Abstract

Background

Ethics consultation is used regularly by some doctors, whereas others are reluctant to use these services.

Aim

To determine factors that may influence doctors to request or not request ethics consultation.

Methods

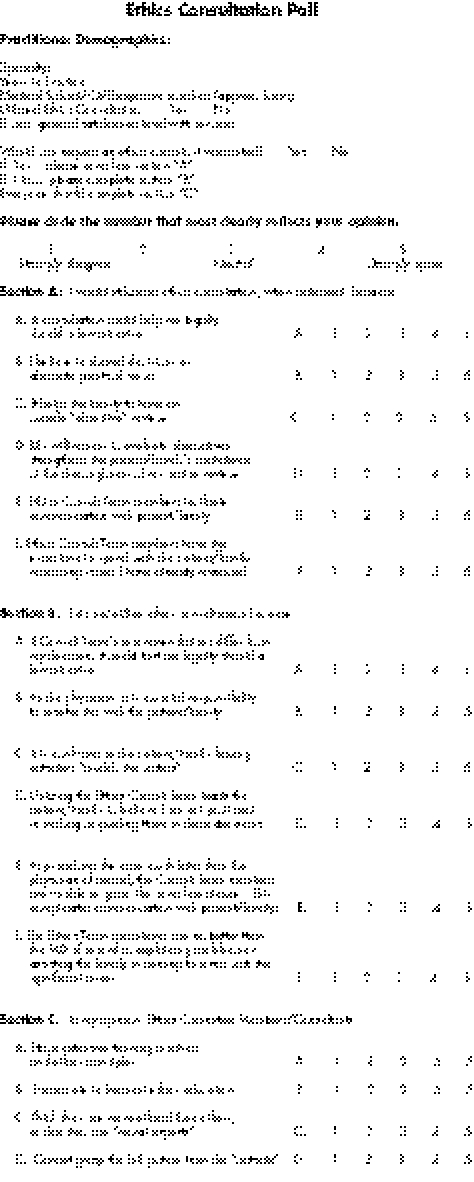

A survey questionnaire was distributed to doctors on staff at the University Community Hospital in Tampa, Florida, USA. The responses to the questions on the survey were arranged in a Likert Scale, from strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree to strongly agree. Data were analysed with the Wilcoxon test for group comparisons, the χ2 test to compare proportions and a logistic regression analysis.

Results

Of the 186 surveys distributed, 121 were returned, giving a 65% response rate. Demographic data were similar between the groups saying yes (I do/would use ethics consultation when indicated) and no (I do not/would not use ethics consultation when indicated). No statistically significant differences were observed between the user and non‐user groups in terms of opinions about ethics consultants having extensive training in ethics or participating in ethics educational opportunities. On the issue “Ethics committee members or consultants cannot grasp the full picture from the outside”, the non‐users were neutral, whereas the users somewhat disagreed (p = 0.012). Even more significant was the difference between surgeons and non‐surgeons, where, by logistic regression analysis, surgeons who believed that ethics consultants could not grasp the full picture from the outside were highly likely to not use (p = 0.0004). Non‐users of ethics consultations thought that it was their responsibility to resolve issues with the patient or family (72.2% agree, p<0.05). Users of ethics consultation believed in shared decision making or the importance of alternate points of view (90.8% agree, p<0.05).

Implications

Ethics consultations are used by doctors who believe in shared decision making. Doctors who did not use ethics consultation tended to think that it was their responsibility to resolve issues with patients and families and that they were already proficient in ethics.

Much has been written about ethics consultation,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 but little has been written about why some doctors choose to use ethics consultation, whereas others rarely, if ever, avail themselves of it.21,22 Ethics consultation has been codified into law in various states through court opinions, beginning with the Karen Ann Quinlan case23 and progressing through the Maryland laws that protect those providing ethics consultation.24 The American Medical Association recognised ethics consultation when it provided a specific DRG code for it in 1994.25 It is widely recognised that some doctors frequently use ethics consultation, sometimes excessively, whereas others are reluctant or refuse to request it. The reasons for these variations have not been studied. This study was undertaken to attempt to answer some of the questions on why some doctors use ethics consultation while others refuse.

Methodology

A questionnaire (appendix) was developed with two parts, one for doctors who used ethics consultation and the other for those who did not. The questionnaire was distributed to all doctors in the sample and they were asked to choose the part of the questionnaire that most applied to their circumstances. The questionnaire was distributed at a General Medical Staff meeting. The doctors were promised anonymity in their responses, and either turned in the completed questionnaire at the meeting, or faxed it back to a response number.

The questionnaire was designed on a 5‐point Likert Scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The original idea behind the two‐part questionnaire was to ensure honest answers to the questions by allowing the questions to be phrased in a positive manner on either section of the questionnaire. If doctors chose the “Yes I have” or “would use” ethics consultation section of the questionnaire, they were asked to rank statements such as “consultation could help me legally should a lawsuit arise”, “I believe in shared decisions or alternate points of view” or “It helps the family to have an outside ‘objective' review” on a 5‐point Likert Scale. If doctors chose the “No, I have not” or “would not” use ethics consultation part of the questionnaire, they were asked to rank similar, but oppositely worded statements such as “If the Ethics Consult Team's recommendations differ from my decision, it could hurt me legally should a lawsuit arise”, “As the physician, it is my total responsibility to resolve this with the patient/family”, or “It is confusing to the patient/family having outsiders ‘muddy the waters'”. As such, both groups of respondents would be answering in the affirmative for opposite reasons if they agreed with the statements. Both groups were also asked to evaluate the same four statements about the background and training of ethics committee members.

Data were statistically analysed with the Wilcoxon test for group comparisons, the χ2 test to compare proportions and logistic regression analysis.

The University Community Hospital, Tampa, Florida, USA, is a 431‐bed community hospital with more than 25 000 inpatient admissions every year and 746 doctors, or staff, with admitting privileges. The ethics committee conducts 55–75 ethics consultations every year, with four ethics consult teams rotating call each week. Each ethics consult team consists of a doctor, a nurse, a social worker and an additional member who is a dietician, chaplain, community member or other ethics committee member. Ethics consultation has been in place since 1994. The ethics committee and the institutional review board approved this study.

Results

Of the 186 surveys distributed, 121 (65%) were returned, of which 98 were users and 23 were non‐users. Demographic data were similar between the user and non‐user groups. The non‐users of ethics consultation had been in practice for longer than the users (mean 16.5 years v 14.2 years; p = 0.332). Non‐users reported more hours of medical school or continuing medical education exposure to ethics than did users of ethics consultation (72.8 h v 25.9 h; p = 0.353). No significant differences were evident between the user and non‐user groups in terms of opinions about ethics consultants having extensive training in ethics or participating in ethics educational opportunities, with both groups somewhat agreeing or neutral.

Both users and non‐users of ethics consultation disagreed that ethics consultants were more ethical or moral experts. The only significant difference in the general questions between the users and non‐users of ethics consultation was their response to the statement “Ethics committee members or consultants cannot grasp the full picture from the outside”. To this statement, the non‐users were neutral, whereas the users somewhat disagreed (p = 0.012). Even more significant was the difference between surgeons and non‐surgeons to this statement. By logistic regression analysis, surgeons who believed that ethics consultants could not grasp the full picture from the outside were highly likely to not use ethics consultation (p = 0.0004). This was the only area where surgeons significantly differed from non‐surgeons.

In terms of the statements that were worded slightly differently depending on whether the respondent would or would not use ethics consultation, the non‐users most often believed that it was their responsibility to resolve the issues with the patient or family. This was the only response from more than 50% of non‐users that was in the affirmative (72.2% agree, p<0.05). The other significant response from non‐users was a negative response to whether using the ethics consult team would lead the patient or family to believe that the doctor is not effective in helping or guiding them with their decisions (only 27.8% agree, p<0.05).

For users of ethics consultation, all responses had greater than 50% agreement. The one statement that was significantly chosen over the others was that the doctor believed in shared decisions or alternate points of view (90.8% agree, p<0.05). Other questions that were highly agreed on were that ethics consultation helps the family to have an outside objective review, that ethics consultation strengthens the patient's or family's confidence in the thoroughness of the doctor's review of options and that it facilitates communication with patients and families. Lower mean responses were obtained for the statements that ethics consult team members have extra time to spend with the patient or family and that an ethics consultant could help legally should a lawsuit arise (p<0.05 compared with other responses).

Discussion

Only anecdotal information has been published in the past on the factors that influence a doctor's use of ethics consultation.21,22 This study is the first attempt to quantify and directly assess these factors.

Ethics committees have been in existence since the early 1970s.5 In 1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court (In re Quinlan) formally recognised ethics consultation when it recommended a “prognosis committee” as a means to making decisions on the withdrawal of life support from terminally ill people.23 In 1980, the American Board of Internal Medicine began including questions on medical ethics in its certification exam.26 In 1983, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioural Research in its report,27Deciding to forego life‐sustaining treatment, recommended exploring and evaluating the use of ethics committees, particularly for decisions that have life‐or‐death consequences. In 1985, the American Medical Association's Judicial Council published guidelines on ethics committees in hospitals.6 In 1986, the New York State Task Force on Life and the Law encouraged resolving dilemmas on patient care at the hospital level rather than by turning to the courts, and suggested that ethics committees may mediate such disagreements.28 In 1993, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations29 adopted a policy requiring accredited hospitals to have in place a process such as an ethics committee or ethics consultation service for resolving ethical dilemmas. Ethics consultation has been shown to be effective in clarifying ethical issues,9,16,17,18,19,20 resolving ethical dilemmas,8,16,17,20 and defining ethical problems not previously recognised.9,16,17,18,19,20 Despite ethical issues permeating clinical practice, clinicians do not often request ethics consultation.

Only two previous articles have attempted to deal with the issue of why doctors do or don't use ethics consultation.21,22 Davies and Hudson21 conducted an exploratory, qualitative study on ethics consultation by using open‐ended interviews of 12 doctors who were heads of departments, divisions or clinical services at a large, urban teaching facility. Seven of the doctors were in surgical specialties and five were in medical specialties. Of the 12 doctors, 10 were of the opinion that ethics consultation was not a useful tool for solving ethical dilemmas, and they did not use it. The authors of the study commented that misperceptions of medical ethics varied widely and were held by all participating doctors. Non‐users of ethics consultation (83%) generally held the position that the doctor should be the primary decision maker, that ethics consultation undermined the doctor's role, that the intrusion of an ethics committee into a doctor's interaction with a patient was not welcome and that doctors who used ethics consultation were abdicating their responsibility.21 Doctors who used ethics consultation (17%) believed in shared decision making, considered themselves to be patient advocates and found outside opinions useful in troubling or difficult cases.21 Davis and Hudson's study had several limitations. It was only a hypothesis‐generating, open‐ended interview study. Department heads at a teaching institution are probably not representative of the rank and file, although the authors chose heads of services because their opinions influence hospital policy and because their approval was required for consultation to proceed. As a result of choosing department heads, their sample consisted of older male doctors with a preponderance of surgical specialists.

Du Val et al's22 study sought to determine the triggers for clinicians' requests for ethics consultation. They used a cross‐sectional telephone survey of internal medicine physicians. Only slightly more than half of these doctors had requested ethics consultation, most commonly for ethical dilemmas related to end‐of‐life decision making, patient autonomy issues and conflicts. The most common triggers leading to requests for ethics consultation were wanting help for resolving a conflict; for interacting with a difficult family, patient or surrogate; for making a decision or planning care; and for emotional triggers such as fear, frustration or feeling uncomfortable with a situation. This study had the limitation of sampling only internal medicine physicians, predominantly oncology and critical care specialists. It did not investigate why doctors did not use ethics consultation, even though 45% of respondents had not requested ethics consultation.22

Our study also had several limitations. As we used a self‐reporting questionnaire that was anonymous, we had no way of correlating how many doctors who reported that they had or would use ethics consultation had actually requested it in the past. Our response rate was modest, although not bad for a single distribution of a questionnaire. By using two questionnaires worded oppositely to investigate the same issues, we created some problems for statistical analysis, which may have limited the statistical significance of some items on the questionnaire.

We made several interesting observations. Many of the doctors on staff at the University Community Hospital have office‐based practices and do not see patients in the hospital. They therefore do not use or have not had the opportunity to use the services of ethics consult teams, although ethics consultations are provided for office‐based issues. Of the 98 practitioners from the user group, 61 or 64% were medical and 34 were surgical (3 did not answer this question). Of the 23 from the non‐user group, 13 were medical and 10 were surgical. An identical percentage of respondents had been in practice for more than 10 years for both the user and non‐user groups (67%). Only 35% of users and 13% of non‐users had previously used ethics consultation. Of the users, 88% who had used ethics consultation had a good, very good or excellent opinion of the service, with 9% not answering the question and only one respondent grading the service as fair. In contrast, 20 of the 23 non‐users had never ordered ethics consultation, and of the three who had ordered ethics consultation, two considered the service excellent.

About a quarter of the users and non‐users reported more than 10 h of medical school or exposure to ethics, but non‐users of ethics consultation reported almost three times as many hours of educational exposure to ethics as users of ethics consultation (mean 72.8 h v 25.9 h; p = 0.353). Whether this means that non‐users of ethics consultation did not feel the need for ethics consultation because they already felt competent in this area cannot be answered with certainty. One of the questions answered most strongly on the non‐user survey was question D, which stated, “Utilizing the Ethics Consult Team leads the patient/family to believe I am not proficient in making or guiding them in these decisions”. More non‐user respondents answered this question with a “strongly disagree” than any other question. The other question on the non‐user survey that may reflect ethics knowledge was question F, which stated, “The Ethics Team consultants are no better than the MD of record in explaining problems or assisting the family in coming to terms with the significant issues”. For this question, most responses were neutral or left blank. Likewise, another opinion sought from both users and non‐users was whether “Ethics Committee Members/Consultants think they are more ethical than others, or that they are moral experts”, and here the non‐users strongly disagreed or disagreed in 34% of responses, were neutral in 17%, and gave no answer in 39%. Both groups of respondents were also asked whether they believed “Ethics Committee Members/Consultants have extensive training in ethics and ethics principles”, and here again most non‐users were neutral or did not respond, 23% agreed or strongly agreed and 19% disagreed or strongly disagreed. From the response to these questions it does not seem that non‐users of ethics consultation believe they are already ethics experts and do not need the help of ethics consultation. On the other hand, the responses of the non‐users were distinctly different from those of users of ethics consultation on this last question. On whether they believed that “Ethics Committee members/consultants have extensive training in ethics and ethics principles”, more than half (51%) the users agreed or strongly agreed with this statement and 35% were neutral, whereas only 23% of the non‐users agreed or strongly agreed and 26% were neutral. It is therefore possible that some non‐users believe they do not need the help of ethics consultation because they already feel proficient in this area.

We had hypothesised that older doctors and surgeons would be less likely to use ethics consultation, but that was not what we found. We found no statistically significant difference between users and non‐users of ethics consultation in terms of number of years in practice or of medical or surgical practice specialty. The only area where surgeons significantly differed from non‐surgeons was on the question about ethics consultants not being able to grasp the full picture from the outside. The surgeons who agreed with this position were highly unlikely to use ethics consultation.

Non‐users of ethics consultation most often believed that it was their responsibility to resolve the ethical issues with the patient or family. On the other hand, they did not think that using ethics consultation would lead the patient or family to believe that the doctor was not competent in helping or guiding them with their decisions. Apparently, non‐users of ethics consultation believed that they had both the capability and the responsibility to independently resolve ethical issues with the patient or family. They believed that they alone could fully grasp all of the ramifications of the ethical issues, and that it was either unfair or unrealistic to expect an outsider in the guise of an ethics consultant to be able to fully comprehend and appreciate the entire picture.

Users of ethics consultation, on the other hand, believed strongly in joint or shared decision making and that they had a responsibility to entertain alternate points of view. They believed that an outside, objective review of the issues was beneficial to the patient and family, and that ethics consultation strengthened the patient's or family's confidence in the doctor and the thoroughness of his review of all of the options. They believed that ethics consultation improved communication with the patient and family.

Our study differs from the report of Davies and Hudson21 in several important ways. Most respondents in their study21 were non‐users (83%) of ethics consultation and 58% were surgeons, whereas in our study most (81%) were users of ethics consultation and only 37% were surgeons. The Davies and Hudson study21 was largely negative on the use of ethics consultation, with most doctors believing that ethics consultation was not a useful tool for solving ethical dilemmas and was therefore not used. The doctors in their study believed that it was their primary responsibility to be the decision maker, and regarded ethics consultation as an intrusion into the doctor–patient relationship, resulting in a loss of control over the doctor–patient interaction, and considered it an abdication of their responsibility to make decisions on behalf of patients. Most doctors in our study professed a belief in shared decision making and valued alternate points of view. They believed that an objective review of the issues by an outside consultant was beneficial for all concerned. Their experience with ethics consultation suggested that it strengthened the patient's and family's confidence in their doctor by confirming that the doctor had thoroughly reviewed all options. They also believed that ethics consultation facilitated communication with families and patients rather than complicating it or impeding it.

In conclusion, doctors who use ethics consultation do so because they believe in shared decision making. They do not differ from non‐users in terms of specialty, years in practice or exposure to ethics education. Doctors who do not use ethics consultation tend to believe that it is their responsibility to resolve issues with patients and their families. Surgeons and non‐users of ethics consultation are of the opinion that ethics committee members and consultants cannot possibly grasp the full picture from the outside. Some non‐users believe that they do not need help because they are already proficient in ethics.

APPENDIX

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Cranford R E, Doudera A E. The emergence of institutional ethics committees. Law Med Health Care 19841213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purtilo R B. Ethics consultations in the hospital. N Engl J Med 1984311983–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine C. Questions and (some very tentative) answers about hospital ethics committees. Hastings Cent Rep 1984149–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fost N, Cranford R E. Hospital ethics committees: administrative aspects. JAMA 19852532687–2692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosner F. Hospital medical ethics committees: a review of their development. JAMA 19852532693–2697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AMA Judicial Council Guidelines for ethics committees in health care institutions. JAMA 19852532698–2699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo B. Behind closed doors: promises and pitfalls of ethics committees. N Engl J Med 198731746–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan T A. Ethics committees and decisions to limit care: the experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. JAMA 1988260803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins H S, Saathoff B S. Impact of medical ethics consultations on physicians: an exploratory study. Am J Med 198885761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skeel J D, Self D J. An analysis of ethics consultation in the clinical setting. Theor Med 198910289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iserson K V, Goffin F B, Markham J J. The future functions of hospital ethics committees. HEC Forum 1989163–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer P A, Pellegrino E D, Siegler M. Ethics committees and consultants. J Clin Ethics 19901263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno J. Ethics consultation as moral engagement. Bioethics 1991544–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swenson M D, Miller R B. Ethics case review in health care institutions. Arch Int Med 1992152694–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West M B, Gibson J M. Facilitating medical ethics case review: what ethics committees can learn from mediation and facilitation techniques. Camb Q Healthcare Ethics 1992163–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaPuma J, Stocking C B, Darling C M.et al Community hospital ethics consultation: evaluation and comparison with a university hospital service. Am J Med 199292346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orr R D, Moon E. Effectiveness of an ethics consultation service. J Fam Pract 19933649–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orr R D, Morton K R, deLeon D M.et al Evaluation of an ethics consultation service: patient and family perspective. Am J Med 1996101135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClung J A, Kamer R S, DeLuca M.et al Evaluation of a medical ethics consultation service: opinions of patients and health care providers. Am J Med 1996100456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowdy M D, Robertson C, Bander J A. A study of proactive ethics consultation for critically and terminally ill patients with extended lengths of stay. Crit Care Med 199826252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies L, Hudson L D. Why don't physicians use ethics consultation? J Clin Ethics 199910116–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuVal G, Sartorius L, Clarridge B.et al What triggers requests for ethics consultations? J Med Ethics 200127(Suppl 1)i24–i29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.In re Quinlan 70 N.J. 10, 54–5, 335 A. 2d 647, 671–2 1976

- 24.Md Health Gen. Code Ann. Sections 19–370 to 19–374—Maryland Patient Care Advisory Committee Act. 1987

- 25.AMA Council on Medical Service Payment for ethics consultations. Resolution 115, I‐93. Report 16 (adopted 12 June 1994)

- 26.Sulmasay D P, Geller G, Levine D M.et al Medical house officers' knowledge, attitudes and confidence regarding medical ethics. Arch Int Med 19901502509–2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research Deciding to forego life‐sustaining treatment: ethical, medical and legal issues in treatment decisions. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1983

- 28.New York State Task Force on Life and the Law Do not resuscitate orders: the proposed legislation and report of the New York State Task Force on Life and the Law. April 1986. New York State; Albany, New York

- 29.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Patients' rights and organizational ethics. In: Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals. Chicago: JCAHO, 199566 Chicago, Illinois