Abstract

A cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) found in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans inhibits the eukaryotic cell cycle, which may contribute to the pathogenic potential of the bacterium. The presence of the cdtABC genes and CDT activity were examined in 40 clinical isolates of A. actinomycetemcomitans from Brazil, Kenya, Japan and Sweden. Thirty-nine of 40 cell lysates caused distension of Chinese hamster ovary cells. At least one of the cdt genes was detected in all strains examined. The three cdt genes were detected, by PCR, in 34 DNA samples. DNA from one strain from Kenya did not yield amplicons of the cdtA and cdtB genes and did not express toxic activity. Restriction analysis was performed on every amplicon obtained. PCR-RFLP patterns revealed that the three cdt genes were conserved. These data provided evidence that the cdt genes are found and expressed in the majority of the A. actinomycetemcomitans isolates. Although a quantitative difference in cytotoxicity was observed, indicating variation in expression of CDT among strains, no clear relationship between CDT activity and periodontal status was found.

Keywords: Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, cdt genes, cytolethal distending toxin, periodontitis

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is associated with the etiology of periodontal diseases, mainly aggressive periodontitis, and with non-oral infections such as endocarditis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, glomerulonephritis and arthritis (9, 33, 36).

The microorganism produces several virulence factors that are involved in the colonization of the oral cavity, the destruction and inhibition of regeneration of the periodontal tissues, and interference with host defense mechanisms (36). The species shows significant variability using either phenotyping or genotyping methods. Genetic methods, such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (AP-PCR), have been successfully used to show that specific genetic variants of A. actinomycetemcomitans are associated with localized juvenile periodontitis (3, 13).

An important consideration in establishing that certain strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans are potentially more virulent than others has been the variable expression of specific virulence determinants. The most thoroughly characterized virulence factor in A. actinomycetemcomitans, the leukotoxin, is genetically comprised of a cluster of four genes that gives this species the ability to kill human neutrophils and macrophages (22, 36). Variation in the transcriptional regulation of the leukotoxin genes divides all A. actinomycetemcomitans into high and low leukotoxin-producing strains. High leukotoxin-producing strains have a deletion in the promoter region of the operon that enhances transcription (5). Variants with the leukotoxin promoter deletion have a high prevalence in young localized juvenile periodontitis-susceptible children who convert from a healthy to a diseased periodontal state (7). However, variants containing the deletion are scarce in patients from Northern European and Scandinavian countries, but are prevalent among localized juvenile periodontitis patients of African origin (17, 18). The contribution of the leukotoxin to localized juvenile periodontitis in populations where the highly leukotoxic clone is absent is uncertain. The presence of low leukotoxin-producing A. actinomycetemcomitans strains in subjects with aggressive forms of periodontal disease as well as in healthy carriers implies that genetic, environmental and acquired factors and, of course, the presence of other periopathogens differentiate the host response to the specific bacterial agent.

Interactions between A. actinomycetemcomitans and eukaryotic cells, relative to cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) expression, are an important consideration in periodontal diseases (24, 31, 34). This toxin arrests the growth of most eukaryotic cells in the G2/M phase (23, 28, 32). CDT is found in several bacterial genera including some Escherichia coli strains (1, 19, 30), Shigella dysenteriae (20, 26), Campylobacter jejuni (21, 27, 37), Haemophillus ducreyi (10) and Helicobacter spp. (8). The prevalence of CDT-expressing clones can vary among populations of the same bacterial species. CDT-positive strains vary from 41% of the samples of Campylobacter spp. in Bangladeshi (21) to 3.1% of the isolates of E. coli from children with diarrhea and only 0.93% of E. coli isolates from healthy children (1). The prevalence of cdt genes in strains varies from very high in certain species, for example H. ducreyi (10), to very low, for example in S. dysenteriae (26) and E. coli (2, 25).

The CdtB protein isolated from C. jejuni and E. coli was shown to be a DNase I-like protein, leading to chromatin fragmentation in susceptible eukaryotic cells (15, 16, 23). The toxin enters the eukaryotic cell by an as yet unidentified mechanism, and binds to the nucleus. The cell cycle is blocked in the G2/M phase, probably as a result of inhibition of the cdc2 cyclin B1 complex (14, 28).

The cdt operon was found in a variable region of the chromosome of A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 by RFLP analysis (13, 24). There are strong indications that the CDT locus in A. actinomycetemcomitans may be of heterologous origin (24). Sonic extracts of members of selected genetic variants (RFLP groups) (13) cause the distension and eventual death of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Deletions in one or more of the cdt genes are prevalent in fresh clinical isolates of A. actinomycetemcomitans (24).

In order to obtain more information on the world-wide distribution of this putative virulence factor in A. actinomycetemcomitans, we determined the presence of the cdtABC genes by PCR, and measured CDT activity against Chinese hamster ovary cells in strains isolated from the subgingival plaque of subjects with various periodontal conditions living in geographically diverse areas.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Forty clinical isolates of A. actinomycetemcomitans were screened for CDT activity with Chinese hamster ovary cells and for cdt genes by PCR. The samples from Sweden (n=7) were isolated in the Department of Microbiology, School of Dentistry, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Samples from Japan (n=5) were isolated from inactive sites of patients with deep pockets (12). Samples from Kenya (n=6) originated from patients without periodontal bone loss or light periodontal disease (11). Strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans from Brazil (n=22) were isolated from patients with various periodontal conditions (Table 1). Samples from periodontally healthy individuals (n=5) were obtained, in a cross-sectional study, from adolescents in the city of São Paulo, Brazil (6). The other Brazilian samples were isolated from patients with aggressive periodontitis (localized juvenile periodontitis) (n=8) and chronic periodontitis (n=9) attending the clinic of the School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, and University Camilo Castello Branco. Strains FDC Y4 (genotype associated with low leukotoxin production) and JP2 and UP6 (genotype associated with high leukotoxin production), originally isolated in the United States from localized juvenile periodontitis patients, were used as controls. The bacteria were kept frozen at −80°C in 10% skim milk (Difco, Sparks, MD).

Table 1.

Race, age and periodontal condition of 18 Brazilian patients from whom 22 A. actinomycetemcomitans samples were isolated

| Strain | Age in years | Race | Periodontal condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| C34-2 | 12 | – | Healthy |

| C51-2 | 12 | – | Healthy |

| C54-2 | 12 | – | Healthy |

| C61 | 12 | – | Healthy |

| C74-2 | 12 | – | Healthy |

| A24 | – | – | Aggressive periodontitis |

| A26 | 19 | Caucasian | Aggressive periodontitis |

| G10-2 | – | – | Chronic periodontitis |

| G56-1 | 18 | Negroid | Aggressive periodontitis |

| G56-4 | 18 | Negroid | Aggressive periodontitis |

| G59-3 | 43 | Caucasian | Chronic periodontitis |

| G81-3 | 46 | Caucasian | Chronic periodontitis |

| G92-1 | 22 | Caucasian | Aggressive periodontitis |

| G101 | 20 | Caucasian | Aggressive periodontitis |

| G101-2 | 20 | Caucasian | Aggressive periodontitis |

| G103-1 | 39 | Caucasian | Chronic periodontitis |

| G103-2 | 39 | Caucasian | Chronic periodontitis |

| G104-1 | 28 | Negroid | Chronic periodontitis |

| G104-2 | 28 | Negroid | Chronic periodontitis |

| G105-2 | 30 | Caucasian | Chronic periodontitis |

| G111-1 | 21 | Caucasian | Aggressive periodontitis |

CDT activity assay

CDT activity was determined as described by Johnson & Lior (19) with the modifications suggested by Scott & Kaper (30). Aliquots from the frozen stock of A. actinomycetemcomitans were inoculated on TSYE agar (tryptic soy agar with 0.6% yeast extract) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C, in 5% CO2. The colonies were scraped from the agar surface, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline solution (pH 7.3) and washed twice in the same solution, and the cells were lysed by sonication for 1 min (Branson Sonifier 450, Branson Ultrasonics Co., Danbury, CT) in an ice bath. The resultant lysates were centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min at 4°C (Eppendorf 5402, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany), to remove unbroken cells and cellular debris. The supernatant fluids were sterilized by filtration through 0.22-μm filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The protein concentrations of the cell lysates were determined using the Micron BCA Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, OH), and the lysates were kept frozen at −80°C until use.

Chinese hamster ovary cells were grown in 250-ml flasks containing 25 ml of F12 Ham’s medium supplemented with 5% bovine fetal calf serum (Cultilab, São Paulo, Brazil), for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Aliquots of 120 μl were removed from the Chinese hamster ovary cell suspensions (2×104cells/ml) and added to each well of 96-well plates (Corning, NY). Aliquots of each bacterial lysate containing 2, 10 or 20μg of protein were diluted to 30μl in F12 Ham’s medium, and added to Chinese hamster ovary cells in each well. The same medium was added to the wells that had not received bacterial extracts as a negative control. Cell lysates of E. coli DH5α(Life Technologies, Gaitherburg, MD) were also tested as a negative control. The medium was removed every 24 h and 150μl of fresh sterile medium containing 1% bovine fetal calf serum was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 4 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. After incubation, the cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 5 min, and stained with 0.2% crystal violet (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). CDT activity was considered to be negative when no morphological changes were observed. CDT activity was considered to be positive when the Chinese hamster ovary cells exhibited the characteristic distension, as in the case of cells treated with lysates from strain FDC Y4, JP2 or UP6 (positive controls). CDT activity was scored as: +, 1–20% distended cells/well;++, 21–70% distended cells and no confluent growth;+++, 70–100% distended cells or lack of cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Amplification of cdt genes

DNA was isolated from A. actinomycetemcomitans strains cultured on TSYE agar in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Isolation of chromosomal DNA was based on the protocol described by Ausubel (4). Briefly, the bacteria were resuspended in 567μl of TRIS-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 7.3) and lysed by the addition of 30μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 3μl proteinase K (20 mg/ml, Gibco, Grand Island, MD) followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h. After cell lysis, 100μl of 53 NaCl and 80μl of 10% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO)/0.73 NaCl were added and the mixture was incubated at 65°C for 10 min. After extraction with phenol (Amresco, Solon, OH)/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (Sigma) (25/24/1 v/v/v), DNA was precipitated with cold ethanol. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol (Amresco) and resuspended in TE buffer (pH 7.3).

To amplify DNA by PCR, primers homologous to each cdt gene were used (Table 2). Primers were constructed based on the FDC Y4 sequence published in GenBank (accession number: AF006830). ‘Ready-To-Go PCR Beads’ (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-five ng of chromosomal DNA and 50 pmol of each primer (1μl) were added to each reaction. Amplification was performed for 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min, in a thermocycler (Perkin Elmer Amp Gene, Norwalk, CT). Negative controls containing sterile water instead of DNA, and positive controls containing FDC Y4 chromosomal DNA as the template were included with every experiment. Experiments in which no amplicon was obtained, for at least one of the cdt genes, were repeated using primers cdt (A)-pcr1 and cdt (C)-pcr2 as described above. The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels (Sigma), in Tris-acetate-Edta (TAE) buffer at 70 V for 2 h. The amplicons were visualized with an ultraviolet transilluminator (Gel Doc 1000, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Table 2.

Primers used in amplification of each cdt gene from A. actinomycetemcomitans, designed based on the analysis of the sequence of strain FDC Y4 (GenBank accession number AF006830)

| Primer | Sequence | Analysis | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cdt (A)-PCR1 | 5′?GGTTTAGTGGCTTGT 3′ | cdtA | 583 |

| cdt (A)-PCR2 | 5′?CACGTAATGGTTCTGTT 3′ | ||

| cdt (B)-PCR1 | 5′?GGTTTTCTGTACGATGT 3′ | cdtB | 790 |

| cdt (B)-PCR2 | 5′?GGATGTAATTTGTGAGCGT 3′ | ||

| cdt (C)-PCR1 | 5′?GACTTTGACGAGTCATGCA 3′ | cdtC | 512 |

| cdt (C)-PCR2 | 5′?CCTGATTTCTCCCCA 3′ | ||

| cdt (A)-PCR1 | 5′?GGTTTAGTGGCTTGT 3′ | cdtABC | 2065 |

| cdt (C)-PCR2 | 5′?CCTGATTTCTCCCCA 3′ |

RFLP analysis

Amplicons representing the cdtA, B or C gene, or the entire operon (cdtABC), were digested with a restriction endonuclease in a volume of 30μl, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Gibco). Restriction endonucleases (shown in Table 3) were selected on the basis of unique cleavage sites in each of the genes. The frequencies of restriction endonuclease cleavage sites were determined using the LASERGENE MAP DRAW 4.05 Program (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) and the FDC Y4 DNA sequence (GenBank accession number AF006830). The digested amplicons were resolved by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels, in TAE buffer at 70 V, for 2 h. The DNA fragments were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed.

Table 3.

Number and position of restriction sites in amplicons of cdt genes, based on the analysis of the sequence of strain FDC Y4 (GenBank accession number AF006830)

| PCR product | Restriction enzyme | Sites | Fragment (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cdtA | FokI | 1 | 139 e 444 |

| HaeII | 1 | 242 e 341 | |

| HindIII | 1 | 381 e 202 | |

| cdtB | EcoRII | 1 | 248 e 542 |

| HindIII | 1 | 363 e 427 | |

| NspI | 1 | 455 e 335 | |

| cdtC | DraI | 1 | 223 e 289 |

| EcoRII | 1 | 256 e 256 | |

| BclI | 1 | 289 e 223 |

Results

CDT activity

CDT activity was evaluated by microscopic observation of Chinese hamster ovary cells 4 days after exposure to A. actinomycetemcomitans cell lysates. Lysate from E. coli DH5αdid not alter the morphology of the Chinese hamster ovary cells. Chinese hamster ovary cells treated with lysates from A. actinomycetemcomitans strain FDC Y4, UP6 or JP2 (positive controls) exhibited the characteristic alterations in shape caused by CDT.

The effects of increasing concentrations of total cell lysate from the various A. actinomycetemcomitans isolates on the Chinese hamster ovary cells are shown in Table 4. These results were reproducible in triplicate experiments. Toxin activity was scored on the basis of the percentage of Chinese hamster ovary cells in the culture that exhibited a morphological change relative to controls (Fig. 1). Lysate from 39 of 40 clinical isolates caused an aberration in Chinese hamster ovary cell morphology (97.5%). Only strain OMGS414, from Kenya, did not affect Chinese hamster ovary cell shape and number, even when as much as 20μg protein/well was added. However, as shown in Table 4, the amount of distension differed among lysates from the various isolates. Cell lysates from only 19 strains exhibited CDT activity at similar or higher levels than that observed for strain FDC Y4. Strains JP2 and UP6 caused more pronounced alterations in cell shape and number than strain FDC Y4. Lysates from only two isolates of A. actinomycetemcomitans, both from patients with aggressive periodontitis (localized juvenile periodontitis), produced an effect on Chinese hamster ovary cells of the same magnitude as that caused by strains JP2 and UP6.

Table 4.

Toxic activity on Chinese hamster ovary cells of cell lysates from 40 clinical isolates and three control strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and detection of cdtABC genes by PCR

| Strain | CDT activity based on total protein (μg/well)1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 10 | 20 | Amplicons2 | |

| USA | ||||

| FDC Y4 | + | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| JP2 | + | ++ | +++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| UP6 | + | ++ | +++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| Brazil | ||||

| A24 | + | + | ++ | cdtB, cdtC, cdtABC |

| A26 | + | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| C34-2 | + | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| C51-2 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| C54-2 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtC, cdtABC |

| C61 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB |

| C74-2 | + | + | + | cdtB, cdtC |

| G10-2 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G56-1 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtC, cdtABC |

| G56-4 | + | + | + | cdtB, cdtC, cdtABC |

| G59-3 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G81-3 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G92-1 | ++ | ++ | +++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G101 | ++ | ++ | +++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G101-2 | + | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G103-1 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G103-2 | + | + | ++ | cdtB, cdtABC |

| G104-1 | − | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G104-2 | ++ | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G105-2 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G111-1 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| G121-3 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| Sweden | ||||

| OMGS161 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 181 | + | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtC, cdtABC |

| OMGS 183 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 194 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 250 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 252 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 2460 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| Kenya | ||||

| OMGS 414 | − | − | − | cdtC |

| OMGS 420 | + | + | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 443 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 449 | + | + | + | cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 722 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 723 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| Japan | ||||

| OMGS 1519 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB |

| OMGS 1520 | + | + | + | cdtB |

| OMGS 1522 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 1523 | + | ++ | ++ | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

| OMGS 1526 | + | + | + | cdtA, cdtB, cdtC |

−, absence of activity;+, 1–20% distended cells;++, 21–70% distended cells with loss of the confluent growth;+++, 70–100% distended cells and/or absent cells.

cdtA, amplicon using primers cdt(A)-PCR1 and cdt(A)-PCR2;cdtB, amplicon using primers cdt(B)-PCR1 and cdt(B)-PCR2;cdtC, amplicon using primers cdt(C)-PCR1 and cdt(C)-PCR2;cdtABC, amplicons in samples that, even if some of the cdt genes were not detected separately, gave a positive result during the amplification with the cdt (A)-PCR1 and cdt (C)-PCR2 primers.

Fig. 1.

Appearance of Chinese hamster ovary cells after 4 days of exposure to cell lysates of A. actinomycetemcomitans. (A) No bacterial lysate;(B) bacterial lysate from strain OMGS 2460 (2.0 μg of protein/well, 1–20% of distention, +);(C) bacterial lysate from strain G92-1 (10.0 μg of protein/well, 21–70% of distention, ++);(D) bacterial lysate from strain G92-1 (20.0 μg of protein/well, 70–100% of distention, +++).

Identification and analysis of cdt genes

PCR reactions using primers homologous to the cdtA, B and C genes were performed with DNA from the 40 isolates of A. actinomycetemcomitans. The results are shown in Table 4. Amplification of the cdt genes in strains Y4 and JP2 was obtained in every PCR experiment. DNA from all strains produced a single amplicon, of the expected size, for at least one of the three cdt genes. Figure 2 shows the amplicons for the cdtA, B and C genes for the Y4 strain.

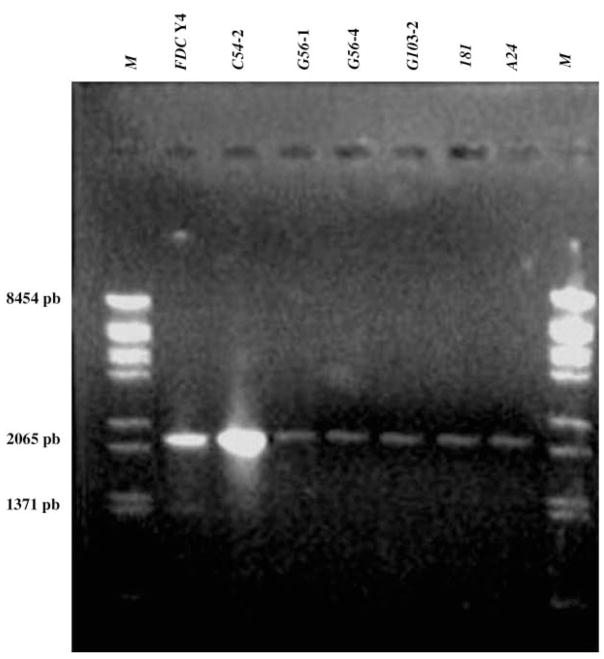

Fig. 2.

RFLP patterns of cdt genes from strain FDC Y4. M, molecular weight marker (50 bp DNA ladder).

Negative results were obtained with DNA from 12 of the isolates. These DNA samples were amplified again using primers cdt (A)-PCR 1 and cdt (C)-PCR 2 in an attempt to produce an amplicon containing all three cdt gene sequences. DNA from six (A24, C54-2, G56-1, G56-4, G103-2 and OMGS181) of the 12 previously negative strains yielded amplicons of the expected size of 2065 bp (Fig. 3). The three cdt genes were amplified from 34 of 40 clinical isolates examined. These same strains also expressed CDT activity. DNA from the remaining six strains, two isolated from periodontally healthy patients (C61 and C74-2) from Brazil, two from Kenyan patients (OMGS 414, adult gingivitis, and OMGS 449, adult periodontitis) and two from Japanese patients (OMGS 1519 and OMGS 1520: deep pocket, inactive sites), did not produce an amplicon for at least one of the cdt genes, nor exhibited the complete operon (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

PCR of total DNA from representative strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. Primers cdt (A)-PCR 1 and cdt (C)-PCR 2 were used. M, molecular weight marker (low range molecular I DNA).

The PCR products obtained from each reaction were digested with restriction endonucleases to produce RFLP patterns (Table 3). Amplicons from all tested strains yielded DNA fragments of the expected sizes as compared to FDC Y4 (see Fig. 2). Amplicons representing the intact operon (genes cdtABC), from those strains that did not yield PCR products for the individual cdt genes, were also subjected to RFLP analysis (Fig. 4). No differences in restriction sites were detected.

Fig. 4.

Restriction endonuclease map of the cdt gene region of strain FDC Y4. Amplicons cdtA-PCR (583 bp), cdtB-PCR (790 bp), cdtC-PCR (512 bp) and cdtABC-PCR (2065 bp) are designated by the heavy lines.

Discussion

Although A. actinomycetemcomitans is linked to the etiology of localized juvenile periodontitis, the bacterium is also found in subjects who are healthy or have other forms of periodontal disease. Differences in the virulence potential of strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans may explain why some subjects are carriers and why there is an increased prevalence of A. actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis in certain populations. Cytolethal distending toxin genes have been detected in A. actinomycetemcomitans and in other organisms, their prevalence varying according to the bacterial species (8, 10, 19, 21, 26). In this study we examined isolates from geographically diverse locations to evaluate the distribution of cytolethal distending toxin activity and the presence of cdt genes among strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Total cell lysates from 39 of 40 clinical isolates induced morphological changes in Chinese hamster ovary cells associated with CDT. However, distending activity similar to or higher than that expressed by FDC Y4 was found in only 21 of 42 strains tested, including strains UP6 and JP2. This variation in CDT activity in A. actinomycetemcomitans has also been observed among isolates from the United States (24). In that study, lysates from four genetic variants of A. actinomycetemcomitans had low levels of toxin activity. Lysates from 10 RFLP variants lacked CDT activity.

Twelve of the isolates examined in this study lacked at least one of the cdt genes as determined by PCR analysis. This was not surprising, as the cdt gene locus appears to reside in a highly unstable region on the FDCY4 chromosome and naturally occurring mutants have been reported (24). Six of these 12 strains exhibited amplicons when the whole cdtABC gene operon was amplified using primers homologous to the 5′?end of cdtA and the 3′?end of cdtC. These results indicated the presence of the genes, although there was probably an absence of homology with the primers used. These data were reinforced by the fact that strains A24, G103-2 and OMGS181 did not show amplicons for the cdtA or the cdtB genes alone but showed amplicons for the entire operon (cdtABC), and had a toxic effect on Chinese hamster ovary cells similar to that induced by strain FDC Y4 cell lysate.

CDT activity was observed with cell lysates from five strains in which cdtA, cdtC or cdtABC was not detected by PCR. However, it should be noted that the toxic effects caused by cell lysates from these strains [two isolates from healthy subjects in Brazil (C61 and C74-2), one from a patient in Kenya (OMGS 449) and two from patients in Japan (OMGS1519 and OMGS1520)] were lower than that observed with lysate from strain FDC Y4. The change in cell morphology occurred in less than 20% of the Chinese hamster ovary cells, even when up to 20μg of protein was added per well (Table 4).

The absence of amplicons from these strains may be attributable to a deletion of the gene or lack of homology with the primer. However, it is also possible that there is a partial gene deletion without a corresponding loss of toxin activity. It has been reported that the product of cdtC is essential for the cytotoxic effect of A. actinomycetemcomitans (31). Mayer et al. (24) observed that anti-CdtC monoclonal antibodies inhibited CDT activity. However, this same study showed that a gene insertion 24 nucleotides upstream from the 3′end of the cdtC gene resulted in no loss of activity. These data indicate that the last eight amino acids do not play a role in the function of cdtC. In the present study, primer cdt(C)-PCR 2 is located on the 3′side of the restriction site PinAI, where the interposon was inserted in cdtC (24). These data suggest that naturally occurring mutants carrying a partial deletion in cdtC may be able to maintain toxic activity.

Recent data have shown that cdtB is the main component of a putative holotoxin (15, 16, 23). In the present study, strain OMGS1520 from Japan exhibited an amplicon containing only the cdtB sequence. Yet, this strain expressed low CDT activity. The only strain in which cdtB was not amplified, OMGS414 from Kenya, did not exhibit a cytolethal effect, supporting the concept that cdtB is an absolute requirement for the expression of toxin activity.

RFLP analysis of the amplicons (PCR-RFLP) revealed that the restriction endonuclease sites were conserved in genes cdtA, B and C in most of the clinical isolates and in strain JP2. These data are in agreement with those of Shenker et al. (32) comparing the sequence of cdt genes of a minimally leukotoxic strain, A. actinomycetemcomitans 652, with the sequences published in GenBank for the minimally leukotoxic strains FDC Y4 and ATCC 29522, and for the highly leukotoxic strain HK1651 isolated in Europe from a localized juvenile periodontitis patient of African origin.

The present data indicate that cdt genes and CDT activity are commonly found in strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans from diverse geographical locations. The cdt genes and CDT activity were found in strains from patients with every periodontal condition, as the Brazilian isolates represented strains from patients with chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis and a healthy periodontium. Although all strains induced morphological changes in Chinese hamster ovary cells, the activity or amount of toxin produced differed among strains. Strain FDC Y4 promoted distension of more than 20% of the Chinese hamster ovary cells (designated ++) with the addition of 20μg of cell lysate protein per well (Table 4). However, 20 of 40 clinical isolates were unable to initiate CDT effects in more than 20% of the cells, even when 20μg of protein was added to cultures. Cell lysates from four of the five isolates from healthy subjects from Brazil caused very little alteration in Chinese hamster ovary cells. In contrast, 13 strains, including strains JP2 and UP6, exhibited a highly toxic effect even when doses of protein from cell lysates were ≤10μg. The only two strains that showed the toxic effect on >70% of the Chinese hamster ovary cells, an effect similar to that observed for strains JP2 and UP6, were isolates from Brazilian patients with localized juvenile periodontitis. However, no clear relationship between CDT activity and periodontal status was found.

Cytolethal distending toxin activity and cdt genes were frequently found in strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans from diverse geographical locations and were not specific for certain clones. However, quantitative differences in CDT production were observed among strains, which could be reflected in the virulence of the bacterium.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by FAPESP Grant 98/15596-4 to MPAM and USPHS Grant RO1-DE12593 to JMD.

References

- 1.Albert MJ, Faruque SM, Faruque ASG, et al. Controlled study of cytolethal distending toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in Bangladeshi children. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:717–719. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.717-719.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansaruzzaman M, Albert MJ, Nahar S, et al. Clonal groups of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated in case-control studies of diarrhea in Bangladesh. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:177–185. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-2-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asikainen S, Chen C, Saarela M, Saxen L, Slots J. Clonal specificity of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in destructive periodontal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(Suppl 2):S227–S229. doi: 10.1086/516211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, et al. Short protocols in molecular biology. 4. New York, USA: Wiley–Interscience; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brogan JM, Lally ET, Poulsen K, Kilian M, Demuth DR. Regulation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin expression: analysis of the promoter regions of leukotoxic and minimally leukotoxic strains. Infect Immun. 1994;62:501–508. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.501-508.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunetti MC, Mayer MPA, Novelli MD, Zelante F, Ando T. Prevalence of bone loss and detection of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in Brazilian schoolchildren. J Dental Res. 1996;75 abstract 659:100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bueno LC, Mayer MPA, DiRienzo JM. Relationship between conversion of localized juvenile periodontitis-susceptible to disease and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin children from health promoter structure. J Periodontol. 1998;69:998–1007. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chien C-C, Taylor NS, Ge Z, Schauer DB, Young VB, Fox JG. Identification of cdt B homologues and cytolethal distending toxin activity in enterohepatic Helicobacter spp. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:525–534. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-6-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collazos J, Dias F, Mayo J, Martinez E. Infectious endocarditis, vasculitis, and glomerulonephritis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1342–1343. doi: 10.1086/517800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cope LD, Lumbley S, Latimer JL, et al. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4056–4061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlén G, Manji F, Baelum V, Fejerskov O. Black-pigmented Bacteroides species and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in subgingival plaque of adult Kenyans. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:305–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlén G, Lindhe J, Sato K, Hanamura H, Okamoto H. The effect of supragingival plaque control on the subgingival microbiota in subjects with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:802–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb02174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiRienzo JM, McKay TL. Identification and characterization of genetic cluster group of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans isolated from the human oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:75–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.75-81.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escalas N, Davezac N, De Rycke J, Baldin V, Mazars R, Ducommun B. Study of cytolethal distending toxin-induced cell cycle arrest in HeLa cells: involvement of the CDC25 phosphatase. Exp Cell Res. 2000;257:206–212. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elwell CA, Dreyfus LA. DNase I homologous residues in CdtB are critical for cytolethal distending toxin-mediated cell cycle arrest. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:952–963. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elwell C, Chao K, Patel K, Dreyfus L. Escherichia coli CdtB mediates cytolethal distending toxin cell cycle arrest. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3418–3422. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3418-3422.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haubek D, Poulsen K, Asikainen S, Kilian M. Evidence for absence in Northern Europe of especially virulent clonal types of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:395–401. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.395-401.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haubek D, Poulsen K, Westergaard J, Dahlén G, Kilian M. Highly toxin clone of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in geographically widespread cases of juvenile periodontitis in adolescents of African origin. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1576–1578. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1576-1578.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson WM, Lior H. Response of Chinese hamster ovary cells to a cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) of Escherichia coli and possible misinterpretation as heat-labile (LT) enterotoxin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;43:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson WM, Lior H. Production of Shiga toxin and a cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) by serogroups of Shigella spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson WM, Lior H. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Campylobacter spp. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lally ET, Hill RB, Kieba IR, Korostoff J. The interaction between RTX toxins and target cells. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:356–361. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lara-Tejero M, Galán JE. A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonucleases I-like protein. Science. 2000;290:354–357. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer MPA, Bueno LC, Hansen EJ, DiRienzo JM. Identification of a cytolethal distending toxin gene locus and features of a virulence-associated region in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1227–1237. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1227-1237.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Steinruck H, Kaper JB. Characterization of Escherichia coli strains from cases of childhood diarrhea in provincial southwestern Nigeria. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:7–12. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.7-12.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okuda J, Kurazono H, Takeda Y. Distribution of the cytolethal distending toxin A gene (cdtA) among species of Shigella and Vibrio, and cloning and sequencing of the cdt gene from Shigella dysenteriae. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(95)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickett CL, Pesci EC, Cottle DL, Russee G, Erdem AN, Zeytin H. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin production in Campylobacter jejuni and relatedness of Campylobacter sp cdt B genes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2070–2078. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2070-2078.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickett CL, Whitehouse CA. The cytolethal distending toxin family. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:292–297. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purdy D, Buswell CM, Hodgson AE, McAlpine K, Henderson I, Leach SA. Characterization of cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) mutants of Campylobacter jejuni. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:473–479. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-5-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott DA, Kaper JB. Cloning and sequence of the genes encoding Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:244–251. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.244-251.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenker BJ, McKay T, Datar S, Miller M, Chowhan R, Demuth D. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans immunosuppressive protein is a member of the family of cytolethal distending toxins capable of causing a G2 arrest in human T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:4773–4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shenker BJ, Hoffmaster RH, McKay TL, Demuth DR. Expression of the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) operon in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: evidence that the CDTB protein is responsible for G2 arrest of the cell cycle in human T cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:2612–2618. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slots J, Ting M. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in human periodontal disease: occurrence and treatment. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:82–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugai M, Kawamoto T, Pérès SY, et al. The cell cycle-specific growth-inhibitory factor produced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a cytolethal distending toxin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5008–5019. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.5008-5019.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinoco EMB, Beldi MI, Loureiro CA, et al. Localized juvenile periodontitis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the Brazilian population. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson M, Henderson B. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans relevant to the pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal diseases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;17:365–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitehouse CA, Balbo PB, Pesci EC, Cottle DL, Mirabito PM, Pickett CL. Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin causes a G2-phase cell cycle block. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1934–1940. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1934-1940.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]