Abstract

Rationale: An association between neurocognitive deficits and pediatric sleep-disordered breathing has been suggested; however, weak correlations between disease severity and functional outcomes underscore the lack of knowledge regarding factors modulating cognitive morbidity of sleep-disordered breathing.

Objectives: To identify the parameters affected by sleep-disordered breathing that modulate cerebral oxygenation, an important determinant of cognition. A further objective was to use these parameters with demographic data to develop a predictive statistical model of pediatric cerebral oxygenation.

Methods: Ninety-two children (14 control subjects, 32 with primary snoring, and 46 with obstructive sleep apnea) underwent polysomnography with continuous monitoring of cerebral oxygenation and blood pressure. Analysis of covariance was used to relate the blood pressure, sleep diagnostic parameters, and demographic characteristics to regional cerebral oxygenation.

Measurements and Main Results: To account for anatomic variability, an index of cerebral oxygenation during sleep was derived by referencing the measurement obtained during sleep to that obtained during wakefulness. In a repeated measures model predicting the index of cerebral oxygenation, mean arterial pressure, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, female sex, age, and oxygen saturation had a positive effect on cerebral oxygenation levels, whereas arousal index and non-REM (NREM) sleep had a negative effect.

Conclusions: Increasing mean arterial pressure, age, oxygen saturation, and REM sleep augment cerebral oxygenation, while sleep-disordered breathing, male sex, arousal index, and NREM sleep diminish it. The proposed model may explain the sources of variability in cognitive function of children with sleep-disordered breathing.

Keywords: children, sleep-disordered breathing, cerebral oxygenation

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

An association between neurocognitive deficits and pediatric sleep-disordered breathing has been suggested; however, weak correlations between disease severity and functional outcomes underscore the lack of knowledge regarding factors modulating cognitive morbidity of sleep-disordered breathing.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Increasing mean arterial pressure, age, oxygen saturation, and REM sleep augment cerebral oxygenation, while sleep-disordered breathing, male sex, arousal index, and NREM sleep diminish it. The proposed model may explain the sources of variability in cognitive function of children with sleep-disordered breathing.

The pediatric syndrome of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), which encompasses both primary snoring and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), affects more than 12% of children (1, 2). Whereas children with primary snoring have only a limited number of obstructive airway events during sleep, those with OSA characteristically experience varying, but more frequent episodes of airway obstruction. Although cognitive deficits have been described in children with SDB, evidence of a causal relationship between SDB and these deficits has not been firmly established (3–9). The absence of a dose-dependent association of cognitive deficits with increasing severity of OSA, coupled with findings of cognitive deficits in children with primary snoring, has challenged the notion of an adverse effect of SDB on cognition (10, 11). To the contrary, however, SDB may indeed be causally related to the development of cognitive deficits, with the biological factors that modify its effect on cognition not yet identified.

There is strong evidence that a sustained decrease of regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in adults is related to postoperative decline in cognitive function (12, 13). Studies have also shown that in adults with OSA, obstructive airway events are associated with transient decreases in rSO2 (14). Other research has demonstrated an association between OSA and long-term cerebrovascular disease in adults (15).

In view of this combined body of evidence and because of the well-described association between pediatric SDB and cognitive disorders, we hypothesized that pediatric SDB is associated with a dose-dependent, steady-state decrease in rSO2 during sleep. We tested this hypothesis first by comparing the steady-state difference in rSO2 between children with SDB and healthy control subjects, and then using these results to develop a predictive, dose-dependent model relating rSO2 during sleep to its respiratory, cardiovascular, and sleep-related determinants.

METHODS

Subjects

Children ranging in age from 7 to 13 years being treated for nightly snoring and hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids were recruited for the study. All of these children underwent overnight polysomnography (PSG) to establish a baseline assessment of breathing during sleep. Children were divided into two subgroups: (1) those with primary snoring (i.e., a PSG showing an apnea–hypopnea index [AHI] of ≤ 1), and (2) those with OSA (i.e., an AHI > 1). Other inclusion criteria were the absence of chronic medical conditions and genetic syndromes. Age- and sex-matched healthy children recruited from our institution and local pediatric practices constituted a control group. Inclusion criteria for this group were the absence of a history of obstructive breathing during sleep and the absence of SDB or alveolar hypoventilation on PSG. Children receiving medications for chronic conditions were excluded if they were unable to discontinue these medications during the course of our study. This study was approved by the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center institutional review board. Parents signed an informed consent before enrollment in the study. Children 7 years of age or older signed an assent form.

Study Design

A medical history was taken, and a physical examination was performed on all children. Next, all underwent standard overnight PSG with simultaneous rSO2 monitoring (Near Infrared Spectroscopy [NIRS] INVOS 5100 cerebral oximeter; Somanetics, Troy, MI) and beat-to-beat blood pressure measurements (Portapres; TNO-TPD Biomedical Instrumentation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). PSG studies were performed according to the American Thoracic Society standards (16) using a computerized system (Grass, Telefactor; Astro Inc., West Warwick, RI). Each signal was sampled and stored at 500 Hz.

NIRS

NIRS, a technique for assessing rSO2, shows excellent correlation with jugular venous oxygenation (17). Further, the value of monitoring rSO2 in examining cerebral physiologic functions in normal states and in a number of cardiac and neurologic disorders has been demonstrated in several studies in infants, children, and adults (18–23). Collectively, these studies validate NIRS as a noninvasive method of monitoring rSO2 in children, and emphasize its clinical applicability across a wide range of ages and disorders.

NIRS measures light absorption by hemoglobin, both in arterioles and capillaries and in the venous system. Because most blood (volumetrically) is held in the venous system, the absorbed light measured is dominated by venous saturation, and thus reflects the balance between oxygen supply and demand in the brain. Hence, NIRS provides information describing tissue metabolism and oxygenation.

NIRS of cerebral blood flow depends on detection of energy emission through the skull and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Since skull thickness and amount of CSF vary with individual anatomy, absolute measures of rSO2 should be normalized. We normalized this measurement using child-specific mean values during wakefulness as the baseline to calculate normalized rSO2 (ΔrSO2) values during sleep. As such:  Typically, rSO2 is lower during sleep than during wakefulness.

Typically, rSO2 is lower during sleep than during wakefulness.

Data Processing

PSGs were scored for sleep stage and arousals according to accepted standards (24). An obstructive airway event (apnea) was defined as the presence of respiratory effort in the absence or decrease of airflow by more than 80% of the preceding breath and lasting for at least two respiratory cycles. Partial obstructive airway events (hypopnea) were classified as the presence of respiratory effort with a decrease of airflow between 50 and 80% of the preceding respiratory cycle. Central apneas were classified as the cessation of respiratory effort and airflow for at least two respiratory cycles. The AHI was defined as the number of obstructive airway events (apneas, hypopneas, and mixed central and obstructive apneas) per hour of total sleep time. The respiratory arousal index was defined as the total number of respiratory arousals per hour of sleep. All scoring was performed by a single sleep technician and reviewed by the same pediatric sleep physician. After scoring, all signals were indexed according to sleep stage and respiratory event occurrence.

It has been shown in adults that during obstructive events there are parallel changes in systemic oxygen saturation and rSO2 (14). We anticipated similar changes in children, as systemic oxygen saturation is an important predictor of rSO2 (25). Our intent in this study was to examine rSO2 for the whole duration of sleep without the confounding effect of obstructive events. Therefore, data recorded during respiratory events were not used for subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analysis

For each subject, 5-minute signal means were calculated. The means were used in a repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model to determine significant predictors of ΔrSO2 and to measure difference between groups (control versus primary snoring and control versus OSA). Diagnostic statistics (predicted residual sums of squares [PRESS]) were calculated to measure any undue individual influences on group mean estimates. Initial covariates in the model included group, age, race, sex, body mass index Z-score (BMIZ), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), end-tidal CO2, oxygen saturation (SaO2), and arousal index. Using fit statistics and residual analysis, a repeated measures model that provided the best fit for each group was identified using a separate auto-regressive moving average covariance structure.

To include stage as a time-varying covariate, 1-minute means of ΔrSO2 were calculated for each subject. Sleep stage was noted for each 1-minute mean. Where a mean included more than one stage, that mean was not included in the analysis. Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and MAP were also modeled using 1-minute means in a repeated measures ANCOVA model. Comparisons of least-squares means between control and primary snoring and control and OSA were made using Dunnett's multiple comparison adjustment. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Subjects

Ninety-three children were enrolled in the study. Data from one child in the primary snoring group were identified by the PRESS statistic calculations as exerting an undue influence on the group mean and were eliminated from further analysis (male, age 9, African American, BMI = 22.7, overnight individual mean ΔrSO2 = −15). Thus, data from 92 children with a mean age of 10.0 ± 1.96 years were included in the analyses. Based on the screening history and PSG results, the study population was subdivided into 32 children with primary snoring, 46 with OSA, and 14 control subjects. All three groups were matched for age, sex, and race. Compared with healthy control subjects, children with primary snoring differed in their BMI, while children with OSA differed in BMI, AHI, and arousal index. The average sleep onset time during which awake baseline rSO2 was calculated was 50 min ± 31 minutes. The demographic and PSG data for these groups are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

MEANS, STANDARD DEVIATIONS, AND FREQUENCIES FOR DEMOGRAPHIC AND POLYSOMNOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS BY GROUP (CONTROL, PRIMARY SNORING, AND OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA)

| Controls | Primary Snoring | OSA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n = 14) | (n = 32) | (n = 46) | P Value |

| Male | 57% | 44% | 57% | 0.4973 |

| White | 57% | 56% | 57% | 0.9984 |

| Age | 10.2 (1.9) | 10 (1.8) | 10 (2) | 0.8915 |

| BMI | 18 (2.7) | 22.3 (6)* | 22.3 (5)† | 0.0261 |

| BMIZ | 0.27 (0.9) | 1.2 (1)* | 1.2 (1)† | 0.0108 |

| AHI | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 10 (17)‡ | <0.0001 |

| ETco2 (Sleep) | 43 (2) | 42 (4) | 40 (5)‡ | 0.0394 |

| SaO2 (Sleep) | 97 (1) | 97 (1) | 96 (2) | 0.1737 |

| % stage 1 | 4 (2) | 4 (4) | 4 (2) | 0.1916 |

| % stage 2 | 47 (10) | 48 (8) | 51 (8) | 0.2282 |

| % stage 3 | 3 (07) | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.9139 |

| % stage 4 | 28 (8) | 28 (6) | 26 (7) | 0.3052 |

| % REM | 18 (4) | 16 (5) | 16 (5) | 0.4354 |

| Arousal index | 8 (2) | 8 (3) | 14 (12)† | 0.0003 |

| Total sleep time | 394 (50) | 386 (54) | 401 (41) | 0.6207 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea hypopnea index; BMI = body mass index; BMIZ = body mass index (Z score); ETco2 = end-tidal CO2; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; REM = rapid eye movement.

Chi-square tests for association used for sex and race. All other differences tested with Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test (P values reported for overall test).

P = 0.001, control versus OSA, or control versus primary snoring.

P < 0.01, control versus OSA, or control versus primary snoring.

P < 0.0001, control versus OSA, or control versus primary snoring.

Determinants of Normalized ΔrSO2

Modeling ΔrSO2 without sleep stages.

A group comparison of ΔrSO2 independent of stages of sleep was performed. In a repeated measures analysis that included group, age, race, sex, BMIZ, MAP, end-tidal CO2, SaO2, and arousal index as independent variables, the mean ΔrSO2 significantly differed between children with primary snoring and control subjects (P = 0.04; using the Dunnett adjustment for multiple comparisons, P = 0.07). There was no difference in ΔrSO2 between children with OSA and control subjects. The significant predictors (α = parameter estimate for change in intercept; β = parameter estimate for change in slope) of ΔrSO2 included female sex (β = 0.8, P = 0.02), age (β = 0.2, P = 0.005), MAP (β = 0.06, P < 0.0001), SaO2 (β = 0.07, P = 0.02), and arousal index (β = - 0.04, P = 0.02).

Modeling ΔrSO2 with sleep stages.

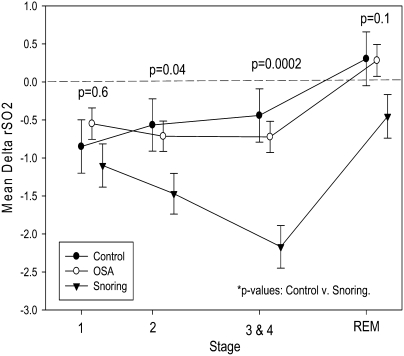

ΔrSO2 characteristically increased from non–rapid eye movement (NREM) to REM sleep for each of the three groups (Figure 1, Table 2). During REM sleep, the rSO2 levels in children with primary snoring did not reach levels measured during wakefulness. By comparison, the level of rSO2 exceeded the mean rSO2 during wakefulness (Figure 1, Table 2) in control subjects and in children with OSA.

Figure 1.

Normalized regional cerebral oxygenation (ΔrSO2) means for sleep stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 and rapid eye movement for control subjects, children with primary snoring, and children with OSA. ΔrSO2 = difference in cerebral oxygenation between sleep and wake periods; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

TABLE 2.

DIFFERENCES IN LEAST SQUARES MEANS FOR ΔrSO2 BETWEEN STAGES 1, 2, 3, AND 4 AND REM SLEEP, WITHIN GROUP (CONTROL, PRIMARY SNORING, AND OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA)

| Controls

|

Primary Snoring

|

OSA

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | dLSM ± SE | P Value | dLSM ± SE | P Value | dLSM ± SE | P Value |

| 1 versus 2 | −0.28 ± 0.094 | 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.09 |

| 1 versus 3-4 | −0.41 ± 0.13 | 0.01 | 1.07 ± 0.17 | <0.0001 | 0.17 ± 0.10 | 0.44 |

| 1 versus REM | −1.15 ± 0.13 | <0.0001 | −0.65 ± 0.16 | 0.0005 | −0.83 ± 0.10 | <0.0001 |

| 2 versus 3 and 4 | −0.13 ± 0.10 | 1.0 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | <0.0001 | 0.01 ± 0.07 | 1.0 |

| 2 versus REM | −0.87 ± 0.11 | <0.0001 | −1.02 ± 0.13 | <0.0001 | −1.00 ± 0.08 | <0.0001 |

| 3 and 4 versus REM | −0.75 ± 0.14 | <0.0001 | −1.72 ± 0.18 | <0.0001 | −1.01 ± 0.10 | <0.0001 |

Definition of abbreviations: ΔrSO2 = change in regional cerebral oxygen saturation; dLSM = Difference ± SE of ΔrSO2 least squares means; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

P values reflect a Bonferroni multiple-comparison adjustment within group.

As shown in Figure 1, the association between specific sleep stages and ΔrSO2 differed in control subjects as compared both to children with primary snoring and those with OSA. In control subjects, ΔrSO2 levels during stage 1 sleep were significantly lower than those during stage 2. There was an opposite association between ΔrSO2 levels measured in stage 1 and 2 sleep in children with primary snoring and those with OSA. In children with primary snoring, ΔrSO2 was significantly lower during stages 3 and 4 as compared with stage 2 sleep. In contrast, there was no statistical difference in the ΔrSO2 levels measured during stage 2 sleep and stages 3 and 4 sleep in control subjects and in children with OSA (Figure 1, Table 2).

In a repeated measures model that included group, stage, group by stage interaction, age, sex, MAP, SaO2, and arousal index as independent variables, a significant difference was measured in ΔrSO2 between children with primary snoring and control subjects (P = 0.037; using the Dunnett adjustment for multiple comparisons, P = 0.06). After adjustment for multiple comparisons, the differences were significant in stage 2 sleep (P = 0.04) and stages 3 and 4 combined (P = 0.0002). MAP showed the strongest association with ΔrSO2 (Table 3). Whereas there was a positive association between ΔrSO2 and MAP, age, female sex, and REM sleep, a negative association emerged between ΔrSO2 and NREM sleep and the arousal index. Initial analyses demonstrated that race, BMIZ, and end-tidal CO2 were not significant predictors of ΔrSO2, and were excluded from the final model. There was no significant difference in mean ΔrSO2 between children with OSA and control subjects.

TABLE 3.

PREDICTORS OF ΔrSO2 DERIVED FROM REPEATED MEASURES MODEL USING 1-MIN MEANS WHERE STAGE WAS INCLUDED AS TIME-VARYING COVARIATE

| Variable | Estimate | SE | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||

| Control | −5.0880 | 1.4343 | 0.0004 |

| Primary snoring | −5.8452 | 1.4190 | <0.0001 |

| OSA | −5.1093 | 1.4047 | 0.0003 |

| Stage 1 | −0.6461 | 0.1646 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | −1.0179 | 0.1320 | <0.0001 |

| 3 and 4 | −1.7159 | 0.1768 | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 0.8208 | 0.2902 | 0.005 |

| Age | 0.2502 | 0.07411 | 0.0008 |

| MAP | 0.05297 | 0.001701 | <0.0001 |

| SaO2 | −0.00427 | 0.01188 | 0.7 |

| Arousal index | −0.05022 | 0.01673 | 0.003 |

Definition of abbreviations: ΔrSO2 = change in regional cerebral oxygen saturation; MAP = mean arterial pressure; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Parameter estimates (SE = standard error) are given.

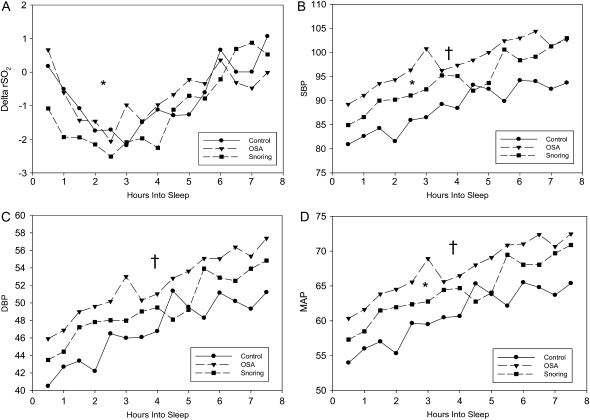

SBP, DBP, and MAP during sleep.

Blood pressure was significantly higher in children with SDB (Figures 2B, 2C, and 2D). Least squares means analysis of these data show that compared with control subjects, children with primary snoring had higher SBP (89 ± 1 mm Hg versus 95 ± 1 mm Hg; P = 0.0006) and MAP (62 ± 0.7 mm Hg versus 65 ± 0.7 mm Hg; P = 0.002) than control subjects. Children with OSA differed from control subjects in SBP (99 ± 0.9 mm Hg; P < 0.0001), in DBP (52 ± 0.7 mm Hg; P < 0.0001), and in MAP (68 ± 0.8 mm Hg; P < 0.0001). These differences were measured after controlling for age, sex, race, and BMIZ score (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Thirty-minute means for (A) ΔrSO2, (B) systolic blood pressure, (C) diastolic blood pressure, and (D) mean arterial blood pressure by group. †P < 0.05 between control subjects and subjects with OSA; *P < 0.05 between control subjects and primary snoring.

TABLE 4.

PREDICTORS OF SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE, DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE, AND MEAN ARTERIAL BLOOD PRESSURE DERIVED FROM REPEATED MEASURES MODEL USING 1-MIN MEANS WHERE STAGE WAS INCLUDED AS TIME-VARYING COVARIATE

| SBP

|

DBP

|

MAP

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | F Value | P Value | F Value | P Value | F Value | P Value |

| Group | 22.64 | <0.0001 | 9.52 | <0.0001 | 15.37 | <0.0001 |

| Stage | 193.89 | <0.0001 | 213.03 | <0.0001 | 226.19 | <0.0001 |

| Group by stage | 4.86 | <0.0001 | 2.14 | 0.0461 | 3.46 | 0.0020 |

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.8554 | 3.46 | 0.0637 | 1.70 | 0.1932 |

| Age | 24.10 | <0.0001 | 26.75 | <0.0001 | 27.83 | <0.0001 |

| Race | 5.48 | 0.0198 | 0.03 | 0.8654 | 1.00 | 0.3178 |

| BMIZ | 1.15 | 0.2841 | 6.05 | 0.0143 | 3.62 | 0.0577 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMIZ = Body mass index Z score; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Determinants of ΔrSO2.

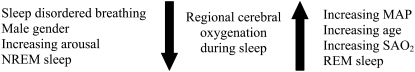

The repeated measures model used to determine predictors of ΔrSO2 identified sleep stages, age, sex, SaO2, MAP, and arousal index as significant. The direction of the association between ΔrSO2, and age, female sex, and MAP is such that these variables increased, while arousal index decreased rSO2. Relative to REM sleep, ΔrSO2 decreased during NREM sleep stages. Based on these findings, a model is proposed in which age, MAP, SaO2, and REM sleep diminish the decline in rSO2 during sleep and SDB status, male sex, arousal index, and NREM sleep augment the decline in rSO2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic of predictive model of regional cerebral oxygenation.

DISCUSSION

We have presented data that illustrate the complexity of the association between SDB and rSO2 in children. For example, although increasing arousal indices were associated with decreasing rSO2, increasing MAP was associated with increasing rSO2. Nevertheless, both increasing arousal indices and increasing MAP were strongly associated with SDB severity. These data suggest that SDB may have effects that both augment and diminish rSO2 in children. We have proposed a model that has the potential of explaining the variability in end-organ injury and neurocognitive deficits in children with SDB by identifying parameters with competing effects on rSO2 in children.

In the simplest model relating rSO2 to AHI, one would expect to find that rSO2 decreases as AHI increases. As such, we hypothesized that SDB would exert a dose-dependent, steady-state decrease in rSO2 during sleep. Interestingly, however, we found that children with primary snoring had significantly lower ΔrSO2 compared with those with OSA. A likely explanation for these findings is the positive association of ΔrSO2 levels with some of the physiologic parameters affected by SDB. Specifically, we found that ΔrSO2 had a positive association with MAP, SaO2, age, and REM sleep. SDB status, increasing arousals, NREM sleep, and male sex had a negative association with ΔrSO2. The absence of a significant difference in ΔrSO2 between control subjects and children with OSA could thus be attributed to the sum effect of these positive and negative associations in children with OSA.

We previously demonstrated that children with OSA have higher 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure compared with healthy control subjects (26). We also demonstrated that elevated ambulatory blood pressure is associated with cardiac remodeling. Collectively, these findings suggest that in the pre-hypertensive stage, elevated blood pressure in children with SDB may contribute to cardiac remodeling, but may also contribute to maintaining normal ΔrSO2. Paradoxically, these observations reveal a potential benefit of mild elevation in blood pressure in children with SDB. When evaluating the effect of SDB on neurocognitive function in children, it is thus essential to take blood pressure into account.

Analysis of the influence of demographic characteristics on ΔrSO2 demonstrated an important sex difference in ΔrSO2 in response to SDB status. Females were less likely to have a decline in rSO2 in the presence of SDB. These findings are consistent with many studies that demonstrate a natural sex advantage in cerebral blood flow. At all ages, blood flow to the cerebral hemispheres is greater in females compared with males (27–29). This difference remains statistically significant after adjusting for differences in unit weight of the brain (28). Furthermore, there is evidence of sex differences in the responses of cerebral blood flow to cortical stimulation or oxygen deprivation. In studies of cerebral blood flow using functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques, females demonstrate an enhanced regional cerebral flow in response to visual stimulation (29). Also, in an animal model of incomplete ischemia, females treated with exogenous estradiol maintain a higher cerebral blood flow during ischemia and lower postischemic hyperemia compared with untreated female and male animals (30–32). Taken together, these findings suggest that female sex hormones might have a protective effect against cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Thus, it is possible that a higher level of rSO2 during sleep in females results from a greater baseline cerebral flow. Also, we speculate that female sex hormones may have a protective effect in humans, as seen in animal models (31, 32).

Our analyses identified age as a significant positive predictor of rSO2. These results are consistent with those of Kobayashi and coworkers, who showed that regional cerebral blood flow increases with age in childhood (33). Other studies demonstrate that cerebral blood flow is higher in children than in adults (34). These studies corroborate the physical development of the brain, which grows most rapidly during childhood, and reaches a plateau around 12 years old. These results imply that normal cerebral growth could play an important role in modulating the effect of SDB on cerebral oxygenation in children.

There is convincing evidence that rSO2 levels measured by NIRS are similar to rSO2 levels measured by cerebral blood flow (21, 35–37), an important determinant of cerebral arterial perfusion pressure. The effect of blood flow on perfusion is influenced to a large extent by systemic blood pressure. Our study further highlighted the role of blood pressure in cerebral oxygenation, demonstrating that MAP exerts a strong positive association with rSO2 in children during sleep. Although the mechanisms of cerebral oxygenation were not explored, the results suggest that SDB status disturbs the relationship between oxygen supply and demand. Our results point to the likelihood that cerebral metabolic demands are increased in children with SDB.

The study design was based on the objective of measuring differences in rSO2 during sleep between children with SDB and matched control subjects. Although we achieved adequate matching on age, sex, and race between groups, more detailed data on pubertal status (Tanner staging [38]) might well have added valuable knowledge about age and sex interactions in modifying rSO2 during sleep.

Conclusions

The absence of a dose-dependent association of cognitive deficits with increasing severity of OSA may result from the complexity of the relationship between SDB and the parameters that affect rSO2. Regional cerebral oxygenation increased in children with increasing MAP, SaO2, and during REM sleep. Regional oxygenation is decreased in children with increasing SDB status, arousal index, during NREM sleep. Also, we found that rSO2 levels increased with age and were higher in females than in males. These physiologic and demographic data are incorporated into a predictive statistical model relating rSO2 to these parameters in children with SDB. This model may provide an approach to assessing neurocognitive morbidity of SDB in children.

Funding: RO1-HL70907–02A1 M01 RR 08084–08.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200802-321OC on July 24, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: M.A.K. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. K.M. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. R.V. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. V.S. has served as a consultant to Res Med, Respironics, Cardiac Concepts, Glaxo Smith Kline, and as a speaker at a meeting sponsored by Medtronics and one by Respironics. He is also an investigator on research grants from Sorin, Inc., Respironics Sleep and Breathing Foundation, and ResMed Foundation. M.F. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. S.Q. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. J.J. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. A.P.C. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.R. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. R.A. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kuehni CE, Strippoli MP, Chauliac ES, Silverman M. Snoring in preschool children: prevalence, severity and risk factors. Eur Respir J 2008;31:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:242–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beebe DW. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. Sleep 2006;29:1115–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beebe DW, Wells CT, Jeffries J, Chini B, Kalra M, Amin R. Neuropsychological effects of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004;10:962–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb DJ, Chase C, Vezina RM, Heeren TC, Corwin MJ, Auerbach SH, Weese-Mayer DE, Lesko SM. Sleep-disordered breathing symptoms are associated with poorer cognitive function in 5-year-old children. J Pediatr 2004;145:458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbower AC, Degaonkar M, Barker PB, Earley CJ, Marcus CL, Smith PL, Prahme MC, Mahone EM. Childhood obstructive sleep apnea associates with neuropsychological deficits and neuronal brain injury. PLoS Med 2006;3:e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill CM, Hogan AM, Onugha N, Harrison D, Cooper S, McGrigor VJ, Datta A, Kirkham FJ. Increased cerebral blood flow velocity in children with mild sleep-disordered breathing: a possible association with abnormal neuropsychological function. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1100–e1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karpinski AC, Scullin MH, Montgomery-Downs HE. Risk for sleep-disordered breathing and executive function in preschoolers. Sleep Med 2008;9:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, Bruner JL, Klaus CJ, Rutherford J, Raffield TJ, Gozal D. Neurobehavioral implications of habitual snoring in children. Pediatrics 2004;114:44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Archbold KH, Dillon JE. Snoring predicts hyperactivity four years later. Sleep 2005;28:885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Giordani BJ, Weatherly RA, Dillon JE, Hodges EK, Marcus CL, Guire KE. Sleep-disordered breathing, behavior, and cognition in children before and after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics 2006;117:e769–e778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadoi Y, Saito S, Goto F, Fujita N. Decrease in jugular venous oxygen saturation during normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass predicts short-term postoperative neurologic dysfunction in elderly patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1450–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshitani K, Kawaguchi M, Sugiyama N, Sugiyama M, Inoue S, Sakamoto T, Kitaguchi K, Furuya H. The association of high jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation with cognitive decline after hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg 2001;92:1370–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Placidi F, Diomedi M, Cupini LM, Bernardi G, Silvestrini M. Impairment of daytime cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. J Sleep Res 1998;7:288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2034–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Thoracic Society. Standards and indications for cardiopulmonary sleep studies in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:866–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagdyman N, Ewert P, Peters B, Miera O, Fleck T, Berger F. Comparison of different near-infrared spectroscopic cerebral oxygenation indices with central venous and jugular venous oxygenation saturation in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2008;18:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berens RJ, Stuth EA, Robertson FA, Jaquiss RD, Hoffman GM, Troshynski TJ, Staudt SR, Cava JR, Tweddell JS, Bert Litwin S. Near infrared spectroscopy monitoring during pediatric aortic coarctation repair. Paediatr Anaesth 2006;16:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayakar A, Dunoyer C, Rey G, Yaylali I, Jayakar P. Near-infrared spectroscopy to define cognitive frontal lobe functions. J Clin Neurophysiol 2005;22:415–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQuillen PS, Nishimoto MS, Bottrell CL, Fineman LD, Hamrick SE, Glidden DV, Azakie A, Adatia I, Miller SP. Regional and central venous oxygen saturation monitoring following pediatric cardiac surgery: concordance and association with clinical variables. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2007;8:154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagdyman N, Fleck T, Bitterling B, Ewert P, Abdul-Khaliq H, Stiller B, Hubler M, Lange PE, Berger F, Schulze-Neick I. Influence of intravenous sildenafil on cerebral oxygenation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in infants after cardiac surgery. Pediatr Res 2006;59:462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura Y, Tanii H, Fukuda M, Kajiki N, Inoue K, Kaiya H, Nishida A, Okada M, Okazaki Y. Frontal dysfunction during a cognitive task in drug-naive patients with panic disorder as investigated by multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy imaging. Neurosci Res 2007;59:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng Y, Ding H, Gong Q, Jia Z, Huang L. Monitoring cerebral oxygen saturation during cardiopulmonary bypass using near-infrared spectroscopy: the relationships with body temperature and perfusion rate. J Biomed Opt 2006;11:024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rechtschaffen A, Kales R. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles, CA: BIS/BRI, UCLA; 1968. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Valipour A, McGown AD, Makker H, O'Sullivan C, Spiro SG. Some factors affecting cerebral tissue saturation during obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J 2002;20:444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin R, Somers VK, McConnell K, Willging P, Myer C, Sherman M, McPhail G, Morgenthal A, Fenchel M, Bean J, et al. Activity-adjusted 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and cardiac remodeling in children with sleep disordered breathing. Hypertension 2008;51:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cosgrove KP, Mazure CM, Staley JK. Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:847–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gur RC, Gur RE, Obrist WD, Hungerbuhler JP, Younkin D, Rosen AD, Skolnick BE, Reivich M. Sex and handedness differences in cerebral blood flow during rest and cognitive activity. Science 1982;217:659–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez G, Warkentin S, Risberg J, Rosadini G. Sex differences in regional cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1988;8:783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kastrup A, Li TQ, Glover GH, Kruger G, Moseley ME. Gender differences in cerebral blood flow and oxygenation response during focal physiologic neural activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999;19:1066–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurn PD, Littleton-Kearney MT, Kirsch JR, Dharmarajan AM, Traystman RJ. Postischemic cerebral blood flow recovery in the female: effect of 17 beta-estradiol. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1995;15:666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmon SC, Williams MJ, Littleton-Kearney MT, Traystman RJ, Kosk-Kosicka D, Hurn PD. Estrogen increases cGMP in selected brain regions and in cerebral microvessels. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998;18:1248–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi A, Ito M, Shiraishi H, Kishi K, Sejima H, Haneda N, Uchida N, Sugimura K. A quantitative study of regional cerebral blood flow in childhood using 123I-IMP-SPECT: with emphasis on age-related changes. No To Hattatsu 1996;28:501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biagi L, Abbruzzese A, Bianchi MC, Alsop DC, Del Guerra A, Tosetti M. Age dependence of cerebral perfusion assessed by magnetic resonance continuous arterial spin labeling. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007;25:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bucher HU, Edwards AD, Lipp AE, Duc G. Comparison between near infrared spectroscopy and 133Xenon clearance for estimation of cerebral blood flow in critically ill preterm infants. Pediatr Res 1993;33:56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meybohm P, Hoffmann G, Renner J, Boening A, Cavus E, Steinfath M, Scholz J, Bein B. Measurement of blood flow index during antegrade selective cerebral perfusion with near-infrared spectroscopy in newborn piglets. Anesth Analg 2008;106:795–803. (table of contents.). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tachtsidis I, Tisdall M, Delpy DT, Smith M, Elwell CE. Measurement of cerebral tissue oxygenation in young healthy volunteers during acetazolamide provocation: a transcranial Doppler and near-infrared spectroscopy investigation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008;614:389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH. Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Arch Dis Child 1976;51:170–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]