Fig. 5.

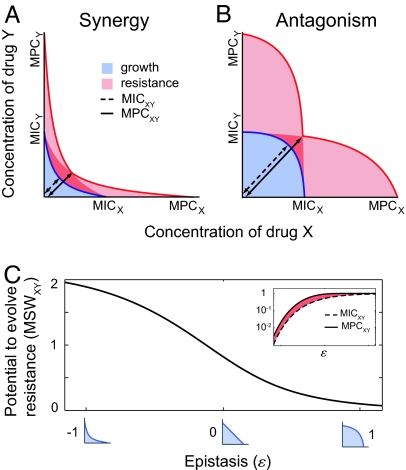

Synergy is predicted to be less efficient than antagonism at reducing the potential for evolving resistance. We consider for simplicity a bacterial population containing only three subpopulations: the wild type, a mutant population resistant only to drug X, and a mutant population resistant only to drug Y (no double mutants or cross-resistance). (A and B) The frequency of resistance to combinations of X and Y strongly depends on their epistatic interactions (synergy in A, and antagonism in B). The MSW of the drug pair is defined by the smallest MSW of the “effective” drugs obtained by mixing X and Y at constant proportions. Here, in each case, the effective drug that possesses the smallest MSW is obtained for the proportion 1X:1Y (black lines with arrows). The MPC of that effective drug (solid line) is smaller relative to the MIC (dashed line) when the drug pair is antagonistic: the MSW of the combination is smaller for antagonistic than for synergistic epistasis. (C) The size of the MSW decreases as epistasis changes from synergy to antagonism. (Inset) This reduction in the size of the MSW (red) is a result of the MPC of the “best” effective drug (solid line) growing more slowly than its MIC (dashed line). As the epistatic interactions vary from synergy to antagonism, the MSW shrinks and eventually vanishes.