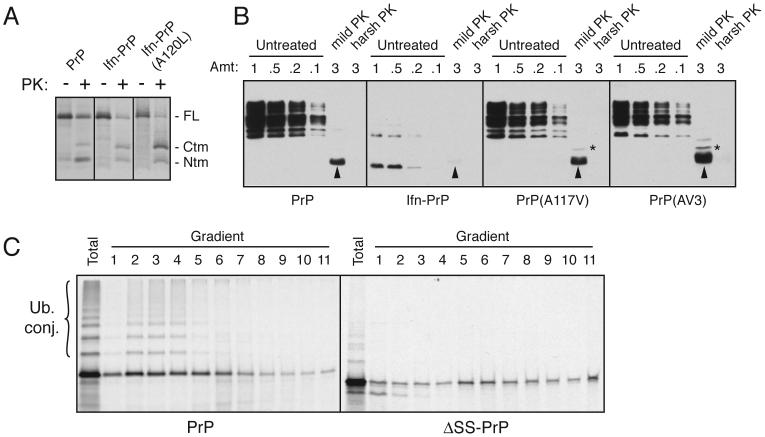

Fig. 3. Ifn-PrP metabolism is distinct from CtmPrP and ΔSS-PrP.

(A) Wild type PrP, Ifn-PrP, and Ifn-PrP(A120L) were analyzed by in vitro translation and translocation assays. An inhibitor of glycosylation was included in all reactions to simplify the banding pattern. Half of each sample was analyzed directly, while the remainder was digested with PK. The positions of full length (FL) PrP, and the proteolytic fragments corresponding to CtmPrP and NtmPrP are indicated. Note that Ifn-PrP makes comparable amounts of CtmPrP as wild type, while Ifn-PrP(A120L) makes substantially more.

(B) Wild type PrP, Ifn-PrP, PrP(A117V) and PrP(AV3) were expressed in N2a cells, and microsomes isolated from these cells were subjected to analysis for CtmPrP by limited PK digestion. Shown are different relative amounts of undigested sample, as well as the products after digestion under ‘mild’ and ‘harsh’ conditions (see Hegde et al., 1998). The PK-digested samples were deglycosylated with PNGase before analysis. In this assay, PK digestion under mild conditions generates an ∼18 kD fragment corresponding to CtmPrP (indicated by asterisk). A smaller band corresponding to the C-terminal globular domain of PrP is indicated by the arrowheads. Note that Ifn-PrP levels are very low due to its constitutive degradation (see Fig. 4B), even though its rate of expression was verified to be comparable to wild type PrP by pulse-labeling experiments as in Fig. 4A (data not shown). A band at ∼14 kD seen in the Ifn-PrP samples appears to be a degradation intermediate that is sometimes observed.

(C) PrP and ΔSS-PrP were synthesized in vitro in the absence of ER membranes and analyzed by sucrose gradient sedimentation. An aliquot of the total translation products is also shown. Note that PrP is ubiquitinated significantly more efficiently than ΔSS-PrP, and that the two proteins have different sedimentation profiles indicative of associations with different complexes.