Abstract

The genes encoding gluconeogenic enzymes in the nonconventional yeast Yarrowia lipolytica were found to be differentially regulated. The expression of Y. lipolytica FBP1 (YlFBP1) encoding the key enzyme fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase was not repressed by glucose in contrast with the situation in other yeasts; however, this sugar markedly repressed the expression of YlPCK1, encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, and YlICL1, encoding isocitrate lyase. We constructed Y. lipolytica strains with two different disrupted versions of YlFBP1 and found that they grew much slower than the wild type in gluconeogenic carbon sources but that growth was not abolished as happens in most microorganisms. We attribute this growth to the existence of an alternative phosphatase with a high Km (2.3 mM) for fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. The gene YlFBP1 restored fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase activity and growth in gluconeogenic carbon sources to a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fbp1 mutant, but the introduction of the FBP1 gene from S. cerevisiae in the Ylfbp1 mutant did not produce fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase activity or growth complementation. Subcellular fractionation revealed the presence of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus.

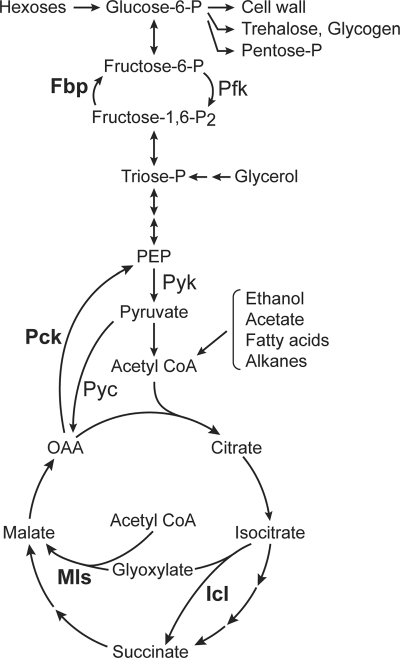

The growth of yeasts and other microorganisms in nonsugar carbon sources is dependent on gluconeogenesis. This pathway implicates specific gluconeogenic enzymes, such as fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (Fbp) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pck), that bypass the two physiologically irreversible steps in the glycolytic pathway, namely, phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase. In addition, under certain growth conditions, the enzymes from the glyoxylate cycle, isocitrate lyase (Icl) and malate synthase, are also required for the function of gluconeogenesis (Fig. 1). Growth in any nonsugar carbon source requires Fbp, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of fructose-1,6-P2 to fructose-6-phosphate, and therefore, Fbp is a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis. The simultaneous function of specific gluconeogenic enzymes and their glycolytic counterparts would lead to futile cycles, i.e., reactions that waste ATP without yielding a net product (42). Presumably due to evolutionary pressure, a series of control mechanisms have been selected to minimize the functioning of those cycles. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the activities of phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase are controlled by a series of activators and inhibitors whose concentrations vary upon growth on sugars or nonsugar carbon sources (12, 61, 65). The activity of gluconeogenic enzymes is determined by the interplay of a variety of mechanisms. The transcription of the genes encoding them is subjected to catabolite repression, a complex regulatory phenomenon that involves many proteins (13, 32, 41). In addition, in S. cerevisiae, most of the gluconeogenic enzymes undergo catabolite inactivation (27, 48, 50), a proteolytic degradation that destroys them after glucose addition. Control by metabolites appears to be restricted to Fbp that is inhibited by AMP (31) and by fructose-2,6-P2 (34), whose concentration increases rapidly during growth in glucose (25, 45).

FIG. 1.

Scheme of gluconeogenesis and glycolysis in yeasts. Specific gluconeogenic enzymes are indicated in bold letters. When appropriate, their glycolytic counterparts are indicated. Pyruvate carboxylase (Pyc), an anaplerotic enzyme, might be needed both in gluconeogenesis and in glycolysis, depending on the carbon source. Fbp, fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase; Pfk, phosphofructokinase; Pyk, pyruvate kinase; Icl, isocitrate lyase; Mls, malate synthase; OAA, oxaloacetate.

The dimorphic yeast Yarrowia lipolytica is an organism of great biotechnological interest due to its ability to excrete organic acids and proteins to the medium (5). It is able to grow in a variety of nonsugar carbon sources, indicating the function of an active gluconeogenesis. This characteristic, and the fact that phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase, which catalyze the physiologically irreversible steps in glycolysis, present kinetic properties quite different from those of their homologous S. cerevisiae enzymes (22, 38), led us to initiate a study of the regulation of gluconeogenesis in Y. lipolytica with particular attention to that of its terminal enzyme Fbp. Our results show that in Y. lipolytica, glucose does not repress the gene encoding Fbp but represses those encoding Pck and Icl. Although in this yeast there is only one gene encoding a protein showing sequence similarity with other Fbps, we have found that its disruption did not lead to the inability to grow in gluconeogenic carbon sources in contrast with the situation in most microorganisms (1, 24, 30, 58-60, 64). We also found that a fraction of Fbp has a nuclear localization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, culture conditions, and plasmids.

The following yeast strains were used: Y. lipolytica CLIB89 (Collection de Levures d′Interêt Biotechnologique, Grignon, France; provided by C. Gaillardin), its derivative P01a MATA leu2-270 ura3-302 (4) (provided by A. Domínguez, Salamanca, Spain), and H222-S4 (provided by G. Barth, Dresden, Germany) and S. cerevisiae W303-1A ade2 ura3 leu2 trp1 his3 and CJM197 fbp1::HIS3 (29). The yeasts were grown at 30°C with shaking either in rich YP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) or in minimal YNB medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base [Difco, Detroit, MI], 0.1% glutamate) with 2% glucose, 3% glycerol, or 2% ethanol as a carbon source. Auxotrophic requirements were added at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. The transformation of the yeasts was done as described by Barth and Gaillardin (4) for Y. lipolytica and by Ito et al. (40) for S. cerevisiae. The following plasmids were constructed to create new strains of Y. lipolytica or S. cerevisiae: pRJ43 was used to integrate the Y. lipolytica FBP1 (YlFBP1) gene into the YlLEU2 locus of strain RJM001 (see below) to give strain RJM004. A 3,258-bp DNA fragment carrying 1,264 bp upstream of the initial YlFBP1 ATG, the YlFBP1 open reading frame (ORF), and 600 bp downstream of the stop codon was inserted into plasmid pINA354B (11) digested with ClaI and NotI and blunt ended. pRJ43 was digested with ApaI to direct it to the YlLEU2 locus. Plasmid pCL200 carries the YlFBP1 ORF under the control of the YlTEF1 promoter in plasmid pCL49 (21) and upon transformation of strain RJM002 (see below) originated strain CJM540. Plasmid pCL201 is an episomal plasmid that carries a 600-bp SmaI-EcoRV DNA fragment from the S. cerevisiae FBP1 (ScFBP1) promoter and the first 18 codons of ScFBP1 in frame with the YlFBP1 ORF in plasmid pDB20 (7) digested with SmaI and NotI; pCL202 is similar to pCL201 but carries only the ScFBP1 promoter fragment; pCL203 expresses the YlFBP1 ORF under the control of the ScADH1 promoter in the episomal plasmid pDB20 (7); and pCL204 is similar but with YlFBP1 in the inverted orientation. Other plasmids used were pRG6, an episomal plasmid bearing the S. cerevisiae FBP1 gene (16), and pINA237, which carries the YlLEU2 gene (23).

Isolation of the YlFBP1 gene.

Since the sequence of the gene encoding Fbp in Y. lipolytica was not available at the start of this work, it was isolated using degenerate oligonucleotides matching two regions of conserved amino acid sequences in Fbps, SEEQED and FEQAGG, and considering the Y. lipolytica codon bias (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/). Chromosome walking and PCR allowed the isolation of a DNA fragment of 3,254 bp comprising the YlFBP1 coding region, 1,232 bp upstream, and 1,006 bp downstream. This fragment was cloned into plasmid pGEM-T Easy (Promega) to give plasmid pRJ50.

Disruption of the chromosomal YlFBP1 copy.

Two different disruption cassettes were prepared: one with YlURA3 and other with YlLEU2. Plasmid pRJ50 was digested with BamHI, blunt ended, and ligated to a blunt-ended 1.7-kb SalI fragment carrying the YlURA3 gene obtained from plasmid pINA156 (57) to produce plasmid pRJ38A. A DNA fragment of 5,221 bp obtained by the digestion of pRJ38A with NotI was used to transform Y. lipolytica, producing strain RJM001. To generate a disruption cassette with YlLEU2, we introduced by PCR an NcoI site 125 bp upstream of the initial YlFBP1 ATG (see Fig. 4A) in pRJ50. A 984-bp fragment from the YlFBP1 gene was replaced with an NcoI fragment of 2,100 bp carrying the YlLEU2 gene obtained from plasmid pINA62 (28) to give plasmid pRJ39B. A digestion of pRJ39B with NotI produced a 4,370-bp DNA fragment that was used to transform Y. lipolytica-originating strain RJM002. Strain RJM003 is RJM001 with YlLEU2 reintroduced in the genome.

FIG. 4.

Nuclear localization of a fraction of YlFbp. An extract of glucose-grown Y. lipolytica strain P01a was fractionated into total (T), cytoplasmic (C), and nuclear (N) fractions as described in Materials and Methods. Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) of the different fractions were used for Western blot analysis carried out with specific antibodies against YlFbp and proteins of known subcellular localization. Pyc, pyruvate carboxylase (cytosolic); Nop, nucleolar protein 1 (nuclear).

Integration of a YlFBP1 promoter-lacZ fusion into the YlLEU2 locus.

A 1,300-bp DNA fragment upstream of the initial ATG of YlFBP1 was obtained by PCR, inserted into plasmid pINA354B (11), and digested with NotI and BamHI; the resulting plasmid was digested with ApaI to direct the insertion to the chromosomal YlLEU2 locus and used to transform strains P01a and RJM001 to give strains RJM007 and RJM008, respectively.

Preparation of antibodies against YlFbp.

A YlFBP1-GST fusion was expressed in Escherichia coli in the commercial plasmid pGEX4T2 (GE Health Care). The fusion protein was purified from the extract, and the YlFbp protein was isolated by electrophoresis after excision of the GST portion with thrombin. The identity of the protein was checked by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight. The protein was used to immunize mice, and antibodies were obtained by standard procedures.

Nucleic acid manipulations.

For Northern analysis, the yeasts were filtered and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen according to the procedure of Belinchón et al. (8). Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol-LS reagent (Invitrogen), separated on 1.5% agarose-formaldehyde gels, and transferred to Nytran filters (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The probes were labeled with 32P using the Rediprime II random prime labeling kit (GE Health Care).

Probes for Northern analysis.

The following probes obtained by PCR using genomic Y. lipolytica DNA and adequate oligonucleotides were used: for YlFBP1, a 1,025-bp fragment corresponding to the ORF; for YlPCK1, a 230-bp fragment starting 226 bp after the initial ATG; for YlICL1, a 1,466-bp fragment starting 38 bp before the initial ATG; and for 18S rRNA, an 840-bp fragment described in reference 8.

Extracts and assay of enzyme activities.

Extracts were prepared by breaking the yeast with glass beads in 20 mM imidazole (pH 7) in five cycles of 1 min of vortexing and 1 min on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged in the cold for 15 min at 13,000 rpm in an Eppendorf tabletop centrifuge, and enzyme activities in the supernatants were assayed. Fbp was assayed as described by Gancedo and Gancedo (33), Pck as indicated by Perea and Gancedo (53), and Icl as described by Dixon and Kornberg (18). The protein level was determined using a commercial bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit.

Extraction and determination of intracellular metabolites.

About 200 mg (wet weight) yeast cells was rapidly filtered in a vacuum through a 0.8-μm-pore-diameter Millipore filter AAWPO4700 and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The pellets were treated with boiling ethanol as in Gamo et al. (29) and the metabolites determined by spectrophotometric methods (10). For calculations, it was assumed that 1 g wet yeast has an intracellular volume of 0.6 ml (14).

Subcellular fractionation.

The cells were converted to spheroplasts with Zymolyase, lysed gently, and fractionated basically as described in reference 55 through a combination of Ficoll and Percoll gradients with an additional centrifugation step at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C to eliminate Percoll from the nuclear fraction. Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and hybridized to different specific antibodies.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the YlFBP1 gene has been deposited in GenBank with the accession number AY324116.

RESULTS

Effect of carbon sources on the activity of gluconeogenic enzymes in Y. lipolytica.

We assayed the activities of two gluconeogenic enzymes, Fbp and Pck, and the glyoxylate cycle enzyme Icl whose activity is repressed by glucose (6, 49) in Y. lipolytica grown in different carbon sources. The activity of Fbp was similar in extracts from cells grown in glucose or in gluconeogenic carbon sources (Table 1). This result contrasts with those found in other yeasts in which Fbp is repressed by glucose (20, 39, 60). Pck and Icl activities were much lower in cells grown in glucose or glycerol than in those grown in ethanol or acetate (Table 1), showing that these enzymes are subject to catabolite repression as in other yeasts (3, 20, 36, 43, 47). However, catabolite repression was not as drastic as in S. cerevisiae; a residual activity in glucose-grown cultures that could reach ca. 30% of the derepressed value was always observed. The low values of Pck and Icl in cultures grown in glycerol reflect their position in metabolism (Fig. 1). The similar values of YlFbp in cultures with glucose or with gluconeogenic carbon sources were not a peculiarity of the strain used; a similar pattern was observed in two other Y. lipolytica strains of different origin and genetic background (results not shown).

TABLE 1.

Specific activities of gluconeogenic enzymes of Y. lipolytica grown in different carbon sourcesa

| Enzyme | Sp act (mU/mg protein)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose

|

Glycerol

|

Ethanol

|

Acetate

|

|||||

| YNB | YP | YNB | YP | YNB | YP | YNB | YP | |

| Fbp | 123 ± 12 | 80 ± 8 | 111 ± 11 | 115 ± 12 | 106 ± 6 | 98 ± 8 | 91 ± 8 | 99 ± 5 |

| Pck | 36 ± 3 | 13 ± 6 | 20 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 280 ± 25 | 290 ± 11 | 164 ± 30 | 155 ± 20 |

| Icl | 73 ± 10 | 32 ± 5 | 45 ± 10 | 30 ± 4 | 438 ± 27 | 300 ± 33 | 228 ± 32 | 145 ± 19 |

Y. lipolytica wild-type strain P01a was grown with the indicated carbon sources in minimal or rich media as described in Materials and Methods and harvested in the exponential phase of growth. Extracts and enzymatic assays were done as described in Materials and Methods. Figures are the mean values ± the standard errors of the means of the results from four independent cultures.

Cloning of the gene YlFBP1 and properties of its encoded protein.

A DNA fragment of ca. 600 bp obtained by PCR using genomic DNA from Y. lipolytica strain P01a as a template and degenerate oligonucleotides was used to isolate the whole gene as described in Materials and Methods. An ORF of 1,017 bp that encodes a protein of 339 amino acids with a 60 to 70% amino acid sequence identity with Fbps from other yeasts was obtained; the corresponding gene has been named YlFBP1. We found variations in the sequence of YlFBP1 among strains of different origin; at amino acid 69, the DNA sequences of CLIB89 and of P01a read GCA, while those of H222-S4 and the one deposited in the Genolevures (http://cbi.labri.fr/Genolevures/) database read GCC (silent mutation). At amino acid 229, CLIB89 and P01a read AAC, while the others read GAC (change from D to N in the amino acid sequence).

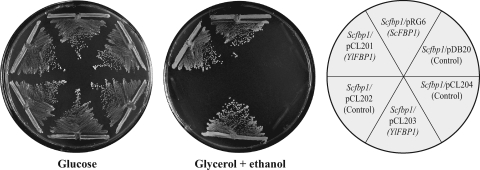

The YlFBP1 gene restored Fbp activity to an S. cerevisiae fbp1 mutant and complemented its growth defect in gluconeogenic carbon sources (Fig. 2). When it was expressed under the control of the YlTEF1 promoter in Y. lipolytica, Fbp activity increased up to 1,200 mU/mg protein. In contrast, the S. cerevisiae FBP1 gene expressed under the control of the YlTEF1 promoter did not complement the growth defect of a Ylfbp1 mutant.

FIG. 2.

Phenotypic complementation of an S. cerevisiae fbp1 mutant by expression of the YlFBP1 gene. An S. cerevisiae fbp1 mutant (strain CJM197) was transformed with plasmids carrying the ScFBP1 gene (pRG6 [16]), no insertion (pDB20 [7]), the YlFBP1 gene under the control of the ScFBP1 promoter (pCL201), the ScFBP1 promoter (pCL202), the YlFBP1 gene under the control of the ScADH1 promoter (pCL203), or a similar plasmid with the YlFBP1 gene in the inverted orientation (pCL204). A purified transformant of each was streaked on plates with glucose or with glycerol plus ethanol as carbon sources. Specific Fbp activities (each given as the mean of two independent cultures) in mU/mg protein were 250 for S. cerevisiae with pRG6, 550 for S. cerevisiae with pCL201, 80 for S. cerevisiae with pCL203, and <1 for S. cerevisiae with control plasmids. For a detailed description of the plasmids, see Materials and Methods.

A preliminary kinetic characterization of YlFbp was done using dialyzed extracts after treatment with protamine sulfate. A Km of 30 μM for fructose-1,6-P2 was calculated, a value in the range found for other Fbps (9, 31, 52, 63). The activity was inhibited by AMP (Ki, 0.8 mM) or fructose-2,6-P2 (50% inhibition at 0.18 μM in the presence of 0.2 mM fructose-1,6-P2). These characteristics support the idea that the activity considered corresponds to a typical Fbp.

Expression of YlFBP1 and levels of YlFbp in Y. lipolytica.

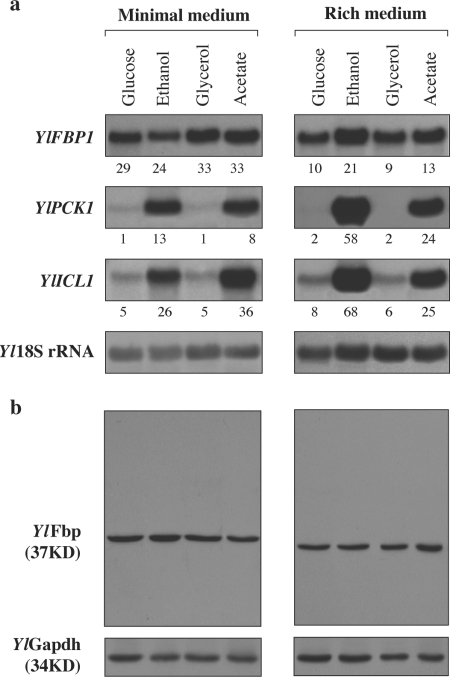

We studied the expression of the YlFBP1 gene in different carbon sources using Northern blotting and by measuring the β-galactosidase activities produced by a fusion of the YlFBP1 promoter to the E. coli lacZ gene integrated into the chromosomal YlLEU2 locus. The result of the Northern analysis is shown in Fig. 3. The probe against YlFBP1 revealed a unique band whose intensity did not vary markedly with the carbon source used for growth, a result consistent with that of the enzyme values (Table 1). Also, a Western analysis using a specific antibody against YlFbp showed that the amount of this protein was similar in all growth conditions used (Fig. 3). These results show that catabolite repression does not affect the levels of the YlFBP1 mRNA and that YlFbp is not subject to catabolite inactivation.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the expression of gluconeogenic genes from Y. lipolytica grown in different carbon sources and Western analysis of YlFbp. Y. lipolytica strain P01a was grown either in minimal or rich medium with the indicated carbon sources, harvested in the late exponential phase of growth, and treated as described in Materials and Methods. (a) The membrane with the separated RNAs was hybridized with probes corresponding to the YlFBP1, YlPCK1, YlICL1, and Y. lipolytica 18S rRNA genes (the last one as a loading control; see Materials and Methods). The numbers under the bands show the corresponding intensities (cpm/mm2) normalized against those of the control. (b) Immunodetection of YlFbp. Extracts were subjected to PAGE and probed with a specific antibody against YlFbp (see Materials and Methods). As a loading control, incubation with an antibody against Y. lipolytica GAPDH was used.

When β-galactosidase was expressed under the control of the YlFBP1 promoter, there was a 1.5- to 2.5-fold increase in activity in cells grown in ethanol or acetate with respect to glucose- or glycerol-grown cells, both in minimal and in rich medium (Table 2). The difference between the changes in β-galactosidase activity and the data on Fbp activity and Western and Northern analysis could be explained by an increased instability of YlFBP1 mRNA in media with ethanol or acetate. The activities of β-galactosidase measured in a strain with a disrupted YlFBP1 followed the same trend as those found in a wild type, but the activities were always higher (between three to eight times) than in a wild-type background (Table 2). These results may be interpreted in two ways that are not mutually exclusive: either YlFbp controls the activity of its own promoter, or the metabolic disturbance caused by the lack of the enzyme affects the expression of YlFBP1.

TABLE 2.

Specific activity of β-galactosidase (mU/mg protein) produced from an integrated YlFBP1 promoter-lacZ fusion in Y. lipolytica grown in different carbon sourcesa

| Strain and relevant genotype | Sp act (mU/mg protein) of β-galactosidase

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose

|

Glycerol

|

Ethanol

|

Acetate

|

|||||

| YNB | YP | YNB | YP | YNB | YP | YNB | YP | |

| RJM007 YlFBP1 | 36 ± 5 | 14 ± 4 | 47 ± 4 | 12 ± 1 | 83 ± 6 | 36 ± 3 | 70 ± 5 | 23 ± 5 |

| RJM008 Ylfbp1::URA3 | 97 ± 13 | 33 ± 2 | 94 ± 15 | 23 ± 5 | 297 ± 15 | 182 ± 6 | 372 ± 13 | 189 ± 10 |

Y. lipolytica strains RJM007 and RJM008, wild type and Ylfbp1::URA3, respectively, bearing a fusion of the YlFBP1 promoter to the E. coli lacZ integrated into the chromosomal YlLEU2 locus (see Materials and Methods) were cultured in minimal or rich medium with the indicated carbon sources, and β-galactosidase was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are the mean values ± the standard errors of the means of the results from four independent cultures.

If YlFbp participates in the regulation of the expression of YlFBP1, it could be expected that a fraction of it will be found in the yeast nucleus. To test this possibility, we did a subcellular fractionation and followed the distribution of Fbp in different fractions using a specific YlFbp antibody. As shown in Fig. 4, YlFbp was detected in the nuclear fraction; the lack of cytoplasmic contamination in this fraction was shown by the absence of reaction with an antibody against pyruvate carboxylase, a cytoplasmic protein in yeast (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained with nuclei prepared from cells grown in glucose or in ethanol. This result together with those of β-galactosidase activity would be suggestive of a moonlighting role for YlFbp.

The results obtained for YlFBP1 contrast with those found with probes against YlPCK1 and YlICL1 (Fig. 3) that showed a pattern of glucose repression in agreement with the values of enzymatic activity (Table 1). The results obtained show that expression of the genes encoding gluconeogenic enzymes in Y. lipolytica is not regulated in parallel and that it differs from that found in other yeasts.

Effects of the disruption of the YlFBP1 gene.

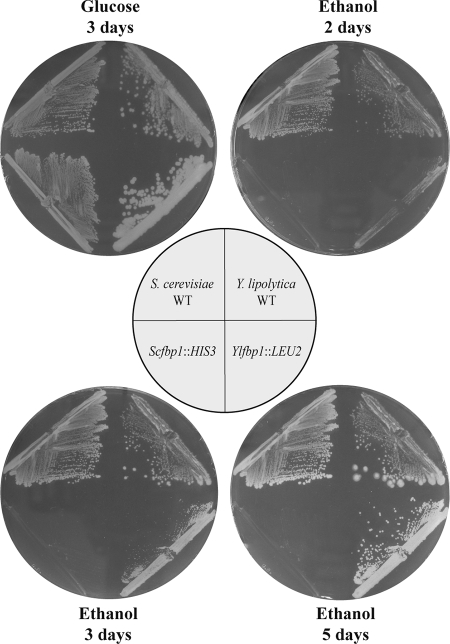

YlFBP1 was disrupted with two different cassettes (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 5). After transformation of the yeast and selection in glucose medium, the transformants were transferred to a medium with ethanol. Those that did not grow after 2 days were checked for the correctness of the disruption (Fig. 5). Also a Western blot of the disruptants showed no cross-reacting material against a specific YlFbp antibody (Fig. 5). These results indicate that YlFbp is the main activity implicated in the growth of Y. lipolytica in ethanol. However, Ylfbp1 disruptants grew after several days on ethanol plates, a behavior different than that of S. cerevisiae fbp1 mutants (Fig. 6). The growth was not due to the appearance of extragenic suppressors, as identical volumes of a cell suspension of a Ylfbp1 disruptant produced a similar number of colonies on plates with glucose, glycerol, or ethanol (result not shown).

FIG. 5.

Disruption of the chromosomal copy of the YlFBP1 gene and analysis of the disruptants. Scheme of the chromosomal region around YlFBP1 in wild-type strain P01a (a) and in strains RJM001 Ylfbp1::YlURA3 (b) or RJM002 Ylfbp1::YlLEU2 (c). The bold lines show the regions of DNA used for chromosomal disruptions. The NcoI site marked with an asterisk was created by PCR. (d) Southern analysis of the disruptants. Genomic DNA was digested with DraI. The 1,108-bp DNA fragment indicated as a probe was obtained by PCR. The sizes of the DNA bands are indicated. (e) Western blot analysis of YlFbp protein in the Ylfbp1::LEU2 disruptant. Extracts were subjected to PAGE and probed with a specific antibody against YlFbp. A loading control probed with an antibody against Y. lipolytica GAPDH is shown. WT, wild type.

FIG. 6.

Effect of the disruption of the FBP1 gene on the growth of Y. lipolytica and S. cerevisiae on ethanol. The following strains were streaked on minimal medium plates with glucose or ethanol as carbon sources and incubated at 30°C: Y. lipolytica wild-type (WT) P01a (upper right), RJM002 Ylfbp1::LEU2 (lower right), S. cerevisiae CJM 197 (Scfbp1::HIS3; lower left), and S. cerevisiae W303-1A (wild type, upper left). Pictures were taken 2, 3, and 5 days after the inoculation of Y. lipolytica; S. cerevisiae strains on the ethanol plate were inoculated 3 days before.

Since growth in gluconeogenic carbon sources requires the formation of fructose-6-P by Fbp, we determined if there was another phosphatase activity acting on fructose-1,6-P2 in the disrupted strain. We found such an activity that amounted to about 20% of the total wild-type Fbp activity. This result shows that in the absence of YlFbp, another phosphatase supports a slow growth in gluconeogenic conditions. No such activity was observed in an S. cerevisiae fbp1 mutant, even if the concentration of fructose-1,6-P2 in the assay was increased 50 times. The difference in generation times between the wild type and the YlFBP1 disruptant was more marked in ethanol (313 ± 11 min versus 460 ± 30) or acetate (190 ± 14 versus 293 ± 9) than in glycerol (123 ± 3 versus 142 ± 3). Reintroduction of the YlFBP1 gene in a Ylfbp1::URA3 mutant restored normal growth in ethanol, indicating that YlFbp is the phosphatase responsible for growth in gluconeogenesis. Additional evidence for this role is provided by the values of metabolites directly related to fructose-1,6-P2, the substrate of Fbp. As shown in Table 3, its concentration increased in the disruptant during growth in gluconeogenic substrates and the levels of hexose monophosphates decreased. The concentration of ATP tended to be higher in the disruptant, with the exception of the acetate cultures.

TABLE 3.

Intracellular concentration (mM) of several metabolites in Y. lipolyticaa

| Metabolite | Concentration (mM)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose

|

Glycerol

|

Ethanol

|

Acetate

|

|||||

| YlFBP1 | Ylfbp1 | YlFBP1 | Ylfbp1 | YlFBP1 | Ylfbp1 | YlFBP1 | Ylfbp1 | |

| Glucose-6-P | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.43 ± 0.10 | 0.50 ± 0.10 | 0.13 ± 0.2 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| Fructose-6-P | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | ≤0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | ≤0.02 |

| Fructose-1,6-P2 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.06 |

| ATP | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 0.70 ± 0.10 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.64 ± 0.03 |

A wild-type strain of Y. lipolytica (P01a) and a Ylfbp1::LEU2 strain (RJM002) were cultured in rich medium with the indicated carbon sources and harvested during the exponential phase (optical density, 0.8 to 1). Metabolites were assayed after extraction as described in Materials and Methods. Results are the mean values ± the standard errors of the means of the results from four independent cultures.

The YlFBP1 disruptants did not show microscopic differences in liquid cultures, but colonies on gluconeogenic substrates were smoother than those of the wild type (results not shown).

Some characteristics of the alternative phosphatase.

The available genomic sequence of Y. lipolytica (http://cbi.labri.fr/Genolevures/) does not reveal proteins with significant sequence homology to YlFbp1, indicating that the activity detected in the Ylfbp1 mutant is due to a different type of phosphatase. Its activity did not vary with the carbon source (results not shown) and was not lost in extracts from protoplasts, thus ruling out an extracellular location. A preliminary kinetic characterization, using extracts from Ylfbp1 cells precipitated with protamine sulfate and dialyzed, showed an optimum pH of 7.2, a Km for fructose-1,6-P2 of 2.3 mM, and no inhibition by AMP or fructose-2,6-bisphosphate. In some archaea, Fbp activity was ascribed to an inositol monophosphatase (62); since inositol monophosphatases are sensitive to Li+ (46), we checked whether the activity in extracts of Ylfbp1 mutants showed this property. The alternative phosphatase was about 25 times less sensitive to inhibition by Li+ than YlFbp; 25 mM LiCl inhibited its activity only by 50%.

DISCUSSION

We have identified and cloned the YlFBP1 gene encoding Fbp in Y. lipolytica. The strong identity in protein sequence with Fbps of diverse origin, the decrease in Fbp activity in a strain with a disrupted YlFBP1, the slow growth of this strain in gluconeogenic carbon sources, the complementation of the growth phenotype of an S. cerevisiae fbp1 mutant, and the increase in Fbp activity when YlFBP1 is overexpressed in Y. lipolytica or in S. cerevisiae show that the gene encodes this protein. The ScFBP1 gene did not restore growth on gluconeogenic carbon sources to a Ylfbp1 mutant. The marked difference in codon bias between the two yeasts (19) may offer a possible explanation for this result.

An examination of the available genomic sequence of Y. lipolytica indicated that there is only one gene encoding a bona fide Fbp. However, the growth of a Ylfbp1 mutant in nonsugar carbon sources, although slower than the wild type, contrasts with the lack of growth in these media observed in microorganisms lacking Fbp activity (1, 20, 24, 30, 58, 59, 64). The explanation for this growth is the existence of an alternative phosphatase with a high Km for fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. We do not know presently the gene encoding this activity, but its kinetic characteristics suggest that it encodes a protein unrelated to classical fructose-1,6-bisphosphatases. A phosphatase, even unspecific, acting on fructose-1,6-P2 could support the growth of an fbp1 mutant on gluconeogenic substrates as shown for E. coli, where a mislocalized phosphatase alleviated the growth defect of such a mutant (17). No information is available on the enzyme(s) that allow the growth of a Bacillus subtilis mutant lacking Fbp in glycerol or malate (26). The slower growth of the Ylfbp mutant in ethanol compared with that observed in glycerol could be due to the differences in the concentration of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate found in both conditions.

We have also shown that the expression of the genes encoding gluconeogenic enzymes in Y. lipolytica is not regulated in parallel and that YlFBP1 is not repressed by glucose. Catabolite repression is very strong in S. cerevisiae (13, 32, 41) and depends on a high glycolytic flux (29, 56). The low glycolytic capacity of Y. lipolytica compared to that of S. cerevisiae could explain the incomplete repression of YlPCK1 or YlICL1 in Y. lipolytica. But the lack of repression of YlFBP1 is almost complete and suggests that this protein has other roles besides its metabolic one. The lack of catabolite repression of the gene YlFBP1 and the partial expression of YlPCK1 during growth in glucose pose the problem of the waste of energy by the function of futile cycles. S. cerevisiae strains with functional futile cycles are viable but are at a disadvantage in competition with a wild-type strain (51). No measurement of futile cycles has been done yet for Y. lipolytica; however, their functioning during growth in glucose cannot be ruled out. In some bacteria like E. coli (24), Bacillus subtilis (26), or Corynebacterium glutamicum (58), the levels of Fbp did not vary with the carbon source, but futile cycles appear to be avoided by allosteric control of the corresponding enzymes (15, 37, 58). YlFbp is strongly inhibited by fructose-2,6-P2, and this inhibition could minimize the function of the cycle. Although AMP is a potent inhibitor of most Fbps, its role in the regulation of the yeast enzyme is not obvious, since its concentration does not show great variations between gluconeogenic and glycolytic conditions (2). Hines et al. (37) have shown that in E. coli, the inhibition of Fbp by AMP is increased up to 10 times upon the binding of glucose-6-phosphate, levels of which vary markedly between glycolytic and gluconeogenic growth conditions, thus making the sugar phosphate the actual controller of Fbp. These authors suggested that a similar situation may occur with AMP and fructose-2,6-P2 in eukaryotic organisms. Phosphoenolpyruvate was without significant effect on the enzyme of Y. lipolytica and this behavior is consistent with the finding that the phosphoenolpyruvate binding site is not present in Fbps from organisms that use fructose-2,6-P2 in the regulation of Fbp activity (37).

We have found that a fraction of YlFbp is present in the nucleus; this finding and the differences in β-galactosidase activity when expressed under the control of the YlFBP1 promoter in wild-type cells and in the Ylfbp1 mutant could suggest that YlFbp may have functions other than its pure metabolic one. In some higher eukaryotes, Fbp has been found to be associated with nuclei in different types of cells (35, 66). In some cases, the localization of the protein was influenced by the growth phase of the cells (35) or by changing metabolic conditions (66). A well-defined explanation for the presence of Fbp in the nucleus has not yet been advanced. Several studies on Y. lipolytica have revealed important differences in the properties of different enzymes implicated in carbohydrate metabolism like hexokinase (54), phosphofructokinase (22), 3-P-glycerate kinase (44), pyruvate kinase (38), or pyruvate carboxylase (21) with respect to those of their homologues in S. cerevisiae. The different properties in the regulation of the expression of genes encoding gluconeogenic enzymes and in the behavior of the Ylfbp1 mutants described in this work further stress the physiological differences between this yeast and the model yeast S. cerevisiae.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juana M. Gancedo (Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas Alberto Sols CSIC-UAM) for critical reading of the manuscript and discussions during the work; C. Gaillardin, J. M. Nicaud, S. Blanchin-Roland (INRA, Grignon, France), G. Barth (University of Dresden, Germany), P. Herrero, and F. Moreno (University of Oviedo, Spain) for the gift of biological materials; C. Gil (Dept. of Microbiology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Madrid) for identifying the YlFbp band by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight; A. Otero (University of Havana, Cuba) for help in the preparation of antibodies against YlFbp; A. Soukri (University Hassan II, Casablanca, Morocco) for the gift of the antibody against Y. lipolytica GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase); J. C. Wallace (University of Western Australia, Australia) for the gift of the antibody against Pyc; and J. De la Cruz (University of Seville, Spain) for a sample of antibody against Nop1.

This work was partially supported by grant BFU 2004-02855-C02-1 from the Spanish Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica to C.G. R.J. benefited from a fellowship of Formación de Profesorado Universitario from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitt, S., W. McCullough, and C. F. Roberts. 1976. Analysis of acetate non-utilizing (acu) mutants in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 92263-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bañuelos, M., C. Gancedo, and J. M. Gancedo. 1977. Activation by phosphate of yeast phosphofructokinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2526394-6398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barelle, C. J., C. L. Priest, D. M. Maccallum, N. A. Gow, F. C. Odds, and A. J. Brown. 2006. Niche-specific regulation of central metabolic pathways in a fungal pathogen. Cell. Microbiol. 8961-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barth, G., and C. Gaillardin. 1996. Yarrowia lipolytica, p. 313-388. In K. Wolf (ed.), Nonconventional yeasts in biotechnology. A handbook. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 5.Barth, G., and C. Gaillardin. 1997. Physiology and genetics of the dimorphic fungus Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 19219-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barth, G., and T. Scheuber. 1993. Cloning of the isocitrate lyase gene (ICL1) from Yarrowia lipolytica and characterization of the deduced protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 241422-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker, D. M., J. D. Fikes, and L. Guarente. 1991. A cDNA encoding a human CCAAT-binding protein cloned by functional complementation in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 881968-1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belinchón, M. M., C. L. Flores, and J. M. Gancedo. 2004. Sampling Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells by rapid filtration improves the yield of mRNAs. FEMS Yeast Res. 4751-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benkovic, S. J., and M. M. de Maine. 1982. Mechanism of action of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 5345-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmeyer, H. U., J. Bergmeyer, and M. Grassi. 1987. Methods in enzymatic analysis, 3rd ed., vol. VI and VII. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim, Germany.

- 11.Blanchin-Roland, S., R. R. Cordero Otero, and C. Gaillardin. 1994. Two upstream activation sequences control the expression of the XPR2 gene in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14327-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond, C. J., M. S. Jurica, A. Mesecar, and B. L. Stoddard. 2000. Determinants of allosteric activation of yeast pyruvate kinase and identification of novel effectors using computational screening. Biochemistry 3915333-15343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson, M. 1999. Glucose repression in yeast. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conway, E. J., and M. Downey. 1950. pH values of the yeast cell. Biochem. J. 47355-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daldal, F., and D. G. Fraenkel. 1983. Assessment of a futile cycle involving reconversion of fructose 6-phosphate to fructose 1,6-bisphosphate during gluconeogenic growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 153390-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de la Guerra, R., M. D. Valdés-Hevia, and J. M. Gancedo. 1988. Regulation of yeast fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in strains containing multicopy plasmids coding for this enzyme. FEBS Lett. 242149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derman, A. I., W. A. Prinz, D. Belin, and J. Beckwith. 1993. Mutations that allow disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Science 2621744-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon, G. H., and H. L. Kornberg. 1959. Assay methods for key enzymes of the glyoxylate cycle. Biochem. J. 723P. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dujon, B., D. Sherman, G. Fischer, P. Durrens, S. Casaregola, I. Lafontaine, J. De Montigny, C. Marck, C. Neuveglise, E. Talla, N. Goffard, L. Frangeul, M. Aigle, V. Anthouard, A. Babour, V. Barbe, S. Barnay, S. Blanchin, J. M. Beckerich, E. Beyne, C. Bleykasten, A. Boisrame, J. Boyer, L. Cattolico, F. Confanioleri, A. De Daruvar, L. Despons, E. Fabre, C. Fairhead, H. Ferry-Dumazet, A. Groppi, F. Hantraye, C. Hennequin, N. Jauniaux, P. Joyet, R. Kachouri, A. Kerrest, R. Koszul, M. Lemaire, I. Lesur, L. Ma, H. Muller, J. M. Nicaud, M. Nikolski, S. Oztas, O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, S. Pellenz, S. Potier, G. F. Richard, M. L. Straub, A. Suleau, D. Swennen, F. Tekaia, M. Wesolowski-Louvel, E. Westhof, B. Wirth, M. Zeniou-Meyer, I. Zivanovic, M. Bolotin-Fukuhara, A. Thierry, C. Bouchier, B. Caudron, C. Scarpelli, C. Gaillardin, J. Weissenbach, P. Wincker, and J. L. Souciet. 2004. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature 43035-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eschrich, D., P. Kötter, and K. D. Entian. 2002. Gluconeogenesis in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flores, C. L., and C. Gancedo. 2005. Yarrowia lipolytica mutants devoid of pyruvate carboxylase activity show an unusual growth phenotype. Eukaryot. Cell 4356-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flores, C. L., O. H. Martínez-Costa, V. Sánchez, C. Gancedo, and J. J. Aragón. 2005. The dimorphic yeast Yarrowia lipolytica possesses an atypical phosphofructokinase: characterization of the enzyme and its encoding gene. Microbiology 1511465-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fournier, P., L. Guyaneux, M. Chasles, and C. Gaillardin. 1991. Scarcity of ars sequences isolated in a morphogenesis mutant of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast 725-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraenkel, D. G., and B. L. Horecker. 1965. Fructose-1,6-diphosphatase and acid hexose phosphatase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 90837-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.François, J., P. Eraso, and C. Gancedo. 1987. Changes in the concentration of cAMP, fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and related metabolites and enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during growth on glucose. Eur. J. Biochem. 164369-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita, Y., and E. Freese. 1981. Isolation and properties of a Bacillus subtilis mutant unable to produce fructose-bisphosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 145760-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Funayama, S., J. M. Gancedo, and C. Gancedo. 1980. Turnover of yeast fructose-bisphosphatase in different metabolic conditions. Eur. J. Biochem. 10961-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaillardin, C., and A. M. Ribet. 1987. LEU2 directed expression of beta galactosidase activity and phleomycin resistance in Yarrowia lipolytica. Curr. Genet. 11369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gamo, F. J., M. J. Lafuente, and C. Gancedo. 1994. The mutation DGT1-1 decreases glucose transport and alleviates carbon catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 1767423-7429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gancedo, C., and M. A. Delgado. 1984. Isolation and characterization of a mutant from Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase. Eur. J. Biochem. 139651-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gancedo, C., M. L. Salas, A. Giner, and A. Sols. 1965. Reciprocal effects of carbon sources on the levels of an AMP-sensitive fructose-1,6-diphosphatase and phosphofructokinase in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gancedo, J. M. 1998. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62334-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gancedo, J. M., and C. Gancedo. 1971. Fructose-1,6-diphosphatase, phosphofructokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from fermenting and non fermenting yeasts. Arch. Mikrobiol. 76132-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gancedo, J. M., M. J. Mazón, and C. Gancedo. 1982. Kinetic differences between two interconvertible forms of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 218478-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gizak, A., E. Wrobel, J. Moraczewski, and A. Dzugaj. 2006. Changes in subcellular localization of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase during differentiation of isolated muscle satellite cells. FEBS Lett. 5804042-4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haarasilta, S., and E. Oura. 1975. On the activity and regulation of anaplerotic and gluconeogenetic enzymes during the growth process of baker's yeast. The biphasic growth. Eur. J. Biochem. 521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hines, J. K., H. J. Fromm, and R. B. Honzatko. 2006. Novel allosteric activation site in Escherichia coli fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 28118386-18393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirai, M., A. Tanaka, and S. Fukui. 1975. Difference in pyruvate kinase regulation among three groups of yeasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 391282-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Winston. 1991. Glucose repression of transcription of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe fbp1 gene occurs by a cAMP signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 5561-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston, M. 1999. Feasting, fasting and fermenting. Glucose sensing in yeast and other cells. Trends Genet. 1529-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katz, J., and R. Rognstad. 1976. Futile cycles in the metabolism of glucose. Curr. Top. Cell. Regul. 10237-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitamoto, H. K., S. Ohmomo, K. Amaha, T. Nishikawa, and Y. Limura. 1998. Construction of Kluyveromyces lactis killer strains defective in growth on lactic acid as a silage additive. Biotechnol. Lett. 20725-728. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Dall, M., J. Nicaud, B. Y. Treton, and C. M. Gaillardin. 1996. The 3-phosphoglycerate kinase gene of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica de-represses on gluconeogenic substrates. Curr. Genet. 29446-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lederer, B., S. Vissers, E. Van Schaftingen, and H. G. Hers. 1981. Fructose 2,6-bisphosphate in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1031281-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.López, F., M. Leube, R. Gil-Mascarell, J. P. Navarro-Avino, and R. Serrano. 1999. The yeast inositol monophosphatase is a lithium- and sodium-sensitive enzyme encoded by a non-essential gene pair. Mol. Microbiol. 311255-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.López, M. L., B. Redruello, E. Valdés, F. Moreno, J. J. Heinisch, and R. Rodicio. 2004. Isocitrate lyase of the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis is subject to glucose repression but not to catabolite inactivation. Curr. Genet. 44305-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.López-Boado, Y. S., P. Herrero, S. Gascón, and F. Moreno. 1987. Catabolite inactivation of isocitrate lyase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Microbiol. 147231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuoka, M., Y. Ueda, and S. Aiba. 1980. Role and control of isocitrate lyase in Candida lipolytica. J. Bacteriol. 144692-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Müller, M., H. Müller, and H. Holzer. 1981. Immunochemical studies on catabolite inactivation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 256723-727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Navas, M. A., and J. M. Gancedo. 1996. The regulatory characteristics of yeast fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase confer only a small selective advantage. J. Bacteriol. 1781809-1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Opheim, D. J., and R. W. Bernlohr. 1975. Purification and regulation of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Bacillus licheniformis. J. Biol. Chem. 2503024-3033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perea, J., and C. Gancedo. 1982. Isolation and characterization of a mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective in phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Arch. Microbiol. 132141-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petit, T., and C. Gancedo. 1999. Molecular cloning and characterization of the gene HXK1 encoding the hexokinase from Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast 151573-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rández-Gil, F., P. Herrero, P. Sanz, J. A. Prieto, and F. Moreno. 1998. Hexokinase PII has a double cytosolic-nuclear localization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 425475-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reifenberger, E., E. Boles, and M. Ciriacy. 1997. Kinetic characterization of individual hexose transporters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their relation to the triggering mechanisms of glucose repression. Eur. J. Biochem. 245324-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richard, M., R. R. Quijano, S. Bezzate, F. Bordon-Pallier, and C. Gaillardin. 2001. Tagging morphogenetic genes by insertional mutagenesis in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J. Bacteriol. 1833098-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rittmann, D., S. Schaffer, V. F. Wendisch, and H. Sahm. 2003. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Corynebacterium glutamicum: expression and deletion of the fbp gene and biochemical characterization of the enzyme. Arch. Microbiol. 180285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sato, T., H. Imanaka, N. Rashid, T. Fukui, H. Atomi, and T. Imanaka. 2004. Genetic evidence identifying the true gluconeogenic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in Thermococcus kodakaraensis and other hyperthermophiles. J. Bacteriol. 1865799-5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sedivy, J. M., and D. G. Fraenkel. 1985. Fructose bisphosphatase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cloning, disruption and regulation of the FBP1 structural gene. J. Mol. Biol. 186307-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sols, A. 1981. Multimodulation of enzyme activity. Curr. Top. Cell. Regul. 1977-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stec, B., H. Yang, K. A. Johnson, L. Chen, and M. F. Roberts. 2000. MJ0109 is an enzyme that is both an inositol monophosphatase and the “missing” archaeal fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 71046-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Traniello, S., M. Calcagno, and S. Pontremoli. 1971. Fructose 1,6-diphosphatase and sedoheptulose 1,7-diphosphatase from Candida utilis: purification and properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 146603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vassarotti, A., and J. D. Friesen. 1985. Isolation of the fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase gene of the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Evidence for transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2606348-6353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wurster, B., and B. Hess. 1976. Tautomeric and anomeric specificity of allosteric activation of yeast pyruvate kinase by D-fructose 1, 6-bisphosphate and its relevance in D-glucose catabolism. FEBS Lett. 6317-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yáñez, A. J., M. García-Rocha, R. Bertinat, C. Droppelmann, I. Concha, J. Guinovart, and J. C. Slebe. 2004. Subcellular localization of liver FBPase is modulated by metabolic conditions. FEBS Lett. 577154-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]