Abstract

Gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM) and gastric cancer are associated with Helicobacter pylori, but the bacterium often is undetectable in these lesions. To unravel this apparent paradox, IM, H. pylori presence, and the expression of H. pylori virulence genes were quantified concurrently using histologic testing, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry. H. pylori was detected inside metaplastic, dysplastic, and neoplastic epithelial cells, and cagA and babA2 expression was colocalized. Importantly, expression of cagA was significantly higher in patients with IM and adenocarcinoma than in control subjects. The preneoplastic “acidic” MUC2 mucin was detected only in the presence of H. pylori, and MUC2 expression was higher in patients with IM, dysplasia, and cancer. These novel findings are compatible with the hypothesis that all stages of gastric carcinogenesis are fostered by persistent intracellular expression of H. pylori virulence genes, especially cagA inside MUC2-producing precancerous gastric cells and pleomorphic cancer cells.

Helicobacter pylori is the main cause of distal gastric adenocarcinoma [1, 2]. The matched odds ratio (OR) for the association between H. pylori infection and subsequent development of noncardia gastric cancer is 3.0 [3], but the mechanism of this epidemiological association is unknown. The risk for developing cancer is greater in subjects infected by virulent strains carrying the cagA gene, the cag pathogenicity island (PAI) [4-6], and/or the blood group antigen-binding adhesin (babA2) gene that mediates the attachment of the microbe to the outside membrane of gastric epithelial cells [7, 8].

Even before the discovery of the role of H. pylori in gastric carcinogenesis, interpopulation comparisons demonstrated that increased prevalence of precursor lesions was associated with increased incidence of cancer [9]. The main precursor lesion is intestinal metaplasia (IM), which is defined as focal transformation of normal gastric epithelial cells into absorptive intestinal epithelial cells and goblet cells and the switch from the expression of gastric-type MUC5AC to intestinal-type MUC2 apomucin. It is now established that H. pylori plays a major role in this preneoplastic transformation [10], but the mechanism of H. pylori involvement is unknown. The interpretation of epidemiological observations is complicated by the fact that many of the precancerous and cancerous biopsy specimens are culture negative for H. pylori and that standard histologic test stains often do not demonstrate the presence of the bacterium in the lumen of glands of patients with IM or in cancerous tissues [11, 12]. In addition, the OR for distal gastric cancer increases from 2.1 to 9.6 if tests are made on serum samples obtained 10−15 years before the gastric cancer diagnosis was made, instead of samples obtained within 5 years of the time of diagnosis [3]. These findings have been interpreted as demonstrating that, although gastric carcinogenesis induced by H. pylori continues to progress, the microbe often disappears from the stomach before cancer is established [13].

To study this apparent paradox, we determined the presence of IM and of H. pylori in gastric biopsy specimens from patients with precancerous lesions and adenocarcinoma using light microscopy, laser confocal microscopy, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In addition, we used in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) to quantify mRNA and protein expression of bacterial virulence genes and of mucus genes associated with carcinogenesis. Using these highly specific and sensitive methods concurrently, we observed that H. pylori expressing both cagA and babA2 were present within precancerous and cancerous epithelial cells, that the relative expression of cagA per bacterium was significantly higher in patients with IM and adenocarcinoma, and that MUC2 was expressed only if H. pylori was present. These observations demonstrate that H. pylori can colonize MUC2-producing gastric cells and pleomorphic cancer cells and that the intracellular persistence of the bacteria may play a role throughout the stages of gastric carcinogenesis.

PATIENTS, MATERIALS, AND METHODS

Patients

H. pylori–positive patients previously diagnosed with IM by gastroscopy (n = 43; mean age [±SEM], 72 ± 1 years) underwent endoscopy again, and 2 antral gastric biopsy specimens were harvested. Control samples consisted of archival biopsy specimens harvested from 8 younger H. pylori–positive (age, 57 ± 2 years) patients with no known gastric disease and no prior record of IM (group V).

Biopsy specimens

Biopsy specimens were immediately fixed in Z-fix (10% paraformaldehyde plus 1% ionized Zn; Anatech), dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Serial 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin or Genta stain [14] for grading of gastritis and atrophy according to the Sydney system [15] (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, marked). In biopsy specimens with high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, no grading was made. Additional serial sections were prepared for ISH or IHC, as described below. For detection of mucin expression, sections 1 and 3 were processed by IHC for MUC5AC and MUC2, respectively, whereas section 2 was processed for MUC5AC and MUC2 expression using dual fluorescence ISH (FISH).

Oligonucleotide probes for H. pylori and mucins

The oligonucleotide probes are shown in table 1. Specific RNA and cDNA probes were designed using a sequence database (Gen-Bank) or, in the case of cagA, babA2, and MUC2, probes were selected as described elsewhere [8, 16, 17]. All probes were synthesized in the Synthesis and Sequencing Facility, Biomedical Instrumentation Center, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS; Bethesda, Maryland). The 5′ end of the oligonucleotides was labeled with either biotin or digoxigenin-3−0-methylcarbonyl-ε-aminocaproic acid-N-hydroxy-succinimide ester (DIG-NHS ester; Roche Diagnostics). In initial experiments, we used both RNA and cDNA probes concurrently and confirmed earlier observations that the 2 probes can detect the same structures. In addition, we observed that detection was abolished by RNase but not by DNase (see “Controls” subsection below), further demonstrating that these probes were specifically targeting mRNA. Having validated the cDNA antisense probes in our system, we subsequently included RNase and DNase controls with each run and discontinued the use of RNA probes, because they are more susceptible to degradation and more delicate and costly to prepare.

Table 1.

Sequences for Helicobacter pylori and apomucin DNA probes (RNA probes were identical except for substitution of U for T).

| Probe, DNA, primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| H. pylori | |

| 16S rRNA | |

| Antisense | 5′-TACCTC TCC CACACTCTAGAATAGTAGTTTCAAATGC-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-CTA TGA CGG GTA TCC GGC-3′ |

| cagA [16] | |

| Antisense | 5′-CTG CAA AAG ATT GTT TGG CAG A-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-GAT AAC AGG CAA GCT TTT GAG G-3′ |

| babA2 [8] | |

| Antisense | 5′-AAT CCA AAA AGG AGA AAA AGT ATG AAA-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-TGT TAG TGA TTT CGG TGT AGG ACA-3′ |

| Apomucins | |

| MUC5AC | |

| Antisense | 5′-AGT TGT GCT CGT TGT GGG AGC AGA GGT TGT GC-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-CGG GGA CAA GGA AAC CTA-3′ |

| MUC2 [17] | |

| Antisense | 5-TCC AAT GGG AAC ATC ACG ATA CAT GGT GGC-3′ |

| Sense | 5′-CCA TTC TCA ACG ACA ACC CCT ACT ACC CC-3′ |

In situ hybridization

All procedures for paraffin-embedded tissues were performed as described elsewhere [18] and at room temperature, except as specified.

For pretreatment, sections were first deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated by a series of washes in graded ethanol (95% [twice], 80%, 70%, and 50%), and washed in diethopyrocarbonate (DEPC)–treated water and PBS. To improve subsequent probe penetration, sections were treated with proteinase K (10 μg/mL in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 8.0] containing 5 mM EDTA; Roche Diagnostics) for 10 min and then were washed twice for 5 min each with 1× standard saline citrate (SSC; Quality Biological).

For prehybridization, sections were covered for 5 min with hybridization mixture prepared as follows: 200 μL of Denhardt's solution (2% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 2% ficoll, and 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone in water), 5 mL of formamide (Roche Diagnostic), 600 μL of 5 M NaCl, 2 mL of dextran sulfate (0.8 g/8mL) heated at 65°C for 20 min, 20 μL of EDTA (0.29 g/10 mL), 2.5 mL of hybridization solution (phenol-chloroform–extracted salmon testis DNA and SSC), 20 μL of 1.0 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), and 660 μL of DEPC-treated water. Sections were then covered for 20 min with blocking solution (0.2 g of BSA fraction V and 0.5 mL of normal horse serum; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 10 mL of immuno-Tris buffer (50 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.5] and 25 mL of 5 M NaCl in 1000 mL of water [pH 7.5]).

For hybridization, the probes listed in table 1 were denatured by heating for 10 min at 65°C and subsequent chilling on ice for 3 min. Each unstained section was layered with 70−100 μL of the probe solution (4 pmol/μL), coverslipped, and placed horizontally on filter paper soaked with water in an air-tight box wrapped with aluminum foil. Separate boxes were used for different probes and for negative controls. Each box was incubated overnight at 37°C.

For posthybridization, after 18 h of incubation, unbound probe was removed by successive washes in decreasing concentrations of SSC (2× SSC for 30 min, 1× SSC for 10 min, 0.5× SSC for 10 min, and 0.1× SSC for 15 min at 60°C).

For conventional light ISH, anti–digoxigenin antibody–conjugated or streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Roche Diagnostic) was used to detect the digoxigenin-labeled (cagA) or the biotin-labeled (babA2) probe, respectively (table 1). Sections were incubated for 2 h with 1:500 dilution of blocking immuno-Tris buffer. Unbound alkaline phosphatase was washed gently with immuno-Tris buffer (3 times for 5 min each), using a different Coplin jar for each probe and negative controls. Bound alkaline phosphatase was detected by covering the slides with a chromogenic substrate (nitro-blue-tetrazolium [NBT]; NBT/BCIP kit, Vector Laboratories) and by keeping them in the dark for 20 min. After washing in water for 3 min, slides were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Vector) for 15 min, washed in water, dehydrated, cleared in xylene, air dried, and mounted with permount.

Dual FISH localization was done as described elsewhere [19]. The hybridization mixture contained both a biotin-labeled probe recognizing H. pylori 16S rRNA and a digoxigenin-labeled probe recognizing cagA (table 1). After incubation as described above, the slides were covered with 3 layers. The first layer included 1 μL of avidin–Texas red plus 1.5 μL mouse monoclonal antidigoxigenin; the second layer included 10 μL of biotin–antiavidin plus 1 μL of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated rabbit anti–mouse IgG; and the third layer included 1 μL of avidin–Texas red plus 10 μL of monoclonal FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit. All antibodies were prepared in 1 mL of blocking solution. After each antibody layer was added, slides were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in a humid chamber and washed 3 times for 5 min each. After air-drying, the sections were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

The method described above for fluorescence microscopy dual localization of H. pylori was used for detection of apomucin gene expression in serial section 2. MUC2 and MUC5AC expression was detected using specific probes (table 1) and FITC and Texas red labels, respectively.

H. pylori pure cultures were streaked onto precleaned microscope slides and used as positive controls. Escherichia coli and Shigella flexneri cultures and gastric biopsy specimens from a 62-year-old H. pylori–negative patient with dyspepsia were used as negative controls. Control for nonspecific binding was performed by using sense instead of antisense probe, hybridization buffer instead of antisense probe, unlabeled antisense probe, digoxigenin- or biotin-labeled probe for the scorpion Buthus martensi Karsch neurotoxin sequence (5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT AC-3′) [20], RNase A pretreatment (Roche), DNase I pretreatment (Roche), and RNase plus DNase I pretreatment.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti–H. pylori antibody (dilution, 1:50; Biomeda), anti–H. pylori CagA antigen IgG fraction monoclonal antibody (dilution, 1:100; Austral Biologicals), and anti-MUC2 (LUM2−3) or anti-MUC5AC (LUM5−1) polyclonal antibodies (dilution, 1:1000) raised using keyhole limpet hemocyanin-conjugated peptides with the sequences NGLQPVRVEDPDGC and RNQDQQGPFKMC, respectively [21, 22]. Detection of bound primary antibody was performed using the StreptABComplex/HRP Duet kit (Dako), followed by incubation with 3,3′ diaminobenzidine (0.6 mg/mL) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.03% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min. Sections were counterstained with Harris's (for H. pylori and cagA detection) or Meyer's (for apomucin detection) hematoxylin.

Histochemistry

Alcian blue staining [14] was used to detect the presence of Alcian blue–positive mucins in the gastric mucosa, using sections adjacent to those used for ISH (i.e., section 4). Additional serial sections were stained with the high-iron diamine/Alcian blue/Steiner method [23], to concurrently detect H. pylori and to examine the type of intracellular mucin (sulfomucin or sialomucin).

Data analysis

An Eclipse Nikon microscope was used to examine the sections at 100×, 400×, and 1000× magnification. The number of silver-stained bacterial clusters and the mRNA expression was quantified at 400× magnification, according to a modification of the point-counting stereological method and using an intraocular reticle of 27-mm diameter, covering 3578 μm2 (i.e., 17,892 μm3 for 5-μm–thick sections; Kr409, Klarman Rulings) [24]. Two different morphometric analysis were performed: (1) number of H. pylori clusters identified as black structures after Genta stain, as cagA and babA2 blue structures after NBT-detecting alkaline phosphatase–ISH, or as 16S rRNA and cagA fluorescent structures during dual FISH (cells per 10,000 μm3); and (2) volumetric density of apomucin (Vvi per 10,000 μm3). Counts of clusters were made in 3 randomly selected entire fields-of-view. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was determined using analysis of variance. For reproduction purpose, images were digitized using a charge coupled device color camera (model HV-C20C20M; Hitachi) interfaced with a Sun X-20 workstation.

FISH laser confocal microscopy

The cellular localization of H. pylori was examined in selected 5-μm FISH preparations at 1000× magnification, using an MRC600 laser scanning confocal microscope (interfaced with a Zeiss Axiovert 35 Inverted microscope; Bioinstrumentation Center, USUHS). Series of ten 0.3-mm scans were obtained, and 3-dimensional images were constructed.

TEM

TEM was done as described elsewhere [25, 26]. Selected gastric biopsy specimens were fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3; 4°C), post-fixed in 1% phosphate-buffered osmium tetroxide (pH 7.3) for 60 min at 4°C, dehydrated in a series of increasing ethanol concentrations, embedded using flat molds in Spurr low-viscosity epoxy resin (Polysciences), and polymerized at 60°C for 18 h. Semithin sections (0.5 μm) stained with toluidine blue were used to identify areas of the gastric biopsy specimen with recognizable H. pylori–positive metaplastic cells (goblet cells and absorptive cells). Ultrathin sections (500 Å) of these areas were cut in an MT 6000 Sorvall ultramicrotome, mounted on 400 mesh cooper hexagonal grids (diameter, 3.05 mm), and stained with saturated aqueous solution of uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The grids were examined using a 100 CX JEOL or a CM 100 Phillips electron microscope at 80 kv (Bioinstrumentation Center, USUHS).

RESULTS

On the basis of histological criteria [15], biopsy specimens from patients with prior diagnosis of antral IM were classified as “IM absent” (group I: n = 23; age, 72 ± 1 years), “IM present” (group II: n = 12; age, 72 ± 3 years); “dysplasia” (group III: n = 3; age, 77 ± 7 years), and “differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinoma” (group IV: n = 5; age, 80 ± 1.5 years). It is important to note that the criterion used to select patients in groups I–IV was the presence of IM at a previous endoscopy and that the absence of IM in biopsy specimens used for the present study is due to the fact that it is a focal lesion that can be missed in nontargeted endoscopic biopsy specimens. Furthermore, spontaneous regression of IM has not been reported and has been observed only in long-term studies after eradication of H. pylori associated with administration of micro-nutrients [27]. Archival biopsy specimens harvested from 8 H. pylori–positive patients with no known gastric disease and no prior record of IM served as controls (group V: age, 57 ± 2 years).

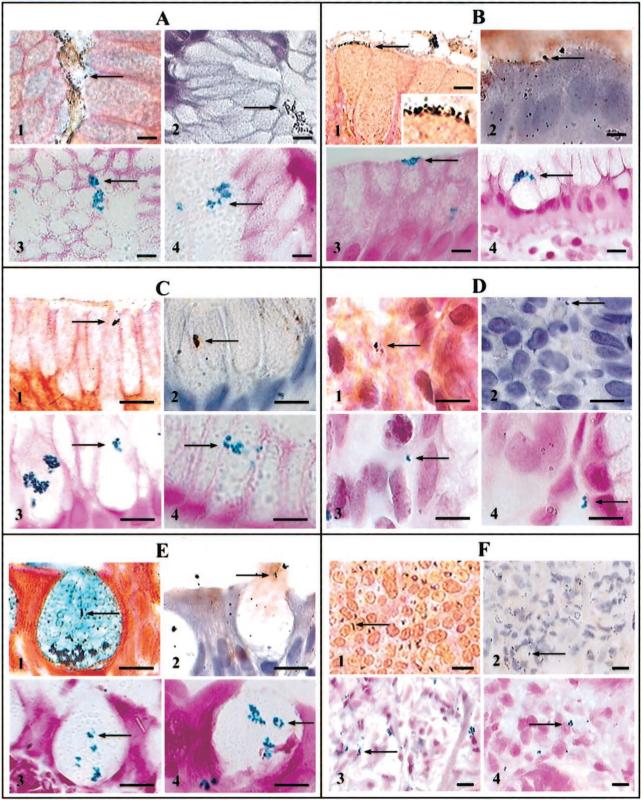

H. pylori were present in all biopsy specimens by Genta stain and IHC. In groups I and V, H. pylori were observed in the lumen of antral gastric glands (figure 1A, pictures 1 and 2), close to the luminal surface of columnar epithelial cells (figure 1B and figure 2B), within gastric epithelial cells (figure 1C, pictures 1 and 2), and in the areolar connective tissue (figure 1D, pictures 1 and 2). H. pylori were seldom observed free-floating in the lumen of gastric gland specimens from patients with IM, but they occasionally were detected attached to, or within the cytoplasm of, goblet cells in specimens from group II (figure 1E, pictures 1 and 2), in dysplastic cells in specimens from group III (not shown), and in pleomorphic cells of gastric adenocarcinoma specimens from group IV (figure 1F, pictures 1 and 2). cagA and babA2 genes were expressed in the lumen of glands and inside epithelial cells of H. pylori–positive (but not H. pylori–negative) biopsy specimens (figure 1A–E, pictures 3 and 4), and expression was absent in RNase-treated, but not DNase-treated, sections. The CagA product was detected by IHC in the same locations. All positive controls were positive, and all negative controls were negative for both cagA and babA2 expression. Dual FISH demonstrated that, within the same biopsy specimen, some 16S rRNA–positive H. pylori expressed cagA (figure 2A, pictures 1 and 2), whereas others did not (figure 2A, pictures 3 and 4). The same was true for babA2 expression.

Figure 1.

Luminal, intracellular, and interstitial colonization of the gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori in 4 groups of patients (bars, 10 μm). Bacteria are visualized in the lumen of antral gastric glands (A), in close proximity to the luminal surface of columnar epithelial cells (B; insert, details of H. pylori), within mucus-secreting cells (C), in the areolar connective tissue (D), within goblet cells (E), and in pleomorphic cells of gastric adenocarcinoma (F). Within each group of 4 pictures, picture 1 depicts Genta stain, picture 2 depicts anti–H. pylori immunohistochemistry, picture 3 depicts cagA expression by in situ hybridization (ISH), and picture 4 depicts babA2 expression by ISH.

Figure 2.

A, (pictures 1 and 3), Dual-fluorescent localization of 16S rRNA–positive Helicobacter pylori (red). In picture 2, the 16S rRNA–positive bacterial cluster expresses cagA (green), whereas in picture 4, there is no colocalization of 16S rRNA and cagA (bars, 10 μm). B, H. pylori and mucin detection using high-iron diamine/Alcian blue/Steiner stain (bars, 10 μm) [23]. High-iron diamine stains sulfomucin black, Alcian blue stains sialomucin blue, and silver stains H. pylori. Picture 1, adhesion of 1 H. pylori to the apical membrane of a goblet cell in an area containing sulfomucin; picture 2, 4 H. pylori sectioned under different angles and surrounded by a clear halo within grey-stained sulfomucin; picture 3, H. pylori surrounded by an area stained blue only (no sulfomucin) inside a goblet cell in the process of discharging mucus into the gastric lumen (note that the halo surrounding H. pylori stains blue); and picture 4, 1 H. pylori sectioned transversely and surrounded by a clear halo within gray-stained sulfomucin. C, Apomucin expression in 3 serial sections of normal and precancerous mucosa by dual fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH; pictures 1−4) and immunoperoxidase immunohistochemistry (IHC; pictures 5−8; bars, 10 μm). In normal epithelial cells (pictures 1 and 2 and pictures 5 and 6), MUC5AC is expressed (pictures 1 and 5; arrows) but MUC2 is not (pictures 2 and 6). In goblet cells (pictures 3 and 4 and pictures 7 and 8), MUC5AC is not expressed (pictures 3 and 7) but MUC2 is expressed (pictures 4 and 8; arrows). D, MUC5AC and MUC2 expression in 3 serial sections of adenocarcinoma matrix by dual FISH (pictures 1 and 2) and immunoperoxidase IHC (pictures 3 and 4; bars, 10 μm). Pictures 1 and 2 (serial section 2): dual-fluorescent reaction for MUC5AC (picture 1, negative) and MUC2 (picture 2, positive; arrow) expression by FISH; picture 3 (serial section 1): anti–MUC5AC IHC (negative); and picture 4 (serial section 3): anti-MUC2 IHC (positive; arrow).

Quantification of Genta stains and conventional light ISH (table 2) demonstrated that H. pylori density and the expression of cagA and babA2 were significantly greater in biopsy specimens from patients with a history of IM, compared with control subjects, even if no IM was present in the biopsy specimen examined (groups I and II vs. group V). In addition, expression of cagA, but not babA2, was significantly higher in biopsy specimens from patients with IM (group II vs. group I; P < .05). In patients with high-grade dysplasia (group III), H. pylori density was significantly greater than in patients in groups I and II, and cagA expression was lower than babA2 expression (P < .05). In patients with adenocarcinoma (group IV), H. pylori density was also greater, but cagA expression was significantly higher than babA2 expression (P < .05). In addition, cagA was expressed inside a significantly greater fraction of cells than babA2 (group II, goblet cells: 30% ± 5% vs. 19% ± 2%; group III, dysplastic cells: 36% ± 7% vs. 16% ± 1%; and group IV, pleomorphic cells: 37% ± 4% vs. 15% ± 1%; P < .05).

Table 2.

Cell counts of Helicobacter pylori clusters and determination of volumetric density (Vvi) of apomucin mRNA expression per field of view (at 400× magnification) in gastric biopsy specimens.

|

H. pylori cells/10,000 μm3 |

H. pylori fluorescence, cells/10,000 μm3 |

cagA:16S rRNA ratio, fluorescence | Apomucin volumetric density, Vvi/10,000 μm3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Genta stain | cagA | babA2 | 16S rRNA | cagA | MUC5AC | MUC2 | |

| I (n = 23) | 47.9 ± 3.6a | 27.3 ± 3.7a | 26.6 ± 2.6a | 32.6 ± 3.3a | 19.4 ± 2.0a | 0.60 ± 0.06a | 148 ± 19a | 80 ± 9 |

| II (n = 12) | 46.1 ± 1.7a | 39.8 ± 2.5a | 27.3 ± 5.7a | 41.3 ± 3.1a | 31.9 ± 3.1a | 0.76 ± 0.03a | 155 ± 8a | 260 ± 12a |

| III (n = 3) | 60.9 ± 3.2a | 21.1 ± 1.1a | 31.6 ± 0.6a | 44.3 ± 10.9a | 20.6 ± 4.9a | 0.50 ± 0.10 | 46 ± 7a | 116 ± 2a |

| IV (n = 5) | 69.7 ± 9.5a | 55.2 ± 11.9a | 15.0 ± 3.8a | 67.0 ± 10.2a | 55.2 ± 10.3a | 0.81 ± 0.04a | 109 ± 42a | 336 ± 55a |

| V (n = 8) | 12.3 ± 1.5 | 4.5 ± 2.5 | 4.6 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 1.8 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 481 ± 14 | 60 ± 41 |

NOTE. Data are mean ± SEM. Group I, patients with no evidence of intestinal metaplasia (IM) in gastric biopsy specimens; group II, patients with evidence of IM in gastric biopsy specimens; group III, patients with evidence of dysplasia in gastric biopsy specimens; group IV, patients with gastric adenocarcinoma; and group V, patients with no history of IM (control subjects). In the absence of H. pylori infection, all values were 0, except for MUC5AC expression, which was 296 Vvi/10,000 μm3. cagA and babA2, virulence mRNA expression; Genta stain, silver-stained bacteria.

P<.05, vs. group V.

Similar differences were observed using dual FISH (table 2), but 16S rRNA density was generally lower than H. pylori density by using Genta stain. This difference could reflect the lack of specificity of silver staining. However, individual values obtained by the 2 methods were highly correlated (P < .001), suggesting that only a fraction of silver-stained H. pylori express 16S rRNA or that fluorescence faded during the counting of fluorescent clusters. The latter interpretation is supported by the observation that cagA expression was consistently lower when determined by FISH, compared with bright-field ISH, and that the 2 were significantly correlated (P < .0001). In addition, the ratio of cagA to 16S rRNA was significantly higher in groups II and IV than in group I (table 2; P < .05). Of interest, inflammation scores tended to be higher in group II than in group I (1.8 ± 0.4 vs. 1.0 ± 0.2; P, not significant), and was significantly higher than that in control subjects (group V, 0.4 ± 0.3; P < .05). Atrophy scores did not differ among groups.

To further investigate the interactions between H. pylori and goblet cells, we used the high-iron diamine/Alcian blue/Steiner stain to examine whether the type of intracellular mucin (sulfomucin or sialomucin) influenced the presence of H. pylori within those cells. H. pylori did not attach to the surface of goblet cells, except when those cells contained sulfomucins (figure 2B, picture 1), as reported elsewhere [23]. In addition, H. pylori present inside goblet cells were surrounded by either Alcian blue–positive sialomucin granules (figure 2B, picture 2) or high-iron diamine–stained sulfomucins (figure 2B, pictures 3 and 4). ISH and IHC performed in subsequent serial sections confirmed that H. pylori was present in those cells.

We then explored the associations among H. pylori infection, cagA expression, and IM at the cellular and molecular level. MUC5AC was expressed in normal epithelial cells (figure 2C, pictures 1 and 5), whereas MUC2 expression was very low or absent (figure 2C, pictures 2 and 6). The opposite was observed in goblet cells (figure 2C, pictures 3 and 7 vs. pictures 4 and 8). In gastric adenocarcinoma, MUC5AC expression was low (figure 2D, pictures 1 and 3), whereas MUC2 mRNA and MUC2 apomucin were detected (along with cagA-positive H. pylori, as described above) in the connective tissue and in the extracellular matrix (figure 2D, pictures 2 and 4). By morphometric analysis, MUC5AC expression was similar in patients with no history of gastric disease, whether they were H. pylori–positive or not (table 2), and was significantly decreased in all patients with prior history of IM (table 2, groups I–IV). MUC2 expression was low in the absence of IM (groups I and V), and was significantly higher in biopsy specimens from patients with IM, dysplasia, or cancer, compared with biopsy specimens from patients without IM (table 2). In addition, MUC2 and cagA expression were significantly correlated in biopsy specimens from patients with IM (r = 0.897; P < .05), but not in specimens from patients without IM (r = 0.315).

Confocal microscopy demonstrated that H. pylori–specific 16S rRNA was expressed within the cytoplasm of normal (data not shown) and metaplastic (figure 3) gastric mucosal cells. TEM also demonstrated the presence of structures compatible with H. pylori in the cytoplasm of normal gastric mucosal cells (data not shown) and of metaplastic columnar absorptive cells (figure 4A). H. pylori were observed in the lumen of gastric glands and also in close approximation with surface microvilli of metaplastic epithelial absorptive cell (figure 4B). A low-electron-density circular spot was occasionally visible in one of the extremities of the bacteria (figure 4B), which suggests that there is accumulation of polyphosphate granule in vitro, as described elsewhere [28]. Structures suggestive of late-stage coccoidal forms of H. pylori were observed within the cytoplasm of goblet cells (figure 5). These structures were tightly packed between mucin droplets of different densities, typical of the “checkerboard appearance” reported elsewhere [29], and up to 3 flagellar filaments attached to 1 pole of H. pylori were visible between mucin granules (figure 5). The presence of flagellar filaments have been observed in coccoid forms of H. pylori [30].

Figure 3.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) laser confocal microscopic illustration of Helicobacter pylori intracellular localization. Right, pseudo–3-dimensional reconstruction of 10 serial 0.3-μm scans recorded by observing a FISH preparation of H. pylori–specific 16S rRNA at 1000× magnification (bar, 10 μm). Left, schematic representation of cell contours and of some of the most prominent intracellular clusters of H. pylori. A, absorptive columnar cell; G, goblet cell.

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of a metaplastic gland containing columnar absorptive cells with surface microvilli and associated terminal web. A, Cell containing intracytoplasmic Helicobacter pylori (arrows) that are not surrounded by specialized cellular interface (magnification, ×17,000). B, Detail of the surface of a cell illustrating the presence of an H. pylori in the gastric gland lumen that is close to the surface microvilli and to the associated terminal web. No specialized pedestal-like formation is seen. A low-electron-density circular spot is present in one of the extremities of the bacteria, suggesting the accumulation of polyphosphate granule (magnification, ×33,000; bar, 1 μm).

Figure 5.

Goblet cell mucus granules of different densities creating a “checkerboard” appearance [29]. Long arrow, structure that closely resembles a late-stage coccoidal form of Helicobacter pylori [30]. Arrowheads, 3 structures resembling flagellar filaments that appear to emerge from a single pole of the cell and are in close contact with the mucus granules (magnification, ×24,000; bar, 1 μm).

DISCUSSION

The present data demonstrate that H. pylori and cagA virulence gene expression can be detected in the cytoplasm of preneo-plastic goblet cells and pleomorphic cells of gastric adenocarcinoma by using concurrently standard light microscopy, ISH, IHC, confocal microscopy, and TEM. Of importance, the number of intracellular and interstitial H. pylori– and cagA-positive clusters are increased in patients with IM and cancer, compared with that in control subjects with gastritis (table 2); in contrast, as mentioned above, colonization of the lumen of gastric glands by H. pylori gradually decreases during progression of chronic gastritis to atrophic gastritis, IM, dysplasia, and gastric cancer. In addition, our data confirm not only that the bacterium can be present inside normal gastric epithelial cells and in the lamina propria [31-36] but also that they can attach to goblet cells [37, 38]. Despite the relevance and importance of H. pylori invasiveness, this bacterial property is rarely considered to play a role in pathogenicity, and its potential involvement in gastric carcinogenesis has not been evaluated. This may be explained by the fact that intracellular and interstitial bacteria are difficult to detect by light microscopy because of their small size (3−5 μm) and because H. pylori staining (e.g., silver stain and Giemsa) also may stain many of the host's cellular organelles (e.g., cell membranes).

To circumvent the lack of specificity of standard light microscopy for intracellular detection of H. pylori, we concurrently used a combination of ISH, IHC, confocal microscopy, and TEM. Although the use of each technique separately might produce false-positive results, their concurrent use in biopsy specimens obtained from patients with and without IM and adenocarcinoma showed excellent concordance between the results, thus further supporting their validity. ISH was used because it permits the localization and relative quantitation of mRNA expression in single cells or in a population of cells. This technique was used elsewhere to demonstrate colocalization of H. pylori–specific 16S rRNA and silver-stained bacteria in the gastric lumen of patients without precancerous lesions [39]. Here, we improved the sensitivity and specificity of H. pylori detection by combining IHC with ISH, by using specific probes for 3 different genes, and by systematically including negative controls. Using these techniques concurrently, we were able to detect increased expression of the cagA gene and its protein inside precancerous and cancerous cells, compared with that in normal epithelial cells (table 2). Although cagA expression has not been detected previously within gastric epithelial cells, coculture of H. pylori and AGS cells was associated with delivery of the 145-kDa CagA protein into gastric adenocarcinoma cell lines by the cag type IV secretion system [40, 41], with resulting intracellular tyrosine phosphorylation, induction of signal transduction pathways [41], activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) cascades, and expression of proto-oncogenes [42]. Our data indicate that intracellular H. pylori also express cagA and babA2 and are likely to produce in vivo the cellular metabolic transformation shown to occur in vitro [41]. Therefore, gastric neoplastic transformation may be induced and sustained, at least in part, by intracellular expression of cagA in vivo. This effect could play a role not only during the early stages of gastric carcinogenesis but also perhaps later during this process.

The proposed role of intracellular CagA in gastric carcinogenesis is supported by a recent study that showed that 20% of patients with noncardia gastric cancer are CagA seropositive, even though they are H. pylori seronegative, and that the OR for distal gastric cancer increases from 2.2 for subjects testing H. pylori–positive versus those testing H. pylori–negative to 27.7 for subjects testing CagA-positive versus those testing CagA-negative [43]. In the present study, dual FISH demonstrated that, within the very same biopsy specimen, some 16S rRNA–positive H. pylori expressed cagA (figure 2A, pictures 1 and 2), whereas others did not (figure 2A, pictures 3 and 4), which may reflect the recently reported in vivo occurrence of genetic divergence between subclones of H. pylori [44]. Our findings also are compatible with the occurrence of coinfection by both cagA-positive and cagA-negative H. pylori subclones or strains in patients with precancerous lesions, as was shown in most patients with nonulcer dyspepsia [45, 46].

By exploring the association between H. pylori infection, cagA expression, and IM at the cellular and molecular level, we confirmed that H. pylori attach to the surface of goblet cells only if sulfomucins are present (figure 2B, picture 1), as reported elsewhere [23, 38]. We also observed that the microbes were detected within sialomucin-producing, as well as within sulfomucin-producing, goblet cells (figure 2B, pictures 2−4). Thus, Alcian-blue–stained sialomucins appear to allow H. pylori entry into goblet cells, but not their adhesion to the cell surface. TEM showed the presence of structures compatible with H. pylori within the cytoplasm of normal (data not shown), of metaplastic columnar absorptive cells (figure 3A) and of goblet cell (figure 4). These ultrastructural observations confirm and extend the previous reports that H. pylori are present within normal gastric epithelial cells [32, 34, 47, 48]. In addition, taken in the context of our observations using light and confocal microscopy (figures 1, 2, and 3), they confirm that H. pylori can invade gastric metaplastic cells.

These in vivo observations are further supported by the recent demonstration that H. pylori can enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of gastric adenocarcinoma epithelial cells in vitro [49]. The entry process involves specific phagocytic mechanisms that are dependent on host cell determinants, as demonstrated by the observation that entry is more extensive in AGS cells (derived from gastric cancer cells) than in HeLa or HEp-2 cells (derived from nongastric cancer cells) [50]. Such differences could be ascribed to different expression of dynamin isoforms in the various cell types [51]. An intact f-actin cytoskeleton appears to be required for intracellular penetration in vitro [49], and a similar requirement is likely to occur in vivo. Entry of H. pylori into cultured gastric adenocarcinoma cells also depends on active processes of bacterial motility [52] and on other yetundefined bacterial factors. One of these factors could be the homologue of Yersinia, Rickettsia, and Salmonella species invA gene [53-55], which is also expressed in H. pylori [56].

The present study does not provide evidence that H. pylori actually divide within gastric goblet cells, but the fact that they express 16S rRNA, cagA, and babA2 indicate that they are alive. This possibility is further supported by the recent in vitro demonstration that the bacteria can survive for up to 48 h within cytoplasmic vacuoles of gastric adenocarcinoma cells, that they can move within the vacuoles with the help of flagellar activity, and that intravacuolar replication may occur [49]. Our observation that H. pylori can be released with mucus into the lumen of metaplastic glands (figure 1E, picture 2; figure 2B, picture 3) and sometimes adhere to goblet cells (figure 2B, picture 1) is compatible with the hypothesis that coccoid bacteria can restart growth and division, and then re-enter other metaplastic cells. This process would be similar to the bacterial movement recently observed in vitro [49]. At this time, the mechanism of passage of H. pylori into the lamina propria or directly between cells in infected patients remains unknown.

We also examined whether the intensity of intracellular and interstitial colonization and expression of virulence genes were related to the stage of gastric carcinogenesis. As shown in table 2, H. pylori colonization was greater in patients with a history of IM, compared with that in control subjects, even if precancerous lesions were not present in the biopsy specimen that was examined. Colonization was even greater in neoplastic cells. Expression of cagA, but not babA2, was higher in biopsy specimens from patients with IM, compared with biopsy specimens from patients without IM and with specimens from control subjects, and the absolute levels of cagA and babA2 expression were greater in specimens from patients with high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. In addition, the level of cagA, but not babA2, expression relative to the number of bacteria present in specimens from patients with adenocarcinoma was significantly higher than that in specimens from patients with dysplasia. The clinical relevance of these observations is unclear, but they suggest that gastric carcinogenesis is related to the bacterial load and/or to the intracellular expression of virulence genes and that high expression of cagA appears to be directly related to IM and intestinal-type adenocarcinoma, whereas other factors may be responsible for high-grade dysplasia. In addition, the observation that babA2 expression remained unchanged in the presence of an increase in H. pylori density may reflect a down-regulation of this adhesion molecule when more bacteria invade epithelial cells.

The observation that 6 of 41 patients had developed gastric dysplasia and/or gastric cancer since the endoscopy at which IM had been diagnosed is consistent with the precancerous nature of this lesion. The hallmark of gastric IM is the presence of MUC2, an apomucin normally present in the intestine, but not in the stomach [57]. Similar to aberrant mucin expression/structure reported in other pathological conditions, including neoplasia [58], expression of MUC2 gene was found to be increased in gastric regenerative, metaplastic, and neoplastic epithelia [17], and aberrant MUC2 apomucin synthesis by gastric cells is considered to be preneoplastic [59]. Of interest, coregulation of fucosyltransferase (FUT1, FUT2, or FUT3) determines the differential expression of MUC5AC and MUC6, which is lost in gastric cancer, leading to metaplastic production of MUC2 [60]. In addition, there is recent evidence that overexpression of MUC2 in colon cancer can be induced by NF-kB and requires the presence of Ras, Raf, and MEK signaling proteins [61]. These latter factors are persistently overexpressed during H. pylori infection [62]. Here, we observed that the MUC2 gene was expressed in goblet cells, as reported elsewhere [57], but also in normal epithelial cells of H. pylori–positive subjects, and that the levels of MUC2 and cagA expression were significantly correlated in biopsy specimens from patients with IM. In contrast, MUC5AC expression was decreased significantly if the patient had a history of IM, which was associated with greater H. pylori colonization and cagA expression (table 2). In addition, MUC2 expression was increased in the connective tissue and in the extracellular matrix of intestinal type gastric adenocarcinoma, as reported elsewhere [63], but there was no detectable MUC5AC expression (figure 2D). However, the present data do not prove that gastric cancer originates from goblet cells, and the malignant cells may have evolved from other cells. In addition, the number of patients with cancer is relatively low, although the present observations are in agreement with epidemiological data suggesting that the risk of gastric cancer may be increased in the presence of long term and/or heavy colonization by virulent H. pylori.

In conclusion, the present observations demonstrate that H. pylori is an invasive organism that expresses virulence factors within precancerous and cancerous cells. In addition, cagA expression within superficial and foveolar mucus-secreting cells is associated with aberrant expression of the MUC2 gene and Alcian blue–positive mucus production. Although a causal relationship between these 2 findings is not proven by these novel observations, they are compatible with a possible role for intracellular H. pylori in the carcinogenesis process. In addition, they are in agreement with the recent finding that H. pylori eradication can induce regression of cancer precursor lesions [27, 64-66] and may prevent relapse of early gastric carcinoma [2]. They also support the proposed hypothesis that H. pylori continues to play a role in the advanced stages of gastric carcinogenesis [23].

Acknowledgments

We thank Charlie Brown (National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland), for helpful discussions; Lillie Hemen-Ackah and Hiwot Woreta, for technical assistance; and Tom Baginski and József Czégé (Bioinstrumentation Center, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland), for assistance with confocal microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and image processing.

Financial support: Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine; Swedish Medical Research Council (grant 7902); Crafoord Foundation; Österlunds Stiftelse; Medical Faculty of Lund University.

Footnotes

Presented in part: Digestive Diseases Week, Atlanta, 23 May 2001 (Gastroenterology 2001; 120:3902A).

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Health Care System and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study entry.

References

- 1.Anonymous . IARC Monograph on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:639–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, et al. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I–specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Orentreich N, Vogelman H. Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;40:297–301. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilver D, Arnqvist A, Ogren J, et al. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science. 1998;279:373–7. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhard M, Lehn N, Neumayer N, et al. Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for blood-group antigen-binding adhesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12778–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haenszel W, Correa P. Developments in the epidemiology of stomach cancer over the past decade. Cancer Res. 1975;35:3452–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(Suppl 1):S37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craanen ME, Blok P, Dekker W, Ferwerda J, Tytgat GN. Subtypes of intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1992;33:597–600. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakaki N. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer in view of relation to atrophy of background gastric mucosa [in Japanese]. Nippon Rinsho. 1993;51:3242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda H, Saito D, Hayashi S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection, serum pepsinogen level, and gastric cancer: a case-control study in Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genta RM, Robason GO, Graham DY. Simultaneous visualization of Helicobacter pylori and gastric morphology: a new stain. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:221–6. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis: the updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tummuru MK, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Cloning and expression of a high-molecular-mass major antigen of Helicobacter pylori: evidence of linkage to cytotoxin production. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1799–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1799-1809.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitsuuchi M, Hinoda Y, Itoh F, et al. Expression of MUC2 gene in gastric regenerative, metaplastic and neoplastic epithelia. J Clin Lab Anal. 1999;13:259–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1999)13:6<259::AID-JCLA2>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson DG. In situ hybridization: a practical approach. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaju R, Haas OA, Neat M, et al. A new recurrent translocation, t(5;11)(q35;p15.5), associated with del(5q) in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. The UK Cancer Cytogenetics Group (UKCCG). Blood. 1999;94:773–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan Z-D, Dai L, Zhuo X-L, Feng J-C, Xu K, Chi CW. Gene cloning and sequencing of BmK AS and BmK AS-1, two novel neurotoxins from the scorpion Butus martensi Karsch. Toxicon. 1999;37:815–23. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrmann A, Davies JR, Lindell G, et al. Studies on the “insoluble” glycoprotein complex from human colon: identification of reduction-insensitive MUC2 oligomers and C-terminal cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15828–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hovenberg HW, Davies JR, Carlstedt I. Different mucins are produced by the surface epithelium and the submucosa in human trachea: identification of MUC5AC as a major mucin from the goblet cells. Biochem J. 1996;318:319–24. doi: 10.1042/bj3180319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bravo JC, Correa P. Sulphomucins favour adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to metaplastic gastric mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:137–40. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semino-Mora MC, Leon-Monzon M, Dalakas MC. The effect of l-carnitine on the AZT-induced destruction of human myotubes. I. l-carnitine prevents the myotoxicity of AZT in vitro. Lab Invest. 1994;71:102–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semino-Mora C, Dalakas MC. Rimmed vacuoles with beta-amyloid and ubiquitinated filamentous deposits in the muscles of patients with long-standing denervation (postpoliomyelitis muscular atrophy): similarities with inclusion body myositis. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1128–33. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalakas MC, Semino-Mora C, Leon-Monzon M. Mitochondrial alterations with mitochondrial DNA depletion in the nerves of AIDS patients with peripheral neuropathy induced by 2′3′-dideoxycytidine (ddC). Lab Invest. 2001;81:1537–44. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, et al. Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti–Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1881–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segal ED, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Helicobacter pylori attachment to gastric cells induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1259–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawson PA, Filipe MI. An ultrastructural and histochemical study of the mucous membrane adjacent to and remote from carcinoma of the colon. Cancer. 1976;37:2388–98. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2388::aid-cncr2820370531>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Worku ML, Sidebotham RL, Walker MM, Keshavarz T, Karim QN. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori motility, morphology and phase of growth: implications for gastric colonization and pathology. Microbiology. 1999;145:2803–11. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-10-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen LP, Holck S. Possible evidence of invasiveness of Helicobacter (Campylobacter) pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:135–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01963640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyle FA, Tarnawski A, Schulman D, Dabros W. Evidence for gastric mucosal cell invasion by C. pylori: an ultrastructural study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:S92–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199001001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans DG, Evans DJ, Graham DY. Adherence and internalization of Helicobacter pylori by HEp-2 cells. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1557–67. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91714-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubois A, Fiala N, Heman-Ackah LM, et al. Natural gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori in monkeys: a model for human infection with spiral bacteria. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1405–17. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engstrand L, Graham D, Scheynius A, Genta RM, El Zaatari F. Is the sanctuary where Helicobacter pylori avoids antibacterial treatment intracellular? Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:504–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/108.5.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ko GH, Kang SM, Kim YK, et al. Invasiveness of Helicobacter pylori into human gastric mucosa. Helicobacter. 1999;4:77–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.98690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genta RM. Helicobacter pylori as a promoter of intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer: an alluring hypothesis in search of evidence. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7(Suppl 1):S25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Genta RM, Gurer IE, Graham DY, et al. Adherence of Helicobacter pylori to areas of incomplete intestinal metaplasia in the gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1206–11. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karttunen TJ, Genta RM, Yoffe B, Hachem CY, Graham DY, El-Zaatari FA. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in paraffin-embedded gastric biopsy specimens by in situ hybridization. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:305–311. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/106.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stein M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1263–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer-ter-Vehn T, Covacci A, Kist M, Pahl HL. Helicobacter pylori activates mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades and induces expression of the proto-oncogenes c-fos and c-jun. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16064–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ekström AM, Held M, Hansson LE, Engstrand L, Nyrén O. The role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer revised: CagA immunoblot as a marker of past infection. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:784–91. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Björkholm B, Lundin A, Sillén A, et al. Comparison of genetic divergence and fitness between two subclones of H. pylori. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7832–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7832-7838.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fantry GT, Zheng QX, Darwin PE, Rosenstein AH, James SP. Mixed infection with cagA-positive and cagA-negative strains of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1996;1:98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.1996.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Figura N, Vindigni C, Covacci A, et al. cagA positive and negative Helicobacter pylori strains are simultaneously present in the stomach of most patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia: relevance to histological damage. Gut. 1998;42:772–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noach LA, Rolf TM, Tytgat GN. Electron microscopic study of association between Helicobacter pylori and gastric and duodenal mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:699–704. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.8.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.el Shoura SM. Helicobacter pylori. I. Ultrastructural sequences of adherence, attachment, and penetration into the gastric mucosa. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:323–33. doi: 10.3109/01913129509064237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amieva MR, Salama N, Tompkins LS, Falkow S. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2002;4:677–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwok T, Backert S, Schwarz H, Berger J, Meyer TF. Specific entry of Helicobacter pylori into cultured gastric epithelial cells via a zipper-like mechanism. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2108–20. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2108-2120.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boleti H, Benmerah A, Ojcius DM, Cerf-Bensussan N, Dautry-Varsat A. Chlamydia infection of epithelial cells expressing dynamin and Eps15 mutants: clathrin-independent entry into cells and dynamin-dependent productive growth. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1487–96. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.10.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Björkholm B, Zhukhovitsky V, Lofman C, et al. Helicobacter pylori entry into human gastric epithelial cells: a potential determinant of virulence, persistence, and treatment failures. Helicobacter. 2000;5:148–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Revell PA, Miller VL. A chromosomally encoded regulator is required for expression of the Yersinia enterocolitica inv gene and for virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:677–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steele-Mortimer O, Brumell JH, Knodler LA, Meresse S, Lopez A, Finlay BB. The invasion-associated type III secretion system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is necessary for intracellular proliferation and vacuole biogenesis in epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:43–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaywee J, Radulovic S, Higgins JA, Azad AF. Transcriptional analysis of Rickettsia prowazekii invasion gene homolog (invA) during host cell infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6346–54. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6346-6354.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–47. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reis CA, David L, Correa P, et al. Intestinal metaplasia of human stomach displays distinct patterns of mucin (MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6) expression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1003–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho SB, Shekels LL, Toribara NW, et al. Mucin gene expression in normal, preneoplastic, and neoplastic human gastric epithelium. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2681–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor KL, Mall AS, Barnard RA, Ho SB, Cruse JP. Immunohisto-chemical detection of gastric mucin in normal and disease states. Oncol Res. 1998;10:465–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lopez-Ferrer A, de Bolos C, Barranco C, et al. Role of fucosyltransferases in the association between apomucin and Lewis antigen expression in normal and malignant gastric epithelium. Gut. 2000;47:349–56. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee HW, Ahn DH, Crawley SC, et al. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate up-regulates the transcription of MUC2 intestinal mucin via Ras, ERK, and NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32624–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wessler S, Hocker M, Fischer W, et al. Helicobacter pylori activates the histidine decarboxylase promoter through a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway independent of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence factors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3629–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Endoh Y, Tamura G, Motoyama T, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H. Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma mimicking complete-type intestinal metaplasia in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:826–32. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sung JJ, Lin SR, Ching JY, et al. Atrophy and intestinal metaplasia one year after cure of H. pylori infection: a prospective, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:7–14. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubois A, Semino-Mora MC, Woreta H, Doi S, Carlstedt I. H. pylori infection decreases expression of normal (MUC5AC) and increases expression of precancerous (MUC2) apomucins in non human primates. Gut. 2001;49:A47. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohkusa T, Fujiki K, Takashimizu I, et al. Improvement in atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in patients in whom Helicobacter pylori was eradicated. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:380–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-5-200103060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]