Abstract

Wild-type Desulfovibrio fructosivorans and three hydrogenase-negative mutants reduced Pd(II) to Pd(0). The location of Pd(0) nanoparticles on the cytoplasmic membrane of the mutant retaining only cytoplasmic membrane-bound hydrogenase was strong evidence for the role of hydrogenases in Pd(0) deposition. Hydrogenase activity was retained at acidic pH, shown previously to favor Pd(0) deposition.

The ability of sulfate-reducing bacteria to reduce metallic ion species is well documented, and the involvement of microbial enzymes in this process has been established. The enzymatically mediated reduction of Cr(VI), Se(VI), As(V), Tc(VII), Hg(II), and other metals by many species has been reported previously (4, 5, 12-14, 16, 20). The highest rate of Cr(VI) reduction by members of the genera Desulfovibrio and Desulfomicrobium is associated with Desulfomicrobium norvegicum (19), attributable to the Fe hydrogenase of this bacterium. The Fe hydrogenase of Clostridium pasteurianum reduces selenite (24), and the role of unspecified periplasmic hydrogenases of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans in the reduction of technetium, palladium, and uranium (6, 10-13, 15) suggests that metal reductase activity seems to be a common feature of hydrogenases.

Three hydrogenases (periplasmic NiFe hydrogenase [23] and Fe hydrogenase [1] and a cytoplasmic NADP-reducing hydrogenase [18]) have been found in Desulfovibrio fructosivorans, together with a recently identified fourth hydrogenase (2), cytoplasmic membrane-bound NiFe hydrogenase (M. Rousset, unpublished data).

The role of D. fructosivorans periplasmic NiFe hydrogenase in metal reduction was proved by genetic and biochemical studies; this hydrogenase, but not purified cytochrome c3 alone, reduces Tc(VII) (6). Hydrogenase involvement in Pd(II) reduction is suggested by the Cu(II) sensitivity of the Pd(II) reductase of resting cells (11), but Cu(II) is not a specific hydrogenase inhibitor.

Resting cells of D. desulfuricans have been used previously to recover Pd(II) from industrial processing wastewaters and acidic leachates (25, 27). The biorecovery of palladium may be economically attractive since biorecovered Pd(0) is highly active catalytically (17). The objectives of this study were to establish the involvement of hydrogenase in Pd(II) reduction by using specific hydrogenase-negative mutant strains and to show the ability of hydrogenase to function under acidic conditions.

D. fructosivorans mutants were constructed using marker exchange mutagenesis (22). The D. fructosivorans wild-type strain and mutant strains with deletions of NiFe hydrogenase, Fe hydrogenase, and Fe and NiFe hydrogenases were grown anaerobically (in 2-liter cultures at 37°C for 48 h) (21). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g in a Beckman G2-21 M/E centrifuge for 20 min at 4°C), washed three times in 20 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-NaOH buffer, pH 7.0, and concentrated into 50 ml of the same buffer. Aliquots were used for the hydrogenase activity and Pd(II) reduction tests and for the preparation of periplasmically treated cells (see below).

The total hydrogenase activity (of resting cells) was estimated via the reduction of methyl viologen (8). The enzyme activities were consistent with the amounts of enzyme expressed according to the genotypes of the strains: 83.7% (0.169 ± 0.013 μmol of H2 consumed/min/109 cells [mean ± standard error of the mean]) and 13.5% (0.0273 ± 0.0026 μmol of H2 consumed/min/109 cells) of the wild-type level (0.202 ± 0.014 μmol of H2 consumed/min/109 cells) for the Fe hydrogenase- and NiFe hydrogenase-negative mutants, respectively. The hydrogenase activity of the double mutant (attributable to residual cytoplasmic membrane-bound hydrogenase) was 3.4% (0.00684 ± 4.46 × 10-4 μmol of H2 consumed/min/109 cells) of that of the wild type, in agreement with the observed residual activity in periplasmically treated cells.

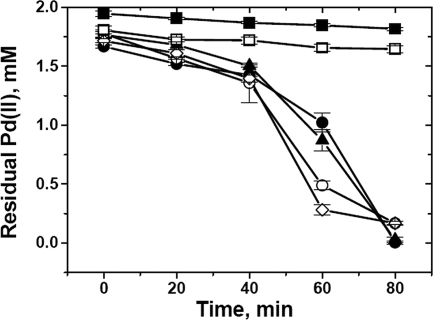

The reductions of Pd(II) by the parental and mutant strains were compared using sodium formate as the electron donor (Fig. 1). The amount of residual Pd(II) in the test solution was estimated using SnCl2-HCl (3); the estimate was cross-checked polarographically (26).

FIG. 1.

Reduction of Pd(II) by D. fructosivorans wild-type (•), Fe hydrogenase-negative mutant (▴), NiFe hydrogenase-negative mutant (○), and Fe hydrogenase- and NiFe hydrogenase-negative double-mutant (⋄) cells and in the control with no cells (▪) and the control with heat-killed cells (□). The ratio of the Pd(II) mass to the dry biomass was 1:3; the test solution was 2 mM Na2PdCl4, in 0.01 M HNO3. The difference between the dosed Pd(II) and that analyzed at the time of formate addition (at time zero) was attributable to biosorption by the biomass, and the quantity of biosorbed Pd (II) remained constant in the heat-killed cells. Ordinate data are means ± standard errors of the means. Where no error is shown, the error was within the dimensions encompassed by the symbol.

Figure 1 shows that all strains initially reduced Pd(II) at similar rates. After ∼40 min, the rates of reduction by the NiFe hydrogenase-negative mutant and the double mutant were higher. Only nucleation and the initiation of palladium crystal formation are dependent on hydrogenase activity; subsequent crystal growth is due to autocatalytic reduction (26).

The biorecovery of Pd(II) is optimal if an initial biosorption step (at pH 2 to 3 for 30 to 60 min) precedes hydrogenase-mediated metal reduction (26). The biosorption conditions were defined by de Vargas et al. (7), but hydrogenase stability at acidic pH has not been established. The measurement of hydrogen consumption (via methyl viologen reduction in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0 [8]) by purified D. fructosivorans periplasmic NiFe hydrogenase (preincubated in 20 mM glycine-HCl buffer, pH 2.2, for 1 h) showed that ∼32% of the initial hydrogenase activity was retained but that activity was lost after 2 h at acidic pH.

The hydrogenase was similarly active in a solution of 25 μM phenazine methosulfate (a high-potential indicator) in 20 mM glycine-HCl buffer, pH 2.2; the activity was 8.23 × 10−3 ± 0.21 × 10−3 A387 units/min/mg of protein. This result confirmed the tolerance of NiFe hydrogenase to acidic conditions. The hydrogenase enzymes may be more stable with respect to pH in their cellular locations. The residual activity (assuming that the effect of low pH on hydrogenase within the resting cells was similar to that in vitro) would be sufficient to achieve good Pd(II) removal, since enzyme activity is required only for initial Pd nanoparticle nucleation.

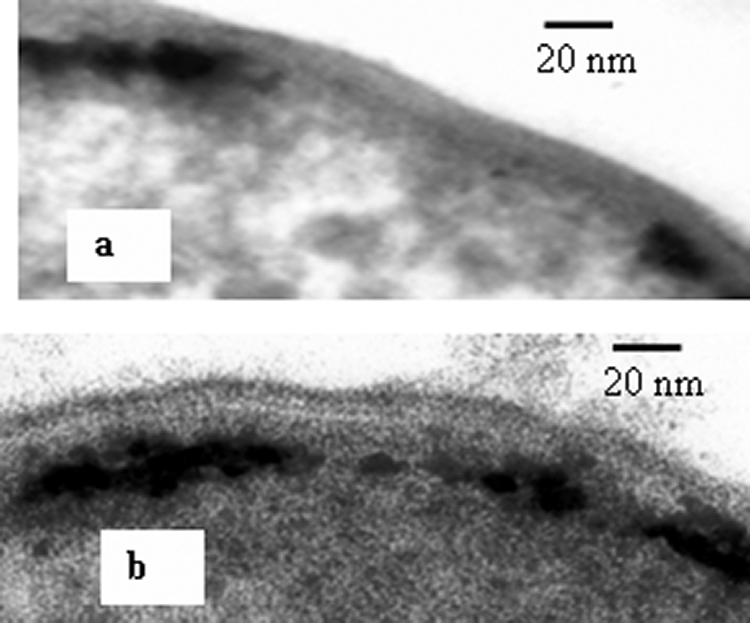

To obtain wild-type cells containing only membrane-bound hydrogenases, periplasmic proteins were extracted using a modification of a previously described method (9). Parent cells and double-mutant cells (used as a reference) were treated simultaneously to produce periplasmically treated cells. Treated-cell supernatants were concentrated from 200 to 5 ml by using a Millipore polyethersulfone ultrafiltration device (molecular weight cutoff, 30,000), and the activities of the extracted periplasmic hydrogenases were estimated. For the wild-type cells, the activity was 0.416 μmol of H2 consumed/min/mg of protein (methyl viologen test), whereas for the double mutant, it was zero, confirming that the extraction method did not affect the integrity of the cytoplasmic membrane. The activities of periplasmically treated wild-type and double-mutant cells were comparable to the activity of untreated double-mutant cells, confirming that membrane-bound hydrogenase remained active.

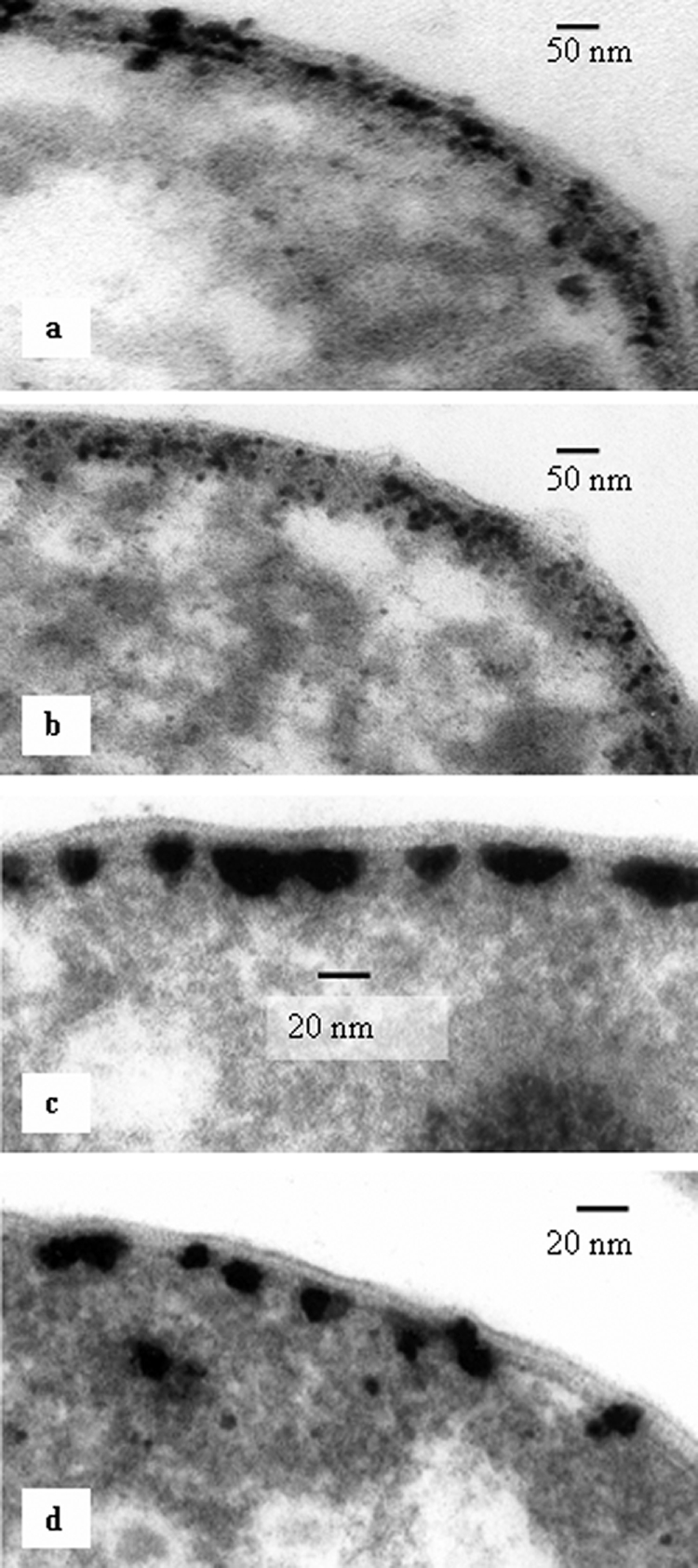

Palladized parent and mutant cells were obtained by reducing Pd(II) from 2 mM Na2PdCl4 at pH 2.3 under an atmosphere of H2. This procedure gave results identical to those obtained using formate. In order to observe the early stages of Pd cluster development, Pd(II) reduction was stopped after 5 min by outgassing H2 with N2. Pd-loaded bacteria were embedded in resin (25), and 90- to 100-nm-thick sections were viewed with a JEOL 120CX2 transmission electron microscope (TEM) with an energy-dispersive X-ray system for Pd detection (13).

Pd(0) was visible within the periplasmic spaces of the parent strain and the Fe hydrogenase mutants (Fig. 2a and b). Energy-dispersive X-ray analyses (data not shown) confirmed that the black particles associated with the cells were Pd (11). Pd clusters were distributed randomly throughout the whole width of the periplasmic space in the wild-type and Fe hydrogenase-negative cells (Fig. 2a and b), whereas in the NiFe hydrogenase-negative (Fig. 2c) and double-mutant (Fig. 2d) cells, they were localized on the cytoplasmic membrane. In both the double-mutant and wild-type periplasmically treated cells, Pd clusters were associated with the inner cytoplasmic membrane only (Fig. 3), similar to those in intact double-mutant cells (Fig. 2d). This localization of palladium was coincident with the localization of hydrogenase, suggesting that the enzyme serves as a nucleation site and assists initial Pd nanoparticle growth, probably by supplying the electrons for Pd(II) reduction.

FIG. 2.

TEM micrographs of initial stages of Pd cluster growth within the periplasm of a D. fructosivorans wild-type cell (a), an Fe hydrogenase-negative mutant cell (b), an NiFe hydrogenase-negative mutant cell (c), and an Fe hydrogenase- and NiFe hydrogenase-negative double-mutant cell (d).

FIG. 3.

TEM micrographs of palladized periplasmically treated wild-type (a) and double-mutant (b) D. fructosivorans cells.

In conclusion, we have shown that in the parent strain, Pd cluster growth can occur at both cytoplasmic membrane and periplasmic loci but that in the double mutant and the mutant lacking the major periplasmic hydrogenase, the nucleation sites are confined to the cytoplasmic membrane. The confinement of the nucleation sites to the cytoplasmic membrane has the effect of increasing the rate of Pd(II) reduction following the initial Pd cluster growth. Hence, in conjunction with the authors of other studies on Cr(VI) reduction using a bio-Pd catalyst from parent and double-mutant strains (M. Rousset, L. Casalot, P. de Philip, A. Bélaich, I. Mikheenko, and L. Macaskie, 24 August 2006, European patent application WO/2006/087334), we suggest that the catalytic activity of palladized cells can be enhanced by the correct choice of hydrogenase to mediate Pd(II) reduction.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of the European Union (BIO-CAT contract GRD1-2001-40424), the BBSRC (grant no. E13817), the EPSRC (grant no. GR/NO8445), and the Royal Society (industrial fellowship to L.E.M.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Casalot, L., E. C. Hatchikian, N. Forget, P. de Philip, Z. Dermoun, J.-P. Bélaich, and M. Rousset. 1998. Molecular study and partial characterization of iron-only hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. Anaerobe 4:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casalot, L., G. de Luca, Z. Dermoun, M. Rousset, and P. de Philip. 2002. Evidence for a fourth hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. J. Bacteriol. 184:853-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlot, G. 1978. Dosages absorptiométriques des éléments minéraux. Masson, Paris, France.

- 4.Clark, D. P. 1994. Chromate reductase activity of Enterobacter aerogenes is induced by nitrite. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 122:233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crameri, A., G. Dawes, E. Rodriguez, S. Silver, and W. P. C. Stemmer. 1997. Molecular evolution of an arsenate detoxification pathway by DNA shuffling. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:436-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Luca, G., P. de Philip, Z. Dermoun, M. Rousset, and A. Verméglio. 2001. Reduction of technetium by Desulfovibrio fructosovorans is enzymatically mediated by the nickel-iron hydrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4583-4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Vargas, I., L. E. Macaskie, and E. Guibal. 2004. Biosorption of palladium and platinum by sulfate-reducing bacteria. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 79:49-56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez, V. M., E. C. Hatchikian, and R. Cammack. 1985. Properties and reactivation of two different deactivated forms of Desulfovibrio gigas hydrogenase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 832:69-79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatchikian, E. C., A. Traore, V. M. Fernandez, and R. Cammack. 1990. Characterization of the nickel-iron periplasmic hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. Eur. J. Biochem. 187:635-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd, J. R., H.-F. Nolting, V. A. Sole, K. Bosecker, and L. E. Macaskie. 1998. Technetium reduction and precipitation by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Geomicrobiol. J. 15:43-56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd, J. R., P. Yong, and L. E. Macaskie. 1998. Enzymatic recovery of elemental palladium by using sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4608-4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lloyd, J. R., G. H. Thomas, J. A. Finlay, J. A. Cole, and L. E. Macaskie. 1999. Microbial reduction of technetium by Escherichia coli and Desulfovibrio desulfuricans: enhancement via the use of high-activity strains and effect of process parameters. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 66:122-130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd, J. R., J. Ridley, T. Khizniak, N. N. Lyalikova, and L. E. Macaskie. 1999. Reduction of technetium by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans: biocatalyst characterization and use in a flowthrough bioreactor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2691-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd, J. R., V. A. Sole, C. V. Van Praagh, and D. R. Lovley. 2000. Direct and Fe(II)-mediated reduction of technetium by Fe(III)-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3743-3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd, J. R., A. N. Mabbett, D. Williams, and L. E. Macaskie. 2001. Metal reduction by sulphate-reducing bacteria: physiological diversity and metal specificity. Hydrometallurgy 59:327-337. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovley, D. R. 1993. Dissimilatory metal reduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:263-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabbett, A. N., D. Sanyahumbi, P. Yong, and L. E. Macaskie. 2006. Biorecovered precious metals from industrial wastes: single-step conversion of a mixed metal liquid waste to a bioinorganic catalyst with environmental application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40:1015-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malki, S., I. Saimmaime, G. de Luca, M. Rousset, Z. Dermoun, and J.-P. Bélaich. 1995. Characterization of an operon encoding a NADP-reducing hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. J. Bacteriol. 177:2628-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michel, C. M., M. Brugna, C. Aubert, A. Bernadac, and M. Bruschi. 2001. Enzymatic reduction of chromate: comparative studies using sulfate-reducing bacteria. Key role of polyheme cytochromes c and hydrogenases. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 55:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oremland, R. S. 1994. Biogeochemical transformation of selenium in anoxic environments, p. 389-420. In W. T. Frankenberger, Jr., and S. Benson (ed.), Selenium in the environment. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, NY.

- 21.Rousset, M., L. Casalot, B. J. Rapp-Giles, Z. Dermoun, P. de Philip, J.-P. Bélaich, and J. D. Wall. 1998. New shuttle vectors for the introduction of cloned DNA in Desulfovibrio. Plasmid 39:114-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousset, M., Z. Dermoun, M. Chippaux, and J.-P. Bélaich. 1991. Marker exchange mutagenesis of the hydN genes in Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1735-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rousset, M., Z. Dermoun, E. C. Hatchikian, and J.-P. Bélaich. 1990. Cloning and sequencing of the locus encoding the large and small subunit genes of the periplasmic [NiFe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. Gene 94:95-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanke, L. J., R. D. Bryant, and E. J. Laishly. 1995. Hydrogenase I of Clostridium pasterianum functions as a novel selenite reductase. Anaerobe 1:661-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yong, P., J. P. Farr, I. R. Harris, and L. E. Macaskie. 2002. Palladium recovery by immobilized cells of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans using hydrogen as the electron donor in a novel electrobioreactor. Biotechnol. Lett. 4:205-212. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yong, P., N. A. Rowson, J. P. Farr, I. R. Harris, and L. E. Macaskie. 2002. Bioaccumulation of palladium by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 77:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yong, P., N. A. Rowson, J. P. Farr, I. R. Harris, and L. E. Macaskie. 2003. Palladium reduction in a bioelectrochemical reactor: a novel method for the recovery of precious metals from waste/process solution. Environ. Technol. 24:289-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]