Abstract

Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) is a project designed to reconfigure postgraduate medical education throughout the United Kingdom. It is proposed that all UK medical school graduates undertake a 2 year foundation programme to build basic professional skills to which specialist training can be added. Implicit in these proposals is that career choices need to be made at a relatively early phase of training. In the case of emergency medicine, a common stem of training in emergency and critical care is being proposed which would be suitable early training for potential specialists in emergency medicine, anaesthesia, intensive care, and acute medicine. In both foundation training and higher specialist training, the trainee should have the skills of a self directing, reflective learner and the trainer the skills required to produce a good learning environment with a supportive and open atmosphere and learning structured to maximise the opportunities for experiential learning in the workplace.

Keywords: medical education, Modernising Medical Careers, postgraduate

Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) is a project designed to reconfigure postgraduate medical education throughout the United Kingdom. It proposes that after medical school, all UK graduates should undertake a 2 year foundation programme to build the basic professional skills to which specialist training can be added. Thereafter, trainees should enter run through specialist training programmes in general practice or in a secondary care specialty leading to the award of a CCT.

Those trainees who fail to progress through training, or those trainees who cannot secure a training post, can be employed in posts whose main aim is the delivery of service but which allow professional development through experience rather than through a more formal training programme. Movement is to be possible between these service provision posts and training posts.

This is a fundamental change not only in how postgraduate medical education is delivered but also in how the service is delivered. It carries with it many changes, however the remainder of this article will concentrate on the educational implications for the emergency department.

Foundation programmes

With effect from August 2005 all UK graduates have to enter a 2 year foundation programme. The first year will be broadly equivalent to the existing PRHO year and will lead to full registration with the GMC for those who successfully complete it. Taken as a whole the foundation programme aims to:

Develop further and consolidate clinical skills particularly with respect to acute medicine so that sick patients are regularly and reliably identified and managed in whatever setting they present

Ensure that professional attitudes and behaviours are embedded in clinical practice

Validate the acquisition of competence in these areas through a reliable and robust system of assessment

Offer the opportunity for doctors to explore a range of career opportunities in different settings and areas of medicine.

Foundation year curriculum, March 2005

Whilst responsibility for the second year of foundation programmes will rest ultimately with the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB), it is likely that day to day responsibility for planning, running, and quality assuring programmes will be delegated to the Deaneries.

Most Deaneries are planning three 4 month attachments for foundation year 2 (FY2). The choice of 4 month attachment is largely driven by the need to provide experience in a greater variety of settings than before. The reason for including emergency medicine as one of these attachments is because it is widely recognised that many of the competencies listed in the curriculum, such as communication, team working, multi‐professional practice, time management, decision making, use of evidence, and high standards in clinical governance and safety, can all be delivered there.

The College of A&E Medicine and the British Association of Emergency Medicine both believe that a 6 month attachment in foundation year 2 would be the best way to meet the service needs of the A&E department and also the educational objectives of the curriculum for foundation programmes. Various patterns of foundation programmes have emerged, but the commonest is for three 4 month attachments in foundation year 2.

The philosophy of foundation programmes is that education is predominantly based in the workplace. It relies completely on the concept of a self directing, reflective, adult learner. It is imperative that the necessary skills and attributes to allow this style of learning are imparted at medical school and reconfirmed early in foundation programmes.

Experiential learning such as is proposed requires a recognition on the part of the trainer and trainee of the learning opportunities in day to day work. To maximise the benefit of these opportunities, the department should be arranged so that there are opportunities for one to one working between a trainer and trainee so that direct observation of clinical performance can be undertaken. The learning portfolio for foundation training will include a reflective log in which the trainee should be encouraged to record the outcomes of key educational experiences.

This same one to one working will also be necessary for the delivery of the assessment structure proposed for a foundation programme. These assessments are workplace based and comprise peer assessment in the form of multi‐source feedback (or 360° appraisal) and observed clinical practice in the form of mini CEX and DOPS.

The fourth assessment tool that is proposed is case based discussion. This is a dialogue between trainer and trainee about entries in the medical record left by the trainee. The interaction is designed to allow an analysis of the clinical reasoning which underpins the decisions made by the trainee.

All of these assessment tools are simply refinements of the kinds of observation and interactions between trainers and trainees that have been undertaken for centuries. Taken together, and sampling across a range of different types of cases and contexts of care, they are likely to give a reliable and valid assessment of progress against the curriculum.

Given that they are workplace based and seek to capture interactions that should already be undertaken, these assessment tools may well be feasible, but they will require an investment of time on the part of trainers.

Early drafts of the curriculum for foundation year 2 estimated that each trainee would require 4½ h of assessment over the course of the year. This is likely to be the absolute minimum time requirement.

It is imperative that this increased burden of supported learning, workplace based assessment, and appraisal is represented on a consultant's job plan.

Not all of the assessments listed above need to be undertaken by a consultant, but all who do undertake the assessments need to be trained in the application of these assessment tools. Questioning skills, listening skills, and the skills of effective feedback are essential requirements.

Higher specialist training

Implicit in the MMC proposals is that career choices need to be made at a relatively early phase of training.

A consensus is emerging, well expressed in the JDC document on specialist training of February 2005, that selection should first be into a broad area of interest. In the case of emergency medicine, that area of interest could be “acute emergency and critical care”. Trainees considering a career in a specialty in this field could undertake the first 2 years of training to acquire transferable competencies from one specialty to another within that broad field of practice. Experience within that 2 years could also allow a more refined selection, on the part of both the trainee and the specialty. However, to assist manpower planning, the trainee should make an indicative choice of final specialty at entry to common stem.

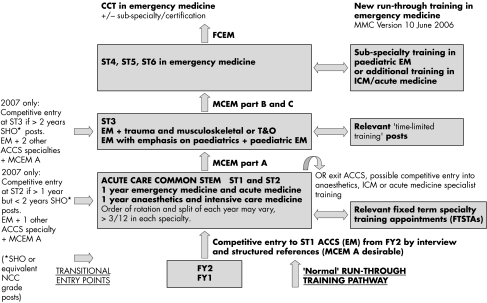

To this end, the College proposes a common stem of training in emergency and critical care which would be a suitable early training for potential specialists in emergency medicine, anaesthesia, intensive care, and acute medicine. There is an agreement in principle with the other specialties involved. Detailed work is underway to select from existing curricula those elements that usefully could be covered in such a common stem training. A diagrammatic representation of a possible career pathway in emergency medicine is shown in fig 1.

Figure 1 Proposed career pathway in A&E medicine, June 2006. FY, foundation year.

All specialties face the challenge of seeking ways to deliver, in a shorter timeframe, training to bring about the same level of performance as that currently demonstrated by a CCT holder.

This can only be delivered if the same philosophy applies to higher specialist training as is applied to foundation training, that is the trainee has the skills of a self directing, reflective learner and the trainer has the skills required to produce a good learning environment with a supportive and open atmosphere and learning structured to maximise the opportunities for experiential learning in the workplace.

The suite of assessment tools used in foundation training can also be applied in higher specialist training where the burden of workplace based assessment to inform RITA processes that a trainee is suitable to move to the next year of training will be increasingly onerous.

Once again, time and resources needed to deliver this require a committed, educationally aware trainer workforce with adequate recognition in their job plan of the time that will be required to deliver the desired outcome.