 and Sec8 were identified by immunoblotting, but not by mass spectrometry.

Fig. 7.

Confocal immunofluorescence localization of 3 classical membrane raft protein markers in rat kidney sections. Localization of proteins was detected indirectly using primary antibodies followed by species-specific secondary antibodies: MAL2 (green) and caveolin-2 and flotillin-1 (red). Nuclei were visualized with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. RefSeq accession numbers are as follows: NP_073192.1 for flotillin-1 and NP_942081.2 for MAL2.

To compare the membrane association mechanisms among the three protein groups (i.e., the DRM proteins, the indeterminable proteins, and the non-DRM proteins), protein information regarding membrane raft-targeting signals and membrane association domains were retrieved from the UniProt Knowledgebase through the PIR website (Table 2). The GPI anchor is one of the best known raft-targeting signals (4). Two GPI-anchored proteins were identified, CD59 and Tamm-Horsfall protein, and both were identified in the IMCD DRM fraction (Table 2). Dual protein acylation provides another raft-targeting mechanism (49). Four proteins were both myristoylated and palmitolyated in the IMCD DRM fraction: Gαi2, Gαi3, and two Src-family tyrosine kinases (Lyn and Src). The singly myristoylated cytochrome b5 reductase was identified in the indeterminable group. Protein palmitoylation often promotes raft association (4). The identification of palmitoylated (but not myristoylated) proteins Gαs, Gαq, SNAP23, and anion-exchange protein 1 (AE1, an integral membrane protein) in the IMCD DRM fraction is consistent with this type of membrane raft-targeting mechanism. Proteins with prenylation are often excluded from membrane rafts (4). However, we found five prenylated small GTP-binding proteins (RalA, RalB, RAP-1A, Rac1, and Rab11) in the IMCD DRM fraction. The SH2 domain can bind phospholipids in addition to phosphorylated tyrosine (16). Two SH2 domain-containing proteins, Lyn and Src tyrosine kinases, were identified in the IMCD DRM fraction. Proteins containing phospholipid-binding PH or C2 domains for membrane association (20) were identified primarily in the non-DRM fraction and the indeterminable protein group. Most annexins associate with membranes via Ca2+-dependent binding to negatively charged phospholipids (16). Annexins were identified chiefly in the non-DRM and the indeterminable protein group.

Table 2.

Analysis of protein identifications for membrane-association mechanisms

| Membrane-Association Mechanism | Proteins in DRM Fraction | Indeterminable Protein Group | Proteins in Non-DRM Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPI anchor | CD59, THP | ||

| Myristoylation | Cytochrome b5 reductase | ||

| Myristoylation + palmitoylation | Gαi2, Gαi3, Lyn, Src, flotillin-2 | ||

| Palmitoylation | Gαs, Gαq, SNAP23 | Caveolin-1 | |

| Palmitoylation + transmembrane domain | AE1 | ||

| Prenylation | Gβ1, RalA, RalB, Rac1, RAP-1A, Rab11a | Rab1a, Rab2a, Rab7, Rab14 | |

| SH2 domain | Lyn, Src | ||

| PH domain | Cdc42-binding protein kinase b | Nonerythroid spectrin-β, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F | β-III spectrin |

| C2 domain | Synaptotagmin-like protein 5, calpain-5 | Membrane-bound C2 domain-containing protein | |

| Annexin repeat | Annexins A2, A4, A6, A7, A11 | Annexins A1, A5 |

Protein information was retrieved from UniProt Knowledgebase accessed through the Protein Information Resource (http://pir.georgetown.edu/). Overall, 75.3% (140 of 186) of proteins identified in the DRM fraction, 86.4% (171 of 198) of proteins identified in the non-DRM fraction, and 76.9% (196 of 255) of proteins in the indeterminable group have curated protein information in the UniProt Knowledgebase. Indeterminable group includes the protein identifications that failed the t-test to be classified for enrichment in the DRM or non-DRM fractions. Type of lipid modification (GPI anchor, myristoylation, palmitoylation, and prenylation) was obtained from the Feature Table (FT) lines in the UniProt entry. These lipid modifications were experimentally proven or predicted by similarity comparison with proteins of the same family that are experimentally proven to carry such modifications. Although not curated in the UniProt database, SNAP23 was known to be palmitoylated (23), Lyn and Src were known to be myristoylated and palmitoylated (4), and Gβγ was known to be prenylated (4). Protein domain or repeat (SH2, PH, C2, and annexin) was based on the Pfam protein domain database entered into the Database cross-Reference (DR) lines in the UniProt entry. Other lipid-binding domains, C1, FYVE, PX, START, and PTB (20), were not found in the identified proteins in the current UniProt database. RefSeq accession numbers are as follows: NP_036783.2 for anion exchange protein 1 (AE-1), NP_037036.1 for annexin A1, NP_001011918.1 for annexin A11, NP_063970.1 for annexin A2, NP_077069.3 for annexin A4, NP_037264.1 for annexin A5, NP_077070.2 for annexin A6, NP_569100.1 for annexin A7, NP_062040.1 for β-III spectrin, NP_604456.1 for calpain-5, NP_598412.1 for caveolin-1, NP_037057.1 for CD59, NP_446072.2 for cdc42-binding protein kinase-β, NP_620232.1 for cytochrome b5 reductase, NP_114018.1 for flotillin-2, NP_112297.1 for Gαi2, NP_037238.1 for Gαi3, NP_112298.1 for Gαq, NP_062005.1 for Gαs, NP_112249.1 for Gβ1, NP_001032364.1 for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F, NP_110484.1 for Lyn, NP_058945.2 for membrane-bound C2 domain-containing protein, NP_001013148.1 for nonerythroid spectrin-β, NP_112414.1 for Rab11a, NP_446041.1 for Rab14, NP_112352.2 for Rab1a, NP_113906.1 for Rab2a, NP_076440.1 for Rab7, NP_599193.1 for Rac1, NP_112355.1 for RalA, NP_446273.1 for RalB, NP_001005765.1 for RAP-1A, NP_073180.1 for SNAP23, NP_114183.1 for Src, NP_848016.1 for synaptotagmin-like protein 5, and NP_058778.1 for Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP).

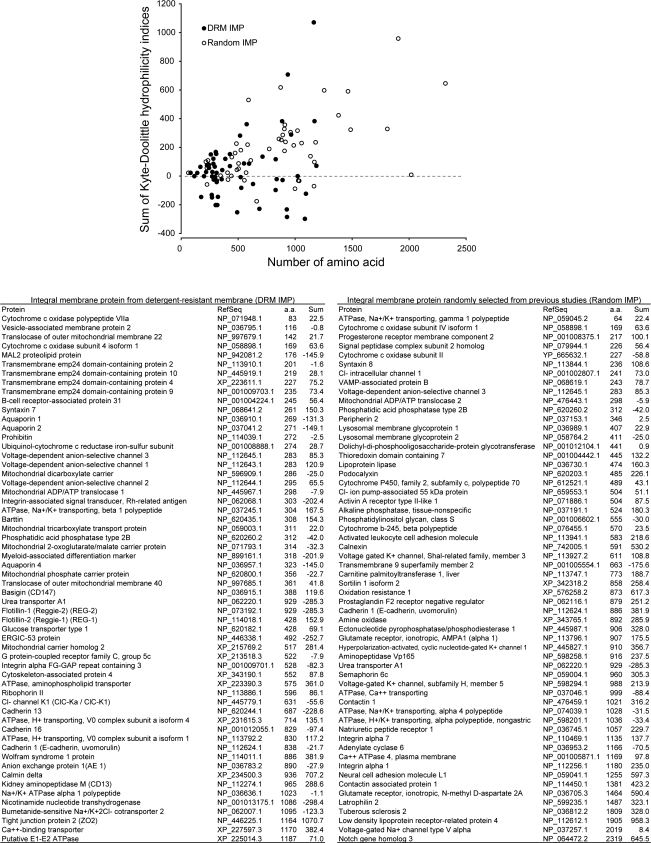

Transmembrane domains of integral membrane proteins are often excluded from membrane rafts (4). However, 58 integral membrane proteins were identified in the IMCD DRM fraction. To explore physical factors associated with integral membrane protein segregation into DRMs, hydrophilicity of the 58 integral membrane proteins identified in the IMCD DRM fractions was compared with that of 58 randomly selected integral membrane proteins identified in previous studies (http://dir.nhlbi.nih.gov/papers/lkem/imp/). As summarized in Fig. 8, the integral membrane proteins in the DRM fraction are significantly smaller (P < 0.00001) and more hydrophobic (with more negative Kyte-Doolittle hydrophilicity values, P < 0.001) than the randomly selected integral membrane proteins.

Fig. 8.

Kyte-Doolittle hydrophilicity analysis of integral membrane proteins (IMPs). IMPs identified in the IMCD DRM fraction (DRM IMP, n = 58) were compared with IMPs randomly selected from previous studies (Random IMP, n = 58). Hydrophilicity indices of each amino acid of a protein was calculated on the basis of a window of 7 amino acids using a World Wide Web interface to the utilities within the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) suite of sequence analysis programs (GCG-Lite, http://molbio.info.nih.gov/molbio/gcglite/). Sum of the hydrophilicity indices of amino acids in a protein (Sum) was assumed to correlate with overall hydrophilicity of the protein and plotted against the number of amino acids (aa) in the protein.

Given that AQP2 is present in the DRM fraction of IMCD cells, one could hypothesize that membrane rafts are involved in regulation of AQP2 trafficking or single-protein water conductance. Consequently, we compared the DRM proteins with proteins previously identified in AQP2-containing vesicles (1) and with proteins identified in apical or basolateral plasma membrane (59) of IMCD cells (Table 3). A number of cargo proteins, including AQP2 and Na+-K+-ATPase, are common to proteomes of the DRM fraction and the AQP2-containing vesicles of the IMCD cells. Also, one of the proteins on the joint list of DRM proteins and AQP2-containing vesicle proteins was Myadm (NP_899161.1), a MARVEL-domain (51) protein closely related to MAL and MAL2. Beyond this, many of the proteins reported in Table 3 were cytoskeletal proteins, scaffold proteins, molecular motors, and related proteins. Heterotrimeric G protein α-subunits, and small GTP-binding proteins, were in the common proteome list. In addition, three soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins, namely, syntaxin 7, syntaxin 13, and VAMP2, were also common to the DRM fraction and the AQP2-containing vesicles. The list also includes adaptor protein (AP-2) complex and four members of the transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein family.

Table 3.

Proteins identified in DRM fraction that were also identified in AQP2-containing vesicles, surface-biotinylated apical plasma membranes, or surface-biotinylated basolateral plasma membranes of IMCD cells

| Protein Name | Gene Symbol | RefSeq | Overlap* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo proteins | |||

| AQP1 | Aqp1 | NP_036910 | AQP2 |

| AQP2 | Aqp2 | NP_037041 | AQP2 |

| ATPase | |||

| Aminophospholipid transporter (APLT) | Atp8a1 | XP_001070245.1 | AQP2 |

| H+ transporting, V0 complex subunit a1 | Atp6v0a1 | NP_113792 | AQP2 |

| H+ transporting, V0 complex subunit d1 | Atp6v0d1 | NP_001011927.1 | AQP2 |

| Na+-K+ transporting, α1 | Atp1a1 | NP_036636.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Na+-K+ transporting, b1 | Atp1b1 | NP_037245.1 | AQP2, BL |

| V1 complex, B2 subunit | Atp6v1b2 | NP_476561.1 | BL |

| Cadherin 16 | Cdh16 | NP_001012055.1 | AQP2 |

| Cadherin 1 (E-cadherin, uvomorulin) | Cdh1 | NP_112624.1 | BL |

| Ceruloplasmin | Cp | NP_036664.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Cl− channel K1 | Clcnk1 | NP_445779 | AQP2 |

| Kidney aminopeptidase M | Anpep | NP_112274.1 | APQ2, AP |

| Cytoskeleton microfilament | |||

| β-Actin cytoplasmic | Actb | NP_112406 | AQP2 |

| α-Actin cardiac | Actc1 | NP_062056.1 | BL |

| Intermediate filament | |||

| Keratin 4 | Krrt4 | NP_001008806 | AQP2 |

| Keratin 7 | Krt7 | NP_001041335.1 | AQP2 |

| Keratin 8 | Krt8 | NP_955402 | AQP2 |

| Keratin 10 | Krt10 | NP_001008804.1 | AQP2 |

| Keratin 18 | Krt18 | NP_446428.1 | AQP2 |

| Keratin 19 | Krt19 | NP_955792 | AQP2 |

| Vimentin | Vim | NP_112402.1 | BL |

| Scaffold proteins | |||

| Erythrocyte protein band 4.1-like 1 isoform S | Epb4.1l1 | NP_742087.1 | AQP2 |

| Plectin 1 | Plec1 | NP_071796.1 | BL |

| Motor and related proteins | |||

| Myosin heavy chain 9, nonmuscle IIA | Myh9 | NP_037326.1 | AQP2, AP, BL |

| Myosin heavy chain 10, nonmuscle IIB | Myh10 | NP_113708.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Myosin Ib | Myo1b | NP_446438.1 | AQP2 |

| Myosin Ic | Myo1c | NP_075580 | AQP2 |

| Myosin Id | Myo1d | NP_037115.2 | BL |

| Myosin light chain, regulatory B | Mrlcb | NP_059039 | AQP2 |

| Myosin light polypeptide 6, smooth muscle and nonmuscle | myl6 | XP_001053789.1 | AQP2 |

| Tropomyosin α-isoform | Tpm1 | AAK54242 | AQP2 |

| Heterotrimeric G proteins | |||

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α inhibiting 2 (Gαi2) | Gnai2 | NP_112297.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α inhibiting 3 (Gαi3) | Gnai3 | NP_037238 | AQP2 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α q (Gαq) | Gnaq | NP_112298 | AQP2 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein, β1 (Gβ1) | Gnb1 | NP_112249 | AQP2 |

| Small GTP-binding proteins | |||

| Rab11a, member of RAS oncogene family | Rab11a | NP_112414 | AQP2 |

| Rap1A, member of RAS oncogene family | Rap1a | NP_002875 | AQP2 |

| Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac 1), Rho family | Rac1 | NP_599193 | AQP2 |

| Related RAS viral (r-Ras) oncogene homolog 2 | Rras2 | NP_001013452.1 | AQP2 |

| V-Ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog B (RalB) | Ralb | NP_446273 | AQP2 |

| SNAREs | |||

| Syntaxin 7 | Stx7 | NP_068641 | AQP2 |

| Syntaxin 13 | Stx13 | AAC18967 | AQP2 |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 | Vamp2 | NP_036795 | AQP2 |

| Trafficking proteins | |||

| Adaptor protein complex (AP-2), α2-subunit | Ap2a2 | NP_112270.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Adaptor-related protein complex 2, β1-subunit | Ap2b1 | NP_542150.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Myeloid-associated differentiation marker | Myadm | NP_899161.1 | AQP2 |

| Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 2 | Tmed2 | NP_113910 | AQP2 |

| Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 4 | Tmed4 | XP_001070563.1 | AQP2 |

| Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 9 | Tmed9 | NP_001009703.1 | AQP2 |

| Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 | Tmed10 | NP_445919 | AQP2 |

| Miscellaneous proteins | |||

| Adenomatous polyposis coli protein | Apc | NP_036631.1 | AP |

| Catenin-β | Ctnnb1 | NP_445809.2 | AQP2, BL |

| Integrin-associated signal transducer, Rh-related antigen | Cd47 | NP_062068.1 | AQP2 |

| Crystallin αB | Cryab | NP_037067.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Heat shock 27-kDa protein 1 | Hspb1 | NP_114176.3 | AQP2, BL |

| Heat shock-related 70-kDa protein 2 | Hspa2 | NP_068635.1 | BL |

| Kinectin 1 | Ktn1 | XP_001073656.1 | AQP2 |

| Methyltransferase-like 7A | Mettl7a | NP_001032432.1 | AQP2 |

| Polyubiquitin | Ubb | NP_620250 | AQP2 |

| Ribophorin 2 | Rpn2 | NP_113886.1 | AQP2, BL |

| Similar to SPFH domain family member 2 | Spfh2 | XP_214372 | AQP2 |

| Mitochondrial proteins | |||

| ADP/ATP translocase 1 | Slc25a4 | NP_445967.1 | AQP2, BL |

| ATP synthase, mitochondrial F0 complex, o subunit | Atp5o | NP_620238.1 | AQP2, BL |

| ATP synthase, mitochondrial F1 complex, α-subunit | Atp5a1 | NP_075581.1 | BL |

| ATP synthase, mitochondrial F1 complex, β subunit | Atp5b | NP_599191.1 | AQP2, BL |

| B-cell receptor-associated protein 37 | Phb2 | NP_001013053.1 | AQP2 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va | Cox5a | NP_665726.1 | BL |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1 | Cox4i1 | NP_058898.1 | AQP2, BL |

| NADH dehydrogenase flavoprotein 2 | Ndufv2 | NP_112326.1 | BL |

| Phosphate carrier protein | Slc25a3 | NP_620800.1 | BL |

| Prohibitin | Phb | NP_114039.1 | BL |

| Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 22 | Tomm22 | NP_997679.1 | AQP2 |

| Ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase complex core protein 2 | Uqcrc2 | NP_001006971.1 | BL |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 1 | Vdac1 | NP_112643 | AQP2 |

| Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 2 | Vdac2 | NP_112644.1 | AQP2, BL |

LC-MS/MS analysis of DRM fractions in vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells.

To identify proteins that may move into and out of the IMCD membrane rafts in response to vasopressin, the DRM fractions from vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells prepared from 20 rats were analyzed with LC-MS/MS using a label-free approach for quantification (see materials and methods). The hypothesis was that a shift of a protein into or out of membrane raft domains could be detected by a change in its abundance in the DRM fractions.

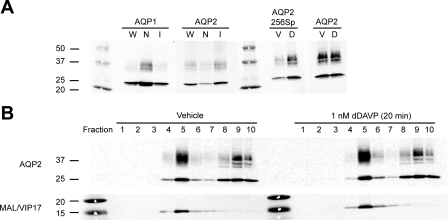

Figure 9A shows the purity and viability of the IMCD cell suspension. The IMCD cell suspension was 6.2-fold enriched with the IMCD marker protein AQP2 and 6.0-fold depleted of the non-IMCD marker protein AQP1 compared with the non-IMCD cell suspension prepared from 20 rats. We estimate that 86% of the total protein in the IMCD-enriched cell suspension was actually from IMCD cells (19). When exposed to 1 nM dDAVP for 20 min, the IMCD cell suspension responded with a 4.0-fold increase in phosphorylation at serine 256 of the AQP2 COOH-terminal tail compared with the vehicle-treated cells, consistent with previous observations (7). In contrast, the amount of total AQP2 was unchanged in the dDAVP-treated cells relative to the vehicle-treated cells. Having established the purity and viability of the IMCD cell suspension, Fig. 9B shows a comparison of the DRM preparations from the vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells from the perspective of several of the DRM proteins identified above. Fraction 5 has the highest abundance of MAL/VIP17 in vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells, defining the location of the DRMs. The immunoblot in Fig. 9B also shows that AQP2 is present in DRM and non-DRM fractions in these preparations and that the distribution of AQP2 is similar between dDAVP- and vehicle-treated IMCD cells. Similar results were observed in two other experiments (see supplemental Fig. S5). The DRM fractions (fractions 4–6) of vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells from the three above-described experiments (60 rats; Fig. 9, also see supplemental Fig. S5) were pooled to obtain sufficient amounts of DRM protein for label-free quantitative mass spectrometric analysis. On average, the three IMCD cell suspensions contained ∼85.0% IMCD cell protein and responded to 1 nM dDAVP with a 3.1-fold increase in AQP2 phosphorylation at serine 256.

Fig. 9.

A: immunoblot assessment of purity and viability of IMCD cell suspension. Each lane was loaded with 10 μg of proteins from IMCD cell suspension (lane I), non-IMCD cell suspension (lane N), and whole inner medulla suspension (lane W) isolated from 20 rats. Antibodies against IMCD marker protein AQP2 and non-IMCD marker protein AQP1 were used to assess purity of cell suspension. Half of IMCD cell suspension was treated with vehicle (lane V) and the other half with [deamino-Cys1,d-Arg8]vasopressin (dDAVP, lane D) for 20 min. Viability of IMCD cell suspension was tested using rabbit antibody against phosphorylated AQP2 at serine 256 (AQP2 256Sp) (41) and chicken antibody against total AQP2 (1). Molecular weight markers are indicated. B: immunoblot assessment of IMCD DRM preparation from vehicle- and 1 nM dDAVP-treated (20 min) IMCD cells. DRM fraction was enriched in fraction 5, where staining for membrane raft marker MAL/VIP17 was the strongest. AQP2 was found in IMCD DRM and non-DRM fractions. Each lane was loaded with a 10-μl protein sample.

With use of filters established by the probability-based target-decoy analysis to set the predicted false-positive identification rate to <2.6%, 94 proteins were identified in the DRM fractions in the vehicle-treated IMCD cells, and 152 proteins were identified in the DRM fractions in the dDAVP-treated IMCD cells (Table 4). [All these protein identifications with their identified peptide sequences and associated statistical scores are listed in supplemental Tables S3 (for vehicle-treated IMCD DRM) and S4 (for dDAVP-treated DRM). Spectra of single-peptide identifications, along with their observed m/z values, are provided in the supplemental Figs. S6 (for vehicle-treated IMCD DRM) and S7 (for dDAVP-treated DRM).] QUOIL software was used to quantify a total of 75 proteins with at least three reconstructed peptide elution profiles in vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD DRM fractions. Only 15 of 75 proteins quantified by LC-MS/MS showed changes in response to 20 min of dDAVP exposure, even with a relatively nonstringent significance criterion (P < 0.1 by t-test; Table 5). Myosin 4, keratin 15, keratin 19, flotillin-2, keratin 12, α-actin, keratin 75, AQP1, Rab7, annexin A2, and keratin 14 showed small increases, whereas β-actin, prohibitin, keratin 10, and annexin A1 showed small decreases, in the IMCD DRM fractions after dDAVP treatment. Among the 60 proteins that did not show significant changes, 16 were previously identified in AQP2-containing intracellular vesicles (Table 3): AQP2, ATP synthase mitochondrial F1 complex α-subunit, ATP synthase mitochondrial F1 complex β-subunit, ATPase V1 complex B2 subunit, ATPase H+-transporting V0 complex subunit d1, ATPase Na+-K+-transporting α1-subunit, B-cell receptor-associated protein 37, crystallin αB, cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1, cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va, heat shock-related 70-kDa protein 2, keratin 4, keratin 8, VAMP2, syntaxin 7, and “similar to SPFH domain family member 2.”

Table 4.

Probability-based target-decoy analysis of protein identifications in DRM fractions of vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells

| No. of Peptides | No. of Proteins | False Positive, % |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle-treated DRM fraction (fraction 5) | ||

| 1 | 62 | 2.533 |

| 2 | 17 | 0.064 |

| 3 | 9 | 0.002 |

| >3 | 6 | ∼0 |

| Total | 94 | |

| dDAVP-treated DRM fraction (fraction 5) | ||

| 1 | 90 | 2.333 |

| 2 | 31 | 0.065 |

| 3 | 12 | 0.002 |

| >3 | 19 | ∼0 |

| Total | 152 | |

Mass spectra were used to search against a concatenated protein database composed of forward and reverse rat RefSeq protein sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Rate of random spectrum matches to reverse sequences was used to estimate rate of false-positive matches to forward sequences. Filter settings to reach false-positive protein identification rates are as follows: Rsp = 1, Xcorr rank: 1, ΔCn > 0.1, Xcorr = 2.56 (+1), 3.06 (+2), and 3.56 (+3) for vehicle-treated DRM fraction and Rsp = 1, Xcorr rank: 1, ΔCn > 0.1, and Xcorr = 1.97 (+1), 2.47 (+2), and 2.97 (+3) for [deamino-Cys1,d-Arg8]vasopressin (dDAVP)-treated DRM fraction.

Table 5.

Proteins of which abundance in DRM fractions changed in response to dDAVP as quantified by LC-MS/MS

| Protein Name; Gene Symbol | Abundance in DRMs | n | P | RefSeq Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myosin 4; Myh4 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 6 | 0.022 | NP_062198.1 |

| Keratin 15; Krt15 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 4 | 0.064 | NP_001004022.1 |

| Keratin 19; Krt19 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 6 | 0.042 | NP_955792.1 |

| Flotillin-2 (Reggie-1, REG-1); Flot2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 5 | 0.089 | NP_114018.1 |

| Keratin 12; Krt12 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 10 | 0.022 | NP_001008761.1 |

| α-Actin cardiac; Actc1 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 24 | 0.089 | NP_062056.1 |

| Keratin 75; Krt75 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 35 | 0.038 | NP_001008828.1 |

| AQP1 (aquaporin-CHIP); AQP1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3 | 0.025 | NP_036910.1 |

| Ras-related protein Rab7; Rab7 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3 | 0.055 | NP_076440.1 |

| Annexin A2; Anxa2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 24 | 0.066 | NP_063970.1 |

| Keratin 14; Krt14 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 26 | 0.045 | NP_001008751.1 |

| β-Actin cytoplasmic; Actb | −0.2 ± 0.1 | 12 | 0.033 | NP_112406.1 |

| Prohibitin; Phb | −0.2 ± 0.1 | 5 | 0.059 | NP_114039.1 |

| Keratin 10; Krt10 | −0.2 ± 0.1 | 58 | 0.023 | NP_001008804.1 |

| Annexin A1; Anxa1 | −0.3 ± 0.1 | 6 | 0.001 | NP_037036.1 |

Values are means ± SE, expressed as log2 relative peptide abundance identified in DRM fractions (fractions 4-6) of vehicle- and dDAVP-treated IMCD cells; n, number of peptide elution profiles. P values are results of t-test to determine whether a given protein identification showed an increase or a decrease in association with the DRM fraction after dDAVP treatment. Several proteins did not show significant changes: AQP2, ATP synthase mitochondrial F1 complex α-subunit, ATP synthase mitochondrial F1 complex β-subunit, ATPase V1 complex B2 subunit, ATPase H+-transporting V0 complex subunit d1, ATPase Na+-K+-transporting α1-subunit, B-cell receptor-associated protein 37, crystallin αB, cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1, cytochrome c oxidase subunit Va, heat shock-related 70-kDa protein 2, keratin 4, keratin 8, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2, syntaxin 7, and similar to SPFH domain family member 2. LC-MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry.

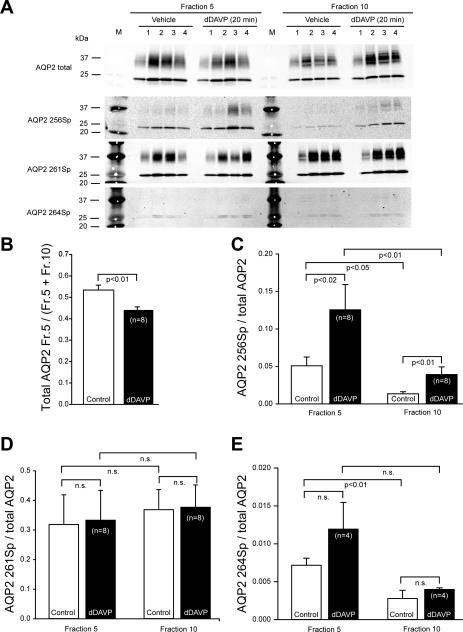

Figure 10A shows representative semiquantitative results of immunoblot analysis of the effects of dDAVP on the DRM association of AQP2. Equal volumes of protein sample from fractions 5 and 10 were chosen to represent the IMCD DRM and non-DRM fractions, respectively. Figure 10, B–E, summarizes results of immunoblot analysis of AQP2 from eight experiments. Neither the total AQP2 in fraction 5 nor the total AQP2 in fraction 10 changed significantly in response to 20 min of exposure to 1 nM dDAVP (not shown). However, there was a very small (∼10%) decrease in the ratio of the amount of AQP2 in fraction 5 to that in fractions 5 + 10 (Fig. 10B). Treatment with dDAVP significantly increased AQP2 phosphorylation at serine 256 in both fractions (Fig. 10C). The ratio of phosphorylated AQP2 at serine 256 to total AQP2 was significantly higher in fraction 5 than in fraction 10 before and after dDAVP treatment (Fig. 10C). Treatment with dDAVP did not change phosphorylation of AQP2 at serine 261 in these fractions (Fig. 10D). There was more phosphorylated AQP2 at serine 264 in fraction 5 than in fraction 10 before dDAVP treatment (Fig. 10E). Phosphorylated AQP2 at serine 264 appeared to increase in response to dDAVP, although the change was not significant.

Fig. 10.

A: representative immunoblots showing effects of dDAVP on association of AQP2 with IMCD DRM fraction. For each experiment (1–4), 20 rats were used for preparation of IMCD cell suspension. Half of suspension was treated with vehicle and the other half with dDAVP for 20 min before DRM preparation. Each lane was loaded with 10 μl of protein from fractions 5 (DRM fraction) and 10 (non-DRM fraction) for immunoblot analysis. AQP2 phosphorylated at serine 256 (AQP2 256Sp), 261 (AQP2 261Sp), and 264 (AQP2 264Sp) was detected with phosphoserine-specific rabbit antibodies (14, 18, 41). Total AQP2 was detected with the chicken antibody (1) that detects nonphosphorylated AQP2 peptide and phosphorylated AQP2 peptides at serines 256 and 261, but not 264 (unpublished data). Lane M, molecular weight markers. B–E: summary of results from 8 experiments, including Fig. 10A and supplemental Fig. S8.

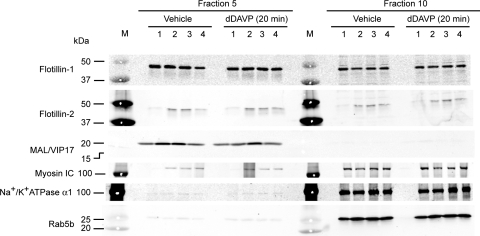

Figure 11 summarizes the effects of dDAVP on the DRM or non-DRM association of several proteins that may play roles in vasopressin-regulated trafficking in the IMCD, namely, flotillin-1, flotillin-2, MAL/VIP17, myosin 1C, Na+-K+-ATPase α1, and Rab5b. Equal volumes of protein sample from fractions 5 and 10 were chosen to represent the IMCD DRM and non-DRM fractions, respectively. None of these proteins showed significant changes in their association with the IMCD DRM or non-DRM fractions in response to 1 nM dDAVP.

Fig. 11.

Immunoblot analysis of effects of dDAVP on association of selected proteins with IMCD DRM fraction. For each experiment (1–4), 20 rats were used for preparation of IMCD cell suspension. Half of suspension was treated with vehicle and the other half with dDAVP for 20 min before DRM preparation. Each lane was loaded with 10 μl of protein from fractions 5 (DRM fraction) and 10 (non-DRM fraction) for immunoblot analysis.

DISCUSSION

We have reported mass spectrometric identification of proteins associated with the DRM fraction from freshly isolated renal IMCD cells. The present study is a continuation of work reported in two previous studies describing IMCD proteins present in AQP2-containing intracellular vesicles (1) and identified by surface biotinylation of apical and basolateral plasma membranes (59). The DRM fraction is a raftlike membrane subfraction derived using the property of membrane insolubility in nonionic detergents at low temperature. These DRMs have characteristic buoyancy, which allows them to accumulate in the interface between the 5% and 35% (wt/vol) sucrose layers during discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation. Although success in expanding the known IMCD proteome does not depend on the assumption that these DRMs are identical to membrane rafts, the profile, nonetheless, suggests that the isolated material has characteristics that have previously been associated with membrane rafts. Bioinformatic analyses of GO terms (Fig. 5) and membrane raft-targeting signals (Table 2) of the identified proteins revealed that the results were consistent with the enrichment of membrane raft proteins in the IMCD DRM fractions. For example, proteins with GPI anchors, as well as proteins that were acylated by myristoylation and/or palmitoylation, were enriched (Table 2).

Label-free quantitative LC-MS/MS analysis using in-house quantification software (QUOIL) allowed statistical classification of identified proteins into three groups: those that were distinctly in the DRM fraction, those that were distinctly in the non-DRM fraction, and an “indeterminable” group that may be in both fractions. Probability-based target-decoy analysis was used to maintain the false-positive protein identification rate at <2.6% in single-peptide identifications and at much lower levels in multiple-peptide identification. Immunoblotting confirmed the QUOIL-based quantification results of 29 proteins that were identified by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 4). In addition to classical raft-associated proteins (GPI anchored and acylated), 58 integral membrane proteins were identified in our IMCD DRM fractions. These DRM-associated integral membrane proteins differed in their physical properties from those found in the IMCD cells, in that they were smaller and more hydrophobic on average (Fig. 8).

Immunofluorescence labeling of IMCDs with use of antibodies to classic raft marker proteins that were found in our proteomic analysis revealed that the raftlike domains in the cells are heterogeneous. In particular, MAL2 showed a predominant labeling of the apical region of the cells, RalA showed a predominant labeling of the basolateral region, caveolin-2 showed a punctate labeling distributed throughout the cells consistent with the intracellular presence of caveosomes, and flotillin-1 showed discrete labeling of large intracellular structures in the cells. Flotillin-1 defines an endosomal fraction that does not colocalize with clathrin and caveolin-1 in the mammalian cell line COS-7 (17). In summary, the confocal localization studies are consistent with marked heterogeneity of the DRM fraction. Thus proteins identified in our proteomic analysis of IMCD DRMs are not necessarily adjacent to one another in a single raftlike structure.

Comparison of the IMCD DRM proteins identified in the present study and proteins identified in other IMCD membrane domains in our previous studies revealed certain classes of proteins in common. In particular, the joint lists (Table 3) reveal consistent identification of proteins associated with the actin cytoskeleton, including certain types of nonmuscle myosins and molecular motors responsible for moving and organizing actin filaments (F-actin) in the cells. In contrast, there did not appear to be enrichment of microtubule-associated proteins or microtubule-based molecular motors. A role for actin in the regulation of AQP2 trafficking by vasopressin has been demonstrated previously (43, 56). The general conclusion from these prior studies is that movement of AQP2-containing vesicles to the apical plasma membrane depends in part on F-actin depolymerization in the subapical cortex of the cells. In addition, we previously found that the ability of vasopressin to increase osmotic water permeability in isolated perfused IMCD segments is markedly impaired by inhibitors of actin polymerization (latrunculin B) or depolymerization (jasplakinolide) (7), as well as inhibitors of myosin light chain kinase (ML-7 and ML-9) (7), inhibitors of calmodulin (W7 and trifluoperazine) (10), and inhibitors of nonmuscle conventional myosins (blebbistatin) (9). Unconventional myosins such as myosin I have been proposed to play a role in organizing raftlike domains through a role in maintaining so-called membrane “skeletons” beneath the plasma membrane (34).

We also found a number of membrane-trafficking proteins in both the protein list for DRMs and the protein list for intracellular AQP2-containing vesicles (Table 3). These proteins include four transmembrane emp24 domain-containing proteins, which are thought to be involved in the early secretory pathway (35), and a small GTP-binding protein (Rab11) involved in endosome recycling (27), a small GTP-binding protein (RalB) associated with exocyst functions (57), and a small GTP-binding protein (Rac1) associated with regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (50). In addition, SNARE proteins, specifically, syntaxin 13 (associated with recycling endosomes) (48) and syntaxin 7 (associated with late endosomes) (32), were among the proteins common to both lists. Thus the proteomic analyses of the DRM fractions and AQP2-containing vesicles revealed several proteins potentially involved in vasopressin signaling and AQP2 trafficking and are consistent with a critical role for endosomal compartments.

An important feature of the IMCD DRM proteome determined in the present study was the predominance of GTP-binding proteins, both small GTP-binding proteins and heterotrimeric G protein α-subunits. The small GTP-binding proteins included those associated with endosomal trafficking (Rab proteins), actin dynamics (Rho-like proteins), exocyst (Ral) proteins, and regulation of the MAP kinase cascade (Ras and Rap proteins). Heterotrimeric G proteins are, of course, involved in signaling, although recent evidence has led to the proposal that these proteins, when present on intracellular vesicles, can play a role in the regulation of membrane trafficking (60). The small and the heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins obviously have potential roles in AQP2 regulation.

AQP2 is known to have a distinct intracellular localization in the kidney collecting duct cells characterized by diffuse labeling with anti-AQP2 antibodies throughout the cytoplasm (53). In our recent proteomics study of AQP2-bearing vesicles immunoisolated from the IMCD cells, we identified small GTP-binding proteins, Rab4/5, Rab11/25, and Rab7, associated with early endosomes, recycling endosomes, and late endosomes, respectively (1). However, we could not identify Rab3, a marker for secretory vesicles, in AQP2-bearing vesicles by immunoblotting and LC-MS/MS methods. These results suggested trafficking of AQP2 to the plasma membrane via endosomes, rather than secretory vesicles (1, 53). Hypothetically, vasopressin may regulate AQP2 trafficking or activation, in part through membrane raft association. Recent work demonstrated a direct binding interaction between AQP2 and the membrane raft protein MAL/VIP17 (25). We tested whether exposure of freshly isolated rat IMCD segments to vasopressin altered the distribution of AQP2 between the DRMs isolated in a manner similar to those used for proteomic analysis and the non-DRM membrane fraction of the IMCD cells. However, vasopressin did not result in a significant change in the AQP2 content of DRMs (Fig. 10). There was a significant 10% decrease in the ratio of AQP2 in fraction 5 to AQP2 in fractions 5 + 10. However, the small magnitude of this change raises concerns about its physiological relevance. Given the heterogeneity of the structures that contribute to biochemically isolated DRMs, it seems possible that a vasopressin response was absent, simply because changes in some raftlike subfractions may have been diluted by the absence of changes in other raftlike subfractions. Interestingly, we also found that the fraction of AQP2 phosphorylated at serine 256 is greater in DRM than in non-DRM fractions, raising the possibility that the kinase responsible for phosphorylation may be associated with membrane rafts or that the phosphatase responsible for dephosphorylation may be associated with nonraft membranes. Alternatively, the serine 256 phosphorylated form of AQP2 may be segregated into raftlike domains, or the nonphosphorylated form may be selectively segregated into nonraft domains.

A possible role for MAL/VIP17 in the raft localization of AQP2 requires further study. MAL/VIP17 is involved in the delivery of some apical membrane proteins (6), as well as clathrin-mediated endocytosis in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (31). Enhancing apical delivery and/or decreasing apical endocytosis will increase apical AQP2 abundance. There is evidence consistent with a vasopressin-induced decrease in clathrin-mediated endocytosis of water channels in collecting ducts (38, 39). The MAL-related proteins MAL2 and Myadm (Table 3) were also identified in the present study. Their role in AQP2 regulation has not been investigated. Marazuela and Alonso (29) proposed that MAL2 is involved in transcytosis. Given that a large fraction of AQP2 is located basolaterally, in addition to apically (11, 24, 36), it seems possible that AQP2 undergoes transcytosis in the process of its targeting to the apical plasma membrane. For example, basolateral AQP2, possibly delivered via an exocyst-dependent mechanism, could undergo endocytosis in the basolateral plasma membrane via caveolae and move in raftlike caveosomes to fuse with the apical plasma membranes (1, 47).

With use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (42) annexin 2 was previously identified as a binding partner of AQP2 in rat kidney inner medulla and was identified in AQP2-bearing vesicles in rat IMCD cells using LC-MS/MS (1). Recently, annexin 2 was shown to translocate from cytosol to membrane fractions in response to forskolin in cultured mouse collecting duct cells (54). This response was associated with a significant increase in the amount of annexin 2 in a membrane raftlike fraction. Our quantitative proteomic results showed a small increase in annexin 2 in IMCD DRMs in response to dDAVP (Table 5), consistent with the suggested role of annexin 2 in AQP2 trafficking.

It was interesting that quantification from label-free LC-MS/MS analysis and quantification by immunoblot analysis was concordant, although the LC-MS/MS approach generally gave lower ratios. The immunoblot analysis was quantified by near-infrared fluorescence (Li-Cor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System), which in our experience is highly linear over at least two orders of magnitude of signal intensity. Thus we suspect that the discrepancy in the quantification values is due to nonlinearity in the nonlabeling LC-MS/MS analysis. Such nonlinearity could conceivably arise from the background correction element of the QUOIL-based analysis. If background correction were consistently too large, the derived ratios between samples would be underestimated. Nevertheless, the high correlation with immunoblot-based quantification supports the validity of the LC-MS/MS quantification.

GRANTS

This research was supported by NHLBI Intramural Research Program Project ZO1-HL-001285.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the professional skills of Zu-Xi Yu and Fillipina Giacometti (Pathology Core Facility, NHLBI), as well as Christian A. Combs and Daniela Malide (Light Microscopy Core Facility, NHLBI), and are grateful for their advice regarding confocal fluorescence microscopy.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barile M, Pisitkun T, Yu MJ, Chou CL, Verbalis MJ, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Large-scale protein identification in intracellular aquaporin-2 vesicles from renal inner medullary collecting duct. Mol Cell Proteomics 4: 1095–1106, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat Biotechnol 24: 1285–1292, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D, Roth J, Orci L. Lectin-gold cytochemistry reveals intercalated cell heterogeneity along rat kidney collecting ducts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 248: C348–C356, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DA Lipid rafts, detergent-resistant membranes, and raft targeting signals. Physiology (Bethesda) 21: 430–439, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown DA, Rose JK. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell 68: 533–544, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheong KH, Zacchetti D, Schneeberger EE, Simons K. VIP17/MAL, a lipid raft-associated protein, is involved in apical transport in MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6241–6248, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou CL, Christensen BM, Frische S, Vorum H, Desai RA, Hoffert JD, de Lanerolle P, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Non-muscle myosin II and myosin light chain kinase are downstream targets for vasopressin signaling in the renal collecting duct. J Biol Chem 279: 49026–49035, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou CL, DiGiovanni SR, Luther A, Lolait SJ, Knepper MA. Oxytocin as an antidiuretic hormone. II. Role of V2 vasopressin receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 269: F78–F85, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou CL, Yu MJ, Kassai EM, Morris RG, Hoffert JD, Wall SM, Knepper MA. Roles of basolateral solute uptake via NKCC1 and of myosin II in vasopressin-induced cell swelling in inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F192–F201, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou CL, Yip KP, Michea L, Kador K, Ferraris JD, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Regulation of aquaporin-2 trafficking by vasopressin in the renal collecting duct. Roles of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores and calmodulin. J Biol Chem 275: 36839–36846, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen BM, Wang W, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S. Axial heterogeneity in basolateral AQP2 localization in rat kidney: effect of vasopressin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F701–F717, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiGiovanni SR, Nielsen S, Christensen EI, Knepper MA. Regulation of collecting duct water channel expression by vasopressin in Brattleboro rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 8984–8988, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenton RA, Knepper MA. Urea and renal function in the 21st century: insights from knockout mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 679–688, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenton RA, Moeller HB, Hoffert JD, Yu MJ, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Acute regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at Ser-264 by vasopressin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3134–3139, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster LJ, De Hoog CL, Mann M. Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5813–5818, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerke V, Creutz CE, Moss SE. Annexins: linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 449–461, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glebov OO, Bright NA, Nichols BJ. Flotillin-1 defines a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 8: 46–54, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffert JD, Nielsen J, Yu MJ, Pisitkun T, Schleicher SM, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Dynamics of aquaporin-2 serine-261 phosphorylation in response to short-term vasopressin treatment in collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F691–F700, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffert JD, van Balkom BW, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Application of difference gel electrophoresis to the identification of inner medullary collecting duct proteins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F170–F179, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurley JH, Misra S. Signaling and subcellular targeting by membrane-binding domains. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 29: 49–79, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue T, Nielsen S, Mandon B, Terris J, Kishore BK, Knepper MA. SNAP-23 in rat kidney: colocalization with aquaporin-2 in collecting duct vesicles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F752–F760, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa SE, Schrier RW. Pathophysiological roles of arginine vasopressin and aquaporin-2 in impaired water excretion. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 58: 1–17, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]