Abstract

An interesting goal of nanotechnology is to assemble biomolecules to display multivalent interactions, which are characterized by simultaneous binding of multiple ligands on one biological entity to multiple receptors on another with high avidity1. Various approaches have been developed to engineer multivalency by linking multiple ligands together2-4. However, the effects of well-controlled inter-ligand distances on multivalency are less understood. Recent progress in self-assembling DNA tile-based nanostructures with spatial and sequence addressability5-12 has made deterministic positioning of different molecular species possible8,11-13. Here we show that distance-dependent multivalent binding effects can be systematically investigated by incorporating multiple affinity ligands into DNA nanostructures with precise nanometer spatial control. Using atomic force microscopy (AFM), we demonstrate direct visualization of high avidity bivalent ligands being used as pincers to capture and display protein molecules on a nanoarray. Our results set forth a path for constructing spatial combinatorics at the nanometer scale.

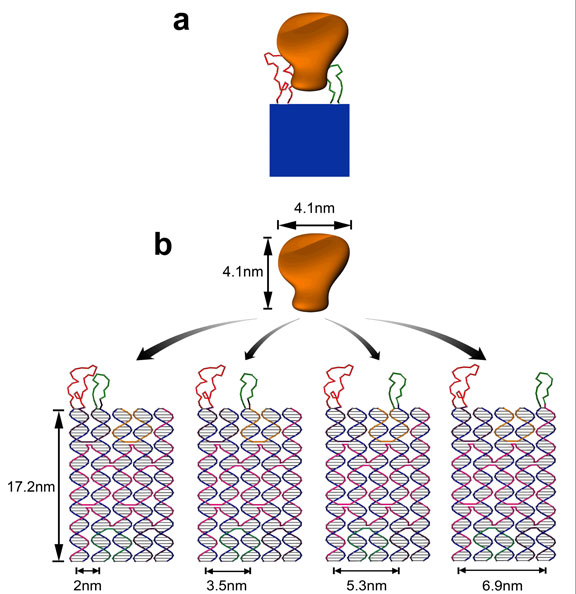

The model system (Fig. 1) we chose to demonstrate the distancedependent multivalent ligand-protein binding consists of two different aptamers positioned into a multi-helix DNA tile to bind a single protein target, such that the distance between them can be precisely controlled by varying the spatial arrangement of the aptamers on the DNA tile. Aptamers are oligonucleotidebased recognition regions that are selected to bind small molecules or proteins14. The two aptamers used here both are thrombin (a coagulation protein involved as a key promotor in blood clotting) binding aptamers which were previously selected and well characterized15,16. Each has a unique sequence and binds to a nearly opposite site on the thrombin molecule15,17, 18. Aptamer A (apt-A: 29 mer, 5′-AGT CCG TGG TAG GGC AGG TTG GGG TGA CT-3′) binds to the heparin binding exosite,15 and aptamer B (apt-B: 15 mer, 5′-GGT TGG TGT GGT TGG-3′) binds primarily to the fibrinogen-recognition exosite.16 It is proposed that, when these two aptamers are linked together by a rigid spacer, by varying the length of the space, an optimal inter-aptamer distance will be achieved, so that the two aptamers will act as a bivalent single molecular species that displays a stronger binding affinity to the protein than any one of the individual aptamers alone does.

Figure 1. Schematics of the self-assembled divalent aptamers on DNA tile for protein binding.

a, A cartoon showing a rigid DNA tile (blue) that can spatially separate two ligands (red and green) at a controlled distance with each ligand attaches to a different part of the target molecule (orange) for bivalent binding. b, 5-helix-bundle (5HB) DNA structure with apt-A (red) and apt-B (green) protruding out of the tile helices and being separated at a distance of 2, 3.5, 5.3, and 6.9 nm. The aptamer sequences were incorporated into the closed loops extending out of the ends of the helices. Apt-A is fixed on helix 1 and apt-B is moved between helix 2 and helix 5, generating the varying inter-aptamer distances but keeping the relative orientations constant. Numbering of the helices in the tile is read from left to right.

The multi-helix DNA tile was designed and constructed from either a fourhelix bundle (4HB) structure19 or a five-helix bundle (5HB) structure (generated by narrowing an eight-helix bundle tile19) that are modified with the closed-loop aptamer sequences extending out from the ends of the helices (Fig. 1b). The spacing between the two aptamers can be controlled at a subnanometer precision. For example, the 5HB DNA tile can provide 2, 3.5, 5.3 and 6.9 nm inter-aptamer distances. This was accomplished by integrating apt-A into helix 1 (the left-most helix) and moving apt-B from helix 2 to 5 (to the right). The relative axial orientation of the two aptamers was kept the same at all inter-aptamer distances.

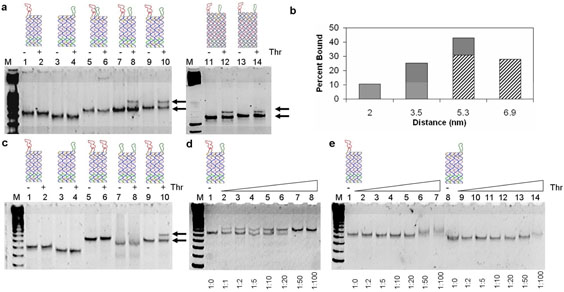

We used gel-mobility shift assays to reveal the optimal spacing between apt-A and apt-B for bivalent binding. Due to the smaller size of 4HB tiles, the 4HB tile based bivalent aptamers when bound with the thrombin would give a more obvious mobility shift in gel electrophoresis, compared to that of the 5HB tiles. The 4HB tiles carrying aptamers at various spacings (2, 3.5 and 5.3 nm intervals) were incubated with and without thrombin (40 nM protein, [DNA tile]:[protein] = 1:2) before they were analyzed using non-denaturing PAGE (see methods and Supplemental Information).

The 4HB tile containing only apt-A on helix 1 (4HB-A1) and the 4HB tile containing only apt-B on helix 4 (4HB-B4) serve as controls, which both show no slower migrating band when incubated with thrombin (Fig. 2a lanes 1-4) at this concentration. The dissociation constants (KD) of these two aptamers with thrombin have been determined to be a sub-nM or 75–100nM,15,16 respectively. There are also variations of the KD in literature depending on the different methods used15,16,20. In the gel mobility assay, the binding complexes are at nonequilibrium while migrating through the gel, so that the apparent dissociation constant KD measured here is expected to be much larger than the solution KD measured under equilibrium conditions. This can explain the observed low affinity of these two aptamers acting alone.

Figure 2. Gel-mobility shift assays.

a, Nondenaturing (8% polyacrylamide) PAGE image of aptamers linked on the 4HB and 5HB tiles. Lane M corresponds to a 25bp DNA marker. Lanes 1 to 14 correspond to 4HB-A1, 4HB-B4, 4HB-A1- B2 (2 nm), 4HB-A1-B3 (3.5 nm), 4HB-A1-B4 (5.3 nm), 5HB-A1-B4 (5.3nm), and 5HB-A1-B5 (6.9 nm), each 20 nM without (−) and with (+) thrombin (40 nM), respectively. The lower band in each lane represents the unbound tiles and the upper band in lane 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 represents the tile/thrombin complex. b, The dependence of protein binding on the inter-aptamer distance. Here 20 nM 4HB or 5HB tiles containing both apt-A and apt-B with varying distances were incubated with 40 nM thrombin before they were loaded into the gel. The 16 percentages of bound DNA tiles were estimated from the relative intensity of the bands in the gel image shown in panel a. The filled bar and striped bars are data from the 4-HB and 5-HB tiles respectively. c, The binding of thrombin to the 4HB tile-based aptamer structures carrying one aptamer or two of the same or different aptamers. All tiles with two aptamers have the same inter-aptamer distance at 5.3 nm. Lane M corresponds to a 25 bp DNA marker. Lanes 1, to 10 correspond to 4HB-A1, 4HB-B4, 4HB-A1-A4, 4HB-B1-B4, and 4HB-A1-B4 without (−) and with (+) thrombin (40 nM). An upper band is only observed in lane 10 with 4HB-A1-B4 (same as lane 10 in panel a). d, Titration experiment showing more DNA tiles (4HB-A1-B4, 1 nM) are bound to the protein with increasing concentrations of thrombin. Lane M corresponds to a 25 bp DNA ladder. From this gel a 10 nM apparent KD is estimated for the bivalent binding of thrombin to the two aptamers linked by a DNA tile at a 5.3 nm distance. e, Titration experiment for 4HB-A1 (lanes 1-7) and 4HB-B4 (lanes 8-14). Lane M is a 25 pb DNA ladder. From this gel, the apparent KD for the two individual aptamers on the 4HB tile are estimated to be 20-50 nM and > 50 nM, respectively.

For the tiles carrying two different aptamers, when incubated with thrombin, at a distance of 2 nm (4HB-A1-B2), a very faint significantly slower migrating band shows up, representing a small population of the DNA structure binding to thrombin (Fig. 2a lanes 5 and 6). From the significant lagging position of the band, we propose that in this binding complex, each thrombin molecule is sandwiched by two aptamers from two individual tiles.21 At a distance of 3.5 nm (4HB-A1-B3), another distinct upper band appears closely above that of the DNA tiles. We propose that this band is due to the binding of one thrombin molecule by the two different aptamers on the same DNA tile (Fig. 2a lanes 7 and 8), i.e. the bivalent binding. It is estimated from the relative intensities of the upper and lower bands that ~ 25% of the structure is bound to thrombin. At a distance of 5.3 nm (4HB-A1-B4), the relative intensity of this band increases, and ~ 40% of the structure is bound with thrombin (Fig. 2a lanes 9 and 10). Further, we used 5HB to generate a 6.9 nm spacing between the aptamers. Gel mobility shift assay (Fig. 2a lanes 11-14) showed a decreased binding at 6.9 nm spacing (5HB-A1-B5) compared to at 5.3 nm (5HB-A1-B5). Since the size of the thrombin protein is ~ 4 nm, we did not expect to see improved binding at any larger distances > 6.9 nm.

The percent of protein-bound DNA tiles at the different spacings were estimated based on the gel shift assay in Fig 2a, and plotted in Fig 2b. It is noted that, for the same distance arrangements (5.3 nm), the thrombin binding affinity of the bivalent aptamers on 5HB was slightly lower than that on 4HB. This difference is possibly due to the effect of an extra helix on the 5HB tile that might limit the rotational freedom of the aptamer on the 4th helix. Overall, the interaptamer distance at 5.3 nm was determined to be optimal for the bivalent binding (Fig. 2b)

As a control experiment to show that only hetero-aptamers can give such bivalent binding capability, we compared the binding of the tile containing two same aptamers arranged at the same 5.3 nm distance, 4HB-A1-A4 and 4HB-B1- B4, with the tile containing two different aptamers (4HB-A1-B4). As shown in Fig. 2c, only the tile with the hetero-aptamers displays an upper band when incubated with thrombin (lane 10). The homo-dimers did not show any significant binding, similar to the monomers. This result clearly indicated that the increased binding affinity is not caused by the increase in the number of aptamers per structure, but rather because of the type of aptamers that have a bivalent binding capability. We believe this binding on the two hetero-aptamers is that they act together like a pair of pincer to grab the same thrombin molecule each attach to a different site on the protein. Indeed, such nano-pincers are able to bind thrombin tightly and drop its load triggered by an external chemical signal, i.e. by adding the oligonucleotide complementary to the aptamer sequences (Fig. S10).

One unique feature in our aptamer loop design is that we added four thymine bases (see Supplementary Information) at the end of the stems on both strands of the helix, thereby increasing their 3-dimensional flexibility. Both aptamer sequences are known to have a stem/binding region, utilizing only a few bases for contact with the surface of thrombin.13 In order to find an optimal relative orientation of the two aptamers, we tried to rotate apt-B on the 4HB-A1- B4 by 90° and 180° by adding three or six base pairs to the stem, respectively. Both show a slight decrease in binding efficiency (Fig. S2) in comparison to the original design of 4HB-A1-B4 (Fig. 2d), however no obvious difference between these two structures was observed. We propose that the 3- dimensional flexibility provided by the TTTT on the stems enables both aptamers to rotate in a limited range that can compensate small changes in the center-to-center distances between the two aptamers so that bivalent binding efficiency can be maximized.

A rough estimate of the binding affinity of 4HB-A1-B4 to thrombin was obtained by titration of the thrombin concentration in the gel mobility shift assay (Fig. 2d lanes 1-8), a KD of ~ 10 nM was obtained (see Supplementary Information and Methods). This is about 10 fold increase in affinity compared to those of the individual apt-A or apt-B on 4HB (4HB-A1 and 4HB-B4, in Fig. 2e lanes 1-14), whose KD was estimated to be 20-50 nM and > 50 nM, respectively. These titration results confirmed the bivalent binding of the hetero-aptamers placed at the optimized distance can have a binding affinity better than any of the monovalent binding.

We also try to adapt a solution based method previously developed to measure the binding affinity of the aptamer to thrombin using molecular aptamer beacon (MAB)20. A KD of the 15-mer MAB was reported as 5.2 nM20. Using the same MAB, we observed effective displacement of the thrombin from the MAB by the 4HB-tile based bivalence aptamer 4HB-A1-B4 (see Supplementary Information). From this displacement experiment, we estimate that the tile-based bivalence aptamer binds to thrombin about ~ 50 fold stronger than the 15-mer aptamer does, thus has a solution KD of ~ 0.1 nM.

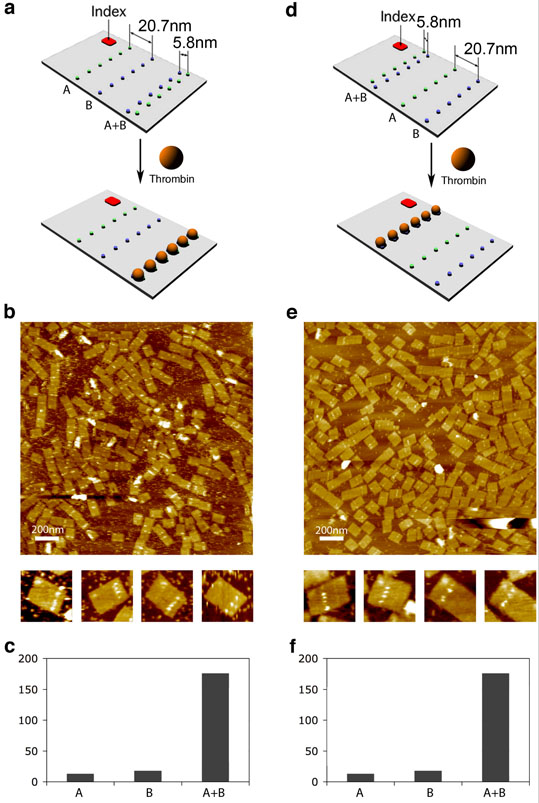

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was also used to study the bivalent binding of these two aptamers at the single molecular level. Using the DNA origami method9,11 we designed a rectangular-shaped DNA tile (Fig. 3a) that had a dimension of 60 × 90 nm. Stem-loops with apt-A and apt-B sequences were designed to protrude out of the plane of the DNA origami tile. We put two lines of each aptamer (totally four lines of aptamer probes) on the DNA origami tile, with a distance of ~ 20.7 nm and ~ 5.8 nm between the neighboring lines of apt-A and apt-B, and a intra-line distance of ~ 12 nm for the same aptamer. Based on the estimated KDs, when we add a 1:4 ratio of thrombin to the total number of aptamers, no or low binding is expected on the lines that are further apart, while stronger binding is expected on the bivalent dual-aptamer lines (marked as A+B in Figure 3a). A group of 6 closely-placed dumb-bell loops that provide a height contrast under AFM imaging was positioned in one corner of the tile as a topographic index reference to unambiguously determine the relative positions of each aptamer line.

Figure 3. Evaluation of bivalent binding by AFM.

a, d, schematic drawings of two rectangular-shaped DNA origami tiles containing two lines of apt-A (green dots) and two lines of apt-B thrombin (blue dots). The neighboring lines of apt-A and apt-B are ~ 20.7 nm (marked line A and line B) and ~ 5.8 nm (line A+B) apart. We call the closely spaced lines the dual-aptamer line. An index is also included helping to verify the positions of the lines in the AFM images. b, e, AFM height 17 images of the DNA origami tiles (10nM) with 60 nM thrombin, corresponding to a and d, respectively. Zoom-in images are 150nm × 150nm. c, f, Charts of numbers of proteins binding on each aptamer line (observed from 60 arrays corresponding to a and d respectively). Bar A represents the number of proteins on the line of apt-A, bar B represents the number of proteins on the line of apt-B, and bar A+B represents the number of proteins on the bivalent dual aptamer line.

To rule out the possibility of positional effects due to electrostatic repulsion between the probes and the DNA scaffold12, the positions of the dual-aptamer lines were switched from close to one side of the tile to the middle on another DNA origami tile (Fig. 3d). AFM images (Fig. 3b, 3e) showed that thrombin preferred to bind to the dual aptamer lines on both DNA origami tiles. Individual protein molecules can be distinctly detected. We counted the number of protein molecules bound to each aptamer line (Fig. 3c, 3f). The dual-aptamer line shows a ~10 fold better protein binding than the single aptamer lines, consistent with the gel assay results.

Whitesides et al.1 previously pointed out that “the more conformationally rigid the polyvalent entity is, the more likely it is that even small spatial mismatches between the ligand and its receptor will result in enthalpically diminished binding (unless the geometric fit between ligand and receptor is accurate at a picometer scale, which is exceedingly rare)”. Here we have a rigid scaffold that has spatial accuracy at the nanometer scale, thus enthalpically diminished binding due to small spatial mismatches between the aptamers and thrombin is unavoidable, while limited conformational flexibility will help to compensate this small spatial mismatch at a cost of certain entropy loss. Nevertheless, the trend of distance dependent effect on multivalent binding observed here at this spatial resolution is very interesting.

This study also represents the first example of utilizing the spatial addressability of self-assembled DNA nanoscaffolds to control multi-component biomolecular interactions and visualizing such interactions at a single molecule level. In addition to aptamers, one may be able to position small peptides22, subdomains and cofactors of enzymes, or carbohydrate molecules into 2D and 3D spatially controlled networks to obtain multivalent behavior, which may be used to probe sterical constraints, ionic interactions and hydrophobic interactions. It may also be possible to use addressable DNA nanoscaffolds5-10,12,13,23 to position motor proteins at a particular inter-molecular distance to display complex motor behaviors on a well-defined nanometer scale landscape on the DNA nanoscaffold generated by modifying the staple strands of the origami at different locations.

Methods

Thrombin binding and gel-shift assay

All oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology Incorporated (www.idtdna.com) and 10 purified by 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). See Supplementary Information for a complete list of oligonucleotides used. The concentration of each strand was measured by OD260. Each individual tile was assembled by mixing each strand to a final concentration of 1.0 µM per strand, and annealed using an Eppendorf thermo-cycler starting at 90°C and decrease by 0.4°C per min to 24°C. The tiles were further diluted for thrombin binding and gel-shift assays. Human α-thrombin was purchased from Haematologic Technologies Incorporated (www.haemtech.com). The concentration was estimated at OD280. All buffers used in the experiments contained 100 mM Tris, 50 mM acetic acid, 5 mM EDTA, and 12.5 mM magnesium acetate. 4HB and appropriate aptamers were incubated with specified amounts of thrombin for 1 hour at room temperature. Non-denaturing PAGE was run on Amersham Ruby- 600 at a constant 200 V for 4 hours (for 8% gels) or 12 hours (for 6% gels) and stained with SybrGold (Invitrogen, 1× dye in 100 mL water) or SybrGreen (Invitrogen, 1× dye in 100 mL water). Gels were imaged with the Epichem3 Darkroom gel documentation system (UVP BioImaging Systems) and band intensity was densitometrically measured with Labworks software or with Image J (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

AFM Imaging

Rectangular-shaped DNA origami tiles were assembled according to Rothemund's method.9 Helper strands modified with aptamer sequences were purified using denaturing PAGE and mixed with the viral DNA and the unmodified helper strands at a molar ratio of 1:1:5. Each array contains 24 thrombin binding aptamers (12 apt-A and 12 apt-B). Arrays (10 nM) were 11 mixed with thrombin (60 nM, or 1:1 ratio of the dual-aptamer to thrombin) for 1 hour before imaging. The sample (2 μL) was deposited onto a freshly cleaved mica cell (Ted Pella, Inc.) and left to adsorb for 3 min. 1ΧTAE/Mg buffer (400 μL) was added to the liquid cell and the sample was scanned in a tapping mode under fluid on a Pico-Plus AFM (Molecular Imaging, Agilent Technologies) with NP-S tips (Veeco, Inc.). Low concentrations of protein were also imaged (supplemental Fig. S5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was derived from a discussion of synthetic antibody project with Stephen A. Johnston at the Biodesign Institute at ASU. We also thank Stuart Lindsay, Chris Diehnelt and Dong-Kyun Seo for helpful discussions. S.R. was partly supported by TRIF funds from ASU to S.A.J. This work was partly supported by grants from NSF, NIH, AFOSR and ONR to H.Y and ASU startup fund to Y.L.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interest statement: Authors declare no competing financial interests for this work.

References

- 1.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Polyvalent interactions in biological systems: implications for design and use of multivalent ligands and inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2755–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Giusto DA, King GC. Construction, stability, and activity of multivalent circular anticoagulant aptamers. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46483–46489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredriksson S, et al. Protein detection using proximity-dependent DNA ligation assays. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pei R, et al. Behavior of polycatalytic assemblies in a substrate-displaying matrix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12693–12699. doi: 10.1021/ja058394n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothemund PWK, Papadakis N, Winfree E. Algorithmic self-assembly of DNA sierpinski triangles. PloS Biology. 2004;2:2041–2053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund K, Liu Y, Lindsay S. Self-assembling a molecular pegboard. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17606–17607. doi: 10.1021/ja0568446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Ke YG, Yan H. Self-assembly of symmetric finite-size DNA nanoarrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17140–17141. doi: 10.1021/ja055614o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SH, et al. Finite-size, fully addressable DNA tile lattices formed by hierarchical assembly procedures. Angew. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:735–739. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothemund PWK. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature. 2006;440:297–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pistol C, Dwyer C. Scalable, low-cost, hierarchical assembly of programmable DNA nanostructures. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:125–305. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chhabra R, Sharma J, Ke Y, Liu Y, Rinker S, Lindsay S, Yan H. Spatially addressable multiprotein nanoarrays templated by aptamer-tagged DNA nanoarchitectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10304–10305. doi: 10.1021/ja072410u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ke Y, Lindsay S, Yung C, Liu Y, Yan H. Self-assembled water soluble nucleic acid probe tiles for label-free RNA hybridization assays. Science. 2008;319:180–183. doi: 10.1126/science.1150082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng JW, et al. Two-dimensional nanoparticle arrays show the organizational power of robust DNA motifs. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1502–1504. doi: 10.1021/nl060994c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nimjee SM, Rusconi CP, Sullenger BA. Aptamers: an emerging class of therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005;56:555–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasset DM, Kubik MF, Steiner W. Oligonucleotide inhibitors of human thrombin that bind distinct epitopes. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:688–698. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Selection of single-stranded-DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin. Nature. 1992;355:564–566. doi: 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padmanabhan K, Padmanabhan KP, Ferrara JD, Sadler JE, Tulinsky A. A. The structure of alpha-thrombin inhibited by a 15-mer singlestranded-DNA Aptamer. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:17651–17654. doi: 10.2210/pdb1hut/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stubbs MT, Bode W. The clot thickens: clues provided by thrombin structure. Trends Biochem. 1995;20:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88945-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ke Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Yan H. A study of DNA tube formation mechanisms using 4-, 8-, and 12-helix DNA nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4414–4421. doi: 10.1021/ja058145z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Fang X, Tan W. Molecular aptamer beacons for real-time protein recognition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2002;292:31–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Lin C, Li H, Yan H. Aptamer-directed self-assembly of protein arrays on a DNA nanostructure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4333–4338. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams BAR, Lund K, Liu Y, Yan H, Chaput JC. Self-assembled peptide nanoarrays: an approach to studying protein-protein interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3051–3054. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tumpane J, et al. Triplex addressability as a basis for functional DNA nanostructures. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3832–3839. doi: 10.1021/nl072512i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.