Abstract

φC31 integrase is a serine recombinase containing an N-terminal domain (NTD) that provides catalytic activity and a large C-terminal domain that controls which pair of DNA substrates is able to synapse. We show here that substitutions in amino acid V129 in the NTD can lead to defects in synapsis and DNA cleavage, indicating that the NTD also has an important role in synapsis.

The integrase (Int) of the Streptomyces phage, φC31, is a member of the large serine recombinases, a family of proteins that includes phage Ints and transposases (11). φC31 Int has two domains, the N-terminal domain (NTD), which provides the catalytic activity, and the C-terminal domain (CTD), required for the control of integration versus excision (9, 13). All of the phage-encoded large serine recombinases that have been studied in detail are unidirectional in the absence of accessory factors (2, 7, 13). The DNA substrates (attB, attP, attL, and attR) for the phage-encoded serine Ints are small (<50 bp) compared to those used by other directional recombinases (2, 4, 7, 14). For integration, Int dimers bind to attP and attB, and dimer-dimer interactions are thought to bring the substrates together to form a tetrameric synaptic complex (5, 6, 14). Synapsis is prevented when Int is bound to attL and attR, and this underpins Int unidirectionality in the absence of accessory factors (12, 14). Mutations in the CTD cause hyperactivity, i.e., Int is able to mediate both attB × attP and attL × attR synapsis and recombination. Since these mutations lie in a putative coiled-coil motif, it is possible that the CTD has a direct role in protein-protein interactions in synapsis. In the resolvase/invertase group of serine recombinases, genetic, biochemical, and structural information has shown that synapsis occurs via the NTDs. There is considerable sequence divergence between the NTDs of the large serine recombinases and those of the resolvase/invertases; for instance, the NTDs of γδ and φC31 Int are only 20% identical, as shown by a CLUSTAL W alignment (Fig. 1). Since formation of the synapse is central to understanding how Int controls directionality, we sought to determine whether the φC31 NTD is involved in synapsis of Int bound to attP and attB.

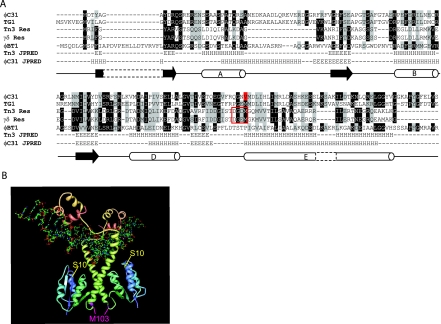

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment and predicted structural similarities between the NTDs of several serine recombinases. (A) CLUSTAL W alignment of γδ resolvase, Tn3 resolvase, φC31 Int, and the Ints from two φC31-related Streptomyces phages, TG1 and φBT1. Gray background shading represents conserved amino acids, and black shading indicates that >50% of the sequences have an identical residue at that position. The position of V129 in φC31 Int is indicated by a red highlight, and amino acids 100 to 103 in the resolvases are boxed. JPRED secondary structure predictions are displayed below the alignment for Tn3 resolvase and for φC31 Int with a diagram depiction of the γδ secondary structure below (3) (H); cylinders represent α-helix (E), and black arrows represent the β-sheet. (B) Structure of γδ dimer bound to DNA (1GDT; 15). The position of γδ M103, which aligns with φC31 IntV129, is indicated in pink. The catalytic serine, S10, is highlighted in yellow. The image was created with PDB Protein Workshop.

Despite the sequence divergence, the output from a structure prediction program JPRED (3) for φC31 Int NTD resembled the structure of the NTD of γδ and Tn3 resolvase, with the conservation of important structural elements. In the resolvases, substitutions at residues 100 to 103 can lead to activated resolvases, which no longer require accessory sites for recombination (1). Whereas wild-type (wt) resolvase is dimeric in solution, activated mutants of resolvase are tetrameric through dimer-dimer interactions that generate the synaptic interface (10). The tertiary structures of wt resolvase dimers and the tetrameric synaptic intermediate are very different, particularly in the positioning of the long E helix (8, 15). Since residues 100 to 103 are at the heart of the synaptic interface and are located where a flexible linker joins the long E helix, substitutions here are thought to facilitate the conformational changes associated with the dimer-to-tetramer transition (8). A mutant φC31 Int, IntV129A, was isolated previously from a library of defective Int mutants (9). Since IntV129A aligned with M103 from resolvase, we were interested to discover the basis for its poor activity. IntV129A was overexpressed, purified, and assayed for in vitro recombination activity. IntV129A was very defective in attP × attB recombination and had no detectable attL × attR activity (Fig. 2 and data not shown). To assay synapsis, a doubly substituted Int was generated, IntS12A,V129A. The S12A mutation inactivates the serine nucleophile and permits accumulation of synaptic complexes, which can be detected in vitro using DNA supershifts in nondenaturing gels (12). The amount of free attB was reduced at the same rate in reactions with IntS12A and IntS12A,V129A, indicating that binding to attB was not affected by the V129A substitution (Fig. 3A). IntS12A, however, accumulated synaptic complexes at a faster rate and to a greater level (sixfold more synapse present after 60 min) than IntS12A,V129A (Fig. 3A).

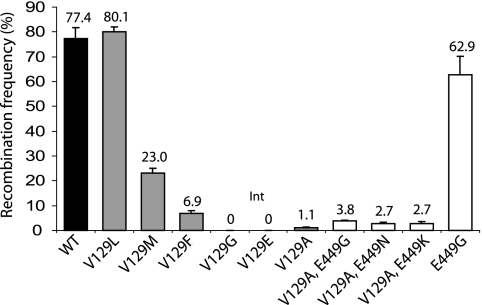

FIG. 2.

In vitro activities of purified Ints containing different substitutions at V129. Quantitative assay of recombination activity in vitro of wt Int (▪) versus Int mutants with single substitutions (□) and double substitutions (□). Ints were purified and assayed as described previously (9, 12). Ints (733 nM) were incubated (2 h, 30°C in R buffer) with the reporter plasmid, pRT508 (0.15 nM) encoding attP and attB flanking lacZ. Deletion of the lacZ marker in pRT508 by attP × attB recombination was assayed by introduction of the whole reaction mixture into DH5α and scoring the fraction of white colonies after selection for transformants on plates containing carbenicillin, X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). The data are the averages and standard errors for two replicates.

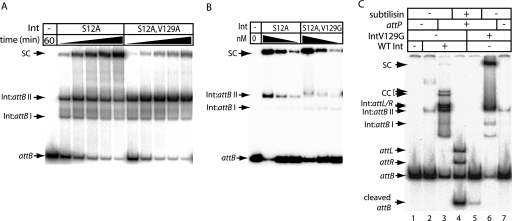

FIG. 3.

Effects of the V129 substitutions on DNA synapsis and cleavage. (A) The catalytically inactive mutants IntS12A and IntS12A,V129A were used to assay the formation of synaptic complexes. Reactions contained radiolabeled attB (1.5 nM), unlabeled attP (14 nM), and Int (733 nM) in binding buffer (12) and were incubated (30°C) for 10, 20, 40, 60, or 120 min. Reactions were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5% polyacrylamide, 1× Tris-borate-EDTA). The complexes observed were as described previously (12) and are Int bound to attB (Int:attB complexes I and II, which are most likely Int monomers and dimers, respectively) or synaptic complexes (SC). (B) A V129G mutation did not adversely affect the ability of IntS12A to synapse. Three concentrations (92, 46, or 23 nM) of IntS12A or IntS12A,V129G were incubated (30°C, 2 h) with radiolabeled attB and unlabeled attP as described in panel A. (C) The mutation V129G inhibits DNA cleavage. wt Int (733 nM; lanes 5 to 7) or IntV129G (733 nM; lanes 2 to 4) was incubated with radiolabeled attB with or without unlabeled attP as described in panel A. attB-bound complexes are indicated (Int:attB I and II). Recombination intermediates were characterized previously (12) and are indicated as SC (for synaptic complexes) and CC (for covalent complexes). Free recombination products, attL and attR, or products bound to Int, Int:attL, and Int:attR are also indicated. Subtilisin was added to lanes 4 and 5 to release the DNA from bound Int. Free attB is shown in lane 1.

Since IntV129A is a conservative mutation, site-directed mutagenesis was used to investigate how other amino acid substitutions at V129 influenced Int recombination. Five substitutions were introduced at position V129 (V129G, V129L, V129M, V129F, and V129E). The mutant proteins were purified and tested for in vitro recombination activity with attB and attP (Fig. 2). Int V129G and Int V129E were inactive in vitro. Gel filtration analysis of the purified mutant Int showed that all V129 mutants were dimeric in solution, indicating that monomer-monomer interactions were not affected by the substitutions at V129 (data not shown).

Since formation of the synaptic complex was inhibited by V129A (Fig. 3A), synapsis by IntV129G, IntV129L, IntV129M, and IntV129F was assayed. The S12A mutation was introduced into each int allele and, with the exception of IntS12A,V129E, the proteins purified. Like IntS12A,V129A, IntS12A,V129F was defective in synapsis. IntS12A,V129L, IntS12A,V129M, and IntS12A,V129G were as efficient as IntS12A in the synapsis of attB and attP (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Since IntV129G was completely defective in the attP × attB recombination but able to synapse as well as wt Int, we tested whether V129G might be defective in the step that follows synapsis, i.e., DNA cleavage.

Concomitant with DNA cleavage by Int a phospho-serine bond is made, most likely between the 5′ end of the DNA and amino acid S12. This cleaved intermediate can be readily detected when Int is provided with linear substrates (one of which is radiolabeled) and, after incubation is treated with a protease (12). IntV129G showed a noticeable reduction in the amount of cleaved substrate compared to wt Int and a corresponding increase in the amount of synaptic complex (Fig. 3C). Thus, recombination-defective mutations at V129 can be affected in synapsis and activation of DNA cleavage.

In the crystal structures of γδ resolvase, the flexing of the linker region adjacent to M103 is an obvious feature of the transition from the dimeric to the tetrameric structures, a conformational change that is centered on the movement and packing of four E-helices (8). It seems likely that V129 has a similar function in Int as M103 has in the resolvases, playing a part in both synapsis and in the conformation changes that are thought to occur postsynapsis to activate DNA cleavage. It is noteworthy that cleavage defects of this kind have yet to be reported for any mutations within the same region of the resolvases.

Mutations in the CTD of Int partly rescue the unstable synapsis of V129A.

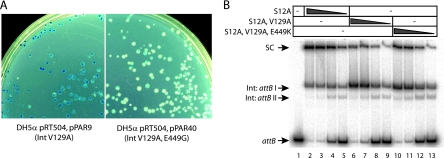

Previous work has demonstrated that a single mutation within the Int CTD at position E449 enable the recombinase to undertake a variety of novel recombination reactions (9). The basis for this extended recombinational repertoire is thought to be the ability of the mutant Int to stabilize a synapse between att sites that would not normally form a synaptic complex (9). Since V129 appeared to be involved in synapsis, the question arose as to whether this residue interacts independently of, or in concert with, the Int CTD during Int synapsis and recombination. To test this, plasmids encoding IntV129A and IntV129G were used as substrates for site-directed mutagenesis to introduce mutations at E449. The double mutants were tested in an in vivo recombination assay in which deletion of lacZ by attP × attB recombination resulted in a white colony color on selective media (9). IntV129A,E449G showed a restoration of attP × attB recombination in vivo, indicated by extensive white sectoring in the transformants compared to largely blue colonies in transformants expressing IntV129A (Fig. 4A). Plasmids encoding double mutants that combined IntV129A with E449K, E449H, E449F, E449N, or E449R all gave similar sectored white and blue colonies (data not shown). In contrast, plasmids encoding either IntV129G,E449K or IntV129G,E449N gave only blue colonies, indistinguishable from those obtained in the presence of the single mutant IntV129G (data not shown). IntV129A,E449G, IntV129A,E449K, and IntV129A,E449N were purified and used in in vitro recombination assays and compared to wt Int and IntV129A. A small but consistent increase in the frequency of attP × attB recombination was observed when V129A was combined with E449G, E449N, or E449K (Fig. 2). The modest rescue of activity was investigated further through the construction of an S12A derivative of IntV129A,E449K in order to test the ability of this triple mutant to synapse attB and attP. Under the same conditions IntS12A,V129A,E449K was able to trap, reproducibly, twice the amount of attB probe into synaptic complexes compared to the double mutant IntS12A,V129A (Fig. 4B). The substitution E449K was, therefore, partially able to rescue the synapse defect caused by the mutation V129A, which may have resulted in the small increase in in vivo attP × attB recombination activity (Fig. 2). It is not known to what extent IntV129A could be affected in DNA cleavage in addition to the synapse defect. Since E449K appeared to be unable to rescue the DNA cleavage defect in IntV129G, introduction of the E449K mutation into IntV129A would not be expected to enhance DNA cleavage, and this could help to explain the low recombination activity in the IntV129A mutants, particularly IntV129A,E449K. None of the double mutants containing substitutions in both V129 and E449 were able to recombine attL × attR (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Partial rescue of recombination activity and synapse formation in V129A by hyperactive mutations at E449. (A) In vivo recombination by IntV129A versus IntV129A,E449G. Almost every colony containing pPAR40 (encoding IntV129A,E449G) is mainly white, with some blue sectors, indicating loss of the lacZ gene in pRT504 after attP × attB recombination (9). This is compared to largely blue colonies obtained when pPAR9 (encoding IntV129A) is present with pRT504. (B) Synapsis by IntS12A (lanes 2 to 5), IntS12A,V129A (lanes 6 to 9), and IntS12A,V129A,E449K (lanes 10 to 13). Radiolabeled attB was incubated with unlabeled attP and various concentrations of Int—246 nM (lanes 2, 6, and 10), 123 nM (lanes 3, 7, and 11), 61 nM (lanes 4, 8, and 12), or 31 nM (lanes 5, 9, and 13)—as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Quantitation of the signal intensities in the synaptic complexes formed with 246 nM Int revealed that over two independent experiments the mean percentage of counts in the IntS12A,V129A,E449K synapse was 39.6% ± 0.03% (standard error) compared to 19.7% ± 0.23% with IntS12A,V129A.

The data presented here indicate that the NTD of the large serine recombinase φC31 Int has a role in synapsis and activation of recombination. We propose that, like resolvase, Int has a flexible region around V129 that is crucial for the communication of conformation changes and activation of catalysis (8). Due to the fact that recombination is regulated by the formation of a stable synapse, we and others have proposed that Int bound to attP and attB adopts specific conformers that allow synapsis (5, 12, 14). It seems likely that protein conformations in the CTD, adopted through binding to different att sites, influence the stability of the synaptic interface in the N-terminal domain and the activation of DNA cleavage.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council of the United Kingdom (grant reference BB/D007836/1) and by a University of Aberdeen studentship to P.A.R.

We are grateful to The Medical Illustration Unit, University of Aberdeen, for photography.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, P. H., D. G. Blake, N. D. F. Grindley, M. R. Boocock, and W. M. Stark. 1999. Mutants of Tn3 resolvase which do not require accessory binding sites for recombination activity. EMBO J. 181407-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibb, L. A., M. I. Hancox, and G. F. Hatfull. 2005. Integration and excision by the large serine recombinase φRv1 integrase. Mol. Microbiol. 551896-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuff, J. A., and G. J. Barton. 2000. Application of multiple sequence alignment profiles to improve protein secondary structure prediction. Proteins 40502-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh, P., A. I. Kim, and G. F. Hatfull. 2003. The orientation of mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integration is solely dependent on the central dinucleotide of attP and attB. Mol. Cell 121101-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh, P., N. R. Pannunzio, and G. F. Hatfull. 2005. Synapsis in phage Bxb1 integration: selection mechanism for the correct pair of recombination sites. J. Mol. Biol. 349331-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta, M., R. Till, and M. C. M. Smith. 2007. Sequences in attB that affect the ability of φC31 integrase to synapse and to activate DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 353407-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, A. I., P. Ghosh, M. A. Aaron, L. A. Bibb, S. Jain, and G. F. Hatfull. 2003. Mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integrates into the Mycobacterium smegmatis groEL1 gene. Mol. Microbiol. 50463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, W., S. Kamtekar, Y. Xiong, G. J. Sarkis, N. D. F. Grindley, and T. A. Steitz. 2005. Structure of a synaptic gamma-delta resolvase tetramer covalently linked to two cleaved DNAs. Science 3091210-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowley, P. A., M. C. A. Smith, E. Younger, and M. C. M. Smith. 2008. A motif in the C-terminal domain of φC31 integrase controls the directionality of recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 363879-3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkis, G. J., L. L. Murley, A. E. Leschziner, M. R. Boocock, W. M. Stark, and N. D. F. Grindley. 2001. A model for the gamma delta resolvase synaptic complex. Mol. Cell 8623-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith, M. C. M., and H. M. Thorpe. 2002. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol. Microbiol. 44299-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith, M. C. A., R. Till, K. Brady, P. Soultanas, H. Thorpe, and M. C. M. Smith. 2004. Synapsis and DNA cleavage in φC31 integrase-mediated site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 322607-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorpe, H. M., and M. C. M. Smith. 1998. In vitro site-specific integration of bacteriophage DNA catalyzed by a recombinase of the resolvase/invertase family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 955505-5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorpe, H. M., S. E. Wilson, and M. C. M. Smith. 2000. Control of directionality in the site-specific recombination system of the Streptomyces phage φC31. Mol. Microbiol. 38232-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, W., and T. A. Steitz. 1995. Crystal structure of the site-specific recombinase gamma-delta resolvase complexed with a 34-bp cleavage site. Cell 82193-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]