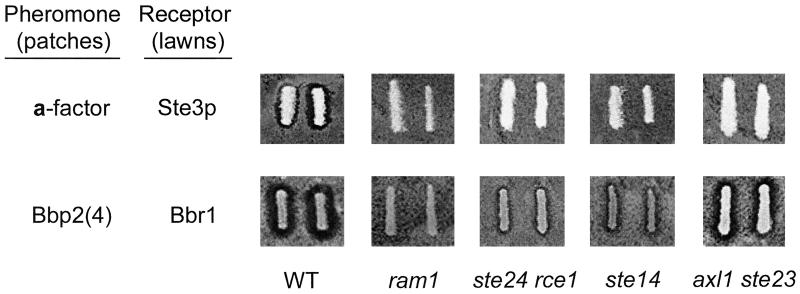

Figure 7.

Active, secreted Bbp2(4) requires only some of the a-factor processing and modification machinery. Halo assays, in duplicate, were done as in Figure 4A. Top row: Secreted a-factor was monitored using halo assays on MATα sst2 STE3 (Tn44–1B) lawns. MATa cell patches tested for a-factor production were the wild-type parental strain (“WT”, SM1058) and isogenic mutants defective in farnesylation (ram1, LHK1), C-terminal processing (ste24 rce1, SM3614), carboxyl methylation (ste14, SM1188), and N-terminal processing (axl1 ste23, SM2744), all containing pPGK. Bottom row: A MATa mfa1 mfa2 mutant strain (SM2331) containing pPGK-bbp2(4) (“WT”) served as the control for Bbp2(4) production. The ram1, ste24 rce1, ste14, and axl1 ste23 mutant strains described above, but containing pPGK-bbp2(4), were tested for Bbp2(4) production. Halo assays were done on MATα sst2 ste3 (SDK47) lawns containing pPGK-bbr1. Quantifications of Bbp2(4) activity in the ste24 rce1 and ste14 mutants were done by FUS1-lacZ reporter gene assays (see text for details). The same mutant strains containing pPGK, tested on MATα sst2 ste3 (SDK47) lawns containing pPGK-bbr1, showed no halo effect (our unpublished data).